Post-Turing machine

Encyclopedia

A Post–Turing machine is a "program formulation" of an especially simple type of Turing machine

, comprising a variant of Emil Post's Turing-equivalent

model of computation

described below. (Post's model and Turing's model, though very similar to one another, were developed independently. Turing's paper was received for publication in May of 1936, followed by Post's in October.) A Post–Turing machine uses a binary alphabet

, an infinite sequence

of binary storage

locations, and a primitive programming language

with instructions for bi-directional movement among the storage locations and alteration of their contents one at a time. The names "Post–Turing program" and "Post–Turing machine" were used by Martin Davis

in 1973–1974 (Davis 1973, p.69ff). Later in 1980, Davis used the name "Turing–Post program" (Davis, in Steen p. 241).

", and which was later proved to be so. The quotes in the following are from this paper.

Post's model of a computation differs from the Turing-machine model in a further "atomization" of the acts a human "computer" would perform during a computation.

Post's model employs a "symbol

space" consisting of a "two-way infinite sequence of spaces or boxes", each box capable of being in either of two possible conditions, namely "marked" (as by a single vertical stroke) and "unmarked" (empty). Initially, finitely-many of the boxes are marked, the rest being unmarked. A "worker" is then to move among the boxes, being in and operating in only one box at a time, according to a fixed finite "set of directions" (instructions), which are numbered in order (1,2,3,...,n). Beginning at a box "singled out as the starting point", the worker is to follow the set of instructions one at a time, beginning with instruction 1.

The instructions may require the worker to perform the following "basic acts" or "operations

":

Marking the box he is in (assumed empty), Erasing the mark in the box he is in (assumed marked), Moving to the box on his right, Moving to the box on his left, Determining whether the box he is in, is or is not marked.

Specifically, the i th "direction" (instruction) given to the worker is to be one of the following forms:

(The above indented text and italics are as in the original.) Post remarks that this formulation is "in its initial stages" of development, and mentions several possibilities for "greater flexibility" in its final "definitive form", including

, Post, in his paper of 1947 (Recursive Unsolvability of a Problem of Thue) atomized the Turing 5-tuples to 4-tuples:

Like Turing he defined erasure as printing a symbol "S0". And so his model admitted quadruplets of only three types (cf p. 294 Undecidable):

At this time he was still retaining the Turing state-machine convention – he had not formalized the notion of an assumed sequential execution of steps until a specific test of a symbol "branched" the execution elsewhere.

.

Wang (1957, but presented to the ACM in 1954) is often cited (cf Minsky (1967) p. 200) as the source of the "program formulation" of binary-tape Turing machines using numbered instructions from the set

where sequential execution

is assumed, and Post's single "if ... then ... else

" has been "atomised" into two "if ... then ..." statements. (Here '1' and '0' are used where Wang used "marked" and "unmarked", respectively, and the initial tape is assumed to contain only '0's except for finitely-many '1's.)

Wang noted the following:

Any binary-tape Turing machine is readily converted to an equivalent "Wang program" using the above instructions.

(Davis (2000) 1st and 2nd footnotes p. 188).

The following model he presented in a series of lectures to the Courant Institute at NYU in 1973–1974. This is the model to which Davis formally applied the name "Post–Turing machine" with its "Post–Turing language". The instructions are assumed to be executed sequentially (Davis 1974, p. 71):

Note that there is no "halt" or "stop".

In the following model Davis assigns the numbers "1" to Post's "mark/slash" and "0" to the blank square. To quote Davis: "We are now ready to introduce the Turing–Post Programming Language. In this language there are seven kinds of instructions:

"A Turing–Post program is then a list of instructions, each of which is of one of these seven kinds. Of course in an actual program the letter i in a step of either the fifth or sixth kind must replaced with a definite (positive whole) number." (Davis in Steen, p. 247).

This model allows for the printing of multiple symbols. The model allows for B (blank) instead of S0. The tape is infinite in both directions. Either the head or the tape moves, but their definitions of RIGHT and LEFT always specify the same outcome in either case (Turing used the same convention).

Note that only one type of "jump" – a conditional GOTO – is specified; for an unconditional jump a string of GOTO's must test each symbol.

This model reduces to the binary { 0, 1 } versions presented above, as shown here:

(italics in original, cf Minsky (1961) p. 439).

(Minsky's reduction to what he calls "a sub-routine" results in 5 rather than 7 Post–Turing instructions. He did not atomize Wi0: "Write symbol Si0; go to new state Mi0", and Wi1: "Write symbol Si1; go to new state Mi1". The following method further atomizes Wi0 and Wi1; in all other respects the methods are identical.)

This reduction of Turing 5-tuples to Post–Turing instructions may not result in an "efficient" Post–Turing program, but it will be faithful to the original Turing-program.

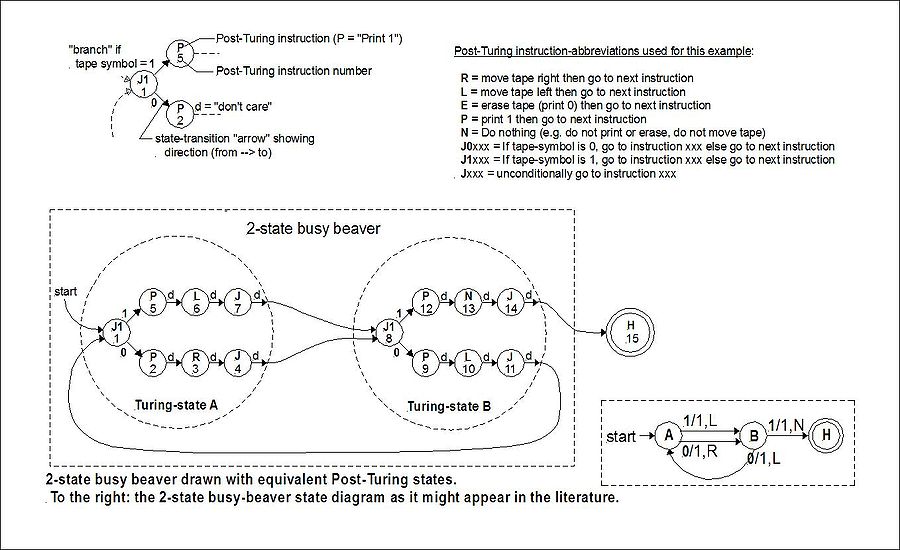

In the following example, each Turing 5-tuple of the 2-state busy beaver

converts into an initial conditional "jump" (goto, branch), followed by 2 tape-action instructions for the "0" case – Print or Erase or None, followed by Left or Right or None, followed by an unconditional "jump" for the "0" case to its next instruction 2 tape-action instructions for the "1" case – Print or Erase or None, followed by Left or Right or None, followed by an unconditional "jump" for the "1" case to its next instruction

for a total of 1 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 1 = 7 instructions per Turing-state.

For example, the 2-state busy beaver's "A" Turing-state, written as two lines of 5-tuples, is:

The table represents just a single Turing "instruction", but we see that it consists of two lines of 5-tuples, one for the case "tape symbol under head = 1", the other for the case "tape symbol under head = 0". Turing observed (Undecidable, p. 119) that the left-two columns – "m-configuration" and "symbol" – represent the machine's current "configuration" – its state including both Tape and Table at that instant – and the last three columns are its subsequent "behavior". As the machine cannot be in two "states" at once, the machine must "branch" to either one configuration or the other:

After the "configuration branch" (J1 xxx) or (J0 xxx) the machine follows one of the two subsequent "behaviors". We list these two behaviors on one line, and number (or label) them sequentially (uniquely). Beneath each jump (branch, go to) we place its jump-to "number" (address, location):

Per the Post–Turing machine conventions each of the Print, Erase, Left, and Right instructions consist of two actions:

And per the Post–Turing machine conventions the conditional "jumps" J0xxx, J1xxx consist of two actions:

And per the Post–Turing machine conventions the unconditional "jump" Jxxx consists of a single action, or if we want to regularize the 2-action sequence:

Which, and how many, jumps are necessary? The unconditional jump Jxxx is simply J0 followed immediately by J1 (or vice versa). Wang (1957) also demonstrates that only one conditional jump is required, i.e. either J0xxx or J1xxx. However, with this restriction the machine becomes difficult to write instructions for. Often only two are used, i.e. { J0xxx, J1xxx } { J1xxx, Jxxx } { J0xxx, Jxxx },

but the use of all three { J0xxx, J1xxx, Jxxx } does eliminate extra instructions. In the 2-state Busy Beaver example that we use only { J1xxx, Jxxx }.

is to print as many ones as possible before halting. The "Print" instruction writes a 1, the "Erase" instruction (not used in this example) writes a 0 (i.e. it is the same as P0). The tape moves "Left" or "Right" (i.e. the "head" is stationary).

State table for a 2-state Turing-machine busy beaver

:

Instructions for the Post–Turing version of a 2-state busy beaver: observe that all the instructions are on the same line and in sequence. This is a significant departure from the "Turing" version and is in the same format as what is called a "computer program":

Alternately, we might write the table as a string. The use of "parameter separators" ":" and instruction-separators "," are entirely our choice and do not appear in the model. There are no conventions (but see Booth (1967) p. 374, and Boolos and Jeffrey (1974, 1999) p. 23), for some useful ideas of how to combine state diagram conventions with the instructions – i.e. to use arrows to indicate the destination of the jumps). In the example immediately below, the instructions are sequential starting from "1", and the parameters/"operands" are considered part of their instructions/"opcodes":

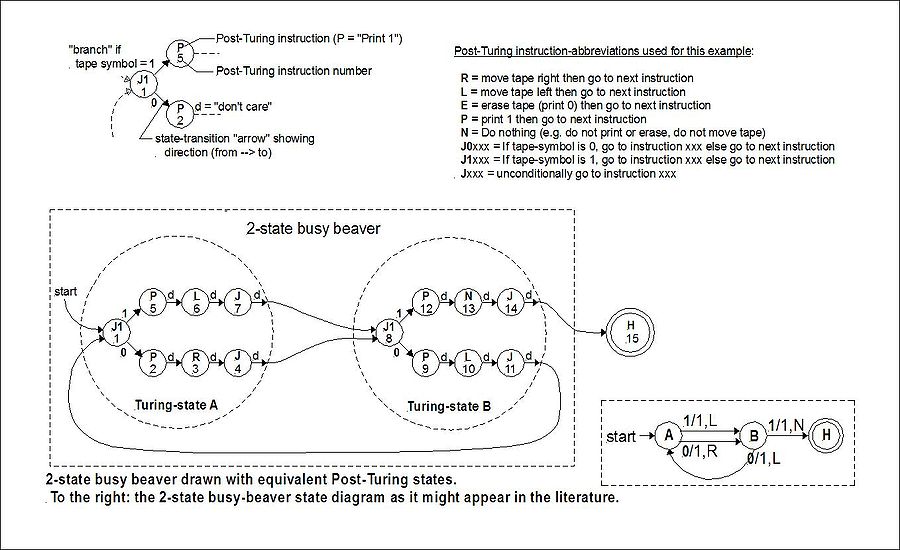

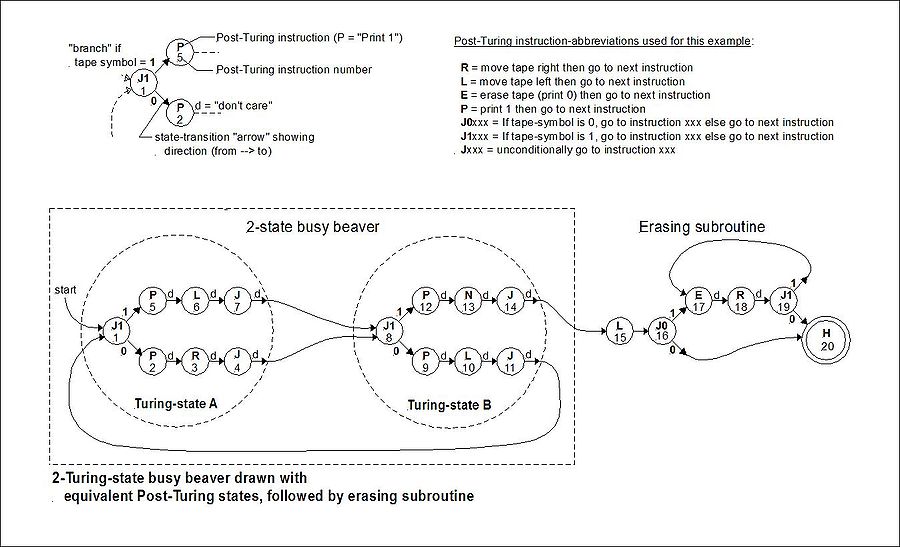

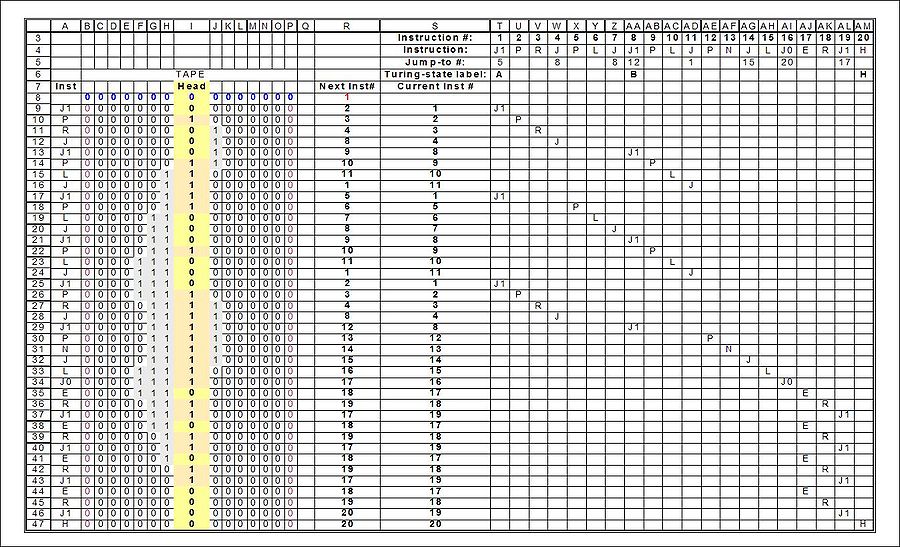

The state diagram of a two-state busy beaver (little drawing, right-hand corner) converts to the equivalent Post–Turing machine with the substitution of 7 Post–Turing instructions per "Turing" state. The HALT instruction adds the 15th state:

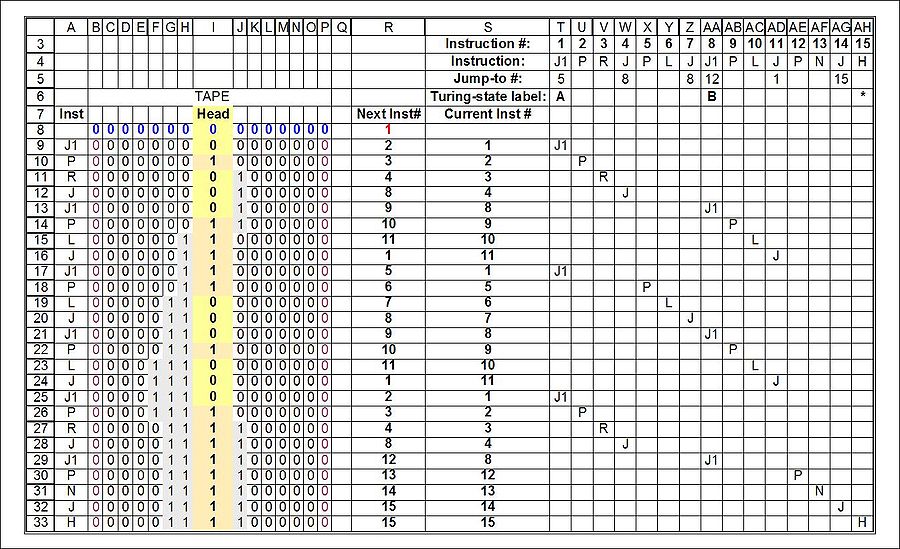

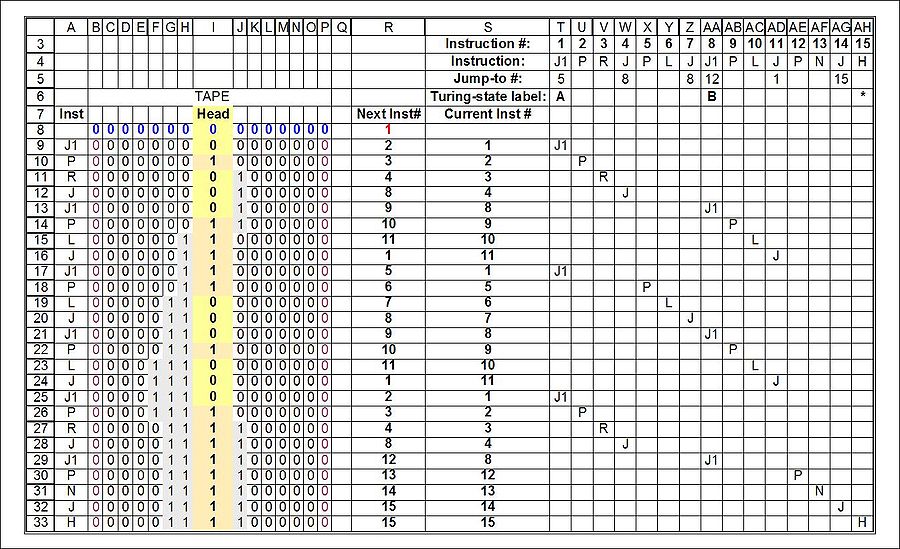

A "run" of the 2-state busy beaver with all the intermediate steps of the Post–Turing machine shown:

A "run" of the 2-state busy beaver with all the intermediate steps of the Post–Turing machine shown:

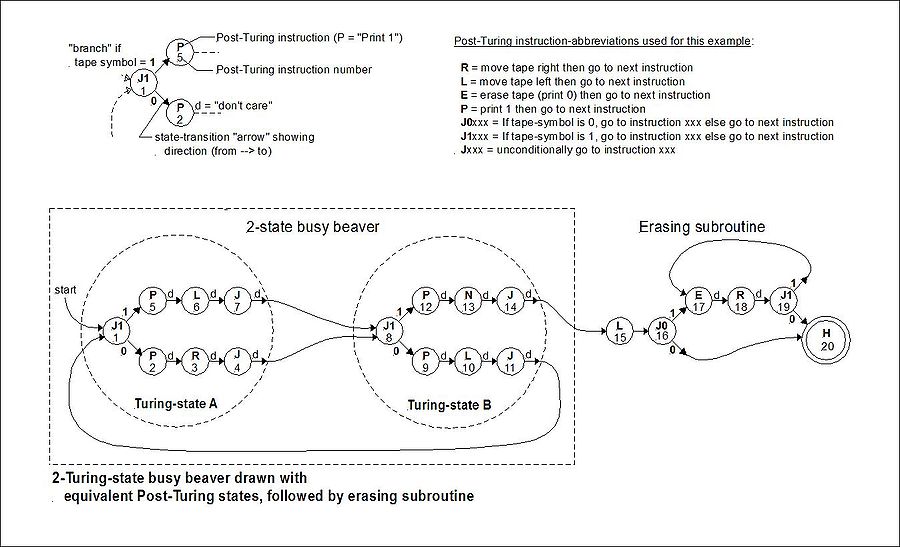

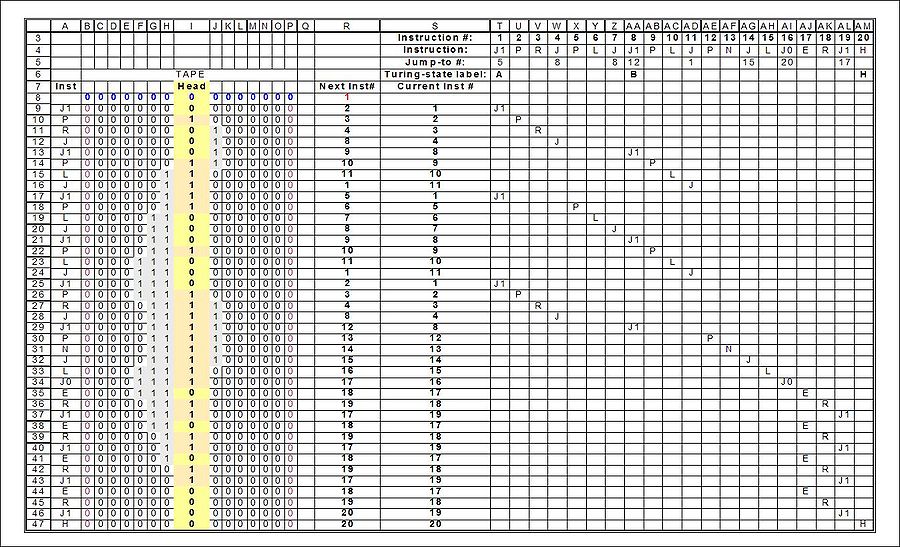

Additional Post–Turing instructions 15 through 20 erase the symbols created by the busy beaver. These "atomic" instructions are more "efficient" than their Turing-state equivalents (of 7 Post–Turing instructions). To accomplish the same task a Post–Turing machine will (usually) require fewer Post–Turing states than a Turing-machine, because (i) a jump (go-to) can occur to any Post–Turing instruction (e.g. P, E, L, R) within the Turing-state, (ii) a grouping of move-instructions such as L, L, L, P are possible, etc.:

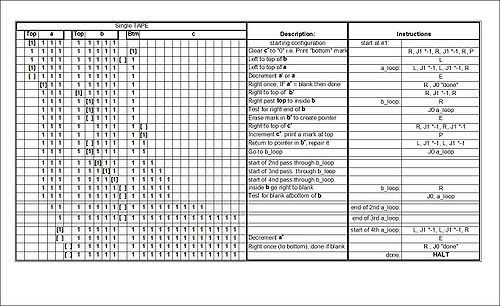

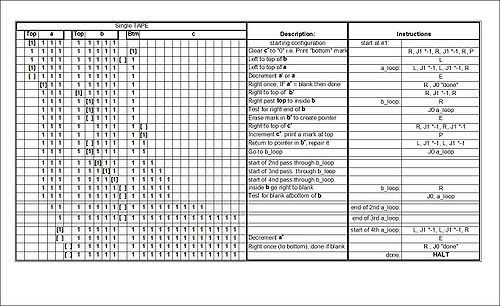

This example is a reference to show how a "multiply" computation would proceed on a single-tape, 2-symbol { blank, 1 } Post–Turing machine model.

This example is a reference to show how a "multiply" computation would proceed on a single-tape, 2-symbol { blank, 1 } Post–Turing machine model.

This particular "multiply" algorithm is recursive through two loops. The head moves. It starts to the far left (the top) of the string of unary marks representing a' :

Turing machine

A Turing machine is a theoretical device that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite its simplicity, a Turing machine can be adapted to simulate the logic of any computer algorithm, and is particularly useful in explaining the functions of a CPU inside a...

, comprising a variant of Emil Post's Turing-equivalent

Turing completeness

In computability theory, a system of data-manipulation rules is said to be Turing complete or computationally universal if and only if it can be used to simulate any single-taped Turing machine and thus in principle any computer. A classic example is the lambda calculus...

model of computation

Computation

Computation is defined as any type of calculation. Also defined as use of computer technology in Information processing.Computation is a process following a well-defined model understood and expressed in an algorithm, protocol, network topology, etc...

described below. (Post's model and Turing's model, though very similar to one another, were developed independently. Turing's paper was received for publication in May of 1936, followed by Post's in October.) A Post–Turing machine uses a binary alphabet

Binary numeral system

The binary numeral system, or base-2 number system, represents numeric values using two symbols, 0 and 1. More specifically, the usual base-2 system is a positional notation with a radix of 2...

, an infinite sequence

Sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an ordered list of objects . Like a set, it contains members , and the number of terms is called the length of the sequence. Unlike a set, order matters, and exactly the same elements can appear multiple times at different positions in the sequence...

of binary storage

Computer storage

Computer data storage, often called storage or memory, refers to computer components and recording media that retain digital data. Data storage is one of the core functions and fundamental components of computers....

locations, and a primitive programming language

Programming language

A programming language is an artificial language designed to communicate instructions to a machine, particularly a computer. Programming languages can be used to create programs that control the behavior of a machine and/or to express algorithms precisely....

with instructions for bi-directional movement among the storage locations and alteration of their contents one at a time. The names "Post–Turing program" and "Post–Turing machine" were used by Martin Davis

Martin Davis

Martin David Davis, is an American mathematician, known for his work on Hilbert's tenth problem . He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University in 1950, where his adviser was Alonzo Church . He is Professor Emeritus at New York University. He is the co-inventor of the Davis-Putnam and the DPLL...

in 1973–1974 (Davis 1973, p.69ff). Later in 1980, Davis used the name "Turing–Post program" (Davis, in Steen p. 241).

1936: Post model

In his 1936 paper "Finite combinatory processes—formulation 1" (which can be found on page 289 of The Undecidable), Emil Post described a model of extreme simplicity which he conjectured is "logically equivalent to recursivenessRecursive function

Recursive function may refer to:*Recursion , a procedure or subroutine, implemented in a programming language, whose implementation references itself*A total computable function, a function which is defined for all possible inputs...

", and which was later proved to be so. The quotes in the following are from this paper.

Post's model of a computation differs from the Turing-machine model in a further "atomization" of the acts a human "computer" would perform during a computation.

Post's model employs a "symbol

Mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is a subfield of mathematics with close connections to foundations of mathematics, theoretical computer science and philosophical logic. The field includes both the mathematical study of logic and the applications of formal logic to other areas of mathematics...

space" consisting of a "two-way infinite sequence of spaces or boxes", each box capable of being in either of two possible conditions, namely "marked" (as by a single vertical stroke) and "unmarked" (empty). Initially, finitely-many of the boxes are marked, the rest being unmarked. A "worker" is then to move among the boxes, being in and operating in only one box at a time, according to a fixed finite "set of directions" (instructions), which are numbered in order (1,2,3,...,n). Beginning at a box "singled out as the starting point", the worker is to follow the set of instructions one at a time, beginning with instruction 1.

The instructions may require the worker to perform the following "basic acts" or "operations

Operation (mathematics)

The general operation as explained on this page should not be confused with the more specific operators on vector spaces. For a notion in elementary mathematics, see arithmetic operation....

":

Marking the box he is in (assumed empty), Erasing the mark in the box he is in (assumed marked), Moving to the box on his right, Moving to the box on his left, Determining whether the box he is in, is or is not marked.

Specifically, the i th "direction" (instruction) given to the worker is to be one of the following forms:

- (A) Perform operation Oi [Oi = (a), (b), (c) or (d)] and then follow direction ji,

- (B) Perform operation (e) and according as the answer is yes or no correspondingly follow direction ji' or ji' ' ,

- (C) Stop.

(The above indented text and italics are as in the original.) Post remarks that this formulation is "in its initial stages" of development, and mentions several possibilities for "greater flexibility" in its final "definitive form", including

- (1) replacing the infinity of boxes by a finite extensible symbol space, "extending the primitive operations to allow for the necessary extension of the given finite symbol space as the process proceeds",

- (2) using an alphabet of more than two symbols, "having more than one way to mark a box",

- (3) introducing finitely-many "physical objects to serve as pointers, which the worker can identify and move from box to box".

1947: Post's formal reduction of the Turing 5-tuples to 4-tuples

As briefly mentioned in the article Turing machineTuring machine

A Turing machine is a theoretical device that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite its simplicity, a Turing machine can be adapted to simulate the logic of any computer algorithm, and is particularly useful in explaining the functions of a CPU inside a...

, Post, in his paper of 1947 (Recursive Unsolvability of a Problem of Thue) atomized the Turing 5-tuples to 4-tuples:

- "Our quadruplets are quintuplets in the Turing development. That is, where our standard instruction orders either a printing (overprinting) or motion, left or right, Turing's standard instruction always order a printing and a motion, right, left, or none"(footnote 12, Undecidable p. 300)

Like Turing he defined erasure as printing a symbol "S0". And so his model admitted quadruplets of only three types (cf p. 294 Undecidable):

- qi Sj L ql,

- qi Sj R ql,

- qi Sj Sk ql

At this time he was still retaining the Turing state-machine convention – he had not formalized the notion of an assumed sequential execution of steps until a specific test of a symbol "branched" the execution elsewhere.

1954, 1957: Wang model

For an even further reduction – to only four instructions – of the Wang model presented here see Wang B-machineWang B-machine

As presented by Hao Wang , his basic machine B is an extremely simple computational model equivalent to the Turing machine. It is "the first formulation of a Turing-machine theory in terms of computer-like models" . With only 4 sequential instructions it is very similar to, but even simpler than,...

.

Wang (1957, but presented to the ACM in 1954) is often cited (cf Minsky (1967) p. 200) as the source of the "program formulation" of binary-tape Turing machines using numbered instructions from the set

- write 0

- write 1

- move left

- move right

- if scanning 0 then goto instruction i

- if scanning 1 then goto instruction j

where sequential execution

Execution (computers)

Execution in computer and software engineering is the process by which a computer or a virtual machine carries out the instructions of a computer program. The instructions in the program trigger sequences of simple actions on the executing machine...

is assumed, and Post's single "if ... then ... else

Conditional statement

In computer science, conditional statements, conditional expressions and conditional constructs are features of a programming language which perform different computations or actions depending on whether a programmer-specified boolean condition evaluates to true or false...

" has been "atomised" into two "if ... then ..." statements. (Here '1' and '0' are used where Wang used "marked" and "unmarked", respectively, and the initial tape is assumed to contain only '0's except for finitely-many '1's.)

Wang noted the following:

- "Since there is no separate instruction for halt (stop), it is understood that the machine will stop when it has arrived at a stage that the program contains no instruction telling the machine what to do next." (p.65)

- "In contrast with Turing who uses a one-way infinite tape that has a beginning, we are following Post in the use of a 2-way infinite tape." (p. 65)

- Unconditional gotos are easily derived from the above instructions, so "we can freely use them too". (p.84)

Any binary-tape Turing machine is readily converted to an equivalent "Wang program" using the above instructions.

1974: first Davis model

Martin Davis was a undergraduate student of Emil Post's. Along with Stephen Kleene he completed his PhD under Alonzo ChurchAlonzo Church

Alonzo Church was an American mathematician and logician who made major contributions to mathematical logic and the foundations of theoretical computer science. He is best known for the lambda calculus, Church–Turing thesis, Frege–Church ontology, and the Church–Rosser theorem.-Life:Alonzo Church...

(Davis (2000) 1st and 2nd footnotes p. 188).

The following model he presented in a series of lectures to the Courant Institute at NYU in 1973–1974. This is the model to which Davis formally applied the name "Post–Turing machine" with its "Post–Turing language". The instructions are assumed to be executed sequentially (Davis 1974, p. 71):

- "Write 1

- "Write B

- "To A if read 1

- "To A if read B

- "RIGHT

- "LEFT

Note that there is no "halt" or "stop".

1978 second Davis model

The following model appears as an essay What is a computation? in Steen pages 241–267. For some reason Davis has renamed his model a "Turing–Post machine" (with one back-sliding on page 256.)In the following model Davis assigns the numbers "1" to Post's "mark/slash" and "0" to the blank square. To quote Davis: "We are now ready to introduce the Turing–Post Programming Language. In this language there are seven kinds of instructions:

-

- "PRINT 1

- "PRINT 0

- "GO RIGHT

- "GO LEFT

- "GO TO STEP i IF 1 IS SCANNED

- "GO TO STEP i IF 0 IS SCANNED

- "STOP

"A Turing–Post program is then a list of instructions, each of which is of one of these seven kinds. Of course in an actual program the letter i in a step of either the fifth or sixth kind must replaced with a definite (positive whole) number." (Davis in Steen, p. 247).

- Confusion arises if one does not realize that a "blank" tape is actually printed with all zeroes — there is no "blank".

- Splits Post's "GO TOGotogoto is a statement found in many computer programming languages. It is a combination of the English words go and to. It performs a one-way transfer of control to another line of code; in contrast a function call normally returns control...

" ("branchBranch (computer science)A branch is sequence of code in a computer program which is conditionally executed depending on whether the flow of control is altered or not . The term can be used when referring to programs in high level languages as well as program written in machine code or assembly language...

" or "jump") instruction into two, thus creating a larger (but easier-to-use) instruction set of seven rather than Post's six instructions. - Does not mention that instructions PRINTInput/outputIn computing, input/output, or I/O, refers to the communication between an information processing system , and the outside world, possibly a human, or another information processing system. Inputs are the signals or data received by the system, and outputs are the signals or data sent from it...

1, PRINT 0, GO RIGHT and GO LEFT imply that, after execution, the "computer" must go to the next step in numerical sequence.

1994 (2nd Edition) Davis–Sigal–Weyuker's Post–Turing program model

"Although the formulation of Turing we have presented is closer in spirit to that originally given by Emil Post, it was Turing's analysis of the computation that has made this formulation seem so appropriate. This language has played a fundamental role in theoretical computer science." (Davis et al. (1994) p. 129)This model allows for the printing of multiple symbols. The model allows for B (blank) instead of S0. The tape is infinite in both directions. Either the head or the tape moves, but their definitions of RIGHT and LEFT always specify the same outcome in either case (Turing used the same convention).

-

- PRINT σ ;Replace scanned symbol with σ

- IF σ GOTO L ;IF scanned symbol is σ THEN goto "the first" instruction labelled L

- RIGHT ;Scan square immediately right of the square currently scanned

- LEFT ;Scan square immediately left of the square currently scanned

Note that only one type of "jump" – a conditional GOTO – is specified; for an unconditional jump a string of GOTO's must test each symbol.

This model reduces to the binary { 0, 1 } versions presented above, as shown here:

-

- PRINT 0 = ERASE ;Replace scanned symbol with 0 = B = BLANK

- PRINT 1 ;Replace scanned symbol with 1

- IF 0 GOTO L ;IF scanned symbol is 0 THEN goto "the first" instruction labelled L

- IF 1 GOTO L ;IF scanned symbol is 1 THEN goto "the first" instruction labelled L

- RIGHT ;Scan square immediately right of the square currently scanned

- LEFT ;Scan square immediately left of the square currently scanned

Atomizing Turing quintuples into a sequence of Post–Turing instructions

The following "reduction" (decomposition, atomizing) method – from 2-symbol Turing 5-tuples to a sequence of 2-symbol Post–Turing instructions – can be found in Minsky (1961). He states that this reduction to "a program ... a sequence of Instructions" is in the spirit of Hao Wang's B-machineWang B-machine

As presented by Hao Wang , his basic machine B is an extremely simple computational model equivalent to the Turing machine. It is "the first formulation of a Turing-machine theory in terms of computer-like models" . With only 4 sequential instructions it is very similar to, but even simpler than,...

(italics in original, cf Minsky (1961) p. 439).

(Minsky's reduction to what he calls "a sub-routine" results in 5 rather than 7 Post–Turing instructions. He did not atomize Wi0: "Write symbol Si0; go to new state Mi0", and Wi1: "Write symbol Si1; go to new state Mi1". The following method further atomizes Wi0 and Wi1; in all other respects the methods are identical.)

This reduction of Turing 5-tuples to Post–Turing instructions may not result in an "efficient" Post–Turing program, but it will be faithful to the original Turing-program.

In the following example, each Turing 5-tuple of the 2-state busy beaver

Busy beaver

In computability theory, a busy beaver is a Turing machine that attains the maximum "operational busyness" among all the Turing machines in a certain class...

converts into an initial conditional "jump" (goto, branch), followed by 2 tape-action instructions for the "0" case – Print or Erase or None, followed by Left or Right or None, followed by an unconditional "jump" for the "0" case to its next instruction 2 tape-action instructions for the "1" case – Print or Erase or None, followed by Left or Right or None, followed by an unconditional "jump" for the "1" case to its next instruction

for a total of 1 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 1 = 7 instructions per Turing-state.

For example, the 2-state busy beaver's "A" Turing-state, written as two lines of 5-tuples, is:

| Initial m-configuration (Turing state) | Tape symbol | Print operation | Tape motion | Final m-configuration (Turing state) |

| A | 0 | P | R | B |

||||

| A | 1 | P | L | B |

The table represents just a single Turing "instruction", but we see that it consists of two lines of 5-tuples, one for the case "tape symbol under head = 1", the other for the case "tape symbol under head = 0". Turing observed (Undecidable, p. 119) that the left-two columns – "m-configuration" and "symbol" – represent the machine's current "configuration" – its state including both Tape and Table at that instant – and the last three columns are its subsequent "behavior". As the machine cannot be in two "states" at once, the machine must "branch" to either one configuration or the other:

| Initial m-configuration and symbol S | Print operation | Tape motion | Final m-configuration |

| S=0 --> | P --> | R --> | B |

| --> A < | |||

| S=1 --> | P --> | L --> | B |

After the "configuration branch" (J1 xxx) or (J0 xxx) the machine follows one of the two subsequent "behaviors". We list these two behaviors on one line, and number (or label) them sequentially (uniquely). Beneath each jump (branch, go to) we place its jump-to "number" (address, location):

| Initial m-configuration & symbol S | Print operation | Tape motion | Final m-configuration case S=0 | Print operation | Tape motion | Final m-configuration case S=1 | |

| If S=0 then: | P | R | B | ||||

| ---> A < | |||||||

| If S=1 then: | P | L | B | ||||

| | | | | | | |

|||||||

| instruction # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|||||||

| Post–Turing instruction | J1 | P | R | J | P | L | J |

| jump-to instruction # | 5 | B | B |

Per the Post–Turing machine conventions each of the Print, Erase, Left, and Right instructions consist of two actions:

- (i) Tape action: { P, E, L, R}, then

- (ii) Table action: go to next instruction in sequence

And per the Post–Turing machine conventions the conditional "jumps" J0xxx, J1xxx consist of two actions:

- (i) Tape action: look at symbol on tape under the head

- (ii) Table action: If symbol is 0 (1) and J0 (J1) then go to xxx else go to next instruction in sequence

And per the Post–Turing machine conventions the unconditional "jump" Jxxx consists of a single action, or if we want to regularize the 2-action sequence:

- (i) Tape action: look at symbol on tape under the head

- (ii) Table action: If symbol is 0 then go to xxx else if symbol is 1 then go to xxx.

Which, and how many, jumps are necessary? The unconditional jump Jxxx is simply J0 followed immediately by J1 (or vice versa). Wang (1957) also demonstrates that only one conditional jump is required, i.e. either J0xxx or J1xxx. However, with this restriction the machine becomes difficult to write instructions for. Often only two are used, i.e. { J0xxx, J1xxx } { J1xxx, Jxxx } { J0xxx, Jxxx },

but the use of all three { J0xxx, J1xxx, Jxxx } does eliminate extra instructions. In the 2-state Busy Beaver example that we use only { J1xxx, Jxxx }.

2-state Busy Beaver

The mission of the busy beaverBusy beaver

In computability theory, a busy beaver is a Turing machine that attains the maximum "operational busyness" among all the Turing machines in a certain class...

is to print as many ones as possible before halting. The "Print" instruction writes a 1, the "Erase" instruction (not used in this example) writes a 0 (i.e. it is the same as P0). The tape moves "Left" or "Right" (i.e. the "head" is stationary).

State table for a 2-state Turing-machine busy beaver

Busy beaver

In computability theory, a busy beaver is a Turing machine that attains the maximum "operational busyness" among all the Turing machines in a certain class...

:

| Current state A: | Current state B: | |||||

| Write symbol: | Move tape: | Next state: | Write symbol: | Move tape: | Next state: | |

| tape symbol is 0: | 1 | R |

B | 1 | L |

A | ||||

| tape symbol is 1: | 1 | L |

B | 1 | N |

H |

Instructions for the Post–Turing version of a 2-state busy beaver: observe that all the instructions are on the same line and in sequence. This is a significant departure from the "Turing" version and is in the same format as what is called a "computer program":

| Instruction #: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Instruction: | J1 | P | R | J | P | L | J | J1 | P | L | J | P | N | J | H |

|||||||||||||||

| Jump-to #: | 5 | | | 8 | | | 8 | 12 | | | 1 | | | 15 | |

|||||||||||||||

| Turing-state label: | A | | | | | | |

B | | | | | | |

H |

Alternately, we might write the table as a string. The use of "parameter separators" ":" and instruction-separators "," are entirely our choice and do not appear in the model. There are no conventions (but see Booth (1967) p. 374, and Boolos and Jeffrey (1974, 1999) p. 23), for some useful ideas of how to combine state diagram conventions with the instructions – i.e. to use arrows to indicate the destination of the jumps). In the example immediately below, the instructions are sequential starting from "1", and the parameters/"operands" are considered part of their instructions/"opcodes":

- J1:5, P, R, J:8, P, L, J:8, J1:12, P, L, J1:1, P, N, J:15, H

The state diagram of a two-state busy beaver (little drawing, right-hand corner) converts to the equivalent Post–Turing machine with the substitution of 7 Post–Turing instructions per "Turing" state. The HALT instruction adds the 15th state:

Two state busy beaver followed by "tape cleanup"

The following is a two-state Turing busy beaver with additional instructions 15–20 to demonstrate the use of "Erase", J0, etc. These will erase the 1's written by the busy beaver:| Instruction #: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Instruction: | J1 | P | R | J | P | L | J | J1 | P | L | J | P | N | J | L | J0 | E | R | J1 | H |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Jump-to #: | 5 | | | 8 | | | 8 | 12 | | | 1 | | | 15 | | 20 | | | 17 | |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Turing-state label: | A | | | | | | |

B | | | | | | |

* | | | | | |

Additional Post–Turing instructions 15 through 20 erase the symbols created by the busy beaver. These "atomic" instructions are more "efficient" than their Turing-state equivalents (of 7 Post–Turing instructions). To accomplish the same task a Post–Turing machine will (usually) require fewer Post–Turing states than a Turing-machine, because (i) a jump (go-to) can occur to any Post–Turing instruction (e.g. P, E, L, R) within the Turing-state, (ii) a grouping of move-instructions such as L, L, L, P are possible, etc.:

| Instruction #: | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| Instruction: | J0 | E | R | J1 | H |

|||||

| Jump-to #: | 20 | | | 17 | |

Example: Multiply 3 × 4 with a Post–Turing machine

This particular "multiply" algorithm is recursive through two loops. The head moves. It starts to the far left (the top) of the string of unary marks representing a' :

- Move head far right. Establish (i.e. "clear") register c by placing a single blank and then a mark to the right of b

- a_loop: Move head right once, test for the bottom of a' (a blank). If blank then done else erase mark;

- Move head right to b' . Move head right once past the top mark of b' ;

- b_loop: If head is at the bottom of b' (a blank) then move head to far left of a' , else:

-

-

- Erase a mark to locate counter (a blank) in b' .

- Increment c' : Move head right to top of c' and increment c' .

- Move head left to the counter inside b' ,

- Repair counter: print a mark in the blank counter.

- Decrement b' −count: Move head right once.

- Return to b_loop.

-

- Multiply a × b = c, for example: 3 × 4 = 12. The scanned square is indicated by brackets around the mark i.e. [ | ]. An extra mark serves to indicate the symbol "0":

- At the start of the computation a' is 4 unary marks, then a separator blank, b' is 5 unary marks, then a separator mark. An unbounded number of empty spaces must be available for c to the right:

- ....a'.b'.... = : ....[ | ] | | | . | | | | | ....

- At the start of the computation a' is 4 unary marks, then a separator blank, b' is 5 unary marks, then a separator mark. An unbounded number of empty spaces must be available for c to the right:

-

- During the computation the head shuttles back and forth from a' to b' to c' back to b' then to c' , then back to b' , then to c' ad nauseamAd nauseamAd nauseam is a Latin term used to describe an argument which has been continuing "to [the point of] nausea". For example, the sentence, "This topic has been discussed ad nauseam", signifies that the topic in question has been discussed extensively, and that those involved in the discussion have...

while the machine counts through b' and increments c' . Multiplicand a' is slowly counted down (its marks erased – shown for reference with x's below). A "counter" inside b' moves to the right through b (an erased mark shown being read by the head as [ . ] ) but is reconstructed after each pass when the head returns from incrementing c' :- ....a.b.... = : ....xxx | . | | [ . ] | | . | | | | | | | ...

- During the computation the head shuttles back and forth from a' to b' to c' back to b' then to c' , then back to b' , then to c' ad nauseam

-

- At end of computation: c' is 13 marks = "successor of 12" appearing to the right of b' . a' has vanished in process of the computation

- ....b.c = ......... | | | | | . | | | | | | | | | | | | | ...

- At end of computation: c' is 13 marks = "successor of 12" appearing to the right of b' . a' has vanished in process of the computation