Solomon P. Sharp

Encyclopedia

Solomon Porcius Sharp was attorney general of Kentucky

and a member of the United States Congress

and the Kentucky General Assembly

. His murder at the hands of Jereboam O. Beauchamp

in 1825 is referred to as the Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy or The Kentucky Tragedy.

Sharp began his political career representing Warren County

, in the Kentucky House of Representatives

. He briefly served in the War of 1812

, then returned to Kentucky and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives

in 1813. He was re-elected to a second term, though his support of a controversial bill regarding legislator salaries cost him his seat in 1816. Aligning himself with Kentucky's Debt Relief Party, he returned to the Kentucky House in 1817; in 1821, he accepted Governor John Adair

's appointment to the post of Attorney General of Kentucky. Adair's successor, Joseph Desha

, re-appointed him to this position. In 1825, Sharp resigned as attorney general to return to the Kentucky House.

In 1818, rumors surfaced that Sharp had fathered a stillborn

illegitimate child with Anna Cooke. Sharp denied the charge, and the immediate political effects were minimal. When the charges were repeated during Sharp's 1825 General Assembly campaign, he supposedly claimed that the child was a mulatto

and could not have been his. Whether Sharp actually made such a claim, or whether it was a rumor started by his political enemies, remains in doubt. Jereboam Beauchamp, who had married Cooke in 1824 , fatally stabbed Sharp in Sharp's home early on the morning of November 7, 1825. Sharp's murder became the inspiration for fictional works, most notably Edgar Allan Poe

's unfinished play Politian

and Robert Penn Warren

's World Enough and Time.

Solomon Sharp was born on August 22, 1787, at Abingdon

Solomon Sharp was born on August 22, 1787, at Abingdon

, Washington County

, Virginia

. He was the fifth child and third son of Captain Thomas and Jean (Maxwell) Sharp, a Scottish woman. Through the male line he was a great-great-grandson of John Sharp, Archbishop of York

. Thomas Sharp was a veteran of the Revolutionary War

, participating in the Battle of King's Mountain. The family briefly moved to the area near Nashville, Tennessee

, before settling permanently at Russellville

, Logan County

, Kentucky

, around 1795.

Sharp "[intermittently attended] one of Logan County's academies" during his childhood years; the schools of Logan County were primitive then. Nevertheless, he studied law in some capacity, and was admitted to the bar

in 1806. He opened a practice in Russellville, but soon relocated to Bowling Green

where he engaged in land speculation

, sometimes in partnership with his brother, Dr. Leander Sharp.

On December 17, 1818, Sharp married Eliza T. Scott; the union produced three children. He moved the family to Frankfort, Kentucky

, in 1820. In May or June 1820, a woman named Anna Cooke claimed Sharp was the father of her stillborn illegitimate child; Sharp denied this claim. Because of the child's dark skin tone, some speculated that the child was a mulatto

. The scandal soon abated, and although Sharp's political opponents would continue to call attention to it, his reputation remained largely untarnished.

in the Kentucky House of Representatives

. During his tenure, he supported the election of Henry Clay

to the U.S. Senate

, the creation of a state lottery, and the creation of an academy in Barren County

. He served on a number of committees, and for a time, served as interim speaker of the house during the General Assembly's second session. He was re-elected in 1810 and 1811. During the 1811 session, he worked with Ben Hardin

to secure passage of a bill to ensure that state officers and attorneys at law would not be involved in duel

ing. He also opposed a measure allowing harsher treatment of slaves.

Sharp's political service was interrupted by the War of 1812

. On September 18, 1812, he enlisted as a private

in the Kentucky militia

, serving under Lieutenant Colonel

Young Ewing. Twelve days later, he was promoted to major

and made a part of Ewing's staff. Ewing's unit was put under the command of general Samuel Hopkins

during his ineffective expedition against the Shawnee

. In total, the expedition lasted only forty-two days and never actually engaged the enemy. Sharp recognized the value of a record of military service in Kentucky politics, however, and he eventually was promoted to the rank of captain and later, colonel, although sources do not explain when or why this happened.

as a member of the United States House of Representatives

. Aligning himself with the War Hawks, he defended President

James Madison

's decision to lead the country into the war, and supported a proposal to offer 100 acre (0.156250138152179 sq mi; 0.404686 km²) of land to any British

deserters

. Sharp also "[passionately denounced] Federalist obstruction of the war effort". In a speech on April 8, 1813, he opposed indemnity

for those defrauded in the Yazoo land scandal

. He allied himself with South Carolina

's John C. Calhoun

in supporting the Second Bank of the United States

.

Sharp was re-elected to the Fourteenth Congress

, during which he served as chairman of the Committee on Private Land Claims

. He supported the controversial Compensation Act of 1816 sponsored by fellow Kentuckian Richard Mentor Johnson

. The measure, which paid Congressmen a flat salary instead of paying them only for the days when they were in session, was unpopular with the voters of his district. When the next congressional session opened in December 1816, Sharp reversed his position and voted to repeal the law, but the damage was already done; he lost his seat in the House in the next election.

In 1817, Sharp was again elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives. During his term, he supported measures for internal improvements

, but opposed the creation of a state health board and a proposal to open the state's vacant lands to the widows and orphans of soldiers killed in the War of 1812. Most notably, however, he supported the creation of 46 new banks in the state, and proposed a tax on the branches of the Bank of the United States in Lexington

and Louisville

.

. His opponent, John Upshaw Waring, was a notably violent and malicious man. Waring sent two threatening letters to Sharp, and on June 18, 1821, published a handbill attacking Sharp's character. Five days later, Sharp ceased campaigning for the senatorial seat and accepted the appointment of Governor John Adair

to the position of attorney general of Kentucky

. Sharp's nomination was unanimously confirmed on October 30, 1821.

Sharp took office at a critical time Kentucky's history. Still reeling from the financial Panic of 1819

, state politicians had split into two camps: those who supported legislation favorable to debtors (the Debt Relief Party) and those who favored the protection of creditors (typically called Anti-Reliefers.) Sharp had identified himself with the Relief Party, as had Governor Adair.

In the 1824 presidential election

, Sharp alienated some of his constituency by supporting his old House colleague John C. Calhoun instead of Kentucky's favorite son, Henry Clay

. When it was clear that Calhoun's bid would fail, Sharp threw his support behind Andrew Jackson

. He served as secretary of a meeting of Jackson supporters in Frankfort on October 2, 1824.

Governor Adair's term expired in 1825, and he was succeeded by another Relief Party member, General Joseph Desha

. Desha and Sharp had been colleagues in Congress, and Desha re-appointed Sharp as attorney general. The Relief faction in the legislature managed to pass several measures favorable to debtors, but the Kentucky Court of Appeals

struck them down as unconstitutional. Unable to muster the votes to remove the hostile justices on the Court of Appeals, Relief partisans in the General Assembly passed legislation to abolish the entire court and create a new one, which Governor Desha promptly stocked with sympathetic judges. For a time, two courts claimed authority as Kentucky's court of last resort; this period was referred to as the Old Court-New Court controversy

.

Sharp's role in the Relief Party's plan to abolish the old court and replace it with a new, more favorable court is not explicitly known, but as the administration's chief legal counsel, it is assumed he was heavily involved. He personally issued the order for Old Court clerk Achilles Sneed to turn over his records to New Court clerk Francis P. Blair. He also lent a measure of legitimacy to the New Court by practicing as attorney general before the New Court to the exclusion of the Old Court.

On May 11, 1825, Sharp was charged with welcoming the Marquis de Lafayette

to Kentucky on behalf of the Desha administration. At a banquet in Lafayette's honor three days later, Sharp toasted the guest of honor: "The People: Liberty will always be safe in their holy keeping." Shortly following this event, Sharp resigned as attorney general, likely because Relief Party advocates felt he would be more useful in the General Assembly.

The Anti-Relief partisans nominated former Senator

John J. Crittenden

for one of the two seats apportioned to Franklin County

in the state House. The Relief Party countered with Sharp and Lewis Sanders, a prominent area lawyer. During the campaign, the charges of Sharp's illegitimate child resurfaced. It was alleged that Sharp made the claim that the child was mulatto and could not have been his; whether Sharp actually made this claim may never be known for certain. Despite the controversy, Sharp netted the most votes in the election, receiving 69 more than Crittenden, who captured the second seat.

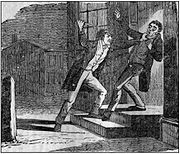

In the early hours of November 7, 1825, the day the General Assembly was to open its session, an assassin knocked on the door of Sharp's residence. When Sharp answered the door, the assassin grabbed him with his left hand and used his right to stab him in the heart with a poisoned dagger. Sharp died at approximately two o'clock in the morning. After lying in state

In the early hours of November 7, 1825, the day the General Assembly was to open its session, an assassin knocked on the door of Sharp's residence. When Sharp answered the door, the assassin grabbed him with his left hand and used his right to stab him in the heart with a poisoned dagger. Sharp died at approximately two o'clock in the morning. After lying in state

in the House of Representatives Hall, he was buried in Frankfort Cemetery

.

Because of the timing of the assassination, speculation mounted that Sharp had been killed by an Anti-Relief partisan. Sharp's political rival, John J. Crittenden, attempted to blunt these accusations by personally introducing a resolution condemning the murder and offering a $3000 reward for the capture of the assassin. The trustees of the city of Frankfort added a reward of $1000, and an additional $2000 reward was raised from private sources. In the 1825 session of the General Assembly, a measure to form Sharp County from Muhlenberg County

died on the floor due to the tumultuous politics of the session.

In the investigation that followed, the evidence quickly pointed to Jereboam Beauchamp, who had married Anna Cooke in 1824, as the assassin. On November 11, 1825, a four-man posse

arrested Beauchamp at his home in Franklin, Kentucky

. He was tried and convicted of Sharp's murder on May 19, 1826. His sentence – execution by hanging – was to be carried out on June 16, 1826. He requested a stay of execution

so that he could write a justification of his actions. The request was granted, allowing Beauchamp to complete his book, The confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp: who was hanged at Frankfort, Ky., on the 7th day of July, 1826, for the murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. After two failed suicide attempt

s, Beauchamp was hanged for his crime on July 7, 1826.

Beauchamp's Confession was published in 1826. Some editions included The Letters of Ann Cook as an appendix, although historians dispute whether Cooke was actually their author. The following year, Sharp's brother, Dr. Leander Sharp, wrote Vindication of the character of the late Col. Solomon P. Sharp to defend him from the charges contained in Beauchamp's confession. In Vindication, Dr. Sharp portrayed the killing as a political assassination: he named Patrick Darby, a partisan of the Anti-Relief faction, as co-conspirator with Beauchamp, also an Anti-Relief stalwart. Darby threatened to sue Sharp if he published his Vindication; Waring threatened to kill him. Heeding these threats, Sharp did not publish his work; all extant manuscripts remained in his house, where they were discovered during a remodeling many years later.

Attorney General of Kentucky

The Attorney General of Kentucky is an office created by the Kentucky Constitution. . Under Kentucky law, he serves several roles, including the state's chief prosecutor , the state's chief law enforcement officer , and the state's chief law officer...

and a member of the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

and the Kentucky General Assembly

Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky.The General Assembly meets annually in the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky, convening on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January...

. His murder at the hands of Jereboam O. Beauchamp

Jereboam O. Beauchamp

Jereboam Orville Beauchamp was an American lawyer who murdered the Kentucky legislator Solomon P. Sharp, an event known as the Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy. In 1821, Sharp was accused of fathering the illegitimate stillborn child of a woman named Anna Cooke. Sharp denied paternity of the child, and...

in 1825 is referred to as the Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy or The Kentucky Tragedy.

Sharp began his political career representing Warren County

Warren County, Kentucky

Warren County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky, specifically the Pennyroyal Plateau and Western Coal Fields regions. It is included in the Bowling Green, Kentucky, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 113,792 in the 2010 Census. The county seat is Bowling Green...

, in the Kentucky House of Representatives

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a House district, except when necessary to preserve...

. He briefly served in the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

, then returned to Kentucky and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

in 1813. He was re-elected to a second term, though his support of a controversial bill regarding legislator salaries cost him his seat in 1816. Aligning himself with Kentucky's Debt Relief Party, he returned to the Kentucky House in 1817; in 1821, he accepted Governor John Adair

John Adair

John Adair was an American pioneer, soldier and statesman. He was the eighth Governor of Kentucky and represented the state in both the U.S. House and Senate. Adair enlisted in the state militia and served in the Revolutionary War, where he was held captive by the British for a period of time...

's appointment to the post of Attorney General of Kentucky. Adair's successor, Joseph Desha

Joseph Desha

Joseph Desha was a U.S. Representative and the ninth Governor of Kentucky. Desha was the first Kentucky governor not to have served in the Revolutionary War. He did, however, serve under William Henry Harrison and "Mad" Anthony Wayne in the Northwest Indian War, and lost two brothers in battle...

, re-appointed him to this position. In 1825, Sharp resigned as attorney general to return to the Kentucky House.

In 1818, rumors surfaced that Sharp had fathered a stillborn

Stillbirth

A stillbirth occurs when a fetus has died in the uterus. The Australian definition specifies that fetal death is termed a stillbirth after 20 weeks gestation or the fetus weighs more than . Once the fetus has died the mother still has contractions and remains undelivered. The term is often used in...

illegitimate child with Anna Cooke. Sharp denied the charge, and the immediate political effects were minimal. When the charges were repeated during Sharp's 1825 General Assembly campaign, he supposedly claimed that the child was a mulatto

Mulatto

Mulatto denotes a person with one white parent and one black parent, or more broadly, a person of mixed black and white ancestry. Contemporary usage of the term varies greatly, and the broader sense of the term makes its application rather subjective, as not all people of mixed white and black...

and could not have been his. Whether Sharp actually made such a claim, or whether it was a rumor started by his political enemies, remains in doubt. Jereboam Beauchamp, who had married Cooke in 1824 , fatally stabbed Sharp in Sharp's home early on the morning of November 7, 1825. Sharp's murder became the inspiration for fictional works, most notably Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective...

's unfinished play Politian

Politian (play)

Politian is the only play known to have been written by Edgar Allan Poe, composed in 1835 but never completed.The play is a fictionalized version of a true event in Kentucky: the murder of Solomon P. Sharp by Jereboam O. Beauchamp in 1825. The so-called "Kentucky Tragedy" became a national...

and Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren was an American poet, novelist, and literary critic and was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. He founded the influential literary journal The Southern Review with Cleanth Brooks in 1935...

's World Enough and Time.

Personal life

Abingdon, Virginia

Abingdon is a town in Washington County, Virginia, USA, 133 miles southwest of Roanoke. The population was 8,191 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Washington County and is a designated Virginia Historic Landmark...

, Washington County

Washington County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 51,103 people, 21,056 households, and 14,949 families residing in the county. The population density was 91 people per square mile . There were 22,985 housing units at an average density of 41 per square mile...

, Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

. He was the fifth child and third son of Captain Thomas and Jean (Maxwell) Sharp, a Scottish woman. Through the male line he was a great-great-grandson of John Sharp, Archbishop of York

John Sharp, Archbishop of York

John Sharp , English divine, Archbishop of York, was born at Bradford, and educated at Christ's College, Cambridge.-Biography:...

. Thomas Sharp was a veteran of the Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

, participating in the Battle of King's Mountain. The family briefly moved to the area near Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat of Davidson County. It is located on the Cumberland River in Davidson County, in the north-central part of the state. The city is a center for the health care, publishing, banking and transportation industries, and is home...

, before settling permanently at Russellville

Russellville, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 7,149 people, 3,064 households, and 1,973 families residing in the city. The population density was 672.1 people per square mile . There were 3,458 housing units at an average density of 325.1 per square mile...

, Logan County

Logan County, Kentucky

Logan County is a county located in the southwest area of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2000, the population was 26,573. Its county seat is Russellville...

, Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, around 1795.

Sharp "[intermittently attended] one of Logan County's academies" during his childhood years; the schools of Logan County were primitive then. Nevertheless, he studied law in some capacity, and was admitted to the bar

Bar (law)

Bar in a legal context has three possible meanings: the division of a courtroom between its working and public areas; the process of qualifying to practice law; and the legal profession.-Courtroom division:...

in 1806. He opened a practice in Russellville, but soon relocated to Bowling Green

Bowling Green, Kentucky

Bowling Green is the third-most populous city in the state of Kentucky after Louisville and Lexington, with a population of 58,067 as of the 2010 Census. It is the county seat of Warren County and the principal city of the Bowling Green, Kentucky Metropolitan Statistical Area with an estimated 2009...

where he engaged in land speculation

Speculation

In finance, speculation is a financial action that does not promise safety of the initial investment along with the return on the principal sum...

, sometimes in partnership with his brother, Dr. Leander Sharp.

On December 17, 1818, Sharp married Eliza T. Scott; the union produced three children. He moved the family to Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort, Kentucky

Frankfort is a city in Kentucky that serves as the state capital and the county seat of Franklin County. The population was 27,741 at the 2000 census; by population it is the 5th smallest state capital in the United States...

, in 1820. In May or June 1820, a woman named Anna Cooke claimed Sharp was the father of her stillborn illegitimate child; Sharp denied this claim. Because of the child's dark skin tone, some speculated that the child was a mulatto

Mulatto

Mulatto denotes a person with one white parent and one black parent, or more broadly, a person of mixed black and white ancestry. Contemporary usage of the term varies greatly, and the broader sense of the term makes its application rather subjective, as not all people of mixed white and black...

. The scandal soon abated, and although Sharp's political opponents would continue to call attention to it, his reputation remained largely untarnished.

Political career

Sharp's first political office came in 1809, when he was elected to represent Warren CountyWarren County, Kentucky

Warren County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky, specifically the Pennyroyal Plateau and Western Coal Fields regions. It is included in the Bowling Green, Kentucky, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 113,792 in the 2010 Census. The county seat is Bowling Green...

in the Kentucky House of Representatives

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a House district, except when necessary to preserve...

. During his tenure, he supported the election of Henry Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

to the U.S. Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

, the creation of a state lottery, and the creation of an academy in Barren County

Barren County, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 38,033 people, 15,346 households, and 10,941 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 17,095 housing units at an average density of...

. He served on a number of committees, and for a time, served as interim speaker of the house during the General Assembly's second session. He was re-elected in 1810 and 1811. During the 1811 session, he worked with Ben Hardin

Benjamin Hardin

Benjamin Hardin was a United States Representative from Kentucky. Martin Davis Hardin was his cousin. He was born at the Georges Creek settlement on the Monongahela River, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania and then moved with his parents to Washington County, Kentucky in 1788...

to secure passage of a bill to ensure that state officers and attorneys at law would not be involved in duel

Duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two individuals, with matched weapons in accordance with agreed-upon rules.Duels in this form were chiefly practised in Early Modern Europe, with precedents in the medieval code of chivalry, and continued into the modern period especially among...

ing. He also opposed a measure allowing harsher treatment of slaves.

Sharp's political service was interrupted by the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

. On September 18, 1812, he enlisted as a private

Private (rank)

A Private is a soldier of the lowest military rank .In modern military parlance, 'Private' is shortened to 'Pte' in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries and to 'Pvt.' in the United States.Notably both Sir Fitzroy MacLean and Enoch Powell are examples of, rare, rapid career...

in the Kentucky militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

, serving under Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel is a rank of commissioned officer in the armies and most marine forces and some air forces of the world, typically ranking above a major and below a colonel. The rank of lieutenant colonel is often shortened to simply "colonel" in conversation and in unofficial correspondence...

Young Ewing. Twelve days later, he was promoted to major

Major

Major is a rank of commissioned officer, with corresponding ranks existing in almost every military in the world.When used unhyphenated, in conjunction with no other indicator of rank, the term refers to the rank just senior to that of an Army captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

and made a part of Ewing's staff. Ewing's unit was put under the command of general Samuel Hopkins

Samuel Hopkins (congressman)

Samuel Hopkins was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky.Born in Albemarle County, Virginia, Hopkins was educated by private tutors...

during his ineffective expedition against the Shawnee

Shawnee

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki, are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania...

. In total, the expedition lasted only forty-two days and never actually engaged the enemy. Sharp recognized the value of a record of military service in Kentucky politics, however, and he eventually was promoted to the rank of captain and later, colonel, although sources do not explain when or why this happened.

U.S. Representative

In 1812, Sharp was elected to the Thirteenth Congress13th United States Congress

- Senate :* President: Elbridge Gerry , until November 23, 1814, thereafter vacant.* President pro tempore: Joseph B. Varnum , December 6, 1813 – February 3, 1814** John Gaillard , elected November 25, 1814- House of Representatives :...

as a member of the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

. Aligning himself with the War Hawks, he defended President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

's decision to lead the country into the war, and supported a proposal to offer 100 acre (0.156250138152179 sq mi; 0.404686 km²) of land to any British

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

deserters

Desertion

In military terminology, desertion is the abandonment of a "duty" or post without permission and is done with the intention of not returning...

. Sharp also "[passionately denounced] Federalist obstruction of the war effort". In a speech on April 8, 1813, he opposed indemnity

Indemnity

An indemnity is a sum paid by A to B by way of compensation for a particular loss suffered by B. The indemnitor may or may not be responsible for the loss suffered by the indemnitee...

for those defrauded in the Yazoo land scandal

Yazoo land scandal

The Yazoo land scandal, Yazoo fraud, Yazoo land fraud, or Yazoo land controversy was a massive fraud perpetrated from 1794 to 1803 by several Georgia governors and the state legislature. They sold large tracts of land in what is now the state of Mississippi to political insiders at very low prices...

. He allied himself with South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

's John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

in supporting the Second Bank of the United States

Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816, five years after the First Bank of the United States lost its own charter. The Second Bank of the United States was initially headquartered in Carpenters' Hall, Philadelphia, the same as the First Bank, and had branches throughout the...

.

Sharp was re-elected to the Fourteenth Congress

14th United States Congress

- Senate :* President: Vacant* President pro tempore: John Gaillard of South Carolina, first elected December 4, 1815- House of Representatives :* Speaker: Henry Clay of Kentucky-Members:This list is arranged by chamber, then by state...

, during which he served as chairman of the Committee on Private Land Claims

United States Court of Private Land Claims

The United States Court of Private Land Claims , was a United States court created to decide land claims guaranteed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in the territories of New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah, and in the states of Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming.-Origins:During Spanish and Mexican rule...

. He supported the controversial Compensation Act of 1816 sponsored by fellow Kentuckian Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson was the ninth Vice President of the United States, serving in the administration of Martin Van Buren . He was the only vice-president ever elected by the United States Senate under the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment. Johnson also represented Kentucky in the U.S...

. The measure, which paid Congressmen a flat salary instead of paying them only for the days when they were in session, was unpopular with the voters of his district. When the next congressional session opened in December 1816, Sharp reversed his position and voted to repeal the law, but the damage was already done; he lost his seat in the House in the next election.

In 1817, Sharp was again elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives. During his term, he supported measures for internal improvements

Internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canals, harbors and navigation improvements...

, but opposed the creation of a state health board and a proposal to open the state's vacant lands to the widows and orphans of soldiers killed in the War of 1812. Most notably, however, he supported the creation of 46 new banks in the state, and proposed a tax on the branches of the Bank of the United States in Lexington

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

and Louisville

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

.

Attorney general of Kentucky

In 1821, Sharp began a campaign for a seat in the Kentucky SenateKentucky Senate

The Kentucky Senate is the upper house of the Kentucky General Assembly. The Kentucky Senate is composed of 38 members elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. There are no term limits for Kentucky Senators...

. His opponent, John Upshaw Waring, was a notably violent and malicious man. Waring sent two threatening letters to Sharp, and on June 18, 1821, published a handbill attacking Sharp's character. Five days later, Sharp ceased campaigning for the senatorial seat and accepted the appointment of Governor John Adair

John Adair

John Adair was an American pioneer, soldier and statesman. He was the eighth Governor of Kentucky and represented the state in both the U.S. House and Senate. Adair enlisted in the state militia and served in the Revolutionary War, where he was held captive by the British for a period of time...

to the position of attorney general of Kentucky

Attorney General of Kentucky

The Attorney General of Kentucky is an office created by the Kentucky Constitution. . Under Kentucky law, he serves several roles, including the state's chief prosecutor , the state's chief law enforcement officer , and the state's chief law officer...

. Sharp's nomination was unanimously confirmed on October 30, 1821.

Sharp took office at a critical time Kentucky's history. Still reeling from the financial Panic of 1819

Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first major financial crisis in the United States, and had occurred during the political calm of the Era of Good Feelings. The new nation previously had faced a depression following the war of independence in the late 1780s and led directly to the establishment of the...

, state politicians had split into two camps: those who supported legislation favorable to debtors (the Debt Relief Party) and those who favored the protection of creditors (typically called Anti-Reliefers.) Sharp had identified himself with the Relief Party, as had Governor Adair.

In the 1824 presidential election

United States presidential election, 1824

In the United States presidential election of 1824, John Quincy Adams was elected President on February 9, 1825, after the election was decided by the House of Representatives. The previous years had seen a one-party government in the United States, as the Federalist Party had dissolved, leaving...

, Sharp alienated some of his constituency by supporting his old House colleague John C. Calhoun instead of Kentucky's favorite son, Henry Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

. When it was clear that Calhoun's bid would fail, Sharp threw his support behind Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

. He served as secretary of a meeting of Jackson supporters in Frankfort on October 2, 1824.

Governor Adair's term expired in 1825, and he was succeeded by another Relief Party member, General Joseph Desha

Joseph Desha

Joseph Desha was a U.S. Representative and the ninth Governor of Kentucky. Desha was the first Kentucky governor not to have served in the Revolutionary War. He did, however, serve under William Henry Harrison and "Mad" Anthony Wayne in the Northwest Indian War, and lost two brothers in battle...

. Desha and Sharp had been colleagues in Congress, and Desha re-appointed Sharp as attorney general. The Relief faction in the legislature managed to pass several measures favorable to debtors, but the Kentucky Court of Appeals

Kentucky Court of Appeals

The Kentucky Court of Appeals is the lower of Kentucky's two appellate courts, under the Kentucky Supreme Court. Prior to a 1975 amendment to the Kentucky Constitution the Kentucky Court of Appeals was the only appellate court in Kentucky....

struck them down as unconstitutional. Unable to muster the votes to remove the hostile justices on the Court of Appeals, Relief partisans in the General Assembly passed legislation to abolish the entire court and create a new one, which Governor Desha promptly stocked with sympathetic judges. For a time, two courts claimed authority as Kentucky's court of last resort; this period was referred to as the Old Court-New Court controversy

Old Court-New Court controversy

The Old Court – New Court controversy was a 19th century political controversy in the U.S. state of Kentucky in which the Kentucky General Assembly abolished the Kentucky Court of Appeals and replaced it with a new court...

.

Sharp's role in the Relief Party's plan to abolish the old court and replace it with a new, more favorable court is not explicitly known, but as the administration's chief legal counsel, it is assumed he was heavily involved. He personally issued the order for Old Court clerk Achilles Sneed to turn over his records to New Court clerk Francis P. Blair. He also lent a measure of legitimacy to the New Court by practicing as attorney general before the New Court to the exclusion of the Old Court.

On May 11, 1825, Sharp was charged with welcoming the Marquis de Lafayette

Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette , often known as simply Lafayette, was a French aristocrat and military officer born in Chavaniac, in the province of Auvergne in south central France...

to Kentucky on behalf of the Desha administration. At a banquet in Lafayette's honor three days later, Sharp toasted the guest of honor: "The People: Liberty will always be safe in their holy keeping." Shortly following this event, Sharp resigned as attorney general, likely because Relief Party advocates felt he would be more useful in the General Assembly.

The Anti-Relief partisans nominated former Senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

John J. Crittenden

John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden was a politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as United States Attorney General in the administrations of William Henry Harrison and Millard Fillmore...

for one of the two seats apportioned to Franklin County

Franklin County, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 47,687 people, 19,907 households, and 12,840 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 21,409 housing units at an average density of...

in the state House. The Relief Party countered with Sharp and Lewis Sanders, a prominent area lawyer. During the campaign, the charges of Sharp's illegitimate child resurfaced. It was alleged that Sharp made the claim that the child was mulatto and could not have been his; whether Sharp actually made this claim may never be known for certain. Despite the controversy, Sharp netted the most votes in the election, receiving 69 more than Crittenden, who captured the second seat.

Assassination and aftermath

Lying in state

Lying in state is a term used to describe the tradition in which a coffin is placed on view to allow the public at large to pay their respects to the deceased. It traditionally takes place in the principal government building of a country or city...

in the House of Representatives Hall, he was buried in Frankfort Cemetery

Frankfort Cemetery

The Frankfort Cemetery is located on East Main Street in Frankfort, Kentucky. The cemetery is the burial site of Daniel Boone and contains the graves of other famous Americans including seventeen Kentucky governors.-History:...

.

Because of the timing of the assassination, speculation mounted that Sharp had been killed by an Anti-Relief partisan. Sharp's political rival, John J. Crittenden, attempted to blunt these accusations by personally introducing a resolution condemning the murder and offering a $3000 reward for the capture of the assassin. The trustees of the city of Frankfort added a reward of $1000, and an additional $2000 reward was raised from private sources. In the 1825 session of the General Assembly, a measure to form Sharp County from Muhlenberg County

Muhlenberg County, Kentucky

Muhlenberg County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2010 Census, the population was 31,499. The county is named for Peter Muhlenberg. Its county seat is Greenville....

died on the floor due to the tumultuous politics of the session.

In the investigation that followed, the evidence quickly pointed to Jereboam Beauchamp, who had married Anna Cooke in 1824, as the assassin. On November 11, 1825, a four-man posse

Posse comitatus (common law)

Posse comitatus or sheriff's posse is the common-law or statute law authority of a county sheriff or other law officer to conscript any able-bodied males to assist him in keeping the peace or to pursue and arrest a felon, similar to the concept of the "hue and cry"...

arrested Beauchamp at his home in Franklin, Kentucky

Franklin, Kentucky

As of the census of 2000, there were 7,996 people, 3,251 households, and 2,174 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,074.7 people per square mile . There were 3,609 housing units at an average density of 485.1 per square mile...

. He was tried and convicted of Sharp's murder on May 19, 1826. His sentence – execution by hanging – was to be carried out on June 16, 1826. He requested a stay of execution

Stay of execution

A stay of execution is a court order to temporarily suspend the execution of a court judgment or other court order. The word "execution" does not necessarily mean the death penalty; it refers to the imposition of whatever judgment is being stayed....

so that he could write a justification of his actions. The request was granted, allowing Beauchamp to complete his book, The confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp: who was hanged at Frankfort, Ky., on the 7th day of July, 1826, for the murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. After two failed suicide attempt

Failed suicide attempt

Failed suicide attempts comprise a large portion of suicide attempts. Some are regarded as not true attempts at all, but rather parasuicide. The usual attempt may be a wish to affect another person by the behaviour. Consequently, it occurs in a social context and may represent a request for help....

s, Beauchamp was hanged for his crime on July 7, 1826.

Beauchamp's Confession was published in 1826. Some editions included The Letters of Ann Cook as an appendix, although historians dispute whether Cooke was actually their author. The following year, Sharp's brother, Dr. Leander Sharp, wrote Vindication of the character of the late Col. Solomon P. Sharp to defend him from the charges contained in Beauchamp's confession. In Vindication, Dr. Sharp portrayed the killing as a political assassination: he named Patrick Darby, a partisan of the Anti-Relief faction, as co-conspirator with Beauchamp, also an Anti-Relief stalwart. Darby threatened to sue Sharp if he published his Vindication; Waring threatened to kill him. Heeding these threats, Sharp did not publish his work; all extant manuscripts remained in his house, where they were discovered during a remodeling many years later.