USS Chesapeake (1799)

Encyclopedia

USS Chesapeake was a 38-gun wooden-hull

ed, three-masted

heavy frigate

of the United States Navy

. She was one of the original six frigates whose construction was authorized by the Naval Act of 1794

. Joshua Humphreys

designed these frigates to be the young navy's capital ship

s. Chesapeake was originally designed as a 44-gun frigate but construction delays, material shortages, and budget problems caused builder Josiah Fox

to alter her design to 38 guns. Launched at the Gosport Navy Yard on 2 December 1799, Chesapeake began her career during the Quasi-War

with France and saw service in the First Barbary War

.

On 22 June 1807 she was fired upon by of the Royal Navy

for refusing to comply with a search for deserters. The event, now known as the Chesapeake–Leopard Affair

, angered the American populace and government and was a precipitating factor that led to the War of 1812

. As a result of the affair, Chesapeakes commanding officer, James Barron

, was court-martial

ed and the United States instituted the Embargo Act of 1807

against England.

Early in the War of 1812

she made one patrol and captured five British merchant ships before returning. She was captured by shortly after sailing from Boston, Massachusetts, on 1 June 1813. The Royal Navy took her into their service as HMS Chesapeake, where she served until she was broken up and her timbers sold in 1820; they are now part of the Chesapeake Mill

in Wickham

, England.

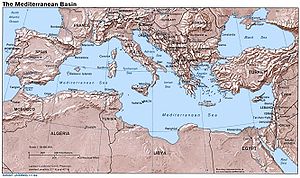

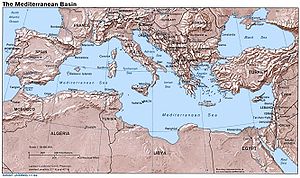

s began to fall prey to Barbary Pirates

, most notably from Algiers

, in the Mediterranean during the 1790s. Congress responded with the Naval Act of 1794

. The Act provided funds for the construction of six frigates, and directed that the construction would continue unless and until the United States agreed to peace terms with Algiers.An Act to provide a Naval Armament. (1794). Library of Congress

. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

Joshua Humphreys

' design was long on keel

and narrow of beam

(width) to allow for the mounting of very heavy guns. The design incorporated a diagonal scantling

(rib) scheme to limit hogging (warping) and included extremely heavy planking. This gave the hull

greater strength than those of more lightly built frigates. Since the fledgling United States could not match the numbers of ships of the European states, Humphreys designed his frigates to be able to overpower other frigates, but with the speed to escape from a ship of the line

.

Originally designated as "Frigate D", the ship remained unnamed for several years. Her keel was laid down in December 1795 at the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virginia, where Josiah Fox

had been appointed her naval constructor and Richard Dale

as superintendent of construction.

In March 1796 a peace accord was announced between the United States and Algiers and construction was suspended in accordance with the Naval Act of 1794. The keel remained on blocks in the navy yard for two years.

The onset of the Quasi-War

with France in 1798 prompted Congress to authorize completion of "Frigate D", and they approved resumption of the work on 16 July. When Fox returned to Norfolk he discovered a shortage of timber caused by its diversion from Norfolk to Baltimore in order to finish . He corresponded with Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert

, who indicated a desire to expedite construction of the ship and reduce the overall cost. Fox, always an opponent of Humphreys's large design, submitted new plans to Stoddert which called for utilizing the existing keel but reducing the overall dimensions substantially in length and partially of beam. Fox's plans essentially proposed an entirely different design than originally planned by Humphreys. Secretary Stoddert approved the new design plans.

When construction finished, she had the smallest dimensions of the six frigates. A length of 152.8 ft (46.6 m) between perpendiculars and 41.3 ft (12.6 m) of beam contrasted with her closest sisters, and Constellation, which were built to 164 ft (50 m) in length and 41 ft (12.5 m) of beam. The final cost of her construction was $220,677—the second-least expensive frigate of the six. The least expensive was Congress at $197,246.

During construction, a sloop named Chesapeake was launched on 20 June 1799 but was renamed between 10 October and 14 November, apparently to free up the name Chesapeake for "Frigate D". In communications between Fox and Stoddert, Fox repeatedly referred to her as Congress, further confusing matters, until he was informed by Stoddert the ship was to be named Chesapeake, after Chesapeake Bay

. She was the only one of the six frigates not named by President George Washington

, nor after a principle of the United States Constitution.

directed Captain Samuel Evans to recruit the number of crewmen required for a 44-gun ship. Hamilton was corrected by William Bainbridge

in a letter stating, "There is a mistake in the crew ordered for the Chesapeake, as it equals in number the crews of our 44-gun frigates, whereas the Chesapeake is of the class of the Congress and Constellation."

Gun ratings did not correspond to the actual number of guns a ship would carry. Chesapeake was noted as carrying 40 guns during her encounter with and 50 guns during her engagement with in 1813. The 50 guns consisted of twenty-eight 18-pounder (8 kg) long guns on the gun deck

, fourteen on each side. This main battery was complemented by two long 12-pounders (5.5 kg), one long 18-pounder, eighteen 32-pounder (14.5 kg) carronade

s, and one 12-pound carronade on the spar deck. Her broadside

weight was 542 pounds (245.8 kg).

The ships of this era had no permanent battery of guns; guns were completely portable and were often exchanged between ships as situations warranted. Each commanding officer modified his vessel's armaments to his liking while taking into consideration factors such as the overall tonnage of cargo, complement of personnel aboard, and planned routes to be sailed. Consequently, a vessel's armament would change often during its career; records of the changes were not generally kept.

on 2 December 1799 during the undeclared Quasi-War (1798–1800), which arose after the French navy seized American merchant ships. Her fitting-out

continued through May 1800. In March Josiah Fox was reprimanded by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert

for continuing to work on Chesapeake while Congress, still awaiting completion, was fully manned with a crew drawing pay. Stoddert appointed Thomas Truxton to ensure that his directives concerning Congress were carried out.

Chesapeake first put to sea on 22 May commanded by Captain Samuel Barron and marked her departure from Norfolk with a 13-gun salute. Her first assignment was to carry currency from Charleston, South Carolina, to Philadelphia. On 6 June she joined a squadron patrolling off the southern coast of the United States and in the West Indies escorting American merchant ships.

Capturing the 16-gun French privateer

La Jeune Creole on 1 January 1801 after a chase lasting 50 hours, she returned to Norfolk with her prize

on 15 January. Chesapeake returned briefly to the West Indies in February, soon after a peace treaty was ratified with France. She returned to Norfolk and decommissioned on 26 February, subsequently being placed in reserve

.

During the Quasi-War, the United States had paid tribute

During the Quasi-War, the United States had paid tribute

to the Barbary States

to ensure that they would not seize or harass American merchant ships. In 1801 Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli

, dissatisfied with the amount of tribute in comparison to that paid to Algiers, demanded an immediate payment of $250,000. Thomas Jefferson

responded by sending a squadron of warships to protect American merchant ships in the Mediterranean and to pursue peace negotiations with the Barbary States. The first squadron was under the command of Richard Dale

in President and the second was assigned to the command of Richard Valentine Morris

in Chesapeake. Morris's squadron eventually consisted of the vessels Constellation, , , , and . It took several months to prepare the vessels for sea; they departed individually as they became ready.

Chesapeake departed from Hampton Roads on 27 April 1802 and arrived at Gibraltar

on 25 May; she immediately put in for repairs, as her main mast had split during the voyage. Morris remained at Gibraltar while awaiting word on the location of his squadron, as several ships had not reported in. On 22 July Adams arrived with belated orders for Morris, dated 20 April. Those orders were to "lay the whole squadron before Tripoli" and negotiate peace. Chesapeake and Enterprise departed Gibraltar on 17 August bound for Leghorn

, while providing protection for a convoy of merchant ships that were bound for intermediate ports. Morris made several stops in various ports before finally arriving at Leghorn on 12 October, after which he sailed to Malta

. Chesapeake undertook repairs of a rotted bowsprit

. Chesapeake was still in port when John Adams arrived on 5 January 1803 with orders dated 23 October 1802 from Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith. These directed Chesapeake and Constellation to return to the United States; Morris was to transfer his command to New York. Constellation sailed directly as ordered, but Morris retained Chesapeake at Malta, claiming that she was not in any condition to make an Atlantic voyage during the winter months.

Morris now had the ships New York, John Adams, and Enterprise gathered under him, while Adams was at Gibraltar. On 30 January Chesapeake and the squadron got underway for Tripoli, where Morris planned to burn Tripolitan

ships in the harbor. Heavy gales made the approach to Tripoli difficult. Fearing Chesapeake would lose her masts from the strong winds, Morris returned to Malta on 10 February. With provisions for the ships running low and none available near Malta, Morris decided to abandon plans to blockade Tripoli and sailed the squadron back to Gibraltar for provisioning. They made stops at Tunis

on 22 February and Algiers on 19 March. Chesapeake arrived at Gibraltar on 23 March, where Morris transferred his command to New York. Under James Barron

, Chesapeake sailed for the United States on 7 April and she was placed in reserve at the Washington Navy Yard

on 1 June.

Morris remained in the Mediterranean until September, when orders from Secretary Smith arrived suspending his command and instructing him to return to the United States. There he faced a Naval Board of Inquiry

which found that he was censurable for "inactive and dilatory conduct of the squadron under his command". He was dismissed from the navy in 1804. Morris's overall performance in the Mediterranean was particularly criticized for the state of affairs aboard Chesapeake and his inactions as a commander. His wife, young son, and housekeeper accompanied him on the voyage, during which Mrs. Morris gave birth to another son. Midshipman Henry Wadsworth wrote that he and the other midshipman referred to Mrs. Morris as the "Commodoress" and believed she was the main reason behind Chesapeake remaining in port for months at a time. Consul William Eaton reported to Secretary Smith that Morris and his squadron spent more time in port sightseeing and doing little but "dance and wench" than blockading Tripoli.

into Royal Navy service from the beginning. He therefore refused to release them back to Melampus and nothing further was communicated on the subject.

In early June Chesapeake departed the Washington Navy Yard for Norfolk, Virginia, where she completed provisioning and loading armaments. Captain Gordon informed Barron on the 19th that Chesapeake was ready for sea and they departed on 22 June armed with 40 guns. At the same time, a British squadron consisting of HMS Melampus, , and (a 50-gun fourth-rate

) were lying off the port of Norfolk blockading two French ships there. As Chesapeake departed, the squadron ships began signaling each other and Leopard got under way preceding Chesapeake to sea.

After sailing for some hours, Leopard, commanded by Captain Salusbury Pryce Humphreys

, approached Chesapeake and hailed a request to deliver dispatches to England, a customary request of the time. When a British lieutenant arrived by boat he handed Barron an order, given by Vice-Admiral George Berkeley

of the Royal Navy, which instructed the British ships to stop and board Chesapeake to search for deserters. Barron refused to allow this search, and as the lieutenant returned to Leopard Barron ordered the crew to general quarters

. Shortly afterward Leopard hailed Chesapeake; Barron could not understand the message. Leopard fired a shot across the bow, followed by a broadside

, at Chesapeake. For fifteen minutes, while Chesapeake attempted to arm herself, Leopard continued to fire broadside after broadside until Barron struck his colors

. Chesapeake only managed to fire one retaliatory shot after hot coals from the galley were brought on deck to ignite the cannon. The British boarded Chesapeake and carried off four crewmen, declining Barron's offer that Chesapeake be taken as a prize of war. Chesapeake had three sailors killed and Barron was among the 18 wounded.

Word of the incident spread quickly upon Chesapeakes return to Norfolk, where the British squadron that included Leopard was provisioning. Mobs of angry citizens destroyed two hundred water casks destined for the squadron and nearly killed a British lieutenant before local authorities intervened. President Jefferson recalled all US warships from the Mediterranean and issued a proclamation: all British warships were banned from entering US ports and those already in port were to depart. The incident eventually led to the Embargo Act of 1807

.

Chesapeake was completely unprepared to defend herself during the incident. None of her guns were primed for operation and the spar deck was filled with materials that were not properly stowed in the cargo hold. A court-martial was convened for Barron and Captain Gordon, as well as Lieutenant Hall of the Marines. Barron was found guilty of "neglecting on the probability of an engagement to clear his Ship for action" and suspended from the navy for five years. Gordon and Hall were privately reprimanded, and the ship's gunner was discharged from the navy.

, she made patrols off the New England coast enforcing the laws of the Embargo Act throughout 1809.

The Chesapeake–Leopard Affair, and later the Little Belt Affair

, contributed to the United States' decision to declare war on Britain on 18 June 1812. Chesapeake, under the command of Captain Samuel Evans, was prepared for duty in the Atlantic. Beginning on 13 December, she ranged from Madeira

and traveled clockwise to the Cape Verde Islands and South America, and then back to Boston. She captured six ships as prizes: the British ships Volunteer, Liverpool Hero, Earl Percy, and Ellen; the brig Julia, an American ship trading under a British license; and Valeria, an American ship recaptured from British privateers. During the cruise she was chased by an unknown British ship-of-the-line and frigate but, after a passing storm squall, the two pursuing ships were gone the next morning. The cargo of Volunteer, 40 tons of pig iron and copper, sold for $185,000. Earl Percy never made it back to port as she ran aground off the coast of Long Island, and Liverpool Hero was burned as she was considered leaky. Chesapeakes total monetary damage to British shipping was $235,675. She returned to Boston on 9 April 1813 for refitting.

Captain Evans, now in poor health, requested relief of command. Captain James Lawrence

, late of the and her victory over , took command of Chesapeake on 20 May. Affairs of the ship were in poor condition. The term of enlistment for many of the crew had expired and they were daily leaving the ship. Those who remained were disgruntled and approaching mutiny, as the prize money they were owed from her previous cruise was held up in court. Lawrence paid out the prize money from his own pocket in order to appease them. Some sailors from Constitution joined Chesapeake and they filled the crew along with sailors of several nations.

Meanwhile Captain Philip Broke

and HMS Shannon

, a 38-gun frigate, were patrolling off the port of Boston on blockade duty. Shannon had been under the command of Broke since 1806 and, under his direction, the crew held daily gun and weapon drills lasting up to three hours. Crew members who hit their bullseye were awarded a pound (454 g) of tobacco for their good marksmanship. In this regard Chesapeake, with her new and inexperienced crew, was greatly inferior.

Leaving port with a broad white flag bearing the motto "Free Trade and Sailors' Rights", Chesapeake met with Shannon near 5 pm that afternoon. During six minutes of firing, each ship managed two full broadsides. Chesapeake damaged Shannon with her broadsides but suffered early in the exchange. A succession of helmsmen were killed at the wheel and she lost maneuverability.

Captain Broke brought Shannon alongside Chesapeake and ordered the two ships lashed together to enable his crew to board Chesapeake. Confusion and disarray reigned on the deck of Chesapeake; Captain Lawrence tried rallying a party to board Shannon, but the bugler failed to sound the call. At this point a shot from a sniper mortally wounded Lawrence; as his men carried him below, he gave his last order: "Don't give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks." During the exchange of cannonfire 362 shots struck Chesapeake, while only 158 hit Shannon.

Captain Broke boarded Chesapeake at the head of a party of 20 men. They met little resistance from Chesapeakes crew, most of whom had run below deck. The only resistance from Chesapeake came from her contingent of marines. The British soon overwhelmed them; only nine escaped injury out of 44. Captain Broke was severely injured in the fighting on the forecastle, being struck in the head with a sword. Soon after, Shannons crew pulled down Chesapeakes flag. Only 15 minutes had elapsed from the first exchange of gunfire to the capture.

Reports on the number of killed and wounded aboard Chesapeake during the battle vary widely. Broke's after-action report from 6 July states 70 killed and 100 wounded. Contemporary sources place the number between 48–61 killed and 85–99 wounded. Discrepancies in the number of killed and wounded are possibly caused by the addition of sailors who died of their wounds in the ensuing days after the battle. The counts for Shannon have fewer discrepancies with 23 killed; 56 wounded. Despite his serious injuries, Broke ordered repairs to both ships and they proceeded on to Halifax, Nova Scotia

. Captain Lawrence died en route and was buried in Halifax with military honors. The British imprisoned his crew. Captain Broke survived his wounds and was later made a baronet

.

, South Africa, until learning of the peace treaty

with the United States in May 1815. Upon returning to England later in the year, Chesapeake went into reserve and apparently never returned to active duty. In 1819 she was sold to a Portsmouth timber merchant for £500 who dismantled the ship and sold its timbers to Joshua Holmes for £3,450. Eventually her timbers became part of the Chesapeake Mill

in Wickham

, Hampshire, England, where they can be viewed to this day.

Almost from her beginnings, Chesapeake was considered an "unlucky ship", the "runt of the litter" to the superstitious sailors of the 19th century, and the product of a disagreement between Humphreys and Fox. Her ill-fated encounters with HMS Leopard and Shannon, the court martials of two of her captains, and the accidental deaths of several crewmen led many to believe she was cursed.

Arguments defending both Humphreys and Fox regarding their long-standing disagreements over the design of the frigates carried on for years. Humphreys disowned any credit for Fox's redesign of Chesapeake. In 1827 he wrote, "She [Chesapeake] spoke his [Fox's] talents. Which I leave the Commanders of that ship to estimate by her qualifications."

Lawrence's last command of "Don't give up the ship!" became a rallying cry for the US Navy. Oliver Hazard Perry

, in command of naval forces on Lake Erie during September 1813, named his flagship

, which flew a broad blue flag bearing the words " give up the ship!" The phrase is still used in the US Navy today, as displayed on the .

Chesapeakes blood-stained and bullet-ridden American flag was sold at auction in London in 1908. Purchased by William Waldorf Astor

, it now resides in the National Maritime Museum

in Greenwich

, England, along with her signal book. The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic

in Halifax, Nova Scotia, holds several artifacts of the battle with Shannon. In 1996 a timber fragment from the Chesapeake Mill was returned to the United States. It is on display at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum

.

Hull (watercraft)

A hull is the watertight body of a ship or boat. Above the hull is the superstructure and/or deckhouse, where present. The line where the hull meets the water surface is called the waterline.The structure of the hull varies depending on the vessel type...

ed, three-masted

Mast (sailing)

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall, vertical, or near vertical, spar, or arrangement of spars, which supports the sails. Large ships have several masts, with the size and configuration depending on the style of ship...

heavy frigate

Frigate

A frigate is any of several types of warship, the term having been used for ships of various sizes and roles over the last few centuries.In the 17th century, the term was used for any warship built for speed and maneuverability, the description often used being "frigate-built"...

of the United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

. She was one of the original six frigates whose construction was authorized by the Naval Act of 1794

Naval Act of 1794

The Act to Provide a Naval Armament, also known as the Naval Act, was passed by the United States Congress on March 27, 1794 and established the country's first naval force, which eventually became the United States Navy...

. Joshua Humphreys

Joshua Humphreys

Joshua Humphreys was an influential and successful ship builder in the United States.Humphreys was born in Haverford, Pennsylvania and died in the same place. He is the son of Daniel Humphreys and Hannah Wynne . He was brother to Charles Humphreys...

designed these frigates to be the young navy's capital ship

Capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they generally possess the heaviest firepower and armor and are traditionally much larger than other naval vessels...

s. Chesapeake was originally designed as a 44-gun frigate but construction delays, material shortages, and budget problems caused builder Josiah Fox

Josiah Fox

Josiah Fox was a Cornish naval architect noted for his involvement in the design and construction of the first significant warships of the United States Navy....

to alter her design to 38 guns. Launched at the Gosport Navy Yard on 2 December 1799, Chesapeake began her career during the Quasi-War

Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war fought mostly at sea between the United States and French Republic from 1798 to 1800. In the United States, the conflict was sometimes also referred to as the Franco-American War, the Pirate Wars, or the Half-War.-Background:The Kingdom of France had been a...

with France and saw service in the First Barbary War

First Barbary War

The First Barbary War , also known as the Barbary Coast War or the Tripolitan War, was the first of two wars fought between the United States and the North African Berber Muslim states known collectively as the Barbary States...

.

On 22 June 1807 she was fired upon by of the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

for refusing to comply with a search for deserters. The event, now known as the Chesapeake–Leopard Affair

Chesapeake–Leopard Affair

The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair was a naval engagement which occurred off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia on June 22, 1807, between the British warship HMS Leopard and the American frigate, the USS Chesapeake, when the crew of the Leopard pursued, attacked and boarded the American frigate looking for...

, angered the American populace and government and was a precipitating factor that led to the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

. As a result of the affair, Chesapeakes commanding officer, James Barron

James Barron

James Barron was an officer in the United States Navy. Commander of the frigate USS Chesapeake, he was court-martialed for his actions on 22 June 1807, which led to the surrender of his ship to the British....

, was court-martial

Court-martial

A court-martial is a military court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the armed forces subject to military law, and, if the defendant is found guilty, to decide upon punishment.Most militaries maintain a court-martial system to try cases in which a breach of...

ed and the United States instituted the Embargo Act of 1807

Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 and the subsequent Nonintercourse Acts were American laws restricting American ships from engaging in foreign trade between the years of 1807 and 1812. The Acts were diplomatic responses by presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison designed to protect American interests...

against England.

Early in the War of 1812

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

she made one patrol and captured five British merchant ships before returning. She was captured by shortly after sailing from Boston, Massachusetts, on 1 June 1813. The Royal Navy took her into their service as HMS Chesapeake, where she served until she was broken up and her timbers sold in 1820; they are now part of the Chesapeake Mill

Chesapeake Mill

The Chesapeake Mill is a watermill in Wickham, Hampshire, England. The mill was designed and constructed in 1820 using the timbers of HMS Chesapeake, which had previously been the United States Navy frigate . Chesapeake had been captured by the Royal Navy frigate during the War of 1812. John Prior...

in Wickham

Wickham

Wickham, formerly spelled Wykeham, is a small historic village and civil parish in Hampshire, southern England, located about three miles north of Fareham. It is within the City of Winchester local government district, although it is considerably closer to Fareham than to Winchester...

, England.

Design and construction

American merchant vesselMerchant vessel

A merchant vessel is a ship that transports cargo or passengers. The closely related term commercial vessel is defined by the United States Coast Guard as any vessel engaged in commercial trade or that carries passengers for hire...

s began to fall prey to Barbary Pirates

Barbary corsairs

The Barbary Corsairs, sometimes called Ottoman Corsairs or Barbary Pirates, were pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Tunis, Tripoli and Algiers. This area was known in Europe as the Barbary Coast, a term derived from the name of its Berber...

, most notably from Algiers

Algiers

' is the capital and largest city of Algeria. According to the 1998 census, the population of the city proper was 1,519,570 and that of the urban agglomeration was 2,135,630. In 2009, the population was about 3,500,000...

, in the Mediterranean during the 1790s. Congress responded with the Naval Act of 1794

Naval Act of 1794

The Act to Provide a Naval Armament, also known as the Naval Act, was passed by the United States Congress on March 27, 1794 and established the country's first naval force, which eventually became the United States Navy...

. The Act provided funds for the construction of six frigates, and directed that the construction would continue unless and until the United States agreed to peace terms with Algiers.An Act to provide a Naval Armament. (1794). Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress is the research library of the United States Congress, de facto national library of the United States, and the oldest federal cultural institution in the United States. Located in three buildings in Washington, D.C., it is the largest library in the world by shelf space and...

. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

Joshua Humphreys

Joshua Humphreys

Joshua Humphreys was an influential and successful ship builder in the United States.Humphreys was born in Haverford, Pennsylvania and died in the same place. He is the son of Daniel Humphreys and Hannah Wynne . He was brother to Charles Humphreys...

' design was long on keel

Keel

In boats and ships, keel can refer to either of two parts: a structural element, or a hydrodynamic element. These parts overlap. As the laying down of the keel is the initial step in construction of a ship, in British and American shipbuilding traditions the construction is dated from this event...

and narrow of beam

Beam (nautical)

The beam of a ship is its width at the widest point. Generally speaking, the wider the beam of a ship , the more initial stability it has, at expense of reserve stability in the event of a capsize, where more energy is required to right the vessel from its inverted position...

(width) to allow for the mounting of very heavy guns. The design incorporated a diagonal scantling

Scantling

Scantling is a measurement of prescribed size, dimensions, or cross sectional areas. For comparison, see Form Factor: -Shipping:In shipbuilding, the scantling refers to the collective dimensions of the various parts, particularly the framing and structural supports. The word is most often used in...

(rib) scheme to limit hogging (warping) and included extremely heavy planking. This gave the hull

Hull (watercraft)

A hull is the watertight body of a ship or boat. Above the hull is the superstructure and/or deckhouse, where present. The line where the hull meets the water surface is called the waterline.The structure of the hull varies depending on the vessel type...

greater strength than those of more lightly built frigates. Since the fledgling United States could not match the numbers of ships of the European states, Humphreys designed his frigates to be able to overpower other frigates, but with the speed to escape from a ship of the line

Ship of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed from the 17th through the mid-19th century to take part in the naval tactic known as the line of battle, in which two columns of opposing warships would manoeuvre to bring the greatest weight of broadside guns to bear...

.

Originally designated as "Frigate D", the ship remained unnamed for several years. Her keel was laid down in December 1795 at the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virginia, where Josiah Fox

Josiah Fox

Josiah Fox was a Cornish naval architect noted for his involvement in the design and construction of the first significant warships of the United States Navy....

had been appointed her naval constructor and Richard Dale

Richard Dale

Richard Dale fought in the Continental Navy under John Barry and was first lieutenant for John Paul Jones during the naval battle off of Flamborough Head, England against the HMS Serapis in the celebrated engagement of...

as superintendent of construction.

In March 1796 a peace accord was announced between the United States and Algiers and construction was suspended in accordance with the Naval Act of 1794. The keel remained on blocks in the navy yard for two years.

The onset of the Quasi-War

Quasi-War

The Quasi-War was an undeclared war fought mostly at sea between the United States and French Republic from 1798 to 1800. In the United States, the conflict was sometimes also referred to as the Franco-American War, the Pirate Wars, or the Half-War.-Background:The Kingdom of France had been a...

with France in 1798 prompted Congress to authorize completion of "Frigate D", and they approved resumption of the work on 16 July. When Fox returned to Norfolk he discovered a shortage of timber caused by its diversion from Norfolk to Baltimore in order to finish . He corresponded with Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert

Benjamin Stoddert

Benjamin Stoddert was the first United States Secretary of the Navy from May 1, 1798 to March 31, 1801.-Early life:...

, who indicated a desire to expedite construction of the ship and reduce the overall cost. Fox, always an opponent of Humphreys's large design, submitted new plans to Stoddert which called for utilizing the existing keel but reducing the overall dimensions substantially in length and partially of beam. Fox's plans essentially proposed an entirely different design than originally planned by Humphreys. Secretary Stoddert approved the new design plans.

When construction finished, she had the smallest dimensions of the six frigates. A length of 152.8 ft (46.6 m) between perpendiculars and 41.3 ft (12.6 m) of beam contrasted with her closest sisters, and Constellation, which were built to 164 ft (50 m) in length and 41 ft (12.5 m) of beam. The final cost of her construction was $220,677—the second-least expensive frigate of the six. The least expensive was Congress at $197,246.

During construction, a sloop named Chesapeake was launched on 20 June 1799 but was renamed between 10 October and 14 November, apparently to free up the name Chesapeake for "Frigate D". In communications between Fox and Stoddert, Fox repeatedly referred to her as Congress, further confusing matters, until he was informed by Stoddert the ship was to be named Chesapeake, after Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

. She was the only one of the six frigates not named by President George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, nor after a principle of the United States Constitution.

Armament

Chesapeakes nominal rating is stated as either 36 or 38 guns. Originally designated as a 44-gun ship, her redesign by Fox led to a rerating, apparently based on her smaller dimensions when compared to Congress and Constellation. Joshua Humphreys may have rerated Chesapeake to 38 guns, or Secretary Stoddert rerated Congress and Constellation to 38 guns because they were larger than Chesapeake, which was rated to 36 guns. The most recent information on her rating is from the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, which states she was rerated "from 44 guns to 36, eventually increased to 38". Her gun rating remained a matter of confusion throughout her career; Fox used a 44-gun rating in his correspondence with Secretary Stoddert. In preparing for the War of 1812 Secretary of the Navy Paul HamiltonPaul Hamilton

Paul Hamilton was the 3rd United States Secretary of the Navy, from 1809 to 1813.Paul Hamilton was born in Saint Paul's Parish, South Carolina, on October 16, 1762. He left school at the age of sixteen due to financial problems...

directed Captain Samuel Evans to recruit the number of crewmen required for a 44-gun ship. Hamilton was corrected by William Bainbridge

William Bainbridge

William Bainbridge was a Commodore in the United States Navy, notable for his victory over HMS Java during the War of 1812.-Early life:...

in a letter stating, "There is a mistake in the crew ordered for the Chesapeake, as it equals in number the crews of our 44-gun frigates, whereas the Chesapeake is of the class of the Congress and Constellation."

Gun ratings did not correspond to the actual number of guns a ship would carry. Chesapeake was noted as carrying 40 guns during her encounter with and 50 guns during her engagement with in 1813. The 50 guns consisted of twenty-eight 18-pounder (8 kg) long guns on the gun deck

Gun deck

The term gun deck originally referred to a deck aboard a ship that was primarily used for the mounting of cannon to be fired in broadsides. However, on many smaller vessels such as frigates and unrated vessels the upper deck, forecastle and quarterdeck bore all of the cannons but were not referred...

, fourteen on each side. This main battery was complemented by two long 12-pounders (5.5 kg), one long 18-pounder, eighteen 32-pounder (14.5 kg) carronade

Carronade

The carronade was a short smoothbore, cast iron cannon, developed for the Royal Navy by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, UK. It was used from the 1770s to the 1850s. Its main function was to serve as a powerful, short-range anti-ship and anti-crew weapon...

s, and one 12-pound carronade on the spar deck. Her broadside

Broadside

A broadside is the side of a ship; the battery of cannon on one side of a warship; or their simultaneous fire in naval warfare.-Age of Sail:...

weight was 542 pounds (245.8 kg).

The ships of this era had no permanent battery of guns; guns were completely portable and were often exchanged between ships as situations warranted. Each commanding officer modified his vessel's armaments to his liking while taking into consideration factors such as the overall tonnage of cargo, complement of personnel aboard, and planned routes to be sailed. Consequently, a vessel's armament would change often during its career; records of the changes were not generally kept.

Quasi-War

Chesapeake was launchedShip naming and launching

The ceremonies involved in naming and launching naval ships are based in traditions thousands of years old.-Methods of launch:There are three principal methods of conveying a new ship from building site to water, only two of which are called "launching." The oldest, most familiar, and most widely...

on 2 December 1799 during the undeclared Quasi-War (1798–1800), which arose after the French navy seized American merchant ships. Her fitting-out

Fitting-out

Fitting-out, or "outfitting”, is the process in modern shipbuilding that follows the float-out of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her owners...

continued through May 1800. In March Josiah Fox was reprimanded by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert

Benjamin Stoddert

Benjamin Stoddert was the first United States Secretary of the Navy from May 1, 1798 to March 31, 1801.-Early life:...

for continuing to work on Chesapeake while Congress, still awaiting completion, was fully manned with a crew drawing pay. Stoddert appointed Thomas Truxton to ensure that his directives concerning Congress were carried out.

Chesapeake first put to sea on 22 May commanded by Captain Samuel Barron and marked her departure from Norfolk with a 13-gun salute. Her first assignment was to carry currency from Charleston, South Carolina, to Philadelphia. On 6 June she joined a squadron patrolling off the southern coast of the United States and in the West Indies escorting American merchant ships.

Capturing the 16-gun French privateer

Privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship authorized by a government by letters of marque to attack foreign shipping during wartime. Privateering was a way of mobilizing armed ships and sailors without having to spend public money or commit naval officers...

La Jeune Creole on 1 January 1801 after a chase lasting 50 hours, she returned to Norfolk with her prize

Prize (law)

Prize is a term used in admiralty law to refer to equipment, vehicles, vessels, and cargo captured during armed conflict. The most common use of prize in this sense is the capture of an enemy ship and its cargo as a prize of war. In the past, it was common that the capturing force would be allotted...

on 15 January. Chesapeake returned briefly to the West Indies in February, soon after a peace treaty was ratified with France. She returned to Norfolk and decommissioned on 26 February, subsequently being placed in reserve

Reserve fleet

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed, and thus partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; an equivalent expression in unofficial modern U.S....

.

First Barbary War

Tribute

A tribute is wealth, often in kind, that one party gives to another as a sign of respect or, as was often the case in historical contexts, of submission or allegiance. Various ancient states, which could be called suzerains, exacted tribute from areas they had conquered or threatened to conquer...

to the Barbary States

Barbary Coast

The Barbary Coast, or Barbary, was the term used by Europeans from the 16th until the 19th century to refer to much of the collective land of the Berber people. Today, the terms Maghreb and "Tamazgha" correspond roughly to "Barbary"...

to ensure that they would not seize or harass American merchant ships. In 1801 Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli

Tripoli

Tripoli is the capital and largest city in Libya. It is also known as Western Tripoli , to distinguish it from Tripoli, Lebanon. It is affectionately called The Mermaid of the Mediterranean , describing its turquoise waters and its whitewashed buildings. Tripoli is a Greek name that means "Three...

, dissatisfied with the amount of tribute in comparison to that paid to Algiers, demanded an immediate payment of $250,000. Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

responded by sending a squadron of warships to protect American merchant ships in the Mediterranean and to pursue peace negotiations with the Barbary States. The first squadron was under the command of Richard Dale

Richard Dale

Richard Dale fought in the Continental Navy under John Barry and was first lieutenant for John Paul Jones during the naval battle off of Flamborough Head, England against the HMS Serapis in the celebrated engagement of...

in President and the second was assigned to the command of Richard Valentine Morris

Richard Valentine Morris

Richard Valentine Morris was a United States Navy officer.-Life:He was the son of Lewis Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence....

in Chesapeake. Morris's squadron eventually consisted of the vessels Constellation, , , , and . It took several months to prepare the vessels for sea; they departed individually as they became ready.

Chesapeake departed from Hampton Roads on 27 April 1802 and arrived at Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

on 25 May; she immediately put in for repairs, as her main mast had split during the voyage. Morris remained at Gibraltar while awaiting word on the location of his squadron, as several ships had not reported in. On 22 July Adams arrived with belated orders for Morris, dated 20 April. Those orders were to "lay the whole squadron before Tripoli" and negotiate peace. Chesapeake and Enterprise departed Gibraltar on 17 August bound for Leghorn

Livorno

Livorno , traditionally Leghorn , is a port city on the Tyrrhenian Sea on the western edge of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of approximately 160,000 residents in 2009.- History :...

, while providing protection for a convoy of merchant ships that were bound for intermediate ports. Morris made several stops in various ports before finally arriving at Leghorn on 12 October, after which he sailed to Malta

Malta

Malta , officially known as the Republic of Malta , is a Southern European country consisting of an archipelago situated in the centre of the Mediterranean, south of Sicily, east of Tunisia and north of Libya, with Gibraltar to the west and Alexandria to the east.Malta covers just over in...

. Chesapeake undertook repairs of a rotted bowsprit

Bowsprit

The bowsprit of a sailing vessel is a pole extending forward from the vessel's prow. It provides an anchor point for the forestay, allowing the fore-mast to be stepped farther forward on the hull.-Origin:...

. Chesapeake was still in port when John Adams arrived on 5 January 1803 with orders dated 23 October 1802 from Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith. These directed Chesapeake and Constellation to return to the United States; Morris was to transfer his command to New York. Constellation sailed directly as ordered, but Morris retained Chesapeake at Malta, claiming that she was not in any condition to make an Atlantic voyage during the winter months.

Morris now had the ships New York, John Adams, and Enterprise gathered under him, while Adams was at Gibraltar. On 30 January Chesapeake and the squadron got underway for Tripoli, where Morris planned to burn Tripolitan

Karamanli dynasty

The Karamanli or Caramanli or Qaramanli or al-Qaramanli dynasty was a series of Pashas, of Turkish origin who ruled from 1711 to 1835 in Tripolitania . At their peak, the Karamanlis' influence reached Cyrenaica and Fezzan covering most of Libya. The founder of the dynasty was Pasha Ahmed Karamanli...

ships in the harbor. Heavy gales made the approach to Tripoli difficult. Fearing Chesapeake would lose her masts from the strong winds, Morris returned to Malta on 10 February. With provisions for the ships running low and none available near Malta, Morris decided to abandon plans to blockade Tripoli and sailed the squadron back to Gibraltar for provisioning. They made stops at Tunis

Tunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

on 22 February and Algiers on 19 March. Chesapeake arrived at Gibraltar on 23 March, where Morris transferred his command to New York. Under James Barron

James Barron

James Barron was an officer in the United States Navy. Commander of the frigate USS Chesapeake, he was court-martialed for his actions on 22 June 1807, which led to the surrender of his ship to the British....

, Chesapeake sailed for the United States on 7 April and she was placed in reserve at the Washington Navy Yard

Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy...

on 1 June.

Morris remained in the Mediterranean until September, when orders from Secretary Smith arrived suspending his command and instructing him to return to the United States. There he faced a Naval Board of Inquiry

Naval Board of Inquiry

A Naval Board of Inquiry is a type of investigative court proceeding conducted by the United States Navy after the occurrence of an unanticipated event that adversely affects the performance, or reputation, of the fleet or one of its ships or stations.- Convening the board :Depending on the...

which found that he was censurable for "inactive and dilatory conduct of the squadron under his command". He was dismissed from the navy in 1804. Morris's overall performance in the Mediterranean was particularly criticized for the state of affairs aboard Chesapeake and his inactions as a commander. His wife, young son, and housekeeper accompanied him on the voyage, during which Mrs. Morris gave birth to another son. Midshipman Henry Wadsworth wrote that he and the other midshipman referred to Mrs. Morris as the "Commodoress" and believed she was the main reason behind Chesapeake remaining in port for months at a time. Consul William Eaton reported to Secretary Smith that Morris and his squadron spent more time in port sightseeing and doing little but "dance and wench" than blockading Tripoli.

Chesapeake–Leopard Affair

In January 1807 Master Commandant Charles Gordon was appointed Chesapeakes commanding officer (Captain). He was ordered to prepare her for patrol and convoy duty in the Mediterranean to relieve her sister ship , which had been on duty there since 1803. James Barron was appointed overall commander of the squadron as its Commodore. Chesapeake was in much disarray from her multi-year period of inactivity and many months were required for repairs, provisioning, and recruitment of personnel. Lieutenant Arthur Sinclair was tasked with the recruiting. Among those chosen were three sailors who had deserted from . The British ambassador to the United States requested the return of the sailors. Barron found that, although they were indeed from Melampus, they had been impressedImpressment

Impressment, colloquially, "the Press", was the act of taking men into a navy by force and without notice. It was used by the Royal Navy, beginning in 1664 and during the 18th and early 19th centuries, in wartime, as a means of crewing warships, although legal sanction for the practice goes back to...

into Royal Navy service from the beginning. He therefore refused to release them back to Melampus and nothing further was communicated on the subject.

In early June Chesapeake departed the Washington Navy Yard for Norfolk, Virginia, where she completed provisioning and loading armaments. Captain Gordon informed Barron on the 19th that Chesapeake was ready for sea and they departed on 22 June armed with 40 guns. At the same time, a British squadron consisting of HMS Melampus, , and (a 50-gun fourth-rate

Fourth-rate

In the British Royal Navy, a fourth rate was, during the first half of the 18th century, a ship of the line mounting from 46 up to 60 guns. While the number of guns stayed subsequently in the same range up until 1817, after 1756 the ships of 50 guns and below were considered too weak to stand in...

) were lying off the port of Norfolk blockading two French ships there. As Chesapeake departed, the squadron ships began signaling each other and Leopard got under way preceding Chesapeake to sea.

After sailing for some hours, Leopard, commanded by Captain Salusbury Pryce Humphreys

Salusbury Pryce Humphreys

Sir Salusbury Pryce Humphreys, CB, KCH was an officer of the Royal Navy who saw service during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, rising to the rank of rear-admiral....

, approached Chesapeake and hailed a request to deliver dispatches to England, a customary request of the time. When a British lieutenant arrived by boat he handed Barron an order, given by Vice-Admiral George Berkeley

George Cranfield-Berkeley

Admiral Sir George Cranfield Berkeley GCB , often known as George Berkeley, was a highly experienced, popular, yet controversial naval officer and politician in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century Britain...

of the Royal Navy, which instructed the British ships to stop and board Chesapeake to search for deserters. Barron refused to allow this search, and as the lieutenant returned to Leopard Barron ordered the crew to general quarters

General quarters

General Quarters or Battle Stations is an announcement made aboard a naval warship to signal the crew to prepare for battle or imminent damage....

. Shortly afterward Leopard hailed Chesapeake; Barron could not understand the message. Leopard fired a shot across the bow, followed by a broadside

Broadside

A broadside is the side of a ship; the battery of cannon on one side of a warship; or their simultaneous fire in naval warfare.-Age of Sail:...

, at Chesapeake. For fifteen minutes, while Chesapeake attempted to arm herself, Leopard continued to fire broadside after broadside until Barron struck his colors

Striking the colors

Striking the colors is the universally recognized indication of surrender, particularly for ships at sea. Surrender is dated from the time the ensign is struck.-In international law:# "Colors. A national flag . The colors . ....

. Chesapeake only managed to fire one retaliatory shot after hot coals from the galley were brought on deck to ignite the cannon. The British boarded Chesapeake and carried off four crewmen, declining Barron's offer that Chesapeake be taken as a prize of war. Chesapeake had three sailors killed and Barron was among the 18 wounded.

Word of the incident spread quickly upon Chesapeakes return to Norfolk, where the British squadron that included Leopard was provisioning. Mobs of angry citizens destroyed two hundred water casks destined for the squadron and nearly killed a British lieutenant before local authorities intervened. President Jefferson recalled all US warships from the Mediterranean and issued a proclamation: all British warships were banned from entering US ports and those already in port were to depart. The incident eventually led to the Embargo Act of 1807

Embargo Act of 1807

The Embargo Act of 1807 and the subsequent Nonintercourse Acts were American laws restricting American ships from engaging in foreign trade between the years of 1807 and 1812. The Acts were diplomatic responses by presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison designed to protect American interests...

.

Chesapeake was completely unprepared to defend herself during the incident. None of her guns were primed for operation and the spar deck was filled with materials that were not properly stowed in the cargo hold. A court-martial was convened for Barron and Captain Gordon, as well as Lieutenant Hall of the Marines. Barron was found guilty of "neglecting on the probability of an engagement to clear his Ship for action" and suspended from the navy for five years. Gordon and Hall were privately reprimanded, and the ship's gunner was discharged from the navy.

War of 1812

After the heavy damage inflicted by Leopard, Chesapeake returned to Norfolk for repairs. Under the command of Stephen DecaturStephen Decatur

Stephen Decatur, Jr. , was an American naval officer notable for his many naval victories in the early 19th century. He was born on the eastern shore of Maryland, Worcester county, the son of a U.S. Naval Officer who served during the American Revolution. Shortly after attending college Decatur...

, she made patrols off the New England coast enforcing the laws of the Embargo Act throughout 1809.

The Chesapeake–Leopard Affair, and later the Little Belt Affair

Little Belt Affair

The Little Belt Affair was a naval battle on the night of May 16, 1811. It involved the United States frigate USS President and the British sixth-rate HMS Little Belt, a sloop-of-war, which had originally been the Danish ship Lillebælt, before being captured by the British in the 1807 Battle of...

, contributed to the United States' decision to declare war on Britain on 18 June 1812. Chesapeake, under the command of Captain Samuel Evans, was prepared for duty in the Atlantic. Beginning on 13 December, she ranged from Madeira

Madeira

Madeira is a Portuguese archipelago that lies between and , just under 400 km north of Tenerife, Canary Islands, in the north Atlantic Ocean and an outermost region of the European Union...

and traveled clockwise to the Cape Verde Islands and South America, and then back to Boston. She captured six ships as prizes: the British ships Volunteer, Liverpool Hero, Earl Percy, and Ellen; the brig Julia, an American ship trading under a British license; and Valeria, an American ship recaptured from British privateers. During the cruise she was chased by an unknown British ship-of-the-line and frigate but, after a passing storm squall, the two pursuing ships were gone the next morning. The cargo of Volunteer, 40 tons of pig iron and copper, sold for $185,000. Earl Percy never made it back to port as she ran aground off the coast of Long Island, and Liverpool Hero was burned as she was considered leaky. Chesapeakes total monetary damage to British shipping was $235,675. She returned to Boston on 9 April 1813 for refitting.

Captain Evans, now in poor health, requested relief of command. Captain James Lawrence

James Lawrence

James Lawrence was an American naval officer. During the War of 1812, he commanded the USS Chesapeake in a single-ship action against HMS Shannon...

, late of the and her victory over , took command of Chesapeake on 20 May. Affairs of the ship were in poor condition. The term of enlistment for many of the crew had expired and they were daily leaving the ship. Those who remained were disgruntled and approaching mutiny, as the prize money they were owed from her previous cruise was held up in court. Lawrence paid out the prize money from his own pocket in order to appease them. Some sailors from Constitution joined Chesapeake and they filled the crew along with sailors of several nations.

Meanwhile Captain Philip Broke

Philip Broke

Rear Admiral Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke, 1st Baronet KCB was a distinguished officer in the British Royal Navy.-Early life:Broke was born at Broke Hall, Nacton, near Ipswich, the eldest son of Philip Bowes Broke...

and HMS Shannon

HMS Shannon (1806)

HMS Shannon was a 38-gun Leda-class frigate of the Royal Navy. She was launched in 1806 and served in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812...

, a 38-gun frigate, were patrolling off the port of Boston on blockade duty. Shannon had been under the command of Broke since 1806 and, under his direction, the crew held daily gun and weapon drills lasting up to three hours. Crew members who hit their bullseye were awarded a pound (454 g) of tobacco for their good marksmanship. In this regard Chesapeake, with her new and inexperienced crew, was greatly inferior.

Chesapeake vs Shannon

Lawrence, advised that Shannon had moved in closer to Boston, began preparations to sail on the evening of 31 May. The next morning Broke wrote a challenge to Lawrence and dispatched it to Chesapeake; it did not arrive before Lawrence set out to meet Shannon on his own accord.Leaving port with a broad white flag bearing the motto "Free Trade and Sailors' Rights", Chesapeake met with Shannon near 5 pm that afternoon. During six minutes of firing, each ship managed two full broadsides. Chesapeake damaged Shannon with her broadsides but suffered early in the exchange. A succession of helmsmen were killed at the wheel and she lost maneuverability.

Captain Broke brought Shannon alongside Chesapeake and ordered the two ships lashed together to enable his crew to board Chesapeake. Confusion and disarray reigned on the deck of Chesapeake; Captain Lawrence tried rallying a party to board Shannon, but the bugler failed to sound the call. At this point a shot from a sniper mortally wounded Lawrence; as his men carried him below, he gave his last order: "Don't give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks." During the exchange of cannonfire 362 shots struck Chesapeake, while only 158 hit Shannon.

Captain Broke boarded Chesapeake at the head of a party of 20 men. They met little resistance from Chesapeakes crew, most of whom had run below deck. The only resistance from Chesapeake came from her contingent of marines. The British soon overwhelmed them; only nine escaped injury out of 44. Captain Broke was severely injured in the fighting on the forecastle, being struck in the head with a sword. Soon after, Shannons crew pulled down Chesapeakes flag. Only 15 minutes had elapsed from the first exchange of gunfire to the capture.

Reports on the number of killed and wounded aboard Chesapeake during the battle vary widely. Broke's after-action report from 6 July states 70 killed and 100 wounded. Contemporary sources place the number between 48–61 killed and 85–99 wounded. Discrepancies in the number of killed and wounded are possibly caused by the addition of sailors who died of their wounds in the ensuing days after the battle. The counts for Shannon have fewer discrepancies with 23 killed; 56 wounded. Despite his serious injuries, Broke ordered repairs to both ships and they proceeded on to Halifax, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

. Captain Lawrence died en route and was buried in Halifax with military honors. The British imprisoned his crew. Captain Broke survived his wounds and was later made a baronet

Baronet

A baronet or the rare female equivalent, a baronetess , is the holder of a hereditary baronetcy awarded by the British Crown...

.

Royal Navy service and legacy

The Royal Navy repaired Chesapeake and took her into service as HMS Chesapeake. She served on the Halifax station under the command of Alexander Gordon through 1814, and under the command of George Burdett she sailed to Plymouth, England, for repairs in October of that year. Afterward she made a voyage to Cape TownCape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

, South Africa, until learning of the peace treaty

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent , signed on 24 December 1814, in Ghent , was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

with the United States in May 1815. Upon returning to England later in the year, Chesapeake went into reserve and apparently never returned to active duty. In 1819 she was sold to a Portsmouth timber merchant for £500 who dismantled the ship and sold its timbers to Joshua Holmes for £3,450. Eventually her timbers became part of the Chesapeake Mill

Chesapeake Mill

The Chesapeake Mill is a watermill in Wickham, Hampshire, England. The mill was designed and constructed in 1820 using the timbers of HMS Chesapeake, which had previously been the United States Navy frigate . Chesapeake had been captured by the Royal Navy frigate during the War of 1812. John Prior...

in Wickham

Wickham

Wickham, formerly spelled Wykeham, is a small historic village and civil parish in Hampshire, southern England, located about three miles north of Fareham. It is within the City of Winchester local government district, although it is considerably closer to Fareham than to Winchester...

, Hampshire, England, where they can be viewed to this day.

Almost from her beginnings, Chesapeake was considered an "unlucky ship", the "runt of the litter" to the superstitious sailors of the 19th century, and the product of a disagreement between Humphreys and Fox. Her ill-fated encounters with HMS Leopard and Shannon, the court martials of two of her captains, and the accidental deaths of several crewmen led many to believe she was cursed.

Arguments defending both Humphreys and Fox regarding their long-standing disagreements over the design of the frigates carried on for years. Humphreys disowned any credit for Fox's redesign of Chesapeake. In 1827 he wrote, "She [Chesapeake] spoke his [Fox's] talents. Which I leave the Commanders of that ship to estimate by her qualifications."

Lawrence's last command of "Don't give up the ship!" became a rallying cry for the US Navy. Oliver Hazard Perry

Oliver Hazard Perry

United States Navy Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry was born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island , the son of USN Captain Christopher Raymond Perry and Sarah Wallace Alexander, a direct descendant of William Wallace...

, in command of naval forces on Lake Erie during September 1813, named his flagship

Flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, reflecting the custom of its commander, characteristically a flag officer, flying a distinguishing flag...

, which flew a broad blue flag bearing the words " give up the ship!" The phrase is still used in the US Navy today, as displayed on the .

Chesapeakes blood-stained and bullet-ridden American flag was sold at auction in London in 1908. Purchased by William Waldorf Astor

William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor

William Waldorf Astor, 1st Viscount Astor was a very wealthy American who became a British nobleman. He was a member of the prominent Astor family.-Life in United States:...

, it now resides in the National Maritime Museum

National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England is the leading maritime museum of the United Kingdom and may be the largest museum of its kind in the world. The historic buildings forming part of the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site, it also incorporates the Royal Observatory, Greenwich,...

in Greenwich

Greenwich

Greenwich is a district of south London, England, located in the London Borough of Greenwich.Greenwich is best known for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich Meridian and Greenwich Mean Time...

, England, along with her signal book. The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic

Maritime Museum of the Atlantic

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic is a Canadian maritime museum located in downtown Halifax, Nova Scotia.The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic is a member institution of the Nova Scotia Museum and is the oldest and largest maritime museum in Canada with a collection of over 30,000 artifacts...

in Halifax, Nova Scotia, holds several artifacts of the battle with Shannon. In 1996 a timber fragment from the Chesapeake Mill was returned to the United States. It is on display at the Hampton Roads Naval Museum

Hampton Roads Naval Museum

The Hampton Roads Naval Museum is one of the 12 Navy museums that are operated by the Naval History & Heritage Command. It celebrates the long history of the U.S. Navy in the Hampton Roads region of Virginia. It is co-located with the Nauticus National Maritime Center in downtown Norfolk, Virginia...

.