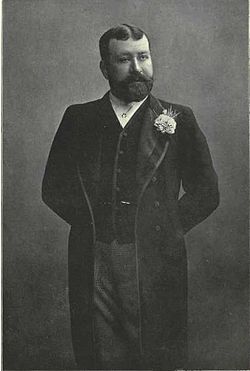

Montague Druitt

Encyclopedia

Montague John Druitt was one of the suspects in the Jack the Ripper

murders that took place in London between August and November 1888.

He came from an upper-middle class English background, and studied at Winchester College

and the University of Oxford. After graduating, he took a position at a boarding school

and pursued a parallel career in the law; he qualified as a barrister

in 1885. His main interest outside work was cricket, which he played with many leading players of the time, including Lord Harris

and Francis Lacey

.

In November 1888, he lost his post at the school for reasons that remain unclear. One month later his body was found drowned in the River Thames

. His death, which was found to be a suicide, roughly coincided with the end of the murders that were attributed to Jack the Ripper. Private suggestions in the 1890s that he could have committed the crimes became public knowledge in the 1960s, and led to the publication of books that proposed him as the murderer. The evidence against him was entirely circumstantial

, however, and many writers from the 1970s onwards have rejected him as a likely suspect.

, Dorset, England. He was the second son and third child of prominent local surgeon William Druitt, and his wife Ann (née Harvey). William Druitt was a Justice of the Peace

, a governor of the local grammar school

, and a regular worshiper at the local Anglican

church, the Minster. Montague was christened at the Minster by his maternal great-uncle, Rev. William Mayo, six weeks after his birth. The Druitts lived at Westfield House, which was the largest house in the town and set in its own grounds with stables and servants' cottages. The house still stands in Wimborne Minster at the end of Westfield Close and is now subdivided into flats. Montague had six brothers and sisters, including an elder brother William who entered the law, and a younger brother Edward who joined the Royal Engineers

.

Montague was educated at Winchester College, where he won a scholarship at the age of 13, and excelled at sports, especially cricket

and fives

. He was active in the school's debating society, an interest that might have spawned his desire to become a barrister. He spoke in favour of French republicanism

, compulsory military service, and the resignation of Benjamin Disraeli, and against the Ottoman Empire

, the influence of Otto von Bismarck

, and the conduct of the government in the Tichbourne case. He defended William Wordsworth

as "a bulwark of Protestantism", and condemned the execution of King Charles I

as "a most dastardly murder that will always attach to England's fair name as a blot". In a light-hearted debate, he spoke against the proposition that bondage to fashion is a social evil. In his final year at Winchester, 1875–76, he was Prefect of Chapel, treasurer of the debating society, school fives champion, and opening bowler for the cricket team. In June 1876, he played cricket against Eton College

, whose winning team included cricketing luminaries Ivo Bligh

and Kynaston Studd

, and future Principal Private Secretary

at the Home Office

Evelyn Ruggles-Brise

. Druitt bowled out Studd for four. With a glowing academic record, he was awarded a Winchester Scholarship to New College, Oxford

.

At New College, he was popular with his peers, and was elected Steward of the Junior Common Room by his fellow students. He played cricket and rugby for the college team, and was the winner of both double and single fives at the university in 1877. In a seniors' cricket match in 1880, he bowled out William Patterson

, who later captained Kent County Cricket Club

. Druitt graduated from Oxford in 1880 with a third class Bachelor of Arts degree in Classics. Montague's youngest brother, Arthur, entered New College in 1882, just as Montague followed in his eldest brother William's footsteps by embarking on a career in the law.

, one of the qualifying bodies for English barrister

s. His father had promised him a legacy of £500 (equivalent to £ today), and Druitt paid his membership fees with a loan from his father secured against the inheritance. He was called to the bar

on 29 April 1885, and set up a practice as a barrister and special pleader

. Druitt's father died suddenly from a heart attack in September 1885, leaving an estate valued at £16,579 (equivalent to £ today). In a codicil

, Druitt senior instructed his executors to deduct the money he had advanced to his son from the legacy of £500. Montague received very little money, if any, from his father's will, although he did receive some of his father's personal possessions. Most of Dr Druitt's estate went to his wife Ann, three unmarried daughters (Georgiana, Edith and Ethel), and eldest son William.

Druitt rented legal chambers at 9 King's Bench Walk in the Inner Temple. In the late Victorian era

only the wealthy could afford legal action, and only one in eight qualified barristers was able to make a living from the law. While some of Druitt's biographers claim his practice did not flourish, others suppose that it provided him with a relatively substantial income on the basis of his costly lease of chambers and the value of his estate at death. He is listed in the Law List of 1886 as active in the Western Circuit and Winchester

Sessions

, and for 1887 in the Western Circuit and Hampshire

, Portsmouth

and Southampton

Assizes

.

To supplement his income and help pay for his legal training, Druitt worked as an assistant schoolmaster at George Valentine's boarding school

, 9 Eliot Place, Blackheath, London

, from 1880. The school had a long and distinguished history; Benjamin Disraeli had been a pupil there in the 1810s, and boys from the school had been playmates of a younger son of Queen Victoria

, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, who as a boy in the 1860s had lived nearby at Greenwich Park

. Druitt's post came with accommodation in Eliot Place, and the long school holidays gave him time to study the law and to pursue his interest in cricket.

. He was particularly noted for his skill as a bowler. In 1882 and 1883, he toured the West Country

with a gentleman's touring team called the Incogniti

. One of Druitt's fellow local players was Francis Lacey

, the first man knighted for services to cricket. Druitt played for another wandering team, the Butterflies, on 14 June 1883, when they drew against his alma mater Winchester College. The team included first-class cricketers A. J. Webbe, J. G. Crowdy

, John Frederick

and Charles Seymour

.

While working at Blackheath, Druitt joined the local cricket club, Blackheath Morden, and became the club's treasurer. It was a well-connected club: the President was politician Sir Charles Mills

and one of its players was Stanley Christopherson

. After the merger of the club with other local sports associations to form the Blackheath Cricket, Football and Lawn Tennis Company

, Druitt took on the additional roles of company secretary and director. The inaugural game of the new club was played against George Gibbons Hearne

's Eleven, which included many members of the famous cricketing Hearne family

. Hearne's team won by 21 runs. On 5 June 1886, in a match between Blackheath and a gentleman's touring team called the Band of Brothers, led by Lord Harris

, Druitt bowled Harris for 14 and took three other wickets. Blackheath won by 178 runs. Two weeks later, he dismissed England batsman John Shuter

, who was playing for Bexley Cricket Club

, for a duck

, and Blackheath won the game by 114 runs. The following year, Shuter returned to Blackheath with a Surrey County side

that included Walter Read

, William Lockwood

, and Bobby Abel

, whom Druitt bowled out for 56. Surrey won by 147 runs.

On 26 May 1884, Druitt was elected to the Marylebone Cricket Club

(MCC) on the recommendation of his fellow Butterflies player Charles Seymour, who proposed him, and noted fielder Vernon Royle

, who seconded his nomination. One of the minor matches he played for MCC was with England bowler William Attewell

against Harrow School

on 10 June 1886. MCC won by 57 runs. He also played against MCC for Blackheath: on 23 July 1887, he bowled out Dick Pougher

for 28 runs, but Druitt only made 5 runs before he was bowled out by Arnold Fothergill

with a ball caught by Pougher. MCC won by 52 runs.

In June 1888, Lord Harris played twice for Blackheath with Druitt and Stanley Christopherson; Blackheath won both matches easily, but Druitt was off form and contributed neither runs nor wickets in either match. In August 1888, Druitt played for the Gentlemen of Bournemouth

against the Parsees cricket team

during their tour of England

, and took five wickets in the visitors' first innings. Nevertheless, the Parsees won. On 8 September 1888, the Blackheath Club played against the Christopherson brothers. Druitt was bowled out by Stanley Christopherson, who was playing with his brothers instead of for Blackheath, and in reply Druitt bowled out Christopherson. Blackheath won by 22 runs.

In addition to cricket, Druitt also participated in field hockey.

On 31 December 1888, his body was found floating in the River Thames

, off Thornycroft's

torpedo works, Chiswick

, by a waterman named Henry Winslade. Stones in Druitt's pockets had kept his body submerged for about a month. He was carrying a train ticket to Hammersmith dated 1 December, a silver watch, a cheque for £50 and £16 in gold (equivalent to £ and £ today). It is not known why he should have carried such a large amount of money, but it could have been a final payment from the school.

Some modern authors suggest that Druitt was dismissed because he was a homosexual or pederast and that it may have driven him to suicide. One speculation is that the money found on his body was going to be used for payment to a blackmailer. Others, however, think that there is no evidence of homosexuality and that his suicide was instead precipitated by an hereditary psychiatric illness. His mother suffered from depression and was institutionalised from July 1888. She died in an asylum in Chiswick in 1890. His maternal grandmother committed suicide while insane; his aunt attempted suicide; and his eldest sister committed suicide in old age. A note written by Druitt and addressed to his brother William, who was a solicitor in Bournemouth, was found in Druitt's room in Blackheath. It read, "Since Friday I felt that I was going to be like mother, and the best thing for me was to die."

As was usual in the district, the inquest was held at the Lamb Tap public house

, Chiswick, by the coroner Dr Thomas Bramah Diplock on 2 January 1889. The coroner's jury concluded that Druitt had committed suicide by drowning while in an unsound state of mind. He was buried in Wimborne cemetery the next day. At probate, his estate was valued at £2,600 (equivalent to £ today).

It is not known why Druitt committed suicide in Chiswick. One suggested link is that one of his University friends, Thomas Seymour Tuke of the Tuke family

, lived there. Tuke was a psychiatric doctor with whom Druitt played cricket, and Druitt's mother was committed to Tuke's asylum in 1890. Another suggestion is that Druitt knew Harry Wilson, whose house, "The Osiers", lay between Hammersmith station and Thornycroft's wharf, where Druitt's body was found.

On 31 August 1888, Mary Ann Nichols

On 31 August 1888, Mary Ann Nichols

was found murdered in the impoverished Whitechapel

district in the East End of London

. Her throat was slashed. During September, three more women (Annie Chapman

on the 8th and Elizabeth Stride

and Catherine Eddowes

on the 30th) were found dead with their throats cut. On 9 November 1888, the body of Mary Jane Kelly

was discovered. Her throat had been severed down to the spine. In four of the cases the bodies were mutilated after death. The similarities between the crimes led to the supposition that they were committed by the same assailant, who was given the nickname "Jack the Ripper

". Despite an extensive police investigation into the five murders, the Ripper was never identified and the crimes remained unsolved.

Shortly after Kelly's murder, stories that the Ripper had drowned in the Thames began to circulate. In February 1891, the MP for West Dorset, Henry Richard Farquharson

, announced that Jack the Ripper was "the son of a surgeon" who had committed suicide on the night of the last murder. Although Farquharson did not name his suspect, the description resembles Druitt. Farquharson lived 10 miles (16 km) from the Druitt family and was part of the same social class. The Victorian journalist George R. Sims noted in his memoirs, The Mysteries of Modern London (1906), "[the Ripper's] body was found in the Thames after it had been in the river for about a month". Similar comments were made by Sir John Moylan, Assistant Under-Secretary of the Home Office: "[the Ripper] escaped justice by committing suicide at the end of 1888" and Sir Basil Thomson

, made Assistant Commissioner of the CID in 1913: "[the Ripper was] an insane Russian doctor [who] escaped arrest by committing suicide in the Thames at the end of 1888". Neither Moylan nor Thomson was involved in the investigation.

Assistant Chief Constable

Sir Melville Macnaghten

named Druitt as a suspect in the case in a private handwritten memorandum of 23 February 1894. Macnaghten highlighted the coincidence between Druitt's disappearance and death shortly after the last of the five murders on 9 November 1888, and claimed to have unspecified "private information" that left "little doubt" Druitt's own family believed him to have been the murderer. Macnaghten's memo was eventually discovered in his personal papers by his daughter, Lady Aberconway, who showed them to British broadcaster Dan Farson. A slightly different abridged copy of the memo found in the Metropolitan Police archive was released to the public in 1966. Farson first revealed Druitt's initials "MJD" in a television programme in November 1959. In 1961, Farson investigated a claim by an Australian that Montague's cousin, Lionel Druitt, had written a pamphlet that claimed knowledge of the Ripper's identity, but the claim was never substantiated. Journalist Tom Cullen revealed Druitt's full name in his 1965 book Autumn of Terror, which was followed by Farson's 1972 book Jack the Ripper. Before the discovery of Macnaghten's memo, books on the Ripper case, such as those written by Leonard Matters

and Donald McCormick

, poured scorn on stories that the Ripper had drowned in the Thames because they could not find a suicide that matched the description of the culprit. Cullen and Farson, however, supposed that Druitt was the Ripper on the basis of the Macnaghten memorandum, the near coincidence between Druitt's death and the end of the murders, the closeness of Whitechapel to Druitt's rooms in the Inner Temple, the insanity that was acknowledged by the inquest verdict of "unsound mind", and the possibility that Druitt had absorbed the rudimentary anatomical skill supposedly shown by the Ripper through observing his father at work.

Since the publication of Cullen's and Farson's books, other Ripper authors have argued that their theories are based solely on flawed circumstantial evidence, and have attempted to provide Druitt with alibis for the times of the murders. On 1 September, the day after the murder of Nichols, Druitt was in Dorset playing cricket. On the day of Chapman's murder, he played cricket in Blackheath, and the day after the murders of Stride and Eddowes, he was in the West Country defending a client in a court case. While writers Andrew Spallek and Tom Cullen argue that Druitt had the time and opportunity to travel by train between London and his cricket and legal engagements, or use his city chambers as a base from which to commit the murders, others dismiss the possibility as "improbable". Many experts believe that the killer was local to Whitechapel, whereas Druitt lived miles away on the other side of the River Thames. His chambers were within walking distance of Whitechapel, and his regular rail commute would almost certainly have brought him to Cannon Street station

, a few minutes' walk from the East End. It seems unlikely, however, that he could have travelled the distance in blood-stained clothes unnoticed, and a clue discovered during the investigation into the murder of Catherine Eddowes (a piece of her blood-stained clothing

) indicates that the murderer travelled north-east from where she was murdered, but Druitt's chambers and the railway station were south-westwards.

Macnaghten incorrectly described Druitt as a 41-year-old doctor, and cited allegations that he "was sexually insane" without specifying the source or details of the allegations. Macnaghten did not join the force until 1889, after the murder of Kelly and the death of Druitt, and was not involved in the investigation directly. Macnaghten's memorandum named two other suspects ("Kosminski"

and Michael Ostrog) and was written to refute allegations against a fourth, Thomas Cutbush. The three Macnaghten suspects—Druitt, Kosminski and Ostrog—also match the descriptions of three unnamed suspects in Major Arthur Griffiths' Mysteries of Police and Crime (1898); Griffiths was Inspector of Prisons at the time of the Ripper murders. Inspector Frederick Abberline

, who was the lead investigative officer in the case, appeared to dismiss Druitt as a suspect on the basis that the only evidence against him was the coincidental timing of his suicide shortly after the fifth murder. Other officials involved in the Ripper case, Metropolitan Police Commissioner

James Monro

and pathologist Thomas Bond

, believed that the murder of Alice McKenzie on 17 July 1889, seven months after Druitt's death, was committed by the same culprit as the earlier murders. The inclusion of McKenzie among the Ripper's victims was contested by Abberline and Macnaghten among others, but if she was one of his victims, then Druitt clearly could not be the Ripper. Another murder occasionally included among the Ripper cases is that of Martha Tabram

, who was viciously stabbed to death on 7 August 1888. Her death coincided with the middle of Bournemouth Cricket Week, 4–11 August, in which Druitt was heavily involved, and was in the school holiday, which Druitt spent in Dorset. In the words of one of his biographers, "It scarcely left time for a 200-mile round dash to fit in a murder."

and Freemasonry

. The theories are widely condemned as ridiculous, and implicate Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, his tutor James Stephen

, and their doctor Sir William Gull to varying degrees. One version of the conspiracy promoted by Stephen Knight in his 1976 book Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution supposed that Druitt was a scapegoat, chosen by officialdom to take the blame for the murders. Martin Howells and Keith Skinner followed the same line in their 1987 book The Ripper Legacy, which was panned by one critic as being based on "no evidence whatever".

The theories attempted to link Druitt with Clarence, Gull and Stephen through a network of mutual acquaintances and possible connections. Reginald Acland

, the brother of Gull's son-in-law, had legal chambers in King's Bench Walk near Druitt's, as did Harry Stephen, who was James Stephen's brother. Harry Stephen was good friends with Harry Wilson, who had a house in Chiswick, "The Osiers", near to where Druitt's body was found. Wilson and James Stephen were close friends of Clarence, and were both members of an exclusive society called the Cambridge Apostles

. As a schoolboy, Druitt had played cricket against two of Wilson's friends, Kynaston Studd

and Henry Goodhart, who was also one of the Apostles. Another potential connection between Druitt and Wilson is through John Henry Lonsdale. Lonsdale's name and Blackheath address are written in a diary belonging to Wilson now in the possession of Trinity College, Cambridge

. Lonsdale's address is a few yards from the school at which Druitt worked and lived, and Lonsdale had been a barrister and had also rented legal chambers in King's Bench Walk. In 1887, Lonsdale entered the church and was assigned as curate to Wimborne Minster, where the Druitt family worshiped. Lonsdale and Macnaghten were classmates at Eton

, and so theorists argue that Lonsdale might have been in a position to provide "private information" to Macnaghten regarding Druitt. The connections between the Apostles and Druitt led to the suggestion that he was part of the same social set. Druitt, his mother and his sister Georgiana were invited to a ball in honour of Clarence at the home of Lord Wimborne on 17 December 1888, although they did not attend because by that time Montague was dead, his mother was in an asylum, and his sister was expecting her second child. Clarence, Stephen, Wilson, Studd, and Goodhart are suggested to have been homosexual, although this is contested by historians. John Wilding's 1993 book Jack the Ripper Revealed used the connections between Druitt and Stephen to propose that they committed the crimes together, but reviewers considered it an "imaginative tale ... most questionable", an "exercise in ingenuity rather than ... fact", and "lack[ing] evidential support".

In his 2005 and 2006 biographies of Druitt, D. J. Leighton concluded that Druitt was innocent, but repeated some of Knight's and Wilding's discredited claims. Leighton suggested that Druitt could have been murdered either out of greed by his elder brother William or, as previously suggested by Howells and Skinner, out of fear of exposure by Harry Wilson's homosexual cronies. The propensity of theorists to associate Ripper suspects with homosexuality has led scholars to assume that such notions are based on homophobia

rather than evidence.

The accusations against Clarence, Stephen, Gull and Druitt also draw on cultural perceptions of a decadent aristocracy, and depict an upper-class murderer or murderers preying on lower-class victims. As Druitt and the other aristocratic Ripper suspects were wealthy, there is more biographical material on them than on the residents of the Whitechapel

slums. Consequently, it is easier for writers to construct solutions based on a wealthy culprit rather than one based on a Whitechapel resident. There is no direct evidence against Druitt, and since the 1970s, the number of Jack the Ripper suspects has continued to grow, with the result that there are now over 100 different theories about the Ripper's identity.

story The Revenge of Moriarty, Professor Moriarty

's criminal exploits are hampered by increased police activity as a result of the Jack the Ripper murders. He discovers that Druitt is the murderer and so fakes his suicide in the hope that the police will lose interest once the murders cease. The TV series Sanctuary depicts John Druitt as a scientist with the ability to teleport. Druitt is inhabited by an evil energy being, goes mad and becomes Jack the Ripper. His ability to teleport explains how he committed the murders when historical records show him distant from the crime scenes. In the anime Kuroshitsuji, the Viscount of Druitt is a suspect in the murders of several prostitutes, also dubbed the "Jack the Ripper" case. In Alan Moore

and Eddie Campbell

's graphic novel From Hell

, which was based on Stephen Knight's book, Druitt is portrayed as a feminist with a deep love of cricket who is framed by the Freemasons as being a paedophile and misogynist; the Freemasons plant "clues" that he is Jack the Ripper and kill him, faking it as suicide, to ensure that he is not tried.

Jack the Ripper

"Jack the Ripper" is the best-known name given to an unidentified serial killer who was active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. The name originated in a letter, written by someone claiming to be the murderer, that was disseminated in the...

murders that took place in London between August and November 1888.

He came from an upper-middle class English background, and studied at Winchester College

Winchester College

Winchester College is an independent school for boys in the British public school tradition, situated in Winchester, Hampshire, the former capital of England. It has existed in its present location for over 600 years and claims the longest unbroken history of any school in England...

and the University of Oxford. After graduating, he took a position at a boarding school

Boarding school

A boarding school is a school where some or all pupils study and live during the school year with their fellow students and possibly teachers and/or administrators. The word 'boarding' is used in the sense of "bed and board," i.e., lodging and meals...

and pursued a parallel career in the law; he qualified as a barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

in 1885. His main interest outside work was cricket, which he played with many leading players of the time, including Lord Harris

George Harris, 4th Baron Harris

George Robert Canning Harris, 4th Baron Harris, GCSI, GCIE was a British politician, cricketer and cricket administrator...

and Francis Lacey

Francis Lacey

Sir Francis Eden Lacey was the first man to be knighted for services to cricket, on retiring as Secretary of MCC, a post which he held from 1898 to 1926. As Secretary, he initiated many important reforms...

.

In November 1888, he lost his post at the school for reasons that remain unclear. One month later his body was found drowned in the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

. His death, which was found to be a suicide, roughly coincided with the end of the murders that were attributed to Jack the Ripper. Private suggestions in the 1890s that he could have committed the crimes became public knowledge in the 1960s, and led to the publication of books that proposed him as the murderer. The evidence against him was entirely circumstantial

Circumstantial evidence

Circumstantial evidence is evidence in which an inference is required to connect it to a conclusion of fact, like a fingerprint at the scene of a crime...

, however, and many writers from the 1970s onwards have rejected him as a likely suspect.

Early life

Druitt was born in Wimborne MinsterWimborne Minster

Wimborne Minster is a market town in the East Dorset district of Dorset in South West England, and the name of the Church of England church in that town...

, Dorset, England. He was the second son and third child of prominent local surgeon William Druitt, and his wife Ann (née Harvey). William Druitt was a Justice of the Peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

, a governor of the local grammar school

Queen Elizabeth's School, Wimborne Minster

Queen Elizabeth's School is a co-educational voluntary controlled Church of England secondary school in Wimborne Minster, Dorset, England.-Admissions:...

, and a regular worshiper at the local Anglican

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

church, the Minster. Montague was christened at the Minster by his maternal great-uncle, Rev. William Mayo, six weeks after his birth. The Druitts lived at Westfield House, which was the largest house in the town and set in its own grounds with stables and servants' cottages. The house still stands in Wimborne Minster at the end of Westfield Close and is now subdivided into flats. Montague had six brothers and sisters, including an elder brother William who entered the law, and a younger brother Edward who joined the Royal Engineers

Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually just called the Royal Engineers , and commonly known as the Sappers, is one of the corps of the British Army....

.

Montague was educated at Winchester College, where he won a scholarship at the age of 13, and excelled at sports, especially cricket

Cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of 11 players on an oval-shaped field, at the centre of which is a rectangular 22-yard long pitch. One team bats, trying to score as many runs as possible while the other team bowls and fields, trying to dismiss the batsmen and thus limit the...

and fives

Fives

Fives is a British sport believed to derive from the same origins as many racquet sports. In fives, a ball is propelled against the walls of a special court using gloved or bare hands as though they were a racquet.-Background:...

. He was active in the school's debating society, an interest that might have spawned his desire to become a barrister. He spoke in favour of French republicanism

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

, compulsory military service, and the resignation of Benjamin Disraeli, and against the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, the influence of Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck

Otto Eduard Leopold, Prince of Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg , simply known as Otto von Bismarck, was a Prussian-German statesman whose actions unified Germany, made it a major player in world affairs, and created a balance of power that kept Europe at peace after 1871.As Minister President of...

, and the conduct of the government in the Tichbourne case. He defended William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth was a major English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with the 1798 joint publication Lyrical Ballads....

as "a bulwark of Protestantism", and condemned the execution of King Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

as "a most dastardly murder that will always attach to England's fair name as a blot". In a light-hearted debate, he spoke against the proposition that bondage to fashion is a social evil. In his final year at Winchester, 1875–76, he was Prefect of Chapel, treasurer of the debating society, school fives champion, and opening bowler for the cricket team. In June 1876, he played cricket against Eton College

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

, whose winning team included cricketing luminaries Ivo Bligh

Ivo Bligh, 8th Earl of Darnley

Ivo Francis Walter Bligh, 8th Earl of Darnley DL, JP , styled The Honourable Ivo Bligh until 1900, was a British cricketer who captained the English team in the first ever Test series against Australia with the Ashes at stake in 1882/83...

and Kynaston Studd

Kynaston Studd

Sir John Edward Kynaston Studd, 1st Baronet OBE , known as "JEK", was a British cricketer, businessman and Lord Mayor of London.-Family:...

, and future Principal Private Secretary

Principal Private Secretary

In the British Civil Service and Australian Public Service the Principal Private Secretary is the civil servant who runs a cabinet minister's private office...

at the Home Office

Home Office

The Home Office is the United Kingdom government department responsible for immigration control, security, and order. As such it is responsible for the police, UK Border Agency, and the Security Service . It is also in charge of government policy on security-related issues such as drugs,...

Evelyn Ruggles-Brise

Evelyn Ruggles-Brise

Sir Evelyn John Ruggles-Brise KCB was a British prison administrator and reformer, and founder of the Borstal system.-Biography:...

. Druitt bowled out Studd for four. With a glowing academic record, he was awarded a Winchester Scholarship to New College, Oxford

New College, Oxford

New College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.- Overview :The College's official name, College of St Mary, is the same as that of the older Oriel College; hence, it has been referred to as the "New College of St Mary", and is now almost always...

.

At New College, he was popular with his peers, and was elected Steward of the Junior Common Room by his fellow students. He played cricket and rugby for the college team, and was the winner of both double and single fives at the university in 1877. In a seniors' cricket match in 1880, he bowled out William Patterson

William Patterson (cricketer)

William Harry Patterson was an English amateur cricketer during the latter part of the 19th century. A right-handed batsman who occasionally bowled, he was the joint captain of Kent County Cricket Club between 1890 and 1893....

, who later captained Kent County Cricket Club

Kent County Cricket Club

Kent County Cricket Club is one of the 18 first class county county cricket clubs which make up the English and Welsh national cricket structure, representing the county of Kent...

. Druitt graduated from Oxford in 1880 with a third class Bachelor of Arts degree in Classics. Montague's youngest brother, Arthur, entered New College in 1882, just as Montague followed in his eldest brother William's footsteps by embarking on a career in the law.

Career

On 17 May 1882, two years after graduation, Druitt was admitted to the Inner TempleInner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court in London. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, an individual must belong to one of these Inns...

, one of the qualifying bodies for English barrister

Barrister

A barrister is a member of one of the two classes of lawyer found in many common law jurisdictions with split legal professions. Barristers specialise in courtroom advocacy, drafting legal pleadings and giving expert legal opinions...

s. His father had promised him a legacy of £500 (equivalent to £ today), and Druitt paid his membership fees with a loan from his father secured against the inheritance. He was called to the bar

Bar (law)

Bar in a legal context has three possible meanings: the division of a courtroom between its working and public areas; the process of qualifying to practice law; and the legal profession.-Courtroom division:...

on 29 April 1885, and set up a practice as a barrister and special pleader

Special pleader

A special pleader was a historial legal occupation. The practitioner, or "special pleader" in English law specialised in drafting "pleadings", in modern terminology statements of case.-History:...

. Druitt's father died suddenly from a heart attack in September 1885, leaving an estate valued at £16,579 (equivalent to £ today). In a codicil

Codicil (will)

A codicil is a document that amends, rather than replaces, a previously executed will. Amendments made by a codicil may add or revoke small provisions , or may completely change the majority, or all, of the gifts under the will...

, Druitt senior instructed his executors to deduct the money he had advanced to his son from the legacy of £500. Montague received very little money, if any, from his father's will, although he did receive some of his father's personal possessions. Most of Dr Druitt's estate went to his wife Ann, three unmarried daughters (Georgiana, Edith and Ethel), and eldest son William.

Druitt rented legal chambers at 9 King's Bench Walk in the Inner Temple. In the late Victorian era

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

only the wealthy could afford legal action, and only one in eight qualified barristers was able to make a living from the law. While some of Druitt's biographers claim his practice did not flourish, others suppose that it provided him with a relatively substantial income on the basis of his costly lease of chambers and the value of his estate at death. He is listed in the Law List of 1886 as active in the Western Circuit and Winchester

Winchester

Winchester is a historic cathedral city and former capital city of England. It is the county town of Hampshire, in South East England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, and is located at the western end of the South Downs, along the course of...

Sessions

Quarter Sessions

The Courts of Quarter Sessions or Quarter Sessions were local courts traditionally held at four set times each year in the United Kingdom and other countries in the former British Empire...

, and for 1887 in the Western Circuit and Hampshire

Hampshire

Hampshire is a county on the southern coast of England in the United Kingdom. The county town of Hampshire is Winchester, a historic cathedral city that was once the capital of England. Hampshire is notable for housing the original birthplaces of the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force...

, Portsmouth

Portsmouth

Portsmouth is the second largest city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire on the south coast of England. Portsmouth is notable for being the United Kingdom's only island city; it is located mainly on Portsea Island...

and Southampton

Southampton

Southampton is the largest city in the county of Hampshire on the south coast of England, and is situated south-west of London and north-west of Portsmouth. Southampton is a major port and the closest city to the New Forest...

Assizes

Assizes (England and Wales)

The Courts of Assize, or Assizes, were periodic criminal courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the Quarter Sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court...

.

To supplement his income and help pay for his legal training, Druitt worked as an assistant schoolmaster at George Valentine's boarding school

Boarding school

A boarding school is a school where some or all pupils study and live during the school year with their fellow students and possibly teachers and/or administrators. The word 'boarding' is used in the sense of "bed and board," i.e., lodging and meals...

, 9 Eliot Place, Blackheath, London

Blackheath, London

Blackheath is a district of South London, England. It is named from the large open public grassland which separates it from Greenwich to the north and Lewisham to the west...

, from 1880. The school had a long and distinguished history; Benjamin Disraeli had been a pupil there in the 1810s, and boys from the school had been playmates of a younger son of Queen Victoria

Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, who as a boy in the 1860s had lived nearby at Greenwich Park

Greenwich Park

Greenwich Park is a former hunting park in Greenwich and one of the largest single green spaces in south east London. One of the Royal Parks of London, and the first to be enclosed , it covers , and is part of the Greenwich World Heritage Site. It commands fine views over the River Thames, Isle of...

. Druitt's post came with accommodation in Eliot Place, and the long school holidays gave him time to study the law and to pursue his interest in cricket.

Cricket

In Dorset, Druitt played for the Kingston Park Cricket Club, and the Dorset County Cricket ClubDorset County Cricket Club

Dorset County Cricket Club is one of the county clubs which make up the Minor Counties in the English domestic cricket structure, representing the historic county of Dorset and playing in the Minor Counties Championship and the MCCA Knockout Trophy...

. He was particularly noted for his skill as a bowler. In 1882 and 1883, he toured the West Country

West Country

The West Country is an informal term for the area of south western England roughly corresponding to the modern South West England government region. It is often defined to encompass the historic counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset and Somerset and the City of Bristol, while the counties of...

with a gentleman's touring team called the Incogniti

Incogniti

The Incogniti cricket club was founded in 1861, claims to be the third oldest "wandering" cricket club – a nomadic cricket club without its own home ground – after I Zingari and Free Foresters ....

. One of Druitt's fellow local players was Francis Lacey

Francis Lacey

Sir Francis Eden Lacey was the first man to be knighted for services to cricket, on retiring as Secretary of MCC, a post which he held from 1898 to 1926. As Secretary, he initiated many important reforms...

, the first man knighted for services to cricket. Druitt played for another wandering team, the Butterflies, on 14 June 1883, when they drew against his alma mater Winchester College. The team included first-class cricketers A. J. Webbe, J. G. Crowdy

James Crowdy (cricketer)

James Gordon Crowdy was an English cricketer. Crowdy was a right-handed batsman.Crowdy made his first-class debut for the Marylebone Cricket Club in the 1872 season. Crowdy played an single match for the club against Oxford University.In 1875 Crowdy made his first-class debut for Hampshire against...

, John Frederick

John Frederick (cricketer)

John St John Frederick was an English cricketer who played as a right-handed batsman and a right-arm roundarm fast bowler.Frederick made his first-class debut for Oxford University 1864 against the Marylebone Cricket Club...

and Charles Seymour

Charles Seymour (cricketer)

Charles Read Seymour was an English cricketer. Seymour was a right-handed batsman.The son of a Reverend, Seymour was educated at Harrow, and was later educated at Merton College, Oxford, where he took his B.A. in 1877....

.

While working at Blackheath, Druitt joined the local cricket club, Blackheath Morden, and became the club's treasurer. It was a well-connected club: the President was politician Sir Charles Mills

Charles Mills, 1st Baron Hillingdon

Charles Henry Mills, 1st Baron Hillingdon , known as Sir Charles Mills, 2nd Baronet, from 1872 to 1886, was a British banker and Conservative politician....

and one of its players was Stanley Christopherson

Stanley Christopherson

Stanley Christopherson was the best of the ten Christopherson brothers who played the sport of cricket as an amateur in Kent in the late 19th century...

. After the merger of the club with other local sports associations to form the Blackheath Cricket, Football and Lawn Tennis Company

Rectory Field

Rectory Field is a playing field in Blackheath, London. It was developed in the 1880s by Blackheath Cricket, Football and Lawn Tennis Company and became the home of Kent County Cricket Club and rugby union team Blackheath F.C....

, Druitt took on the additional roles of company secretary and director. The inaugural game of the new club was played against George Gibbons Hearne

George Gibbons Hearne

George Gibbons Hearne was a cricketer who played first-class cricket for Kent between 1875 and 1895. He also played in one Test match for England against South Africa in 1891-92. Hearne was part of the famous cricketing Hearne family...

's Eleven, which included many members of the famous cricketing Hearne family

Hearne family

The Hearne family is an English cricketing family. Twelve members of the family played first-class cricket, including five for Kent and five for Middlesex...

. Hearne's team won by 21 runs. On 5 June 1886, in a match between Blackheath and a gentleman's touring team called the Band of Brothers, led by Lord Harris

George Harris, 4th Baron Harris

George Robert Canning Harris, 4th Baron Harris, GCSI, GCIE was a British politician, cricketer and cricket administrator...

, Druitt bowled Harris for 14 and took three other wickets. Blackheath won by 178 runs. Two weeks later, he dismissed England batsman John Shuter

John Shuter

John Shuter was a cricketer who played for England and Surrey in the late 19th century...

, who was playing for Bexley Cricket Club

Bexley Cricket Club

Bexley Cricket Club was founded in 1805 at the Manor Way ground in Bexley Village. The club has historically been one of the strongest in South-East England, having been Kent Cricket League champions in 1996, and appearing in two Evening Standard Challenge Trophy finals. Bexley fields six teams on...

, for a duck

Duck (cricket)

In the sport of cricket, a duck refers to a batsman's dismissal for a score of zero.-Origin of the term:The term is a shortening of the term "duck's egg", the latter being used long before Test cricket began...

, and Blackheath won the game by 114 runs. The following year, Shuter returned to Blackheath with a Surrey County side

Surrey County Cricket Club

Surrey County Cricket Club is one of the 18 professional county clubs which make up the English and Welsh domestic cricket structure, representing the historic county of Surrey. Its limited overs team is called the Surrey Lions...

that included Walter Read

Walter Read

Walter William Read was an English cricketer, who was a fluent right hand bat. An occasional bowler of lobs, he sometimes switched to quick overarm deliveries. He captained England in two Test matches, winning them both...

, William Lockwood

William Lockwood

William 'Bill' Lockwood William 'Bill' Lockwood William 'Bill' Lockwood (William Henry Lockwood; born 25 March 1868, Radford, Nottingham; died 26 April 1932, Radford, Nottingham was a fast bowler and the unpredictable, occasionally devastating counterpart to the amazingly hard-working Tom...

, and Bobby Abel

Bobby Abel

Robert Abel , nicknamed "The Guv'nor", was a Surrey and England opening batsman who was one of the most prolific run-getters in the early years of the County Championship...

, whom Druitt bowled out for 56. Surrey won by 147 runs.

On 26 May 1884, Druitt was elected to the Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club is a cricket club in London founded in 1787. Its influence and longevity now witness it as a private members' club dedicated to the development of cricket. It owns, and is based at, Lord's Cricket Ground in St John's Wood, London NW8. MCC was formerly the governing body of...

(MCC) on the recommendation of his fellow Butterflies player Charles Seymour, who proposed him, and noted fielder Vernon Royle

Vernon Royle

The Reverend Vernon Peter Fanshawe Archer Royle . He was the son of Dr. Peter Royle and Marina Fanshawe. He played cricket for Oxford University and Lancashire. He was a member of Lord Harris's cricket team to tour Australia in 1878/9...

, who seconded his nomination. One of the minor matches he played for MCC was with England bowler William Attewell

William Attewell

William Attewell was a cricketer who played for Nottinghamshire County Cricket Club and England. Attewell was a medium pace bowler who was renowned for his extraordinary accuracy and economy...

against Harrow School

Harrow School

Harrow School, commonly known simply as "Harrow", is an English independent school for boys situated in the town of Harrow, in north-west London.. The school is of worldwide renown. There is some evidence that there has been a school on the site since 1243 but the Harrow School we know today was...

on 10 June 1886. MCC won by 57 runs. He also played against MCC for Blackheath: on 23 July 1887, he bowled out Dick Pougher

Dick Pougher

Arthur Dick Pougher was a cricketer who played for Leicestershire County Cricket Club between 1894 and 1901. Pougher was awarded a benefit by Leicestershire in 1900...

for 28 runs, but Druitt only made 5 runs before he was bowled out by Arnold Fothergill

Arnold Fothergill

Arnold James Fothergill was an English cricketer.Despite having been born in Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland, Fothergill played first-class cricket for Somerset County Cricket Club between 1882 and 1884...

with a ball caught by Pougher. MCC won by 52 runs.

In June 1888, Lord Harris played twice for Blackheath with Druitt and Stanley Christopherson; Blackheath won both matches easily, but Druitt was off form and contributed neither runs nor wickets in either match. In August 1888, Druitt played for the Gentlemen of Bournemouth

Bournemouth

Bournemouth is a large coastal resort town in the ceremonial county of Dorset, England. According to the 2001 Census the town has a population of 163,444, making it the largest settlement in Dorset. It is also the largest settlement between Southampton and Plymouth...

against the Parsees cricket team

Parsees cricket team

The Parsees cricket team was an Indian first-class cricket team which took part in the annual Bombay tournament. The team was founded by members of the Zoroastrian community in Bombay....

during their tour of England

Parsee cricket team in England in 1888

The Parsees made their second tour of England in 1888. The fifteen member team played mostly against amateur teams and was more successful than the tourists of 1886.-The tour:...

, and took five wickets in the visitors' first innings. Nevertheless, the Parsees won. On 8 September 1888, the Blackheath Club played against the Christopherson brothers. Druitt was bowled out by Stanley Christopherson, who was playing with his brothers instead of for Blackheath, and in reply Druitt bowled out Christopherson. Blackheath won by 22 runs.

In addition to cricket, Druitt also participated in field hockey.

Death

On Friday 30 November 1888, Druitt was dismissed from his post at the Blackheath boys' school. The reason for his dismissal is unclear. One newspaper, quoting his brother William's inquest testimony, reported that he was dismissed because he "had got into serious trouble", but did not specify any further. In early December 1888, he disappeared, and on 21 December 1888 the Blackheath Cricket Club's minute book records that he was removed as treasurer and secretary in the belief that he had "gone abroad".On 31 December 1888, his body was found floating in the River Thames

River Thames

The River Thames flows through southern England. It is the longest river entirely in England and the second longest in the United Kingdom. While it is best known because its lower reaches flow through central London, the river flows alongside several other towns and cities, including Oxford,...

, off Thornycroft's

John I. Thornycroft & Company

John I. Thornycroft & Company Limited, usually known simply as Thornycroft was a British shipbuilding firm started by John Isaac Thornycroft in the 19th century.-History:...

torpedo works, Chiswick

Chiswick

Chiswick is a large suburb of west London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It is located on a meander of the River Thames, west of Charing Cross and is one of 35 major centres identified in the London Plan. It was historically an ancient parish in the county of Middlesex, with...

, by a waterman named Henry Winslade. Stones in Druitt's pockets had kept his body submerged for about a month. He was carrying a train ticket to Hammersmith dated 1 December, a silver watch, a cheque for £50 and £16 in gold (equivalent to £ and £ today). It is not known why he should have carried such a large amount of money, but it could have been a final payment from the school.

Some modern authors suggest that Druitt was dismissed because he was a homosexual or pederast and that it may have driven him to suicide. One speculation is that the money found on his body was going to be used for payment to a blackmailer. Others, however, think that there is no evidence of homosexuality and that his suicide was instead precipitated by an hereditary psychiatric illness. His mother suffered from depression and was institutionalised from July 1888. She died in an asylum in Chiswick in 1890. His maternal grandmother committed suicide while insane; his aunt attempted suicide; and his eldest sister committed suicide in old age. A note written by Druitt and addressed to his brother William, who was a solicitor in Bournemouth, was found in Druitt's room in Blackheath. It read, "Since Friday I felt that I was going to be like mother, and the best thing for me was to die."

As was usual in the district, the inquest was held at the Lamb Tap public house

Public house

A public house, informally known as a pub, is a drinking establishment fundamental to the culture of Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand. There are approximately 53,500 public houses in the United Kingdom. This number has been declining every year, so that nearly half of the smaller...

, Chiswick, by the coroner Dr Thomas Bramah Diplock on 2 January 1889. The coroner's jury concluded that Druitt had committed suicide by drowning while in an unsound state of mind. He was buried in Wimborne cemetery the next day. At probate, his estate was valued at £2,600 (equivalent to £ today).

It is not known why Druitt committed suicide in Chiswick. One suggested link is that one of his University friends, Thomas Seymour Tuke of the Tuke family

Tuke family

The Tuke family of York were "a remarkable family of Quaker innovators". They were involved in establishing*Rowntree's Cocoa Works*The Retreat Mental Hospital*three Quaker schools - Ackworth, Bootham, and The Mount.They included four generations...

, lived there. Tuke was a psychiatric doctor with whom Druitt played cricket, and Druitt's mother was committed to Tuke's asylum in 1890. Another suggestion is that Druitt knew Harry Wilson, whose house, "The Osiers", lay between Hammersmith station and Thornycroft's wharf, where Druitt's body was found.

Jack the Ripper suspect

Mary Ann Nichols

Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols was one of the Whitechapel murder victims. Her death has been attributed to the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who is believed to have killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.- Life...

was found murdered in the impoverished Whitechapel

Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a built-up inner city district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, London, England. It is located east of Charing Cross and roughly bounded by the Bishopsgate thoroughfare on the west, Fashion Street on the north, Brady Street and Cavell Street on the east and The Highway on the...

district in the East End of London

East End of London

The East End of London, also known simply as the East End, is the area of London, England, United Kingdom, east of the medieval walled City of London and north of the River Thames. Although not defined by universally accepted formal boundaries, the River Lea can be considered another boundary...

. Her throat was slashed. During September, three more women (Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman

Annie Chapman , born Eliza Ann Smith, was a victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated five women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.-Life and background:Annie Chapman was born Eliza Ann Smith...

on the 8th and Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth Stride

Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride is believed to be the third victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer called Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated prostitutes in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888.She was nicknamed "Long Liz"...

and Catherine Eddowes

Catherine Eddowes

Catherine Eddowes was one of the victims in the Whitechapel murders. She was the second person killed on the night of Sunday 30 September 1888, a night which already had seen the murder of Elizabeth Stride less than an hour earlier...

on the 30th) were found dead with their throats cut. On 9 November 1888, the body of Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly , also known as "Marie Jeanette" Kelly, "Fair Emma", "Ginger" and "Black Mary", is widely believed to be the fifth and final victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated prostitutes in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to...

was discovered. Her throat had been severed down to the spine. In four of the cases the bodies were mutilated after death. The similarities between the crimes led to the supposition that they were committed by the same assailant, who was given the nickname "Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper

"Jack the Ripper" is the best-known name given to an unidentified serial killer who was active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. The name originated in a letter, written by someone claiming to be the murderer, that was disseminated in the...

". Despite an extensive police investigation into the five murders, the Ripper was never identified and the crimes remained unsolved.

Shortly after Kelly's murder, stories that the Ripper had drowned in the Thames began to circulate. In February 1891, the MP for West Dorset, Henry Richard Farquharson

Henry Richard Farquharson

Henry Richard Farquharson was an English landowner and Conservative politician.Farquharson was born at Brighton and became the owner of a large estate at Eastbury House, Tarrant Gunville . He was a fanatical breeder of Newfoundland dogs and had a pack of one hundred and twenty five...

, announced that Jack the Ripper was "the son of a surgeon" who had committed suicide on the night of the last murder. Although Farquharson did not name his suspect, the description resembles Druitt. Farquharson lived 10 miles (16 km) from the Druitt family and was part of the same social class. The Victorian journalist George R. Sims noted in his memoirs, The Mysteries of Modern London (1906), "[the Ripper's] body was found in the Thames after it had been in the river for about a month". Similar comments were made by Sir John Moylan, Assistant Under-Secretary of the Home Office: "[the Ripper] escaped justice by committing suicide at the end of 1888" and Sir Basil Thomson

Basil Thomson

Sir Basil Home Thomson, KCB was a British intelligence officer, police officer, prison governor, colonial administrator, and writer.-Early life:...

, made Assistant Commissioner of the CID in 1913: "[the Ripper was] an insane Russian doctor [who] escaped arrest by committing suicide in the Thames at the end of 1888". Neither Moylan nor Thomson was involved in the investigation.

Assistant Chief Constable

Chief Constable

Chief constable is the rank used by the chief police officer of every territorial police force in the United Kingdom except for the City of London Police and the Metropolitan Police, as well as the chief officers of the three 'special' national police forces, the British Transport Police, Ministry...

Sir Melville Macnaghten

Melville MacNaghten

Sir Melville Leslie Macnaghten CB KPM was Assistant Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police from 1903 to 1913....

named Druitt as a suspect in the case in a private handwritten memorandum of 23 February 1894. Macnaghten highlighted the coincidence between Druitt's disappearance and death shortly after the last of the five murders on 9 November 1888, and claimed to have unspecified "private information" that left "little doubt" Druitt's own family believed him to have been the murderer. Macnaghten's memo was eventually discovered in his personal papers by his daughter, Lady Aberconway, who showed them to British broadcaster Dan Farson. A slightly different abridged copy of the memo found in the Metropolitan Police archive was released to the public in 1966. Farson first revealed Druitt's initials "MJD" in a television programme in November 1959. In 1961, Farson investigated a claim by an Australian that Montague's cousin, Lionel Druitt, had written a pamphlet that claimed knowledge of the Ripper's identity, but the claim was never substantiated. Journalist Tom Cullen revealed Druitt's full name in his 1965 book Autumn of Terror, which was followed by Farson's 1972 book Jack the Ripper. Before the discovery of Macnaghten's memo, books on the Ripper case, such as those written by Leonard Matters

Leonard Matters

Leonard Warburton Matters was an Australian journalist who became a Labour Party politician in the United Kingdom.He was born a British subject in Adelaide, Australia, and fought in the Second Boer War in South Africa...

and Donald McCormick

Donald McCormick

George Donald King McCormick was a British journalist and popular historian, who also wrote under the pseudonyms Richard Deacon and Lichade Digen....

, poured scorn on stories that the Ripper had drowned in the Thames because they could not find a suicide that matched the description of the culprit. Cullen and Farson, however, supposed that Druitt was the Ripper on the basis of the Macnaghten memorandum, the near coincidence between Druitt's death and the end of the murders, the closeness of Whitechapel to Druitt's rooms in the Inner Temple, the insanity that was acknowledged by the inquest verdict of "unsound mind", and the possibility that Druitt had absorbed the rudimentary anatomical skill supposedly shown by the Ripper through observing his father at work.

Since the publication of Cullen's and Farson's books, other Ripper authors have argued that their theories are based solely on flawed circumstantial evidence, and have attempted to provide Druitt with alibis for the times of the murders. On 1 September, the day after the murder of Nichols, Druitt was in Dorset playing cricket. On the day of Chapman's murder, he played cricket in Blackheath, and the day after the murders of Stride and Eddowes, he was in the West Country defending a client in a court case. While writers Andrew Spallek and Tom Cullen argue that Druitt had the time and opportunity to travel by train between London and his cricket and legal engagements, or use his city chambers as a base from which to commit the murders, others dismiss the possibility as "improbable". Many experts believe that the killer was local to Whitechapel, whereas Druitt lived miles away on the other side of the River Thames. His chambers were within walking distance of Whitechapel, and his regular rail commute would almost certainly have brought him to Cannon Street station

Cannon Street station

Cannon Street station, also known as London Cannon Street, is a central London railway terminus and London Underground complex in the City of London, England. It is built on the site of the medieval Steelyard, the trading base in England of the Hanseatic League...

, a few minutes' walk from the East End. It seems unlikely, however, that he could have travelled the distance in blood-stained clothes unnoticed, and a clue discovered during the investigation into the murder of Catherine Eddowes (a piece of her blood-stained clothing

Goulston Street graffito

The Goulston Street graffito was some writing on a wall that was found beside a clue in the Whitechapel murders investigation. The Whitechapel murders were a series of brutal attacks on women in the Whitechapel district in the East End of London that occurred between 1888 and 1891...

) indicates that the murderer travelled north-east from where she was murdered, but Druitt's chambers and the railway station were south-westwards.

Macnaghten incorrectly described Druitt as a 41-year-old doctor, and cited allegations that he "was sexually insane" without specifying the source or details of the allegations. Macnaghten did not join the force until 1889, after the murder of Kelly and the death of Druitt, and was not involved in the investigation directly. Macnaghten's memorandum named two other suspects ("Kosminski"

Aaron Kosminski

Aaron Kosminski was an insane Polish Jew who was a suspect in the Jack the Ripper murders. He emigrated to England from Poland in the 1880s and worked as a hairdresser in Whitechapel in the East End of London, where the murders were committed in 1888...

and Michael Ostrog) and was written to refute allegations against a fourth, Thomas Cutbush. The three Macnaghten suspects—Druitt, Kosminski and Ostrog—also match the descriptions of three unnamed suspects in Major Arthur Griffiths' Mysteries of Police and Crime (1898); Griffiths was Inspector of Prisons at the time of the Ripper murders. Inspector Frederick Abberline

Frederick Abberline

Frederick George Abberline was a Chief Inspector for the London Metropolitan Police and was a prominent police figure in the investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.-Early life:...

, who was the lead investigative officer in the case, appeared to dismiss Druitt as a suspect on the basis that the only evidence against him was the coincidental timing of his suicide shortly after the fifth murder. Other officials involved in the Ripper case, Metropolitan Police Commissioner

Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis

The Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis is the head of London's Metropolitan Police Service, classing the holder as a chief police officer...

James Monro

James Monro

James Monro CB was a lawyer who became the first Assistant Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police and also served as Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis from 1888 to 1890.-Early career:...

and pathologist Thomas Bond

Thomas Bond (British physician)

Dr Thomas Bond FRCS, MB BS , was a British surgeon considered by some to be the first offender profiler, and best known for his association with the notorious Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.-Early life:...

, believed that the murder of Alice McKenzie on 17 July 1889, seven months after Druitt's death, was committed by the same culprit as the earlier murders. The inclusion of McKenzie among the Ripper's victims was contested by Abberline and Macnaghten among others, but if she was one of his victims, then Druitt clearly could not be the Ripper. Another murder occasionally included among the Ripper cases is that of Martha Tabram

Martha Tabram

Martha Tabram was an English prostitute whose killing was the second of the Whitechapel murders in late 19th century London...

, who was viciously stabbed to death on 7 August 1888. Her death coincided with the middle of Bournemouth Cricket Week, 4–11 August, in which Druitt was heavily involved, and was in the school holiday, which Druitt spent in Dorset. In the words of one of his biographers, "It scarcely left time for a 200-mile round dash to fit in a murder."

Legacy

Druitt was a favoured suspect in the Jack the Ripper crimes throughout the 1960s, until the advent of theories in the 1970s that the murders were not the work of a single serial killer but the result of a conspiracy involving the British royal familyBritish Royal Family

The British Royal Family is the group of close relatives of the monarch of the United Kingdom. The term is also commonly applied to the same group of people as the relations of the monarch in her or his role as sovereign of any of the other Commonwealth realms, thus sometimes at variance with...

and Freemasonry

Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organisation that arose from obscure origins in the late 16th to early 17th century. Freemasonry now exists in various forms all over the world, with a membership estimated at around six million, including approximately 150,000 under the jurisdictions of the Grand Lodge...

. The theories are widely condemned as ridiculous, and implicate Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, his tutor James Stephen

James Kenneth Stephen

James Kenneth Stephen was an English poet, and tutor to Prince Albert Victor, eldest son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.-Early life:...

, and their doctor Sir William Gull to varying degrees. One version of the conspiracy promoted by Stephen Knight in his 1976 book Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution supposed that Druitt was a scapegoat, chosen by officialdom to take the blame for the murders. Martin Howells and Keith Skinner followed the same line in their 1987 book The Ripper Legacy, which was panned by one critic as being based on "no evidence whatever".

The theories attempted to link Druitt with Clarence, Gull and Stephen through a network of mutual acquaintances and possible connections. Reginald Acland

Reginald Acland

Sir Reginald Brodie Dyke Acland KC, JP was a British barrister and judge.-Background:He was the sixth son of Sir Henry Wentworth Acland, 1st Baronet and his wife Sarah Cotton, eldest daughter of William Cotton. His younger brother was Alfred Dyke Acland...

, the brother of Gull's son-in-law, had legal chambers in King's Bench Walk near Druitt's, as did Harry Stephen, who was James Stephen's brother. Harry Stephen was good friends with Harry Wilson, who had a house in Chiswick, "The Osiers", near to where Druitt's body was found. Wilson and James Stephen were close friends of Clarence, and were both members of an exclusive society called the Cambridge Apostles

Cambridge Apostles

The Cambridge Apostles, also known as the Cambridge Conversazione Society, is an intellectual secret society at the University of Cambridge founded in 1820 by George Tomlinson, a Cambridge student who went on to become the first Bishop of Gibraltar....

. As a schoolboy, Druitt had played cricket against two of Wilson's friends, Kynaston Studd

Kynaston Studd

Sir John Edward Kynaston Studd, 1st Baronet OBE , known as "JEK", was a British cricketer, businessman and Lord Mayor of London.-Family:...

and Henry Goodhart, who was also one of the Apostles. Another potential connection between Druitt and Wilson is through John Henry Lonsdale. Lonsdale's name and Blackheath address are written in a diary belonging to Wilson now in the possession of Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellows...

. Lonsdale's address is a few yards from the school at which Druitt worked and lived, and Lonsdale had been a barrister and had also rented legal chambers in King's Bench Walk. In 1887, Lonsdale entered the church and was assigned as curate to Wimborne Minster, where the Druitt family worshiped. Lonsdale and Macnaghten were classmates at Eton

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

, and so theorists argue that Lonsdale might have been in a position to provide "private information" to Macnaghten regarding Druitt. The connections between the Apostles and Druitt led to the suggestion that he was part of the same social set. Druitt, his mother and his sister Georgiana were invited to a ball in honour of Clarence at the home of Lord Wimborne on 17 December 1888, although they did not attend because by that time Montague was dead, his mother was in an asylum, and his sister was expecting her second child. Clarence, Stephen, Wilson, Studd, and Goodhart are suggested to have been homosexual, although this is contested by historians. John Wilding's 1993 book Jack the Ripper Revealed used the connections between Druitt and Stephen to propose that they committed the crimes together, but reviewers considered it an "imaginative tale ... most questionable", an "exercise in ingenuity rather than ... fact", and "lack[ing] evidential support".

In his 2005 and 2006 biographies of Druitt, D. J. Leighton concluded that Druitt was innocent, but repeated some of Knight's and Wilding's discredited claims. Leighton suggested that Druitt could have been murdered either out of greed by his elder brother William or, as previously suggested by Howells and Skinner, out of fear of exposure by Harry Wilson's homosexual cronies. The propensity of theorists to associate Ripper suspects with homosexuality has led scholars to assume that such notions are based on homophobia

Homophobia

Homophobia is a term used to refer to a range of negative attitudes and feelings towards lesbian, gay and in some cases bisexual, transgender people and behavior, although these are usually covered under other terms such as biphobia and transphobia. Definitions refer to irrational fear, with the...

rather than evidence.

The accusations against Clarence, Stephen, Gull and Druitt also draw on cultural perceptions of a decadent aristocracy, and depict an upper-class murderer or murderers preying on lower-class victims. As Druitt and the other aristocratic Ripper suspects were wealthy, there is more biographical material on them than on the residents of the Whitechapel

Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a built-up inner city district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, London, England. It is located east of Charing Cross and roughly bounded by the Bishopsgate thoroughfare on the west, Fashion Street on the north, Brady Street and Cavell Street on the east and The Highway on the...

slums. Consequently, it is easier for writers to construct solutions based on a wealthy culprit rather than one based on a Whitechapel resident. There is no direct evidence against Druitt, and since the 1970s, the number of Jack the Ripper suspects has continued to grow, with the result that there are now over 100 different theories about the Ripper's identity.

Fiction

In fiction, Druitt is depicted as the murderer in the musical Jack the Ripper by Ron Pember and Denis de Marne. In John Gardner's Sherlock HolmesSherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes is a fictional detective created by Scottish author and physician Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The fantastic London-based "consulting detective", Holmes is famous for his astute logical reasoning, his ability to take almost any disguise, and his use of forensic science skills to solve...

story The Revenge of Moriarty, Professor Moriarty

Professor Moriarty

Professor James Moriarty is a fictional character and the archenemy of the detective Sherlock Holmes in the fiction of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Moriarty is a criminal mastermind, described by Holmes as the "Napoleon of Crime". Doyle lifted the phrase from a real Scotland Yard inspector who was...

's criminal exploits are hampered by increased police activity as a result of the Jack the Ripper murders. He discovers that Druitt is the murderer and so fakes his suicide in the hope that the police will lose interest once the murders cease. The TV series Sanctuary depicts John Druitt as a scientist with the ability to teleport. Druitt is inhabited by an evil energy being, goes mad and becomes Jack the Ripper. His ability to teleport explains how he committed the murders when historical records show him distant from the crime scenes. In the anime Kuroshitsuji, the Viscount of Druitt is a suspect in the murders of several prostitutes, also dubbed the "Jack the Ripper" case. In Alan Moore

Alan Moore

Alan Oswald Moore is an English writer primarily known for his work in comic books, a medium where he has produced a number of critically acclaimed and popular series, including Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and From Hell...

and Eddie Campbell

Eddie Campbell

Eddie Campbell is a Scottish comics artist and cartoonist who now lives in Australia. Probably best known as the illustrator and publisher of From Hell , Campbell is also the creator of the semi-autobiographical Alec stories collected in Alec: The Years Have Pants, and Bacchus , a wry adventure...

's graphic novel From Hell

From Hell

From Hell is a comic book series by writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell, originally published from 1991 to 1996, speculating upon the identity and motives of Jack the Ripper. The title is taken from the first words of the "From Hell" letter, which some authorities believe was an authentic...