The South Sea Company

Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

joint-stock company that traded in South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

during the 18th century. Founded in 1711, the company was granted a monopoly to trade in Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

's South American colonies

Spanish colonization of the Americas

Colonial expansion under the Spanish Empire was initiated by the Spanish conquistadores and developed by the Monarchy of Spain through its administrators and missionaries. The motivations for colonial expansion were trade and the spread of the Christian faith through indigenous conversions...

as part of a treaty during the War of Spanish Succession. In return, the company assumed the national debt England had incurred during the war. Speculation

Speculation

In finance, speculation is a financial action that does not promise safety of the initial investment along with the return on the principal sum...

in the company's stock led to a great economic bubble

Economic bubble

An economic bubble is "trade in high volumes at prices that are considerably at variance with intrinsic values"...

known as the South Sea Bubble in 1720, which caused financial ruin for many. In spite of this it was restructured and continued to operate for more than a century after the Bubble. The headquarters were in Threadneedle Street

Threadneedle Street

Threadneedle Street is a street in the City of London, leading from a junction with Poultry, Cornhill, King William Street and Lombard Street, to Bishopsgate....

.

Foundation

The company, established in 1711 by (among others) the Lord Treasurer Robert HarleyRobert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer KG was a British politician and statesman of the late Stuart and early Georgian periods. He began his career as a Whig, before defecting to a new Tory Ministry. Between 1711 and 1714 he served as First Lord of the Treasury, effectively Queen...

and the previous director of the Sword Blade Company John Blunt, was granted exclusive trading rights in Spanish South America. At that time, when continental America was being explored and colonized, Europeans applied the term "South Seas" only to South America and surrounding waters, not to any other ocean. The trading rights were presupposed on the successful conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was fought among several European powers, including a divided Spain, over the possible unification of the Kingdoms of Spain and France under one Bourbon monarch. As France and Spain were among the most powerful states of Europe, such a unification would have...

, which did not end until 1713, and the actual treaty-granted rights were not as comprehensive as Harley had originally hoped.

Harley needed to provide a mechanism for funding government debt

Government debt

Government debt is money owed by a central government. In the US, "government debt" may also refer to the debt of a municipal or local government...

incurred in the course of that war. However, he could not establish a bank, because the charter of the Bank of England

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694, it is the second oldest central bank in the world...

made it the only joint stock bank. He therefore established what, on its face, was a trading company, though its main activity was in fact the funding of government debt.

In return for its exclusive trading rights the government saw an opportunity for a profitable trade-off. The government and the company convinced the holders of around £10 million of short-term government debt to exchange it with a new issue of stock in the company. In exchange, the government granted the company a perpetual annuity from the government paying £576,534 annually on the company's books, or a perpetual loan of £10 million paying 6 percent. This guaranteed the new equity owners a steady stream of earnings to this new venture. The government thought it was in a win-win situation because it would fund the interest payment by placing a tariff on the goods brought from South America.

The Treaty of Utrecht

Treaty of Utrecht

The Treaty of Utrecht, which established the Peace of Utrecht, comprises a series of individual peace treaties, rather than a single document, signed by the belligerents in the War of Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht in March and April 1713...

of 1713 granted the company the right to send one trading ship per year, the Navío de Permiso (though this was in practice accompanied by two "tenders"), as well as the Asiento, the contract to supply the Spanish colonies with slaves.

Refinancing government debt

In 1717 the company took on a further £2 million of public debt; Britain's government spending being £64.4 million at the time.http://www.ukpublicspending.co.uk/budget_pie_ukgs.php?span=ukgs302&year=1717&view=1&expand=&units=b&fy=2010&state=UK#ukgs302 The rationale for the government in all these transactions was to lower interest rates on its debt. It also gave the South Sea Company (owners) a steady stream of earnings. The holder of government debt got a new investment in exchange for terminating annuities.Trading more debt for equity

In 1719 the company proposed a scheme by which it would buy more than half the national debt of Britain (£30,981,712), again with new shares, and a promise to the government that the debt would be converted to a lower interest rate, 5% until 1727 and 4% per year thereafter.The purpose of this conversion was similar to the old one: it would allow a conversion of high-interest but difficult-to-trade debt into low-interest, readily marketable debt and shares of the South Sea Company. All parties could gain.

In summary, the total government debt in 1719 was £50 million:

- £18.3m was held by three large corporations:

- £3.4m by the Bank of EnglandBank of EnglandThe Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694, it is the second oldest central bank in the world...

- £3.2m by the British East India CompanyBritish East India CompanyThe East India Company was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China...

- £11.7m by the South Sea Company

- £3.4m by the Bank of England

- Privately held redeemable debt amounted to £16.5m

- £15m consisted of irredeemable annuities, long fixed-term annuities of 72–87 years and short annuities of 22 years remaining maturity

The Bank of England proposed a similar competing offer, which did not prevail when the South Sea Company raised its bid to £7.5m (plus approximately £1.3m in bribes). The proposal was accepted in a slightly altered form in April 1720. The Chancellor of the Exchequer

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

, John Aislabie

John Aislabie

John Aislabie or Aslabie was a British politician, notable for his involvement in the South Sea Bubble and for creating the water garden at Studley Royal.-Background and education:...

, was a strong supporter of the scheme.

Crucial in this conversion was the proportion of holders of irredeemable annuities that could be tempted to convert their securities at a high price for the new shares. (Holders of redeemable debt had effectively no other choice but to subscribe.) The South Sea Company could set the conversion price but could not diverge much from the market price of its shares.

The company ultimately acquired 85% of the redeemables and 80% of the irredeemables.

Inflating the share price

The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potential trade in the New World which was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy". The share price had risen from the time the scheme was proposed: from £128 in January 1720, to £175 in February, £330 in March and, following the scheme's acceptance, to £550 at the end of May.What may have supported the company's high multiples (its P/E ratio

P/E ratio

The P/E ratio of a stock is a measure of the price paid for a share relative to the annual net income or profit earned by the firm per share...

) was a fund of credit (known to the market) of £70 million available for commercial expansion which had been made available through substantial support, apparently, by Parliament and the King.

Shares in the company were "sold" to politicians at the current market price; however, rather than paying for the shares, these recipients simply held on to what shares they had been offered, with the option of selling them back to the company when and as they chose, receiving as "profit" the increase in market price. This method, while winning over the heads of government, the King's mistress, etc., also had the advantage of binding their interests to the interests of the Company: in order to secure their own profits, they had to help drive up the stock. Meanwhile, by publicizing the names of their elite stockholders, the Company managed to clothe itself in an aura of legitimacy, which attracted and kept other buyers.

Bubble Act

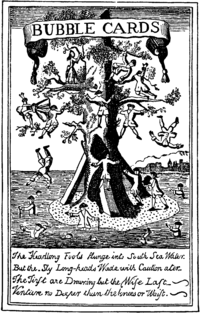

A large number of other joint-stock companies were then floated on the stock market, making extravagant claims (sometimes fraudulent) about foreign or other ventures or bizarre schemes. These were nicknamed "Bubbles".

Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal document issued by a monarch as letters patent, granting a right or power to an individual or a body corporate. They were, and are still, used to establish significant organizations such as cities or universities. Charters should be distinguished from warrants and...

. This was commonly known as the "Bubble Act". It authorised incorporation of Royal Exchange Assurance and the London Assurance Corporation, so that the short title given to the act was the Royal Exchange and London Assurance Corporation Act 1719. The prohibition on unauthorised joint stock ventures was not repealed until 1825.

The passing of the Act added a boost to the South Sea Company, its shares leaping to £890 in early June. This peak encouraged people to start to sell; to counterbalance this the company's directors ordered their agents to buy, which succeeded in propping the price up at around £750.

Top reached

The price finally reached £1,000 in early August and the level of selling was such that the price started to fall, dropping back to one hundred pounds per share before the year was out, triggering bankruptcies

Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal status of an insolvent person or an organisation, that is, one that cannot repay the debts owed to creditors. In most jurisdictions bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor....

amongst those who had bought on credit, and increasing selling, even short selling

Short selling

In finance, short selling is the practice of selling assets, usually securities, that have been borrowed from a third party with the intention of buying identical assets back at a later date to return to that third party...

—selling borrowed shares in the hope of buying them back at a profit if the price falls.

Also, in August 1720 the first of the installment payments of the first and second money subscriptions on new issues of South Sea stock were due. Earlier in the year John Blunt had come up with an idea to prop up the share price—the company would lend people money to buy its shares. As a result, many shareholders could not pay for their shares other than by selling them.

Furthermore, the scramble for liquidity appeared internationally as "bubbles" were also ending in Amsterdam

Amsterdam

Amsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

and Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. The collapse coincided with the fall of the Mississippi Scheme of John Law

John Law (economist)

John Law was a Scottish economist who believed that money was only a means of exchange that did not constitute wealth in itself and that national wealth depended on trade...

in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. As a result, the price of South Sea shares began to decline.

By the end of September the stock had fallen to £150. The company failures now extended to bank

Bank

A bank is a financial institution that serves as a financial intermediary. The term "bank" may refer to one of several related types of entities:...

s and goldsmith

Goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Since ancient times the techniques of a goldsmith have evolved very little in order to produce items of jewelry of quality standards. In modern times actual goldsmiths are rare...

s as they could not collect loans made on the stock, and thousands of individuals were ruined, including many members of the aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

. With investors outraged, Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

was recalled in December and an investigation began. Reporting in 1721, it revealed widespread fraud

Fraud

In criminal law, a fraud is an intentional deception made for personal gain or to damage another individual; the related adjective is fraudulent. The specific legal definition varies by legal jurisdiction. Fraud is a crime, and also a civil law violation...

amongst the company directors and corruption in the Cabinet. Among those implicated were John Aislabie

John Aislabie

John Aislabie or Aslabie was a British politician, notable for his involvement in the South Sea Bubble and for creating the water garden at Studley Royal.-Background and education:...

(the Chancellor of the Exchequer), James Craggs the Elder

James Craggs the Elder

James Craggs the Elder was an English politician and the father of James Craggs the Younger.A son of Anthony Craggs of Holbeck, Durham, he was baptized on 10 June 1657...

(the Postmaster General

United Kingdom Postmaster General

The Postmaster General of the United Kingdom is a defunct Cabinet-level ministerial position in HM Government. Aside from maintaining the postal system, the Telegraph Act of 1868 established the Postmaster General's right to exclusively maintain electric telegraphs...

), James Craggs the Younger

James Craggs the Younger

James Craggs the Younger , son of James Craggs the Elder, was born at Westminster. Part of his early life was spent abroad, where he made the acquaintance of George Louis, Elector of Hanover, afterwards King George I...

(the Southern Secretary

Secretary of State for the Southern Department

The Secretary of State for the Southern Department was a position in the cabinet of the government of Kingdom of Great Britain up to 1782.Before 1782, the responsibilities of the two British Secretaries of State were divided not based on the principles of modern ministerial divisions, but...

), and even Lord Stanhope

James Stanhope, 1st Earl Stanhope

James Stanhope, 1st Earl Stanhope PC was a British statesman and soldier who effectively served as Chief Minister between 1717 and 1721. He is probably best remembered for his service during War of the Spanish Succession...

and Lord Sunderland

Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland

Sir Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland KG PC , known as Lord Spencer from 1688 to 1702, was an English statesman...

(the heads of the Ministry). Craggs the Elder and Craggs the Younger both died in disgrace; the remainder were impeached for their corruption. Aislabie was imprisoned.

The newly appointed First Lord of the Treasury

First Lord of the Treasury

The First Lord of the Treasury is the head of the commission exercising the ancient office of Lord High Treasurer in the United Kingdom, and is now always also the Prime Minister...

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, KG, KB, PC , known before 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British statesman who is generally regarded as having been the first Prime Minister of Great Britain....

was forced to introduce a series of measures to restore public confidence. Under the guidance of Walpole, Parliament attempted to deal with the financial crisis. The estates of the directors of the company were confiscated and used to relieve the suffering of the victims, and the stock of the South Sea Company was divided between the Bank of England and East India Company. A resolution was proposed in parliament that bankers be tied up in sacks filled with snakes and tipped into the murky Thames. The crisis had significantly damaged the credibility of King George I

George I of Great Britain

George I was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 until his death, and ruler of the Duchy and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg in the Holy Roman Empire from 1698....

and of the Whig Party.

Quotations prompted by the collapse

Joseph Spence wrote that Lord Radnor reported to him "When Sir Isaac NewtonIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

was asked about the continuance of the rising of South Sea stock… He answered 'that he could not calculate the madness of people'." He is also quoted as stating, "I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men". Newton's niece Catherine Conduitt reported that he "lost twenty thousand pounds. Of this, however, he never much liked to hear…" This was a fortune at the time (equivalent to about £ in present day terms), but it is not clear whether it was a monetary loss or an opportunity cost

Opportunity cost

Opportunity cost is the cost of any activity measured in terms of the value of the best alternative that is not chosen . It is the sacrifice related to the second best choice available to someone, or group, who has picked among several mutually exclusive choices. The opportunity cost is also the...

loss.

A trading company

The South Seas Company's charter (of 1711) provided it with exclusive access to all of Middle and South America. However, the areas in question were Spanish colonies, and Great Britain was still at war with Spain. Even once a peace treaty had been signed, the South Sea Company was allowed to send only one ship per year to Spain’s American colonies (not one ship per colony; exactly one ship), carrying a cargo of not more than 500 tons. Additionally, it had the right to transport slaves, although steep import duties made the slave trade entirely unprofitable. Nevertheless, relations between the two countries were not good, and the company's trade suffered in two wars between Great Britain and Spain.The annual ship

The company did not undertake a trading voyage to South America until 1717 and made little actual profit. Furthermore, when ties between Spain and BritainKingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

deteriorated in 1718 the short-term prospects of the company were very poor. Nonetheless, the company continued to argue that its longer-term future would be extremely profitable.

The slave assiento

The most commercially significant aspect of the company's monopoly trading rights to the Spanish empire was the 1713 Treaty of UtrechtTreaty of Utrecht

The Treaty of Utrecht, which established the Peace of Utrecht, comprises a series of individual peace treaties, rather than a single document, signed by the belligerents in the War of Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht in March and April 1713...

's slave-trading 'Asiento

Asiento

The Asiento in the history of slavery refers to the permission given by the Spanish government to other countries to sell people as slaves to the Spanish colonies, between the years 1543 and 1834...

', which granted the exclusive right to sell slaves in all of the American colonies. The Asiento set a quota of selling 4800 people into slavery per year. Despite problems with speculation, the South Sea Company was relatively successful at slave trading and meeting its quota (it was unusual for other, similarly chartered companies to fulfill their quotas). According to records compiled by David Eltis and others, during the course of 96 voyages in twenty-five years, the South Sea Company purchased 34,000 slaves of whom 30,000 survived the voyages across the Atlantic. In other words, approximately 11% of humans transported as slaves died in transport. This was a relatively low mortality rate on the Middle Crossing

Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the triangular trade in which millions of people from Africa were shipped to the New World, as part of the Atlantic slave trade...

. The company persisted with the slave trade through two wars with Spain and the calamitous 1720 commercial bubble. The company's trade in human slavery peaked during the 1725 trading year, five years after the bubble burst.

Arctic whaling

The Greenland Company had been established by Act of Parliament in 1693 with the aim of catching whales in the Arctic. The products of their "whale-fishery" were to be free of Customs and other duties. Partly due to maritime disruption caused by wars with France, the Greenland Company failed financially within a few years. In 1722 Henry Elking published a proposal, directed at the governors of the South Sea Company, that they should resume the "Greenland Trade" and send ships to catch whales in the Arctic. He made very detailed suggestions about how the ships should be crewed and equipped.The British Parliament confirmed that a British Arctic "whale-fishery" would continue to benefit by freedom from Customs duties and in 1724 the South Sea Company decided to commence whaling. They had 12 whale-ships built on the River Thames and these went to the Greenland seas in 1725. Further ships were built in later years, but the venture was not successful. At this time there were hardly any experienced whalemen remaining in Britain and the Company had to engage Dutch and Danish whalemen for the key posts aboard their ships, e.g. all commanding officers and harpooners were hired from the North Frisia

North Frisia

North Frisia or Northern Friesland is the northernmost portion of Frisia, located primarily in Germany between the rivers Eider and Wiedau/Vidå. It includes a number of islands, e.g., Sylt, Föhr, Amrum, Nordstrand, and Heligoland.-History:...

n island of Föhr

Föhr

Föhr is one of the North Frisian Islands on the German coast of the North Sea. It is part of the Nordfriesland district in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein. Föhr is the second-largest North Sea island of Germany....

. Other costs were badly controlled and the catches remained disappointingly few, even though the Company was sending up to 25 ships to Davis Strait

Davis Strait

Davis Strait is a northern arm of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Nunavut, Canada's Baffin Island. The strait was named for the English explorer John Davis , who explored the area while seeking a Northwest Passage....

and the Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

seas in some years. By 1732 the Company had accumulated a net loss of £177,782 from their 8 years of Arctic whaling.

The South Sea Company directors appealed to the British government for further support. Parliament had passed an Act in 1732 that extended the duty-free concessions for a further 9 years. In 1733 an Act was passed that also granted a government subsidy to British Arctic whalers, the first in a long series of such Acts that continued and modified the whaling subsidies throughout the eighteenth century. This, and the subsequent Acts, required the whalers to meet conditions regarding the crewing and equipping of the whale-ships that closely resembled the conditions suggested by Elking in 1722.

In spite of the extended duty-free concessions, and the prospect of real subsidies as well, the Court and Directors of the South Sea Company decided that they could not expect to make profits from Arctic whaling. They sent out no more whale-ships after the loss-making 1732 season.

Government debt after the Bubble

The company continued its trade (when not interrupted by war) until the end of the Seven Years' WarSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War was a global military war between 1756 and 1763, involving most of the great powers of the time and affecting Europe, North America, Central America, the West African coast, India, and the Philippines...

(1756–1763). However, its main function was always managing government debt, rather than trading with the Spanish colonies. The South Sea Company continued its management of the part of the National Debt

Government debt

Government debt is money owed by a central government. In the US, "government debt" may also refer to the debt of a municipal or local government...

until it was abolished in the 1850s.

Officers of the South Sea Company

The South Sea Company had a Governor (generally an honorary position); a Subgovernor; a Deputy Governor and 30 directors (reduced in 1753 to 21).| Year | Governor | Subgovernor | Deputy Governor |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 1711 | Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford | Sir James Bateman | Samuel Ongley |

| August 1712 | Sir Ambrose Crowley Ambrose Crowley Sir Ambrose Crowley III was a 17th century English ironmonger.-Early years:He was the son of Ambrose Crowley II , a Quaker Blacksmith in Stourbridge but rose Dick Whittington-style to become Sheriff of London .-Career:... |

||

| October 1713 | Samuel Shepheard | ||

| February 1715 | George, Prince of Wales George II of Great Britain George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany... |

||

| February 1718 | King George I | ||

| November 1718 | John Fellows | ||

| February 1719 | Charles Joye | ||

| February 1721 | Sir John Eyles, Bt Sir John Eyles, 2nd Baronet Sir John Eyles, 2nd Baronet of Gidea Hall, Essex was a British financier. Eyles was the eldest surviving son of Sir Francis Eyles, 1st Baronet. He was married to his cousin, Mary Haskin Styles. Together they had two children, a girl and a boy... |

John Rudge | |

| July 1727 | King George II George II of Great Britain George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany... |

||

| February 1730 | John Hanbury John Hanbury (1664–1734) John Hanbury was one of a dynasty of ironmasters responsible for the industrialisation and urbanisation of the eastern valley through which runs the Afon Llwyd in Monmouthshire around Pontypool... |

||

| February 1733 | Sir Richard Hopkins | John Bristow | |

| February 1735 | Peter Burrell Peter Burrell Peter Burrell may refer to:*Peter Burrell , his son, British MP for Haslemere and Dover*Peter Burrell , his son, British MP for Launceston and Totnes... |

||

| March 1756 | John Bristow | John Philipson | |

| February 1756 | Lewis Way | ||

| January 1760 | King George III | ||

| February 1763 | Lewis Way | Richard Jackson | |

| March 1768 | Thomas Coventry | ||

| January 1771 | Thomas Coventry | vacant (?) | |

| January 1772 | John Warde | ||

| March 1775 | Samuel Salt | ||

| January 1793 | Benjamin Way | Robert Dorrell | |

| February 1802 | Peter Pierson | ||

| February 1808 | Charles Bosanquet Charles Bosanquet Charles Bosanquet was born at Forest House, Essex, the second son of Samuel Bosanquet and Eleanor Hunter. He married Charlotte Anne Holford on 1 June, 1796 and fathered seven children, three of whom survived him.... |

Benjamin Harrison | |

| 1820 | King George IV George IV of the United Kingdom George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later... |

||

| January 1826 | Sir Robert Baker | ||

| 1830 | King William IV William IV of the United Kingdom William IV was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death... |

||

| July 1837 | Queen Victoria Victoria of the United Kingdom Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India.... |

||

| January 1838 | Charles Franks | Thomas Vigne Thomas Vigne Thomas Vigne was an English amateur cricketer.-Career:He was mainly associated with Surrey and he made 60 known appearances in first-class matches from 1804 to 1832 . He was an occasional wicketkeeper.Vigne's son was Godfrey Vigne who played first-class cricket from 1819 to 1845.-External sources:*... |

|

See also

- United Kingdom company lawUnited Kingdom company lawUnited Kingdom company law is the body of rules that concern corporations formed under the Companies Act 2006. Also regulated by the Insolvency Act 1986, the UK Corporate Governance Code, European Union Directives and court cases, the company is the primary legal vehicle to organise and run business...

, History of company law in the United KingdomHistory of company law in the United KingdomThe history of company law in the United Kingdom concerns the change and development in UK company law within the context of the history of companies, deriving from its predecessors in Roman and English law, and the legal systems operating in the British Isles...

and History of companiesHistory of companiesThe history of companies stretches back to Roman times, and deals principally with associations of people formed to run a business, but also for charitable or leisure purposes. A corporation is one kind of company, which means an entity that has separate legal personality from the people who carry... - Atlantic slave tradeAtlantic slave tradeThe Atlantic slave trade, also known as the trans-atlantic slave trade, refers to the trade in slaves that took place across the Atlantic ocean from the sixteenth through to the nineteenth centuries...

- List of business failures

- List of stock market crashes

- Mississippi CompanyMississippi CompanyThe "Mississippi Company" became the "Company of the West" and expanded as the "Company of the Indies" .-The Banque Royale:...

- Tulip maniaTulip maniaTulip mania or tulipomania was a period in the Dutch Golden Age during which contract prices for bulbs of the recently introduced tulip reached extraordinarily high levels and then suddenly collapsed...

- C Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of CrowdsExtraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of CrowdsExtraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds is a history of popular folly by Scottish journalist Charles Mackay, first published in 1841. The book chronicles its subjects in three parts: "National Delusions", "Peculiar Follies", and "Philosophical Delusions"...

(1841)

- Hancom v Allen (1774) Dickens 498; 21 ER 363

- Trafford v Boehm (3 Atk. 440) Lord Hardwicke, where a trustee laid out trust money in the South Sea annuities, which afterwards sunk in their value; it was considered as a departure from the trust, and the trustee ordered personally to make good the deficiency to the trust-estate.

- Adie v Fennilitteau (1 Cox, 24) by the Lords Commissioners Lord Loughborough, Ashhurst, and Hotham, in April 1783, a trustee laid out trust money in South Sea annuities; they afterwards fell in their price, and though it was in the same fund in which the greatest part of the testator's personal estate was at his death invested, their Lordships held it to be an improper investment; and that the trustee should abide the loss.