Shackleton-Rowett Expedition

Encyclopedia

The Shackleton–Rowett Expedition (1921–22) was Sir Ernest Shackleton

's last Antarctic

project, and the final episode in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

. The venture, financed by businessman John Quiller Rowett

, is sometimes referred to as the Quest Expedition after its ship Quest

, a converted Norwegian sealer. Shackleton's original plan had been to explore the Beaufort Sea

sector of the Arctic Ocean

, but this was abandoned after the Canadian government withheld financial support. Quest, smaller than any recent Antarctic exploration vessel, soon proved inadequate for its task, and progress south was delayed by its poor sailing performance and by frequent engine problems. Before the expedition's work could properly begin, Shackleton died aboard ship, just after its arrival at the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia.

The major part of the subsequent attenuated expedition was a three-month cruise to the eastern Antarctic, under the leadership of second-in-command Frank Wild

. In these waters the shortcomings of Quest were soon in evidence: slow speed, heavy fuel consumption, a tendency to roll in heavy seas, and a steady leak. The ship was unable to proceed further than longitude

20°E, well short of its easterly target, and its engine's low power was insufficient for it to penetrate far into the Antarctic ice. Following several fruitless attempts to break southwards through the pack ice, Wild returned the ship to South Georgia, after a nostalgic visit to Elephant Island, where he and 21 others had been stranded after the sinking of the ship Endurance

, during Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

six years earlier.

Wild had thoughts of a second, more productive season in the ice, and took the ship to Cape Town

for a refit. Here he received a message from Rowett ordering the ship home to England, so the expedition ended quietly. Although not greatly regarded in the histories of polar exploration, the Quest voyage's significance is its standing at the very end of the Heroic Age and the beginning of the "Mechanical Age" that followed. Ultimately, however, the event that defined it in public memory, and overshadowed all its activities, was Shackleton's untimely death.

was raging. Too old to enlist, he nevertheless sought an active role in the war effort, and eventually departed for Murmansk

with the temporary army rank of major

, as part of a military mission to North Russia. This role was not satisfying to Shackleton, and he expressed his dissatisfaction in letters home: "I feel I am no use to anyone unless I am outfacing the storm in wild lands." He returned to England in February 1919 and began plans to set up a company that would, with the cooperation of the North Russian Government

, develop the natural resources of the region. This scheme came to nothing, as the Red Army

took control of that part of Russia during the Russian Civil War

, and Shackleton was forced to rely on the lecture circuit to provide him with an income. At the Philharmonic Hall in Great Portland Street

, London, during the winter of 1919–20, he lectured twice a day, six days a week, for five months. At the same time, despite the large debts still outstanding from the Endurance expedition, he began planning a new exploration venture.

Shackleton had decided to turn away from the Antarctic, go northwards, and "fill in this great blank now called the Beaufort Sea

Shackleton had decided to turn away from the Antarctic, go northwards, and "fill in this great blank now called the Beaufort Sea

". This area of the Arctic ocean, to the north of Alaska

and west of the Canadian Arctic archipelago

, was largely unexplored; Shackleton believed, on the basis of tidal records, that the sea held large undiscovered land masses that "would be of the greatest scientific interest to the world, apart from the possible economic value". He also hoped to reach the northern "pole of inaccessibility", the most remote point in the Arctic regions. In March 1920, his plans received the general approval of the Royal Geographical Society

(RGS) and were supported by the Canadian government. On this basis Shackleton set about acquiring the necessary funding, which he estimated at £50,000 (about £1.6 million, 2008 value). Later that year, Shackleton met by chance an old school-friend, John Quiller Rowett

, who agreed to put up a nucleus of cash to enable Shackleton to get started. With this money Shackleton was able, in January 1921, to acquire the wooden Norwegian whaler Foca I, and to proceed with the purchase of other equipment and the hiring of a crew.

In May 1921 the Canadian plans were abandoned. The policy of the government of Canada on the funding of expeditions changed with the advent of a new Prime Minister, Arthur Meighen

, who withdrew support from Shackleton's proposal . Shackleton's response was not to cancel the expedition but to reorient it. In the middle of May his associate Alexander Macklin

, who was in Canada negotiating the purchase of dogs, received a telegram notifying him that the destination was now to be the Antarctic; a varied programme of exploration, coastal mapping, mineral prospecting and oceanographic research in southern waters had been substituted for the Beaufort Sea venture.

, as early as March 1920 Shackleton had talked about two possible schemes—the Beaufort Sea exploration and "an oceanographical expedition with the object of visiting all the little-known islands of the South Atlantic and South Pacific". By June 1921, it had expanded to include a circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent and the mapping of around 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of uncharted coastline. It would also encompass a search for "lost" or wrongly charted sub-Antarctic islands (including Dougherty Island, Tuanaki

, and the Nimrod Islands

), investigations of possible mineral resources to be exploited in these rediscovered lands, and an ambitious scientific research program. This was to include soundings around Gough Island

to investigate an alleged "underwater continental connection between Africa and America." Shackleton biographer Margery Fisher calls the plan "diffuse", and "far too comprehensive for one small body of men to tackle within two years". According to biographer Roland Huntford

the expedition had no obvious goal and was "only too clearly a piece of improvisation, a pretext [for Shackleton] to get away".

Fisher describes the expedition as representing "the dividing line between what has become known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration and the Mechanical Age". Shackleton called the voyage "pioneering", referring specifically to the aeroplane that was taken (but ultimately not used) on the expedition. In fact this was only one of the technological "firsts" that marked the venture; there were gadgets in profusion. The ship's crow's nest

Fisher describes the expedition as representing "the dividing line between what has become known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration and the Mechanical Age". Shackleton called the voyage "pioneering", referring specifically to the aeroplane that was taken (but ultimately not used) on the expedition. In fact this was only one of the technological "firsts" that marked the venture; there were gadgets in profusion. The ship's crow's nest

was electrically heated; there were heated overalls for the lookouts, a wireless set, and a device called an odograph which could trace and chart the ship's route automatically. Photography was to figure prominently, and "a large and expensive outfit of cameras, cinematographical machines and general photographic appliances [was] acquired". Among the oceanographical research equipment was a Lucas deep-sea sounding machine.

This ample provision arose from the sponsorship of Rowett, who had extended his original gift of seed money

to an undertaking to cover the costs of the entire expedition. The extent of Rowett's contribution is not recorded; in an (undated) prospectus for the southern expedition Shackleton had estimated the total cost as "about £100,000". Whatever the total, Rowett appears to have funded the lion's share, enabling Frank Wild to record later that, unique among Antarctic expeditions of the era, this one returned home without any outstanding debt. According to Wild, without Rowett's actions the expedition would have been impossible: "His generous attitude is the more remarkable in that he knew there was no prospect of financial return, and what he did was in the interest of scientific research and from friendship with Shackleton." His only recognition was the attachment of his name to the title of the expedition. Rowett was, according to Huntford, "a stodgy, prosaic looking" businessman, who was, in 1920, a co-founder and principal contributor to an animal nutrition research institute in Aberdeen

known as the Rowett Research Institute

(now part of the University of Aberdeen

). He had also endowed dental research work at the Middlesex Hospital

. Rowett did not live long after the return of the expedition; in 1924, aged 50, he took his own life following an apparent downturn in his business fortunes.

In March 1921, Shackleton renamed his expedition vessel Quest. She was a small ship, 125 tons according to Huntford, with sail and auxiliary engine power purportedly capable of making eight knots, but in fact rarely making more than five-and-a-half. Huntford describes her as "straight-stemmed"

In March 1921, Shackleton renamed his expedition vessel Quest. She was a small ship, 125 tons according to Huntford, with sail and auxiliary engine power purportedly capable of making eight knots, but in fact rarely making more than five-and-a-half. Huntford describes her as "straight-stemmed"

, with an awkward square rig

, and a tendency to wallow in heavy seas. Fisher reports that she was built in 1917, weighed 204 tons, and had a large and spacious deck. Although she had some modern facilities, such as electric lights in the cabins, she was unsuited to long oceanic voyages; Shackleton, on the first day out, observed that "in no way are we shipshape or fitted to ignore even the mildest storm". Leif Mills, in his biography of Frank Wild

, says that had the ship been taken to the Beaufort Sea in accordance with Shackleton's original plans, she would probably have been crushed in the Arctic pack ice. On her voyage south she suffered frequent damage and breakdowns, requiring repairs at every port of call.

newspaper had reported that Shackleton planned to take a dozen men to the Arctic, "chiefly those who had accompanied him on earlier expeditions". In actuality, Quest left London for the south with 20 men, of whom eight were old Endurance comrades; another, James Dell, was a veteran from the Discovery, 20 years previously. Some of the Endurance hands had not been fully paid from the earlier expedition, but were prepared to join Shackleton again out of personal loyalty.

Frank Wild, on his fourth trip with Shackleton, filled the second-in-command post as he had on the Endurance expedition. Frank Worsley

Frank Wild, on his fourth trip with Shackleton, filled the second-in-command post as he had on the Endurance expedition. Frank Worsley

, Endurances former captain, became captain of Quest. Other old comrades included the two surgeons, Alexander Macklin

and James McIlroy, the meteorologist Leonard Hussey

, the engineer Alfred Kerr, seaman Tom McLeod and cook Charles Green. Shackleton had assumed that Tom Crean would sign up, and had assigned him duties "in charge of boats", but Crean had retired from the navy to start a family back home in County Kerry

, and declined Shackleton's invitation.

Of the newcomers, Roderick Carr

, a New Zealand-born Royal Air Force

pilot, was hired to fly the expedition's aeroplane, an Avro "Antarctic" Baby: an Avro Baby

modified as a seaplane with an 80-horse power engine. He had met Shackleton in North Russia, and had recently been serving as Chief of Staff to the Lithuania

n air force. In fact, the aeroplane was not used during the expedition due to some missing parts, and Carr therefore assisted with the scientific work. The scientific staff included Australian biologist

Hubert Wilkins, who had Arctic experience, and the Canadian geologist

Vibert Douglas, who had initially signed for the aborted Beaufort Sea expedition. The recruits who caught the most public attention were two members of the Boy Scouts' movement, Norman Mooney and James Marr. As the result of publicity organised by the Daily Mail

newspaper, these two had been selected to join the expedition out of around 1,700 Scouts who had applied to go. Mooney, who was from the Orkney Islands

, soon dropped out, leaving the ship at Madeira

after suffering chronic seasickness. Marr, an 18-year-old from Aberdeen

, remained with the expedition throughout, winning plaudits from Shackleton and Wild for his application to the tasks at hand. After being put to work in the ship's coal bunkers, according to Wild, Marr "came out of the trial very well, showing an amount of hardihood and endurance that was remarkable".

Quest sailed from St Katherine's Dock, London, on 17 September 1921, after inspection by King George V

Quest sailed from St Katherine's Dock, London, on 17 September 1921, after inspection by King George V

. Large crowds gathered on the banks of the river and on the bridges, to witness the event. Marr wrote in his diary that it was as though "all London had conspired together to bid us a heartening farewell".

Shackleton's original intention was to sail down to Cape Town

, visiting the main South Atlantic islands on the way. From Cape Town, Quest would head for the Enderby Land

coast of Antarctica where, once in the ice, it would explore the coastline in the direction of Coats Land

in the Weddell Sea

. At the end of the summer season the ship would visit South Georgia before returning to Cape Town for refitting and preparation for the second year's work. However, the ship's performance in the early stages of the voyage disrupted this schedule. Serious problems with the engine necessitated a week's stay in Lisbon

, and further stops in Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands. These delays and the slow speed of the ship led Shackleton to decide that it would be necessary to sacrifice entirely the visits to the South Atlantic islands, and instead he turned the ship towards Rio de Janeiro

, where the engine could receive a thorough overhaul. Quest reached Rio on 22 November 1921.

The engine overhaul, and the replacement of the damaged topmast, delayed the party in Rio for four weeks. This meant that it was no longer practical to proceed to Cape Town and then on to the ice. Instead, Shackleton decided that the ship would sail directly to Grytviken

harbour in South Georgia. Equipment and stores that had been sent on to Cape Town would have to be sacrificed, but Shackleton evidently hoped that this shortfall could be made up in South Georgia. He was vague about the direction the expedition should take after South Georgia; Macklin wrote in his diary, "The Boss says...quite frankly that he does not know what he will do."

After visiting the whaling establishment ashore, Shackleton returned to the ship apparently refreshed. He told Frank Wild that they would celebrate their deferred Christmas the next day, and retired to his cabin to write his diary. "The old smell of dead whale permeates everything", he wrote. "It is a strange and curious place....A wonderful evening. In the darkening twilight I saw a lone star hover, gem like above the bay." Later he slept, and was heard snoring by the surgeon McIlroy, who had just finished his watch-keeping duty. Shortly after 2 a.m. on the morning of 5 January, Macklin, who had taken over the watch, was summoned to Shackleton's cabin. According to Macklin's diary, he found Shackleton complaining of back pains and severe facial neuralgia, and asking for a painkilling drug. In a brief discussion, Macklin told his leader that he had been overdoing things, and needed to lead a more regular life. Macklin records Shackleton as saying: "You're always wanting me to give up things, what is it I ought to give up?" Macklin replied "Chiefly alcohol, Boss, I don't think it agrees with you." Immediately afterwards Shackleton "had a very severe paroxysm, during which he died".

The death certificate, signed by Macklin, gave the cause as "Atheroma of the Coronary arteries and Heart failure"—in modern terms, coronary thrombosis

. Later that morning Wild, now in command, gave the news to the shocked crew, and told them that the expedition would carry on. The body was brought ashore for embalming before its return to England. On 19 January, Leonard Hussey accompanied the body aboard a steamer bound for Montevideo

, but on arrival there he found a message from Lady Shackleton, requesting that the body be returned to South Georgia for burial. Hussey accompanied the body aboard a British steamer, and returned to Grytviken. Here, on 5 March, Shackleton was buried in the Norwegian cemetery; Quest had meantime sailed, so only Hussey of Shackleton's former comrades was present. A rough cross marked the grave, until it was replaced by a tall granite column six years later.

and then beyond, before turning south to enter the ice as close as possible to Enderby Land, and begin coastal survey work there. The expedition would also investigate an "Appearance of Land"

in the mouth of the Weddell Sea, reported by Sir James Clark Ross in 1842, but not seen since. Ultimately, however, progress would depend on weather, ice conditions, and the capabilities of the ship.

Quest left South Georgia on 18 January, heading south-east towards the South Sandwich Islands. There was a heavy swell

, such that the overladen ship frequently dipped its gunwales below the waves, filling the waist with water. As they proceeded, Wild wrote that Quest rolled like a log, was leaking and required regular pumping, was heavy on coal consumption, and was slow. All these factors led him, at the end of January, to change his plan. Bouvet Island was abandoned in favour of a more southerly course that brought them to the edge of the pack ice on 4 February.

"Now the little Quest can really try her mettle", wrote Wild, as the ship entered the loose pack. He noted that Quest was the smallest ship ever to attempt to penetrate the heavy Antarctic ice, and pondered on the fate of others. "Shall we escape, or will the Quest join the ships in Davy Jones's Locker?" During the days that followed, as they moved southward in falling temperatures, the ice thickened. On 12 February they reached the most southerly latitude they would attain, 69°17'S, and their most easterly longitude, 17°9'E, well short of Enderby Land. Noting the state of the sea ice and fearing being frozen in, Wild "beat a hasty and energetic retreat" to the north and west. Wild still hoped to tackle the heavy ice, and if possible to break through to the hidden land beyond. On 18 February he turned the ship south again for another try, but was no more successful than before. On 24 February, after a series of further efforts had failed, Wild set a course westward across the mouth of the Weddell Sea. The ship would try to visit Elephant Island in the South Shetlands

, before returning to South Georgia on the onset of winter.

For the most part, the long passage across the Weddell Sea proceeded uneventfully. Wild and Worsley were not hitting it off, according to Macklin, and there was other discontent among the crew which Wild, in his own account, dealt with by the threat of "the most drastic treatment". On 12 March they reached 64°11'S, 46°4'W, which was the area where Ross had recorded an "Appearance of Land" in 1842, but there was no sign of it, and a depth sounding of over 2,300 fathoms (13,800 ft, 4,200 m.) indicated no likelihood of land nearby. Between 15–21 March Quest was frozen into the ice, and the shortage of coal became a major concern. When the ship broke free, Wild set a course directly for Elephant Island, where he hoped that the coal supply could be supplemented by blubber

from the elephant seal

s there. On 25 March the island was sighted. Wild wanted if possible to revisit Cape Wild, the site of the old Endurance expedition camp, but bad weather prevented this. They viewed the site through binoculars, picking out the old landmarks, before landing on the western coast to hunt for elephant seals. They were able to obtain sufficient blubber to mix with the coal so that, with a favourable wind, they managed to reach South Georgia on 6 April.

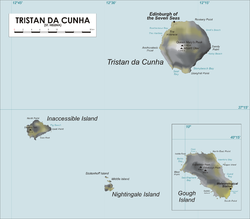

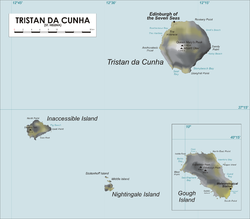

Quest remained in South Georgia for a month, during which time Shackleton's old comrades erected a memorial cairn to their former leader, on a headland overlooking the entrance to Grytviken harbor. Quest finally sailed for South Africa on 8 May. The first port of call, however, was to be Tristan da Cunha

Quest remained in South Georgia for a month, during which time Shackleton's old comrades erected a memorial cairn to their former leader, on a headland overlooking the entrance to Grytviken harbor. Quest finally sailed for South Africa on 8 May. The first port of call, however, was to be Tristan da Cunha

, a remote inhabited island to the west and south of Cape Town. Here, on the orders of the Chief Scout

, Marr was to present a flag to the local Scout Troop. After a rough crossing of the "Roaring Forties

", Quest arrived at Tristan da Cunha on 20 May.

During the five-day stay, with the help of some of the islanders, the expedition made brief landings on the small Inaccessible Island, 20 miles (32.2 km) south-west of Tristan, and visited the even smaller Nightingale Island

, collecting specimens. Wild's impressions of the stay at Tristan were not altogether favourable. He noted the appalling squalor and poverty, and said of the population: "They are ignorant, shut off almost completely from the world, horribly limited in outlook." Despite these reservations, the Scout parade and flag presentation took place before Quest sailed on to Gough Island

, 200 miles (321.9 km) to the east. Here members of the expedition took geological and botanical samples. They arrived at Cape Town on 18 June, to be greeted by enthusiastic crowds. The South African Prime Minister, Jan Smuts

, gave a official reception for them, and they were honoured at dinners and lunches by local organisations.

They were also met by Rowett's agent, with the message that they should return to England. Wild wrote: "I should have liked one more season in the Enderby Quadrant...much might be accomplished by making Cape Town our starting point and setting out early in the season." However, on 19 July they left Cape Town and sailed northwards. Their final visits were to St Helena, Ascension Island

and St Vincent

. On 16 September, one year after departure, they arrived at Plymouth Harbour

.

The lack of a clear, defined expedition objective was aggravated by the failure to call at Cape Town on the way south, with the result that important equipment was not picked up. On South Georgia, Wild found little that could make up for this loss—there were no dogs on the island, so no sledging work could be carried out, which eliminated Wild's preferred choice of a revised expedition goal, an exploration of Graham Land

on the Antarctic peninsula

. The death of Shackleton before the beginning of serious work was a heavy blow, and questions were raised about the adequacy of Wild as his replacement. Some reports have Wild drinking heavily—"practically an alcoholic", according to Shackleton's biographer, Roland Huntford

. Mills suggests, however, that even if Shackleton had lived to complete the expedition, it is arguable whether, under the circumstances, it could have achieved more than it did under Wild's command. On the voyage south, colleagues had been struck by the changes in Shackleton—his listlessness, docility and vacillation.

As for technical innovation, the failure of the aeroplane to fly was another disappointment. Shackleton's hopes had been high that he could pioneer the use of this form of transport in Antarctic waters, and he had discussed this issue with the British Air Ministry

. According to Fisher's account, essential aeroplane parts had been sent on to Cape Town, but remained uncollected. The long-range, 220-volt wireless equipment did not work properly and was abandoned early on. The smaller, 110-volt equipment worked only within a range of 250 miles (402.3 km). During the Tristan visit, Wild attempted to install a new wireless apparatus with the help of a local missionary, but this was also unsuccessful.

At the end of his narrative of the Quest expedition, Wild wrote of the Antarctic: "I think that my work there is done"; he never returned, closing a career which, like Shackleton's, had bracketed the Heroic Age. None of the expedition members who were veterans from the Endurance returned to the Antarctic, although Worsley made one voyage to the Arctic in 1925. Of the other crew and staff of Quest, the Australian naturalist Hubert Wilkins

became a pioneer aviator in both the Arctic and Antarctic, in 1928 flying from Point Barrow

, Alaska to Spitsbergen

. He also made several unsuccessful attempts during the 1930s, in collaboration with the American adventurer Lincoln Ellsworth

, to fly to the South Pole. James Marr, the Boy Scout, also became an Antarctic regular after qualifying as a marine biologist, joining several Australian expeditions in the late 1920s and 1930s. Roderick Carr, the frustrated pilot, became an Air Marshal

in the Royal Air Force.

Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, CVO, OBE was a notable explorer from County Kildare, Ireland, who was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration...

's last Antarctic

Antarctic

The Antarctic is the region around the Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica and the ice shelves, waters and island territories in the Southern Ocean situated south of the Antarctic Convergence...

project, and the final episode in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration defines an era which extended from the end of the 19th century to the early 1920s. During this 25-year period the Antarctic continent became the focus of an international effort which resulted in intensive scientific and geographical exploration, sixteen...

. The venture, financed by businessman John Quiller Rowett

John Quiller Rowett

John Quiller Rowett was a British businessman who made a fortune in the spirits industry. He had a desire, however, to do more than make money, and in the years after the First World War he was a notable contributor to public and charitable causes...

, is sometimes referred to as the Quest Expedition after its ship Quest

Quest (ship)

The Quest, a low-powered, schooner-rigged steamship that sailed from 1917 until sinking in 1962, is best known as the polar exploration vessel of the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition of 1921-1922. It was aboard this vessel that Sir Ernest Shackleton died on 5 January 1922 while the vessel was in...

, a converted Norwegian sealer. Shackleton's original plan had been to explore the Beaufort Sea

Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and Alaska, west of Canada's Arctic islands. The sea is named after hydrographer Sir Francis Beaufort...

sector of the Arctic Ocean

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean, located in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar region, is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceanic divisions...

, but this was abandoned after the Canadian government withheld financial support. Quest, smaller than any recent Antarctic exploration vessel, soon proved inadequate for its task, and progress south was delayed by its poor sailing performance and by frequent engine problems. Before the expedition's work could properly begin, Shackleton died aboard ship, just after its arrival at the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia.

The major part of the subsequent attenuated expedition was a three-month cruise to the eastern Antarctic, under the leadership of second-in-command Frank Wild

Frank Wild

Commander John Robert Francis Wild CBE, RNVR, FRGS , known as Frank Wild, was an explorer...

. In these waters the shortcomings of Quest were soon in evidence: slow speed, heavy fuel consumption, a tendency to roll in heavy seas, and a steady leak. The ship was unable to proceed further than longitude

Longitude

Longitude is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east-west position of a point on the Earth's surface. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees, minutes and seconds, and denoted by the Greek letter lambda ....

20°E, well short of its easterly target, and its engine's low power was insufficient for it to penetrate far into the Antarctic ice. Following several fruitless attempts to break southwards through the pack ice, Wild returned the ship to South Georgia, after a nostalgic visit to Elephant Island, where he and 21 others had been stranded after the sinking of the ship Endurance

Endurance (1912 ship)

The Endurance was the three-masted barquentine in which Sir Ernest Shackleton sailed for the Antarctic on the 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition...

, during Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition , also known as the Endurance Expedition, is considered the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent...

six years earlier.

Wild had thoughts of a second, more productive season in the ice, and took the ship to Cape Town

Cape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

for a refit. Here he received a message from Rowett ordering the ship home to England, so the expedition ended quietly. Although not greatly regarded in the histories of polar exploration, the Quest voyage's significance is its standing at the very end of the Heroic Age and the beginning of the "Mechanical Age" that followed. Ultimately, however, the event that defined it in public memory, and overshadowed all its activities, was Shackleton's untimely death.

After the

Endurance After helping to rescue the various stranded groups of men from his Endurance expedition, Shackleton came home to Britain in late May 1917, while World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

was raging. Too old to enlist, he nevertheless sought an active role in the war effort, and eventually departed for Murmansk

Murmansk

Murmansk is a city and the administrative center of Murmansk Oblast, Russia. It serves as a seaport and is located in the extreme northwest part of Russia, on the Kola Bay, from the Barents Sea on the northern shore of the Kola Peninsula, not far from Russia's borders with Norway and Finland...

with the temporary army rank of major

Major

Major is a rank of commissioned officer, with corresponding ranks existing in almost every military in the world.When used unhyphenated, in conjunction with no other indicator of rank, the term refers to the rank just senior to that of an Army captain and just below the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

, as part of a military mission to North Russia. This role was not satisfying to Shackleton, and he expressed his dissatisfaction in letters home: "I feel I am no use to anyone unless I am outfacing the storm in wild lands." He returned to England in February 1919 and began plans to set up a company that would, with the cooperation of the North Russian Government

White movement

The White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

, develop the natural resources of the region. This scheme came to nothing, as the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

took control of that part of Russia during the Russian Civil War

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War was a multi-party war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed to the Soviets, under the domination of the Bolshevik party. Soviet forces first assumed power in Petrograd The Russian Civil War (1917–1923) was a...

, and Shackleton was forced to rely on the lecture circuit to provide him with an income. At the Philharmonic Hall in Great Portland Street

Great Portland Street

Great Portland Street is a street in the West End of London. Linking Oxford Street with Albany Street and the busy A501 Marylebone Road and Euston Road, the road forms the boundary between Fitzrovia to the east and Marylebone to the west...

, London, during the winter of 1919–20, he lectured twice a day, six days a week, for five months. At the same time, despite the large debts still outstanding from the Endurance expedition, he began planning a new exploration venture.

Canadian proposal

Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and Alaska, west of Canada's Arctic islands. The sea is named after hydrographer Sir Francis Beaufort...

". This area of the Arctic ocean, to the north of Alaska

Alaska

Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area. It is situated in the northwest extremity of the North American continent, with Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, with Russia further west across the Bering Strait...

and west of the Canadian Arctic archipelago

Canadian Arctic Archipelago

The Canadian Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Arctic Archipelago, is a Canadian archipelago north of the Canadian mainland in the Arctic...

, was largely unexplored; Shackleton believed, on the basis of tidal records, that the sea held large undiscovered land masses that "would be of the greatest scientific interest to the world, apart from the possible economic value". He also hoped to reach the northern "pole of inaccessibility", the most remote point in the Arctic regions. In March 1920, his plans received the general approval of the Royal Geographical Society

Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society is a British learned society founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical sciences...

(RGS) and were supported by the Canadian government. On this basis Shackleton set about acquiring the necessary funding, which he estimated at £50,000 (about £1.6 million, 2008 value). Later that year, Shackleton met by chance an old school-friend, John Quiller Rowett

John Quiller Rowett

John Quiller Rowett was a British businessman who made a fortune in the spirits industry. He had a desire, however, to do more than make money, and in the years after the First World War he was a notable contributor to public and charitable causes...

, who agreed to put up a nucleus of cash to enable Shackleton to get started. With this money Shackleton was able, in January 1921, to acquire the wooden Norwegian whaler Foca I, and to proceed with the purchase of other equipment and the hiring of a crew.

In May 1921 the Canadian plans were abandoned. The policy of the government of Canada on the funding of expeditions changed with the advent of a new Prime Minister, Arthur Meighen

Arthur Meighen

Arthur Meighen, PC, QC was a Canadian lawyer and politician. He served two terms as the ninth Prime Minister of Canada: from July 10, 1920 to December 29, 1921; and from June 29 to September 25, 1926. He was the first Prime Minister born after Confederation, and the only one to represent a riding...

, who withdrew support from Shackleton's proposal . Shackleton's response was not to cancel the expedition but to reorient it. In the middle of May his associate Alexander Macklin

Alexander Macklin

Alexander Hepburne Macklin OBE MC TD was a British doctor who served as one of the two surgeons on Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917. In 1922 he joined Shackleton on his last expedition on the Quest.-Early life:Alexander Macklin was born in 1889 in...

, who was in Canada negotiating the purchase of dogs, received a telegram notifying him that the destination was now to be the Antarctic; a varied programme of exploration, coastal mapping, mineral prospecting and oceanographic research in southern waters had been substituted for the Beaufort Sea venture.

Objectives

Even before his impasse with the Canadian government, Shackleton had been considering a southern expedition as a possible alternative to the Beaufort Sea. According to RGS librarian Hugh Robert MillHugh Robert Mill

Hugh Robert Mill was a Scottish geographer and meteorologist who was influential in the reform of geography teaching, and in the development of meteorology as a science. Educated in Scotland, he graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 1883...

, as early as March 1920 Shackleton had talked about two possible schemes—the Beaufort Sea exploration and "an oceanographical expedition with the object of visiting all the little-known islands of the South Atlantic and South Pacific". By June 1921, it had expanded to include a circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent and the mapping of around 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of uncharted coastline. It would also encompass a search for "lost" or wrongly charted sub-Antarctic islands (including Dougherty Island, Tuanaki

Tuanaki

Tuanaki or Tuanahe is the name of a vanished group of islets, once part of the Cook Islands. It was located south of Rarotonga and within two days sail of Mangaia....

, and the Nimrod Islands

Nimrod Islands

The Nimrod Islands were a group of islands first reported in 1828 by Captain Eilbeck of the ship Nimrod while sailing from Port Jackson around Cape Horn...

), investigations of possible mineral resources to be exploited in these rediscovered lands, and an ambitious scientific research program. This was to include soundings around Gough Island

Gough Island

Gough Island , also known historically as Gonçalo Álvares or Diego Alvarez, is a volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a dependency of Tristan da Cunha and part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha...

to investigate an alleged "underwater continental connection between Africa and America." Shackleton biographer Margery Fisher calls the plan "diffuse", and "far too comprehensive for one small body of men to tackle within two years". According to biographer Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford is an author, principally of biographies of Polar explorers. He lives in Cambridge, and was formerly Scandinavian correspondent of The Observer, also acting as their winter sports correspondent...

the expedition had no obvious goal and was "only too clearly a piece of improvisation, a pretext [for Shackleton] to get away".

Crow's nest

A crow's nest is a structure in the upper part of the mainmast of a ship or structure, that is used as a lookout point.This position ensured the best view of the approaching hazards, other ships or land. It was the best device for this purpose until the invention of radar.In early ships it was...

was electrically heated; there were heated overalls for the lookouts, a wireless set, and a device called an odograph which could trace and chart the ship's route automatically. Photography was to figure prominently, and "a large and expensive outfit of cameras, cinematographical machines and general photographic appliances [was] acquired". Among the oceanographical research equipment was a Lucas deep-sea sounding machine.

This ample provision arose from the sponsorship of Rowett, who had extended his original gift of seed money

Seed money

Seed money, sometimes known as seed funding, friends and family funding or angel funding , is a securities offering whereby one or more parties that have some connection to a new enterprise invest the funds necessary to start the business so that it has enough funds to sustain itself for a period...

to an undertaking to cover the costs of the entire expedition. The extent of Rowett's contribution is not recorded; in an (undated) prospectus for the southern expedition Shackleton had estimated the total cost as "about £100,000". Whatever the total, Rowett appears to have funded the lion's share, enabling Frank Wild to record later that, unique among Antarctic expeditions of the era, this one returned home without any outstanding debt. According to Wild, without Rowett's actions the expedition would have been impossible: "His generous attitude is the more remarkable in that he knew there was no prospect of financial return, and what he did was in the interest of scientific research and from friendship with Shackleton." His only recognition was the attachment of his name to the title of the expedition. Rowett was, according to Huntford, "a stodgy, prosaic looking" businessman, who was, in 1920, a co-founder and principal contributor to an animal nutrition research institute in Aberdeen

Aberdeen

Aberdeen is Scotland's third most populous city, one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas and the United Kingdom's 25th most populous city, with an official population estimate of ....

known as the Rowett Research Institute

Rowett Research Institute

The Rowett Research Institute is a research centre for studies into food and nutrition located in Aberdeen, Scotland.-History:The institute was founded in 1913 when the University of Aberdeen and the North of Scotland College of Agriculture agreed that an "Institute for Research into Animal...

(now part of the University of Aberdeen

University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen, an ancient university founded in 1495, in Aberdeen, Scotland, is a British university. It is the third oldest university in Scotland, and the fifth oldest in the United Kingdom and wider English-speaking world...

). He had also endowed dental research work at the Middlesex Hospital

Middlesex Hospital

The Middlesex Hospital was a teaching hospital located in the Fitzrovia area of London, United Kingdom. First opened in 1745 on Windmill Street, it was moved in 1757 to Mortimer Street where it remained until it was finally closed in 2005. Its staff and services were transferred to various sites...

. Rowett did not live long after the return of the expedition; in 1924, aged 50, he took his own life following an apparent downturn in his business fortunes.

Quest

Stem (ship)

The stem is the very most forward part of a boat or ship's bow and is an extension of the keel itself and curves up to the wale of the boat. The stem is more often found on wooden boats or ships, but not exclusively...

, with an awkward square rig

Square rig

Square rig is a generic type of sail and rigging arrangement in which the primary driving sails are carried on horizontal spars which are perpendicular, or square, to the keel of the vessel and to the masts. These spars are called yards and their tips, beyond the last stay, are called the yardarms...

, and a tendency to wallow in heavy seas. Fisher reports that she was built in 1917, weighed 204 tons, and had a large and spacious deck. Although she had some modern facilities, such as electric lights in the cabins, she was unsuited to long oceanic voyages; Shackleton, on the first day out, observed that "in no way are we shipshape or fitted to ignore even the mildest storm". Leif Mills, in his biography of Frank Wild

Frank Wild

Commander John Robert Francis Wild CBE, RNVR, FRGS , known as Frank Wild, was an explorer...

, says that had the ship been taken to the Beaufort Sea in accordance with Shackleton's original plans, she would probably have been crushed in the Arctic pack ice. On her voyage south she suffered frequent damage and breakdowns, requiring repairs at every port of call.

Personnel

The TimesThe Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

newspaper had reported that Shackleton planned to take a dozen men to the Arctic, "chiefly those who had accompanied him on earlier expeditions". In actuality, Quest left London for the south with 20 men, of whom eight were old Endurance comrades; another, James Dell, was a veteran from the Discovery, 20 years previously. Some of the Endurance hands had not been fully paid from the earlier expedition, but were prepared to join Shackleton again out of personal loyalty.

Frank Worsley

Frank Arthur Worsley DSO and Bar, OBE, RD was a New Zealand sailor and explorer.After serving in the Pacific, and especially in the New Zealand Post Office's South Pacific service he joined Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of...

, Endurances former captain, became captain of Quest. Other old comrades included the two surgeons, Alexander Macklin

Alexander Macklin

Alexander Hepburne Macklin OBE MC TD was a British doctor who served as one of the two surgeons on Sir Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917. In 1922 he joined Shackleton on his last expedition on the Quest.-Early life:Alexander Macklin was born in 1889 in...

and James McIlroy, the meteorologist Leonard Hussey

Leonard Hussey

Leonard Duncan Albert Hussey OBE was an English meteorologist, archeologist, explorer and member of Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic and Shackleton–Rowett Expeditions...

, the engineer Alfred Kerr, seaman Tom McLeod and cook Charles Green. Shackleton had assumed that Tom Crean would sign up, and had assigned him duties "in charge of boats", but Crean had retired from the navy to start a family back home in County Kerry

County Kerry

Kerry means the "people of Ciar" which was the name of the pre-Gaelic tribe who lived in part of the present county. The legendary founder of the tribe was Ciar, son of Fergus mac Róich. In Old Irish "Ciar" meant black or dark brown, and the word continues in use in modern Irish as an adjective...

, and declined Shackleton's invitation.

Of the newcomers, Roderick Carr

Roderick Carr

Air Marshal Sir Charles Roderick Carr KBE, CB, DFC, AFC was a senior Royal Air Force commander from New Zealand. He held high command in World War II and served as Chief of the Indian Air Force.-Military career:...

, a New Zealand-born Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

pilot, was hired to fly the expedition's aeroplane, an Avro "Antarctic" Baby: an Avro Baby

Avro Baby

-External links:* Contemporary technical description with photographs and drawings....

modified as a seaplane with an 80-horse power engine. He had met Shackleton in North Russia, and had recently been serving as Chief of Staff to the Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

n air force. In fact, the aeroplane was not used during the expedition due to some missing parts, and Carr therefore assisted with the scientific work. The scientific staff included Australian biologist

Biologist

A biologist is a scientist devoted to and producing results in biology through the study of life. Typically biologists study organisms and their relationship to their environment. Biologists involved in basic research attempt to discover underlying mechanisms that govern how organisms work...

Hubert Wilkins, who had Arctic experience, and the Canadian geologist

Geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid and liquid matter that constitutes the Earth as well as the processes and history that has shaped it. Geologists usually engage in studying geology. Geologists, studying more of an applied science than a theoretical one, must approach Geology using...

Vibert Douglas, who had initially signed for the aborted Beaufort Sea expedition. The recruits who caught the most public attention were two members of the Boy Scouts' movement, Norman Mooney and James Marr. As the result of publicity organised by the Daily Mail

Daily Mail

The Daily Mail is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust. First published in 1896 by Lord Northcliffe, it is the United Kingdom's second biggest-selling daily newspaper after The Sun. Its sister paper The Mail on Sunday was launched in 1982...

newspaper, these two had been selected to join the expedition out of around 1,700 Scouts who had applied to go. Mooney, who was from the Orkney Islands

Orkney Islands

Orkney also known as the Orkney Islands , is an archipelago in northern Scotland, situated north of the coast of Caithness...

, soon dropped out, leaving the ship at Madeira

Madeira

Madeira is a Portuguese archipelago that lies between and , just under 400 km north of Tenerife, Canary Islands, in the north Atlantic Ocean and an outermost region of the European Union...

after suffering chronic seasickness. Marr, an 18-year-old from Aberdeen

Aberdeen

Aberdeen is Scotland's third most populous city, one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas and the United Kingdom's 25th most populous city, with an official population estimate of ....

, remained with the expedition throughout, winning plaudits from Shackleton and Wild for his application to the tasks at hand. After being put to work in the ship's coal bunkers, according to Wild, Marr "came out of the trial very well, showing an amount of hardihood and endurance that was remarkable".

Voyage south

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

. Large crowds gathered on the banks of the river and on the bridges, to witness the event. Marr wrote in his diary that it was as though "all London had conspired together to bid us a heartening farewell".

Shackleton's original intention was to sail down to Cape Town

Cape Town

Cape Town is the second-most populous city in South Africa, and the provincial capital and primate city of the Western Cape. As the seat of the National Parliament, it is also the legislative capital of the country. It forms part of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality...

, visiting the main South Atlantic islands on the way. From Cape Town, Quest would head for the Enderby Land

Enderby Land

Enderby Land is a projecting land mass of Antarctica, extending from Shinnan Glacier at to William Scoresby Bay at .Enderby Land was discovered in February 1831 by John Biscoe in the whaling brig Tula, and named after the Enderby Brothers of London, owners of the Tula, who encouraged their...

coast of Antarctica where, once in the ice, it would explore the coastline in the direction of Coats Land

Coats Land

Coats Land is a region in Antarctica which lies westward of Queen Maud Land and forms the eastern shore of the Weddell Sea, extending in a general northeast-southwest direction between 20º00´W and 36º00´W. The northeast part was discovered from the Scotia by William S. Bruce, leader of the Scottish...

in the Weddell Sea

Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha Coast, Queen Maud Land. To the east of Cape Norvegia is...

. At the end of the summer season the ship would visit South Georgia before returning to Cape Town for refitting and preparation for the second year's work. However, the ship's performance in the early stages of the voyage disrupted this schedule. Serious problems with the engine necessitated a week's stay in Lisbon

Lisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

, and further stops in Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands. These delays and the slow speed of the ship led Shackleton to decide that it would be necessary to sacrifice entirely the visits to the South Atlantic islands, and instead he turned the ship towards Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro , commonly referred to simply as Rio, is the capital city of the State of Rio de Janeiro, the second largest city of Brazil, and the third largest metropolitan area and agglomeration in South America, boasting approximately 6.3 million people within the city proper, making it the 6th...

, where the engine could receive a thorough overhaul. Quest reached Rio on 22 November 1921.

The engine overhaul, and the replacement of the damaged topmast, delayed the party in Rio for four weeks. This meant that it was no longer practical to proceed to Cape Town and then on to the ice. Instead, Shackleton decided that the ship would sail directly to Grytviken

Grytviken

Grytviken is the principal settlement in the British territory of South Georgia in the South Atlantic. It was so named in 1902 by the Swedish surveyor Johan Gunnar Andersson who found old English try pots used to render seal oil at the site. It is the best harbour on the island, consisting of a...

harbour in South Georgia. Equipment and stores that had been sent on to Cape Town would have to be sacrificed, but Shackleton evidently hoped that this shortfall could be made up in South Georgia. He was vague about the direction the expedition should take after South Georgia; Macklin wrote in his diary, "The Boss says...quite frankly that he does not know what he will do."

Death of Shackleton

On 17 December, the day before Quest was due to leave Rio, Shackleton fell ill. He may have suffered a heart attack; Macklin was called, but Shackleton refused to be examined and declared himself "better" the next morning. On the ensuing voyage to South Georgia he was, from the accounts of his shipmates, unusually subdued and listless. He also began drinking champagne each morning, "to deaden the pain", contrary to his normal rule of not allowing liquor at sea. A severe storm ruined the expedition's proposed Christmas celebrations, and a new problem with the engine's steam furnace slowed progress and caused Shackleton further stress. By 1 January 1922, the weather had abated: "Rest and calm after the storm – the year has begun kindly for us", wrote Shackleton in his diary. On 4 January 1922, South Georgia was sighted, and late that morning Quest anchored at Grytviken.After visiting the whaling establishment ashore, Shackleton returned to the ship apparently refreshed. He told Frank Wild that they would celebrate their deferred Christmas the next day, and retired to his cabin to write his diary. "The old smell of dead whale permeates everything", he wrote. "It is a strange and curious place....A wonderful evening. In the darkening twilight I saw a lone star hover, gem like above the bay." Later he slept, and was heard snoring by the surgeon McIlroy, who had just finished his watch-keeping duty. Shortly after 2 a.m. on the morning of 5 January, Macklin, who had taken over the watch, was summoned to Shackleton's cabin. According to Macklin's diary, he found Shackleton complaining of back pains and severe facial neuralgia, and asking for a painkilling drug. In a brief discussion, Macklin told his leader that he had been overdoing things, and needed to lead a more regular life. Macklin records Shackleton as saying: "You're always wanting me to give up things, what is it I ought to give up?" Macklin replied "Chiefly alcohol, Boss, I don't think it agrees with you." Immediately afterwards Shackleton "had a very severe paroxysm, during which he died".

The death certificate, signed by Macklin, gave the cause as "Atheroma of the Coronary arteries and Heart failure"—in modern terms, coronary thrombosis

Coronary thrombosis

Coronary thrombosis is a form of thrombosis affecting the coronary circulation. It is associated with stenosis subsequent to clotting. The condition is considered as a type of ischaemic heart disease.It can lead to a myocardial infarction...

. Later that morning Wild, now in command, gave the news to the shocked crew, and told them that the expedition would carry on. The body was brought ashore for embalming before its return to England. On 19 January, Leonard Hussey accompanied the body aboard a steamer bound for Montevideo

Montevideo

Montevideo is the largest city, the capital, and the chief port of Uruguay. The settlement was established in 1726 by Bruno Mauricio de Zabala, as a strategic move amidst a Spanish-Portuguese dispute over the platine region, and as a counter to the Portuguese colony at Colonia del Sacramento...

, but on arrival there he found a message from Lady Shackleton, requesting that the body be returned to South Georgia for burial. Hussey accompanied the body aboard a British steamer, and returned to Grytviken. Here, on 5 March, Shackleton was buried in the Norwegian cemetery; Quest had meantime sailed, so only Hussey of Shackleton's former comrades was present. A rough cross marked the grave, until it was replaced by a tall granite column six years later.

Voyage to the ice

As leader, Wild had first to decide where the expedition should now go. Kerr reported that the furnace problem was manageable, and after supplementing stores and equipment with what was available in South Georgia, Wild decided to proceed in general accordance with Shackleton's original plans. He would take the ship eastward towards Bouvet IslandBouvet Island

Bouvet Island is an uninhabited Antarctic volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean, 2,525 km south-southwest of South Africa. It is a dependent territory of Norway and, lying north of 60°S latitude, is not subject to the Antarctic Treaty. The centre of the island is an ice-filled crater of an...

and then beyond, before turning south to enter the ice as close as possible to Enderby Land, and begin coastal survey work there. The expedition would also investigate an "Appearance of Land"

Phantom island

Phantom islands are islands that were believed to exist, and appeared on maps for a period of time during recorded history, but were later removed after they were proved to be nonexistent...

in the mouth of the Weddell Sea, reported by Sir James Clark Ross in 1842, but not seen since. Ultimately, however, progress would depend on weather, ice conditions, and the capabilities of the ship.

Quest left South Georgia on 18 January, heading south-east towards the South Sandwich Islands. There was a heavy swell

Swell (ocean)

A swell, in the context of an ocean, sea or lake, is a series surface gravity waves that is not generated by the local wind. Swell waves often have a long wavelength but this varies with the size of the water body, e.g. rarely more than 150 m in the Mediterranean, and from event to event, with...

, such that the overladen ship frequently dipped its gunwales below the waves, filling the waist with water. As they proceeded, Wild wrote that Quest rolled like a log, was leaking and required regular pumping, was heavy on coal consumption, and was slow. All these factors led him, at the end of January, to change his plan. Bouvet Island was abandoned in favour of a more southerly course that brought them to the edge of the pack ice on 4 February.

"Now the little Quest can really try her mettle", wrote Wild, as the ship entered the loose pack. He noted that Quest was the smallest ship ever to attempt to penetrate the heavy Antarctic ice, and pondered on the fate of others. "Shall we escape, or will the Quest join the ships in Davy Jones's Locker?" During the days that followed, as they moved southward in falling temperatures, the ice thickened. On 12 February they reached the most southerly latitude they would attain, 69°17'S, and their most easterly longitude, 17°9'E, well short of Enderby Land. Noting the state of the sea ice and fearing being frozen in, Wild "beat a hasty and energetic retreat" to the north and west. Wild still hoped to tackle the heavy ice, and if possible to break through to the hidden land beyond. On 18 February he turned the ship south again for another try, but was no more successful than before. On 24 February, after a series of further efforts had failed, Wild set a course westward across the mouth of the Weddell Sea. The ship would try to visit Elephant Island in the South Shetlands

South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of Antarctic islands, lying about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, with a total area of . By the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, the Islands' sovereignty is neither recognized nor disputed by the signatories and they are free for use by any signatory for...

, before returning to South Georgia on the onset of winter.

For the most part, the long passage across the Weddell Sea proceeded uneventfully. Wild and Worsley were not hitting it off, according to Macklin, and there was other discontent among the crew which Wild, in his own account, dealt with by the threat of "the most drastic treatment". On 12 March they reached 64°11'S, 46°4'W, which was the area where Ross had recorded an "Appearance of Land" in 1842, but there was no sign of it, and a depth sounding of over 2,300 fathoms (13,800 ft, 4,200 m.) indicated no likelihood of land nearby. Between 15–21 March Quest was frozen into the ice, and the shortage of coal became a major concern. When the ship broke free, Wild set a course directly for Elephant Island, where he hoped that the coal supply could be supplemented by blubber

Blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of vascularized adipose tissue found under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds and sirenians.-Description:Lipid-rich, collagen fiber–laced blubber comprises the hypodermis and covers the whole body, except for parts of the appendages, strongly attached to the musculature...

from the elephant seal

Elephant seal

Elephant seals are large, oceangoing seals in the genus Mirounga. There are two species: the northern elephant seal and the southern elephant seal . Both were hunted to the brink of extinction by the end of the 19th century, but numbers have since recovered...

s there. On 25 March the island was sighted. Wild wanted if possible to revisit Cape Wild, the site of the old Endurance expedition camp, but bad weather prevented this. They viewed the site through binoculars, picking out the old landmarks, before landing on the western coast to hunt for elephant seals. They were able to obtain sufficient blubber to mix with the coal so that, with a favourable wind, they managed to reach South Georgia on 6 April.

Return

Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha is a remote volcanic group of islands in the south Atlantic Ocean and the main island of that group. It is the most remote inhabited archipelago in the world, lying from the nearest land, South Africa, and from South America...

, a remote inhabited island to the west and south of Cape Town. Here, on the orders of the Chief Scout

Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell

Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, Bt, OM, GCMG, GCVO, KCB , also known as B-P or Lord Baden-Powell, was a lieutenant-general in the British Army, writer, and founder of the Scout Movement....

, Marr was to present a flag to the local Scout Troop. After a rough crossing of the "Roaring Forties

Roaring Forties

The Roaring Forties is the name given to strong westerly winds found in the Southern Hemisphere, generally between the latitudes of 40 and 49 degrees. Air displaced from the Equator towards the South Pole, which travels close to the surface between the latitudes of 30 and 60 degrees south, combines...

", Quest arrived at Tristan da Cunha on 20 May.

During the five-day stay, with the help of some of the islanders, the expedition made brief landings on the small Inaccessible Island, 20 miles (32.2 km) south-west of Tristan, and visited the even smaller Nightingale Island

Nightingale Island

Nightingale Island is an island in the South Atlantic Ocean, 3 km² in area, part of the Tristan da Cunha group of islands. They are administered by the United Kingdom as part of the overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha....

, collecting specimens. Wild's impressions of the stay at Tristan were not altogether favourable. He noted the appalling squalor and poverty, and said of the population: "They are ignorant, shut off almost completely from the world, horribly limited in outlook." Despite these reservations, the Scout parade and flag presentation took place before Quest sailed on to Gough Island

Gough Island

Gough Island , also known historically as Gonçalo Álvares or Diego Alvarez, is a volcanic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a dependency of Tristan da Cunha and part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha...

, 200 miles (321.9 km) to the east. Here members of the expedition took geological and botanical samples. They arrived at Cape Town on 18 June, to be greeted by enthusiastic crowds. The South African Prime Minister, Jan Smuts

Jan Smuts

Jan Christiaan Smuts, OM, CH, ED, KC, FRS, PC was a prominent South African and British Commonwealth statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various cabinet posts, he served as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 until 1924 and from 1939 until 1948...

, gave a official reception for them, and they were honoured at dinners and lunches by local organisations.

They were also met by Rowett's agent, with the message that they should return to England. Wild wrote: "I should have liked one more season in the Enderby Quadrant...much might be accomplished by making Cape Town our starting point and setting out early in the season." However, on 19 July they left Cape Town and sailed northwards. Their final visits were to St Helena, Ascension Island

Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island in the equatorial waters of the South Atlantic Ocean, around from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America, which is roughly midway between the horn of South America and Africa...

and St Vincent

São Vicente, Cape Verde

São Vicente , also Son Visent or Son Sent in Cape Verdean Creole, is one of the Barlavento islands of Cape Verde. It is located between the islands of Santo Antão and Santa Luzia, with the Canal de São Vicente separating it from Santo Antão.- Geography :The island is roughly rectangular in shape...

. On 16 September, one year after departure, they arrived at Plymouth Harbour

Plymouth

Plymouth is a city and unitary authority area on the coast of Devon, England, about south-west of London. It is built between the mouths of the rivers Plym to the east and Tamar to the west, where they join Plymouth Sound...

.

Assessment

According to Wild, the expedition ended "quietly", although his biographer Leif Mills writes of enthusiastic crowds in Plymouth Sound. At the end of his account, Wild expressed the hope that the information they had brought back might "prove of value in helping to solve the great natural problems that still beset us". These results were summarised in five brief appendices to Wild's book. The summaries reflected the efforts of the scientific staff to collect data and specimens at each port of call, and the geological and survey work carried out by Carr and Douglas on South Georgia, before the southern voyage. Eventually a few scientific papers and articles were developed from this material, but it was, in Leif Mills's words, "little enough to show for a year's work".The lack of a clear, defined expedition objective was aggravated by the failure to call at Cape Town on the way south, with the result that important equipment was not picked up. On South Georgia, Wild found little that could make up for this loss—there were no dogs on the island, so no sledging work could be carried out, which eliminated Wild's preferred choice of a revised expedition goal, an exploration of Graham Land

Graham Land

Graham Land is that portion of the Antarctic Peninsula which lies north of a line joining Cape Jeremy and Cape Agassiz. This description of Graham Land is consistent with the 1964 agreement between the British Antarctic Place-names Committee and the US Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names, in...

on the Antarctic peninsula

Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula is the northernmost part of the mainland of Antarctica. It extends from a line between Cape Adams and a point on the mainland south of Eklund Islands....

. The death of Shackleton before the beginning of serious work was a heavy blow, and questions were raised about the adequacy of Wild as his replacement. Some reports have Wild drinking heavily—"practically an alcoholic", according to Shackleton's biographer, Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford

Roland Huntford is an author, principally of biographies of Polar explorers. He lives in Cambridge, and was formerly Scandinavian correspondent of The Observer, also acting as their winter sports correspondent...

. Mills suggests, however, that even if Shackleton had lived to complete the expedition, it is arguable whether, under the circumstances, it could have achieved more than it did under Wild's command. On the voyage south, colleagues had been struck by the changes in Shackleton—his listlessness, docility and vacillation.

As for technical innovation, the failure of the aeroplane to fly was another disappointment. Shackleton's hopes had been high that he could pioneer the use of this form of transport in Antarctic waters, and he had discussed this issue with the British Air Ministry

Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the British Government with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964...

. According to Fisher's account, essential aeroplane parts had been sent on to Cape Town, but remained uncollected. The long-range, 220-volt wireless equipment did not work properly and was abandoned early on. The smaller, 110-volt equipment worked only within a range of 250 miles (402.3 km). During the Tristan visit, Wild attempted to install a new wireless apparatus with the help of a local missionary, but this was also unsuccessful.

End of the Heroic Age

An Antarctic hiatus followed the return of Quest, there being no significant expeditions to the region for seven years. The expeditions that then followed were of a different character from their predecessors, belonging to the "mechanical age" that succeeded the Heroic Age.At the end of his narrative of the Quest expedition, Wild wrote of the Antarctic: "I think that my work there is done"; he never returned, closing a career which, like Shackleton's, had bracketed the Heroic Age. None of the expedition members who were veterans from the Endurance returned to the Antarctic, although Worsley made one voyage to the Arctic in 1925. Of the other crew and staff of Quest, the Australian naturalist Hubert Wilkins

Hubert Wilkins

Sir Hubert Wilkins MC & Bar was an Australian polar explorer, ornithologist, pilot, soldier, geographer and photographer.-Early life:...

became a pioneer aviator in both the Arctic and Antarctic, in 1928 flying from Point Barrow

Point Barrow

Point Barrow or Nuvuk is a headland on the Arctic coast in the U.S. state of Alaska, northeast of Barrow. It is the northernmost point of all the territory of the United States, at...

, Alaska to Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen is the largest and only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in Norway. Constituting the western-most bulk of the archipelago, it borders the Arctic Ocean, the Norwegian Sea and the Greenland Sea...

. He also made several unsuccessful attempts during the 1930s, in collaboration with the American adventurer Lincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth was an arctic explorer from the United States.-Birth:He was born on May 12, 1880 to James Ellsworth and Eva Frances Butler in Chicago, Illinois...

, to fly to the South Pole. James Marr, the Boy Scout, also became an Antarctic regular after qualifying as a marine biologist, joining several Australian expeditions in the late 1920s and 1930s. Roderick Carr, the frustrated pilot, became an Air Marshal

Air Marshal

Air marshal is a three-star air-officer rank which originated in and continues to be used by the Royal Air Force...

in the Royal Air Force.

Sources

- The Agricultural Association, the Development Fund, and the Origins of the Rowett Research Institute PDF. British Agricultural and Horticultural Society