Wilfrid Noyce

Encyclopedia

Cuthbert Wilfrid Francis Noyce (31 December 1917 – 24 July 1962) (usually known as Wilfrid Noyce (often misspelt as 'Wilfred'), some sources give third forename as Frank) was an English

mountaineer

and author

. He was a member of the 1953 British Expedition that made the first ascent

of Mount Everest

.

Noyce was born in 1917 in Simla

Noyce was born in 1917 in Simla

, the British hill station in India

. The eldest son of Sir Frank Noyce of the Indian Civil Service and his wife, Enid Isabel, a daughter of W. M. Kirkus of Liverpool

, Noyce was educated at Charterhouse

, where he became head boy, and King's College

, Cambridge, taking a first in Modern Languages.

In World War II

, he was initially a conscientious objector

, joining the Friends Ambulance Unit. However, he later chose to serve as a private in the Welsh Guards

, before being commissioned as a second lieutenant

in the King's Royal Rifle Corps

on 19 July 1941. He later attained the rank of captain in the Intelligence Corps; John Hunt

wrote that "...during a part of the war [Noyce] was employed in training air crews [in mountain techniques] in Kashmir

. For a brief period he assisted me in running a similar course for soldiers". He was also employed as a code-breaker, managing to break an important Japanese code.

After the war, Noyce became a schoolmaster. From 1946 until 1950 he taught modern languages at Malvern College

. Then, following in the footsteps of George Mallory

, he returned as a master to his own old school, Charterhouse, where he remained for ten years. On 12 August 1950, between Malvern and Charterhouse, he married Rosemary Campbell Davies, and they had two sons, Michael and Jeremy.

By the age of eighteen, Noyce was already a fine climber, from 1935 regularly climbing with John Menlove Edwards

By the age of eighteen, Noyce was already a fine climber, from 1935 regularly climbing with John Menlove Edwards

of Liverpool. Before World War II, he helped Edwards to produce rock climbing guides to the crags of Tryfan

and Lliwedd

in Snowdonia

. Like other leading British climbers of the pre-World War II period, such as Mallory, Jack Longland

, Ivan Waller and A. B. Hargreaves, Noyce became a protégé of Geoffrey Winthrop Young

, attending his parties at Pen-y-Pass

.

In the late 1930s, Noyce was one of a small band of Britons climbing at high standards in the Alps

. He was well known for his speed and stamina, and in two early alpine seasons, 1937 and 1938, climbing with Armand Charlet or Hans Brantschen as his guide

, he made major climbs in very fast times. In 1942, in North Wales, he achieved a non-stop solo climb of 1,370 metres. During this period Noyce wrote that he suffered three serious accidents:

The first fall refers to an incident when he was held on the rope by Edwards after falling, despite damage to the rope.

Edmund Hillary

, meeting Noyce for the first time as the expedition assembled in Nepal

, echoed Hunt's praise: "Wilf Noyce was a tough and experienced mountaineer with an impressive record of difficult and dangerous climbs. In many respects I considered Noyce the most competent British climber I had met."

At the initial meeting of the Everest team at the premises of the Royal Geographical Society

on 17 November 1952, Noyce was designated as being charge of writing (meaning the dispatches that were to be sent home from the mountain) and "volunteered to help with the packing" (he aided Stuart Bain with this). On the walk-in to the mountain, Noyce, together with Charles Evans, who had been designated as in charge of stores at the RGS meeting, were designated as the "baggage party", in charge of the clothing and equipment for the approach. Noyce was also in charge of mountaineering equipment on the ascent itself, having been instructed in the repair of high-altitude boots ("I had worked for three days with Robert Lawrie

's bootmakers, learning chiefly how to stick on micro-cellular rubber soles and heels"). Noyce's skills in boot repair were in demand on the ascent; according to Charles Wylie, the thin Vibram

soles that were used on the boots often peeled off at the toes but Noyce "saved the situation with some really professional repair work".

Together with George Lowe

, on 17 May Noyce established Camp VII on the Lhotse

face of Everest. On 20 May he radioed to Hunt that many of the oxygen bottles (the training or Utility model, not the type that were to be used on the summit attempt) that had been ferried up to Camp VII were leaking. Hunt noted "Wilfrid, though gifted in more ways than one, has not a marked mechanical bent and we hoped his tests were not conclusive. Tom

, however, had a luring fear that these very tests, carried out by a possibly anoxic

Wilfrid, might have resulted in the discharging of all nine cylinders".

Annullu (the younger brother of Da Tensing) were the first members of the expedition to reach Everest's South Col

, after what Noyce said was "one of the most enjoyable days' mountaineering I've ever had". They left Camp VII at 9.30 am, both using oxygen; according to Noyce, "I had told Anullu that we would not start too early, for fear of frostbite

." Several hours later they reached the highest point attained by the British expedition to date: "an aluminium piton with a great coil of thick rope" left by George Lowe and party. The climbers in the camps below, according to Hunt, were watching their progress on this vital part of the climb; by early afternoon "their speed had noticeably increased and our excitement soon grew to amazement when it dawned on us that Noyce and Annullu were heading for the South Col itself".

Not long after Hunt made that observation, they reached the Col.

In a passage in South Col, Noyce's book of the expedition published the following year, he gives an account of the scene that greeted him at the Col:

From the remains of the Swiss expedition

Noyce "picked up some Vita-Weat, a tin of sardines and a box of matches, all in perfect condition after lying exposed to the elements for over six months". Noyce and Annullu fixed a 500-ft length of nylon rope to protect the steep slopes leading up to the Col where Camp VIII was to be established ("this was to be a moral lifeline for weary Sherpas returning from the long carry"), and then descended to Camp VII which they reached at 5.30 pm. From a mountaineering perspective, as Everest veteran Chris Bonington

wrote, "[Noyce] had fulfilled his role in John Hunt's master plan, had established one vital stepping-stone for others to achieve the final goal."

According to Hunt, the climbing team had been in low spirits before Noyce and Annullu reached the South Col, but the effect of their safe return from the Col to Camp VII "had a profound impression on the waiting men. If these two could do it, so could they [...] Morale rose suddenly, inspired by fine example".

Noyce climbed up to the South Col a second time during the ascent; on 29 May, the day of the successful first ascent, he set out with three Sherpas from Camp VII, reaching the Col with one of them, Pasang Phutar, later that day; they "had each carried a double load—at least 50 lb.—from the point where the two other Sherpas had given up". Hunt noted that "Noyce and Wylie were the only two members of the climbing party to reach the South Col without oxygen."

Pasang, George Lowe and Noyce met the successful summit team of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay

at the Col, giving the tired climbers drinks and congratulations. It was here, 200 metres above the camp, that Hillary told Lowe, who had gone out to greet them, "Well, we knocked the bastard off." Hillary wrote: "Wilf Noyce and Pasang Puta [sic] were also in Camp and they looked after us with patience and kindness. I felt a moment of sympathy for Wilf – he was the only one left with the strength to try for the summit; but now he wouldn't get the chance. It was another foul night with strong wind and very cold temperatures ..." Noyce descended the following day with Hillary, Tenzing, Lowe and Pasang Phutar, reaching Camp IV on 30 May.

As well as naming his book of the expedition South Col, Noyce also wrote a poem called 'South Col'.

On 20 May 1957, together with A. D. M. Cox, Noyce made the effective first ascent of Machapuchare

On 20 May 1957, together with A. D. M. Cox, Noyce made the effective first ascent of Machapuchare

(6,993 m) in the Annapurna

Himal, reaching to within 50 m of the summit before turning back at that point out of respect for local religious beliefs. Noyce and Cox also made the first ascent – via the north-east face – of Singu Chuli

(Fluted Peak) (6,501 m) on 13 June 1957. On 5 August 1959 Noyce, together with C. J. Mortlock and Jack Sadler, made the first British ascent of the Welzenbach route on the north face of the Dent d'Hérens

. Some days later, on 15–16 August, the same party made the first British ascent of the north-east face of the Signalkuppe

, the longest and most serious route on the east face of Monte Rosa

.

Noyce made the first ascent of Trivor

Noyce made the first ascent of Trivor

(7,577 m) in Pakistan's Hispar Muztagh

range in 1960 together with Jack Sadler.

Noyce died in a mountaineering accident together with the 23-year-old Scot Robin Smith

in 1962 after a successful ascent of Mount Garmo

(6,595 m), in the Pamirs. On the descent, one of Smith or Noyce slipped on a layer of soft snow over ice, pulling the other, and they both fell 4,000 feet.

, Petrarch

, Rousseau

, Ferdinand de Saussure

, Goethe, Wordsworth

, Keats

, Ruskin

, Leslie Stephen

, Nietzsche

, Pope Pius XI

and Robert Falcon Scott

. In the introduction Noyce says that he chose these figures because:

, Surrey

– where Charterhouse

is located – is named after him.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

mountaineer

Mountaineering

Mountaineering or mountain climbing is the sport, hobby or profession of hiking, skiing, and climbing mountains. While mountaineering began as attempts to reach the highest point of unclimbed mountains it has branched into specialisations that address different aspects of the mountain and consists...

and author

Author

An author is broadly defined as "the person who originates or gives existence to anything" and that authorship determines responsibility for what is created. Narrowly defined, an author is the originator of any written work.-Legal significance:...

. He was a member of the 1953 British Expedition that made the first ascent

First ascent

In climbing, a first ascent is the first successful, documented attainment of the top of a mountain, or the first to follow a particular climbing route...

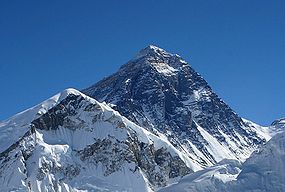

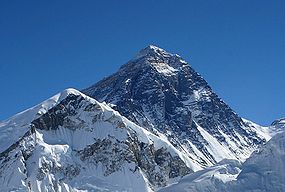

of Mount Everest

Mount Everest

Mount Everest is the world's highest mountain, with a peak at above sea level. It is located in the Mahalangur section of the Himalayas. The international boundary runs across the precise summit point...

.

Life and family

Shimla

Shimla , formerly known as Simla, is the capital city of Himachal Pradesh. In 1864, Shimla was declared the summer capital of the British Raj in India. A popular tourist destination, Shimla is often referred to as the "Queen of Hills," a term coined by the British...

, the British hill station in India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

. The eldest son of Sir Frank Noyce of the Indian Civil Service and his wife, Enid Isabel, a daughter of W. M. Kirkus of Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

, Noyce was educated at Charterhouse

Charterhouse School

Charterhouse School, originally The Hospital of King James and Thomas Sutton in Charterhouse, or more simply Charterhouse or House, is an English collegiate independent boarding school situated at Godalming in Surrey.Founded by Thomas Sutton in London in 1611 on the site of the old Carthusian...

, where he became head boy, and King's College

King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college's full name is "The King's College of our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge", but it is usually referred to simply as "King's" within the University....

, Cambridge, taking a first in Modern Languages.

In World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, he was initially a conscientious objector

Conscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, and/or religion....

, joining the Friends Ambulance Unit. However, he later chose to serve as a private in the Welsh Guards

Welsh Guards

The Welsh Guards is an infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Guards Division.-Creation :The Welsh Guards came into existence on 26 February 1915 by Royal Warrant of His Majesty King George V in order to include Wales in the national component to the Foot Guards, "..though the order...

, before being commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

in the King's Royal Rifle Corps

King's Royal Rifle Corps

The King's Royal Rifle Corps was a British Army infantry regiment, originally raised in colonial North America as the Royal Americans, and recruited from American colonists. Later ranked as the 60th Regiment of Foot, the regiment served for more than 200 years throughout the British Empire...

on 19 July 1941. He later attained the rank of captain in the Intelligence Corps; John Hunt

John Hunt, Baron Hunt

Brigadier Henry Cecil John Hunt, Baron Hunt KG, PC, CBE, DSO, was a British army officer who is best known as the leader of the successful 1953 British Expedition to Mount Everest.-Early life and career:...

wrote that "...during a part of the war [Noyce] was employed in training air crews [in mountain techniques] in Kashmir

Kashmir

Kashmir is the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term Kashmir geographically denoted only the valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal mountain range...

. For a brief period he assisted me in running a similar course for soldiers". He was also employed as a code-breaker, managing to break an important Japanese code.

After the war, Noyce became a schoolmaster. From 1946 until 1950 he taught modern languages at Malvern College

Malvern College

Malvern College is a coeducational independent school located on a 250 acre campus near the town centre of Malvern, Worcestershire in England. Founded on 25 January 1865, until 1992, the College was a secondary school for boys aged 13 to 18...

. Then, following in the footsteps of George Mallory

George Mallory

George Herbert Leigh Mallory was an English mountaineer who took part in the first three British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s....

, he returned as a master to his own old school, Charterhouse, where he remained for ten years. On 12 August 1950, between Malvern and Charterhouse, he married Rosemary Campbell Davies, and they had two sons, Michael and Jeremy.

Early climbing

John Menlove Edwards

John Menlove Edwards was one of the leading British rock climbers of the interwar period and wrote poetry based on his experiences climbing....

of Liverpool. Before World War II, he helped Edwards to produce rock climbing guides to the crags of Tryfan

Tryfan

Tryfan is a mountain in Snowdonia, Wales, forming part of the Glyderau group. It is one of the most recognisable peaks in the region, having a classic pointed shape with rugged crags. At 3,010 feet above sea level it is the fifteenth highest mountain in Wales...

and Lliwedd

Y Lliwedd

Y Lliwedd is a mountain, connected to Yr Wyddfa in the Snowdonia National Park, North Wales.Its summit lies 2,946 ft above sea level....

in Snowdonia

Snowdonia

Snowdonia is a region in north Wales and a national park of in area. It was the first to be designated of the three National Parks in Wales, in 1951.-Name and extent:...

. Like other leading British climbers of the pre-World War II period, such as Mallory, Jack Longland

Jack Longland

Sir John Laurence "Jack" Longland was an educator, mountain climber, and broadcaster.He was educated at the King's School, Worcester, and Jesus College, Cambridge. He lectured in English at Durham University from 1930 to 1936. He then served as Director of Education for Derbyshire for 23 years,...

, Ivan Waller and A. B. Hargreaves, Noyce became a protégé of Geoffrey Winthrop Young

Geoffrey Winthrop Young

Geoffrey Winthrop Young D.Litt. was a British climber, poet and educator, and author of several notable books on mountaineering.-Mountaineering:...

, attending his parties at Pen-y-Pass

Pen-y-Pass

Pen-y-Pass is a mountain pass in Snowdonia, Gwynedd, north-west Wales. It is a popular location from which to walk up Snowdon, as three of the popular routes can be started here...

.

In the late 1930s, Noyce was one of a small band of Britons climbing at high standards in the Alps

Alps

The Alps is one of the great mountain range systems of Europe, stretching from Austria and Slovenia in the east through Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Germany to France in the west....

. He was well known for his speed and stamina, and in two early alpine seasons, 1937 and 1938, climbing with Armand Charlet or Hans Brantschen as his guide

Mountain guide

Mountain guides are specially trained and experienced mountaineers and professionals who are generally certified by an association. They are considered experts in mountaineering.-Skills:Their skills usually include climbing, skiing and hiking...

, he made major climbs in very fast times. In 1942, in North Wales, he achieved a non-stop solo climb of 1,370 metres. During this period Noyce wrote that he suffered three serious accidents:

The first fall refers to an incident when he was held on the rope by Edwards after falling, despite damage to the rope.

Background and approach

Noyce was a climbing member of the 1953 British Expedition to Mount Everest that made the first ascent of the mountain. According to the expedition's leader John Hunt, in the section of his The Ascent of Everest in which he outlined the qualities of his team members:Edmund Hillary

Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Percival Hillary, KG, ONZ, KBE , was a New Zealand mountaineer, explorer and philanthropist. On 29 May 1953 at the age of 33, he and Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers known to have reached the summit of Mount Everest – see Timeline of climbing Mount Everest...

, meeting Noyce for the first time as the expedition assembled in Nepal

Nepal

Nepal , officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked sovereign state located in South Asia. It is located in the Himalayas and bordered to the north by the People's Republic of China, and to the south, east, and west by the Republic of India...

, echoed Hunt's praise: "Wilf Noyce was a tough and experienced mountaineer with an impressive record of difficult and dangerous climbs. In many respects I considered Noyce the most competent British climber I had met."

At the initial meeting of the Everest team at the premises of the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

on 17 November 1952, Noyce was designated as being charge of writing (meaning the dispatches that were to be sent home from the mountain) and "volunteered to help with the packing" (he aided Stuart Bain with this). On the walk-in to the mountain, Noyce, together with Charles Evans, who had been designated as in charge of stores at the RGS meeting, were designated as the "baggage party", in charge of the clothing and equipment for the approach. Noyce was also in charge of mountaineering equipment on the ascent itself, having been instructed in the repair of high-altitude boots ("I had worked for three days with Robert Lawrie

Robert Lawrie

Robert Lawrie was a British alpine and polar equipment specialist and racing driver.Robert Lawrie was born in Burnley. He trained as a shoe and boot maker at his father's firm which he later ran. By the late 1920s he had become an accomplished climber and alpinist, and he started to design,...

's bootmakers, learning chiefly how to stick on micro-cellular rubber soles and heels"). Noyce's skills in boot repair were in demand on the ascent; according to Charles Wylie, the thin Vibram

Vibram

Vibram S.p.A. is an Italian company based in Albizzate that both manufactures and licenses the production of Vibram-branded rubber outsoles for footwear. The company is named after its founder, Vitale Bramani. Bramani is credited with inventing the first rubber lug soles for shoes...

soles that were used on the boots often peeled off at the toes but Noyce "saved the situation with some really professional repair work".

Together with George Lowe

George Lowe (mountaineer)

Wallace George Lowe, CNZM, OBE , known as George Lowe, is a New Zealand-born mountaineer, explorer, film director and educator...

, on 17 May Noyce established Camp VII on the Lhotse

Lhotse

Lhotse is the fourth highest mountain on Earth and is connected to Everest via the South Col. In addition to the main summit at 8,516 metres above sea level, Lhotse Middle is and Lhotse Shar is...

face of Everest. On 20 May he radioed to Hunt that many of the oxygen bottles (the training or Utility model, not the type that were to be used on the summit attempt) that had been ferried up to Camp VII were leaking. Hunt noted "Wilfrid, though gifted in more ways than one, has not a marked mechanical bent and we hoped his tests were not conclusive. Tom

Tom Bourdillon

Thomas Duncan Bourdillon, known as Tom Bourdillon , was an English mountaineer, a member of the team which made the first ascent of Mount Everest in 1953....

, however, had a luring fear that these very tests, carried out by a possibly anoxic

Hypoxia (medical)

Hypoxia, or hypoxiation, is a pathological condition in which the body as a whole or a region of the body is deprived of adequate oxygen supply. Variations in arterial oxygen concentrations can be part of the normal physiology, for example, during strenuous physical exercise...

Wilfrid, might have resulted in the discharging of all nine cylinders".

South Col

On 21 May Noyce and the SherpaSherpa people

The Sherpa are an ethnic group from the most mountainous region of Nepal, high in the Himalayas. Sherpas migrated from the Kham region in eastern Tibet to Nepal within the last 300–400 years.The initial mountainous migration from Tibet was a search for beyul...

Annullu (the younger brother of Da Tensing) were the first members of the expedition to reach Everest's South Col

South Col

The South Col usually refers to the southern col between Mount Everest and Lhotse, the first and fourth highest mountains in the world. When climbers attempt to climb Everest from the southeast ridge in Nepal, their final camp is situated on the South Col...

, after what Noyce said was "one of the most enjoyable days' mountaineering I've ever had". They left Camp VII at 9.30 am, both using oxygen; according to Noyce, "I had told Anullu that we would not start too early, for fear of frostbite

Frostbite

Frostbite is the medical condition where localized damage is caused to skin and other tissues due to extreme cold. Frostbite is most likely to happen in body parts farthest from the heart and those with large exposed areas...

." Several hours later they reached the highest point attained by the British expedition to date: "an aluminium piton with a great coil of thick rope" left by George Lowe and party. The climbers in the camps below, according to Hunt, were watching their progress on this vital part of the climb; by early afternoon "their speed had noticeably increased and our excitement soon grew to amazement when it dawned on us that Noyce and Annullu were heading for the South Col itself".

Not long after Hunt made that observation, they reached the Col.

In a passage in South Col, Noyce's book of the expedition published the following year, he gives an account of the scene that greeted him at the Col:

From the remains of the Swiss expedition

1952 Swiss Mount Everest Expedition

Led by Edouard Wyss-Dunant, the 1952 Swiss Mount Everest Expedition saw Raymond Lambert and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay reach a height of about on the southeast ridge, setting a new climbing altitude record, opening up a new route to Mount Everest and the paving way for further successes by other...

Noyce "picked up some Vita-Weat, a tin of sardines and a box of matches, all in perfect condition after lying exposed to the elements for over six months". Noyce and Annullu fixed a 500-ft length of nylon rope to protect the steep slopes leading up to the Col where Camp VIII was to be established ("this was to be a moral lifeline for weary Sherpas returning from the long carry"), and then descended to Camp VII which they reached at 5.30 pm. From a mountaineering perspective, as Everest veteran Chris Bonington

Chris Bonington

Sir Christian John Storey Bonington, CVO, CBE, DL is a British mountaineer.His career has included nineteen expeditions to the Himalayas, including four to Mount Everest and the first ascent of the south face of Annapurna.-Early life and expeditions:Educated at University College School in...

wrote, "[Noyce] had fulfilled his role in John Hunt's master plan, had established one vital stepping-stone for others to achieve the final goal."

According to Hunt, the climbing team had been in low spirits before Noyce and Annullu reached the South Col, but the effect of their safe return from the Col to Camp VII "had a profound impression on the waiting men. If these two could do it, so could they [...] Morale rose suddenly, inspired by fine example".

Noyce climbed up to the South Col a second time during the ascent; on 29 May, the day of the successful first ascent, he set out with three Sherpas from Camp VII, reaching the Col with one of them, Pasang Phutar, later that day; they "had each carried a double load—at least 50 lb.—from the point where the two other Sherpas had given up". Hunt noted that "Noyce and Wylie were the only two members of the climbing party to reach the South Col without oxygen."

Pasang, George Lowe and Noyce met the successful summit team of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay

Tenzing Norgay

Padma Bhushan, Supradipta-Manyabara-Nepal-Tara Tenzing Norgay, GM born Namgyal Wangdi and often referred to as Sherpa Tenzing, was a Nepalese Sherpa mountaineer...

at the Col, giving the tired climbers drinks and congratulations. It was here, 200 metres above the camp, that Hillary told Lowe, who had gone out to greet them, "Well, we knocked the bastard off." Hillary wrote: "Wilf Noyce and Pasang Puta [sic] were also in Camp and they looked after us with patience and kindness. I felt a moment of sympathy for Wilf – he was the only one left with the strength to try for the summit; but now he wouldn't get the chance. It was another foul night with strong wind and very cold temperatures ..." Noyce descended the following day with Hillary, Tenzing, Lowe and Pasang Phutar, reaching Camp IV on 30 May.

As well as naming his book of the expedition South Col, Noyce also wrote a poem called 'South Col'.

Later years

Machapuchare

Machapuchare or Machhapuchhre Lit. "Fish Tail" in English, is a mountain in the Annapurna Himal of north central Nepal...

(6,993 m) in the Annapurna

Annapurna

Annapurna is a section of the Himalayas in north-central Nepal that includes Annapurna I, thirteen additional peaks over and 16 more over ....

Himal, reaching to within 50 m of the summit before turning back at that point out of respect for local religious beliefs. Noyce and Cox also made the first ascent – via the north-east face – of Singu Chuli

Singu Chuli

Singu Chuli is one of the trekking peaks in the Nepali Himalaya range. The peak is located just west of Ganggapurna in the Annapurna Himal. A climbing permit from the NMA costs $350 USD for a team of up to four members. The peak requires ice climbing equipment....

(Fluted Peak) (6,501 m) on 13 June 1957. On 5 August 1959 Noyce, together with C. J. Mortlock and Jack Sadler, made the first British ascent of the Welzenbach route on the north face of the Dent d'Hérens

Dent d'Hérens

The Dent d'Hérens is a mountain in the Pennine Alps, lying on the border between Italy and Switzerland. The mountain lies a few kilometres west of the Matterhorn.The Aosta hut is used for the normal route.-Naming:...

. Some days later, on 15–16 August, the same party made the first British ascent of the north-east face of the Signalkuppe

Signalkuppe

The Signalkuppe is a peak in the Pennine Alps on the border between Italy and Switzerland. It is a subpeak of Monte Rosa. The mountain is named after 'the Signal', a prominent gendarme atop the east ridge.The first ascent was made by Giovanni Gnifetti, a parish priest from Alagna Valsesia,...

, the longest and most serious route on the east face of Monte Rosa

Monte Rosa

The Monte Rosa Massif is a mountain massif located in the eastern part of the Pennine Alps. It is located between Switzerland and Italy...

.

Trivor

Trivor is one of the high peaks of the Hispar Muztagh, a subrange of the Karakoram range in the Gilgit-Baltistan of Pakistan.Its height is often given as 7,728 metres, but this elevation is not consistent with photographic evidence...

(7,577 m) in Pakistan's Hispar Muztagh

Hispar Muztagh

Hispar Muztagh is a sub-range of the Karakoram mountain range. It is located in the Gojal region of the Northern Areas of Pakistan, north of Hispar Glacier, south of Shimshal Valley, and east of the Hunza Valley. It is the second highest sub-range of the Karakoram, the highest being the Baltoro...

range in 1960 together with Jack Sadler.

Noyce died in a mountaineering accident together with the 23-year-old Scot Robin Smith

Robin Smith (climber)

Robin Smith was a British climber of the 1950s and early 1960s. He died together with Wilfrid Noyce in 1962 on a snow slope in the Pamirs, during an Anglo-Soviet expedition, at the age of 23.- Life :...

in 1962 after a successful ascent of Mount Garmo

Mount Garmo

Mount Garmo is a mountain of the Pamirs in Tajikistan, Central Asia, with a height reported to be between 6,595 metres and 6,602 metres....

(6,595 m), in the Pamirs. On the descent, one of Smith or Noyce slipped on a layer of soft snow over ice, pulling the other, and they both fell 4,000 feet.

Writings

Noyce wrote widely, penning not just books, poems and scholarly articles, but also contributing to climbing guidebooks. His Scholar Mountaineers was a study of twelve writers and thinkers who had an association with mountains; these were DanteDANTE

Delivery of Advanced Network Technology to Europe is a not-for-profit organisation that plans, builds and operates the international networks that interconnect the various national research and education networks in Europe and surrounding regions...

, Petrarch

Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca , known in English as Petrarch, was an Italian scholar, poet and one of the earliest humanists. Petrarch is often called the "Father of Humanism"...

, Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer of 18th-century Romanticism. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution as well as the overall development of modern political, sociological and educational thought.His novel Émile: or, On Education is a treatise...

, Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand de Saussure was a Swiss linguist whose ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments in linguistics in the 20th century. He is widely considered one of the fathers of 20th-century linguistics...

, Goethe, Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth was a major English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with the 1798 joint publication Lyrical Ballads....

, Keats

John Keats

John Keats was an English Romantic poet. Along with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley, he was one of the key figures in the second generation of the Romantic movement, despite the fact that his work had been in publication for only four years before his death.Although his poems were not...

, Ruskin

John Ruskin

John Ruskin was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, also an art patron, draughtsman, watercolourist, a prominent social thinker and philanthropist. He wrote on subjects ranging from geology to architecture, myth to ornithology, literature to education, and botany to political...

, Leslie Stephen

Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen, KCB was an English author, critic and mountaineer, and the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.-Life:...

, Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, composer and classical philologist...

, Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI , born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was Pope from 6 February 1922, and sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929 until his death on 10 February 1939...

and Robert Falcon Scott

Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, CVO was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, 1901–04, and the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13...

. In the introduction Noyce says that he chose these figures because:

Commemoration

The "Wilfrid Noyce Community Centre" in GodalmingGodalming

Godalming is a town and civil parish in the Waverley district of the county of Surrey, England, south of Guildford. It is built on the banks of the River Wey and is a prosperous part of the London commuter belt. Godalming shares a three-way twinning arrangement with the towns of Joigny in France...

, Surrey

Surrey

Surrey is a county in the South East of England and is one of the Home Counties. The county borders Greater London, Kent, East Sussex, West Sussex, Hampshire and Berkshire. The historic county town is Guildford. Surrey County Council sits at Kingston upon Thames, although this has been part of...

– where Charterhouse

Charterhouse School

Charterhouse School, originally The Hospital of King James and Thomas Sutton in Charterhouse, or more simply Charterhouse or House, is an English collegiate independent boarding school situated at Godalming in Surrey.Founded by Thomas Sutton in London in 1611 on the site of the old Carthusian...

is located – is named after him.