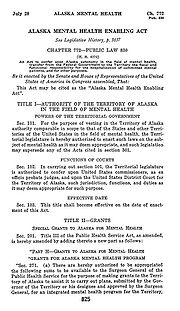

Alaska Mental Health Enabling Act

Encyclopedia

Public law

Public law is a theory of law governing the relationship between individuals and the state. Under this theory, constitutional law, administrative law and criminal law are sub-divisions of public law...

84-830) was an Act of Congress

Act of Congress

An Act of Congress is a statute enacted by government with a legislature named "Congress," such as the United States Congress or the Congress of the Philippines....

passed to improve mental health

Mental health

Mental health describes either a level of cognitive or emotional well-being or an absence of a mental disorder. From perspectives of the discipline of positive psychology or holism mental health may include an individual's ability to enjoy life and procure a balance between life activities and...

care in the United States territory

Alaska Territory

The Territory of Alaska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 24, 1912, until January 3, 1959, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Alaska...

of Alaska

Alaska

Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area. It is situated in the northwest extremity of the North American continent, with Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, with Russia further west across the Bering Strait...

. It became the focus of a major political controversy after opponents nicknamed it the "Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

Bill" and denounced it as being part of a communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

plot to hospitalize and brainwash Americans. Campaigners asserted that it was part of an international Jewish, Roman Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

or psychiatric

Psychiatry

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the study and treatment of mental disorders. These mental disorders include various affective, behavioural, cognitive and perceptual abnormalities...

conspiracy intended to establish United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

-run concentration camps in the United States.

The legislation in its original form was sponsored by the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

, but after it ran into opposition, it was rescued by the conservative Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

Senator Barry Goldwater

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater was a five-term United States Senator from Arizona and the Republican Party's nominee for President in the 1964 election. An articulate and charismatic figure during the first half of the 1960s, he was known as "Mr...

. Under Goldwater's sponsorship, a version of the legislation without the commitment provisions that were the target of intense opposition from a variety of far-right, anti-Communist and fringe religious groups was passed by the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

. The controversy still plays a prominent role in the Church of Scientology

Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology is an organization devoted to the practice and the promotion of the Scientology belief system. The Church of Scientology International is the Church of Scientology's parent organization, and is responsible for the overall ecclesiastical management, dissemination and...

's account of its campaign against psychiatry

Scientology and psychiatry

Scientology and psychiatry have come into conflict since the foundation of Scientology in 1952. Scientology is publicly, and often vehemently, opposed to both psychiatry and psychology. Scientologists view psychiatry as a barbaric and corrupt profession and encourage alternative care based on...

.

The Act succeeded in its initial aim of establishing a mental health care system for Alaska, funded by income from lands allocated to a mental health trust. However, during the 1970s and early 1980s, Alaskan politicians systematically stripped the trust of its lands, transferring the most valuable land to private individuals and state agencies. The resulting drop in funding led to a severe effect on the provision of mental health care in Alaska. The asset-stripping was eventually ruled to be illegal following several years of litigation, and a reconstituted mental health trust was established in the mid-1980s.

Background to the act

U.S. state

A U.S. state is any one of the 50 federated states of the United States of America that share sovereignty with the federal government. Because of this shared sovereignty, an American is a citizen both of the federal entity and of his or her state of domicile. Four states use the official title of...

, being constituted instead as a territory of the United States

United States territory

United States territory is any extent of region under the jurisdiction of the federal government of the United States, including all waters including all U.S. Naval carriers. The United States has traditionally proclaimed the sovereign rights for exploring, exploiting, conserving, and managing its...

. The treatment of the mentally ill was governed by an agreement with the state of Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

dating back to the turn of the 20th century. On June 6, 1900, the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

enacted a law permitting the government of the then District of Alaska

District of Alaska

The District of Alaska was the governmental designation for Alaska from May 17, 1884 to August 24, 1912, when it became Alaska Territory. Previously it had been known as the Department of Alaska. At the time, legislators in Washington, D.C., were occupied with post-Civil War reconstruction issues,...

to provide mental health care for Alaskans. In 1904, a contract was signed with Morningside Hospital, privately owned and operated by Henry Waldo Coe

Henry Waldo Coe

Henry Waldo Coe was a United States frontier physician and politician.Coe was born in Waupun, Wisconsin, to Dr. Samuel Buel Coe and his wife Mary Jane...

in Portland, Oregon

Portland, Oregon

Portland is a city located in the Pacific Northwest, near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2010 Census, it had a population of 583,776, making it the 29th most populous city in the United States...

, under which Alaskan mental patients would be sent to the hospital for treatment. A commitment regime was established under which a person said to be mentally ill was to be brought before a jury of six people, who would rule him sane or insane. The patient was routinely sent to prison until his release or transfer to Portland; at no point in this ruling was a medical or psychiatric examination required.

By the 1940s it was recognized that this arrangement was unsatisfactory. The American Medical Association

American Medical Association

The American Medical Association , founded in 1847 and incorporated in 1897, is the largest association of medical doctors and medical students in the United States.-Scope and operations:...

conducted a series of studies in 1948, followed by a Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior is the United States federal executive department of the U.S. government responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land and natural resources, and the administration of programs relating to Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native...

study in 1950. They highlighted the deficiencies of the program: commitment procedures in Alaska were archaic, and the long trip to Portland had a negative effect on patients and their families. In addition, an audit of the hospital contract found that the Sanatorium Company, which owned the hospital, had been padding its expenses. This had enabled it to make an excess profit of $69,000 per year (equivalent to over $588,000 per year at 2007 prices).

The studies recommended a comprehensive overhaul of the system, with the development of an in-state mental health program for Alaska. This proposal was widely supported by the public and politicians. At the start of 1956, in the second session of the 84th Congress

84th United States Congress

The Eighty-fourth United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from January 3, 1955 to January 3, 1957, during the third and...

, Representative Edith Green

Edith Green

Edith Louise Starrett Green was an American politician and educator in the state of Oregon. A native of South Dakota, she was raised in Oregon and completed her education at the University of Oregon and Stanford University...

(D-Oregon) introduced the Alaska Mental Health Bill (H.R. 6376) in the House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

. The bill had been written by Bob Bartlett, the Congressional Delegate

Delegate (United States Congress)

A delegate to Congress is a non-voting member of the United States House of Representatives who is elected from a U.S. territory and from Washington, D.C. to a two-year term. While unable to vote in the full House, a non-voting delegate may vote in a House committee of which the delegate is a member...

from the Alaska Territory who later became a U.S. Senator. Senator Richard L. Neuberger

Richard L. Neuberger

Richard Lewis Neuberger was a U.S. journalist, author, and politician during the middle of the 20th century. A native of Oregon, he would write for The New York Times before and after a stint in the United States Army during World War II...

(D-Oregon) sponsored an equivalent bill, S. 2518, in the Senate.

Details of the bill

The Alaska Mental Health Bill's stated purpose was to "transfer from the Federal GovernmentFederal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

to the Territory of Alaska basic responsibility for the hospitalization, care and treatment of the mentally ill of Alaska." In connection with this goal, it aimed:

- to modernize procedures for such hospitalization (including commitment), care, and treatment and to authorize the Territory to modify or supersede such procedures;

- to assist in providing for the Territory necessary facilities for a comprehensive mental-health program in Alaska, including inpatient and outpatient facilities;

- to provide for a land grant to the Territory to assist in placing the program on a firm long-term basis; and

- to provide for a ten-year program, of grants-in-aid to the Territory to enable the Territory gradually to assume the full operating costs of the program.

The bill provided for a cash grant of $12.5 million (about $94 million at 2007 prices) to be disbursed to the Alaskan government in a number of phases, to fund the construction of mental health facilities in the territory. To meet the ongoing costs of the program, the bill transferred one million acres (4,000 km²) of federally-owned land in Alaska to the ownership of the proposed new Alaska Mental Health Trust as a grant-in-aid

Grant-in-aid

A grant-in-aid is money coming from central government for a specific project. This kind of funding is usually used when the government and parliament have decided that the recipient should be publicly funded but operate with reasonable independence from the state.In the United Kingdom, most bodies...

—the federal government owned about 99% of the land of Alaska at the time. The trust would then be able to use the assets of the transferred land (principally mineral

Mineral rights

- Mineral estate :Ownership of mineral rights is an estate in real property. Technically it is known as a mineral estate and often referred to as mineral rights...

and forestry

Forestry

Forestry is the interdisciplinary profession embracing the science, art, and craft of creating, managing, using, and conserving forests and associated resources in a sustainable manner to meet desired goals, needs, and values for human benefit. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands...

rights) to obtain an ongoing revenue stream to fund the Alaskan mental health program. Similar provisions had applied in other US territories to support the provision of public facilities prior to the achievement of statehood.

In addition, the bill granted the Governor of Alaska authority to enter into reciprocal mental health treatment agreements with the governors of other states. Alaskans who became mentally ill in the lower 48 states would be properly treated locally until they could be returned to Alaska; likewise, citizens of the lower 48 who fell mentally ill in Alaska would receive care there, before being returned to their home states.

The bill was seen as entirely innocuous when it was introduced on January 16, 1956. It enjoyed bipartisan support, and on January 18 it was passed unanimously by the House of Representatives. It then fell to the Senate to consider the equivalent bill in the upper chamber, S. 2518, which was expected to have an equally untroubled passage following hearings scheduled to begin on February 20.

Sounding the alarm

Southern California

Southern California is a megaregion, or megapolitan area, in the southern area of the U.S. state of California. Large urban areas include Greater Los Angeles and Greater San Diego. The urban area stretches along the coast from Ventura through the Southland and Inland Empire to San Diego...

, the American Public Relations Forum

American Public Relations Forum

The American Public Relations Forum was a conservative anti-communist organization for Catholic women, established in southern California in 1952 with its headquarters in Burbank...

(APRF), issued an urgent call to arms in its monthly bulletin. It highlighted the proposed text of the Alaska Mental Health Bill, calling it "one that tops all of them". The bulletin writers commented: "We could not help remembering that Siberia is very near Alaska and since it is obvious no one needs such a large land grant, we were wondering if it could be an American Siberia." They said that the bill "takes away all of the rights of the American citizen to ask for a jury trial and protect him[self] from being railroaded to an asylum by a greedy relative or 'friend' or, as the Alaska bill states, 'an interested party'."

The APRF had a history of opposing mental health legislation; earlier in 1955, it had played a key role in stalling the passage of three mental health bills in the California Assembly

California State Assembly

The California State Assembly is the lower house of the California State Legislature. There are 80 members in the Assembly, representing an approximately equal number of constituents, with each district having a population of at least 420,000...

. It was part of a wider network of far-right organizations which opposed psychiatry and psychology

Psychology

Psychology is the study of the mind and behavior. Its immediate goal is to understand individuals and groups by both establishing general principles and researching specific cases. For many, the ultimate goal of psychology is to benefit society...

as being pro-communist, anti-American

Anti-Americanism

The term Anti-Americanism, or Anti-American Sentiment, refers to broad opposition or hostility to the people, policies, culture or government of the United States...

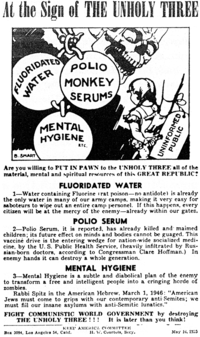

, anti-Christian and pro-Jewish. The Keep America Committee, another Californian "superpatriot" group, summed up the anti-mental health mood on the far right in a pamphlet issued in May 1955. Calling "mental hygiene" part of the "unholy three" of the "Communistic World Government", it declared: "Mental Hygiene is a subtle and diabolical plan of the enemy to transform a free and intelligent people into a cringing horde of zombies".

The APRF's membership overlapped with that of the much larger Minute Women of the U.S.A.

Minute Women of the U.S.A.

The Minute Women of the U.S.A. was one of the largest of a number of anti-communist women's groups that were active during the 1950s and early 1960s...

, a nationwide organization of militant anti-communist housewives which claimed up to 50,000 members across the United States. In mid-January 1956, Minute Woman Leigh F. Burkeland of Van Nuys, California

Van Nuys, Los Angeles, California

Van Nuys is a neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley region of Los Angeles, California.-History:Look at the two photos of Van Nuys' first year—and then listen to what the Los Angeles Times wrote on February 23, 1911, the day after the Van Nuys town lot auction--"Between dawn and dusk, in the...

issued a bulletin protesting against the bill. It was mimeographed by the California State Chapter of the Minute Women and mailed across the nation. On January 24, 1956, the strongly anti-Statist Santa Ana Register newspaper reprinted Burkeland's statement under the headline, "Now — Siberia, U.S.A." Burkeland issued a lurid warning of what the future might hold if the Alaska Mental Health Bill was passed by the Senate:

Fanning the flames

After the Santa Ana Register published its article, a nationwide network of activists began a vociferous campaign to torpedo the Alaska Mental Health Bill. The campaigners included, among other groups and individuals, the white supremacist Rev. Gerald L. K. SmithGerald L. K. Smith

Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith was an American clergyman and political organizer, who became a leader of the Share Our Wealth movement during the Great Depression and later the Christian Nationalist Crusade...

; Women for God and Country; the For America League; the Minute Women of the U.S.A.; the right-wing agitator Dan Smoot

Dan Smoot

Howard Drummond Smoot , better known as Dan Smoot, was an FBI agent and a conservative political activist...

; the anti-Catholic former US Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

Brigadier General Herbert C. Holdridge

Herbert C. Holdridge

Herbert Charles Holdridge was an American military officer, who was best known for being the only United States Army General to retire during World War II, and for having several times sought presidential nominations on fringe party tickets after retirement. He was the father of diplomat John H...

; and L. Ron Hubbard

L. Ron Hubbard

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard , better known as L. Ron Hubbard , was an American pulp fiction author and religious leader who founded the Church of Scientology...

's Church of Scientology, which had been founded only two years earlier.

Increasingly strong statements were made by the bill's opponents through the course of the spring and summer of 1956. In his February 17 bulletin, Dan Smoot told his subscribers: "I do not doubt that the Alaska Mental Health Act was written by sincere, well-intentioned men. Nonetheless, it fits into a sinister pattern which has been forming ever since the United Nations was organized." Dr. George A. Snyder

George Snyder

George Elmer Snyder was the Maryland State Senate majority leader from 1971-1974.He graduated from the University of Maryland and attended the University of Maryland School of Law. He is married to Karen Englehart Snyder and has six children and ten grandchildren...

of Hollywood

Hollywood, Los Angeles, California

Hollywood is a famous district in Los Angeles, California, United States situated west-northwest of downtown Los Angeles. Due to its fame and cultural identity as the historical center of movie studios and movie stars, the word Hollywood is often used as a metonym of American cinema...

sent a letter to all members of Congress in which he demanded an investigation of the Alaska Mental Health Bill's proponents for "elements of treason against the American people behind the front of the mental health program." The Keep America Committee of Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles , with a population at the 2010 United States Census of 3,792,621, is the most populous city in California, USA and the second most populous in the United States, after New York City. It has an area of , and is located in Southern California...

similarly called the proponents of the bill a "conspiratorial gang" that ought to be "investigated, impeached, or at least removed from office" for treason. Retired brigadier general Herbert C. Holdridge

Herbert C. Holdridge

Herbert Charles Holdridge was an American military officer, who was best known for being the only United States Army General to retire during World War II, and for having several times sought presidential nominations on fringe party tickets after retirement. He was the father of diplomat John H...

sent a public letter to President Dwight Eisenhower on March 12, in which he called the bill "a dastardly attempt to establish a concentration camp in the Alaskan wastes." He went on:

This bill establishes a weapon of violence against our citizenry far more wicked than anything ever known in recorded history — far worse than the Siberian prison camps of the CzarTsarTsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

s or the Communists, or the violence of the Spanish InquisitionSpanish InquisitionThe Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition , commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition , was a tribunal established in 1480 by Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. It was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms, and to replace the Medieval...

… The plot of wickedness revealed in this bill fairly reeks of the evil odor of the black forces of the JesuitsSociety of JesusThe Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

who dominate the VaticanHoly SeeThe Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

, and, through officiates in our Government, dominate our politics.

For their part, America's professional health associations (notably the American Medical Association and American Psychiatric Association

American Psychiatric Association

The American Psychiatric Association is the main professional organization of psychiatrists and trainee psychiatrists in the United States, and the most influential worldwide. Its some 38,000 members are mainly American but some are international...

) came out in favour of the bill. There was some initial opposition from the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons

Association of American Physicians and Surgeons

The Association of American Physicians and Surgeons is a politically conservative American non-profit organization founded in 1943 to "fight socialized medicine and to fight the government takeover of medicine." The group was reported to have approximately 4,000 members in 2005, and 3,000 in...

, a small and extremely conservative body which opposed socialized medicine

Socialized medicine

Socialized medicine is a term used to describe a system for providing medical and hospital care for all at a nominal cost by means of government regulation of health services and subsidies derived from taxation. It is used primarily and usually pejoratively in United States political debates...

; Dr. L. S. Sprague

Sprague

Sprague is a surname of English origin, from the northern Middle English Spragge, either a personal name or a byname meaning "lively", a metathesized and voiced form of Spark, a Northern English surname from the Old Norse byname or personal name Sparkr ‘sprightly’, ‘vivacious’.- Places :Canada*...

of Tucson, Arizona

Tucson, Arizona

Tucson is a city in and the county seat of Pima County, Arizona, United States. The city is located 118 miles southeast of Phoenix and 60 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border. The 2010 United States Census puts the city's population at 520,116 with a metropolitan area population at 1,020,200...

said in its March 1956 newsletter that the bill widened the definition of mental health to cover "everything from falling hair to ingrown toenails." However, the association modified its position after it became clear that the AMA took the opposite view.

By March 1956, it was being said in Washington, D.C. that the amount of correspondence on the bill exceeded anything seen since the previous high-water mark of public controversy, the Lend-Lease Act of 1941. Numerous letter-writers protested to their Congressional representatives that the bill was "anti-religious

Antireligion

Antireligion is opposition to religion. Antireligion is distinct from atheism and antitheism , although antireligionists may be atheists or antitheists...

" or that the land to be transferred to the Alaska Mental Health Trust would be fenced off and used as a concentration camp for the political enemies of various state governors. The well-known broadcaster Fulton Lewis

Fulton Lewis

Fulton Lewis, Jr. was a prominent conservative American radio broadcaster from the 1930s to the 1960s.-Early life and career:...

described how he had "received, literally, hundreds of letters protesting bitterly against the bill. I have had telephone calls to the same effect from California, Texas and other parts of the country. Members of Congress report identical reactions." A letter printed in the Daily Oklahoman newspaper in May 1956 summed up many of the arguments made by opponents of the bill:

During February and March 1956, hearings were held before the Senate Subcommittee on Territories and Insular Affairs

United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

The United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources has jurisdiction over matters related to energy and nuclear waste policy, territorial policy, native Hawaiian matters, and public lands....

. Proponents and opponents of the bill faced off in a series of tense exchanges, with strong accusations being made against the people and groups involved in the bill's introduction. Stephanie Williams of the American Public Relations Forum said that the bill would enable Russia to reclaim its former Alaskan territory: "[it] contains nothing to prevent Russia from buying the entire million acres — they already say Alaska belongs to them."

Mrs. Ernest W. Howard of the Women's Patriotic Committee on National Defense castigated the slackness of Congress for not picking up on the bill's perceived dangers: "Those of us who have been in the study and research work of the United Nations, we feel that we are experts in this . . . you as Senators with all the many commitments and the many requirements, are not able to go into all these things." John Kaspar, a White Citizens' Council

White Citizens' Council

The White Citizens' Council was an American white supremacist organization formed on July 11, 1954. After 1956, it was known as the Citizens' Councils of America...

organizer who had achieved notoriety for starting a race riot in Clinton, Tennessee

Clinton, Tennessee

Clinton is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, United States. Its population was 9,409 at the United States Census, 2000. It is the county seat of Anderson County. Clinton is included in the "Knoxville, Tennessee Metropolitan Statistical Area".-Geography:...

, declared that "almost one hundred percent of all psychiatric therapy is Jewish and about eighty percent of psychiatrists are Jewish . . . one particular race is administering this particular thing." He argued that Jews were nationalists of another country who were attempting to "usurp American nationality."

Passing the bill

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

gave the bill its unanimous support, issuing a statement declaring: "As Christian citizens of Alaska we believe this is a progressive measure for the care and treatment of the mentally ill of Alaska. We deplore the present antiquated methods of handling our mentally ill." It also urged the National Council of Churches

National Council of Churches

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA is an ecumenical partnership of 37 Christian faith groups in the United States. Its member denominations, churches, conventions, and archdioceses include Mainline Protestant, Orthodox, African American, Evangelical, and historic peace...

to mobilize support for the bill. An overwhelming majority of senators of both parties were also supportive. The bill's original author, Alaska Delegate Bob Bartlett, spoke for many of the bill's proponents when he expressed his bafflement at the response that it had received:

I am completely at a loss in attempting to fathom the reasons why certain individuals and certain groups have now started a letter-writing campaign … to defeat the act. I am sure that if the letter writers would consult the facts, they would join with all others not only in hoping this act would become law but in working for its speedy passage and approval.

Other senators expressed similar mystification at the agitation against the bill. Senator Henry M. Jackson

Henry M. Jackson

Henry Martin "Scoop" Jackson was a U.S. Congressman and Senator from the state of Washington from 1941 until his death...

of Washington stated that he was "at a loss" to see how the bill affected religion, as its opponents said. Senator Alan Bible

Alan Bible

Alan Harvey Bible was a Nevada politician of the Democratic Party who served as a United States Senator from 1954 until 1974.-Biography:...

of Nevada

Nevada

Nevada is a state in the western, mountain west, and southwestern regions of the United States. With an area of and a population of about 2.7 million, it is the 7th-largest and 35th-most populous state. Over two-thirds of Nevada's people live in the Las Vegas metropolitan area, which contains its...

, the acting chairman of the Subcommittee on Territories and Insular Affairs, told the bill's opponents that nothing in the proposed legislation would permit the removal of any non-Alaskan to the territory for confinement.

Republican Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

proposed an amended bill that removed the commitment procedures in title I of the House bill and stated that "Nothing in this title shall be construed to authorize the transfer to Alaska, pursuant to any agreement or otherwise, of any mentally ill person who is not a resident of Alaska." In effect, this eliminated the bill's most controversial element—the provision for the transfer of mental patients from the lower 48 states to Alaska. The final recommendation of the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs followed Goldwater's lead that the bill be amended to strike all the controversial "detailed provisions for commitment, hospitalization, and care of the mentally ill of Alaska" included in title I of the original House bill. This amended proposal left only the transfer of responsibility for mental health care to the territory of Alaska and the establishment of land grants to support this care. The committee stressed that they were not invalidating the title I provisions of the original bill but that they had been misunderstood, a recurrent theme in supporters of the bill:

However, the proposed provisions were misunderstood by many persons in parts of the country other than Alaska. Partly as a result of this misunderstanding, but more because the members of the committee are convinced that the people of Alaska are fully capable of drafting their own laws for a mental health program for Alaska, the committee concluded that authority should be vested in them in this field comparable to that of the States and other Territories.

Thus amended, the Senate bill (S. 2973) was passed unanimously by the Senate on July 20, after only ten minutes of debate.

Aftermath

Following the passage of the act, an Alaska Mental Health Trust was set up to administer the land and grants appropriated to fund the Alaskan mental health program. During the 1970s, the issue of the trust's land became increasingly controversial, with the state coming under increasing pressure to develop the land for private and recreational use. In 1978, the Alaska LegislatureAlaska Legislature

The Alaska Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is a bicameral institution, consisting of the lower Alaska House of Representatives, with 40 members, and the upper house Alaska Senate, with 20 members...

passed a law to abolish the trust and transfer the most valuable parcels of lands to private individuals and the government. By 1982, 40000 acres (161.9 km²) had been conveyed to municipalities, 50000 acres (202.3 km²) transferred to individuals, and slightly over 350000 acres (1,416.4 km²) designated as forests, parks or wildlife areas. Around 35 percent of the land trust remained unencumbered and in state ownership.

The loss of the land and the revenue earned from it had a severe effect on mental health care in the state. In 1982, Alaska resident Vern Weiss filed a lawsuit on behalf of his son, who required mental health services that were not available in Alaska. The case of Weiss v State of Alaska eventually became a class action

Class action

In law, a class action, a class suit, or a representative action is a form of lawsuit in which a large group of people collectively bring a claim to court and/or in which a class of defendants is being sued...

lawsuit involving a range of mental health care groups. The Alaska Supreme Court

Alaska Supreme Court

The Alaska Supreme Court is the state supreme court in the State of Alaska's judicial department . The supreme court is composed of the chief justice and four associate justices, who are all appointed by the governor of Alaska and face judicial retention elections and who choose one of their own...

ruled in 1985 that the abolition of the trust had been illegal and ordered it to be reconstituted. However, as much of the original land had been transferred away, the parties had to undergo a long and complex series of negotiations to resolve the situation. A final settlement was reached in 1994 in which the trust was reconstituted with 500000 acres (2,023.4 km²) of original trust land, 500000 acres (2,023.4 km²) of replacement land, and $200 million to replace lost income and assets.

Scientology and the Alaska Mental Health Bill

The Alaska Mental Health Bill plays a major part in the Church of Scientology's account of its campaign against psychiatry. The Church participated in the campaign against the Bill and still refers to it as the "Siberia Bill". Scientology may also have provided an important piece of the "evidence" which the anti-bill campaigners used — a booklet titled Brain-Washing: A Synthesis of the Russian Textbook on Psychopolitics, which has been widely attributed to the anonymous authorship of L. Ron Hubbard (see Brainwashing Manual).Scientology position

The church's official website asserts that the bill was "psychiatry's attempt to establish a million-acre (4,000 km²) Siberia-type camp for mental health patients in Alaska, far from the prying eyes of civil libertarians" which "presumably ... was far enough away from the well-traveled roads of the world to allow psychiatrists to conduct their mind control and other experiments on a captive population, unhindered by the glare of publicity." It would give psychiatrists the power to ensure that "Any man, woman or child could be seized and sent without trial to Alaska, deprived of human and civil rights and detained forever, all without trial or examination." According to the Church's Freedom MagazineFreedom Magazine

Freedom Magazine is a magazine published by the Church of Scientology since 1968. The magazine describes its focus as "Investigative Reporting in the Public Interest." A frequent topic is psychiatry .-Content:...

:

Church officials have stated their belief that the American Psychiatric Association intensified its "interest in destroying Dianetics

Dianetics

Dianetics is a set of ideas and practices regarding the metaphysical relationship between the mind and body that was invented by the science fiction author L. Ron Hubbard and is practiced by followers of Scientology...

and Scientology organizations ... when the Church of Scientology actively opposed a bill whose introduction in Congress had been secure by the APA. ... The APA was well aware of who was behind the massive response that defeated the legislation, and they never forgot, as can be seen from some of the attacks its members generated."

Miscavige on Nightline

Similarly, David MiscavigeDavid Miscavige

David Miscavige is the leader of the Church of Scientology and affiliated organizations. His title is Chairman of the Board of Religious Technology Center , a corporation that controls the trademarked names and symbols of Dianetics and Scientology. Miscavige was an assistant to Hubbard while a...

, the church's leader, in 1992 told Ted Koppel

Ted Koppel

Edward James "Ted" Koppel is an English-born American broadcast journalist, best known as the anchor for Nightline from the program's inception in 1980 until his retirement in late 2005. After leaving Nightline, Koppel worked as managing editor for the Discovery Channel before resigning in 2008...

in an interview on the Nightline program:

Conspiracy theories

In Ron's Journal 67, Hubbard identified "the people behind the Siberia Bill", who he asserted were- less than twelve men. They are members of the Bank of England and other higher financial circles. They own and control newspaper chains, and they are, oddly enough, directors in all the mental health groups in the world which have sprung up. Now these chaps are very interesting fellows: They have fantastically corrupt backgrounds; illegitimate children; government graft; a very unsavory lot. And they apparently, sometime in the rather distant past, had determined on a course of action. Being in control of most of the gold supplies of the planet, they entered upon a program of bringing every government to bankruptcy and under their thumb, so that no government would be able to act politically without their permission.

According to David Miscavige, the bill was the product of a conspiracy by the American Psychiatric Association. In a public address in 1995, he told Scientologists that it was "in 1955 that the agents for the American Psychiatric Association met on Capitol Hill to ram home the infamous Siberia Bill, calling for a secret concentration camp in the wastes of Alaska." It was "here that Mr. Hubbard, as the leader of a new and dynamic religious movement, knocked that Siberia Bill right out of the ring — inflicting a blow they would never forget." The assertion that Scientologists defeated the bill is made frequently in Scientology literature. In fact, the original version of the bill with the offending Title I commitment provisions only passed the House of Representatives; it was subsequently amended in conference to strike the commitment portion and retain the transfer of responsibility for mental health care. The revised bill passed easily without further changes.

Contemporary publications

Contemporary Church publications suggest that although Hubbard was tracking progress of the bill at least as early as February 1956, Scientology did not become involved in the controversy until the start of March 1956, over two months after the American Public Relations Forum had first publicized the bill. A March "Professional Auditor's Bulletin" issued by Hubbard, who was staying in Dublin at the time, includes a telegram from his Washington-based son L. Ron Hubbard, Jr.Ronald DeWolf

Ronald Edward DeWolf , born Lafayette Ronald Hubbard, Jr., also known as "Nibs" Hubbard, was the eldest child of Scientology founder L...

and two other Scientologists alerting him to the upcoming February Senate hearings:

HOUSE BILL 6376 PASSED JANUARY 18TH STOP GOES SENATE NEXT WEEK STOP BILL PERMITS ADMISSION OF PERSON TO MENTAL INSTITUTION BY WRITTEN APPLICATION OF INTERESTED PERSON BEFORE JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS ARE HELD STOP DISPENSES WITH REQUIREMENT THAT PATIENT BE PRESENT AT HEARING STOP ANYONE CAN BE EXCLUDED FROM HEARING STOP BILL PERTAINS TO ALASKA AT MOMENT STOP BILL SETS UP ONE MILLION ACRES SIBERIAL IN ALASKA FOR INSTITUTIONS STOP LETTER AND BILL FOLLOW STOP WHAT ACTION YOU WANT TAKEN.

Although the church says that Scientologists led the opposition to the bill, the Congressional Record

Congressional Record

The Congressional Record is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress. It is published by the United States Government Printing Office, and is issued daily when the United States Congress is in session. Indexes are issued approximately every two weeks...

s account of the Senate hearings into the bill does not mention the church. A contemporary review of the opposition to the bill likewise attributes the lead role elsewhere and to right-wing groups, rather than the "civil liberties" organizations cited by the church:

Only a few organized groups got behind the hue and cry. Most influential was the libertarian Association of Physicians and Surgeons, and Dan Smoot's newsletter. Right-wing groups bombarded Congress with protests and demands for hearings.

See also

- Citizens Commission on Human RightsCitizens Commission on Human RightsThe Citizens Commission on Human Rights is an advocacy group established in 1969 by the Church of Scientology and psychiatrist Thomas Szasz. The group promotes several video campaigns which support views against psychiatry...

- Scientology and psychiatryScientology and psychiatryScientology and psychiatry have come into conflict since the foundation of Scientology in 1952. Scientology is publicly, and often vehemently, opposed to both psychiatry and psychology. Scientologists view psychiatry as a barbaric and corrupt profession and encourage alternative care based on...

- Scientology controversies

- Water fluoridation controversyWater fluoridation controversyThe water fluoridation controversy arises from moral, ethical, and safety concerns regarding the fluoridation of public water supplies. The controversy occurs mainly in English-speaking countries, as Continental Europe does not practice water fluoridation...

External links

- Alaska Mental Health Trust Authority

- Mental Health Trust Land Office

- Nightline: A Conversation with David Miscavige, February 14, 1992, interviewed by Ted Koppel - Miscavige discussing the Church of Scientology's view of the Act.