Valley Campaign

Encyclopedia

|

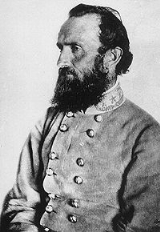

Jackson's Valley Campaign was Confederate

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army was the army of the Confederate States of America while the Confederacy existed during the American Civil War. On February 8, 1861, delegates from the seven Deep South states which had already declared their secession from the United States of America adopted the...

Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's

Stonewall Jackson

ຄຽשת״ׇׂׂׂׂ֣|birth_place= Clarksburg, Virginia |death_place=Guinea Station, Virginia|placeofburial=Stonewall Jackson Memorial CemeteryLexington, Virginia|placeofburial_label= Place of burial|image=...

famous spring 1862 campaign through the Shenandoah Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

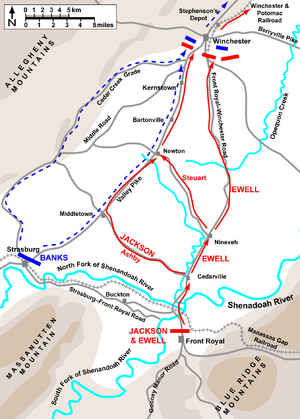

. Employing audacity and rapid, unpredictable movements on interior lines, Jackson's 17,000 men marched 646 miles (1,040 km) in 48 days and won several minor battles as they successfully engaged three Union armies

Union Army

The Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

(52,000 men), preventing them from reinforcing the Union

Union (American Civil War)

During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

offensive against Richmond

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

.

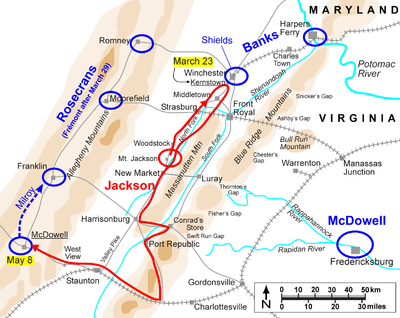

Jackson suffered a defeat (his sole defeat of the war) at the First Battle of Kernstown (March 23, 1862) against Col.

Colonel (United States)

In the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, colonel is a senior field grade military officer rank just above the rank of lieutenant colonel and just below the rank of brigadier general...

Nathan Kimball

Nathan Kimball

Nathan Kimball was a physician, politician, postmaster, and military officer, serving as a general in the Union army during the American Civil War...

(part of Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks's army), but it proved to be a strategic Confederate victory because President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

reinforced his Valley forces with troops that had originally been designated for the Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

against Richmond. On May 8, after more than a month of skirmishing with Banks, Jackson moved deceptively to the west of the Valley and drove back elements of Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont

John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont , was an American military officer, explorer, and the first candidate of the anti-slavery Republican Party for the office of President of the United States. During the 1840s, that era's penny press accorded Frémont the sobriquet The Pathfinder...

's army in the Battle of McDowell

Battle of McDowell

The Battle of McDowell, also known as Sitlington's Hill, was fought May 8, 1862, in Highland County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War...

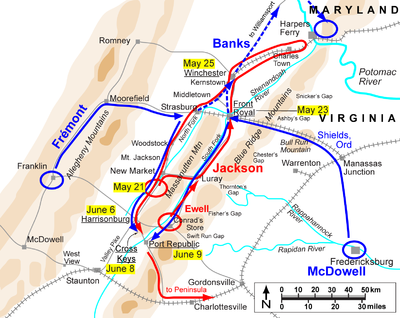

, preventing a potential combination of the two Union armies against him. Jackson then headed down the Valley once again to confront Banks. Concealing his movement in the Luray Valley

Page Valley

The Page Valley is a small valley geographically and culturally associated with the Shenandoah Valley. The valley is located between the Massanutten and Blue Ridge mountain ranges in western Virginia.-Geography:The valley is approximately long...

, Jackson joined forces with Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E...

and captured the Federal garrison at Front Royal

Battle of Front Royal

The Battle of Front Royal, also known as Guard Hill or Cedarville, was fought May 23, 1862, in Warren County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War...

on May 23, causing Banks to retreat to the north. On May 25, in the First Battle of Winchester

First Battle of Winchester

The First Battle of Winchester, fought on May 25, 1862, in and around Frederick County, Virginia, and Winchester, Virginia, was a major victory in Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War. Jackson enveloped the...

, Jackson defeated Banks and pursued him until the Union Army crossed the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

into Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

.

Bringing in Union reinforcements from eastern Virginia, Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general (United States)

A brigadier general in the United States Army, Air Force, and Marine Corps, is a one-star general officer, with the pay grade of O-7. Brigadier general ranks above a colonel and below major general. Brigadier general is equivalent to the rank of rear admiral in the other uniformed...

James Shields

James Shields

James Shields was an American politician and United States Army officer who was born in Altmore, County Tyrone, Ireland. Shields, a Democrat, is the only person in United States history to serve as a U.S. Senator for three different states...

recaptured Front Royal and planned to link up with Frémont in Strasburg

Strasburg, Virginia

Strasburg is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States, which was founded in 1761 by Peter Stover. It is the largest town, population-wise, in the county and is known for its pottery, antiques, and Civil War history...

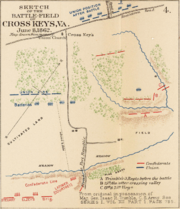

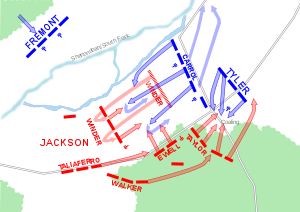

. Jackson was now threatened by three small Union armies. Withdrawing up the Valley from Winchester, Jackson was pursued by Frémont and Shields. On June 8, Ewell defeated Frémont in the Battle of Cross Keys

Battle of Cross Keys

The Battle of Cross Keys was fought on June 8, 1862, in Rockingham County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War...

and on the following day, crossed the North River to join forces with Jackson to defeat Shields in the Battle of Port Republic

Battle of Port Republic

-References:* Cozzens, Peter. Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4....

, bringing the campaign to a close.

Jackson followed up his successful campaign by forced marches to join Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

for the Seven Days Battles

Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles was a series of six major battles over the seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, away from...

outside Richmond. His audacious campaign elevated him to the position of the most famous general in the Confederacy (until this reputation was later supplanted by Lee) and has been studied ever since by military organizations around the world.

Background

In the spring of 1862 "Southern morale... was at its nadir" and "prospects for the Confederacy's survival seemed bleak." Following the successful summer of 1861, particularly the First Battle of Bull RunFirst Battle of Bull Run

First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas , was fought on July 21, 1861, in Prince William County, Virginia, near the City of Manassas...

(First Manassas), its prospects declined quickly. Union armies in the Western Theater

Western Theater of the American Civil War

This article presents an overview of major military and naval operations in the Western Theater of the American Civil War.-Theater of operations:...

, under Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

and others, captured Southern

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

territory and won significant battles at Fort Donelson

Battle of Fort Donelson

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11 to February 16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The capture of the fort by Union forces opened the Cumberland River as an avenue for the invasion of the South. The success elevated Brig. Gen. Ulysses S...

and Shiloh

Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, fought April 6–7, 1862, in southwestern Tennessee. A Union army under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had moved via the Tennessee River deep into Tennessee and...

. And in the East

Eastern United States

The Eastern United States, the American East, or simply the East is traditionally defined as the states east of the Mississippi River. The first two tiers of states west of the Mississippi have traditionally been considered part of the West, but can be included in the East today; usually in...

, Maj. Gen.

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

George B. McClellan's

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

massive Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

was approaching Richmond from the southeast in the Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

, Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War.-Early life:...

's large corps was poised to hit Richmond from the north, and Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks's army was threatening the Shenandoah Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

. However, Jackson's Confederate troops were in "excellent spirits," laying the foundation for his performance in the Valley that spring, which helped derail the Union plans and re-energize Confederate morale elsewhere.

During the Civil War, the Shenandoah Valley was one of the most strategic geographic features of Virginia. The watershed of the Shenandoah River

Shenandoah River

The Shenandoah River is a tributary of the Potomac River, long with two forks approximately long each, in the U.S. states of Virginia and West Virginia...

passed between the Blue Ridge Mountains

Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. This province consists of northern and southern physiographic regions, which divide near the Roanoke River gap. The mountain range is located in the eastern United States, starting at its southern-most...

on the east and the Allegheny Mountains

Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range , also spelled Alleghany, Allegany and, informally, the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the eastern United States and Canada...

to the west, extending 140 miles southwest from the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

at Shepherdstown

Shepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown is a town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, United States, located along the Potomac River. It is the oldest town in the state, having been chartered in 1762 by Colonial Virginia's General Assembly. Since 1863, Shepherdstown has been in West Virginia, and is the oldest town in...

and Harpers Ferry, at an average width of 25 miles. By the conventions of local residents, the "upper Valley" referred to the southwestern end, which had a generally higher elevation than the lower Valley to the northeast. Moving "up the Valley" meant traveling southwest, for instance. Between the North and South Forks of the Shenandoah River, Massanutten Mountain

Massanutten Mountain

Massanutten Mountain is a synclinal ridge in the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, located in the U.S. state of Virginia.-Geography:The mountain bisects the Shenandoah Valley just east of Strasburg in Shenandoah County in the north, to its highest peak east of Harrisonburg in Rockingham County in the...

soared 2,900 feet and separated the Valley into two halves for about 50 miles, from Strasburg

Strasburg, Virginia

Strasburg is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States, which was founded in 1761 by Peter Stover. It is the largest town, population-wise, in the county and is known for its pottery, antiques, and Civil War history...

to Harrisonburg

Harrisonburg, Virginia

Harrisonburg is an independent city in the Shenandoah Valley region of Virginia in the United States. Its population as of 2010 is 48,914, and at the 2000 census, 40,468. Harrisonburg is the county seat of Rockingham County and the core city of the Harrisonburg, Virginia Metropolitan Statistical...

. During the 19th century, there was but a single road that crossed over the mountain, from New Market

New Market, Virginia

New Market is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States. It had a population of 2,146 at the 2010 census. New Market is home to the Rebels of the Valley Baseball League, and the New Market Shockers of the Rockingham County Baseball League.-History:...

to Luray. The Valley offered two strategic advantages to the Confederates. First, a Northern army invading Virginia could be subjected to Confederate flanking attacks pouring through the many wind gaps across the Blue Ridge. Second, the Valley offered a protected avenue that allowed Confederate armies to head north into Pennsylvania unimpeded; this was the route taken by Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

to invade the North in the Gettysburg Campaign

Gettysburg Campaign

The Gettysburg Campaign was a series of battles fought in June and July 1863, during the American Civil War. After his victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia moved north for offensive operations in Maryland and Pennsylvania. The...

of 1863 and by Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early in the Valley Campaigns of 1864

Valley Campaigns of 1864

The Valley Campaigns of 1864 were American Civil War operations and battles that took place in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia from May to October 1864. Military historians divide this period into three separate campaigns, but it is useful to consider the three together and how they...

. In contrast, the orientation of the Valley offered little advantage to a Northern army headed toward Richmond. But denying the Valley to the Confederacy would be a significant blow. It was an agriculturally rich area—the 2.5 million bushels of wheat produced in 1860, for example, accounted for about 19% of the crop in the entire state and the Valley was also rich in livestock—that was used to provision Virginia's armies and the Confederate capital of Richmond. If the Federals could reach Staunton

Staunton, Virginia

Staunton is an independent city within the confines of Augusta County in the commonwealth of Virginia. The population was 23,746 as of 2010. It is the county seat of Augusta County....

in the upper Valley, they would threaten the vital Virginia and Tennessee Railroad

Virginia and Tennessee Railroad

The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad was an historic railroad in the Southern United States, much of which is incorporated into the modern Norfolk Southern Railway...

, which ran from Richmond to the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

. Stonewall Jackson wrote to a staff member, "If this Valley is lost, Virginia is lost." In addition to Jackson's campaign in 1862, the Valley was subjected to conflict for virtually the entire war, most notably in the Valley Campaigns of 1864

Valley Campaigns of 1864

The Valley Campaigns of 1864 were American Civil War operations and battles that took place in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia from May to October 1864. Military historians divide this period into three separate campaigns, but it is useful to consider the three together and how they...

.

Opposing forces

| Key subordinates of Stonewall Jackson |

|---|

| Key Union commanders |

Confederate

Stonewall Jackson's command, the Valley District of the Department of Northern Virginia, expanded significantly during the campaign as reinforcements were added, starting with a force of a mere 5,000 effectives and reaching an eventual peak of 17,000 men. It remained, however, greatly outnumbered by the various Union armies opposing it, which together numbered 52,000 men in June 1862.In March 1862, at the time of the Battle of Kernstown, Jackson commanded the brigades of Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett

Richard B. Garnett

Richard Brooke Garnett was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was killed during Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg.-Early life:...

, Col. Jesse S. Burks, Col. Samuel V. Fulkerson, and cavalry under Col. Turner Ashby

Turner Ashby

Turner Ashby, Jr. was a Confederate cavalry commander in the American Civil War. He had achieved prominence as Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's cavalry commander, in the grade of colonel, in the Shenandoah Valley before he was killed in battle in 1862...

. In early May, at the Battle of McDowell

Battle of McDowell

The Battle of McDowell, also known as Sitlington's Hill, was fought May 8, 1862, in Highland County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War...

, Jackson commanded two units that were putatively armies, although they were smaller than normal divisions

Division (military)

A division is a large military unit or formation usually consisting of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades, and in turn several divisions typically make up a corps...

: his own "Army of the Valley", consisting of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder, Col. John A. Campbell

John Allen Campbell

John Allen Campbell was a politician and officer in the U.S. Army. During the Civil War, he advanced from lieutenant to brevet brigadier general. He was appointed the first Governor of Wyoming Territory in 1869 and again in 1873...

, and Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro

William B. Taliaferro

William Booth Taliaferro , was a United States Army officer, a lawyer, legislator, and Confederate general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

; the Army of the Northwest

Confederate Army of the Northwest

The Army of the Northwest was a Confederate army early in the American Civil War.On June 8, 1861, Confederate troops operating in northwestern Virginia were designated the "Army of the Northwest" with Brig. Gen. Robert S. Garnett as commanding general. Troops of this command were engaged by Maj....

, commanded by Brig. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson

Edward Johnson (general)

Edward Johnson , also known as Allegheny Johnson , was a United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, consisted of the brigades of Cols. Zephaniah T. Conner and W.C. Scott.

In late May and June, for the battles starting at Front Royal

Battle of Front Royal

The Battle of Front Royal, also known as Guard Hill or Cedarville, was fought May 23, 1862, in Warren County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War...

, Jackson commanded two infantry divisions and a cavalry command. "Jackson's Division" consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder, Col. John A. Campbell (wounded and replaced by Col. John M. Patton, Jr.), and Col. Samuel V. Fulkerson (replaced by Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro). The Second Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E...

, consisted of the brigades commanded by Col. W.C. Scott (replaced by Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart), Brig. Gen. Arnold Elzey

Arnold Elzey

Arnold Elzey , Jr. was a soldier in both the United States Army and the Confederate Army, serving as a major general during the American Civil War...

(replaced by Col. James A. Walker

James A. Walker

James Alexander Walker was a Virginia lawyer, politician, and Confederate general during the American Civil War, later serving as a United States Congressman for two terms...

), Brig. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble

Isaac R. Trimble

Isaac Ridgeway Trimble was a United States Army officer, a civil engineer, a prominent railroad construction superintendent and executive, and a Confederate general in the American Civil War, most famous for his leadership role in the assault known as Pickett's Charge at the Battle of...

, Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor

Richard Taylor (general)

Richard Taylor was a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was the son of United States President Zachary Taylor and First Lady Margaret Taylor.-Early life:...

, and Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart (an all-Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

brigade known as the "Maryland Line"). The cavalry was commanded during the period by Col. Thomas S. Flournoy, Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart, Brig. Gen. Turner Ashby, and Col. Thomas T. Munford

Thomas T. Munford

Thomas Taylor Munford was an American farmer and Confederate brigadier general during the American Civil War.-Biography:...

.

Union

Union forces varied considerably during the campaign as armies arrived and withdrew from the Valley. The forces were generally from three independent commands, an arrangement which reduced the effectiveness of the Union response to Jackson.Initially, the Valley was the responsibility of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks. In March 1862, at the time of the Battle of Kernstown, he commanded the V Corps of the Army of the Potomac

Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the major Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War.-History:The Army of the Potomac was created in 1861, but was then only the size of a corps . Its nucleus was called the Army of Northeastern Virginia, under Brig. Gen...

; and on April 4, he assumed command of the Department of the Shenandoah. His force initially consisted of two divisions under Brig. Gens. James Shields

James Shields

James Shields was an American politician and United States Army officer who was born in Altmore, County Tyrone, Ireland. Shields, a Democrat, is the only person in United States history to serve as a U.S. Senator for three different states...

and Alpheus S. Williams

Alpheus S. Williams

Alpheus Starkey Williams was a lawyer, judge, journalist, U.S. Congressman, and a Union general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, with an independent brigade under Brig. Gen. John W. Geary

John W. Geary

John White Geary was an American lawyer, politician, Freemason, and a Union general in the American Civil War...

. At Kernstown, Shield's division was led by Col. Nathan Kimball

Nathan Kimball

Nathan Kimball was a physician, politician, postmaster, and military officer, serving as a general in the Union army during the American Civil War...

with brigades under Kimball, Col. Jeremiah C. Sullivan

Jeremiah C. Sullivan

Jeremiah Cutler Sullivan was an Indiana lawyer, antebellum United States Navy officer, and a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was among a handful of former Navy officers who later served as infantry generals during the war.-Early life and career:Jeremiah C....

, Col. Erastus B. Tyler

Erastus B. Tyler

Erastus Bernard Tyler was an American businessman, merchant, and soldier. He was a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War and fought in many of the early battles in the Eastern Theater before being assigned command of the defenses of Baltimore, Maryland. He briefly commanded the...

, and cavalry under Col. Thornton F. Brodhead. At the end of April, Shield's division would be transferred from Banks to McDowell's command, leaving Banks with just one division, under Williams, consisting of the brigades of Cols. Dudley Donnelly and George H. Gordon, and a cavalry brigade under Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch.

Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont

John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont , was an American military officer, explorer, and the first candidate of the anti-slavery Republican Party for the office of President of the United States. During the 1840s, that era's penny press accorded Frémont the sobriquet The Pathfinder...

commanded the Mountain Department, west of the Valley. In early May, part of Frémont's command consisting of Brig. Gen. Robert C. Schenck

Robert C. Schenck

Robert Cumming Schenck was a Union Army general in the American Civil War, and American diplomatic representative to Brazil and the United Kingdom. He was at both battles of Bull Run and took part in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, and the Battle of Cross Keys...

's brigade and Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy

Robert H. Milroy

Robert Huston Milroy was a lawyer, judge, and a Union Army general in the American Civil War, most noted for his defeat at the Second Battle of Winchester in 1863.-Early life:...

's brigade faced Jackson at the Battle of McDowell

Battle of McDowell

The Battle of McDowell, also known as Sitlington's Hill, was fought May 8, 1862, in Highland County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War...

. At the end of May, Fremont entered the Valley with a division under Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker

Louis Blenker

Louis Blenker was a German and American soldier.-Life in Germany:He was born at Worms, Germany. After being trained as a goldsmith by an uncle in Kreuznach, he was sent to a polytechnical school in Munich. Against his family's wishes, he enlisted in an Uhlan regiment which accompanied Otto to...

, consisting of brigades of Brig. Gen. Julius H. Stahel

Julius Stahel

Julius H. Stahel-Számwald was a Hungarian soldier who emigrated to the United States and became a Union general in the American Civil War. After the war, he served as a U.S. diplomat, a mining engineer, and a life insurance company executive...

, Col. John A. Koltes, and Brig. Gen. Henry Bohlen

Henry Bohlen

Henry Bohlen was an American Civil War Union Brigadier General. Before becoming the first foreign-born Union general in the Civil War, he fought in the Mexican-American War Henry Bohlen (October 22, 1810 – August 22, 1862) was an American Civil War Union Brigadier General. Before becoming...

, as well as brigades under Col. Gustave P. Cluseret

Gustave Paul Cluseret

Gustave Paul Cluseret was a French soldier and politician who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Biography:...

, Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy, Brig. Gen. Robert C. Schenck, and Brig. Gen. George D. Bayard.

Also at the end of May, McDowell was ordered to send troops to the Valley. Thus Shields returned to the Valley with his division consisting of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball, Brig. Gen. Orris S. Ferry

Orris S. Ferry

Orris Sanford Ferry was a Republican American lawyer and politician from Connecticut who served in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. He was also a Brigadier General in the Union Army during the American Civil War.-Early life:Ferry was born on August 15, 1823...

, Brig. Gen. Erastus B. Tyler, and Col. Samuel S. Carroll

Samuel S. Carroll

Samuel Spriggs "Red" Carroll was a career officer in the United States Army who rose to the rank of brigadier general during the American Civil War...

.

Initial movements

On November 4, 1861, Jackson accepted command of the Valley DistrictValley District

The Valley District was an organization of the Confederate States Army and subsection of the Department of Northern Virginia during the American Civil War, responsible for operations between the Blue Ridge Mountains and Allegheny Mountains of Virginia. It was created on October 22, 1861, and was...

, with his headquarters at Winchester

Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is an independent city located in the northwestern portion of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the USA. The city's population was 26,203 according to the 2010 Census...

. Jackson, recently a professor at Virginia Military Institute

Virginia Military Institute

The Virginia Military Institute , located in Lexington, Virginia, is the oldest state-supported military college and one of six senior military colleges in the United States. Unlike any other military college in the United States—and in keeping with its founding principles—all VMI students are...

and suddenly a hero at First Manassas, was familiar with the valley terrain, having lived there for many years. His command included the Stonewall Brigade

Stonewall Brigade

The Stonewall Brigade of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, was a famous combat unit in United States military history. It was trained and first led by General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, a professor from Virginia Military Institute...

and a variety of militia units. In December, Jackson was reinforced by Brig. Gen. William W. Loring

William W. Loring

William Wing Loring was a soldier from North Carolina who served in the armies of the United States, the Confederacy, and Egypt.-Early life:...

and 6,000 troops, but his combined force was insufficient for offensive operations. While Banks remained north of the Potomac River

Potomac River

The Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, located along the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. The river is approximately long, with a drainage area of about 14,700 square miles...

, Jackson's cavalry commander, Col. Turner Ashby

Turner Ashby

Turner Ashby, Jr. was a Confederate cavalry commander in the American Civil War. He had achieved prominence as Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's cavalry commander, in the grade of colonel, in the Shenandoah Valley before he was killed in battle in 1862...

, raided the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, abbreviated as the C&O Canal, and occasionally referred to as the "Grand Old Ditch," operated from 1831 until 1924 parallel to the Potomac River in Maryland from Cumberland, Maryland to Washington, D.C. The total length of the canal is about . The elevation change of...

and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was one of the oldest railroads in the United States and the first common carrier railroad. It came into being mostly because the city of Baltimore wanted to compete with the newly constructed Erie Canal and another canal being proposed by Pennsylvania, which...

. In the Romney Expedition

Romney Expedition

The Romney Expedition was a military expedition of the Confederate States Army during the early part of the American Civil War. It is named for Romney, West Virginia, which at the time was still in the state of Virginia. The expedition was conducted in this locale from January 1 to January 24,...

of early January 1862, Jackson fought inconclusively with two small Union posts at Hancock, Maryland

Battle of Hancock

The Battle of Hancock, also called the Romney Campaign, was a battle fought during the Romney Expedition, occurred January 5–6, 1862, in Washington County, Maryland, and Morgan County, West Virginia, as part of Maj. Gen. Thomas J...

, and Bath

Bath (Berkeley Springs), West Virginia

Bath is a town in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia, United States. It is the county seat of Morgan County. The town is incorporated as Bath, but it is often referred to by the name of its post office, Berkeley Springs. The population of the town was 663 according to the 2000 United States...

.

In late February, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

ordered Banks, reinforced by Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick was a teacher, a career military officer, and a Union Army general in the American Civil War. He was the highest ranking Union casualty in the Civil War, killed by a sniper at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.-Early life:Sedgwick was born in the Litchfield Hills town of...

, across the Potomac to protect the canal and railroad from Ashby. Banks moved south against Winchester in conjunction with Shields's division approaching from the direction of Romney. Jackson's command was operating as the left wing of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston was a career U.S. Army officer, serving with distinction in the Mexican-American War and Seminole Wars, and was also one of the most senior general officers in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

's army, and when Johnston withdrew from Manassas

Manassas, Virginia

The City of Manassas is an independent city surrounded by Prince William County and the independent city of Manassas Park in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Its population was 37,821 as of 2010. Manassas also surrounds the county seat for Prince William County but that county...

to Culpeper

Culpeper, Virginia

Culpeper is an incorporated town in Culpeper County, Virginia, United States. The population was 9,664 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Culpeper County. Culpeper is part of the Culpeper Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Culpeper County. Both the Town of Culpeper and...

in March, Jackson's position at Winchester was isolated. He began withdrawing "up" the Valley (to the higher elevations at the southwest end of the Valley) to cover the flank of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston was a career U.S. Army officer, serving with distinction in the Mexican-American War and Seminole Wars, and was also one of the most senior general officers in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War...

's army, withdrawing from the Centreville

Centreville, Virginia

Centreville is an unincorporated community in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. Recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau as a Census Designated Place , the community population was 71,135 as of the 2010 census and is approximately west of Washington, DC.-Colonial Period:Beginning in the 1760s,...

–Manassas

Manassas, Virginia

The City of Manassas is an independent city surrounded by Prince William County and the independent city of Manassas Park in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Its population was 37,821 as of 2010. Manassas also surrounds the county seat for Prince William County but that county...

area to protect Richmond. Without this protective movement, the Federal army under Banks might strike at Johnston through passes in the Blue Ridge Mountains. By March 12, 1862, Banks occupied Winchester

Winchester, Virginia

Winchester is an independent city located in the northwestern portion of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the USA. The city's population was 26,203 according to the 2010 Census...

just after Jackson had withdrawn from the town, marching at a leisurely pace 42 miles up the Valley Pike

Valley Pike

Valley Pike or Valley Turnpike is the traditional name given for the Indian trail and roadway which now is designated as U.S. Highway 11 in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia....

to Mount Jackson

Mount Jackson, Virginia

Mount Jackson is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,994 at the 2010 census.-Geography:Mount Jackson is located at in the southern part of Shenandoah County, Virginia at...

. On March 21, Jackson received word that Banks was splitting his force, with two divisions (under Brig. Gens. John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick

John Sedgwick was a teacher, a career military officer, and a Union Army general in the American Civil War. He was the highest ranking Union casualty in the Civil War, killed by a sniper at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.-Early life:Sedgwick was born in the Litchfield Hills town of...

and Alpheus S. Williams

Alpheus S. Williams

Alpheus Starkey Williams was a lawyer, judge, journalist, U.S. Congressman, and a Union general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

) returning to the immediate vicinity of Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, freeing up other Union troops to participate in Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

's Peninsula Campaign against Richmond. The remaining division, under Brig. Gen. James Shields

James Shields

James Shields was an American politician and United States Army officer who was born in Altmore, County Tyrone, Ireland. Shields, a Democrat, is the only person in United States history to serve as a U.S. Senator for three different states...

, was stationed at Strasburg

Strasburg, Virginia

Strasburg is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States, which was founded in 1761 by Peter Stover. It is the largest town, population-wise, in the county and is known for its pottery, antiques, and Civil War history...

to guard the lower (northeastern) Valley, and intelligence indicated that it was withdrawing toward Winchester. Banks made preparations to leave the Valley personally on March 23.

Valley Campaign

Kernstown (March 23, 1862)

Jackson's orders from Johnston were to prevent Banks's force from leaving the Valley, which it appeared they were now doing. Jackson turned his men around and, in one of the more grueling forced marches of the war, moved northeast 25 miles on March 22 and another 15 to Kernstown on the morning of March 23. Ashby's cavalry skirmished with the Federals on March 22, during which engagement Shields was wounded with a broken arm from an artillery shell fragment. Despite his injury, Shields sent part of his division south of Winchester and one brigade marching to the north, seemingly abandoning the area, but in fact halting nearby to remain in reserve. He then turned over tactical command of his division to Col. Nathan Kimball, although throughout the battle to come, he sent numerous messages and orders to Kimball. Confederate loyalists in Winchester mistakenly informed Turner Ashby that Shields had left only four regiments and a few guns (about 3,000 men) and that these remaining troops had orders to march for Harpers Ferry in the morning. Jackson marched aggressively north with his 3,000-man division, reduced from its peak as stragglers fell out of the column, unaware that he was soon to be attacking almost 9,000 men.Jackson moved north from Woodstock

Woodstock, Virginia

Woodstock is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States. It has a population of 5,097 according to the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Shenandoah County....

and arrived before the Union position at Kernstown around 11 a.m., Sunday, March 23. He sent Turner Ashby on a feint

Feint

Feint is a French term that entered English from the discipline of fencing. Feints are maneuvers designed to distract or mislead, done by giving the impression that a certain maneuver will take place, while in fact another, or even none, will...

against Kimball's position on the Valley Turnpike while his main force—the brigades of Col. Samuel Fulkerson and Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett

Richard B. Garnett

Richard Brooke Garnett was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was killed during Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg.-Early life:...

(the Stonewall Brigade

Stonewall Brigade

The Stonewall Brigade of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, was a famous combat unit in United States military history. It was trained and first led by General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, a professor from Virginia Military Institute...

)—attacked the Union artillery position on Pritchard Hill. The lead brigade under Fulkerson was repulsed, so Jackson decided to move around the Union right flank, about 2 miles west on Sandy Ridge, which appeared to be unoccupied. Kimball countered the maneuver by moving his brigade under Col. Erastus B. Tyler

Erastus B. Tyler

Erastus Bernard Tyler was an American businessman, merchant, and soldier. He was a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War and fought in many of the early battles in the Eastern Theater before being assigned command of the defenses of Baltimore, Maryland. He briefly commanded the...

to the west, but Fulkerson's men reached a stone wall facing a clearing on the ridge before the Union men could.

Around 4 p.m, Tyler attacked Fulkerson and Garnett on a narrow front. The Confederates were temporarily able to counter this attack with their inferior numbers by firing fierce volleys from behind the stone wall. Jackson, finally realizing the strength of the force opposing him, rushed reinforcements to his left, but by the time they arrived around 6 p.m., Garnett's Stonewall Brigade had run out of ammunition and he pulled them back, leaving Fulkerson's right flank exposed. Jackson tried in vain to rally his troops to hold, but the entire Confederate force was forced into a general retreat. Kimball organized no effective pursuit.

Union casualties were 590 (118 killed, 450 wounded, 22 captured or missing), Confederate 718 (80 killed, 375 wounded, 263 captured or missing). Despite the Union victory, President Lincoln was disturbed by Jackson's audacity and his potential threat to Washington. He sent Banks back to the Valley along with Alpheus Williams's division. He also was concerned that Jackson might move into western Virginia against Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont

John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont , was an American military officer, explorer, and the first candidate of the anti-slavery Republican Party for the office of President of the United States. During the 1840s, that era's penny press accorded Frémont the sobriquet The Pathfinder...

, so he ordered that the division of Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker

Louis Blenker

Louis Blenker was a German and American soldier.-Life in Germany:He was born at Worms, Germany. After being trained as a goldsmith by an uncle in Kreuznach, he was sent to a polytechnical school in Munich. Against his family's wishes, he enlisted in an Uhlan regiment which accompanied Otto to...

be detached from McClellan's Army of the Potomac and sent to reinforce Frémont. Lincoln also took this opportunity to re-examine Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan was a major general during the American Civil War. He organized the famous Army of the Potomac and served briefly as the general-in-chief of the Union Army. Early in the war, McClellan played an important role in raising a well-trained and organized army for the Union...

's plans for the defenses of Washington while the Peninsula Campaign was underway and decided that the forces were insufficient. He eventually ordered that the corps of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, which was moving south against Richmond in support of McClellan, remain in the vicinity of the capital. McClellan claimed that the loss of these forces prevented him from taking Richmond during his campaign. The strategic realignment of Union forces caused by Jackson's battle at Kernstown—the only battle he lost in his military career—turned out to be a strategic victory for the Confederacy.

After the battle, Jackson arrested Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett

Richard B. Garnett

Richard Brooke Garnett was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was killed during Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg.-Early life:...

for retreating from the battlefield before permission was received. He was replaced by Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder

Charles Sidney Winder

Charles Sidney Winder , was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general officer in the American Civil War. He was killed in action during the Battle of Cedar Mountain.-Early life and career:...

. Garnett suffered from the humiliation of his court-martial for over a year, until he was finally killed in Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee against Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's Union positions on Cemetery Ridge on July 3, 1863, the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Its futility was predicted by the charge's commander,...

at the Battle of Gettysburg

Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg , was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The battle with the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War, it is often described as the war's turning point. Union Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade's Army of the Potomac...

.

Retreating from the Valley (March 24 – May 7)

At first light the day after Kernstown, Union forces pursued Jackson and drove Ashby's cavalry in a panic. However, Banks called off the pursuit while supply problems were addressed. For the next three days the Union forces advanced slowly while Jackson retreated to Mount Jackson. It was there that he directed Capt. Jedediah HotchkissJedediah Hotchkiss

Jedediah Hotchkiss , also known as Jed, was an educator and the most famous cartographer and topographer of the American Civil War...

, "I want you to make me a map of the Valley, from Harpers Ferry to Lexington

Lexington, Virginia

Lexington is an independent city within the confines of Rockbridge County in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The population was 7,042 in 2010. Lexington is about 55 minutes east of the West Virginia border and is about 50 miles north of Roanoke, Virginia. It was first settled in 1777.It is home to...

, showing all the points of offense and defense." Given Hotchkiss's mapmaking skills, Jackson would have a significant advantage over his Federal opponents in the campaign to come. On April 1, Banks lunged forward, advancing to Woodstock along Stony Creek, where he once again was delayed by supply problems. Jackson took up a new position at Rude's Hill near Mount Jackson and New Market

New Market, Virginia

New Market is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States. It had a population of 2,146 at the 2010 census. New Market is home to the Rebels of the Valley Baseball League, and the New Market Shockers of the Rockingham County Baseball League.-History:...

.

Banks advanced again on April 16, surprising Ashby's cavalry by fording Stony Creek at a place they had neglected to picket, capturing 60 of the horsemen, while the remainder of Ashby's command fought their way back to Jackson's position on Rude's Hill. Jackson assumed that Banks had been reinforced, so he abandoned his position and marched quickly up the Valley to Harrisonburg

Harrisonburg, Virginia

Harrisonburg is an independent city in the Shenandoah Valley region of Virginia in the United States. Its population as of 2010 is 48,914, and at the 2000 census, 40,468. Harrisonburg is the county seat of Rockingham County and the core city of the Harrisonburg, Virginia Metropolitan Statistical...

on April 18. On April 19, his men marched 20 miles east out of the Shenandoah valley to Swift Run Gap

Swift Run Gap

Swift Run Gap is a wind gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains located in the U.S. state of Virginia.-Geography:At an elevation of , it is the site of the mountain crossing of U.S...

. Banks occupied New Market and crossed Massanutten Mountain to seize the bridges across the South Fork in the Luray Valley, once again besting Ashby's cavalry, who failed to destroy the bridges in time. Banks now controlled the valley as far south as Harrisonburg.

Though Banks was aware of Jackson's location, he misinterpreted Jackson's intent, thinking that Jackson was heading east of the Blue Ridge to aid Richmond. Without clear direction from Washington as to his next objective, Banks proposed his force also be sent east of the Blue Ridge, telling his superiors that "such order would electrify our force." Instead, Lincoln decided to detach Shield's division and transfer it Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War.-Early life:...

at Fredericksburg

Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia located south of Washington, D.C., and north of Richmond. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 24,286...

, leaving Banks in the Valley with only a single division. Banks was then instructed to retreat up the valley and assume a defensive position at Strasburg.

By this time, McClellan's Peninsula Campaign

Peninsula Campaign

The Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B...

was well underway and Joseph E. Johnston had relocated most of his army for the direct protection of Richmond, leaving Jackson's force isolated. Johnston sent new orders to Jackson, instructing him to prevent Banks from seizing Staunton and the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, reinforcing him with the 8,500-man division under Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

Richard S. Ewell

Richard Stoddert Ewell was a career United States Army officer and a Confederate general during the American Civil War. He achieved fame as a senior commander under Stonewall Jackson and Robert E...

, left behind at Brandy Station

Brandy Station, Virginia

Brandy Station is an unincorporated community in Culpeper County, Virginia, United States. Its original name was Brandy. The name Brandy Station comes from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad station that was constructed in the 19th century....

. Jackson, at a strong defensive position on Rude's Hill, corresponded with Ewell to develop a strategy for the campaign.

During this period, Jackson also faced difficulty within his own command. He arrested Garnett and had a nasty confrontation with Turner Ashby in which Jackson displayed his displeasure at Ashby's performance by stripping him of 10 of his 21 cavalry companies and reassigning them to Charles S. Winder, Garnett's replacement in command of the Stonewall Brigade. Winder mediated between the two officers and the stubborn Jackson uncharacteristically backed down, restoring Ashby's command. More importantly, Jackson received an April 21 letter from Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War....

, military adviser to President

President of the Confederate States of America

The President of the Confederate States of America was the Head of State and Head of Government of the Confederate States of America, which was formed from the states which declared their secession from the United States, thus precipitating the American Civil War. The only person to hold the...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Finis Davis , also known as Jeff Davis, was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the American Civil War, serving as President for its entire history. He was born in Kentucky to Samuel and Jane Davis...

, requesting that he and Ewell attack Banks to reduce the threat against Richmond that was being posed by McDowell at Fredericksburg.

Jackson's plan was to have Ewell's division move into position at Swift Run Gap to threaten Banks's flank, while Jackson's force marched toward the Allegheny Mountains to assist the detached 2,800 men under Brig. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson

Edward Johnson (general)

Edward Johnson , also known as Allegheny Johnson , was a United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War.-Early life:...

, who were resisting the advance toward Staunton of Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy, the leading element of Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont's army. If Frémont and Banks were allowed to combine, Jackson's forces could be overwhelmed, so Jackson planned to defeat them in detail. Without waiting for Lee's reply, Jackson executed his plan and on April 30, Ewell's division replaced Jackson's men at Swift Run Gap. Jackson marched south to the town of Port Republic in heavy rains and on May 2, turned his men east in the direction of Charlottesville

Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville is an independent city geographically surrounded by but separate from Albemarle County in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States, and named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the queen consort of King George III of the United Kingdom.The official population estimate for...

and began marching over the Blue Ridge. To the surprise of his men and officers, whom Jackson habitually left in the dark as to his intentions, on May 4 they boarded trains that were heading west, not east toward Richmond, as they had anticipated. The movement to the east had been a clever deception. On May 5, Jackson's army camped around Staunton, about 6 miles from Johnson's command. On May 7, Milroy received intelligence that Jackson and Johnson were combining against him and he began to fall back toward the Alleghenies.

McDowell (May 8)

On May 8, Jackson arrived at McDowell, a village in Highland CountyHighland County, Virginia

As of the census of 2000, there were 2,536 people, 1,131 households, and 764 families residing in the county. The population density was 6 people per square mile . There were 1,822 housing units at an average density of 4 per square mile...

, to find that Allegheny Johnson was deploying his infantry. The Union force of about 6,000 under Milroy and Schenck was camped in the village to the west side of the Bullpasture River

Bullpasture River

The Bullpasture River is a tributary of the Cowpasture River of Virginia in the United States.The Bullpasture River flows through Highland County, Virginia from its headwaters on the boundary between Virginia and West Virginia...

. Overlooking the scene was a spur of Bullpasture Mountain known as Sitlington Hill, a mile-long plateau that could potentially dominate the Union position. However, there were two disadvantages: the single trail that reached the summit was so difficult that artillery could not be deployed there, and the rugged terrain—densely forested, steep slopes and ravines—offered opportunities for Union attackers to climb the 500 feet to the summit without being subjected to constant Confederate fire.

The Union generals realized that they were outnumbered by the 10,000 men that Jackson and Johnson commanded and that their men would be particularly vulnerable to artillery fire from Sitlington Hill. They did not realize that Jackson could not bring up his artillery. Therefore, in order to buy time for their troops to withdraw at night, Milroy recommended a preemptive assault on the hill and Schenck, his superior officer, approved. At about 4:30 p.m., 2,300 Federal troops crossed the river and assaulted Sitlington Hill. Their initial assault almost broke Johnson's right, but Jackson sent up Taliaferro's infantry and repulsed the Federals. The next attack was at the vulnerable center of the Confederate line, where the 12th Georgia Infantry occupied a salient that was subjected to fire from both sides. The Georgians, the only non-Virginians on the Confederate side, proudly and defiantly refused to withdraw to a more defensible position and took heavy casualties as they stood and fired, silhouetted against the bright sky as easy targets at the crest of the hill. One Georgia private exclaimed, "We did not come all this way to Virginia to run before Yankees." By the end of the day the 540 Georgians suffered 180 casualties, losses three times greater than any other regiment on the field. Johnson was wounded and Taliaferro assumed command of the battle while Jackson brought up additional reinforcements. The fighting continued until about 10 p.m., when the Union troops withdrew.

Milroy and Schenck marched their men north from McDowell beginning at 12:30 a.m. on May 9. Jackson attempted to pursue, but by the time his men started the Federals were already 13 miles away. On a high ridge overlooking the road to Franklin

Franklin, West Virginia

Franklin is a town in Pendleton County, West Virginia, United States. The population was 797 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Pendleton County...

, Schenck took up a defensive position and Jackson did not attempt to attack him. Union casualties were 259 (34 killed, 220 wounded, 5 missing), Confederate 420 (116 killed, 300 wounded, 4 missing), one of the rare cases in the Civil War where the attacker lost fewer men than the defender.

Conflicting orders (May 10–22)

While Jackson was at McDowell, Ewell was fidgeting at Swift Run Gap, trying to sort out numerous orders he was receiving from Jackson and Johnston. On May 13 Jackson ordered Ewell to pursue Banks if he withdrew down the Valley from Strasburg, whereas Johnston had ordered Ewell to leave the Valley and return to the army protecting Richmond if Banks moved eastward to join McDowell at Fredericksburg. Since Shields's division was reported to have left the Valley, Ewell was in a quandary about which orders to follow. He met in person with Jackson on May 18 at Mount Solon and the two generals decided that while in the Valley, Ewell reported operationally Jackson, and that a prime opportunity existed to attack Banks's army, now depleted to fewer than 10,000 men, with their combined forces. When subsequent peremptory orders came to Ewell from Johnston to abandon this idea and march to Richmond, Jackson was forced to telegraph for help from Robert E. Lee, who convinced President Davis that a potential victory in the Valley had more immediate importance than countering Shields. Johnston modified his orders to Ewell: "The object you have to accomplish is the prevention of the junction of General Banks's troops those of General McDowell."On May 21, Jackson marched his command east from New Market

New Market, Virginia

New Market is a town in Shenandoah County, Virginia, United States. It had a population of 2,146 at the 2010 census. New Market is home to the Rebels of the Valley Baseball League, and the New Market Shockers of the Rockingham County Baseball League.-History:...

over Massanutten Mountain, combining with Ewell on May 22, and proceeded down the Luray Valley. Their speed of forced marching was typical of the campaign and earned his infantrymen the nickname of "Jackson's foot cavalry". He sent Ashby's cavalry directly north to make Banks think that he was going to attack Strasburg, where Banks began to be concerned that his 4,476 infantry, 1,600 cavalry, and 16 artillery pieces might be insufficient to withstand Jackson's 16,000 men. However, Jackson's plan was first to defeat the small Federal outpost at Front Royal (about 1,000 men of the 1st Maryland Infantry under Col. John R. Kenly

John Reese Kenly

John Reese Kenly was an American lawyer, and a Union general in the American Civil War.-Biography:...

), a turning movement

Turning movement

In military tactics, a turning movement involves an attacker's forces reaching the rear of a defender's forces, separating the defender from their principal defensive positions and placing them in a pocket...

that would make the Strasburg position untenable.

Front Royal (May 23)

Early on May 23, Turner Ashby and a detachment of cavalry forded the South Fork of the Shenandoah River and rode northwest to capture a Union depot and railroad trestle at Buckton Station. Two companies of Union infantry defended the structures briefly, but the Confederates prevailed and burned the building, tore up railroad track, and cut the telegraph wires, isolating Front Royal from Banks at Strasburg. Meanwhile, Jackson led his infantry on a detour over a path named Gooney Manor Road to skirt the reach of Federal guns on his approach to Front Royal. From a ridge south of town, Jackson observed that the Federals were camped near the confluence of the South and North Forks and that they would have to cross two bridges in order to escape from his pending attack.

The center of Jackson's line of battle was the ferocious Louisiana Tigers

Louisiana Tigers

Louisiana Tigers was the common nickname for certain infantry troops from the state of Louisiana in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Originally applied to a specific company, the nickname expanded to a battalion, then to a brigade, and eventually to all Louisiana troops...

battalion

Battalion

A battalion is a military unit of around 300–1,200 soldiers usually consisting of between two and seven companies and typically commanded by either a Lieutenant Colonel or a Colonel...

(150 men, part of Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor's

Richard Taylor (general)

Richard Taylor was a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He was the son of United States President Zachary Taylor and First Lady Margaret Taylor.-Early life:...

brigade in Ewell's division), commanded by Col. Roberdeau Wheat

Chatham Roberdeau Wheat

Chatham Roberdeau Wheat was a Captain in the United States Army Volunteers during the Mexican War, Louisiana State Representative, lawyer, mercenary in Cuba, Mexico, and Italy, adventurer, and major in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.-Early life and career:Born in...

, and the 1st Maryland Infantry, the latter bitter enemies of Kenly's Union 1st Maryland Infantry. The first shots were fired around 2 p.m. and the Confederates quickly pushed the small Federal detachment out of town. Kenly and his men made a stand on a hill just north of town and Jackson prepared to charge them with the Marylanders in the center and the Louisianians against their left flank. Before the attack could commence, Kenly saw Confederate cavalry approaching the bridges that he needed for his escape route and he immediately ordered his men to abandon their position. They first crossed the South Fork bridges and then the wooden Pike Bridge over the North Fork, which they set afire behind them. Taylor's Brigade raced in pursuit and Jackson ordered them to cross the burning bridge. As he saw the Federals escaping, Jackson was frustrated that he had no artillery to fire at them. His guns were delayed on the Gooney Manor Road detour route the infantry had taken and Ashby's cavalry had failed to deliver Jackson's orders for them to take the direct route after the battle started.

Thomas Flournoy

Thomas Stanhope Flournoy was a U.S. Representative from Virginia and a cavalry officer in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War....

of the 6th Virginia Cavalry

6th Virginia Cavalry

The 6th Virginia Volunteer Cavalry Regiment was a cavalry regiment raised in Virginia for service in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. It fought mostly with the Army of Northern Virginia....

arrived at that moment and Jackson set them off in pursuit of Kenly. The retreating Union troops were forced to halt and make a stand at Cedarville. Although the cavalrymen were outnumbered three to one, they charged the Union line, which broke but reformed. A second charge routed the Union detachment. The results of the battle were lopsided. Union casualties were 773, of which 691 were captured. Confederate losses were 36 killed and wounded. Jackson's men captured about $300,000 of Federal supplies; Banks soon became known as "Commissary Banks" to the Confederates because of the many provisions they won from him during the campaign. Banks initially resisted the advice of his staff to withdraw, assuming the events at Front Royal were merely a diversion. As he came to realize that his position had been turned, at about 3 a.m. he ordered his sick and wounded to be sent from Strasburg to Winchester and his infantry began to march midmorning on May 24.

The most significant after effect of Banks's minor loss at Front Royal was a decision by Abraham Lincoln to redirect 20,000 men from the corps of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell was a career American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War.-Early life:...

to the Valley from their intended mission to reinforce George B. McClellan on the Peninsula. At 4 p.m. on May 24, he telegraphed to McClellan, "In consequence of General Banks's critical position I have been compelled to suspend General McDowell's movements to you. The enemy are making a desperate push upon Harper's Ferry, and we are trying to throw Frémont's force and part of McDowell's in their rear."

Winchester (May 25)

Receiving word from Steuart that the Federals had indeed begun a retreat down the Valley Pike, Jackson began directing forces to Middletown. Although they had to contend with Union cavalry (five companies of the 1st Maine and two companies of the 1st Vermont) and were thus delayed en route, they reached a rise outside of Middletown at about 3 p.m. and began artillery bombardments of the Union column. The chaos that this produced was exacerbated by a charge by the Louisiana Tigers, who began looting and pillaging in the wagon train. When Union artillery and infantry arrived to challenge Jackson at around 4 p.m, Richard Taylor's infantry turned to meet the threat while Jackson sent his artillery and cavalry north to harass the Union column ahead. By the time Taylor's attack started the Union troops had withdrawn and Jackson realized that it was merely the rearguard of Banks's column. He sent word to Ewell to move quickly to Winchester and deploy for an attack south of the town. Jackson's men began a pursuit down the Valley Pike, but they were dismayed to see that Ashby's cavalrymen had paused to loot the wagon train and many of them had become drunk from Federal whiskey. The pursuit continued long after dark and after 1 a.m., Jackson reluctantly agreed to allow his exhausted men to rest for two hours.

Jackson's troops were awakened at 4 a.m. on May 25 to fight the second Sunday battle of the campaign. Jackson was pleased to find during a personal reconnaissance that Banks had not properly secured a key ridge south of the town. He ordered Charles Winder's Stonewall Brigade to occupy the hill, which they did with little opposition, but they were soon subjected to punishing artillery and small arms fire from a second ridge to the southwest—Bower's Hill, the extreme right flank of the Federal line—and their attack stalled. Jackson ordered Taylor's Brigade to deploy to the west and the Louisianians conducted a strong charge against Bower's Hill, moving up the steep slope and over a stone wall. At the same time, Ewell's men were outflanking the extreme left of the Union line. The Union lines broke and the soldiers retreated through the streets of town. Jackson later wrote that Banks's troops "preserved their organization remarkably well" through the town. They did so under unusual pressure, as numerous civilians—primarily women—fired at the men and hurled objects from doorways and windows. Jackson was overcome with enthusiasm and rode cheering after the retreating enemy. When a staff officer protested that he was in an exposed position, Jackson shouted "Go back and tell the whole army to press forward to the Potomac!"

The Confederate pursuit was ineffective because Ashby had ordered his cavalry away from the mainstream to chase a Federal detachment. Jackson lamented, "Never was there such a chance for cavalry. Oh that my cavalry was in place!" The Federals fled relatively unimpeded for 35 miles in 14 hours, crossing the Potomac River into Williamsport, Maryland

Williamsport, Maryland

Williamsport is a town in Washington County, Maryland, United States. The population was 1,868 at the 2000 census and 2,278 as of July 2008.-Geography: Williamsport is located at ....

. Union casualties were 2,019 (62 killed, 243 wounded, and 1,714 missing or captured), Confederate losses were 400 (68 killed, 329 wounded, and 3 missing).

Union armies pursue Jackson

Word of Banks's ejection from the Valley caused consternation in Washington because of the possibility that the audacious Jackson might continue marching north and threaten the capital. President Lincoln, who in the absence of a general in chief was exerting day to day strategic control over his armies in the field, took aggressive action in response. Not yielding to panic and drawing troops in for the immediate defense of the capital, he planned an elaborate offensive. He ordered Frémont to march from Franklin to Harrisonburg to engage Jackson and Ewell, to "operate against the enemy in such a way as to relieve Banks." He also sent orders to McDowell at Fredericksburg:Lincoln's plan was to spring a trap on Jackson using three armies. Frémont's movement to Harrisonburg would place him on Jackson's supply line. Banks would recross the Potomac and pursue Jackson if he moved up the Valley. The detachment from McDowell's corps would move to Front Royal and be positioned to attack and pursue Jackson's column as it passed by, and then to crush Jackson's army against Frémont's position at Harrisonburg. Unfortunately for Lincoln, his plan was complex and required synchronized movements by separate commands. McDowell was unenthusiastic about his role, wishing to retain his original mission of marching against Richmond to support McClellan, but he sent the division of Brig. Gen. James Shields, recently arrived from Banks's army, marching back to the Valley, to be followed by a second division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord

Edward Ord

Edward Otho Cresap Ord was the designer of Fort Sam Houston, and a United States Army officer who saw action in the Seminole War, the Indian Wars, and the American Civil War. He commanded an army during the final days of the Civil War, and was instrumental in forcing the surrender of Confederate...

. But Frémont was the real problem for Lincoln's plan. Rather than marching east to Harrisonburg as ordered, he took note of the exceptionally difficult road conditions on Lincoln's route and marched north to Moorefield

Moorefield, West Virginia

Moorefield is a town in Hardy County, West Virginia, USA. Moorefield is the county seat of Hardy County. It was originally chartered in 1777 and named for Conrad Moore, who owned the land upon which the town was laid out...