Timeline of the development of tectonophysics

Encyclopedia

The evolution of tectonophysics

is closely linked to the history of the continental drift

and plate tectonics

hypotheses

. The continental drift hypothesis had many flaws and scarce data. The fixist, the contracting Earth and the expanding Earth concepts had many flaws as well. Wegener

had data for assuming that the relative positions of the continents change over time. It was a mistake to state the continents "plowed" through the sea. He was an outsider with a doctorate

in astronomy attacking a established theory between geophysicists. The geophysicists were right to state that the Earth is solid, and the mantle is elastic (for seismic waves) and inhomogeneous, and the ocean floor would not allow the movement of the continents. But excluding one alternative, substantiates the opposite alternative: passive continents and an active seafloor spreading and subduction

, with accretion

belts on the edges of the continents. The velocity of the sliding continents, was allowed in the uncertainty of the fixed continent model and seafloor subduction and upwelling with phase change allows for inhomogeneity.

The problem too, was the specialisation. A. Holmes

and A. Rittmann

saw it right . Only an outsider can have the overview, only an outsider sees the forest, not only the trees . But A. Wegener did not have the specialisation to correctly weight the quality of the geophysical data and the paleontologic data, and its conclusions. Wegener's main interest was meteorology, and he wanted to join the Denmark-Greenland expedition scheduled for mid 1912. So he hurried up to present his Continental Drift hypothesis.

}

}

}

}

}

.png)

}

}

}

Actually, there were two main "schools of thought" that pushed plate tectonics

forward:

Wegener's continental drift hypotheses is a logical consequence of: the theory of thrusting (alpine geology), the isostasy, the continents forms resulting from the supercontinent Gondwana break up, the past and present-day life forms on both sides of the Gondwana continent margins, and the Permo-Carboniferous moraine deposits in South Gondwana.

Tectonophysics

Tectonophysics, a branch of geophysics, is the study of the physical processes that underlie tectonic deformation. The field encompasses the spatial patterns of stress, strain, and differing rheologies in the lithosphere and asthenosphere of the Earth; and the relationships between these patterns...

is closely linked to the history of the continental drift

Continental drift

Continental drift is the movement of the Earth's continents relative to each other. The hypothesis that continents 'drift' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596 and was fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912...

and plate tectonics

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

hypotheses

Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. The term derives from the Greek, ὑποτιθέναι – hypotithenai meaning "to put under" or "to suppose". For a hypothesis to be put forward as a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it...

. The continental drift hypothesis had many flaws and scarce data. The fixist, the contracting Earth and the expanding Earth concepts had many flaws as well. Wegener

Alfred Wegener

Alfred Lothar Wegener was a German scientist, geophysicist, and meteorologist.He is most notable for his theory of continental drift , proposed in 1912, which hypothesized that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth...

had data for assuming that the relative positions of the continents change over time. It was a mistake to state the continents "plowed" through the sea. He was an outsider with a doctorate

Ph.D.

A Ph.D. is a Doctor of Philosophy, an academic degree.Ph.D. may also refer to:* Ph.D. , a 1980s British group*Piled Higher and Deeper, a web comic strip*PhD: Phantasy Degree, a Korean comic series* PhD Docbook renderer, an XML renderer...

in astronomy attacking a established theory between geophysicists. The geophysicists were right to state that the Earth is solid, and the mantle is elastic (for seismic waves) and inhomogeneous, and the ocean floor would not allow the movement of the continents. But excluding one alternative, substantiates the opposite alternative: passive continents and an active seafloor spreading and subduction

Subduction

In geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

, with accretion

Accretion (geology)

Accretion is a process by which material is added to a tectonic plate or a landmass. This material may be sediment, volcanic arcs, seamounts or other igneous features.-Description:...

belts on the edges of the continents. The velocity of the sliding continents, was allowed in the uncertainty of the fixed continent model and seafloor subduction and upwelling with phase change allows for inhomogeneity.

The problem too, was the specialisation. A. Holmes

Arthur Holmes

Arthur Holmes was a British geologist. As a child he lived in Low Fell, Gateshead and attended the Gateshead Higher Grade School .-Age of the earth:...

and A. Rittmann

Alfred Rittmann

Alfred Rittmann was a world's leading volcanologist at his time. His book "Vulkane und ihre Tätigkeit" was translated in five languages and it was a standard work on volcanism. He drew the right conclusion that orogenic uplift volcanism , lacks alkaline basalts...

saw it right . Only an outsider can have the overview, only an outsider sees the forest, not only the trees . But A. Wegener did not have the specialisation to correctly weight the quality of the geophysical data and the paleontologic data, and its conclusions. Wegener's main interest was meteorology, and he wanted to join the Denmark-Greenland expedition scheduled for mid 1912. So he hurried up to present his Continental Drift hypothesis.

Introduction

- Abraham OrteliusAbraham Orteliusthumb|250px|Abraham Ortelius by [[Peter Paul Rubens]]Abraham Ortelius thumb|250px|Abraham Ortelius by [[Peter Paul Rubens]]Abraham Ortelius (Abraham Ortels) thumb|250px|Abraham Ortelius by [[Peter Paul Rubens]]Abraham Ortelius (Abraham Ortels) (April 14, 1527 – June 28,exile in England to take...

(cited in ), Francis BaconFrancis BaconFrancis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

(cited in ), Theodor Christoph Lilienthal (1756) (cited in , and in Schmeling, 2004), Alexander von HumboldtAlexander von HumboldtFriedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander Freiherr von Humboldt was a German naturalist and explorer, and the younger brother of the Prussian minister, philosopher and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt...

(1801 and 1845) (cited in Schmeling, 2004), Antonio Snider-PellegriniAntonio Snider-PellegriniAntonio Snider-Pellegrini was a French geographer and scientist who theorized about the possibility of continental drift, anticipating Wegener's theories concerning Pangaea by several decades....

, and others had noted earlier that the shapes of continentContinentA continent is one of several very large landmasses on Earth. They are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, with seven regions commonly regarded as continents—they are : Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia.Plate tectonics is...

s on opposite sides of the Atlantic OceanAtlantic OceanThe Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

(most notably, Africa and South America) seem to fit together (see also , and ).- Note: Francis Bacon was thinking of western Africa and western South America and Theodor Lilienthal was thinking about the sunken island of AtlantisAtlantisAtlantis is a legendary island first mentioned in Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias, written about 360 BC....

and changing sea levels.

- Note: Francis Bacon was thinking of western Africa and western South America and Theodor Lilienthal was thinking about the sunken island of Atlantis

- CatastrophismCatastrophismCatastrophism is the theory that the Earth has been affected in the past by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope. The dominant paradigm of modern geology is uniformitarianism , in which slow incremental changes, such as erosion, create the Earth's appearance...

(e.g. Christian Fundamentalism, William ThomsonWilliam Thomson, 1st Baron KelvinWilliam Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin OM, GCVO, PC, PRS, PRSE, was a mathematical physicist and engineer. At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and did much to unify the emerging...

) vs. UniformitarianismUniformitarianismIn the philosophy of naturalism, the uniformitarianism assumption is that the same natural laws and processes that operate in the universe now, have always operated in the universe in the past and apply everywhere in the universe. It has included the gradualistic concept that "the present is the...

(e.g. Charles LyellCharles LyellSir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularised James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by slow-moving forces still in operation...

, Thomas Henry Huxley) .- Term coined by William WhewellWilliam WhewellWilliam Whewell was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge.-Life and career:Whewell was born in Lancaster...

. - Uniformitarism is the prevailing view in the U.S. .

- Term coined by William Whewell

- Pratt's isostasyIsostasyIsostasy is a term used in geology to refer to the state of gravitational equilibrium between the earth's lithosphere and asthenosphere such that the tectonic plates "float" at an elevation which depends on their thickness and density. This concept is invoked to explain how different topographic...

is the prevailing view :- Airy-HeiskanenVeikko Aleksanteri HeiskanenVeikko Aleksanteri Heiskanen was a famous Finnish geodesist.He is mostly known for his refinement of the theory of isostasy by George Airy and for his studies of the global geoid....

Model; where different topographic heights are accommodated by changes in crustal thickness. - PrattJohn Henry PrattJohn Henry Pratt was a British clergyman and mathematician who devised a theory of crustal balance which would become the basis for the isostasy principle.-Life:...

-HayfordJohn Fillmore Hayford- References :...

Model; where different topographic heights are accommodated by lateral changes in rock density. - Vening Meinesz, or Flexural Model; where the lithosphere acts as an elastic plate and its inherent rigidity distributes local topographic loads over a broad region by bending.

- Airy-Heiskanen

- A cooling and contracting EarthGeophysical global coolingBefore the concept of plate tectonics, global cooling was a reference to a geophysical theory by James Dwight Dana, also referred to as the contracting earth theory. It suggested that the Earth had been in a molten state, and features such as mountains formed as it cooled and shrank. As the...

is the prevailing view.- H. JeffreysHarold JeffreysSir Harold Jeffreys, FRS was a mathematician, statistician, geophysicist, and astronomer. His seminal book Theory of Probability, which first appeared in 1939, played an important role in the revival of the Bayesian view of probability.-Biography:Jeffreys was born in Fatfield, Washington, County...

was the most important contractionist , -

- H. Jeffreys

- H. Wettstein , E. SuessEduard SuessEduard Suess was a geologist who was an expert on the geography of the Alps. He is responsible for hypothesising two major former geographical features, the supercontinent Gondwana and the Tethys Ocean.Born in London to a Jewish Saxon merchant, when he was three his family relocated toPrague,...

, Bailey WillisBailey WillisBailey Willis was a geological engineer who worked for the United States Geological Survey , and lectured at two prominent American universities. He also played a key role in getting Mount Rainier designated as a national park in 1899...

and Benjamin FranklinBenjamin FranklinDr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

allow horizontal move of the Earth's crust.- .

- Quote, Benjamin Franklin (1782): "The crust of the Earth must be a shell floating on a fluid interior.... Thus the surface of the globe would be capable of being broken and distorted by the violent movements of the fluids on which it rested".

- The vertical movement of ScandinaviaScandinaviaScandinavia is a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern Europe that includes the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, characterized by their common ethno-cultural heritage and language. Modern Norway and Sweden proper are situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula,...

after the ice age is accepted (recent average uplift c. 1 cm/year). This implies a certain plasticity under the crust .- The alpine geology with its theory of thrusting (as Geosyncline hypothesisGeosynclineIn geology, geosyncline is a term still occasionally used for a subsiding linear trough that was caused by the accumulation of sedimentary rock strata deposited in a basin and subsequently compressed, deformed, and uplifted into a mountain range, with attendant volcanism and plutonism...

; today's thrust tectonicsThrust tectonicsThrust tectonics or contractional tectonics is concerned with the structures formed, and the tectonic processes associated with, the shortening and thickening of the crust or lithosphere.-Deformation styles:...

) accepted horizontal movements. cited in

- The alpine geology with its theory of thrusting (as Geosyncline hypothesis

- 1848 Arnold EscherArnold Escher von der LinthArnold Escher von der Linth was a Swiss geologist, the son of Hans Conrad Escher von der Linth ....

shows Roderick MurchisonRoderick MurchisonSir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet KCB DCL FRS FRSE FLS PRGS PBA MRIA was a Scottish geologist who first described and investigated the Silurian system.-Early life and work:...

the Glarus thrustGlarus thrustThe Glarus thrust is a major thrust fault in the Alps of eastern Switzerland. Along the thrust the Helvetic nappes were thrusted more than 100 km to the north over the external Aarmassif and Infrahelvetic complex...

at the Pass dil Segnas. But Arnold Escher does not publish it as a thrust as it contradicts the Geosyncline hypothesis. - Eduard Suess proposed Gondwanaland in 1861, as a result of the GlossopterisGlossopterisGlossopteris is the largest and best-known genus of the extinct order of seed ferns known as Glossopteridales ....

findings, but he believed that the oceans flooded the spaces currently between those lands. And he proposed the TethysParatethysThe Paratethys ocean, Paratethys sea or just Paratethys was a large shallow sea that stretched from the region north of the Alps over Central Europe to the Aral Sea in western Asia. The sea was formed during the Oxfordian epoch as an extension of the rift that formed the Central Atlantic Ocean and...

Sea in 1893. He came to the conclusion that the AlpsAlpsThe Alps is one of the great mountain range systems of Europe, stretching from Austria and Slovenia in the east through Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Germany to France in the west....

to the North were once at the bottom of an ocean . - 1884, Marcel Alexandre BertrandMarcel Alexandre BertrandMarcel Alexandre Bertrand was a French geologist who was born in Paris. He was a student at the École Polytechnique, and beginning in 1869 he attended the Ecole des Mines de Paris. Beginning in 1877 he performed geological mapping studies of Provence, Jura Mountains and the Alps...

interpretes the Glarus thrust as a thrust. - Hans Schardt demonstrates that the Prealps are allochthonous.

}

}

}

- 1907, thrust faultThrust faultA thrust fault is a type of fault, or break in the Earth's crust across which there has been relative movement, in which rocks of lower stratigraphic position are pushed up and over higher strata. They are often recognized because they place older rocks above younger...

s get established: LapworthCharles LapworthCharles Lapworth was an English geologist.-Biography:He was born at Faringdon in Berkshire and educated as a teacher at the Culham Diocesan Training College near Abingdon, Oxfordshire. He moved to the Scottish border region, where he investigated the previously little-known fossil fauna of the area...

, PeachBen PeachBenjamin Neeve Peach, FRS was a British geologist.He was born at Gorran Haven in Cornwall to Charles William Peach, an amateur British naturalist and geologist. Ben was educated at the Royal School of Mines in London and then joined the Geological Survey in 1862 as a geologist, moving to the...

and HorneJohn HorneJohn Horne was a Scottish geologist. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1900. He was a pupil of Ben Peach....

working on parts of the Moine ThrustMoine Thrust BeltThe Moine Thrust Belt is a linear geological feature in the Scottish Highlands which runs from Loch Eriboll on the north coast 190 km south-west to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye...

, ScotlandScotlandScotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

.

}

}

-

- Director-Generals of the British Geological Survey: Roderick MurchisonRoderick MurchisonSir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet KCB DCL FRS FRSE FLS PRGS PBA MRIA was a Scottish geologist who first described and investigated the Silurian system.-Early life and work:...

(1855–1872) and Archibald GeikieArchibald GeikieSir Archibald Geikie, OM, KCB, PRS, FRSE , was a Scottish geologist and writer.-Early life:Geikie was born in Edinburgh in 1835, the eldest son of musician and music critic James Stuart Geikie...

(1881–1901)

- Director-Generals of the British Geological Survey: Roderick Murchison

- Although Wegener's theory was formed independently and was more complete than those of his predecessors, Wegener later credited a number of past authors with similar ideas: Franklin Coxworthy (between 1848 and 1890), Roberto MantovaniRoberto MantovaniRoberto Mantovani , was an Italian geologist and violinist.Mantovani was born in Parma. His father, Timoteo, died seven months after his birth. His mother, Luigia Ferrari, directed him to studies, and at the age of 11 he was accepted as a boarder in the Royal School of Music, where he was...

(between 1889 and 1909), William Henry PickeringWilliam Henry PickeringWilliam Henry Pickering was an American astronomer, brother of Edward Charles Pickering. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1883.-Work:...

(1907) and Frank Bursley TaylorFrank Bursley TaylorFrank Bursley Taylor was an American geologist, the son of a lawyer in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He was a Harvard dropout who studied privately financed in large part by his wealthy father...

(1908).- 1912-1929: Alfred Wegener develops his continental drift hypothesis.

- In the 1920s Earth scientists refer to themselves as drifters (or mobilists) or fixists.

- Moreover, most of the blistering attacks were aimed at Wegener himself, an outsider (PhD in Astronomy) who seemed to be attacking the very foundations of geology.

Controversy

.png)

- 1912, Wegener presents his ideas at the German Geological Society, Frankfurt . Karl Erich Andrée (University of Marburg) must have delivered him some references. Strong points:

- Matching of the coastlines of eastern South America and western Africa, and many similarities between the respective coastlines of North America and Europe.

- Numerous geological similarities between Africa and South America, and others between North America and Europe.

- Many examples of past and present-day life forms having a geographically disjunctive distribution.

- Mountain ranges are usually located along the coastlines of the continents, and orogenic regions are long and narrow in shape.

- The Earth's crust exhibits two basic elevations, one corresponding to the elevation of the continental tables, the other to the ocean floors.

- The Permo-Carboniferous moraine deposits found in South Africa, Argentina, southern Brazil, India, and in western, central, and eastern Australia.

- Flooded land-bridges contradict isostasy.

- Note I: Wegener described in a sentence the seafloor spreading in the first publication only. But he believed it is a consequence of the continental drift ( in ). He abandoned this sentence probably under the advice of Emanuel KayserEmanuel KayserFriedrich Heinrich Emanuel Kayser was a German geologist and palaeontologist, born at Königsberg.He was educated at Berlin, where he took his degree of Ph.D. in 1870. In 1882, he became professor of geology in the University of Marburg...

, University of Marburg. - Note II: ‘Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen’ is one of the leading geographical monthlies of international reputation. ; Wladimir Köppen (father-in-law), , , and Kurt Wegener (brother), , , defended there the Continental drift hypothesis in a somewhat mirror controversy (in ).

- Note III: Although the climate distribution was not always similar to nowadays. In the CarboniferousCarboniferousThe Carboniferous is a geologic period and system that extends from the end of the Devonian Period, about 359.2 ± 2.5 Mya , to the beginning of the Permian Period, about 299.0 ± 0.8 Mya . The name is derived from the Latin word for coal, carbo. Carboniferous means "coal-bearing"...

, coal mines are remains of the Equatorial Realm, glaciation remains are near the South PoleSouth PoleThe South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

, and between glaciation and Equatorial Realm (centered between latitude 30° and the Tropic of CancerTropic of CancerThe Tropic of Cancer, also referred to as the Northern tropic, is the circle of latitude on the Earth that marks the most northerly position at which the Sun may appear directly overhead at its zenith...

and the CapricornTropic of CapricornThe Tropic of Capricorn, or Southern tropic, marks the most southerly latitude on the Earth at which the Sun can be directly overhead. This event occurs at the December solstice, when the southern hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun to its maximum extent.Tropic of Capricorn is one of the five...

) there are remains of desertDesertA desert is a landscape or region that receives an extremely low amount of precipitation, less than enough to support growth of most plants. Most deserts have an average annual precipitation of less than...

s (evaporiteEvaporiteEvaporite is a name for a water-soluble mineral sediment that result from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporate deposits, marine which can also be described as ocean deposits, and non-marine which are found in standing bodies of...

s, salt lakes and sand dunes) . These are consequences of the evaporation rate and the atmospheric circulationAtmospheric circulationAtmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of air, and the means by which thermal energy is distributed on the surface of the Earth....

.

- 1914, the idea of a strong outer layer (lithosphereLithosphereThe lithosphere is the rigid outermost shell of a rocky planet. On Earth, it comprises the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of thousands of years or greater.- Earth's lithosphere :...

), overlying a weak asthenosphereAsthenosphereThe asthenosphere is the highly viscous, mechanically weak and ductilely-deforming region of the upper mantle of the Earth...

is introduced . - H. Jeffreys and others, most important criticisms , :

- Continents can not "plow" through the sea, because the seafloor is denser than the continental crust.

- Pole-fleeing force is too weak to move continents and produce mountains.

- Paul Sophus EpsteinPaul Sophus EpsteinPaul Sophus Epstein was a Russian-American mathematical physicist...

calculated it to be one millionth of the gravity.

- Paul Sophus Epstein

- If the tidal force moves continents, than the Earth's rotation would stop after only one year.

- Its opening sentence is GalileoGalileo GalileiGalileo Galilei , was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations and support for Copernicanism...

's allegedly muttered rebellious phrase And yet it movesAnd Yet It MovesAnd Yet It Moves is a single-player puzzle platform game developed by independent developer Broken Rules. The game was released on personal computer and WiiWare platforms, and the name itself is an English translation of Galileo Galilei's famous remark E pur si muove!-Gameplay:And Yet It Moves is...

. - Quote: "Daly,..., seeks to substitute sliding for drifting, assuming that broad domes or bulges form at the earth's surface, and on the flanks of these domes the continental masses slide downward, moving over hot basaltic glass as over a lubricated floor". (pp. 170–291)

- By the mid-1920s, A. Holmes had rejected contractionism and he had introduced a model with convection , , , .

- Note: in a way, not only A. Wegener ( in ) but A. Holmes and K. Wegener suggested seafloor spreading as well. ( in ), ( in )

- The Alps were and still are the best investigated orogen worldwide. Otto Ampferer (Austrian Geological Survey) rejected contractionism 1906 and he defended convection, locally only at first. Otto Ampferer even used the word swallowed in a geological sense. The Geological Society Meeting in Innsbruck, held in 29 August 1912, changed a paradigm (T. Termier words, the acceptance of nappeNappeIn geology, a nappe is a large sheetlike body of rock that has been moved more than or 5 km from its original position. Nappes form during continental plate collisions, when folds are sheared so much that they fold back over on themselves and break apart. The resulting structure is a...

s and thrust faultThrust faultA thrust fault is a type of fault, or break in the Earth's crust across which there has been relative movement, in which rocks of lower stratigraphic position are pushed up and over higher strata. They are often recognized because they place older rocks above younger...

s). So that Émile ArgandÉmile ArgandÉmile Argand was a Swiss geologist.He was born in Eaux-Vives near Geneva. He attended vocational school in Geneva then worked as a draftsman...

(1916) speculated that the Alps were caused by the North motion of the African shield, and finally accepted this reason 1922, following Wegener's Continental drift theory ( as ). Otto Ampferer in the mean time, at the Geological Society Meeting in Vienna, held in 4 April 1919, defended the link between the alpine faulting and Wegener's continental drift.- Quote, translation: "The Alpine orogeny is the effect of the migration of the North African shield. Smoothing only alpine folds and nappes on the cross section between the Black Forest and Africa once again, then from the present distance of about 1,800 km, we have an initial gap of around 3,000 to 3,500 km, ie. a pressing of the alpine region, alpine region in a broader sense, of 1,500 km. To this amount must be Africa have moved to Europe. This brings us then to a true large scale continental drift of the African shield". cited in

- W.A.J.M. van Waterschoot van der Gracht, Bailey WillisBailey WillisBailey Willis was a geological engineer who worked for the United States Geological Survey , and lectured at two prominent American universities. He also played a key role in getting Mount Rainier designated as a national park in 1899...

, Rollin T. Chamberlin, John JolyJohn JolyJohn Joly FRS was an Irish physicist, famous for his development of radiotherapy in the treatment of cancer...

, G.A.F. MolengraaffGustaaf Adolf Frederik MolengraaffGustaaf Adolf Frederik Molengraaff was a Dutch geologist, biologist and explorer. He became an authority on the geology of South Africa and the Dutch East Indies....

, J.W. GregoryJohn Walter GregoryJohn Walter Gregory, FRS, was a British geologist and explorer, known principally for his work on glacial geology and on the geography and geology of Australia and East Africa.-Early life:...

, Alfred WegenerAlfred WegenerAlfred Lothar Wegener was a German scientist, geophysicist, and meteorologist.He is most notable for his theory of continental drift , proposed in 1912, which hypothesized that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth...

, Charles SchuchertCharles SchuchertCharles Schuchert was an American invertebrate paleontologist who was a leader in the development of paleogeography, the study of the distribution of lands and seas in the geological past.-Biography:...

, Chester R. Longwell, Frank Bursley TaylorFrank Bursley TaylorFrank Bursley Taylor was an American geologist, the son of a lawyer in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He was a Harvard dropout who studied privately financed in large part by his wealthy father...

, William BowieWilliam BowieWilliam Bowie, B.S., C.E., M.A. was an American geodetic engineer.-Background and education:He was born at Grassland, an historic estate near Annapolis Junction, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, to Thomas John Bowie and Susanna Anderson. He was educated in public schools, at St...

, David WhiteDavid White (geologist)David White was an American geologist, born in Palmyra, New York.He graduated from Cornell University in 1886, and in 1889 became a member of the United States Geological Survey. Eventually, he rose to be chief geologist.In 1903 he became an associate curator of paleobotany at the Smithsonian...

, Joseph T. Singewald, Jr., and Edward W. BerryEdward W. BerryEdward Wilber Berry was an American paleontologist and botanist, the principal focus of his research was paleobotany. Berry studied North and South American flora and published taxonomic studies with theoretical reconstructions of paleoecology and phytogeography. He started his scientific...

participated on a Symposium of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG, 1926) Although the chairman favored the drift hypothesis, it ceased to be an acceptable geological investigation subject in many universities under the influence of book .- Quote, University of Chicago geologist Rollin T. Chamberlin: "If we are to believe in Wegener's hypothesis we must forget everything which has been learned in the past 70 years and start all over again." ,

- Quote, Bailey Willis: "further discussion of it merely incumbers the literature and befogs the mind of fellow students. (It is) as antiquated as pre-Curie physics". ,

- Bailey Willis and William Bowie saw the simaSima (geology)Sima is the name for the lower layer of the Earth's crust. This layer is made of rocks rich in magnesium silicate minerals. Typically when the sima comes to the surface it is basalt, so sometimes this layer is called the 'basalt layer' of the crust. The sima layer is also called the 'basal crust'...

with great strength and rigidity through the seismological studies, and tidal forces would act more on the sima (2800 to 3300 kg/m3) as it is denser than the sialSialIn geology, the sial is the upper layer of the Earth's crust made of rocks rich in silicates and aluminium minerals. It is sometimes equated with the continental crust because it is absent in the wide oceanic basins, but "sial" is a geochemical term rather than a plate tectonic term.Geologists...

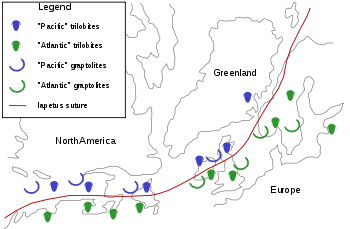

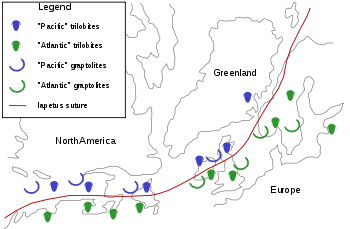

(2700 to 2800 kg/m3) . - Quote, W. Van Waterschoot van der Gracht (Wilson cycle): "there may have been a pre-Carboniferous "Atlantic" that was closed up during the Caledonian orogenis" .

- By the late-1920s: discovery of the Wadati-Benioff zone by Hugo BenioffHugo BenioffVictor Hugo Benioff was an American seismologist and a professor at the California Institute of Technology. He is best remembered for his work in charting the location of deep earthquakes in the Pacific Ocean....

of the California Institute of TechnologyCalifornia Institute of TechnologyThe California Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Pasadena, California, United States. Caltech has six academic divisions with strong emphases on science and engineering...

, and Kiyoo WadatiKiyoo WadatiProfessor was an early seismologist at the Central Meteorological Observatory of Japan, researching deep earthquakes. His name is attached to the Wadati-Benioff zone...

of the Japan Meteorological AgencyJapan Meteorological AgencyThe or JMA, is the Japanese government's weather service. Charged with gathering and reporting weather data and forecasts in Japan, it is a semi-autonomous part of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport...

. - Alexander du ToitAlexander Du ToitAlexander Logie du Toit was a geologist from South Africa, and an early supporter of Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift.Born in Newlands, Cape Town in 1878, du Toit was educated at the Diocesan College in Rondebosch and the University of the Cape of Good Hope...

's book.- In 1923, he received a grant from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and used this to travel to eastern South America to study the geology of Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil.

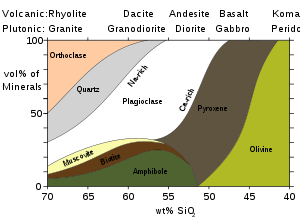

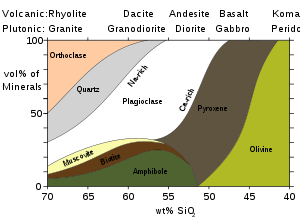

- 1931: Peacock named the calc-alkalineCalc-alkalineThe calc-alkaline magma series is one of two main magma series in igneous rocks, the other magma series being the tholeiitic. A magma series is a series of compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic magma, which is high in magnesium and iron and produces basalt or gabbro, as it...

igneous rock series. - 1936, Augusto Gansser-BiaggiAugusto Gansser-BiaggiAugusto Gansser-Biaggi is a Swiss geologist who specialised in the geology of the Himalayas. He was born in Milan.-Career:His geological researches were global in scope:* East Greenland , a 4 month expedition under Lauge Koch....

interpreted rocks located at the foot of Mount KailashMount KailashMount Kailash is a peak in the Gangdisê Mountains, which are part of the Himalayas in Tibet...

in the Indian part of the Himalayas as having originated in the seafloor. He brings back a sample with AmmoniteAmmoniteAmmonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct subclass within the Molluscan class Cephalopoda which are more closely related to living coleoids Ammonite, as a zoological or paleontological term, refers to any member of the Ammonoidea an extinct...

s of the NorianNorianThe Norian is a division of the Triassic geological period. It has the rank of an age or stage . The Norian lasted from 216.5 ± 2.0 to 203.6 ± 1.5 million years ago. It was preceded by the Carnian and succeeded by the Rhaetian.-Stratigraphic definitions:The Norian was named after the Noric Alps in...

(TriassicTriassicThe Triassic is a geologic period and system that extends from about 250 to 200 Mya . As the first period of the Mesozoic Era, the Triassic follows the Permian and is followed by the Jurassic. Both the start and end of the Triassic are marked by major extinction events...

). He later interpreted this Indus-Yarlung-Zangpo Suture ZoneIndus-Yarlung suture zoneThe Indus-Yarlung suture zone or the Indus-Yarlung Zangbo suture is a tectonic suture in southern Tibet and across the north margin of the Himalayas which resulted from the collision between the Indian plate and the Eurasian plate starting about 52 Ma. The north side of the suture zone is the...

(ISZ) as the border between the Indian and the Eurasian PlateEurasian PlateThe Eurasian Plate is a tectonic plate which includes most of the continent of Eurasia , with the notable exceptions of the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian subcontinent, and the area east of the Chersky Range in East Siberia...

. - January, 1939: at the annual meeting of the German Geological Society, Frankfurt, Alfred RittmannAlfred RittmannAlfred Rittmann was a world's leading volcanologist at his time. His book "Vulkane und ihre Tätigkeit" was translated in five languages and it was a standard work on volcanism. He drew the right conclusion that orogenic uplift volcanism , lacks alkaline basalts...

opposed the idea that the Mid-Atlantic RidgeMid-Atlantic RidgeThe Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge, a divergent tectonic plate boundary located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. It separates the Eurasian Plate and North American Plate in the North Atlantic, and the African Plate from the South...

was a orogenic uplift .- OrogenicOrogenyOrogeny refers to forces and events leading to a severe structural deformation of the Earth's crust due to the engagement of tectonic plates. Response to such engagement results in the formation of long tracts of highly deformed rock called orogens or orogenic belts...

volcanism (Pacific Ring of FirePacific Ring of FireThe Pacific Ring of Fire is an area where large numbers of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions occur in the basin of the Pacific Ocean. In a horseshoe shape, it is associated with a nearly continuous series of oceanic trenches, volcanic arcs, and volcanic belts and/or plate movements...

) is dominated by calc-alkalineCalc-alkalineThe calc-alkaline magma series is one of two main magma series in igneous rocks, the other magma series being the tholeiitic. A magma series is a series of compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic magma, which is high in magnesium and iron and produces basalt or gabbro, as it...

igneous rocks (Calc series), lacking alkali-basaltic magmas (Sodic series); whereas the Mid-Atlantic RidgeMid-Atlantic RidgeThe Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge, a divergent tectonic plate boundary located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. It separates the Eurasian Plate and North American Plate in the North Atlantic, and the African Plate from the South...

(extension) has mainly alkali-basaltic magmas . sees subduction as the cause of Wadati-Benioff zone and volcanic activity, but does not link it to continental drifting. He was in a way an anti-drifter.

- Mid-1940s, paleontologist George Gaylord SimpsonGeorge Gaylord SimpsonGeorge Gaylord Simpson was an American paleontologist. Simpson was perhaps the most influential paleontologist of the twentieth century, and a major participant in the modern evolutionary synthesis, contributing Tempo and mode in evolution , The meaning of evolution and The major features of...

finds flaws on the paleontology data. - Alexander du Toit, GlossopterisGlossopterisGlossopteris is the largest and best-known genus of the extinct order of seed ferns known as Glossopteridales ....

findings in Russia are an erroneous identification. It was used as argument by anti-drifters . - 1948, Felix Andries Vening MeineszFelix Andries Vening MeineszFelix Andries Vening Meinesz was a Dutch geophysicist and geodesist. He is known for his invention of a precise method for measuring gravity. Thanks to his invention, it became possible to measure gravity at sea, which led him to the discovery of gravity anomalies above the ocean floor...

, Dutch geophysicist who believes in convection currents as a result of his work on oceanic gravity anomalies. Highly respected by H. H. Hess, Hess even got a chance to work with him. , , , , , - 1949, Niskanen calculates the viscosity under the crust to be 5 1021 CGS units.

- 1950, fading of the hypothesis from view.

- 1951, Alfred Rittmann shows subductionSubductionIn geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

, volcanism and erosion in the mountainous regions. , figure 4, p. 293. - 1951, André Amstutz uses the word subduction.

}

}

- 1953, Adrian E. Scheidegger, anti-drifter.

- E.g.: it had been shown that floating masses on a rotating geoid would collect at the equator, and stay there. This would explain one, but only one, mountain building episode between any pair of continents; it failed to account for earlier orogenic episodes.

Making sense of the puzzle pieces

- 1953, the Great Global Rift, running along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, was discovered by Bruce Heezen (Lamont Group) (Puzzle pieces: Seismic-refraction and Sonar survey of the rifts). , , , ,

- Their world ocean floor map was published 1977. Austrian painter Heinrich BerannHeinrich C. BerannHeinrich C. Berann, the father of the modern panorama map, was born into a family of painters and sculptors in Innsbruck, Austria. He taught himself by trial and error...

worked on it. - Nowadays the seafloor maps have a better resolution by the SEASATSeasatSEASAT was the first Earth-orbiting satellite designed for remote sensing of the Earth's oceans and had on board the first spaceborne synthetic aperture radar . The mission was designed to demonstrate the feasibility of global satellite monitoring of oceanographic phenomena and to help determine...

, GeosatGeosatThe GEOSAT was a U.S. Navy Earth observation satellite, launched on March 12, 1985 into an 800 km, 108° inclination orbit, with an orbital period of 23.07 days and a 330 pass orbit. The satellite carried a radar altimeter capable of measuring the distance from the satellite to sea surface...

/ERM and ERS-1/ERM (European Remote-Sensing SatelliteEuropean Remote-Sensing SatelliteEuropean remote sensing satellite was the European Space Agency's first Earth-observing satellite. It was launched on July 17, 1991 into a Sun-synchronous polar orbit at a height of 782–785 km.-Instruments:...

/Exact Repeat Mission) missions.

- Their world ocean floor map was published 1977. Austrian painter Heinrich Berann

- 1954-1963: Alfred Rittmann was elected IAVInternational Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's InteriorThe International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior, or IAVCEI, is an association that represents the primary international focus for research in volcanology, efforts to mitigate volcanic disasters, and research into closely related disciplines, such as igneous...

President (IAV at that time) for three periods. - 1956, S. K. Runcorn becomes a drifter. ,

- Statistics by Ronald A. Fisher

- Jan Hospers work (magnetic poles and geographical poles coincide the last 23 Ma).

- Self-exciting dynamo theoryDynamo theoryIn geophysics, dynamo theory proposes a mechanism by which a celestial body such as the Earth or a star generates a magnetic field. The theory describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can maintain a magnetic field over astronomical time...

of ElsasserWalter M. ElsasserWalter Maurice Elsasser was a German-born American physicist considered a "father" of the presently accepted dynamo theory as an explanation of the Earth's magnetism. He proposed that this magnetic field resulted from electric currents induced in the fluid outer core of the Earth...

-BullardEdward BullardSir Edward "Teddy" Crisp Bullard FRS was a geophysicist who is considered, along with Maurice Ewing, to have founded the discipline of marine geophysics...

.

- S. W. CareySamuel Warren CareySamuel Warren Carey AO was an Australian geologist who was an early advocate of the theory of continental drift. His work on plate tectonics reconstructions led him to develop the Expanding Earth hypothesis.- Biography :Carey was born in New South Wales and grew up on a farm three miles from...

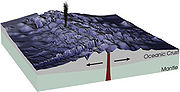

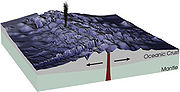

, Plate tectonics . But he believed here in a Expanding Earth. - Seafloor spreadingSeafloor spreadingSeafloor spreading is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge. Seafloor spreading helps explain continental drift in the theory of plate tectonics....

- December 1960, Harry H. HessHarry Hammond HessHarry Hammond Hess was a geologist and United States Navy officer in World War II.Considered one of the "founding fathers" of the unifying theory of plate tectonics, Rear Admiral Harry Hammond Hess was born on May 24, 1906 in New York City...

(preprint and a report for the Navy): Sonar and seafloor spreading (personal communication formally published in 1962 (Puzzle pieces: his World War II seafloor profiles, Carey (1958), Vening Meinesz (1948, oceanic gravity anomalies) and the Great Global Rift). , , , - 1961, Robert S. DietzRobert S. DietzRobert Sinclair Dietz was Professor of Geology at Arizona State University. Dietz was a marine geologist, geophysicist and oceanographer who conducted pioneering research along with Harry Hammond Hess concerning seafloor spreading, published as early as 1960–1961...

., the Permian tillite at Squantum, Massachusetts, was reclassified as turbidite. It was used as argument by anti-drifters.

- December 1960, Harry H. Hess

- P. M. S. BlakettPatrick Blackett, Baron BlackettPatrick Maynard Stuart Blackett, Baron Blackett OM CH FRS was an English experimental physicist known for his work on cloud chambers, cosmic rays, and paleomagnetism. He also made a major contribution in World War II advising on military strategy and developing Operational Research...

(1960), Blakett's former lecturer S. K. Runcorn (1962), Runcorn's former student E. IrvingEdward A. IrvingEdward A. "Ted" Irving, CM, FRSC, FRS is a geologist and emeritus scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada. His studies of paleomagnetism provided the first physical evidence of the theory of continental drift...

: Paleomagnetism.- References: , , , , , ,

- 1962, S.K. Runcorn applies the Rayleigh's theory of convectionRayleigh numberIn fluid mechanics, the Rayleigh number for a fluid is a dimensionless number associated with buoyancy driven flow...

: convection occurs if viscosity under the crust is less than 1026-1027 CGS units. - 1962, SubductionSubductionIn geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

in the Aleutian Islands, Robert R. CoatsRobert R. CoatsRobert Roy Coats was born in Toronto, Canada, and grew up in Marshalltown, Iowa and Seattle, Washington. He graduated valedictorian of his high school class in Seattle at the age of 16, and attended the University of Washington, where he received both a B.S. and M.S. degree in Geology and Mining...

(USGS).- The uncertainty of the distance between Europe an North America is too great to confirm the Continental drift hypothesis. It states wrongly that the lock-and-key form of South America and Africa is less good if the continental shelf is taken into account.

Plate tectonics

- Publication of the Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis. ,

- Frederick Vine is working under Drummond MatthewsDrummond MatthewsDrummond Hoyle Matthews FRS was a British marine geologist and geophysicist and a key contributor to the theory of plate tectonics...

, University of CambridgeUniversity of CambridgeThe University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

. - Lawrence W. Morley'sLawrence MorleyLawrence Morley, Ph.D. is a Canadian geophysicist. He is best known for his studies on the magnetic properties of ocean crust and their effect on plate tectonics.-Biography:Morley worked with Britons Fred Vine and Drummond Matthews...

independent paper was not accepted.

- Frederick Vine is working under Drummond Matthews

- John Tuzo Wilson, a former fixist/contractionist up to around 1959.

- J. T. Wilson spends much of 1965 in Cambridge and Hess joined him on the second half. Wilson develops the transform fault concept. , , , ,

- Wilson cycle, .

- Frederick Vine, applies the transform faultTransform faultA transform fault or transform boundary, also known as conservative plate boundary since these faults neither create nor destroy lithosphere, is a type of fault whose relative motion is predominantly horizontal in either sinistral or dextral direction. Furthermore, transform faults end abruptly...

concept, the Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis and the seafloor spreading concept on the Juan de Fuca RidgeJuan de Fuca RidgeThe Juan de Fuca Ridge is a tectonic spreading center located off the coasts of the state of Washington in the United States and the province of British Columbia in Canada. It runs northward from a transform boundary, the Blanco Fracture Zone, to a triple junction with the Nootka Fault and the...

. He does not get a constant spreading rate as the Jamarillo reversal (Geomagnetic reversalGeomagnetic reversalA geomagnetic reversal is a change in the Earth's magnetic field such that the positions of magnetic north and magnetic south are interchanged. The Earth's field has alternated between periods of normal polarity, in which the direction of the field was the same as the present direction, and reverse...

) is unknown. , , .

- Wells, finds on growth rings of Devonian corals the maximum Earth expansion during this time to be less than 0.6 mm/year , . Heezen, abandons the expanding Earth theory as it requires a radial expansion of 4–8 mm/year for the Atlantic Ocean alone .

- 1966, East South America and West Africa, rocks and their ages match where they were joint: South AfricaSouth AfricaThe Republic of South Africa is a country in southern Africa. Located at the southern tip of Africa, it is divided into nine provinces, with of coastline on the Atlantic and Indian oceans...

/ Santa de la Ventana, ArgentinaArgentinaArgentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

; GhanaGhanaGhana , officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country located in West Africa. It is bordered by Côte d'Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, Togo to the east, and the Gulf of Guinea to the south...

/ São Luís do Maranhão, BrazilBrazilBrazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

.- Nowadays, the fit between Africa and South America is based on paleomagnetism, slightly different to the older "Bullard's Fit" (based on least-square fitting of 500 fathom (c. 900 m) contours across the Atlantic). ,

- Closure:

- November 1965, Geological Society of America, Brent Dalrymple (Brent DalrympleBrent DalrympleG. Brent Dalrymple is an American geologist, author of The Age of the Earth and Ancient Earth, Ancient Skies, and National Medal of Science winner....

, Richard DoellRichard DoellRichard Doell was a distinguished American scientist known for developing the time scale for geomagnetic reversals with Allan V. Cox and Brent Dalrymple. This work was a major step in the development of plate tectonics...

and Allan V. CoxAllan V. CoxAllan Verne Cox was an American geophysicist. His work on dating geomagnetic reversals, with Richard Doell and Brent Dalrymple, made a major contribution to the theory of plate tectonics. Allan Cox won numerous awards, including the prestigious Vetlesen Prize, and was the president of the American...

- USGS) brought to Frederik Vine attention that there is the Jaramillo "reversal" (publ. mid-1966 !!!). , - February 1966, Vine visits the Lamont group (Walt Pitman and Neil Opdyke) and tells them that their 'discovered' Emperor reversal was already named as Jaramillo reversal. And shows the reversal on the Walt Pitman's graphik (cm/ vertical), surprising Pitman, Opdyke and even himself , . Many anti-drifters changed their mind after the publication of these magnetometer readings of sediment core (Eltanin-19), geomagnetic reversals .

- The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis is the first scientific test to confirm the seafloor spreading concept. Earth Sciences paradigm shift, from fix continents to plate tectonics :

- Magnetometer readings of sediment cores, geomagnetic reversals: ratio of cm (vertical).

- Magnetic profiles of seafloor, geomagnetic reversals: ratio of km (horizontal).

- Radiometric analysis of lava flows, geomagnetic reversals: ratio of Ma (time).

- November 1965, Geological Society of America, Brent Dalrymple (Brent Dalrymple

- Even Maurice EwingMaurice EwingWilliam Maurice "Doc" Ewing was an American geophysicist and oceanographer.Ewing has been described as a pioneering geophysicist who worked on the research of seismic reflection and refraction in ocean basins, ocean bottom photography, submarine sound transmission , deep sea coring of the ocean...

(Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory) came to accept seafloor spreading by April 1967 and cited (along with his brother John Ewing) the case for Vine-Matthews-Morley Hypothesis as "strong support for the hypothesis of spreading.

}

- Around 1967, Marshall KayMarshall KayMarshall Kay was a geologist and professor at Columbia University. He is best known for his studies of the Ordovician of New York, Newfoundland, and Nevada, but his studies were global and he published widely on the stratigraphy of the middle and upper Ordovician. Kay's careful fieldwork provided...

becomes a drifter. - In 1967, W. Jason MorganW. Jason MorganWilliam Jason Morgan is an American geophysicist who has made seminal contributions to the theory of plate tectonics and geodynamics...

proposed that the Earth's surface consists of 12 rigid plates that move relative to each other . Two months later, in 1968, Xavier Le PichonXavier Le PichonXavier Le Pichon is a French geophysicist. Among many other contributions, he is known for his comprehensive model of plate tectonics .He is professor at the Collège de France.-Biography:Le Pichon holds a doctorate in physics....

published a complete model based on 6 major plates with their relative motions . The Englishmen Dan McKenzie and Robert Parker published the quantitative principles for plate tectonicsPlate tectonicsPlate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

(Euler's rotation theoremEuler's rotation theoremIn geometry, Euler's rotation theorem states that, in three-dimensional space, any displacement of a rigid body such that a point on the rigid body remains fixed, is equivalent to a single rotation about some axis that runs through the fixed point. It also means that the composition of two...

: Individual aseismic areas move as rigid plates on the surface of a sphere, quote: "a block on a sphere can be moved to any other conceivable orientation by a single rotation about a properly chosen axis.") .- Note I: although (received 30 August 1967, revised 30 November 1967 and published 15 March 1968) was published later than (published 30 December 1967), priority belongs to Morgan. It is based on a presentation at the American Geophysical UnionAmerican Geophysical UnionThe American Geophysical Union is a nonprofit organization of geophysicists, consisting of over 50,000 members from over 135 countries. AGU's activities are focused on the organization and dissemination of scientific information in the interdisciplinary and international field of geophysics...

's 1967 meeting (title: Rises, Trenches, Great Faults, and Crustal Blocks). - Note II: W. Jason Morgan shared with Fred Vine an office in the Princeton UniversityPrinceton UniversityPrinceton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

for two years, and a scientific paper from H. W. MenardHenry William MenardHenry William Menard was an American geologist.-Life and career:He earned a B.S. and M.S. from the California Institute of Technology in 1942 and 1947, having served in the South Pacific during World War II as a photo interpreter. In 1949, he completed a Ph.D. in marine geology at Harvard University...

drifted his attention to plate tectonics. It was probably the long faults on (cited in ) and the Euler's rotation theorem that gave him the idea.

- Note I: although (received 30 August 1967, revised 30 November 1967 and published 15 March 1968) was published later than (published 30 December 1967), priority belongs to Morgan. It is based on a presentation at the American Geophysical Union

Geodynamics

- John F. DeweyJohn Frederick DeweyJohn Frederick Dewey is a British structural geologist and a strong proponent of the theory of plate tectonics, building upon the early work undertaken in the 1960s and 1970s...

applies Plate tectonics . - Plate tectonics:

- Mantle plumeMantle plumeA mantle plume is a hypothetical thermal diapir of abnormally hot rock that nucleates at the core-mantle boundary and rises through the Earth's mantle. Such plumes were invoked in 1971 to explain volcanic regions that were not thought to be explicable by the then-new theory of plate tectonics. Some...

controversy : The relationship between subducted seafloor, flood basaltFlood basaltA flood basalt or trap basalt is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that coats large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Flood basalts have occurred on continental scales in prehistory, creating great plateaus and mountain ranges...

s and continental rifting is uncovered. , , , , ,- Plume tectonicsPlume tectonicsPlume tectonics is a geophysical theory that finds its roots in the mantle doming concept which was especially popular during the 1930s, and survived throughout the seventies up till today in various forms and presentations...

: , ,

- Plume tectonics

- Slab pull force, Slab suction force (Back-arc basinBack-arc basinBack-arc basins are geologic features, submarine basins associated with island arcs and subduction zones.They are found at some convergent plate boundaries, presently concentrated in the Western Pacific ocean. Most of them result from tensional forces caused by oceanic trench rollback and the...

) and Ridge push force:- Back-arc basin , ,

- Similar to a landslide, seafloor sinks and subducts , , , ,

- Wilson cycle: slab pull/ subductionSubductionIn geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

opens a space on western South America and the sliding seafloor away from the Mid-Atlantic RidgeMid-Atlantic RidgeThe Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge, a divergent tectonic plate boundary located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. It separates the Eurasian Plate and North American Plate in the North Atlantic, and the African Plate from the South...

on eastern South America occupies the new available space. - Overview: viscous resistance, slab thickness, slab bending, trench migration and seismic coupling, slab width, slab edges and mantle return flow:

- Mantle plume

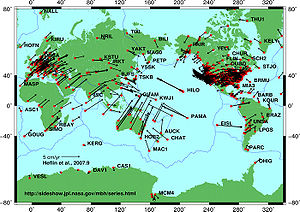

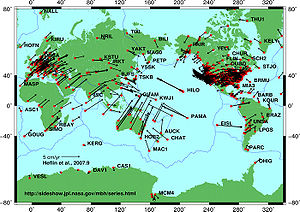

- Current plate motions. , ,

- Pacific PlatePacific PlateThe Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At 103 million square kilometres, it is the largest tectonic plate....

, lower mantleMantle (geology)The mantle is a part of a terrestrial planet or other rocky body large enough to have differentiation by density. The interior of the Earth, similar to the other terrestrial planets, is chemically divided into layers. The mantle is a highly viscous layer between the crust and the outer core....

has a greater viscosity - Tibetan PlateauTibetan PlateauThe Tibetan Plateau , also known as the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau is a vast, elevated plateau in Central Asia covering most of the Tibet Autonomous Region and Qinghai, in addition to smaller portions of western Sichuan, southwestern Gansu, and northern Yunnan in Western China and Ladakh in...

, collision generates heat ,- Total estimated radiogenic heat release (from neutrino research): 19 Terawatts

- Total directly observed heat release through Earth's surface: 31 Terawatts

- Seismic anisotropySeismic anisotropySeismic anisotropy is a term used in seismology to describe the directional dependence of seismic wavespeed in a medium within the Earth.- Crustal Anisotropy :...

, , - Plate reconstructionPlate reconstructionPlate reconstruction is the process of reconstructing the positions of tectonic plates relative to each other or to other reference frames, such as the earth's magnetic field or groups of hotspots, in the geological past...

: Torsvik, Trond Helge and Gaina, CarmenCarmen GainaCarmen Gaina is a geophysicist whose research goal is to study the evolution of the global oceanic regions, she is involved in compilation of large geophysical datasets...

, Center for Geodynamics at NGU (Geological Survey of NorwayNorwegian Geological SurveyNorwegian Geological Survey , abbr:NGU is a Norwegian government agency responsible for geologic mapping and research. The agency is located in Trondheim with an office in Tromsø, with about 225 employees...

), PGP (Physics of Geological Processes, University of Oslo, Norway); Müller, R. Dietmar, EarthByte Group, University of SydneyUniversity of SydneyThe University of Sydney is a public university located in Sydney, New South Wales. The main campus spreads across the suburbs of Camperdown and Darlington on the southwestern outskirts of the Sydney CBD. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and Oceania...

; Scotese, C.R.Christopher ScoteseChristopher R. Scotese is geologist at the University of Texas at Arlington. He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1985. He is creator of the Paleomap Project, which aims to map Earth over the last billion years, and is credited with predicting Pangaea Ultima, a possible future...

, Ziegler, A.M. and Van der Voo, R., University of Michigan, University of ChicagoUniversity of ChicagoThe University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

and University of Texas, Arlington; Ziegler, P.A.Peter ZieglerPeter Alfred Ziegler is a Swiss geologist, who made important contributions to the understanding of the geological evolution of Europe and the North Atlantic borderlands, of intraplate tectonics and of plate tectonic controls on the evolution and hydrocarbon potential of sedimentary basins...

and Stampfli, Gérard, University of BaselUniversity of BaselThe University of Basel is located in Basel, Switzerland, and is considered to be one of leading universities in the country...

and University of LausanneUniversity of LausanneThe University of Lausanne in Lausanne, Switzerland was founded in 1537 as a school of theology, before being made a university in 1890. Today about 12,000 students and 2200 researchers study and work at the university...

.- , ,

- Global plate reconstructions with velocity fields from 150 Ma to present in 10 Ma increments.

Overview

The shifting and evolution of knowledge and concepts, were from:- Eduard SuessEduard SuessEduard Suess was a geologist who was an expert on the geography of the Alps. He is responsible for hypothesising two major former geographical features, the supercontinent Gondwana and the Tethys Ocean.Born in London to a Jewish Saxon merchant, when he was three his family relocated toPrague,...

(alpine geology: theory of thrusting as a modification of the Geosyncline hypothesisGeosynclineIn geology, geosyncline is a term still occasionally used for a subsiding linear trough that was caused by the accumulation of sedimentary rock strata deposited in a basin and subsequently compressed, deformed, and uplifted into a mountain range, with attendant volcanism and plutonism...

), ; - then to Alfred WegenerAlfred WegenerAlfred Lothar Wegener was a German scientist, geophysicist, and meteorologist.He is most notable for his theory of continental drift , proposed in 1912, which hypothesized that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth...

(continental driftContinental driftContinental drift is the movement of the Earth's continents relative to each other. The hypothesis that continents 'drift' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596 and was fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912...

), , ; - then to Arthur HolmesArthur HolmesArthur Holmes was a British geologist. As a child he lived in Low Fell, Gateshead and attended the Gateshead Higher Grade School .-Age of the earth:...

(a model with convection), ; - then to Felix Andries Vening MeineszFelix Andries Vening MeineszFelix Andries Vening Meinesz was a Dutch geophysicist and geodesist. He is known for his invention of a precise method for measuring gravity. Thanks to his invention, it became possible to measure gravity at sea, which led him to the discovery of gravity anomalies above the ocean floor...

(gravity anomaliesGravity anomalyA gravity anomaly is the difference between the observed acceleration of Earth's gravity and a value predicted from a model.-Geodesy and geophysics:...

along the oceanic trenchOceanic trenchThe oceanic trenches are hemispheric-scale long but narrow topographic depressions of the sea floor. They are also the deepest parts of the ocean floor....

es implied that the crust was moving) and A. RittmannAlfred RittmannAlfred Rittmann was a world's leading volcanologist at his time. His book "Vulkane und ihre Tätigkeit" was translated in five languages and it was a standard work on volcanism. He drew the right conclusion that orogenic uplift volcanism , lacks alkaline basalts...

(subductionSubductionIn geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

), , ; - then to Samuel Warren CareySamuel Warren CareySamuel Warren Carey AO was an Australian geologist who was an early advocate of the theory of continental drift. His work on plate tectonics reconstructions led him to develop the Expanding Earth hypothesis.- Biography :Carey was born in New South Wales and grew up on a farm three miles from...

(plate tectonicsPlate tectonicsPlate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

), ; Harry Hammond HessHarry Hammond HessHarry Hammond Hess was a geologist and United States Navy officer in World War II.Considered one of the "founding fathers" of the unifying theory of plate tectonics, Rear Admiral Harry Hammond Hess was born on May 24, 1906 in New York City...

and Robert S. DietzRobert S. DietzRobert Sinclair Dietz was Professor of Geology at Arizona State University. Dietz was a marine geologist, geophysicist and oceanographer who conducted pioneering research along with Harry Hammond Hess concerning seafloor spreading, published as early as 1960–1961...

(seafloor spreadingSeafloor spreadingSeafloor spreading is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge. Seafloor spreading helps explain continental drift in the theory of plate tectonics....

), , ; - then to John Tuzo Wilson (seafloor spreading), , (transform faults), and (Wilson cycle), ;

- then to the confirmation of the Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis, and paradigm shift, and ;

- then to Jason MorganW. Jason MorganWilliam Jason Morgan is an American geophysicist who has made seminal contributions to the theory of plate tectonics and geodynamics...

, Dan McKenzie and Robert Parker (quantification of plate tectonics), , ; its uncertainty was quantified by Theodore C. Chang; - and then to computer simulation with slab pullSlab pullThe Slab pull force is a tectonic plate force due to subduction. Plate motion is partly driven by the weight of cold, dense plates sinking into the mantle at trenches. This force and the slab suction force account for most of the overall force acting on plate tectonics, and the ridge push force...

and "ridge-pushRidge-pushRidge push or sliding plate force is a proposed mechanism for plate motion in plate tectonics. Because mid-ocean ridges lie at a higher elevation than the rest of the ocean floor, gravity causes the ridge to push on the lithosphere that lies farther from the ridge.As molten magma rises at a...

" , , and with nice works published by the Scripps Institution of OceanographyScripps Institution of OceanographyScripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, is one of the oldest and largest centers for ocean and earth science research, graduate training, and public service in the world...

, the EarthByte Group (R. Dietmar Müller) and the Center for Geodynamics (Trond Helge Torsvik and Carmen GainaCarmen GainaCarmen Gaina is a geophysicist whose research goal is to study the evolution of the global oceanic regions, she is involved in compilation of large geophysical datasets...

).

Actually, there were two main "schools of thought" that pushed plate tectonics

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

forward:

- The "alternative concepts to e.g. Harold JeffreysHarold JeffreysSir Harold Jeffreys, FRS was a mathematician, statistician, geophysicist, and astronomer. His seminal book Theory of Probability, which first appeared in 1939, played an important role in the revival of the Bayesian view of probability.-Biography:Jeffreys was born in Fatfield, Washington, County...

group", James HuttonJames HuttonJames Hutton was a Scottish physician, geologist, naturalist, chemical manufacturer and experimental agriculturalist. He is considered the father of modern geology...

, Eduard SuessEduard SuessEduard Suess was a geologist who was an expert on the geography of the Alps. He is responsible for hypothesising two major former geographical features, the supercontinent Gondwana and the Tethys Ocean.Born in London to a Jewish Saxon merchant, when he was three his family relocated toPrague,...

, Alfred WegenerAlfred WegenerAlfred Lothar Wegener was a German scientist, geophysicist, and meteorologist.He is most notable for his theory of continental drift , proposed in 1912, which hypothesized that the continents were slowly drifting around the Earth...

, Alexander du ToitAlexander Du ToitAlexander Logie du Toit was a geologist from South Africa, and an early supporter of Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift.Born in Newlands, Cape Town in 1878, du Toit was educated at the Diocesan College in Rondebosch and the University of the Cape of Good Hope...

, Arthur HolmesArthur HolmesArthur Holmes was a British geologist. As a child he lived in Low Fell, Gateshead and attended the Gateshead Higher Grade School .-Age of the earth:...

and Felix Andries Vening MeineszFelix Andries Vening MeineszFelix Andries Vening Meinesz was a Dutch geophysicist and geodesist. He is known for his invention of a precise method for measuring gravity. Thanks to his invention, it became possible to measure gravity at sea, which led him to the discovery of gravity anomalies above the ocean floor...

(together with J.H.F. UmbgroveJohannes Herman Frederik UmbgroveJohannes Herman Frederik Umbgrove , called in short Jan Umbgrove, was a Dutch geologist and Earth scientist.Umbgrove studied geology at Leiden University, he finished his studies in 1926...

, B.G. EscherBerend George EscherBerend George Escher was a Dutch geologist.Escher had a broad interest, but his research was mainly on crystallography, mineralogy and volcanology. He was a pioneer in experimental geology. He was a half-brother of the artist M.C. Escher, and had some influence on his work due to his knowledge of...

and Ph.H. KuenenPhilip Henry KuenenPhilip Henry Kuenen was a Dutch geologist.Kuenen spent his earliest youth in Scotland, where his father was professor in physics. He studied geology at Leiden University, where he was a pupil of K. Martin and B.G. Escher. He finished his studies in 1925 and then became assistant to Escher...

). Holmes, Vening-Meinesz and Umbgrove had some experience in Burma or Indonesia (Pacific Ring of FirePacific Ring of FireThe Pacific Ring of Fire is an area where large numbers of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions occur in the basin of the Pacific Ocean. In a horseshoe shape, it is associated with a nearly continuous series of oceanic trenches, volcanic arcs, and volcanic belts and/or plate movements...

).- The alpine geologyGeology of the AlpsThe Alps form part of a Tertiary orogenic belt of mountain chains, called the Alpide belt, that stretches through southern Europe and Asia from the Atlantic all the way to the Himalayas. This belt of mountain chains was formed during the Alpine orogeny. A gap in these mountain chains in central...

"school of thought": , , , , and . With the theory of thrusting, nappeNappeIn geology, a nappe is a large sheetlike body of rock that has been moved more than or 5 km from its original position. Nappes form during continental plate collisions, when folds are sheared so much that they fold back over on themselves and break apart. The resulting structure is a...

s, thrust faultThrust faultA thrust fault is a type of fault, or break in the Earth's crust across which there has been relative movement, in which rocks of lower stratigraphic position are pushed up and over higher strata. They are often recognized because they place older rocks above younger...

s and subductionSubductionIn geology, subduction is the process that takes place at convergent boundaries by which one tectonic plate moves under another tectonic plate, sinking into the Earth's mantle, as the plates converge. These 3D regions of mantle downwellings are known as "Subduction Zones"...

s.

- The alpine geology

- The "Princeton University" group around H. H. Hess: Felix Andries Vening Meinesz, Harry Hammond HessHarry Hammond HessHarry Hammond Hess was a geologist and United States Navy officer in World War II.Considered one of the "founding fathers" of the unifying theory of plate tectonics, Rear Admiral Harry Hammond Hess was born on May 24, 1906 in New York City...

, John Tuzo Wilson, W. Jason MorganW. Jason MorganWilliam Jason Morgan is an American geophysicist who has made seminal contributions to the theory of plate tectonics and geodynamics...

and Frederick Vine. Overview of plate tectonics in: .- Vening-Meinesz (together with J.H.F. Umbgrove, B.G. Escher and Ph.H. Kuenen) had more evidence that the established paradigm and the reality do not match. But as all geophysicists he could not really believe in crust motions in such a large scale and he knew Wegener's Continental drift hypothesis fate too. accumulated even more evidence, but he prudently introduced them as geopoetry, quote: "Little of brilliant summary remains pertinent when confronted by the relatively small but crucial amount of information collected in the intervening years. Like Umbgrove, I shall consider this paper an essay in geopoetry."

- The IAV/ IAVEIInternational Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's InteriorThe International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior, or IAVCEI, is an association that represents the primary international focus for research in volcanology, efforts to mitigate volcanic disasters, and research into closely related disciplines, such as igneous...