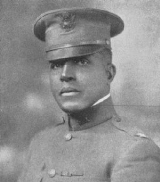

Charles Young

Encyclopedia

Charles Young was the third African American

graduate of West Point, the first black U.S. national park

superintendent, first black military attaché

, first black to achieve the rank of colonel

, and highest-ranking black officer in the United States Army

until his death in 1922.

to Gabriel Young and Arminta Bruen in May's Lick, Kentucky

, a small village near Maysville

, but he grew up a free person. His father Gabriel escaped from slavery, in 1865 going across the Ohio River

to Ripley, Ohio

to enlist as a private in the Fifth Regiment of the Colored Artillery (Heavy) Volunteers during the American Civil War

. Accounts differ as to whether he took his wife and child with him then. His service earned him and his wife freedom. As a young woman Arminta had learned to read and write, and may have had status as a house slave before becoming free.

After the war, the entire family migrated to Ripley in 1866, where the parents decided opportunities were better than in postwar Kentucky. Gabriel had earned a bonus by continuing to serve in the Army after the war and had a stake to buy land. As a youth, Charles Young attended the all-white high school

in Ripley, the only one available. He graduated at age 16 at the top of his class. Following graduation, he taught school for a few years at the newly established black high school of Ripley.

at West Point. He achieved the second highest score in the district in 1883, and after the primary candidate dropped out, Young reported to the academy in 1884. He was not the only black student in the academy,(John Hanks Alexander

entered West Point Military Academy in 1883 and graduated in 1887, Alexander and Young shared a room for three years at West Point). Young made some lifelong friends among his classmates. He had to repeat his first year because of failing mathematics. Failing an engineering class later, he passed after being personally tutored during the summer by George Washington Goethals

, a brilliant engineer and assistant professor who took an interest in him. (Goethals later directed construction of the Panama Canal

.) It was not unusual for candidates to require additional help in some subjects. Young's strength was in languages, and he learned several.

Young graduated with his commission as a second lieutenant in 1889, the third black man to do so at the time. He was first assigned to the Tenth U.S. Cavalry Regiment

. Through a reassignment, he served first with the Ninth U.S. Cavalry Regiment, serving first in Nebraska. His subsequent service of 28 years was chiefly with black troops — the Ninth U.S. Cavalry and the Tenth U.S. Cavalry

, black troops nicknamed the "Buffalo Soldiers" since the Indian Wars

. The armed services were racially segregated

until 1948, when President Harry S. Truman

integrated them by Executive order.

. They had two children: Charles Noel, born in 1906 in Ohio, and Marie Aurelia, born in 1909 when Young and his family were stationed in the Philippines

.

Young began his service with the Ninth Cavalry in the American West: from 1889-1890 he served at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, and from 1890-1894 at Fort Duchesne, Utah

Young began his service with the Ninth Cavalry in the American West: from 1889-1890 he served at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, and from 1890-1894 at Fort Duchesne, Utah

.

Beginning in 1894 as a lieutenant, Young was assigned to Wilberforce College

in Ohio, a historically black college (HBCU), to lead the new military sciences department, which was established under a special federal grant. As a professor for four years, he was one of a number of outstanding men on the staff, including W.E.B. Du Bois

, with whom he became friends.

. When appointed acting superintendent

of Sequoia

and General Grant national park

s, he was the first black superintendent of a national park. At the time the military supervised the parks. Because of limited funding, the Army assigned personnel for short-term assignments during the summers, making it difficult for the officers to accomplish longer term goals, such as construction of infrastructure. Young supervised payroll accounts

and directed the activities of rangers

.

Young's greatest impact on the park was managing road

construction, which helped to improve the underdeveloped park and enable more visitors to travel within it. Young and his troops accomplished more that summer than had teams under the three military officers who had been assigned the previous three summers. Captain Young and his troops completed a wagon road to the Giant Forest, home of the world's largest trees, and a road to the base of the famous Moro Rock

. By mid-August, wagons of visitors were able to enter the mountaintop forest for the first time.

With the end of the brief summer construction season, Young was transferred on November 2, 1903, and reassigned as the troop commander of the Tenth Cavalry at the Presidio. In his final report on Sequoia Park to the Secretary of the Interior

, he recommended the government

acquire privately held lands there, to secure more park area for future generations. This recommendation was noted in legislation to that purpose introduced in the United States House of Representatives

.

In 1908 Young was sent to the Philippines

to join his Ninth Regiment and command a squadron of two troops. It was his second tour there. After his return to the US, he served for two years at Fort D.A. Russell, Wyoming.

In 1912 Young was assigned as military attaché

in Liberia, the first African American to hold that post. For three years, he served as an expert adviser to the Liberian Government and also took a direct role, supervising construction of the country's infrastructure. For his achievements, in 1916 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

(NAACP) awarded Young the Spingarn Medal

, given annually to the African American demonstrating the highest achievement and contributions.

During the 1916 Punitive Expedition

by the United States into Mexico

, then Major Young commanded the 2nd squadron of the 10th United States Cavalry. While leading a cavalry pistol charge against Pancho Villa

's forces at Agua Caliente (1 April 1916), he routed the opposing forces without losing a single man. His swift action saved the wounded General Beltran

and his men of the 13th Cavalry squadron, who had been outflanked.

Because of his exceptional leadership of the 10th Cavalry in the Mexican theater of war, Young was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in September 1916. He was assigned as commander of Fort Huachuca

, the base in Arizona

of the Tenth Cavalry, nicknamed the "Buffalo Soldiers", until mid 1917. He was the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel in the US Army. With the outbreak of World War I

, Young likely hoped for a chance to gain a promotion to general. Resistance to black officers and health problems meant he never reached this goal. He was sidelined by a diagnosis of high blood pressure

, which forced him to accept a medical furlough, and was placed temporarily on the inactive list on June 22, 1917.

He returned to Wilberforce University, where he was a Professor of Military Science through most of 1918. On November 6, 1918, after Young traveled by horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio

to Washington, D.C.

to prove his physical fitness, he was reinstated on active duty in the Army and promoted to full Colonel. In 1919, he was assigned again as military attaché to Liberia.

Young died January 8, 1922 of a kidney infection while on a reconnaissance

mission in Nigeria

. His body was returned to the United States, where he was given a full military funeral and buried at Arlington National Cemetery

near Washington, DC. He had become a public and respected figure because of his unique achievements in the US Army, and his obituary was carried in the New York Times.

This article is based in part on a document created by the National Park Service

, which is part of the U.S. government. As such, it is presumed to be in the public domain.

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

graduate of West Point, the first black U.S. national park

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

superintendent, first black military attaché

Military attaché

A military attaché is a military expert who is attached to a diplomatic mission . This post is normally filled by a high-ranking military officer who retains the commission while serving in an embassy...

, first black to achieve the rank of colonel

Colonel

Colonel , abbreviated Col or COL, is a military rank of a senior commissioned officer. It or a corresponding rank exists in most armies and in many air forces; the naval equivalent rank is generally "Captain". It is also used in some police forces and other paramilitary rank structures...

, and highest-ranking black officer in the United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

until his death in 1922.

Early life and education

Charles Young was born in 1864 into slaverySlavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

to Gabriel Young and Arminta Bruen in May's Lick, Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, a small village near Maysville

Maysville, Kentucky

Maysville is a city in and the county seat of Mason County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 8,993 at the 2000 census, making it the fiftieth largest city in Kentucky by population. Maysville is on the Ohio River, northeast of Lexington. It is the principal city of the Maysville...

, but he grew up a free person. His father Gabriel escaped from slavery, in 1865 going across the Ohio River

Ohio River

The Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

to Ripley, Ohio

Ripley, Ohio

Ripley is a village in Brown County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River 50 miles southeast of Cincinnati. The population was 1,745 at the 2000 census.-History:...

to enlist as a private in the Fifth Regiment of the Colored Artillery (Heavy) Volunteers during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. Accounts differ as to whether he took his wife and child with him then. His service earned him and his wife freedom. As a young woman Arminta had learned to read and write, and may have had status as a house slave before becoming free.

After the war, the entire family migrated to Ripley in 1866, where the parents decided opportunities were better than in postwar Kentucky. Gabriel had earned a bonus by continuing to serve in the Army after the war and had a stake to buy land. As a youth, Charles Young attended the all-white high school

High school

High school is a term used in parts of the English speaking world to describe institutions which provide all or part of secondary education. The term is often incorporated into the name of such institutions....

in Ripley, the only one available. He graduated at age 16 at the top of his class. Following graduation, he taught school for a few years at the newly established black high school of Ripley.

West Point

While teaching, Young took a competitive examination for appointment as a cadet at United States Military AcademyUnited States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy at West Point is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located at West Point, New York. The academy sits on scenic high ground overlooking the Hudson River, north of New York City...

at West Point. He achieved the second highest score in the district in 1883, and after the primary candidate dropped out, Young reported to the academy in 1884. He was not the only black student in the academy,(John Hanks Alexander

John Hanks Alexander

John Hanks Alexander was the first African American officer in the United States armed forces to hold a regular command position and the second African American graduate of the United States Military Academy.-Early life:...

entered West Point Military Academy in 1883 and graduated in 1887, Alexander and Young shared a room for three years at West Point). Young made some lifelong friends among his classmates. He had to repeat his first year because of failing mathematics. Failing an engineering class later, he passed after being personally tutored during the summer by George Washington Goethals

George Washington Goethals

George Washington Goethals was a United States Army officer and civil engineer, best known for his supervision of construction and the opening of the Panama Canal...

, a brilliant engineer and assistant professor who took an interest in him. (Goethals later directed construction of the Panama Canal

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

.) It was not unusual for candidates to require additional help in some subjects. Young's strength was in languages, and he learned several.

Young graduated with his commission as a second lieutenant in 1889, the third black man to do so at the time. He was first assigned to the Tenth U.S. Cavalry Regiment

U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment

The 10th Cavalry Regiment is a unit of the United States Army. Formed as a segregated African-American unit, the 10th Cavalry was one of the original "Buffalo Soldier" regiments. It served in combat during the Indian Wars in the western United States, the Spanish-American War in Cuba and in the...

. Through a reassignment, he served first with the Ninth U.S. Cavalry Regiment, serving first in Nebraska. His subsequent service of 28 years was chiefly with black troops — the Ninth U.S. Cavalry and the Tenth U.S. Cavalry

U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment

The 10th Cavalry Regiment is a unit of the United States Army. Formed as a segregated African-American unit, the 10th Cavalry was one of the original "Buffalo Soldier" regiments. It served in combat during the Indian Wars in the western United States, the Spanish-American War in Cuba and in the...

, black troops nicknamed the "Buffalo Soldiers" since the Indian Wars

Indian Wars

American Indian Wars is the name used in the United States to describe a series of conflicts between American settlers or the federal government and the native peoples of North America before and after the American Revolutionary War. The wars resulted from the arrival of European colonizers who...

. The armed services were racially segregated

Racial segregation in the United States

Racial segregation in the United States, as a general term, included the racial segregation or hypersegregation of facilities, services, and opportunities such as housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation along racial lines...

until 1948, when President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

integrated them by Executive order.

Marriage and family

After getting established in his career, Young married Ada Mills on February 18, 1904 in Oakland, CaliforniaOakland, California

Oakland is a major West Coast port city on San Francisco Bay in the U.S. state of California. It is the eighth-largest city in the state with a 2010 population of 390,724...

. They had two children: Charles Noel, born in 1906 in Ohio, and Marie Aurelia, born in 1909 when Young and his family were stationed in the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

.

Military service

Fort Duchesne, Utah

Fort Duchesne is a census-designated place in Uintah County, Utah, United States. The population was 621 at the 2000 census, a slight decrease from the 1990 figure of 655...

.

Beginning in 1894 as a lieutenant, Young was assigned to Wilberforce College

Wilberforce University

Wilberforce University is a private, coed, liberal arts historically black university located in Wilberforce, Ohio. Affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, it was the first college to be owned and operated by African Americans...

in Ohio, a historically black college (HBCU), to lead the new military sciences department, which was established under a special federal grant. As a professor for four years, he was one of a number of outstanding men on the staff, including W.E.B. Du Bois

W.E.B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, and editor. Born in Massachusetts, Du Bois attended Harvard, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate...

, with whom he became friends.

National Park assignments

In 1903, Young served as Captain of a black company at the Presidio of San FranciscoPresidio of San Francisco

The Presidio of San Francisco is a park on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula in San Francisco, California, within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area...

. When appointed acting superintendent

Management

Management in all business and organizational activities is the act of getting people together to accomplish desired goals and objectives using available resources efficiently and effectively...

of Sequoia

Sequoia National Park

Sequoia National Park is a national park in the southern Sierra Nevada east of Visalia, California, in the United States. It was established on September 25, 1890. The park spans . Encompassing a vertical relief of nearly , the park contains among its natural resources the highest point in the...

and General Grant national park

National park

A national park is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual nations designate their own national parks differently A national park is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or...

s, he was the first black superintendent of a national park. At the time the military supervised the parks. Because of limited funding, the Army assigned personnel for short-term assignments during the summers, making it difficult for the officers to accomplish longer term goals, such as construction of infrastructure. Young supervised payroll accounts

Payroll

In a company, payroll is the sum of all financial records of salaries for an employee, wages, bonuses and deductions. In accounting, payroll refers to the amount paid to employees for services they provided during a certain period of time. Payroll plays a major role in a company for several reasons...

and directed the activities of rangers

Park ranger

A park ranger or forest ranger is a person entrusted with protecting and preserving parklands – national, state, provincial, or local parks. Different countries use different names for the position. Ranger is the favored term in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Within the United...

.

Young's greatest impact on the park was managing road

Road

A road is a thoroughfare, route, or way on land between two places, which typically has been paved or otherwise improved to allow travel by some conveyance, including a horse, cart, or motor vehicle. Roads consist of one, or sometimes two, roadways each with one or more lanes and also any...

construction, which helped to improve the underdeveloped park and enable more visitors to travel within it. Young and his troops accomplished more that summer than had teams under the three military officers who had been assigned the previous three summers. Captain Young and his troops completed a wagon road to the Giant Forest, home of the world's largest trees, and a road to the base of the famous Moro Rock

Moro Rock

Moro Rock is a granite dome rock formation in Sequoia National Park, California, USA. It is located in the center of the park, at the head of Moro Creek, between Giant Forest and Crescent Meadow. A stairway, built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps, is cut into and poured onto the...

. By mid-August, wagons of visitors were able to enter the mountaintop forest for the first time.

With the end of the brief summer construction season, Young was transferred on November 2, 1903, and reassigned as the troop commander of the Tenth Cavalry at the Presidio. In his final report on Sequoia Park to the Secretary of the Interior

United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States Secretary of the Interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior.The US Department of the Interior should not be confused with the concept of Ministries of the Interior as used in other countries...

, he recommended the government

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

acquire privately held lands there, to secure more park area for future generations. This recommendation was noted in legislation to that purpose introduced in the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

.

Other military assignments

With the Army's founding of the Military Intelligence Department, in 1904 it assigned Young as one the first military attachés, serving in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. He was to collect intelligence on different groups in Haiti, to help identify forces that might destabilize the government. He served there for three years.In 1908 Young was sent to the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

to join his Ninth Regiment and command a squadron of two troops. It was his second tour there. After his return to the US, he served for two years at Fort D.A. Russell, Wyoming.

In 1912 Young was assigned as military attaché

Military attaché

A military attaché is a military expert who is attached to a diplomatic mission . This post is normally filled by a high-ranking military officer who retains the commission while serving in an embassy...

in Liberia, the first African American to hold that post. For three years, he served as an expert adviser to the Liberian Government and also took a direct role, supervising construction of the country's infrastructure. For his achievements, in 1916 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, usually abbreviated as NAACP, is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909. Its mission is "to ensure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights of all persons and to...

(NAACP) awarded Young the Spingarn Medal

Spingarn Medal

The Spingarn Medal is awarded annually by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for outstanding achievement by an African American....

, given annually to the African American demonstrating the highest achievement and contributions.

During the 1916 Punitive Expedition

Punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a state or any group of persons outside the borders of the punishing state. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong behavior, but may be also be a covered revenge...

by the United States into Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, then Major Young commanded the 2nd squadron of the 10th United States Cavalry. While leading a cavalry pistol charge against Pancho Villa

Pancho Villa

José Doroteo Arango Arámbula – better known by his pseudonym Francisco Villa or its hypocorism Pancho Villa – was one of the most prominent Mexican Revolutionary generals....

's forces at Agua Caliente (1 April 1916), he routed the opposing forces without losing a single man. His swift action saved the wounded General Beltran

Beltran

Beltran or Beltrán is a Spanish given name and surname, and may refer to:In religion:* Saint Luis Beltrán, patron saint of ColombiaIn politics:* Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán, Spanish conquistador and dictator in colonial Mexico...

and his men of the 13th Cavalry squadron, who had been outflanked.

Because of his exceptional leadership of the 10th Cavalry in the Mexican theater of war, Young was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in September 1916. He was assigned as commander of Fort Huachuca

Fort Huachuca

Fort Huachuca is a United States Army installation under the command of the United States Army Installation Management Command. It is located in Cochise County, in southeast Arizona, about north of the border with Mexico. Beginning in 1913, for 20 years the fort was the base for the "Buffalo...

, the base in Arizona

Arizona

Arizona ; is a state located in the southwestern region of the United States. It is also part of the western United States and the mountain west. The capital and largest city is Phoenix...

of the Tenth Cavalry, nicknamed the "Buffalo Soldiers", until mid 1917. He was the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel in the US Army. With the outbreak of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, Young likely hoped for a chance to gain a promotion to general. Resistance to black officers and health problems meant he never reached this goal. He was sidelined by a diagnosis of high blood pressure

Hypertension

Hypertension or high blood pressure is a cardiac chronic medical condition in which the systemic arterial blood pressure is elevated. What that means is that the heart is having to work harder than it should to pump the blood around the body. Blood pressure involves two measurements, systolic and...

, which forced him to accept a medical furlough, and was placed temporarily on the inactive list on June 22, 1917.

He returned to Wilberforce University, where he was a Professor of Military Science through most of 1918. On November 6, 1918, after Young traveled by horseback from Wilberforce, Ohio

Wilberforce, Ohio

Wilberforce is a census-designated place in Greene County, Ohio, United States. The population was 1,579 at the 2000 census. The community was named for the English statesman William Wilberforce, who worked for abolition of slavery and achieved the end of the slave trade in the United Kingdom and...

to Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

to prove his physical fitness, he was reinstated on active duty in the Army and promoted to full Colonel. In 1919, he was assigned again as military attaché to Liberia.

Young died January 8, 1922 of a kidney infection while on a reconnaissance

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance is the military term for exploring beyond the area occupied by friendly forces to gain information about enemy forces or features of the environment....

mission in Nigeria

Nigeria

Nigeria , officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a federal constitutional republic comprising 36 states and its Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The country is located in West Africa and shares land borders with the Republic of Benin in the west, Chad and Cameroon in the east, and Niger in...

. His body was returned to the United States, where he was given a full military funeral and buried at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, is a military cemetery in the United States of America, established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House, formerly the estate of the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna Lee, a great...

near Washington, DC. He had become a public and respected figure because of his unique achievements in the US Army, and his obituary was carried in the New York Times.

Honors and legacy

- 1903 - The Visalia, CaliforniaVisalia, CaliforniaVisalia is a Central California city situated in the heart of California’s agricultural San Joaquin Valley, approximately southeast of San Francisco and north of Los Angeles...

Board of Trade presented Young with a citation in appreciation of his performance as Acting Superintendent of Sequoia National Park. - 1916 - The NAACP awarded him the Spingarn Medal for his achievements in Liberia and the US Army.

- He was elected an honorary member of the Omega Psi PhiOmega Psi PhiOmega Psi Phi is a fraternity and is the first African-American national fraternal organization to be founded at a historically black college. Omega Psi Phi was founded on November 17, 1911, at Howard University in Washington, D.C.. The founders were three Howard University juniors, Edgar Amos...

fraternity. - 1922 - Young's obituary appeared in the New York Times, demonstrating his national reputation

- 1922 - His funeral was one of few held at the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National CemeteryArlington National CemeteryArlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, is a military cemetery in the United States of America, established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Arlington House, formerly the estate of the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee's wife Mary Anna Lee, a great...

, where he was buried in Section 3. - Charles E. Young Elementary School, named in his honor, was built in Washington, D.C. The school is the first elementary school in Northeast D.C., and was built explicitly to improve education in the city's black neighborhoods.

- 1974 - The houseColonel Charles Young HouseThe Colonel Charles Young house is a National Historic Landmark in Wilberforce, Ohio. A military leader, Col. Charles Young was born in 1864, the third African American graduate of West Point, first black U.S...

where he had lived when teaching at Wilberforce University was designated a National Historic LandmarkNational Historic LandmarkA National Historic Landmark is a building, site, structure, object, or district, that is officially recognized by the United States government for its historical significance...

, in recognition of his historic importance. - 2001 - Senator DeWineDeWineDeWine is the surname of three United States politicians from Ohio:* Mike DeWine, former United States Senator from Ohio* Pat DeWine, member of the Hamilton County Commission* Kevin DeWine, member of the Ohio House of Representatives...

introduced Senate Resolution 97, to recognize the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, and Colonel Charles D. Young.

This article is based in part on a document created by the National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

, which is part of the U.S. government. As such, it is presumed to be in the public domain.

Additional reading

- Infobox photograph- Chew, Abraham. A Biography of Colonel Charles Young, Washington, D.C.: R. L. Pendelton, 1923

- Greene, Robert E. Colonel Charles Young: Soldier and Diplomat, 1985

- Kilroy, David P. For Race and Country: The Life and Career of Charles Young, 2003

- Shellum, Brian G., Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point, Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2006.

- http://books.google.com/books?id=rX6t9lEDidoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Black+Officer+in+a+Buffalo+Soldier+Regiment,+The+Military+Career+of+Charles+Young&source=bl&ots=1OrJG3IzO_&sig=INa46x1k65can1v4saZ8WRjWKt0&hl=en&ei=GY0OTPmYL9WCnQe_26mvDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBkQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q&f=falseShellum, Brian G., Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment, The Military Career of Charles Young], Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

- Stovall, TaRessa. The Buffalo Soldier, Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 1997

- Stewart, T. G. Buffalo Soldiers: The Colored Regulars in the United States Army, Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2003

External links

- "Charles Young", National Park Service