Thomas Pennant

Encyclopedia

Thomas Pennant was a Welsh

naturalist

and antiquary.

The Pennants were a Welsh gentry family from the parish of Whitford, Flintshire

, who had built up a modest estate at Bychton by the seventeenth century. In 1724 Thomas' father, David Pennant, also inherited the neighbouring Downing

estate from a cousin, considerably augmenting the family's fortune. Downing Hall, where Thomas was born in the 'yellow room', became the main Pennant residence.

Pennant received his early education at Wrexham

grammar school, before moving to Thomas Croft's school in Fulham

in 1740. In 1744 he entered Queen's College, Oxford, later moving to Oriel College. Like many students from a wealthy background, he left Oxford without taking a degree, although in 1771 his work as a zoologist was recognised with an honorary degree.

At the age of twelve, Pennant later recalled, he had been inspired with a passion for natural history

through being presented with Francis Willughby

's Ornithology. A tour in Cornwall

in 1746–1747, where he met the antiquary and naturalist William Borlase

, awakened an interest in mineral

s and fossils which formed his main scientific study during the 1750s. In 1750, his account of an earthquake

at Downing was inserted in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

, where there also appeared in 1756 a paper on several coral

loid bodies he had collected at Coalbrookdale

, Shropshire

. More practically, Pennant used his geological knowledge to open a lead mine

, which helped to finance improvements at Downing after he inherited in 1763.

In 1757, at the instance of Carolus Linnaeus

, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Society of Sciences. In 1766 he published the first part of his British Zoology, a work meritorious rather as a laborious compilation than as an original contribution to science. During its progress he visited the continent and made the acquaintance of Buffon

, Voltaire

, Haller

and Pallas

.

In 1767 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society

In 1767 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society

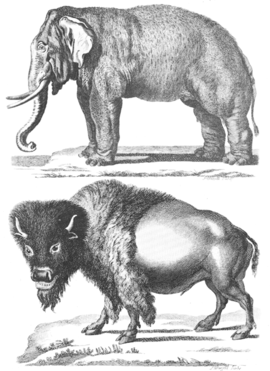

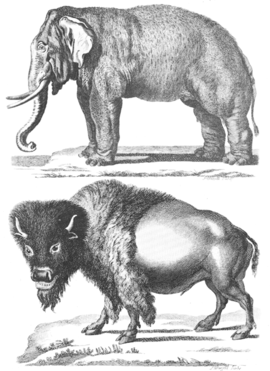

. In 1771 his Synopsis of Quadrupeds was published; it was later expanded into a History of Quadrupeds. At the end of the same year he published A Tour in Scotland in 1769, which proved remarkably popular and was followed in 1774 by an account of another journey in Scotland, in two volumes. These works have proved invaluable as preserving the record of important antiquarian relics which have now perished. In 1778 he brought out a similar Tour in Wales, which was followed by a Journey to Snowdon (part one in 1781; part two in 1783), afterwards forming the second volume of the Tour.

In 1783, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

.

In 1782 he published a Journey from Chester to London. He brought out Arctic Zoology in 1785–1787. In 1790 appeared his Account of London, which went through a large number of editions, and three years later he published the autobiographical Literary Life of the late T. Pennant. In his later years he was engaged on a work entitled Outlines of the Globe, volumes one and two of which appeared in 1798, and volumes three and four, edited by his son David Pennant, in 1800. He was also the author of a number of minor works, some of which were published posthumously. He died at Downing.

The correspondence he received from Gilbert White

was the basis for White's book The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. Unfortunately Pennant's letters to White have been lost.

Pennant's exploration of Western Isles of Scotland was revisited by Nicholas Crane

in a television documentary programme first broadcast on BBC Two

on 16 August 2007, as part of the "Great British Journeys" series. Thomas Pennant was the first in the 8 part series.

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

naturalist

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

and antiquary.

The Pennants were a Welsh gentry family from the parish of Whitford, Flintshire

Whitford, Flintshire

Whitford is a village near Holywell in Flintshire, northeast Wales.It is best known as the former home of traveller and writer Thomas Pennant.- External links :*...

, who had built up a modest estate at Bychton by the seventeenth century. In 1724 Thomas' father, David Pennant, also inherited the neighbouring Downing

Downing

- Places :* Downing Street, London, UK** 10 Downing Street, London, UK** 11 Downing Street, London, UK** 12 Downing Street, London, UK* Downing, Wisconsin, USA* Downing, Missouri, USA* Downing College, Cambridge, UK** Downing Site, Cambridge, UK...

estate from a cousin, considerably augmenting the family's fortune. Downing Hall, where Thomas was born in the 'yellow room', became the main Pennant residence.

Pennant received his early education at Wrexham

Wrexham

Wrexham is a town in Wales. It is the administrative centre of the wider Wrexham County Borough, and the largest town in North Wales, located in the east of the region. It is situated between the Welsh mountains and the lower Dee Valley close to the border with Cheshire, England...

grammar school, before moving to Thomas Croft's school in Fulham

Fulham

Fulham is an area of southwest London in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, SW6 located south west of Charing Cross. It lies on the left bank of the Thames, between Putney and Chelsea. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London...

in 1740. In 1744 he entered Queen's College, Oxford, later moving to Oriel College. Like many students from a wealthy background, he left Oxford without taking a degree, although in 1771 his work as a zoologist was recognised with an honorary degree.

At the age of twelve, Pennant later recalled, he had been inspired with a passion for natural history

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

through being presented with Francis Willughby

Francis Willughby

thumbnail|200px|right|A page from the Ornithologia, showing [[Jackdaw]], [[Chough]], [[European Magpie|Magpie]] and [[Eurasian Jay|Jay]], all [[Corvidae|crows]]....

's Ornithology. A tour in Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

in 1746–1747, where he met the antiquary and naturalist William Borlase

William Borlase

William Borlase , Cornish antiquary, geologist and naturalist, was born at Pendeen in Cornwall, of an ancient family . From 1722 he was Rector of Ludgvan and died there in 1772.-Life and works:...

, awakened an interest in mineral

Mineral

A mineral is a naturally occurring solid chemical substance formed through biogeochemical processes, having characteristic chemical composition, highly ordered atomic structure, and specific physical properties. By comparison, a rock is an aggregate of minerals and/or mineraloids and does not...

s and fossils which formed his main scientific study during the 1750s. In 1750, his account of an earthquake

Earthquake

An earthquake is the result of a sudden release of energy in the Earth's crust that creates seismic waves. The seismicity, seismism or seismic activity of an area refers to the frequency, type and size of earthquakes experienced over a period of time...

at Downing was inserted in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, where there also appeared in 1756 a paper on several coral

Coral

Corals are marine animals in class Anthozoa of phylum Cnidaria typically living in compact colonies of many identical individual "polyps". The group includes the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secrete calcium carbonate to form a hard skeleton.A coral "head" is a colony of...

loid bodies he had collected at Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. This is where iron ore was first smelted by Abraham Darby using easily mined "coking coal". The coal was drawn from drift mines in the sides...

, Shropshire

Shropshire

Shropshire is a county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. It borders Wales to the west...

. More practically, Pennant used his geological knowledge to open a lead mine

Lead

Lead is a main-group element in the carbon group with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. Lead is a soft, malleable poor metal. It is also counted as one of the heavy metals. Metallic lead has a bluish-white color after being freshly cut, but it soon tarnishes to a dull grayish color when exposed...

, which helped to finance improvements at Downing after he inherited in 1763.

In 1757, at the instance of Carolus Linnaeus

Carolus Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus , also known after his ennoblement as , was a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, who laid the foundations for the modern scheme of binomial nomenclature. He is known as the father of modern taxonomy, and is also considered one of the fathers of modern ecology...

, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Society of Sciences. In 1766 he published the first part of his British Zoology, a work meritorious rather as a laborious compilation than as an original contribution to science. During its progress he visited the continent and made the acquaintance of Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopedic author.His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Georges Cuvier...

, Voltaire

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet , better known by the pen name Voltaire , was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, free trade and separation of church and state...

, Haller

Albrecht von Haller

Albrecht von Haller was a Swiss anatomist, physiologist, naturalist and poet.-Early life:He was born of an old Swiss family at Bern. Prevented by long-continued ill-health from taking part in boyish sports, he had the more opportunity for the development of his precocious mind...

and Pallas

Peter Simon Pallas

Peter Simon Pallas was a German zoologist and botanist who worked in Russia.- Life and work :Pallas was born in Berlin, the son of Professor of Surgery Simon Pallas. He studied with private tutors and took an interest in natural history, later attending the University of Halle and the University...

.

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

. In 1771 his Synopsis of Quadrupeds was published; it was later expanded into a History of Quadrupeds. At the end of the same year he published A Tour in Scotland in 1769, which proved remarkably popular and was followed in 1774 by an account of another journey in Scotland, in two volumes. These works have proved invaluable as preserving the record of important antiquarian relics which have now perished. In 1778 he brought out a similar Tour in Wales, which was followed by a Journey to Snowdon (part one in 1781; part two in 1783), afterwards forming the second volume of the Tour.

In 1783, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

.

In 1782 he published a Journey from Chester to London. He brought out Arctic Zoology in 1785–1787. In 1790 appeared his Account of London, which went through a large number of editions, and three years later he published the autobiographical Literary Life of the late T. Pennant. In his later years he was engaged on a work entitled Outlines of the Globe, volumes one and two of which appeared in 1798, and volumes three and four, edited by his son David Pennant, in 1800. He was also the author of a number of minor works, some of which were published posthumously. He died at Downing.

The correspondence he received from Gilbert White

Gilbert White

Gilbert White FRS was a pioneering English naturalist and ornithologist.-Life:White was born in his grandfather's vicarage at Selborne in Hampshire. He was educated at the Holy Ghost School and by a private tutor in Basingstoke before going to Oriel College, Oxford...

was the basis for White's book The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. Unfortunately Pennant's letters to White have been lost.

Pennant's exploration of Western Isles of Scotland was revisited by Nicholas Crane

Nicholas Crane

Nicholas Crane is an English geographer, explorer, writer and broadcaster. Since 2004, he has written and presented four notable television series for BBC Two: Coast, Great British Journeys, Map Man and Town....

in a television documentary programme first broadcast on BBC Two

BBC Two

BBC Two is the second television channel operated by the British Broadcasting Corporation in the United Kingdom. It covers a wide range of subject matter, but tending towards more 'highbrow' programmes than the more mainstream and popular BBC One. Like the BBC's other domestic TV and radio...

on 16 August 2007, as part of the "Great British Journeys" series. Thomas Pennant was the first in the 8 part series.

External links

- Works by or about Thomas Pennant at Internet ArchiveInternet ArchiveThe Internet Archive is a non-profit digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It offers permanent storage and access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, music, moving images, and nearly 3 million public domain books. The Internet Archive...

(scanned books original editions color illustrated) - Full text of Thomas Pennant: The Journey from Chester to London (1780) on A Vision of Britain through Time, with links to the places mentioned.