William Z. Ripley

Encyclopedia

William Zebina Ripley was an American economist

, lecturer at Columbia University, professor of economics at MIT, professor of political economics at Harvard University, and racial theorist. Ripley was famous for his criticisms of American railroad economics and American business practices in the 1920s and 1930s and later his tripartite racial theory of Europe. His work of racial anthropology was later taken up by physical anthropologists, eugenicists

and white nationalists.

in 1867 to Nathaniel L. Ripley and Estimate R.E. Baldwin Ripley. He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

for his undergraduate education in engineering, graduating in 1890, and received a master's and doctorate degree from Columbia University

in 1892 and 1893 respectively. In 1893, he was married to Ida S. Davis. From 1893 until 1901, Ripley lectured on sociology at Columbia University and from 1895 until 1901 he was a professor of economics at MIT. From 1901 onwards, he was a professor of political economics at Harvard University

. He was a corresponding member of the Anthropological Society of Paris, the Roman Anthropological Society, the Cherbourg Society of Natural Sciences, and in 1898 and 1900-1901, the vice president of the American Economic Association

.

In 1899, he authored a book entitled The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study

In 1899, he authored a book entitled The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study

, which had grown out of a series of lectures he had given at the Lowell Institute at Columbia in 1896. Ripley believed that race was the central engine to understanding human history. However, his work also afforded strong weight to environmental and non-biological factors, such as traditions. He believed, as he wrote in the introduction to Races of Europe, that:

Ripley's book, written to help finance his children's education, became a very-well respected work of anthropology, renowned for its careful writing, compilation, and criticism of the data of many other anthropologists in Europe

and the United States

.

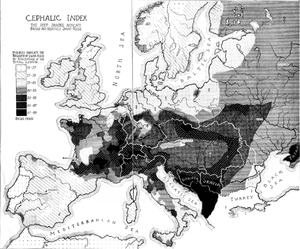

Ripley based his conclusions about race by correlating anthropometric

data with geographical data, paying special attention to the use of the cephalic index

, which at the time was one of the most consistent anthropometric measurements. From this and other socio-geographical factors, Ripley classified Europeans into three distinct races:

Ripley also considered that "Africa begins beyond the Pyrenees", as he wrote in page 272 :

Ripley's tripartite system of race put him at odds both with other scholars who insisted that there was only one European race, and those who insisted that there were dozens of European races (such as Joseph Deniker

, who Ripley saw as his chief rival). Ripley was the first American recipient of the Huxley Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1908 on account of his contributions to anthropology.

The Races of Europe, overall, became an influential book of the Progressive Era

in the field of racial taxonomy. Ripley's tripartite system was especially championed by Madison Grant

, who changed Ripley's "Teutonic" type into Grant's own Nordic type (taking the name, but little else, from Deniker), which he postulated as a master race

. It is in this light that Ripley's work on race is usually remembered today, though little of Grant's ideology is present in Ripley's original work.

Ripley worked under Theodore Roosevelt

Ripley worked under Theodore Roosevelt

on the United States Industrial Commission in 1900, helping negotiate relations between railway companies and anthracite coal

companies. He served on the Eight Hour Commission in 1916, adjusting railway wages to the new eight-hour workday. From 1917 to 1918, he served as Administrator of Labor Standards for the United States Department of War

, and helped to settle railway strikes.

Ripley was the Vice President of the American Economics Association 1898, 1900, and 1901, and was elected president of it in 1933. From 1919 to 1920, he served as the chairman of the National Adjustment Commission of the United States Shipping Board, and from 1920 to 1923, he served with the Interstate Commerce Commission

. In 1921, he was ICC special examiner on the construction of railroads. There, he wrote the ICC's plan for the regional consolidation of U.S. railways, which became known as the Ripley Plan. In 1929, the ICC published Ripley's Plan under the title Complete Plan of Consolidation. Numerous hearings were held by the ICC regarding the plan under the topic of "In the Matter of Consolidation of the Railways of the United States into a Limited Number of Systems".

Starting with a series of articles in the Atlantic Monthly in 1925 under the headlines of "Stop, Look, Listen!", Ripley became a major critic of American corporate practices. In 1926, he issued a well-circulated critique of Wall Street

's practices of speculation

and secrecy

. He received a full-page profile in the New York Times with the headline, "When Ripley Speaks, Wall Street Heeds". According to Time

magazine, Ripley became widely known as "The Professor Who Jarred Wall Street".

However, after an automobile accident in January 1927, Ripley suffered a nervous breakdown

and was forced to recuperate at a sanitarium

in Connecticut

. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929

, he was occasionally credited with having predicted the financial disaster. In December 1929, the New York Times said:

He was unable to return to teaching until at least 1929. However, in the early 1930s, he continued to issue criticisms of the railroad industry labor practices. In 1931, he had also testified at a Senate

banking inquiry, urging the curbing of investment trusts. In 1932, he appeared at the Senate Banking and Currency Committee, and demanded public inquiry into the financial affairs of corporations and authored a series of articles in the New York Times stressing the importance of railroad economics to the country's economy. Yet, by the end of the year he had suffered another nervous breakdown, and retired in early 1933.

Ripley died in 1941 at his summer home in East Edgecomb

, Maine

. An obituary in the New York Times implied that Ripley had predicted the 1929 crash with his "fearless exposés" of Wall Street practices, in particular his pronouncement that:

His book, Railway Problems: An Early History of Competition, Rates and Regulations, was republished in 2000 as part of a "Business Classic" series.

Economist

An economist is a professional in the social science discipline of economics. The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy...

, lecturer at Columbia University, professor of economics at MIT, professor of political economics at Harvard University, and racial theorist. Ripley was famous for his criticisms of American railroad economics and American business practices in the 1920s and 1930s and later his tripartite racial theory of Europe. His work of racial anthropology was later taken up by physical anthropologists, eugenicists

Eugenics

Eugenics is the "applied science or the bio-social movement which advocates the use of practices aimed at improving the genetic composition of a population", usually referring to human populations. The origins of the concept of eugenics began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance,...

and white nationalists.

Biography

William Z. Ripley was born in Medford, MassachusettsMedford, Massachusetts

Medford is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, in the United States, on the Mystic River, five miles northwest of downtown Boston. In the 2010 U.S. Census, Medford's population was 56,173...

in 1867 to Nathaniel L. Ripley and Estimate R.E. Baldwin Ripley. He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

for his undergraduate education in engineering, graduating in 1890, and received a master's and doctorate degree from Columbia University

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

in 1892 and 1893 respectively. In 1893, he was married to Ida S. Davis. From 1893 until 1901, Ripley lectured on sociology at Columbia University and from 1895 until 1901 he was a professor of economics at MIT. From 1901 onwards, he was a professor of political economics at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

. He was a corresponding member of the Anthropological Society of Paris, the Roman Anthropological Society, the Cherbourg Society of Natural Sciences, and in 1898 and 1900-1901, the vice president of the American Economic Association

American Economic Association

The American Economic Association, or AEA, is a learned society in the field of economics, headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. It publishes one of the most prestigious academic journals in economics: the American Economic Review...

.

The Races of Europe

The Races of Europe

The Races of Europe is the title of two anthropological publications*The Races of Europe by William Z. Ripley*The Races of Europe by Carleton S. Coon...

, which had grown out of a series of lectures he had given at the Lowell Institute at Columbia in 1896. Ripley believed that race was the central engine to understanding human history. However, his work also afforded strong weight to environmental and non-biological factors, such as traditions. He believed, as he wrote in the introduction to Races of Europe, that:

- "Race, properly speaking, is responsible only for those peculiarities, mental or bodily, which are transmitted with constancy along the lines of direct physical descent from father to son. Many mental traits, aptitudes, or proclivities, on the other hand, which reappear persistently in successive populations may be derived from an entirely different source. They may have descended collaterally, along the lines of purely mental suggestion by virtue of mere social contact with preceding generations."

Ripley's book, written to help finance his children's education, became a very-well respected work of anthropology, renowned for its careful writing, compilation, and criticism of the data of many other anthropologists in Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

.

Ripley based his conclusions about race by correlating anthropometric

Anthropometry

Anthropometry refers to the measurement of the human individual...

data with geographical data, paying special attention to the use of the cephalic index

Cephalic index

Cephalic index is the ratio of the maximum width of the head multiplied by 100 divided by its maximum length ....

, which at the time was one of the most consistent anthropometric measurements. From this and other socio-geographical factors, Ripley classified Europeans into three distinct races:

- Teutonic — members of the northern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), tall in stature, and possessed pale eyes and skin.

- AlpineAlpine raceThe Alpine race is an historical racial classification or sub-race of humans, considered a branch of the Caucasian race. The term is not commonly used today, but was popular in the early 20th century.-History:...

— members of the central race were round-skulled (or brachycephalic), stocky in stature, and possessed intermediate eye and skin color. - MediterraneanMediterranean raceThe Mediterranean race was one of the three sub-categories into which the Caucasian race and the people of Europe were divided by anthropologists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, following the publication of William Z. Ripley's book The Races of Europe...

— members of the southern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), short in stature, and possessed dark eyes and skin.

Ripley also considered that "Africa begins beyond the Pyrenees", as he wrote in page 272 :

- " Beyond the Pyrenees begins Africa. Once that natural barrier is crossed, the Mediterranean racial type in all its purity confronts us. The human phenomena is entirely parallel with the sudden transition to the flora and fauna of the south. The Iberian population thus isolated from the rest of Europe, are allied in all important anthropological respects with the peoples inhabiting Africa north of the Sahara, from the Red Sea to the Atlantic."

Ripley's tripartite system of race put him at odds both with other scholars who insisted that there was only one European race, and those who insisted that there were dozens of European races (such as Joseph Deniker

Joseph Deniker

Joseph Deniker was a French naturalist and anthropologist, known primarily for his attempts to develop highly-detailed maps of race in Europe.- Life :...

, who Ripley saw as his chief rival). Ripley was the first American recipient of the Huxley Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1908 on account of his contributions to anthropology.

The Races of Europe, overall, became an influential book of the Progressive Era

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political...

in the field of racial taxonomy. Ripley's tripartite system was especially championed by Madison Grant

Madison Grant

Madison Grant was an American lawyer, historian and physical anthropologist, known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist...

, who changed Ripley's "Teutonic" type into Grant's own Nordic type (taking the name, but little else, from Deniker), which he postulated as a master race

Master race

Master race was a phrase and concept originating in the slave-holding Southern US. The later phrase Herrenvolk , interpreted as 'master race', was a concept in Nazi ideology in which the Nordic peoples, one of the branches of what in the late-19th and early-20th century was called the Aryan race,...

. It is in this light that Ripley's work on race is usually remembered today, though little of Grant's ideology is present in Ripley's original work.

Economics

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

on the United States Industrial Commission in 1900, helping negotiate relations between railway companies and anthracite coal

Anthracite coal

Anthracite is a hard, compact variety of mineral coal that has a high luster...

companies. He served on the Eight Hour Commission in 1916, adjusting railway wages to the new eight-hour workday. From 1917 to 1918, he served as Administrator of Labor Standards for the United States Department of War

United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department , was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army...

, and helped to settle railway strikes.

Ripley was the Vice President of the American Economics Association 1898, 1900, and 1901, and was elected president of it in 1933. From 1919 to 1920, he served as the chairman of the National Adjustment Commission of the United States Shipping Board, and from 1920 to 1923, he served with the Interstate Commerce Commission

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission was a regulatory body in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers, including...

. In 1921, he was ICC special examiner on the construction of railroads. There, he wrote the ICC's plan for the regional consolidation of U.S. railways, which became known as the Ripley Plan. In 1929, the ICC published Ripley's Plan under the title Complete Plan of Consolidation. Numerous hearings were held by the ICC regarding the plan under the topic of "In the Matter of Consolidation of the Railways of the United States into a Limited Number of Systems".

Starting with a series of articles in the Atlantic Monthly in 1925 under the headlines of "Stop, Look, Listen!", Ripley became a major critic of American corporate practices. In 1926, he issued a well-circulated critique of Wall Street

Wall Street

Wall Street refers to the financial district of New York City, named after and centered on the eight-block-long street running from Broadway to South Street on the East River in Lower Manhattan. Over time, the term has become a metonym for the financial markets of the United States as a whole, or...

's practices of speculation

Speculation

In finance, speculation is a financial action that does not promise safety of the initial investment along with the return on the principal sum...

and secrecy

Secrecy

Secrecy is the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups, perhaps while sharing it with other individuals...

. He received a full-page profile in the New York Times with the headline, "When Ripley Speaks, Wall Street Heeds". According to Time

Time (magazine)

Time is an American news magazine. A European edition is published from London. Time Europe covers the Middle East, Africa and, since 2003, Latin America. An Asian edition is based in Hong Kong...

magazine, Ripley became widely known as "The Professor Who Jarred Wall Street".

However, after an automobile accident in January 1927, Ripley suffered a nervous breakdown

Nervous breakdown

Mental breakdown is a non-medical term used to describe an acute, time-limited phase of a specific disorder that presents primarily with features of depression or anxiety.-Definition:...

and was forced to recuperate at a sanitarium

Sanatorium

A sanatorium is a medical facility for long-term illness, most typically associated with treatment of tuberculosis before antibiotics...

in Connecticut

Connecticut

Connecticut is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, and the state of New York to the west and the south .Connecticut is named for the Connecticut River, the major U.S. river that approximately...

. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 , also known as the Great Crash, and the Stock Market Crash of 1929, was the most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States, taking into consideration the full extent and duration of its fallout...

, he was occasionally credited with having predicted the financial disaster. In December 1929, the New York Times said:

- "Three years ago [Ripley] spoke some plain words about Wall Street. An automobile crash and a nervous breakdown followed. A few weeks ago Wall Street had its crash and breakdown. Now Professor Ripley is preparing to return to his Harvard classes next February."

He was unable to return to teaching until at least 1929. However, in the early 1930s, he continued to issue criticisms of the railroad industry labor practices. In 1931, he had also testified at a Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

banking inquiry, urging the curbing of investment trusts. In 1932, he appeared at the Senate Banking and Currency Committee, and demanded public inquiry into the financial affairs of corporations and authored a series of articles in the New York Times stressing the importance of railroad economics to the country's economy. Yet, by the end of the year he had suffered another nervous breakdown, and retired in early 1933.

Ripley died in 1941 at his summer home in East Edgecomb

Edgecomb, Maine

Edgecomb is a town in Lincoln County, Maine, United States. The population was 1,090 at the 2000 census. The town was named for Lord Edgecomb, a supporter of the colonists...

, Maine

Maine

Maine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost...

. An obituary in the New York Times implied that Ripley had predicted the 1929 crash with his "fearless exposés" of Wall Street practices, in particular his pronouncement that:

- "Prosperity, not real but specious, may indeed be unduly protracted by artificial means, but in the end truth is bound to prevail."

His book, Railway Problems: An Early History of Competition, Rates and Regulations, was republished in 2000 as part of a "Business Classic" series.