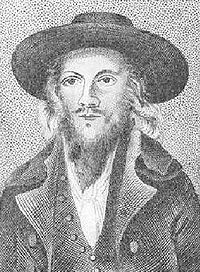

Lord George Gordon

Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

politician

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

best known for lending his name to the Gordon Riots

Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were an anti-Catholic protest against the Papists Act 1778.The Popery Act 1698 had imposed a number of penalties and disabilities on Roman Catholics in England; the 1778 act eliminated some of these. An initial peaceful protest led on to widespread rioting and looting and...

of 1780.

A colourful personality, he was born into the Scottish nobility and became a member of parliament for Ludgershall

Ludgershall (UK Parliament constituency)

Ludgershall was a parliamentary borough in Wiltshire, which elected two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons from 1295 until 1832, when the borough was abolished by the Great Reform Act.- 1295–1640 :- 1640–1832 :- Sources :...

. His life ended after a number of controversies, notably one surrounding his conversion to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism is a formal act undertaken by a non-Jewish person who wishes to be recognised as a full member of the Jewish community. A Jewish conversion is both a religious act and an expression of association with the Jewish people...

for which he was ostracised. He died in prison.

Early life

George Gordon was born in London, England, third and youngest son of Cosmo George Gordon, 3rd Duke of Gordon, and the brother of Alexander Gordon, 4th Duke of GordonAlexander Gordon, 4th Duke of Gordon

Alexander Gordon, 4th Duke of Gordon KT , styled Marquess of Huntly until 1752, was a Scottish nobleman, described by Kaimes as the "greatest subject in Britain", and was also known as the Cock o' the North, the traditional epithet attached to the chief of the Gordon clan.-Early life:Alexander...

. After completing his education at Eton

Eton College

Eton College, often referred to simply as Eton, is a British independent school for boys aged 13 to 18. It was founded in 1440 by King Henry VI as "The King's College of Our Lady of Eton besides Wyndsor"....

, he entered the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

in 1763 at the age of 12. He received promotion to the rank of Lieutenant, but his career stagnated and he received no further promotions. His behaviour in raising the poor living conditions of his sailors led to him being mistrusted by his fellow officers, although it contributed to his popularity amongst ordinary seamen.

Lord Sandwich

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, PC, FRS was a British statesman who succeeded his grandfather, Edward Montagu, 3rd Earl of Sandwich, as the Earl of Sandwich in 1729, at the age of ten...

, then at the head of the Admiralty, would not promise him the immediate command of a ship however, and he resigned his commission shortly before the beginning of the American War of Independence. In 1774 the pocket borough of Ludgershall

Ludgershall (UK Parliament constituency)

Ludgershall was a parliamentary borough in Wiltshire, which elected two Members of Parliament to the House of Commons from 1295 until 1832, when the borough was abolished by the Great Reform Act.- 1295–1640 :- 1640–1832 :- Sources :...

was bought for him by General Fraser, whom he was opposing in Inverness-shire

Inverness-shire (UK Parliament constituency)

Inverness-shire was a county constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of Great Britain from 1708 to 1801 and of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801 until 1918....

, in order to bribe him not to contest the county. He was considered flighty, and was not looked upon as being of any importance. From the moment he entered parliament he was a strong critic of the government's colonial policy in regard to America

British America

For American people of British descent, see British American.British America is the anachronistic term used to refer to the territories under the control of the Crown or Parliament in present day North America , Central America, the Caribbean, and Guyana...

. He became a supporter of American independence and often spoke out in favour of the colonies.

His chances of building a political following in parliament were damaged by his inconsistency and his tendency to criticise all the major political factions. He was just as likely to attack the radical opposition spokesman Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox PC , styled The Honourable from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned thirty-eight years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and who was particularly noted for being the arch-rival of William Pitt the Younger...

in a speech as he was to challenge Lord North, the Tory

Tory

Toryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

Prime Minister.

The "Gordon Riots"

Main articles: Gordon RiotsGordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were an anti-Catholic protest against the Papists Act 1778.The Popery Act 1698 had imposed a number of penalties and disabilities on Roman Catholics in England; the 1778 act eliminated some of these. An initial peaceful protest led on to widespread rioting and looting and...

and Trial of Lord George Gordon

Trial of Lord George Gordon

The Trial of Lord George Gordon for high treason occurred on 5 February 1781 before Lord Mansfield in the Court of King's Bench, as a result of his role in the Gordon Riots. Gordon, President of the Protestant Association, had led a protest against the Papists Act 1778, a Catholic relief bill...

.

In 1779 he organised, and made himself head of, the Protestant associations, formed to secure the repeal of the Catholic Relief Act of 1778.

On 2 June 1780 he headed a crowd of around 50,000 people that marched in procession from St George's Fields

St George's Fields

St George's Fields was an area of Southwark in South London, England.Originally the area was an undifferentiated part of the south-side of the Thames, which was low lying marshland unsuitable for even agricultural purposes. As such it was part of the extensive holdings of the king, it is difficult...

to the Houses of Parliament in order to present a huge petition

Petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer....

against (partial) Catholic Emancipation. After the mob reached Westminster the "Gordon Riots

Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were an anti-Catholic protest against the Papists Act 1778.The Popery Act 1698 had imposed a number of penalties and disabilities on Roman Catholics in England; the 1778 act eliminated some of these. An initial peaceful protest led on to widespread rioting and looting and...

" began. Initially, the mob dispersed after threatening to force their way into the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, but reassembled soon afterwards and, over several days, destroyed several Roman Catholic chapels, pillaged the private dwellings of Catholics, set fire to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison in London, at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey just inside the City of London. It was originally located at the site of a gate in the Roman London Wall. The gate/prison was rebuilt in the 12th century, and demolished in 1777...

, broke open all the other prisons, and attacked the Bank of England

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694, it is the second oldest central bank in the world...

and several other public buildings. The army was finally brought in to quell the unrest and killed or wounded around 450 people before they finally restored order.

For his role in instigating the riots, Lord George was charged with high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

. He was comfortably imprisoned in the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

and permitted to receive visitors, including the Methodist leader Rev. John Wesley

John Wesley

John Wesley was a Church of England cleric and Christian theologian. Wesley is largely credited, along with his brother Charles Wesley, as founding the Methodist movement which began when he took to open-air preaching in a similar manner to George Whitefield...

on Tuesday 19 December 1780.

Thanks to a strong defence by his cousin, Thomas, Lord Erskine

Thomas Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine

Thomas Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine KT PC KC was a British lawyer and politician. He served as Lord Chancellor of the United Kingdom between 1806 and 1807 in the Ministry of All the Talents.-Background and childhood:...

, he was acquitted on the grounds that he had no treasonable intent.

Imprisonment

In 1786 he was excommunicated by the archbishop of CanterburyArchbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

for refusing to bear witness in an ecclesiastical suit; and in 1787 he was convicted of defaming Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette ; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I....

, the French ambassador and the administration of justice in England. He was, however, permitted to withdraw from the court without bail, and made his escape to the Netherlands. On account of representations from the court of Versailles

Versailles

Versailles , a city renowned for its château, the Palace of Versailles, was the de facto capital of the kingdom of France for over a century, from 1682 to 1789. It is now a wealthy suburb of Paris and remains an important administrative and judicial centre...

he was commanded to leave that country, and, returning to England, was apprehended, and in January 1788 was sentenced to five years' imprisonment in Newgate and some harsh additional conditions.

Conversion to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism is a formal act undertaken by a non-Jewish person who wishes to be recognised as a full member of the Jewish community. A Jewish conversion is both a religious act and an expression of association with the Jewish people...

to Judaism in Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

, circumcised at the synagogue in Severn Street now next door to Singers Hill Synagogue, something rare in the England of his day. He took the name of Yisrael bar Avraham Gordon ("Israel son of Abraham

Abraham

Abraham , whose birth name was Abram, is the eponym of the Abrahamic religions, among which are Judaism, Christianity and Islam...

" Gordon—since Judaism regards a convert as the spiritual "son" of the Biblical Abraham) and underwent brit milah

Brit milah

The brit milah is a Jewish religious circumcision ceremony performed on 8-day old male infants by a mohel. The brit milah is followed by a celebratory meal .-Biblical references:...

("circumcision"). Gordon thus became what Judaism regards as, and Jews call, a "Ger Tsedek"—a righteous convert.

Not much is known about his life as a Jew in Birmingham, but the Bristol Journal of 15 Dec. 1787 reported that Gordon had been living in Birmingham since August, 1786 (its incorrect perceptions and interpretations of Judaism notwithstanding):

He lived with a Jewish woman in the froggery area (marshy area) of Birmingham which is now New street station.

...

While in jail, Gordon lived the life of an Orthodox

Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism , is the approach to Judaism which adheres to the traditional interpretation and application of the laws and ethics of the Torah as legislated in the Talmudic texts by the Sanhedrin and subsequently developed and applied by the later authorities known as the Gaonim, Rishonim, and...

Jew, and he adjusted his prison life to his circumstances. He put on his tzitzit

Tzitzit

The Hebrew noun tzitzit is the name for specially knotted ritual fringes worn by observant Jews. Tzitzit are attached to the four corners of the tallit and tallit katan.-Etymology:The word may derive from the semitic root N-TZ-H...

and tefillin

Tefillin

Tefillin also called phylacteries are a set of small black leather boxes containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah, which are worn by observant Jews during weekday morning prayers. Although "tefillin" is technically the plural form , it is loosely used as a singular as...

daily. He fasted when the halakha

Halakha

Halakha — also transliterated Halocho , or Halacha — is the collective body of Jewish law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions.Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life; Jewish...

(Jewish law) prescribed it, and likewise celebrated the Jewish holiday

Jewish holiday

Jewish holidays are days observed by Jews as holy or secular commemorations of important events in Jewish history. In Hebrew, Jewish holidays and festivals, depending on their nature, may be called yom tov or chag or ta'anit...

s. He had kosher meat and wine, and Shabbat

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

challos

Challah

Challah also khale ,, berches , barkis , bergis , chałka , vánočka , zopf and kitke , is a special braided bread eaten on...

. The prison authorities permitted him to have a minyan

Minyan

A minyan in Judaism refers to the quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain religious obligations. According to many non-Orthodox streams of Judaism adult females count in the minyan....

on Shabbat and to affix a mezuza to his room. The Ten Commandments

Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments, also known as the Decalogue , are a set of biblical principles relating to ethics and worship, which play a fundamental role in Judaism and most forms of Christianity. They include instructions to worship only God and to keep the Sabbath, and prohibitions against idolatry,...

were also hung on his wall for Shabbat to transform the room into a synagogue

Synagogue

A synagogue is a Jewish house of prayer. This use of the Greek term synagogue originates in the Septuagint where it sometimes translates the Hebrew word for assembly, kahal...

.

Lord George Gordon associated only with pious

Frum

The Yiddish adjective frum , from the German fromm, meaning "devout" or "pious", is a Yiddish word meaning committed to be observant of the 613 commandments, or Jewish commandments, specifically of Orthodox Judaism...

Jews; in his passionate enthusiasm for his new faith, he refused to deal with any Jew who compromised the Torah

Torah

Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five books of the bible—Genesis , Exodus , Leviticus , Numbers and Deuteronomy Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five...

's commandments. Although any non-Jew who desired to visit Gordon in prison (and there were many) was welcome, he requested that the prison guards admit Jews only if they had beards and wore head coverings.

He would often, in keeping with Jewish chesed (Mercy and Charity

Charity (virtue)

In Christian theology charity, or love , means an unlimited loving-kindness toward all others.The term should not be confused with the more restricted modern use of the word charity to mean benevolent giving.- Caritas: altruistic love :...

) Law, go into other parts of the prison to comfort prisoners by speaking with them and playing the violin. In keeping with tzedaka (Charity) laws, he gave what little money he could to those in need.

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

, in his novel Barnaby Rudge

Barnaby Rudge

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty is a historical novel by British novelist Charles Dickens. Barnaby Rudge was one of two novels that Dickens published in his short-lived weekly serial Master Humphrey's Clock...

, which centres around the "Gordon" riots of 1780, describes Gordon as a true Tzadik

Tzadik

Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq is a title given to personalities in Jewish tradition considered righteous, such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d-q , which means "justice" or "righteousness", also the root of Tzedakah...

(Pious Man) among the prisoners as follows:

Death

On 28 January 1793, Lord George Gordon's sentence expired and he had to appear to give claim to his future good behaviour. When appearing in court he was ordered to remove his hat, which he refused to do. The hat was then taken from him by force, but he covered his head with a night cap and bound it with a handkerchief. He defended his behaviour concerning his kippahKippah

A kippah or kipa , also known as a yarmulke , kapele , is a hemispherical or platter-shaped head cover, usually made of cloth, often worn by Orthodox Jewish men to fulfill the customary requirement that their head be covered at all times, and sometimes worn by both men and, less frequently, women...

by quoting the Hebrew Bible

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible is a term used by biblical scholars outside of Judaism to refer to the Tanakh , a canonical collection of Jewish texts, and the common textual antecedent of the several canonical editions of the Christian Old Testament...

"in support of the propriety of the creature having his head covered in reverence to the Creator." Before the court, he read a written statement in which he claimed that "he had been imprisoned for five years among murderers, thieves, etc., and that all the consolation he had arose from his trust in God."

Since he had brought as guarantors two Jews, whom the court would not accept as witnesses, Gordon was again remanded to his prison cell. Although his brothers, the 4th Duke of Gordon

Alexander Gordon, 4th Duke of Gordon

Alexander Gordon, 4th Duke of Gordon KT , styled Marquess of Huntly until 1752, was a Scottish nobleman, described by Kaimes as the "greatest subject in Britain", and was also known as the Cock o' the North, the traditional epithet attached to the chief of the Gordon clan.-Early life:Alexander...

and Lord William (the future Vice-Admiral), and his sister, Lady Westmorland, offered to cover his bail, Gordon refused their help, saying that to "sue for pardon was a confession of guilt."

In October of the same year, Gordon caught the typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

that had been raging in Newgate throughout 1793. Christopher Hibbert

Christopher Hibbert

Christopher Hibbert, MC, FRSL, FRGS was an English writer, historian and biographer. He has been called "a pearl of biographers" and "probably the most widely-read popular historian of our time and undoubtedly one of the most prolific"...

, another biographer, writes that scores of prisoners waited outside his door for news about his health; friends, regardless of the risk of infection, stood whispering in the room and praying for his recovery - but George Yisrael bar Avraham Gordon died on 1 November 1793, 26 Mar-Cheshvan 5554, at the age of 42.

Gordon's life story can be found in Lord George Gordon, by Yirmeyahu Bindman, 1992, ISBN 1-56062-056-0, LOC 90-86061, which has a 15 item Bibliography

Bibliography

Bibliography , as a practice, is the academic study of books as physical, cultural objects; in this sense, it is also known as bibliology...

and a brief Glossary

Glossary

A glossary, also known as an idioticon, vocabulary, or clavis, is an alphabetical list of terms in a particular domain of knowledge with the definitions for those terms...

of Jewish religious terms used in the 203+ page book.

A serious defence is undertaken in The Life of Lord George Gordon, with a Philosophical Review of his Political Conduct, by Robert Watson

Robert Watson

Robert Watson may refer to:* Robert Watson * Robert Watson * Robert Watson , computer scientist* Robert Watson , Canadian parliamentarian...

, M.D. (London, 1795). The best accounts of Lord George Gordon are to be found in the Annual Registers from 1780 to the year of his death.