United States Exploring Expedition

Encyclopedia

The United States Exploring Expedition was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean

and surrounding lands conducted by the United States

from 1838 to 1842. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones

. The voyage was authorized by Congress

in 1836. It is sometimes called the "U.S. Ex. Ex." for short, or the "Wilkes Expedition" in honor of its next appointed commanding officer, United States Navy

Lieutenant

Charles Wilkes

. The expedition was of major importance to the growth of science in the United States, in particular the then-young field of oceanography

. During the event, armed conflict between Pacific islanders and the expedition was not uncommon and dozens of natives were killed in action, as well as a few Americans.

In May, 1828, the United States Congress, after prodding by President

In May, 1828, the United States Congress, after prodding by President

John Quincy Adams

, voted to send an expedition around the world with the understanding that the country would derive great benefit. It was to promote commerce and to offer protection to the heavy investment in the whaling

and seal hunting

industries, chiefly in the Pacific Ocean. Congress also agreed that a public ship or ships should be used. At the time, the only ships owned by the government capable of such a circumnavigation

were those of the navy. So, in fact, Congress had decided that a naval expedition be authorized. There were to be many unforeseen impediments and it was not until May 18, 1836, that an act was passed, which authorized funding. Even with the burden of finance lifted, there were another two years of alteration of formation and command before six oddly assorted ships moved down from Norfolk to Hampton Roads

on August 9, 1838. On August 17, after being joined by the tenders Sea Gull and Flying-Fish which delivered Lieutenant Wilkes final orders and at 15:00 hours the afternoon of August 18 the vessels weighed anchor. Due to light breezes the expedition did not discharge their pilots until 09:00 August 19 when they passed Cape Henry Light. By 11:00 the small fleet was standing to open seas.

Originally the expedition was first organized under Commodore Jones, however he subsequently resigned the station. Several more senior officers had either resigned from or indicated their unwillingness to accept command of the expedition. Command was finally vested in Lieutenant Wilkes. The three duties laid down were daunting to officers trained only in fighting ships. In addition to exploration, the naval squadron was tasked with the duties to survey both the newly found areas and survey other areas previously discovered, but about which there was insufficient knowledge. As well, a scientific corps, of all civilians, was to be included an additional command responsibility. There were few officers in the American navy at that time with any surveying experience and none with a background of working alongside scientists. The United States Coast Survey, where most of the surveyors were employed and learned their trade, was a civilian organization. Wilkes, who had largely trained himself in surveying

work, cut the excessively large number of scientists down to nine. He then reserved for himself, and other naval officers, some of the scientific duties, including all those connected with surveying

and cartography

.

Personnel included naturalist

s, botanists, a mineralogist, taxidermists and a philologist, and was carried by the sloops-of-war

, of 780 tons, and of 650 tons, the brig

, of 230 tons, the full-rigged ship Relief

, which served as a store-ship, and two schooner

s, Sea Gull

, of 110 tons and of 96 tons which served as tender

s.

Upon clearing the Cape Henry Light at 09:00 on Saturday, August 19, 1838, Wilkes laid in his course for Rio de Janeiro

Upon clearing the Cape Henry Light at 09:00 on Saturday, August 19, 1838, Wilkes laid in his course for Rio de Janeiro

. By orders, he was to survey certain reported vigias, or shoals at latitude 10° south

and between longitudes 18°

and 22° west

. Due to the prevailing winds at this season, the squadron made an easterly tack of the Atlantic.

The squadron arrived at the harbor of Funchal

in the Madeira Islands on September 16, 1838. After completing some repairs the group moved southward and arrived on October 7 at the bay of Porto Praya, Cape Verde Islands, eventually arriving at Rio de Janeiro on November 23. The entire passage from the United States to Brazil taking ninety-five days, about twice the time normally for a vessel proceeding directly. Due to repairs needed by the Peacock, the Squadron did not leave Rio de Janerio until January 6, 1839. From there they moved southward to Buenos Aires

and the mouth of the Río Negro, passing a French

naval blockade of Argentina

's seaports. The Europe

an powers at the time, with the aid of Brazil, were involved in the internal affairs of the Argentine Republic. However, since the Americans had reduced its military profile prior to its departure from the United States, they were not molested by the French warships.

Following this beginning, the squadron visited Tierra del Fuego

, Chile

, and Peru

. The USS Sea Gull and its crew of fifteen were lost during a South American coastal storm in May, 1839. From South America

, the expedition visited the Tuamotu Archipelago, Samoa

and New South Wales

, Australia

. In December 1839, the expedition sailed from Sydney

into the Antarctic Ocean and reported the discovery "of an Antarctic continent west of the Balleny Islands

". That part of Antarctica was later named Wilkes Land

. Because of discrepancies in the logs of the various ships of the Wilkes expedition, and suggestions that these may have been subsequently altered, it is uncertain whether the Wilkes expedition, or the French expedition of Jules Dumont d'Urville

, was the first to sight the Antarctic mainland coast in this vicinity. The controversy was added to by the actions of the commander of the USS Porpoise, Lieutenant Cadwalader Ringgold

, who, after sighting d'Urville's Astrolabe deliberately avoided contact.

In February 1840, some of the expedition were present at the initial signing of the Treaty of Waitangi

in New Zealand

.

After sighting the Astrolabe, the expedition visited Fiji

. In July 1840, two members of the party, Lieutenant Underwood and Wilkes' nephew, Midshipman Wilkes Henry, were killed while bartering for food in western Fiji

's Malolo

Island. The cause of this event remains equivocal. Immediately prior to their deaths the son of the local chief, who was being held as a hostage by the Americans, escaped by jumping out of the boat and running through the shallow water for shore. The Americans fired over his head. According to members of the expedition party on the boat, his escape was intended as a prearranged signal by the Fijians to attack. According to those on shore the shooting actually precipitated the attack on the ground. The Americans landed sixty sailors to attack the hostile natives. Close to eighty Fijians were killed in the resulting American reprisal and two villages were burned to the ground.

In 1841, the expedition explored the west coast of South America

and North America

, including the Strait of Juan de Fuca

, Puget Sound

, and the Columbia River

.

After Fiji, the expedition sailed to Hull Island, later known as Orona, and the Hawaiian Islands

. Like his predecessor, British

explorer George Vancouver

, Wilkes spent a good deal of time near Bainbridge Island. He noted the bird-like shape of the harbor at Winslow

and named it Eagle Harbor

. Continuing his fascination with bird names, he named Bill Point and Wing Point. Port Madison, Washington and Points Monroe and Jefferson named in honor of former United States presidents. Port Ludlow

was assigned to honor Lieutenant Augustus Ludlow

, who lost his life during the War of 1812

.

In April 1842 USS Peacock, under Lieutenant William L. Hudson

, and USS Flying Fish, surveyed Drummond's Island

, which was named for an American of the expedition. Lieutenant Hudson heard from a member of his crew that a ship had wrecked off the island and her crew massacred by the Gilbertese

. A woman and her child were said to be the only survivors so Hudson decided to land a small force of marines and sailors, under William M. Walker, to search the island. Initially the natives were peaceful and the Americans were able to explore the island, without results, it was when the party was returning to their ship that Hudon noticed a member of his crew was missing. After making another search the man was not found and the natives began arming themselves. Lieutenant Walker returned his force to the ship, to converse with Hudson, who ordered Walker to return to shore and demand the return of the sailor. Walker then reboarded his boats with his landing party and headed to shore. Walker shouted his demand and the natives charged for him, forcing the boats to turn back to the ships. It was decided on the next day that the Americans would bombard

the hostiles and land again. While doing this a force of around 700 Gilbertese warriors opposed the American assault but were defeated after a long battle. No Americans were hurt but twelve natives were killed and others were wounded, two villages were also destroyed. A similar episode occurred two months before in February when the Peacock and the Flying Fish briefly bombarded

the island of Upolu

, Samoa

following the death of an American merchant sailor on the island.

The Peacock was lost in July 1841 on the Columbia River

, though with no loss of life, thanks to a canoe rescue by John Dean, an African American servant of the Vincennes purser, and a group of Chinook

Indians. Dean also rescued the expedition's artist, Alfred Agate, along with his paintings and drawings. Upon learning that the Peacock had foundered on the Columbia River Bar, Wilkes interrupted his work in the San Juan Islands

and sailed south. He never returned to Puget Sound

.

From the area of modern-day Portland, Oregon

, an overland party headed by George F. Emmons

was directed to proceed via an inland route to San Francisco Bay

. This Emmons party traveled south along the Siskiyou Trail

, including the Sacramento River

, making the first official recorded visit by Americans to and scientific note of Mount Shasta

, in northern California.

The Emmons party rejoined the ships, which had sailed south, in San Francisco Bay

. The expedition then headed back out into the Pacific, including a visit to Wake Island

in 1841, and returned by way of the Philippines

, the Sulu Archipelago

, Borneo

, Singapore

, Polynesia

and the Cape of Good Hope

, reaching New York on June 10, 1842.

The expedition throughout was plagued by poor relationships between Wilkes and his subordinate officers. Wilkes' self-proclaimed status as captain" and commodore, accompanied by the flying of the requisite pennant and the wearing of a captain's uniform while being commissioned only as a Lieutenant, rankled heavily with other members of the expedition of similar real rank. His apparent mistreatment of many of his subordinates, and indulgence in punishments such as "flogging round the fleet" resulted in a major controversy on his return to America. Wilkes was court-martial

led on his return, but was acquitted on all charges except that of illegally punishing men in his squadron.

on Zoophytes, of 1846, Geology, 1849, and Crustacea of 1852 to 1854. In addition to many shorter articles and reports, Wilkes published the major scientific works Western America, including California and Oregon, 1849, and Theory of the Winds of 1856. The Smithsonian Institution digitized the five volume Narrative and the accompanying scientific volumes.

The Wilkes Expedition played a major role in development of 19th-century science, particularly in the growth of the American scientific establishment. Many of the species and other items found by the expedition helped form the basis of collections at the new Smithsonian Institution

The Wilkes Expedition played a major role in development of 19th-century science, particularly in the growth of the American scientific establishment. Many of the species and other items found by the expedition helped form the basis of collections at the new Smithsonian Institution

.

With the help of the expedition's scientists, derisively called "clam diggers" and "bug catchers" by navy crew members, 280 islands, mostly in the Pacific, were explored, and over 800 miles of Oregon

were mapped. Of no less importance, over 60,000 plant and bird specimens were collected. A staggering amount of data and specimens were collected during the expedition, including the seeds of 648 species, which were later traded, planted, and sent throughout the country. Dried specimens were sent to the National Herbarium, now a part of the Smithsonian Institution. There were also 254 live plants, which mostly came from the home stretch of the journey, that were placed in a newly constructed greenhouse in 1850, which later became the United States Botanic Garden

.

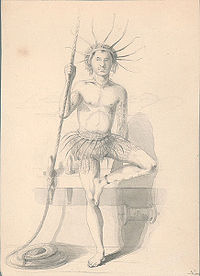

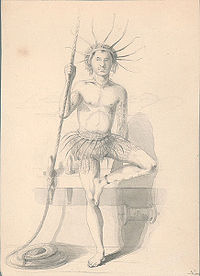

Alfred Thomas Agate, engraver and illustrator, created an enduring record of traditional cultures such as the illustrations made of the dress and tattoo patterns of natives of the Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu

).

A collection of artifacts from the expedition also went to the National Institute for the Promotion of Science

, a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. These joined artifacts from American history as the first artifacts in the Smithsonian collection.

are set on a fictional 7th ship accompanying the expedition.

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

and surrounding lands conducted by the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

from 1838 to 1842. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones

Thomas ap Catesby Jones

Thomas ap Catesby Jones was a U.S. Navy officer during the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War.-Early life:Jones was born in 1790 in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Thomas ap Catesby Jones means Thomas, son of Catesby Jones in the Welsh language. His brother was Roger Jones, who would become...

. The voyage was authorized by Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

in 1836. It is sometimes called the "U.S. Ex. Ex." for short, or the "Wilkes Expedition" in honor of its next appointed commanding officer, United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes was an American naval officer and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 and commanded the ship in the Trent Affair during the American Civil War...

. The expedition was of major importance to the growth of science in the United States, in particular the then-young field of oceanography

Oceanography

Oceanography , also called oceanology or marine science, is the branch of Earth science that studies the ocean...

. During the event, armed conflict between Pacific islanders and the expedition was not uncommon and dozens of natives were killed in action, as well as a few Americans.

Preparations

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States . He served as an American diplomat, Senator, and Congressional representative. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of former...

, voted to send an expedition around the world with the understanding that the country would derive great benefit. It was to promote commerce and to offer protection to the heavy investment in the whaling

Whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales mainly for meat and oil. Its earliest forms date to at least 3000 BC. Various coastal communities have long histories of sustenance whaling and harvesting beached whales...

and seal hunting

Seal hunting

Seal hunting, or sealing, is the personal or commercial hunting of seals. The hunt is currently practiced in five countries: Canada, where most of the world's seal hunting takes place, Namibia, the Danish region of Greenland, Norway and Russia...

industries, chiefly in the Pacific Ocean. Congress also agreed that a public ship or ships should be used. At the time, the only ships owned by the government capable of such a circumnavigation

Circumnavigation

Circumnavigation – literally, "navigation of a circumference" – refers to travelling all the way around an island, a continent, or the entire planet Earth.- Global circumnavigation :...

were those of the navy. So, in fact, Congress had decided that a naval expedition be authorized. There were to be many unforeseen impediments and it was not until May 18, 1836, that an act was passed, which authorized funding. Even with the burden of finance lifted, there were another two years of alteration of formation and command before six oddly assorted ships moved down from Norfolk to Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

on August 9, 1838. On August 17, after being joined by the tenders Sea Gull and Flying-Fish which delivered Lieutenant Wilkes final orders and at 15:00 hours the afternoon of August 18 the vessels weighed anchor. Due to light breezes the expedition did not discharge their pilots until 09:00 August 19 when they passed Cape Henry Light. By 11:00 the small fleet was standing to open seas.

Originally the expedition was first organized under Commodore Jones, however he subsequently resigned the station. Several more senior officers had either resigned from or indicated their unwillingness to accept command of the expedition. Command was finally vested in Lieutenant Wilkes. The three duties laid down were daunting to officers trained only in fighting ships. In addition to exploration, the naval squadron was tasked with the duties to survey both the newly found areas and survey other areas previously discovered, but about which there was insufficient knowledge. As well, a scientific corps, of all civilians, was to be included an additional command responsibility. There were few officers in the American navy at that time with any surveying experience and none with a background of working alongside scientists. The United States Coast Survey, where most of the surveyors were employed and learned their trade, was a civilian organization. Wilkes, who had largely trained himself in surveying

Surveying

See Also: Public Land Survey SystemSurveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, and science of accurately determining the terrestrial or three-dimensional position of points and the distances and angles between them...

work, cut the excessively large number of scientists down to nine. He then reserved for himself, and other naval officers, some of the scientific duties, including all those connected with surveying

Surveying

See Also: Public Land Survey SystemSurveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, and science of accurately determining the terrestrial or three-dimensional position of points and the distances and angles between them...

and cartography

Cartography

Cartography is the study and practice of making maps. Combining science, aesthetics, and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.The fundamental problems of traditional cartography are to:*Set the map's...

.

Personnel included naturalist

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

s, botanists, a mineralogist, taxidermists and a philologist, and was carried by the sloops-of-war

Sloop-of-war

In the 18th and most of the 19th centuries, a sloop-of-war was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. As the rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above, this meant that the term sloop-of-war actually encompassed all the unrated combat vessels including the...

, of 780 tons, and of 650 tons, the brig

Brig

A brig is a sailing vessel with two square-rigged masts. During the Age of Sail, brigs were seen as fast and manoeuvrable and were used as both naval warships and merchant vessels. They were especially popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries...

, of 230 tons, the full-rigged ship Relief

USS Relief (1836)

The first USS Relief was a supply ship in the United States Navy.Relief was laid down in 1835 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and launched on 14 September 1836. Designed by Samuel Humphreys, she was built along merchant vessel lines and included trysail mast and gaffsail on all three masts to enable...

, which served as a store-ship, and two schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

s, Sea Gull

USS Sea Gull (1838)

USS Sea Gull was a schooner in the service of the United States Navy. The Sea Gull was one of six ships that sailed in the US Exploring Expedition in 1838 to survey the coast of the then-unknown continent of Antarctica and the Pacific Islands...

, of 110 tons and of 96 tons which served as tender

Ship's tender

A ship's tender, usually referred to as a tender, is a boat, or a larger ship used to service a ship, generally by transporting people and/or supplies to and from shore or another ship...

s.

Route of the expedition

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro , commonly referred to simply as Rio, is the capital city of the State of Rio de Janeiro, the second largest city of Brazil, and the third largest metropolitan area and agglomeration in South America, boasting approximately 6.3 million people within the city proper, making it the 6th...

. By orders, he was to survey certain reported vigias, or shoals at latitude 10° south

10th parallel south

The 10th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 10 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlantic Ocean, Africa, the Indian Ocean, Australasia, the Pacific Ocean and South America....

and between longitudes 18°

18th meridian west

The meridian 18° west of Greenwich is a line of longitude that extends from the North Pole across the Arctic Ocean, Greenland, Iceland, the Atlantic Ocean, the Canary Islands, the Southern Ocean, and Antarctica to the South Pole....

and 22° west

22nd meridian west

The meridian 22° west of Greenwich is a line of longitude that extends from the North Pole across the Arctic Ocean, Greenland, Iceland, the Atlantic Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and Antarctica to the South Pole....

. Due to the prevailing winds at this season, the squadron made an easterly tack of the Atlantic.

The squadron arrived at the harbor of Funchal

Funchal

Funchal is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Autonomous Region of Madeira. The city has a population of 112,015 and has been the capital of Madeira for more than five centuries.-Etymology:...

in the Madeira Islands on September 16, 1838. After completing some repairs the group moved southward and arrived on October 7 at the bay of Porto Praya, Cape Verde Islands, eventually arriving at Rio de Janeiro on November 23. The entire passage from the United States to Brazil taking ninety-five days, about twice the time normally for a vessel proceeding directly. Due to repairs needed by the Peacock, the Squadron did not leave Rio de Janerio until January 6, 1839. From there they moved southward to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires is the capital and largest city of Argentina, and the second-largest metropolitan area in South America, after São Paulo. It is located on the western shore of the estuary of the Río de la Plata, on the southeastern coast of the South American continent...

and the mouth of the Río Negro, passing a French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

naval blockade of Argentina

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

's seaports. The Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an powers at the time, with the aid of Brazil, were involved in the internal affairs of the Argentine Republic. However, since the Americans had reduced its military profile prior to its departure from the United States, they were not molested by the French warships.

Following this beginning, the squadron visited Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of a main island Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego divided between Chile and Argentina with an area of , and a group of smaller islands including Cape...

, Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

, and Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

. The USS Sea Gull and its crew of fifteen were lost during a South American coastal storm in May, 1839. From South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

, the expedition visited the Tuamotu Archipelago, Samoa

Samoa

Samoa , officially the Independent State of Samoa, formerly known as Western Samoa is a country encompassing the western part of the Samoan Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. It became independent from New Zealand in 1962. The two main islands of Samoa are Upolu and one of the biggest islands in...

and New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

. In December 1839, the expedition sailed from Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

into the Antarctic Ocean and reported the discovery "of an Antarctic continent west of the Balleny Islands

Balleny Islands

The Balleny Islands are a series of uninhabited islands in the Southern Ocean extending from 66°15' to 67°35'S and 162°30' to 165°00'E. The group extends for about in a northwest-southeast direction. The islands are heavily glaciated and are of volcanic origin. Glaciers project from their slopes...

". That part of Antarctica was later named Wilkes Land

Wilkes Land

Wilkes Land is a large district of land in eastern Antarctica, formally claimed by Australia as part of the Australian Antarctic Territory, though the validity of this claim has been placed for the period of the operation of the Antarctic Treaty, to which Australia is a signatory...

. Because of discrepancies in the logs of the various ships of the Wilkes expedition, and suggestions that these may have been subsequently altered, it is uncertain whether the Wilkes expedition, or the French expedition of Jules Dumont d'Urville

Jules Dumont d'Urville

Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville was a French explorer, naval officer and rear admiral, who explored the south and western Pacific, Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica.-Childhood:Dumont was born at Condé-sur-Noireau...

, was the first to sight the Antarctic mainland coast in this vicinity. The controversy was added to by the actions of the commander of the USS Porpoise, Lieutenant Cadwalader Ringgold

Cadwalader Ringgold

Cadwalader Ringgold was an officer in the United States Navy who served in the United States Exploring Expedition, later headed an expedition to the Northwest and, after initially retiring, returned to service during the Civil War....

, who, after sighting d'Urville's Astrolabe deliberately avoided contact.

In February 1840, some of the expedition were present at the initial signing of the Treaty of Waitangi

Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi is a treaty first signed on 6 February 1840 by representatives of the British Crown and various Māori chiefs from the North Island of New Zealand....

in New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

.

After sighting the Astrolabe, the expedition visited Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

. In July 1840, two members of the party, Lieutenant Underwood and Wilkes' nephew, Midshipman Wilkes Henry, were killed while bartering for food in western Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

's Malolo

Malolo

Malolo is a volcanic island located in the Mamanuca Group of Fiji. It is an inhabited island, but focuses on tourism and offers many resorts and other vacation spots. There are many activities offered, including snorkeling, boating, and sight-seeing.-History:...

Island. The cause of this event remains equivocal. Immediately prior to their deaths the son of the local chief, who was being held as a hostage by the Americans, escaped by jumping out of the boat and running through the shallow water for shore. The Americans fired over his head. According to members of the expedition party on the boat, his escape was intended as a prearranged signal by the Fijians to attack. According to those on shore the shooting actually precipitated the attack on the ground. The Americans landed sixty sailors to attack the hostile natives. Close to eighty Fijians were killed in the resulting American reprisal and two villages were burned to the ground.

In 1841, the expedition explored the west coast of South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

and North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

, including the Strait of Juan de Fuca

Strait of Juan de Fuca

The Strait of Juan de Fuca is a large body of water about long that is the Salish Sea outlet to the Pacific Ocean...

, Puget Sound

Puget Sound

Puget Sound is a sound in the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected marine waterways and basins, with one major and one minor connection to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Pacific Ocean — Admiralty Inlet being the major connection and...

, and the Columbia River

Columbia River

The Columbia River is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, Canada, flows northwest and then south into the U.S. state of Washington, then turns west to form most of the border between Washington and the state...

.

After Fiji, the expedition sailed to Hull Island, later known as Orona, and the Hawaiian Islands

Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, numerous smaller islets, and undersea seamounts in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some 1,500 miles from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kure Atoll...

. Like his predecessor, British

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

explorer George Vancouver

George Vancouver

Captain George Vancouver RN was an English officer of the British Royal Navy, best known for his 1791-95 expedition, which explored and charted North America's northwestern Pacific Coast regions, including the coasts of contemporary Alaska, British Columbia, Washington and Oregon...

, Wilkes spent a good deal of time near Bainbridge Island. He noted the bird-like shape of the harbor at Winslow

Winslow, Washington

Winslow is the name of the downtown area of the city of Bainbridge Island, Washington, and is the original name of the city. It encompasses the area around the main street, Winslow Way, and is made up of approximately overlooking Eagle Harbor....

and named it Eagle Harbor

Eagle Harbor

Eagle Harbor may refer to a water body or community in the United States:* Eagle Harbor , an inlet in Bainbridge Island at the community of Winslow, Washington** Eagle Harbor High School* Eagle Harbor, Maryland* Eagle Harbor Township, Michigan...

. Continuing his fascination with bird names, he named Bill Point and Wing Point. Port Madison, Washington and Points Monroe and Jefferson named in honor of former United States presidents. Port Ludlow

Port Ludlow, Washington

Port Ludlow is a census-designated place in Jefferson County, Washington, United States. It is also the name of the marine inlet on which the CDP is located. The CDP's population was 1,968 at the 2000 census. Originally a logging and sawmill community, its economy declined during the first half of...

was assigned to honor Lieutenant Augustus Ludlow

Augustus Ludlow

Augustus C. Ludlow was an officer in the United States Navy during the War of 1812.-Biography:Ludlow, born Newburgh, New York, was appointed midshipmen 2 April 1804 and commissioned Lieutenant 3 June 1810...

, who lost his life during the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

.

In April 1842 USS Peacock, under Lieutenant William L. Hudson

William L. Hudson

Captain William Levereth Hudson, USN was a United States Navy officer in the first half of the 19th century.-Career:Hudson was born 11 May 1794 in Brooklyn...

, and USS Flying Fish, surveyed Drummond's Island

Tabiteuea

Tabiteuea is an atoll in the Gilbert Islands, Kiribati, south of Tarawa. The atoll consists of two main islands: Eanikai in the north, Nuguti in the south, and several smaller islets in between along the eastern rim of the atoll. The atoll has a total land area of 38 km², while the lagoon measures...

, which was named for an American of the expedition. Lieutenant Hudson heard from a member of his crew that a ship had wrecked off the island and her crew massacred by the Gilbertese

Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands are a chain of sixteen atolls and coral islands in the Pacific Ocean. They are the main part of Republic of Kiribati and include Tarawa, the site of the country's capital and residence of almost half of the population.-Geography:The atolls and islands of the Gilbert Islands...

. A woman and her child were said to be the only survivors so Hudson decided to land a small force of marines and sailors, under William M. Walker, to search the island. Initially the natives were peaceful and the Americans were able to explore the island, without results, it was when the party was returning to their ship that Hudon noticed a member of his crew was missing. After making another search the man was not found and the natives began arming themselves. Lieutenant Walker returned his force to the ship, to converse with Hudson, who ordered Walker to return to shore and demand the return of the sailor. Walker then reboarded his boats with his landing party and headed to shore. Walker shouted his demand and the natives charged for him, forcing the boats to turn back to the ships. It was decided on the next day that the Americans would bombard

Battle of Drummond's Island

The Battle of Drummond's Island occurred during the American exploring expedition in April 1841 at Tabiteuea, then known as Drummond's Island...

the hostiles and land again. While doing this a force of around 700 Gilbertese warriors opposed the American assault but were defeated after a long battle. No Americans were hurt but twelve natives were killed and others were wounded, two villages were also destroyed. A similar episode occurred two months before in February when the Peacock and the Flying Fish briefly bombarded

Bombardment of Upolu

The Bombardment of Upolu, in 1841, was the second engagement with islanders of the Pacific Ocean during the United States exploring expedition. Following the murder of an American sailor on the island of Upolu, Samoa, two United States Navy warships were despatched to protect American lives and...

the island of Upolu

Upolu

Upolu is an island in Samoa, formed by a massive basaltic shield volcano which rises from the seafloor of the western Pacific Ocean. The island is long, in area, and is the second largest in geographic area as well as the most populated of the Samoan Islands. Upolu is situated to the east of...

, Samoa

Samoa

Samoa , officially the Independent State of Samoa, formerly known as Western Samoa is a country encompassing the western part of the Samoan Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. It became independent from New Zealand in 1962. The two main islands of Samoa are Upolu and one of the biggest islands in...

following the death of an American merchant sailor on the island.

The Peacock was lost in July 1841 on the Columbia River

Columbia River

The Columbia River is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, Canada, flows northwest and then south into the U.S. state of Washington, then turns west to form most of the border between Washington and the state...

, though with no loss of life, thanks to a canoe rescue by John Dean, an African American servant of the Vincennes purser, and a group of Chinook

Chinookan

Chinook refers to several native amercain groups of in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, speaking the Chinookan languages. In the early 19th century, the Chinookan-speaking peoples lived along the lower and middle Columbia River in present-day Oregon and Washington...

Indians. Dean also rescued the expedition's artist, Alfred Agate, along with his paintings and drawings. Upon learning that the Peacock had foundered on the Columbia River Bar, Wilkes interrupted his work in the San Juan Islands

San Juan Islands

The San Juan Islands are an archipelago in the northwest corner of the contiguous United States between the US mainland and Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. The San Juan Islands are part of the U.S...

and sailed south. He never returned to Puget Sound

Puget Sound

Puget Sound is a sound in the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected marine waterways and basins, with one major and one minor connection to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Pacific Ocean — Admiralty Inlet being the major connection and...

.

From the area of modern-day Portland, Oregon

Portland, Oregon

Portland is a city located in the Pacific Northwest, near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers in the U.S. state of Oregon. As of the 2010 Census, it had a population of 583,776, making it the 29th most populous city in the United States...

, an overland party headed by George F. Emmons

George F. Emmons

George Foster Emmons was a rear admiral of the United States Navy, who served in the early to mid 19th century.-Biography:Born in Clarendon, Vermont, Emmons began his distinguished career as a midshipman on 1 April 1828...

was directed to proceed via an inland route to San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a shallow, productive estuary through which water draining from approximately forty percent of California, flowing in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers from the Sierra Nevada mountains, enters the Pacific Ocean...

. This Emmons party traveled south along the Siskiyou Trail

Siskiyou Trail

The Siskiyou Trail stretched from California's Central Valley to Oregon's Willamette Valley; modern-day Interstate 5 follows this pioneer path...

, including the Sacramento River

Sacramento River

The Sacramento River is an important watercourse of Northern and Central California in the United States. The largest river in California, it rises on the eastern slopes of the Klamath Mountains, and after a journey south of over , empties into Suisun Bay, an arm of the San Francisco Bay, and...

, making the first official recorded visit by Americans to and scientific note of Mount Shasta

Mount Shasta

Mount Shasta is located at the southern end of the Cascade Range in Siskiyou County, California and at is the second highest peak in the Cascades and the fifth highest in California...

, in northern California.

The Emmons party rejoined the ships, which had sailed south, in San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay is a shallow, productive estuary through which water draining from approximately forty percent of California, flowing in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers from the Sierra Nevada mountains, enters the Pacific Ocean...

. The expedition then headed back out into the Pacific, including a visit to Wake Island

Wake Island

Wake Island is a coral atoll having a coastline of in the North Pacific Ocean, located about two-thirds of the way from Honolulu west to Guam east. It is an unorganized, unincorporated territory of the United States, administered by the Office of Insular Affairs, U.S. Department of the Interior...

in 1841, and returned by way of the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

, the Sulu Archipelago

Sulu Archipelago

The Sulu Archipelago is a chain of islands in the southwestern Philippines. This archipelago is considered to be part of the Moroland by the local rebel independence movement. This island group forms the northern limit of the Celebes Sea....

, Borneo

Borneo

Borneo is the third largest island in the world and is located north of Java Island, Indonesia, at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia....

, Singapore

Singapore

Singapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

, Polynesia

Polynesia

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of over 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are termed Polynesians and they share many similar traits including language, culture and beliefs...

and the Cape of Good Hope

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa.There is a misconception that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Africa, because it was once believed to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In fact, the...

, reaching New York on June 10, 1842.

The expedition throughout was plagued by poor relationships between Wilkes and his subordinate officers. Wilkes' self-proclaimed status as captain" and commodore, accompanied by the flying of the requisite pennant and the wearing of a captain's uniform while being commissioned only as a Lieutenant, rankled heavily with other members of the expedition of similar real rank. His apparent mistreatment of many of his subordinates, and indulgence in punishments such as "flogging round the fleet" resulted in a major controversy on his return to America. Wilkes was court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

led on his return, but was acquitted on all charges except that of illegally punishing men in his squadron.

The publication program

For a short time Wilkes was attached to the Coast Survey, but from 1844 to 1861 he was chiefly engaged in preparing the report of the expedition. Twenty-eight volumes were planned but only nineteen were published. Of these Wilkes wrote the Narrative of 1845 and the volumes Hydrography and Meteorology of 1851. The Narrative contains much interesting material concerning the manners and customs and political and economic conditions in many places then little known. Other valuable contributions were the three reports of James Dwight DanaJames Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana was an American geologist, mineralogist and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcanic activity, and the origin and structure of continents and oceans around the world.-Early life and career:...

on Zoophytes, of 1846, Geology, 1849, and Crustacea of 1852 to 1854. In addition to many shorter articles and reports, Wilkes published the major scientific works Western America, including California and Oregon, 1849, and Theory of the Winds of 1856. The Smithsonian Institution digitized the five volume Narrative and the accompanying scientific volumes.

Significance of the expedition

Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution is an educational and research institute and associated museum complex, administered and funded by the government of the United States and by funds from its endowment, contributions, and profits from its retail operations, concessions, licensing activities, and magazines...

.

With the help of the expedition's scientists, derisively called "clam diggers" and "bug catchers" by navy crew members, 280 islands, mostly in the Pacific, were explored, and over 800 miles of Oregon

Oregon

Oregon is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located on the Pacific coast, with Washington to the north, California to the south, Nevada on the southeast and Idaho to the east. The Columbia and Snake rivers delineate much of Oregon's northern and eastern...

were mapped. Of no less importance, over 60,000 plant and bird specimens were collected. A staggering amount of data and specimens were collected during the expedition, including the seeds of 648 species, which were later traded, planted, and sent throughout the country. Dried specimens were sent to the National Herbarium, now a part of the Smithsonian Institution. There were also 254 live plants, which mostly came from the home stretch of the journey, that were placed in a newly constructed greenhouse in 1850, which later became the United States Botanic Garden

United States Botanic Garden

The United States Botanic Garden is a botanic garden on the grounds of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., near Garfield Circle....

.

Alfred Thomas Agate, engraver and illustrator, created an enduring record of traditional cultures such as the illustrations made of the dress and tattoo patterns of natives of the Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu

Tuvalu

Tuvalu , formerly known as the Ellice Islands, is a Polynesian island nation located in the Pacific Ocean, midway between Hawaii and Australia. Its nearest neighbours are Kiribati, Nauru, Samoa and Fiji. It comprises four reef islands and five true atolls...

).

A collection of artifacts from the expedition also went to the National Institute for the Promotion of Science

National Institute for the Promotion of Science

The National Institution for the Promotion of Science organization was established in Washington, D.C. in May, 1840, and was heir to the mantle of the earlier Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences...

, a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. These joined artifacts from American history as the first artifacts in the Smithsonian collection.

The expedition in popular culture

The Wiki Coffin novels of Joan DruettJoan Druett

Joan Druett is a New Zealand historian and novelist, specialising in maritime history.-Life:Joan Druett was born in Nelson, and raised in Palmerston North, moving to New Zealand's capital city, Wellington, when she was 16...

are set on a fictional 7th ship accompanying the expedition.

Ships

- USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

, 780 tons, 18 guns, sloop-of-warSloop-of-warIn the 18th and most of the 19th centuries, a sloop-of-war was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. As the rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above, this meant that the term sloop-of-war actually encompassed all the unrated combat vessels including the...

, flagshipFlagshipA flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, reflecting the custom of its commander, characteristically a flag officer, flying a distinguishing flag... - USS Peacock, 650 tons, 22 guns, sloop-of-war

- USS ReliefUSS Relief (1836)The first USS Relief was a supply ship in the United States Navy.Relief was laid down in 1835 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and launched on 14 September 1836. Designed by Samuel Humphreys, she was built along merchant vessel lines and included trysail mast and gaffsail on all three masts to enable...

, 468 tons, 7 guns, full-rigged ship - USS PorpoiseUSS Porpoise (1836)The second USS Porpoise was a 224-ton Dolphin class brigantine The USS Porpoise was later rerigged as a brig...

, 230 tons, 10 guns, brigBrigA brig is a sailing vessel with two square-rigged masts. During the Age of Sail, brigs were seen as fast and manoeuvrable and were used as both naval warships and merchant vessels. They were especially popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries... - USS Sea GullUSS Sea Gull (1838)USS Sea Gull was a schooner in the service of the United States Navy. The Sea Gull was one of six ships that sailed in the US Exploring Expedition in 1838 to survey the coast of the then-unknown continent of Antarctica and the Pacific Islands...

, 110 tons, 2 guns, schoonerSchoonerA schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts.... - USS Flying FishUSS Flying Fish (1838)USS Flying Fish , a schooner, was formerly the New York City pilot boat Independence. Purchased by the United States Navy at New York City on 3 August 1838 and upon joining her squadron in Hampton Roads 12 August 1838 was placed under command of Passed Midshipman S. R. Knox.Assigned as a tender in...

, 96 tons, 2 guns, schooner

Naval Officers

- James Alden

- Thomas A. Budd, cartographer;

- Overton Carr

- George M. ColvocoressesGeorge ColvocoressesGeorge Musalas "Colvos" Colvocoresses was a United States Navy officer who commanded the USS Saratoga during the American Civil War. From 1838 up until 1842, he served in the United States Exploring Expedition, better known as the Wilkes Expedition, which explored large regions of the Pacific Ocean...

(1816–1872), midshipman; - Thomas T. Craven

- Samuel Dinsman, marine;

- Henry EldHenry EldHenry Eld was born in Cedar Hill, New Haven, Connecticut, on June 2, 1814, and lived in the area now known as View Street, but when it started becoming more populated he removed his house and relocated. He was a Lieutenant in the U.S...

(1814–1850), midshipman; - George Elliott, ship's boy;

- Jared Elliott, ship's chaplain;

- Samuel Elliott, midshipman; USS PorpoiseUSS Porpoise (1836)The second USS Porpoise was a 224-ton Dolphin class brigantine The USS Porpoise was later rerigged as a brig...

- George Foster EmmonsGeorge F. EmmonsGeorge Foster Emmons was a rear admiral of the United States Navy, who served in the early to mid 19th century.-Biography:Born in Clarendon, Vermont, Emmons began his distinguished career as a midshipman on 1 April 1828...

(1811–1884), lieutenant; - Thomas Ford, seaman;

- Dr. John L. Fox, ship's doctor; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

- Charles GuillouCharles GuillouCharles Fleury Bien-aimé Guilloû was an American military physician. He served on a major exploring expedition that included both scientific discoveries and controversy, and two historic diplomatic missions...

, ship's doctor; - George Hammersly, midshipman;

- James Henderson, quartermaster; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

- Silas Holmes;

- William L. Hudson, commanding officer;

- Robert E. Johnson, lieutenant;

- Samuel R. Knox, commanding officer; USS Flying FishUSS Flying Fish (1838)USS Flying Fish , a schooner, was formerly the New York City pilot boat Independence. Purchased by the United States Navy at New York City on 3 August 1838 and upon joining her squadron in Hampton Roads 12 August 1838 was placed under command of Passed Midshipman S. R. Knox.Assigned as a tender in...

- A. K. Long, commanding officer; USS ReliefUSS Relief (1836)The first USS Relief was a supply ship in the United States Navy.Relief was laid down in 1835 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and launched on 14 September 1836. Designed by Samuel Humphreys, she was built along merchant vessel lines and included trysail mast and gaffsail on all three masts to enable...

- William Lewis Maury (1813–1878)

- James H. North, acting master; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

- James W. E. Reid, commanding officer; USS Sea GullUSS Sea Gull (1838)USS Sea Gull was a schooner in the service of the United States Navy. The Sea Gull was one of six ships that sailed in the US Exploring Expedition in 1838 to survey the coast of the then-unknown continent of Antarctica and the Pacific Islands...

- William ReynoldsWilliam Reynolds (naval officer)-External links:* : Franklin & Marshall College...

(1815–1879), - Cadwalader RinggoldCadwalader RinggoldCadwalader Ringgold was an officer in the United States Navy who served in the United States Exploring Expedition, later headed an expedition to the Northwest and, after initially retiring, returned to service during the Civil War....

(1802–1867), commanding officer; USS PorpoiseUSS Porpoise (1836)The second USS Porpoise was a 224-ton Dolphin class brigantine The USS Porpoise was later rerigged as a brig... - R. B. Robinson, purser's clerk; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

- George Rogers, marine;

- George T. Sinclair, sailing master; USS PorpoiseUSS Porpoise (1836)The second USS Porpoise was a 224-ton Dolphin class brigantine The USS Porpoise was later rerigged as a brig...

- Simeon Stearns, marine sergeant;

- George M. Totten, midshipman, cartographer;

- Richard Russell WaldronRichard Russell WaldronRichard Russell Waldron was a purser "and special agent" in the Wilkes Expedition, together with younger brother Thomas Westbrook Waldron . Cape Waldron in Antarctica, and perhaps Waldron Island in Washington state, were named after him. Waldron Ledge overlooking the Hawaiian Kilauea Crater is...

, purser, USS Vincennes, and special agent - Thomas W. WaldronThomas Westbrook Waldron (consul)]Thomas Westbrook Waldron was a captain's clerk on the Wilkes Expedition, and the first United States consul to Hong Kong. His service to the United States consular service was honoured by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton during a ceremony in 2009...

, captain's clerk, USS Porpoise - Henry Waltham, seaman;

- Charles WilkesCharles WilkesCharles Wilkes was an American naval officer and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 and commanded the ship in the Trent Affair during the American Civil War...

(1798–1877), commander of expedition - J. D. Winn, Sailing Master;

Engravers & Illustrators

- Alfred Thomas Agate (1812–1846), engraver and illustrator; USS ReliefUSS Relief (1836)The first USS Relief was a supply ship in the United States Navy.Relief was laid down in 1835 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and launched on 14 September 1836. Designed by Samuel Humphreys, she was built along merchant vessel lines and included trysail mast and gaffsail on all three masts to enable...

- Joseph Drayton (1795–1856), engraver and illustrator; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

Scientific Corps

- William Dunlop BrackenridgeWilliam Dunlop BrackenridgeWilliam Dunlop Brackenridge was a Scottish nurseryman and botanist.Brackenridge emigrated to Philadelphia in 1837, where he was employed by Robert Buist, nurseryman. He was appointed horticulturalist, then assistant botanist, for the United States Exploring Expedition from 1838-1842...

(1810–1893), assistant botanist; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was... - John G. Brown, mathematical instrument maker; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

- Joseph Pitty CouthouyJoseph Pitty CouthouyJoseph Pitty Couthouy was an American naval officer, conchologist, and invertebrate palaeontologist. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, he entered the Boston Latin School in 1820. He married Mary Greenwood Wild on 9 March 1832.Couthouy applied to President Andrew Jackson for a position on the...

(1808–1864), conchologist; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was... - James Dwight DanaJames Dwight DanaJames Dwight Dana was an American geologist, mineralogist and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcanic activity, and the origin and structure of continents and oceans around the world.-Early life and career:...

(1813–1895), mineralogist and geologistGeologistA geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

; USS Peacock - F. L. Davenport, interpreter; USS Peacock

- John Dean

- John W. W. Dyes, assistant taxidermist; USS VincennesUSS Vincennes (1826)USS Vincennes was a 703-ton Boston-class sloop of war in the United States Navy from 1826 to 1865. During her service, Vincennes patrolled the Pacific, explored the Antarctic, and blockaded the Confederate Gulf coast in the Civil War. Named for the Revolutionary War Battle of Vincennes, she was...

- Horatio Emmons HaleHoratio HaleHoratio Emmons Hale was an American-Canadian ethnologist, philologist and businessman who studied language as a key for classifying ancient peoples and being able to trace their migrations...

(1817–1896), philologist; USS Peacock - Titian Ramsay PealeTitian PealeTitian Ramsay Peale was a noted American artist, naturalist, entomologist and photographer. He was the sixteenth child and youngest son of noted American naturalist Charles Willson Peale.-Biography:...

(1799–1885), naturalistNatural historyNatural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

; USS Peacock - Charles PickeringCharles Pickering (naturalist)Charles Pickering was an American naturalist.Born in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, the grandson of Colonel Timothy Pickering, he grew up in Wenham, Massachusetts and received a medical degree from Harvard University in 1823...

(1805–1878), naturalistNatural historyNatural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

; - William RichWilliam RichMajor William Rich was an American botanist and explorer who was part of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842.William Rich was the youngest son of Captain Obadiah Rich who commanded the brig Intrepid in the American Revolutionary War, and his first wife Salome Lombard...

, botanist; USS ReliefUSS Relief (1836)The first USS Relief was a supply ship in the United States Navy.Relief was laid down in 1835 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard and launched on 14 September 1836. Designed by Samuel Humphreys, she was built along merchant vessel lines and included trysail mast and gaffsail on all three masts to enable... - Henry Wilkes

External links

- The United States Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842 — from the Smithsonian Institution Libraries Digital Collections

- Google Books

- Material from the Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

- Museum of the Siskiyou Trail