Martin A. Pomerantz

Encyclopedia

Martin Arthur Pomerantz was an American physicist who served as Director of the Bartol Research Institute and who had been a leader in developing Antarctic astronomy. When the astronomical observatory at the United States Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station

was opened in 1995, it was named the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory (MAPO) in his honor. Pomerantz published his scientific autobiography, Astronomy on Ice, in 2004.

. He received an M.S. from the University of Pennsylvania

in 1938. In 1938, Pomerantz joined the Bartol Research Foundation, where he spent nearly his entire career. He became a permanent member of the Foundation's scientific staff in 1943. In 1951, he received his Ph.D. in physics from Temple University

for a thesis based on his extensive scientific work at Bartol. In 1959, Pomerantz became the second Director of the Foundation, replacing W. F. G. Swann

upon the latter's retirement.

In 1977, Pomerantz presided over the Foundation's move from its original location at Swarthmore College

to its present location at the University of Delaware

. Despite Pomerantz' efforts, Swarthmore had decided not to renew its 50-year contract with Bartol; there had been a number of conflicts during its decades of residence at Swarthmore. The Foundation was renamed the Bartol Research Institute following the move to Delaware. Pomerantz stepped down as the Institute's president in 1987; he was replaced as president by Norman F. Ness. In 1990, Pomerantz retired, becoming a professor emeritus at the Institute and at the University of Delaware.

Pomerantz had served on the board of trustees for the Franklin Institute

and edited the Journal of the Franklin Institute. He had also served on the editorial board for Space Science Reviews. Pomerantz' scientific papers and documents have been archived at the American Institute of Physics

and at the University of Delaware.

research in the 1940s and 1950s. The initial work was done at the Bartol Institute near Philadelphia. However, the large majority of cosmic rays are charged particles, and the Earth's magnetic field

strongly affects the paths of the these cosmic rays. Since the Earth's magnetic field varies significantly with latitude

, Pomerantz led a number of expeditions measuring cosmic rays from sites at varying latitudes around the Earth. Several of these expeditions were sponsored by the National Geographic Society

. He supervised the installation of a stationary cosmic ray detector facility at Thule Air Base

in Greenland

, and in 1960 Pomerantz installed a cosmic ray detector at McMurdo Station

in Antarctica. Pomerantz' experiments at the South Pole

commenced in 1964.

These experiments and expeditions led to several insights, one of which was an inference about the magnetic field of the sun

. Like the Earth, the sun has a magnetic field. Initial estimates suggested that the sun's magnetic strength was about fifty times that of the Earth. The cosmic ray experiments indicated that the sun's magnetic strength was of the same magnitude as the Earth's; this result is now well-established by many subsequent measurements. The work on the magnetic field of the sun was featured in a 1949 article in Time magazine.

In 1971, Pomerantz published Cosmic Rays, which is a semipopular book that describes cosmic ray observations and the scientific understanding of their origins.

In 1971, Pomerantz published Cosmic Rays, which is a semipopular book that describes cosmic ray observations and the scientific understanding of their origins.

of the Earth means that charged cosmic rays can be detected there without the deflections they experience when detected at lower latitudes. Astronomical observations near the Earth's poles can be done over long periods, without the diurnal variations at lower latitudes. The South Pole is at an altitude of nearly 3000 metres (9,842.5 ft), so the astronomical seeing

should be comparable to other high-altitude observatories; the extreme cold in Antarctica also corresponds to relatively little water vapor in the atmosphere there, which is a particular advantage for infrared astronomy

. Finally, the South Pole lies at the top of a very deep, nearly permanent ice sheet that has been used to advantage in experiments such as the IceCube Neutrino Detector

.

Pomerantz' own research is particularly noted for his development of helioseismology

, which is study of pressure waves in the sun. In 1960, observations of the sun revealed unexpected pulsations in the image. By 1975 it was becoming clear that these pulsations could be understood if the sun was considered as an enormous bell ringing at very low frequencies (one oscillation per minute and lower), and that they provided important insight into the structure of the sun.

In 1979, Pomerantz, along with Eric Fossat and Gerard Grec, conducted the first Antarctic observations by coupling a small telescope with a "sodium vapor resonance cell." The observations were not formally authorized; as Pomerantz later described it, "We had to find a way to convince people that the South Pole was the place for astronomy. Sometimes you need to circumvent the rules. Our bootleg experiment enabled us to obtain the clearest pictures of the sun that had ever been obtained from any place on earth. It proved once and for all this was a superb place for astronomy." Fossat, Grec, and Pomerantz were able to record the sun's vibrations without interruption for more than 100 hours. Their results greatly extended the knowledge of the sun's vibrational frequency spectrum, and they marked the beginning of an extensive astronomy program at the South Pole.

In 1995 the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory was dedicated. In 1999, Norman F. Ness wrote that Pomerantz had "developed and operated instruments in Antarctica for observing similar sun-quake signals in the newly emerging field of helioseismology, a discipline in which he was one of the true pioneers." Pomerantz "also showed tremendous courage, working in Antarctica when it was still a very hazardous proposition."

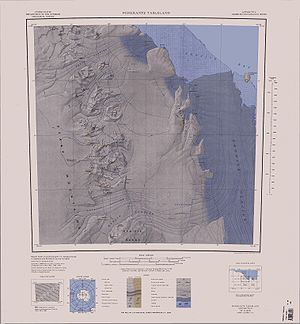

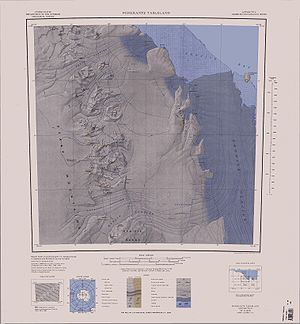

. In 1985, Pomerantz was awarded the Prix de la Belgica.

He received the Distinguished Public Servant Award from the National Science Foundation

in 1987 and the NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal

in 1990. The Pomerantz Tableland, in the Usarp Mountains

of Antarctica, was named after him. In 1995, Pomerantz was honored in Antarctica with the dedication of an observatory bearing his name at the U.S. Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station

. He had received honorary doctorates from Swarthmore College

, University of Uppsala, University of Delaware

, and Syracuse University

. Pomerantz was a fellow of the American Physical Society

, of the American Geophysical Union

, and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

.

Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is the American scientific research station on the high plateau of Antarctica. This station is located at the southernmost place on the Earth, the Geographic South Pole, at an elevation of 2,835 meters above sea level.The original Amundsen-Scott Station was...

was opened in 1995, it was named the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory (MAPO) in his honor. Pomerantz published his scientific autobiography, Astronomy on Ice, in 2004.

Life

Pomerantz was born and raised in New York City, and graduated from Manual Training High School in Brooklyn. In 1937, Pomerantz received an A.B. in physics from Syracuse UniversitySyracuse University

Syracuse University is a private research university located in Syracuse, New York, United States. Its roots can be traced back to Genesee Wesleyan Seminary, founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1832, which also later founded Genesee College...

. He received an M.S. from the University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania is a private, Ivy League university located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Penn is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States,Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution...

in 1938. In 1938, Pomerantz joined the Bartol Research Foundation, where he spent nearly his entire career. He became a permanent member of the Foundation's scientific staff in 1943. In 1951, he received his Ph.D. in physics from Temple University

Temple University

Temple University is a comprehensive public research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Originally founded in 1884 by Dr. Russell Conwell, Temple University is among the nation's largest providers of professional education and prepares the largest body of professional...

for a thesis based on his extensive scientific work at Bartol. In 1959, Pomerantz became the second Director of the Foundation, replacing W. F. G. Swann

William Francis Gray Swann

William Francis Gray Swann was an Anglo-American physicist. He was educated at Brighton Technical College and the Royal College of Science from which he obtained a B.Sc. in 1905. He worked as an Assistant Lecturer at the University of Sheffield, while simultaneously pursuing a doctorate at...

upon the latter's retirement.

In 1977, Pomerantz presided over the Foundation's move from its original location at Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College is a private, independent, liberal arts college in the United States with an enrollment of about 1,500 students. The college is located in the borough of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, 11 miles southwest of Philadelphia....

to its present location at the University of Delaware

University of Delaware

The university is organized into seven colleges:* College of Agriculture and Natural Resources* College of Arts and Sciences* Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics* College of Earth, Ocean and Environment* College of Education and Human Development...

. Despite Pomerantz' efforts, Swarthmore had decided not to renew its 50-year contract with Bartol; there had been a number of conflicts during its decades of residence at Swarthmore. The Foundation was renamed the Bartol Research Institute following the move to Delaware. Pomerantz stepped down as the Institute's president in 1987; he was replaced as president by Norman F. Ness. In 1990, Pomerantz retired, becoming a professor emeritus at the Institute and at the University of Delaware.

Pomerantz had served on the board of trustees for the Franklin Institute

Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and one of the oldest centers of science education and development in the United States, dating to 1824. The Institute also houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memorial.-History:On February 5, 1824, Samuel Vaughn Merrick and...

and edited the Journal of the Franklin Institute. He had also served on the editorial board for Space Science Reviews. Pomerantz' scientific papers and documents have been archived at the American Institute of Physics

American Institute of Physics

The American Institute of Physics promotes science, the profession of physics, publishes physics journals, and produces publications for scientific and engineering societies. The AIP is made up of various member societies...

and at the University of Delaware.

Cosmic ray research

Pomerantz was one of the pioneers in balloon-borne cosmic rayCosmic ray

Cosmic rays are energetic charged subatomic particles, originating from outer space. They may produce secondary particles that penetrate the Earth's atmosphere and surface. The term ray is historical as cosmic rays were thought to be electromagnetic radiation...

research in the 1940s and 1950s. The initial work was done at the Bartol Institute near Philadelphia. However, the large majority of cosmic rays are charged particles, and the Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field is the magnetic field that extends from the Earth's inner core to where it meets the solar wind, a stream of energetic particles emanating from the Sun...

strongly affects the paths of the these cosmic rays. Since the Earth's magnetic field varies significantly with latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

, Pomerantz led a number of expeditions measuring cosmic rays from sites at varying latitudes around the Earth. Several of these expeditions were sponsored by the National Geographic Society

National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society , headquartered in Washington, D.C. in the United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational institutions in the world. Its interests include geography, archaeology and natural science, the promotion of environmental and historical...

. He supervised the installation of a stationary cosmic ray detector facility at Thule Air Base

Thule Air Base

Thule Air Base or Thule Air Base/Pituffik Airport , is the United States Air Force's northernmost base, located north of the Arctic Circle and from the North Pole on the northwest side of the island of Greenland. It is approximately east of the North Magnetic Pole.-Overview:Thule Air Base is the...

in Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

, and in 1960 Pomerantz installed a cosmic ray detector at McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station

McMurdo Station is a U.S. Antarctic research center located on the southern tip of Ross Island, which is in the New Zealand-claimed Ross Dependency on the shore of McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. It is operated by the United States through the United States Antarctic Program, a branch of the National...

in Antarctica. Pomerantz' experiments at the South Pole

South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

commenced in 1964.

These experiments and expeditions led to several insights, one of which was an inference about the magnetic field of the sun

Solar dynamo

The solar dynamo is the physical process that generates the Sun's magnetic field. The Sun is permeated by an overall dipole magnetic field, as are many other celestial bodies such as the Earth. The dipole field is produced by a circular electric current flowing deep within the star, following...

. Like the Earth, the sun has a magnetic field. Initial estimates suggested that the sun's magnetic strength was about fifty times that of the Earth. The cosmic ray experiments indicated that the sun's magnetic strength was of the same magnitude as the Earth's; this result is now well-established by many subsequent measurements. The work on the magnetic field of the sun was featured in a 1949 article in Time magazine.

Antarctic astronomy and astrophysics

Pomerantz saw the potential of the South Pole as an observing platform remarkably early. Its proximity to the South magnetic poleSouth Magnetic Pole

The Earth's South Magnetic Pole is the wandering point on the Earth's surface where the geomagnetic field lines are directed vertically upwards...

of the Earth means that charged cosmic rays can be detected there without the deflections they experience when detected at lower latitudes. Astronomical observations near the Earth's poles can be done over long periods, without the diurnal variations at lower latitudes. The South Pole is at an altitude of nearly 3000 metres (9,842.5 ft), so the astronomical seeing

Astronomical seeing

Astronomical seeing refers to the blurring and twinkling of astronomical objects such as stars caused by turbulent mixing in the Earth's atmosphere varying the optical refractive index...

should be comparable to other high-altitude observatories; the extreme cold in Antarctica also corresponds to relatively little water vapor in the atmosphere there, which is a particular advantage for infrared astronomy

Infrared astronomy

Infrared astronomy is the branch of astronomy and astrophysics that studies astronomical objects visible in infrared radiation. The wavelength of infrared light ranges from 0.75 to 300 micrometers...

. Finally, the South Pole lies at the top of a very deep, nearly permanent ice sheet that has been used to advantage in experiments such as the IceCube Neutrino Detector

IceCube Neutrino Detector

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory is a neutrino telescope constructed at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica...

.

Pomerantz' own research is particularly noted for his development of helioseismology

Helioseismology

Helioseismology is the study of the propagation of wave oscillations, particularly acoustic pressure waves, in the Sun. Unlike seismic waves on Earth, solar waves have practically no shear component . Solar pressure waves are believed to be generated by the turbulence in the convection zone near...

, which is study of pressure waves in the sun. In 1960, observations of the sun revealed unexpected pulsations in the image. By 1975 it was becoming clear that these pulsations could be understood if the sun was considered as an enormous bell ringing at very low frequencies (one oscillation per minute and lower), and that they provided important insight into the structure of the sun.

In 1979, Pomerantz, along with Eric Fossat and Gerard Grec, conducted the first Antarctic observations by coupling a small telescope with a "sodium vapor resonance cell." The observations were not formally authorized; as Pomerantz later described it, "We had to find a way to convince people that the South Pole was the place for astronomy. Sometimes you need to circumvent the rules. Our bootleg experiment enabled us to obtain the clearest pictures of the sun that had ever been obtained from any place on earth. It proved once and for all this was a superb place for astronomy." Fossat, Grec, and Pomerantz were able to record the sun's vibrations without interruption for more than 100 hours. Their results greatly extended the knowledge of the sun's vibrational frequency spectrum, and they marked the beginning of an extensive astronomy program at the South Pole.

In 1995 the Martin A. Pomerantz Observatory was dedicated. In 1999, Norman F. Ness wrote that Pomerantz had "developed and operated instruments in Antarctica for observing similar sun-quake signals in the newly emerging field of helioseismology, a discipline in which he was one of the true pioneers." Pomerantz "also showed tremendous courage, working in Antarctica when it was still a very hazardous proposition."

Honors

In 1970 Pomerantz received a Centennial Medal from Syracuse UniversitySyracuse University

Syracuse University is a private research university located in Syracuse, New York, United States. Its roots can be traced back to Genesee Wesleyan Seminary, founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1832, which also later founded Genesee College...

. In 1985, Pomerantz was awarded the Prix de la Belgica.

He received the Distinguished Public Servant Award from the National Science Foundation

National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation is a United States government agency that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National Institutes of Health...

in 1987 and the NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal

NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal

The NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Medal was established by NASA on September 15, 1961 when the original ESM was divided into three separate awards. Under the current guidelines, the ESAM is awarded for unusually significant scientific contribution toward achievement of aeronautical or...

in 1990. The Pomerantz Tableland, in the Usarp Mountains

Usarp Mountains

The Usarp Mountains is a major Antarctic mountain range, lying westward of the Rennick Glacier and trending N-S for about . The feature is bounded to the north by Pryor Glacier and the Wilson Hills...

of Antarctica, was named after him. In 1995, Pomerantz was honored in Antarctica with the dedication of an observatory bearing his name at the U.S. Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station

Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station is the American scientific research station on the high plateau of Antarctica. This station is located at the southernmost place on the Earth, the Geographic South Pole, at an elevation of 2,835 meters above sea level.The original Amundsen-Scott Station was...

. He had received honorary doctorates from Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College is a private, independent, liberal arts college in the United States with an enrollment of about 1,500 students. The college is located in the borough of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, 11 miles southwest of Philadelphia....

, University of Uppsala, University of Delaware

University of Delaware

The university is organized into seven colleges:* College of Agriculture and Natural Resources* College of Arts and Sciences* Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics* College of Earth, Ocean and Environment* College of Education and Human Development...

, and Syracuse University

Syracuse University

Syracuse University is a private research university located in Syracuse, New York, United States. Its roots can be traced back to Genesee Wesleyan Seminary, founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1832, which also later founded Genesee College...

. Pomerantz was a fellow of the American Physical Society

American Physical Society

The American Physical Society is the world's second largest organization of physicists, behind the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft. The Society publishes more than a dozen scientific journals, including the world renowned Physical Review and Physical Review Letters, and organizes more than 20...

, of the American Geophysical Union

American Geophysical Union

The American Geophysical Union is a nonprofit organization of geophysicists, consisting of over 50,000 members from over 135 countries. AGU's activities are focused on the organization and dissemination of scientific information in the interdisciplinary and international field of geophysics...

, and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science is an international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific responsibility, and supporting scientific education and science outreach for the...

.