Freeman Field Mutiny

Encyclopedia

Freeman Army Airfield

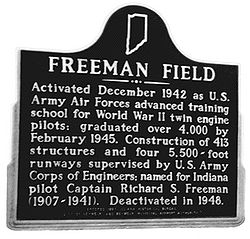

Freeman Army Airfield is an inactive United States Army Air Force base. It is located south-southwest of Seymour, Indiana.The base was established in 1942 as a pilot training airfield. It was also the first military helicopter pilot training airfield...

, a United States Army Air Forces

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces was the military aviation arm of the United States of America during and immediately after World War II, and the direct predecessor of the United States Air Force....

base near Seymour, Indiana

Seymour, Indiana

Seymour was the site of the World's First Train Robbery, committed by the local Reno Gang, on October 6, 1866 just east of town. The gang was put into prison for the robbery, and later hanged at Hangman's Crossing outside of town....

, in 1945 in which African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

members of the 477th Bombardment Group attempted to integrate

Racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration includes desegregation . In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity regardless of race, and the development of a culture that draws on diverse traditions, rather than merely...

an all-white officers' club. The mutiny resulted in 162 separate arrests of black officers, some of them twice. Three were court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

ed on relatively minor charges. One was convicted. In 1995, the Air Force

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the American uniformed services. Initially part of the United States Army, the USAF was formed as a separate branch of the military on September 18, 1947 under the National Security Act of...

officially vindicated the actions of the African-American officers, set aside the single court-martial conviction and removed letters of reprimand from the permanent files of 15 of the officers. The mutiny is generally regarded by historians of the Civil Rights Movement

Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a worldwide political movement for equality before the law occurring between approximately 1950 and 1980. In many situations it took the form of campaigns of civil resistance aimed at achieving change by nonviolent forms of resistance. In some situations it was...

as an important step toward full integration of the armed forces and as a model for later efforts to integrate public facilities through civil disobedience

Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government, or of an occupying international power. Civil disobedience is commonly, though not always, defined as being nonviolent resistance. It is one form of civil resistance...

.

The Tuskegee Airmen

Before and during World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the armed forces of the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, like much of American society, were segregated

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

by race. Historically, most African-American soldiers and sailors were relegated to support functions rather than combat

Combat

Combat, or fighting, is a purposeful violent conflict meant to establish dominance over the opposition, or to terminate the opposition forever, or drive the opposition away from a location where it is not wanted or needed....

roles, with few opportunities to advance to command

Command (military formation)

A command in military terminology is an organisational unit that the individual in Military command has responsibility for. A Commander will normally be specifically appointed into the role in order to provide a legal framework for the authority bestowed...

positions.

In 1940, in response to pressure from prominent African-American leaders such as A. Philip Randolph

A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph was a leader in the African American civil-rights movement and the American labor movement. He organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly Negro labor union. In the early civil-rights movement, Randolph led the March on Washington...

and Walter White

Walter Francis White

Walter Francis White was a civil rights activist who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for almost a quarter of a century and directed a broad program of legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement. He was also a journalist, novelist, and essayist...

, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

opened the United States Army Air Corps

United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps was a forerunner of the United States Air Force. Renamed from the Air Service on 2 July 1926, it was part of the United States Army and the predecessor of the United States Army Air Forces , established in 1941...

(after 1941, the United States Army Air Forces

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces was the military aviation arm of the United States of America during and immediately after World War II, and the direct predecessor of the United States Air Force....

) to black men who volunteered to train as fighter

Fighter aircraft

A fighter aircraft is a military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat with other aircraft, as opposed to a bomber, which is designed primarily to attack ground targets...

pilots

Aviator

An aviator is a person who flies an aircraft. The first recorded use of the term was in 1887, as a variation of 'aviation', from the Latin avis , coined in 1863 by G. de la Landelle in Aviation Ou Navigation Aérienne...

. The first of the black units, the 99th Fighter Squadron, trained at an airfield

Airport

An airport is a location where aircraft such as fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, and blimps take off and land. Aircraft may be stored or maintained at an airport...

in Tuskegee, Alabama

Tuskegee, Alabama

Tuskegee is a city in Macon County, Alabama, United States. At the 2000 census the population was 11,846 and is designated a Micropolitan Statistical Area. Tuskegee has been an important site in various stages of African American history....

, which gave rise to the name "Tuskegee Airmen

Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen is the popular name of a group of African American pilots who fought in World War II. Formally, they were the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the U.S. Army Air Corps....

" as a blanket term for the Army's black aviators. Under the command of Colonel

Colonel

Colonel , abbreviated Col or COL, is a military rank of a senior commissioned officer. It or a corresponding rank exists in most armies and in many air forces; the naval equivalent rank is generally "Captain". It is also used in some police forces and other paramilitary rank structures...

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.

Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr. was an American born United States Air Force general and commander of the World War II Tuskegee Airmen....

, the first African American to fly solo as an officer, the 99th saw action in North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

and Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

in 1943. In 1944, the 99th was merged with three other black squadrons to form the 332d Fighter Group.

Origin of the 477th Bombardment Group (M)

Continued pressure from African-American civilian leaders led the Army to let blacks train as members of bomberBomber

A bomber is a military aircraft designed to attack ground and sea targets, by dropping bombs on them, or – in recent years – by launching cruise missiles at them.-Classifications of bombers:...

crews, a step that opened many more skilled combat roles to them. On January 15, 1944, the Army re-activated the 477th Bombardment Group (Medium) to train African-American aviators to fly the B-25J Mitchell twin-engine medium bomber in combat.

Under the command of Colonel Robert R. Selway, Jr., a white officer, the 477th began training at Selfridge Field

Selfridge Field

Selfridge Air National Guard Base or Selfridge ANGB is an Air National Guard installation located in Harrison Township, Michigan, near Mount Clemens.-Units and organizations:...

near Detroit, Michigan

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit is the major city among the primary cultural, financial, and transportation centers in the Metro Detroit area, a region of 5.2 million people. As the seat of Wayne County, the city of Detroit is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan and serves as a major port on the Detroit River...

. Although the 477th had an authorized strength of 270 officer crew members, only 175 were initially assigned to Selfridge, a circumstance that led many of the black trainees to believe that the Army did not want the unit to advance to full combat readiness. However, it should also be said that all new air groups activated during World War II began with a core cadre of officers around whom the entire group was subsequently built.

The 477th also suffered from morale

Morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps when discussing the morale of a group, is an intangible term used to describe the capacity of people to maintain belief in an institution or a goal, or even in oneself and others...

problems stemming from segregation at Selfridge. Colonel Selway's superior, Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

Frank O’Driscoll Hunter http://www.wwiaviation.com/aces/ace_Hunter.shtml, commander of the First Air Force

First Air Force

The First Air Force is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Air Combat Command . It is headquartered at Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida....

, insisted on strict social segregation of black and white officers. Although Army Regulation 210-10, Paragraph 19, prohibited any public building on a military installation from being used "for the accommodation of any self-constituted special or exclusive group," thereby requiring officers' clubs be open to all officers regardless of race, the club at Selfridge was closed to black officers, a situation that led to an official War Department

United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department , was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army...

reprimand being issued to the Selfridge base commander, Colonel William Boyd.

Relocation of the 477th to Kentucky

On May 5, 1944, possibly out of fear of a repeat of the previous summer's race riotDetroit Race Riot (1943)

The Detroit Race Riot broke out in Detroit, Michigan in June 1943 and lasted for three days before Federal troops restored order. The rioting between blacks and whites began on Belle Isle on 20 June 1943 and continued until 22 June, killing 34, wounding 433, and destroying property valued at $2...

in nearby Detroit, the 477th was abruptly relocated to Godman Field at Fort Knox

Fort Knox

Fort Knox is a United States Army post in Kentucky south of Louisville and north of Elizabethtown. The base covers parts of Bullitt, Hardin, and Meade counties. It currently holds the Army Human Resources Center of Excellence to include the Army Human Resources Command, United States Army Cadet...

in Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

. Godman's only officers' club was open to blacks, but white officers used the club at Fort Knox on a "guest membership" basis. The morale of the 477th remained poor because the field was not suited to use by the B-25 and because black officers, including combat veterans of the 332nd Fighter Group who had transferred to the bomber unit, were not being advanced to command positions. By early 1945, however, the 477th reached its full combat strength: the 616th Bombardment Squadron

616th Bombardment Squadron

The 616th Bombardment Squadron was a U.S. Army Air Force bombardment squadron formed as part of the famed Tuskegee Airmen.-History:The squadron's members were involved in the civil rights action referred to as the Freeman Field Mutiny; the "mutiny" came about when African-American aviators became...

, 617th Bombardment Squadron

617th Bombardment Squadron

The 617th Bombardment Squadron was a U.S. Army Air Force bombardment squadron formed as part of the famed Tuskegee Airmen.-History:The squadron's members were involved in the civil rights action referred to as the Freeman Field Mutiny; the "mutiny" came about when African-American aviators became...

, 618th Bombardment Squadron

618th Bombardment Squadron

The 618th Bombardment Squadron was a U.S. Army Air Force bombardment squadron formed as part of the famed Tuskegee Airmen.-History:The squadron's members were involved in the civil rights action referred to as the Freeman Field Mutiny; the "mutiny" came about when African-American aviators became...

, and 619th Bombardment Squadron

619th Bombardment Squadron

The 619th Bombardment Squadron was a U.S. Army Air Force bombardment squadron formed as part of the famed Tuskegee Airmen.-History:The squadron's members were involved in the civil rights action referred to as the Freeman Field Mutiny; the "mutiny" came about when African-American aviators became...

. It was scheduled to enter combat on July 1, which made it necessary to relocate once more, this time to Freeman Army Airfield

Freeman Army Airfield

Freeman Army Airfield is an inactive United States Army Air Force base. It is located south-southwest of Seymour, Indiana.The base was established in 1942 as a pilot training airfield. It was also the first military helicopter pilot training airfield...

, a base fully suited to use by the B-25.

The protest at Freeman Field

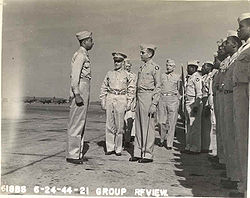

The incidents of April 5 and 6

The 477th began moving by train to Freeman Field on March 1, 1945. Word soon got back to the remaining African-American officers at Godman that Colonel Selway had created two separate officers' clubs at Freeman: Club Number One for use by "trainees," all of whom were black; and Club Number Two for use by "instructors," all of whom were white. Led by Second LieutenantSecond Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

Coleman A. Young

Coleman Young

Coleman Alexander Young served as mayor of Detroit in the U.S. state of Michigan from 1974 to 1993. Young became the first African-American mayor of Detroit in the same week that Maynard Jackson became the first African-American mayor of Atlanta.-Pre-Mayoral career:Young was born in Tuscaloosa,...

, the future mayor

Mayor

In many countries, a Mayor is the highest ranking officer in the municipal government of a town or a large urban city....

of Detroit and an experienced labor organizer, a group of black officers still at Godman decided on a plan of action to challenge the de facto segregation at Freeman as soon as they arrived there.

There had already been an attempt to integrate Club Number Two on March 10, when two groups of black officers entered it and were refused service; but the officers still at Godman decided to push the issue to the point of arrest if necessary. On April 5, the last of them left for Freeman. Arriving there late in the afternoon, they began to go in small groups to Club Number Two to seek service.

The first group of three officers was turned away by Major

Major

Major is a rank of commissioned officer, with corresponding ranks existing in almost every military in the world.When used unhyphenated, in conjunction with no other indicator of rank, the term refers to the rank just senior to that of an Army captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

Andrew M. White, the officer in charge of the club; but later groups were met by the Officer of the Day

Officer of the day

At smaller military installations where no provost marshal has been assigned, the officer of the day is a detail rotated each day among the unit/post's commissioned officers to oversee security, guard, and law enforcement considerations...

, First Lieutenant

First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a military rank and, in some forces, an appointment.The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations , but the majority of cases it is common for it to be sub-divided into a senior and junior rank...

Joseph D. Rogers, who was armed with a holstered .45 caliber weapon and who was stationed there on the orders of Colonel Selway. When 19 of the officers, including Coleman Young, entered the club against the instructions of Lieutenant Rogers and refused to leave, Major White put them in arrest "in quarters." In response to the arrest order, the 19 officers left the club and returned to their quarters. Seventeen more were placed under arrest later that night, including Second Lieutenant Roger C. Terry

Roger Terry

Lt. Roger "Bill" Terry was one of the Tuskegee Airmen. He served in the U.S. Army Air Corps in World War II. In 1945 he was stationed at Freeman Field, Indiana, where he was excluded from the "whites only" officers club, PX and theatre, which German POWs were allowed to attend...

, whom Lieutenant Rogers claimed had shoved him. The next night, 25 more officers acting in three groups entered the club and were also placed under arrest. Except for the alleged "shoving" incident, there was no use of physical force by anyone on either side. A total of 61 officers were arrested during the two-day protest.

Base Regulation 85-2

To make sure that none of the African-American officers could deny knowledge of the new regulation, Colonel Selway had his deputy commander, Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel is a rank of commissioned officer in the armies and most marine forces and some air forces of the world, typically ranking above a major and below a colonel. The rank of lieutenant colonel is often shortened to simply "colonel" in conversation and in unofficial correspondence...

John B. Pattison, assemble the trainees on April 10 and read them the regulation. After doing so, Colonel Pattison gave each officer a copy of the regulation and told them to sign a statement certifying that they had read it and fully understood it. No one signed. A subsequent effort by Captain Anthony A. Chiappe, commander of Squadron E, to coax 14 officers into signing produced only three signers. Finally, on the advice of Air Inspector Wold and a representative of the First Air Force Judge Advocate

Judge Advocate General's Corps

Judge Advocate General's Corps, also known as JAG or JAG Corps, refers to the legal branch or specialty of the U.S. Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, and Navy. Officers serving in the JAG Corps are typically called Judge Advocates. The Marine Corps and Coast Guard do not maintain separate JAG Corps...

, Colonel Selway set up a board consisting of two black officers and two white officers to interview the non-signers individually and present them with the following options:

- sign the certification;

- write and sign their own individual certificates in which they did not have to acknowledge that they understood the regulation; or

- face arrest under the 64th Article of War for disobeying a direct order by a superior officer in time of war, an offense that technically could be punished by death. See Uniform Code of Military JusticeUniform Code of Military JusticeThe Uniform Code of Military Justice , is the foundation of military law in the United States. It is was established by the United States Congress in accordance with the authority given by the United States Constitution in Article I, Section 8, which provides that "The Congress shall have Power . ....

, §890, Article 90, Assaulting or willfully disobeying superior commissioned officer.

The board carried out the interviews on April 11. One hundred one officers refused to sign and were placed under arrest in quarters.

Release of the 101

Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The Chief of Staff of the Army is a statutory office held by a four-star general in the United States Army, and is the most senior uniformed officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, and as such is the principal military advisor and a deputy to the Secretary of the Army; and is in...

General

General

A general officer is an officer of high military rank, usually in the army, and in some nations, the air force. The term is widely used by many nations of the world, and when a country uses a different term, there is an equivalent title given....

George C. Marshall, the 101 were released on April 23, although General Hunter placed an administrative reprimand in the file of each officer who had been arrested.

The three officers accused of "jostling" or "shoving" Lieutenant Rogers on the night of April 5 received a general court-martial in July. Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from October 1967 until October 1991...

, future associate justice of the United States Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

directed the defense, but did not himself appear for the defendants. Theodore M. Berry, future mayor of Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio. Cincinnati is the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located to north of the Ohio River at the Ohio-Kentucky border, near Indiana. The population within city limits is 296,943 according to the 2010 census, making it Ohio's...

, was lead defense counsel. He was assisted by Harold Tyler, a Chicago lawyer, and by Lieutenant William C. Coleman, who later became the chief defense counsel of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Second Lieutenants Marsden A. Thompson and Shirley R. Clinton were acquitted. Lieutenant Terry was acquitted of the charge of disobeying an order, but was convicted of the charge of jostling Lieutenant Rogers, for which he was fined $150, payable in three monthly installments, suffered loss of rank and received a dishonorable discharge.

Aftermath

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.

Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr. was an American born United States Air Force general and commander of the World War II Tuskegee Airmen....

, was appointed as commanding officer of the group on June 21, 1945, and took command on July 1. Black officers replaced white officers in subordinate command and supervisory positions. Training was to be completed by August 31, but the war ended on August 14 with Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

's surrender.

Never deployed in combat, the 477th Composite Group was downsized when the war ended. In 1946, it was reassigned to Lockbourne Field, now Rickenbacker International Airport

Rickenbacker International Airport

Rickenbacker International Airport is a joint civil-military public airport located 10 miles south of the central business district of Columbus, near the village of Lockbourne in extreme southern Franklin County, Ohio, United States. The southern end of the airport extends into northern Pickaway...

, in Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

. It was completely inactivated in 1947.

In 1948, President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

issued Executive Order 9981

Executive Order 9981

Executive Order 9981 is an executive order issued on July 26, 1948 by U.S. President Harry S. Truman. It expanded on Executive Order 8802 by establishing equality of treatment and opportunity in the Armed Services for people of all races, religions, or national origins."In 1947, Randolph, along...

, racially integrating

Racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration includes desegregation . In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity regardless of race, and the development of a culture that draws on diverse traditions, rather than merely...

the United States Armed Services.

When Freeman Field was inactivated in 1948, 2241 acres (9 km²) of the former base became Freeman Municipal Airport

Freeman Municipal Airport

Freeman Municipal Airport is a public use airport located two nautical miles southwest of the central business district of Seymour, a city in Jackson County, Indiana, United States. It is owned by the Seymour Airport Authority....

; 240 acre (0.9712464 km²) went for agricultural training in the Seymour Community Schools; and 60 acres (242,811.6 m²) became an industrial park.

In 1995, in response to requests from some of the veterans of the 477th, the Air Force officially removed General Hunter's letters of reprimand from the permanent files of 15 of the 104 officers charged in the Freeman Field protest and promised to remove the remaining 89 letters when requests were filed. Roger Terry received a full pardon, restoration of rank and a refund of his fine.

The events at Freeman Field, along with his own experiences in the USAAF, were the basis of the novel Guard of Honor

Guard of Honor

Guard of Honor is a Pulitzer Prize winning novel by James Gould Cozzens published in 1948. The novel is set during World War II, with most of the action occurring on or near a fictional Army Air Forces base in central Florida. The action occurs over a period of approximately 48 hours...

(ISBN 0-679-60305-0), for which James Gould Cozzens

James Gould Cozzens

James Gould Cozzens was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist.He is often grouped today with his contemporaries John O'Hara and John P. Marquand, but his work is generally considered more challenging. Despite initial critical acclaim, his popularity came gradually...

won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction has been awarded for distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. It originated as the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel, which was awarded between 1918 and 1947.-1910s:...

in 1949.

External links

- Afro-American Almanac:The Freeman Field Mutiny

- Official Site for Freeman Army Air Field (Freeman Field)

- IndianaMilitary.Org: Tuskegee Airmen at Freeman Army Air Field

- National Park Service:The Freeman Field Mutiny

- Atterbury-Bakalar Air Museum: The Tuskegee Airmen

- Silver Wings and Civil Rights: The Fight to Fly

- Page Two of the Story of the Tuskegee Airmen?

- Eyewitness to History: Roger "Bill" Terry Remembers

- Tavis Smiley Interviews Roger Terry

- The Freeman Field Mutiny by Tuskegee Airman O. Oliver Goodall

- Oral history interview with Tuskegee Airman, Connie Nappier, present at the Freeman Field Mutiny from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- Tracy Fisher, "Protests: Freeman Field," Graduate project prepared at George Mason University, Spring 2010.