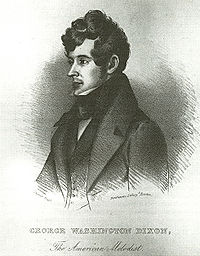

George Washington Dixon

Encyclopedia

Newspaper

A newspaper is a scheduled publication containing news of current events, informative articles, diverse features and advertising. It usually is printed on relatively inexpensive, low-grade paper such as newsprint. By 2007, there were 6580 daily newspapers in the world selling 395 million copies a...

editor

Editing

Editing is the process of selecting and preparing written, visual, audible, and film media used to convey information through the processes of correction, condensation, organization, and other modifications performed with an intention of producing a correct, consistent, accurate, and complete...

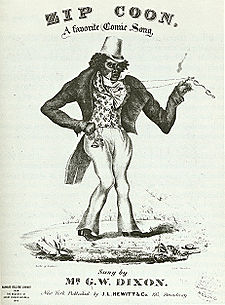

. He rose to prominence as a blackface

Blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used in minstrel shows, and later vaudeville, in which performers create a stereotyped caricature of a black person. The practice gained popularity during the 19th century and contributed to the proliferation of stereotypes such as the "happy-go-lucky darky...

performer (possibly the first American to do so) after performing "Coal Black Rose

Coal Black Rose

"Coal Black Rose" is a folk song, one of the earliest songs to be sung by a man in blackface. The song was first performed in the United States in the late 1820s, possibly by George Washington Dixon. It was certainly Dixon who popularized the song when he put on three blackface performances at the...

", "Zip Coon", and similar songs. He later turned to a career in journalism

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

, during which he earned the enmity of members of the upper class for his frequent allegations against them.

At age 15, Dixon joined the circus

Circus

A circus is commonly a travelling company of performers that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, unicyclists and other stunt-oriented artists...

, where he quickly established himself as a singer. In 1829, he began performing "Coal Black Rose" in blackface; this and similar songs would propel him to stardom. In contrast to his contemporary Thomas D. Rice

Thomas D. Rice

Thomas Dartmouth Rice was a white performer and playwright who used African American vernacular speech, song, and dance to become one of the most popular minstrel show entertainers of his time.-Background:...

, Dixon was primarily a singer rather than a dancer. He was by all accounts a gifted vocalist, and much of his material was quite challenging. "Zip Coon" became his trademark song.

By 1835, Dixon considered journalism to be his primary vocation. His first major paper was Dixon's Daily Review, which he published from Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA. According to the 2010 census, the city's population was 106,519. It is the fourth largest city in the state. Lowell and Cambridge are the county seats of Middlesex County...

, in 1835. He followed this in 1836 with Dixon's Saturday Night Express, published in Boston. By this point, he had taken to using his paper to expose what he considered the misdeeds of the upper classes. These stories earned him many enemies, and Dixon was taken to court on several occasions. His most successful paper was the Polyanthos, which he began publishing in 1838 from New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. Under its masthead, he challenged some of his greatest adversaries, including Thomas S. Hamblin

Thomas S. Hamblin

Thomas Sowerby Hamblin was an English actor and theatre manager. He first took the stage in England, then immigrated to the United States in 1825. He received critical acclaim there, and eventually entered theatre management. During his tenure at New York City's Bowery Theatre he helped establish...

, Reverend Francis L. Hawks

Francis L. Hawks

Dr. Francis Lister Hawks was an American priest of the Episcopal Church, and a politician in North Carolina....

, and Madame Restell

Madame Restell

Ann Trow , better known as Madame Restell, was an early-19th-century abortionist who practiced in New York City.-Biography:...

. After a brief foray into hypnotism, "pedestrianism" (long-distance walking), and other pursuits, he retired to New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The New Orleans metropolitan area has a population of 1,235,650 as of 2009, the 46th largest in the USA. The New Orleans – Metairie – Bogalusa combined statistical area has a population...

.

Dixon in blackface

Details about Dixon's childhood are scarce. The record suggests that he was born in Richmond, VirginiaRichmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

, probably in 1801. His parents were working-class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

folk, perhaps a barber and a washerwoman. He may have been educated at a charity school. Fairly detailed descriptions and portraits of Dixon survive; he had a swarthy complexion and a "splendid head of hair". However, the question of whether he was white or black is an open one. His enemies sometimes called him a "mulatto

Mulatto

Mulatto denotes a person with one white parent and one black parent, or more broadly, a person of mixed black and white ancestry. Contemporary usage of the term varies greatly, and the broader sense of the term makes its application rather subjective, as not all people of mixed white and black...

", a "Negro

Negro

The word Negro is used in the English-speaking world to refer to a person of black ancestry or appearance, whether of African descent or not...

", or referred to him as "Zip Coon", the name of the black character in one of his songs. However, the weight of evidence suggests that if Dixon did have black ancestry, it was fairly remote.

A newspaper story from 1841 claims that at age 15, Dixon's singing caught the attention of a circus proprietor named West. The man convinced Dixon to join his traveling circus as a stablehand and errand boy. Dixon traveled with this and other circuses for a time, and he appears as a singer and reciter of poems on bills dated from as early as February 1824. By early 1829, he had taken on the epithet "The American Buffo

Opera buffa

Opera buffa is a genre of opera. It was first used as an informal description of Italian comic operas variously classified by their authors as ‘commedia in musica’, ‘commedia per musica’, ‘dramma bernesco’, ‘dramma comico’, ‘divertimento giocoso' etc...

Singer".

Over three days in late July 1829, Dixon performed "Coal Black Rose

Coal Black Rose

"Coal Black Rose" is a folk song, one of the earliest songs to be sung by a man in blackface. The song was first performed in the United States in the late 1820s, possibly by George Washington Dixon. It was certainly Dixon who popularized the song when he put on three blackface performances at the...

" in blackface

Blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used in minstrel shows, and later vaudeville, in which performers create a stereotyped caricature of a black person. The practice gained popularity during the 19th century and contributed to the proliferation of stereotypes such as the "happy-go-lucky darky...

at the Bowery

Bowery Theatre

The Bowery Theatre was a playhouse in the Bowery neighborhood of New York City. Although it was founded by rich families to compete with the upscale Park Theatre, the Bowery saw its most successful period under the populist, pro-American management of Thomas Hamblin in the 1830s and 1840s...

, Chatham Garden

Chatham Garden Theatre

The Chatham Garden Theatre or Chatham Theatre was a playhouse in the Chatham Gardens of New York City. It was located on the north side of Chatham Street on Park Row between Pearl and Duane streets in lower Manhattan. The grounds ran through to Augustus Street...

, and Park

Park Theatre (Manhattan)

The Park Theatre, originally known as the New Theatre, was a playhouse in New York City, located at 21, 23, and 25 Park Row, about east of Ann Street and backing Theatre Alley. The location, at the north end of the city, overlooked the park that would soon house City Hall...

theatres in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. The Flash characterized his audience as "crowded galleries and scantily filled boxes"; that is, mostly working-class. On September 24 at the Bowery, Dixon performed Love in a Cloud, a dramatic interpretation of the events described in "Coal Black Rose" and possibly the first blackface farce

Farce

In theatre, a farce is a comedy which aims at entertaining the audience by means of unlikely, extravagant, and improbable situations, disguise and mistaken identity, verbal humour of varying degrees of sophistication, which may include word play, and a fast-paced plot whose speed usually increases,...

. These performances proved a hit, and Dixon rose to celebrity

Celebrity

A celebrity, also referred to as a celeb in popular culture, is a person who has a prominent profile and commands a great degree of public fascination and influence in day-to-day media...

, perhaps before any other American blackface performer had done so. On December 14, Dixon's benefit at the Albany Theatre grossed $155.87, the largest take there since the opening night earlier that year.

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution or in French, saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would in turn be overthrown...

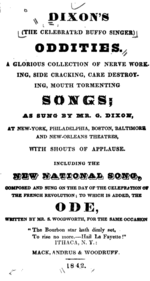

in France. He began selling a collection of songs and skits he had popularized called Dixon's Oddities in 1830; the book remained in print long after. Dixon mostly played to a working-class audience, including in his repertoire such songs as "The New York Fireman", which compared firefighters to the American Founding Fathers. Oratory

Oratory

Oratory is a type of public speaking.Oratory may also refer to:* Oratory , a power metal band* Oratory , a place of worship* a religious order such as** Oratory of Saint Philip Neri ** Oratory of Jesus...

made up another facet of his act; on December 4, 1832, the Baltimore Patriot reported that Dixon would read an address from the President at the Front Street Theatre.

In 1833, he started a small newspaper called the Stonington

Stonington, Connecticut

The Town of Stonington is located in New London County, Connecticut, in the state's southeastern corner. It includes the borough of Stonington, the villages of Pawcatuck, Lords Point, Wequetequock, the eastern halves of the villages of Mystic and Old Mystic...

Cannon. However, the publication saw little success, and by January 1834, he was performing again, now with new talents, such as ventriloquism

Ventriloquism

Ventriloquism, or ventriloquy, is an act of stagecraft in which a person manipulates his or her voice so that it appears that the voice is coming from elsewhere, usually a puppeteered "dummy"...

. Dixon seemed untarnished by his yearlong hiatus. Reviews said that "his voice seems formed of the music itself— 'it thrills, it animates' . . . ." The Telegraph wrote,

Few Melodists have gained more celebrity or been so universally admired, . . . The many effusions from the pen of this gentleman independent of his vocal powers, is sufficient proof of his being a man of considerable talent and originality—you should hear him sing his national air "on a wing that beamed in glory" [and it would be] unnecessary for us to enlarge on his merits as a vocalist—for his Melodies display a feeling of Patriotism which attracts the attention of every beholder.

Dandy

A dandy is a man who places particular importance upon physical appearance, refined language, and leisurely hobbies, pursued with the appearance of nonchalance in a cult of Self...

" trying to fit into Northern white society, "Zip Coon" garnered acclaim and quickly became an audience favorite and Dixon's trademark tune. He later claimed to have written the song, although others performed it before him, so this seems unlikely. Dixon accompanied his singing with an earthy jig

Jig

The Jig is a form of lively folk dance, as well as the accompanying dance tune, originating in England in the 16th century and today most associated with Irish dance music and Scottish country dance music...

.

On July 7, the Farren Riots

Anti-abolitionist riots (1834)

The Anti-abolitionist riots of 1834, also known simplistically as the Farren Riots, occurred in New York City over a series of four nights, beginning on July 7, 1834...

erupted. Young men in New York City targeted the homes, businesses, churches, and institutions of black New Yorkers and abolitionists

Abolitionism

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

. On the night of July 9, the mob stormed the Bowery Theatre. Manager Thomas S. Hamblin

Thomas S. Hamblin

Thomas Sowerby Hamblin was an English actor and theatre manager. He first took the stage in England, then immigrated to the United States in 1825. He received critical acclaim there, and eventually entered theatre management. During his tenure at New York City's Bowery Theatre he helped establish...

failed to quell them, and actor Edwin Forrest

Edwin Forrest

Edwin Forrest was an American actor.-Early life:Forrest was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, of Scottish and German descent. His father died and he was brought up by his mother, a German woman of humble origins. He was educated at the common schools in Philadelphia, and early evinced a taste...

did not meet their expectations when they ordered him to perform. According to the New York Sun

New York Sun (historical)

The Sun was a New York newspaper that was published from 1833 until 1950. It was considered a serious paper, like the city's two more successful broadsheets, The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune...

:

Mr. Dixon, the singer (an American,) now made his appearance. "Let us have Zip Coon," exclaimed a thousand voices. The singer gave them their favorite song, amidst peals of laughter,—and his Honor the Mayor, who as the old woman said of her husband, is a "good-natured, easy fellow," made his appearance, delivered a short speech, made a low bow, and went out. Dixon, who had produced such amazing good nature with "Zip Coon," next addressed them—and they soon quietly dispersed.

Dixon the editor

In early 1835, Dixon moved to Lowell, MassachusettsLowell, Massachusetts

Lowell is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA. According to the 2010 census, the city's population was 106,519. It is the fourth largest city in the state. Lowell and Cambridge are the county seats of Middlesex County...

, a small town growing out of the Industrial Revolution. By April, he had taken the epithet "The National Melodist" and was editing Dixon's Daily Review. The paper took as motto "Knowledge—Liberty—Utility—Representation—Responsibility" and championed the Whig Party

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

, Radical Republicanism, and the working class. Dixon's Daily Review also explored morality

Morality

Morality is the differentiation among intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and bad . A moral code is a system of morality and a moral is any one practice or teaching within a moral code...

and women's place in the rapidly changing society of the urban North.

Dixon's criticism of his colleagues did not win him any friends, and in June, the Boston Post

Boston Post

The Boston Post was the most popular daily newspaper in New England for over a hundred years before it folded in 1956. The Post was founded in November 1831 by two prominent Boston businessmen, Charles G...

reported that he had "flogged one of the editors of the Lowell Castigator, and was hunting after the other." By the next month, Dixon had sold his paper, and the new publishers were eager to point out that Dixon no longer had anything to do with its production. By August, rumors were circulating that Dixon had started up another paper called the News Letter and was selling it in Lowell and Boston. If he did, no copies are known to have survived.

By February 1836, Dixon was touring again. He played many well-attended shows in Boston that month and did a play at the Tremont Theatre

Tremont Theatre, Boston

The Tremont Theatre on 88 Tremont Street was a playhouse in Boston. A group of wealthy Boston residents financed the building's construction. Architect Isaiah Rogers designed the original Theatre structure in 1827 in the Greek Revival style...

. His recent forays into publishing had soured his image in the popular press, however, and The New York Times

The New York Times

The New York Times is an American daily newspaper founded and continuously published in New York City since 1851. The New York Times has won 106 Pulitzer Prizes, the most of any news organization...

satirized his lower-class audience:

Tremont Teatre. At this classical establishment, Mr Dixon, "the American Buffo singer," is at present the star. His third night is announced! Will some of the enlightened citizens of the emporium favor us with their opinion of his performance? Is his Zip Coon as thrilling as Mr Wood's "Still so gently o'er me stealing?"

On 16 and April 30, Dixon played the Masonic Temple in Boston. There he included material to appeal to his lower-class audience, such as a popular tune that he had adapted with lyrics about the Boston Fire Department

Boston Fire Department

The Boston Fire Department provides fire protection services for Boston, Massachusetts, USA. In addition to fire protection, the Boston Fire department also provides basic emergency medical services and respond to a variety of emergencies such as, but not limited to, motor vehicle accidents,...

. Nevertheless, he also reached out to a richer, middle-class patronage. For example, he played alongside a classically trained pianist, and he billed the performance as a "concert

Concert

A concert is a live performance before an audience. The performance may be by a single musician, sometimes then called a recital, or by a musical ensemble, such as an orchestra, a choir, or a musical band...

", a word typically reserved for high-class, non-blackface entertainment. Dixon earned a third of the gross from this engagement: $23.50. He still owed money to the printer of Dixon's Daily Review, so these earnings were put in trust for the conductor of the orchestra to pick up at a later date. Dixon and the printer grew impatient and presented a forged

Forgery

Forgery is the process of making, adapting, or imitating objects, statistics, or documents with the intent to deceive. Copies, studio replicas, and reproductions are not considered forgeries, though they may later become forgeries through knowing and willful misrepresentations. Forging money or...

note to the trustee to collect early. Within a few days, Dixon was arrested and jailed in Boston. The press took the opportunity to castigate him again: "George Washington Dixon, now cormorant of Boston jail

Leverett Street Jail

The Leverett Street Jail in Boston, Massachusetts served as the city and county prison for some three decades in the mid-19th century. Inmates included John White Webster...

, and ex-publisher, ex-editor, ex-broker, ex-melodist, &c., is quite out of tune." The Boston Courier" called Dixon "the most miserable apology for a vocalist that ever bored the public ear."

At the trial, held in mid-June, character witnesses testified that Dixon was "a harmless, inoffensive man, but destitute of business capacity" and "in reply to the question whether Dixon was non compos mentis

Non compos mentis

Non compos mentis is a term meaning 'not of sound mind'. Non compos mentis derives from the Latin non meaning "not", compos meaning "having ", and mentis , meaning "mind"...

, I consider him as being on the frontier line—sometimes on one side, and sometimes on the other, just as the breeze of fortune happens to blow." In the end, he was found not guilty when the prosecution failed to satisfy that he had known the document to be a forgery. Dixon took the opportunity to give a speech to the public outside. He then returned to the stage, earning a considerable $527.50 in late July.

Dixon was still guilty in the eyes of the press, however, and his letters to clear his name only made things worse:

Mister Zip Coon is at his old tricks again. So far from possessing the ability to write a letter Miss Nancy-Coal-Black-Rose Dixon cannot begin to write ten consecutive words of the English language, and he must have encountered "the Schoolmaster abroad" in the Athenian city that teaches "penmanship in six lessons," and that lately too if he can sign his name.

By the end of 1836, Dixon had moved to Boston and started a new paper, the Bostonian; or, Dixon's Saturday Night Express. The paper focused on working-class issues, religious values, and opposition to abortion

Abortion

Abortion is defined as the termination of pregnancy by the removal or expulsion from the uterus of a fetus or embryo prior to viability. An abortion can occur spontaneously, in which case it is usually called a miscarriage, or it can be purposely induced...

. It followed the lead of the Daily Review in exposing allegedly immoral affairs of well known Bostonians. One story told of two personalities eloping. Other Boston papers called the story false, and the Boston Herald

Boston Herald

The Boston Herald is a daily newspaper that serves Boston, Massachusetts, United States, and its surrounding area. It was started in 1846 and is one of the oldest daily newspapers in the United States...

labeled Dixon a "knave". Dixon fired back, depicting the paper's editor, Henry F. Harrington

Henry F. Harrington

Henry F. Harrington was an American newspaper editor. He edited the Boston Herald for part of the 1830s.In 1837, Harrington delivered a message by train from Worcester to Boston, a distance of 45 miles. The trip took just under an hour. Martin, while appreciative of Harrington's determination,...

, as a monkey.

In early 1837, Dixon was again in legal trouble. Harrington accused Dixon of stealing half a ream of paper from the Morning Post, the principal competition to Harrington's Herald. The judge eventually dismissed the case, agreeing that the paper had been taken, but ruling that no proof pointed to Dixon as the one who had taken it. Dixon gave another post-trial speech, followed by a stage show on February 4.

Not ten days after the end of the Harrington case, Dixon was charged with forging a signature on a bail bond pertaining to his previous debt from July 1835. He was sent to Lowell and jailed. The press responded with its usual glee: "George has been a great eulogist, the defender of the Constitution! But he cannot defend himself." At his hearing on February 15, bail was set at $1000, an unheard of amount for the time. Unable to pay, he was transferred to a jail in Concord, Massachusetts

Concord, Massachusetts

Concord is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the town population was 17,668. Although a small town, Concord is noted for its leading roles in American history and literature.-History:...

.

Dixon's March 16 trial ended in conviction. His appeal to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court is the highest court in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The SJC has the distinction of being the oldest continuously functioning appellate court in the Western Hemisphere.-History:...

on April 17 resulted in a hung jury, and his prosecutors dropped the charges against him. He gave another of his by now trademark post-trial addresses. The Boston Post wrote: "I begin to think that the Melodist bears a charmed life—and as was often said to be done in olden time, has made a bargain with the Being of Darkness for a certain term of years, during which he may defy the majesty of the law, and the wrath of his enemies."

Another stage tour followed, with concerts in Lowell, New England, and Maine. This was an apparent success, with one reviewer saying that Dixon had "a voice which all unite in pronouncing to be of remarkable richness and compass." That Fall, he may have contemplated a tour with James Salisbury, a black musician and dancer well known in lower-class districts of Boston such as Ann Street. Instead, he appeared on December 6 at the upper-class Opera Saloon, singing selections from popular opera

Opera

Opera is an art form in which singers and musicians perform a dramatic work combining text and musical score, usually in a theatrical setting. Opera incorporates many of the elements of spoken theatre, such as acting, scenery, and costumes and sometimes includes dance...

s. His fame (or notoriety) served to get him listed as a candidate for the Boston mayoral race in December. Dixon won nine votes, despite his polite refusal to serve should he be elected.

The Polyanthos

Dixon performed in Boston through the end of February 1838. That spring, he moved to New York City, where he re-entered the publishing business with a newspaper called the Polyanthos and Fire Department Album. Dixon again championed the lower class and aimed to expose the sordid affairs of the rich, especially those who preyed upon lower-class women.An early Polyanthos alleged that Thomas Hamblin, manager of the Bowery Theatre, was engaging in an affair with Miss Missouri, a teen-aged performer there. Within ten days of publication, Miss Missouri turned up dead, reportedly killed by "inflammation of the brain caused by the violent misconduct of Miss Missouri's mother and the publication of an abusive article in The Polyanthos." On July 28, Hamblin accosted Dixon. Another assault in August prompted Dixon to start carrying a pistol. Undaunted, Dixon continued his attacks on Hamblin and others in the Polyanthos. He exposed another alleged affair, this between a merchant named Rowland R. Minturn and the wife of a shipmaker named James H. Roome. Twelve days after the publication, Roome killed himself.

Another article alleged that Francis L. Hawks

Francis L. Hawks

Dr. Francis Lister Hawks was an American priest of the Episcopal Church, and a politician in North Carolina....

, an Episcopalian rector and reverend at the St. Thomas Church of New York, had been engaging in illicit sexual behavior. On December 31, Dixon was in court, charged with libel

Slander and libel

Defamation—also called calumny, vilification, traducement, slander , and libel —is the communication of a statement that makes a claim, expressly stated or implied to be factual, that may give an individual, business, product, group, government, or nation a negative image...

. Dixon spent a week in jail, then paid the $2000 bail. However, before he could even leave the jailhouse, he was arrested for a charge leveled by Rowland Minturn's brothers that Dixon's article had resulted in the man's death.

Bail was raised to $9000, an enormous amount, which Dixon protested. The prosecution argued that "The accused is a criminal of the blackest dye, and by his infamous publication is morally guilty of no less than three murders, and I hope the court will not diminish the amount of bail one iota!" It did not. Nevertheless, a notorious New York madam named Adeline Miller

Adeline Miller

Adeline Miller, alias Adeline Furman, was an American madam and prostitute. According to her contemporary George Templeton Strong, Miller had been active in New York City prostitution since the late 1810s. By 1821, she was running a bordello on Church Street, where she had accumulated personal...

paid it, and Dixon walked free. Only a month later, though, she had sent Dixon back to jail for unknown reasons. Facing seven counts (four from Hawks and three from the Minturns), the singer and editor remained incarcerated for two months while he awaited trial.

The Minturn case came first, on April 15, 1839. After three days, the jury came back unable to reach a verdict, and the Minturn brothers dropped the charges. Dixon returned to jail, but Hawks dropped his charges from four to three. The judge lowered bail to $900 on April 20, and Dixon walked free.

The press renewed their attacks on him:

To those who know the true character, and something of the personal history of this imbecile vagrant, the exuberance of indignation with which he is pursued, appears truly ridiculous. That he is disgusting, a nuisance, and a bore, we know—and so is a spider. Nobody would dream, however, of extinguishing the latter insect with a park of artillery; though all the city seem to have fancied that George Washington Dixon could be conquered with no less. The truth of him is, that he is a most unmitigated fool; and as to his pursuing any person with malice, he is not capable of any sentiment requiring the appreciation of real or fancied injury. If he were kicked down stairs, he could not decide, until told by some one else, whether the kick was the result of accident or design, and if design, whether it was intended as a compliment or an insult.

Dixon fought back in the Polyanthos by defending himself and his motives, and to some degree, he seems to have succeeded. The Herald for one admitted that his trial had exposed an unsavory facet of the upper class. Nevertheless, on May 10, Dixon changed his plea to guilty regarding one count, and the next day did the same for the other two. He was sentenced to six months of hard labor at the New York State Penitentiary at Blackwell's Island

Roosevelt Island

Roosevelt Island, known as Welfare Island from 1921 to 1973, and before that Blackwell's Island, is a narrow island in the East River of New York City. It lies between the island of Manhattan to its west and the borough of Queens to its east...

. Dixon reportedly responded, "This is a pretty situation for an editor." He would later claim that Hawks had paid him $1000 to change his plea.

Dixon is a mulatto, and was, not many years ago, employed in this city, in an oyster house to open oysters and empty the shells into the carts before they were carried away. He is an impudent scoundrel, aspires to every thing, and was fit to be any body's fool. Somebody used his name (such as he called himself, for negroes have, by right, no surnames) as the publisher of a newspaper, in which every body, almost, was libelled. He is now caged, and, we may hope, will, when he comes out of prison, go to opening oysters, or some other employment appropriate to his habits and color.

Dixon served out his sentence then returned to New York. He resumed the Polyanthos, emerging as the leader of a cadre of like-minded editors interested in exposing immorality. Dixon now focused his efforts on Austrian dancer Fanny Elssler

Fanny Elssler

Fanny Elssler - 27 November 1884), born Franziska Elßler, was an Austrian ballerina of the 'Romantic Period'.- Life :Daughter of Johann Florian Elssler, a second generation employee of Prince Esterhazy in Eisenstadt. Both Johann and his brother Josef were employed as copyists to the Prince's...

, whom he accused of sexual misconduct. On August 21, 1840, he went so far as to rally a riot against her and then published the inciting speech in the Polyanthos. He then targeted men who seduced young, working-class women, boarders who cheated their landlords, dysfunctional banks, and so-called British agents who were supposedly stirring up anti-American sentiment among American Indians and black slaves. Dixon claimed to be "a battering-ram against vice and folly in every shape", writing:

The Polyanthos cannot die. The protecting Providence that watches over the safety of the just, and defeats the machinations of the wicked, will make it bloom. . . . We prophesy that the latest descendant of the youngest newsboy will animate his hearers with the desire to emulate the enviable fame of DIXON! Our name will be handed down to the end of time as one of the most independent men of the nineteenth century! Our very hat will become a relic.

Abortion

Abortion is defined as the termination of pregnancy by the removal or expulsion from the uterus of a fetus or embryo prior to viability. An abortion can occur spontaneously, in which case it is usually called a miscarriage, or it can be purposely induced...

ist known as Madame Restell

Madame Restell

Ann Trow , better known as Madame Restell, was an early-19th-century abortionist who practiced in New York City.-Biography:...

. He vowed to reprint an anti-Restell editorial every week until the authorities took notice or Restell stopped running newspaper ads for her abortion services. As for abortion itself, Dixon claimed that it subverted marriage by inhibiting procreation and encouraged female infidelity.

Dixon kept his word, illustrating the editorial in later runs with woodcuts of Restell carrying a skull-and-crossbones emblem. When the March 17 New York Courier quoted the New York grand jury as saying "We earnestly pray that if there is no law that will reach this [Madame Restell], which we present as a public nuisance, the court will take measures for procuring the passage of such a law", Dixon responded with the March 20 headline "Restell caught at last!" On March 22, Ann Lohman, part of the husband-and-wife team behind the Restell name, was arrested. Dixon claimed vindication and covered the trial over several issues of the Polyanthos. After her conviction on July 20, he wrote, "the monster in human shape . . . has . . . been convicted of one of the most hellish acts ever perpetrated in a Christian land!"

On September 12, a man in the street struck Dixon in the head with an ax, which prompted some of the only positive press Dixon ever enjoyed that was not related to his singing. The Uncle Sam praised his editing and writing: "Go on martyr of virtue, go on and prosper! Go on getting out extras, and defending the sacredness of the marriage institution. Go on through malice, opposition, fiery trials, persecutions and assassinations—posterity will do thee justice. . . !"

Even with positive press, Dixon's troubles with the courts were not over. Around September 16, he allegedly assaulted Peter D. Formal, who was taking down bills that Dixon had posted. Dixon failed to appear for his October court date, and he skipped later dates on 1 and November 11. On November 19, he again was placed under arrest for obscenity

Obscenity

An obscenity is any statement or act which strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time, is a profanity, or is otherwise taboo, indecent, abhorrent, or disgusting, or is especially inauspicious...

as part of a citywide campaign by the district attorney to fight yellow journalism

Yellow journalism

Yellow journalism or the yellow press is a type of journalism that presents little or no legitimate well-researched news and instead uses eye-catching headlines to sell more newspapers. Techniques may include exaggerations of news events, scandal-mongering, or sensationalism...

. On January 13, 1842, Dixon was indicted for the charges in absentia. A warrant was issued for his arrest on April 13. By this time, he had handed the Polyanthos to Louse Leah, and the charges were eventually dropped.

In late 1841, Dixon had gotten into another row with a colleague. William Joseph Snelling

William Joseph Snelling

William Joseph Snelling was an American adventurer, writer, poet, and journalist. His short stories about American Indian life were the first to attempt to accurately portray the Plains Indians and among the first attempts at realism by an American writer...

obtained a warrant against him, and Dixon countersued. Snelling wrote anonymously in the Flash:

We know him for a greedy, sordid, unscrupulous knave, of old; . . . We are aware that men are judged by the company they keep and that we shall be blamed for having had anything to do with Dixon. Be it so.—We deserve rebuke, we have suffered for our folly and, if that is not enough, we are content to sit down in sackcloth and ashes; the meet attire of fools who trust to a person so vile that the English language cannot express his unmitigated baseness.

In keeping with sexual morality at the time, Dixon and his colleagues sometimes checked bordellos for cleanliness, friendliness, and other factors. Snelling drew from this, linking Dixon to organized prostitution

Prostitution

Prostitution is the act or practice of providing sexual services to another person in return for payment. The person who receives payment for sexual services is called a prostitute and the person who receives such services is known by a multitude of terms, including a "john". Prostitution is one of...

and alleging that he had connections to a madam named Julia Brown

Julia Brown

Julia Brown was an American madam and prostitute active in mid-nineteenth century New York City. Brown has been described as "the best-known prostitute in antebellum America". She became a popular subject of tourist guidebooks, and her name appears often in diaries from the period.In the 1830s,...

. Eventually, another editor named George B. Wooldridge

George B. Wooldridge

George B. Wooldridge was the business manager of the first blackface minstrel troupe, the Virginia Minstrels, in the mid-19th century. He sometimes went by the name Tom Quick.-References:...

joined with Dixon for a few issues of the True Flash, but they did not sell well. Rumors circulated at this time that Dixon was to be married, but sources disagreed over the identity of the fiancée; one said she was a Congressman's daughter, another that she was a madam. The Flash published a story that Julia Brown and a prostitute named Phoebe Doty

Phoebe Doty

Phoebe Doty was an American madam and prostitute. In 1821, she entered a bordello in the Five Points neighborhood of New York City. Over the next three years, she accrued $600 in personal belongings. For the next decade or so, Doty moved from house to house, eventually settling in a brothel on...

had been seen fighting over the Melodist. If Dixon did marry, no record survives of it.

Later career

Beginning in 1842, Dixon took on a number of new occupations, including animal magnetistAnimal magnetism

Animal magnetism , in modern usage, refers to a person's sexual attractiveness or raw charisma. As postulated by Franz Mesmer in the 18th century, the term referred to a supposed magnetic fluid or ethereal medium believed to reside in the bodies of animate beings...

and spiritualist specializing in clairvoyance

Clairvoyance

The term clairvoyance is used to refer to the ability to gain information about an object, person, location or physical event through means other than the known human senses, a form of extra-sensory perception...

. A fad for public competitions and feats of endurance served as another vehicle for him to keep his name in the public eye; he became a "pedestrian", a long-distance sport walker

Race walking

Racewalking, or race walking, is a long-distance athletic event. Although it is a foot race, it is different from running in that one foot must appear to be in contact with the ground at all times...

. The participation of Dixon, a blackface singer and dancer, in these contests presaged the challenge dances of performers such as Master Juba

Master Juba

Master Juba was an African American dancer active in the 1840s. He was one of the first black performers in the United States to play onstage for white audiences and the only one of the era to tour with a white minstrel group...

and John Diamond

John Diamond (dancer)

John Diamond , aka Jack or Johnny, was an Irish-American dancer and blackface minstrel performer. Diamond entered show business at age 17 and soon came to the attention of circus promoter P. T. Barnum. In less than a year, Diamond and Barnum had a falling-out, and Diamond left to perform with other...

in the next few years.

In February, he competed to win $4000 by walking 48 hours without stopping. When the prize failed to materialize, Dixon charged admission to watch him. Later that month, Dixon tried to break this record by walking 50 hours. His publicity was, as usual, bad. Brother Jonathan

Brother Jonathan

Brother Jonathan was a fictional character created to personify the entire United States, in the early days of the country's existence.In editorial cartoons and patriotic posters, Brother Jonathan was usually depicted as a typical American revolutionary, with tri-cornered hat and long military jacket...

gave this advice: "walk in one direction all the time, from this part of the compass, till ocean fetches him up, and then see how far he can swim." He walked for 60 hours that summer in Richmond, then did 30 miles (48.3 km) in five hours and 35 minutes in Washington, D.C. Dixon tried many other feats of endurance. For example, in late August, he stood on a plank for three days and two nights with no sleep. In September, he paced for 76 hours on a 15-foot-long (five-meter) platform.

Meanwhile, he did not give up his singing career. In early 1843, Dixon (now called "Pedestrian and Melodist") appeared at least once more at the Bowery Theatre, and he played on bills with Richard Pelham

Richard Pelham

Richard Ward "Dick" Pelham , born Richard Ward Pell, was an American blackface performer. He was born in New York City....

, George Rice, and Billy Whitlock

Billy Whitlock

William M. "Billy" Whitlock was an American blackface performer. He began his career in entertainment doing blackface banjo routines in circuses and dime shows, and by 1843, he was well known in New York City. He is best known for his role in forming the original minstrel troupe, the Virginia...

. On January 29, he performed at a benefit for Dan Emmett

Dan Emmett

Daniel Decatur "Dan" Emmett was an American songwriter and entertainer, founder of the first troupe of the blackface minstrel tradition.-Biography:...

. These concerts would be his last.

Despite these excursions into athletics and entertainment, Dixon still considered himself an editor. He started a new paper called Dixon's Regulator by March, and he renewed his public crusade in New York. On February 22, 1846, he posted handbills around the city publicizing a meeting to protest further activities by Madame Restell. At the rally the next day, several hundred people listened to Dixon speak against the abortionist, calling for her neighbors to demand her eviction or else to take matters into their own hands. The crowd then walked to her residence three blocks away to shout threats but eventually dispersed. Restell responded with a letter to the New York Tribune

New York Tribune

The New York Tribune was an American newspaper, first established by Horace Greeley in 1841, which was long considered one of the leading newspapers in the United States...

and New York Herald

New York Herald

The New York Herald was a large distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between May 6, 1835, and 1924.-History:The first issue of the paper was published by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., on May 6, 1835. By 1845 it was the most popular and profitable daily newspaper in the UnitedStates...

alleging that Dixon was simply trying to extort money from her in return for an end to his agitation:

Again and again have I been applied to by his emissaries for money, and as often have they been refused; and, as a consequence, I have been vilified and abused without stint or measure, which, of course, I expected, and, of the two, would prefer to his praise.

During the Mexican-American War, Dixon added some timely political references to "Zip Coon" and briefly returned to the public eye. Another crusade seems to have drawn Dixon away from New York in 1847. He was probably one of the first Radical Republicans to entrench himself as a filibuster

Filibuster (military)

A filibuster, or freebooter, is someone who engages in an unauthorized military expedition into a foreign country to foment or support a revolution...

in the Yucatán

Yucatán

Yucatán officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Yucatán is one of the 31 states which, with the Federal District, comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 106 municipalities and its capital city is Mérida....

in a bid to annex more territory for the United States.

Dixon retired to New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana. The New Orleans metropolitan area has a population of 1,235,650 as of 2009, the 46th largest in the USA. The New Orleans – Metairie – Bogalusa combined statistical area has a population...

, sometime before 1848. A city directory gives his address as "Literary Tent", and his obituary in the Baton Rouge Daily Gazette and Comet states that the Poydras Market

Poydras Market

The Poydras Market also known as the Poydras Street Market, was an early market area in New Orleans, Louisiana.It was located on Poydras Street across from Maylie's Restaurant...

"by night and day, was the home of this waif upon society . . . . The 'General' was not without friends who contributed an odd 'five' to him when too frail to move about." He came down with pulmonary tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

sometime in mid-1860. On February 27, 1861, he checked into the New Orleans Charity Hospital, noting his occupation as "editor". Dixon died on March 2.