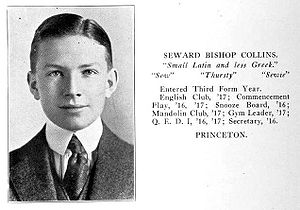

Seward Collins

Encyclopedia

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

".

Biography

Collins graduated from Princeton UniversityPrinceton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

and entered New York's literary life in 1926, as a bon vivant. He knew many literary giants of his day, had an affair with Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker

Dorothy Parker was an American poet, short story writer, critic and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks, and eye for 20th century urban foibles....

, and amassed a large collection of erotica

Erotica

Erotica are works of art, including literature, photography, film, sculpture and painting, that deal substantively with erotically stimulating or sexually arousing descriptions...

. His bookstore, The American Review Bookshop, was at 231 West 58th Street in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

. It carried many journals, broadsheets and newsletters that supported nationalist

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

and fascist

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

causes in Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and Asia

Asia

Asia is the world's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres. It covers 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area and with approximately 3.879 billion people, it hosts 60% of the world's current human population...

.

In 1936, he married Dorothea Brande

Dorothea Brande

Dorothea Brande was a well-respected writer and editor in New York.She was born in Chicago and attended the University of Chicago, the Lewis Institute in Chicago , and the University of Michigan...

. A man of independent wealth, Collins published two literary journals: The Bookman

The Bookman (New York)

The Bookman was a literary journal established in 1895 by Dodd, Mead and Company. It drew its name from the phrase, "I am a Bookman," by James Russell Lowell; the phrase regularly appeared on the cover and title page of the bound edition. It was purchased in 1918 by the George H. Doran Company. In...

(1927–1933) and The American Review (1933–1937).

Collins was infatuated with the writings of prominent humanists

Humanism

Humanism is an approach in study, philosophy, world view or practice that focuses on human values and concerns. In philosophy and social science, humanism is a perspective which affirms some notion of human nature, and is contrasted with anti-humanism....

of his day, including Paul Elmer More

Paul Elmer More

Paul Elmer More was an American journalist, critic, essayist and Christian apologist.-Biography:More was educated at Washington University in St. Louis and Harvard University...

and Irving Babbitt

Irving Babbitt

Irving Babbitt was an American academic and literary critic, noted for his founding role in a movement that became known as the New Humanism, a significant influence on literary discussion and conservative thought in the period between 1910 to 1930...

. Politically, he moved from left-liberalism in the early 1920s and eventually away from More's and Babbitt's Humanism

Humanism

Humanism is an approach in study, philosophy, world view or practice that focuses on human values and concerns. In philosophy and social science, humanism is a perspective which affirms some notion of human nature, and is contrasted with anti-humanism....

to what he called "fascism" by the end of the decade. In The American Review, he sought to develop an American form of fascism and praised Italian dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

and German dictator Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

in an article titled "Monarch as Alternative," which appeared in the first issue in 1933. In that essay, Collins attacked both capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

and communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and heralded the "New Monarch," who would champion the common good over and against the machinations of capitalists and communists. His praise of Hitler was grounded in his belief that Hitler's rise to power that year heralded the end of the communist threat, as is illustrated by this excerpt:

One would gather from the fantastic lack of proportion of our press—not to say its gullibility and sensationalism—that the most important aspect of the GermanNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

revolution was the hardships suffered by Jews under the new regime. Even if the absurd atrocity stories were all true, the fact would be almost negligible beside an event that shouts aloud in spite of the journalistic silence: the victory of Hitler signifies the end of the Communist threat, forever. Wherever Communism grows strong enough to make a Communist revolution a danger, it will be crushed by a Fascist revolution.

In a 1936 interview that he granted to Grace Lumpkin

Grace Lumpkin

Grace Lumpkin was an American writer of proletarian literature, focusing most of her works on the Depression era and the rise and fall of favor surrounding communism in the United States...

in the pro-communist periodical FIGHT against War and Fascism

FIGHT against War and Fascism

FIGHT Against War and Fascism was an anti-fascist broadsheet published in the United States by the American League Against War and Fascism from 1934 until 1938.It was sponsored by socialists and communists...

, Collins stated: "I am a fascist. I admire Hitler and Mussolini very much. They have done great things for their countries." When Lumpkin objected to Hitler's persecution of the Jews, Collins replied: "It is not persecution. The Jews make trouble. It is necessary to segregate them."

The American Review ran articles by many leading literary critics of the day, including the Southern Agrarians

Southern Agrarians

The Southern Agrarians were a group of twelve American writers, poets, essayists, and novelists, all with roots in the Southern United States, who joined together to write a pro-Southern agrarian manifesto, a...

, who, though hardly fascists, accepted a Northern publisher for their anti-modern essays. Several of them came to regret (and renounce) their relationship with Collins, however, after his political views became better known. One of them, Allen Tate

Allen Tate

John Orley Allen Tate was an American poet, essayist, social commentator, and Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1943 to 1944.-Life:...

, wrote a rebuttal of fascism for the liberal The New Republic

The New Republic

The magazine has also published two articles concerning income inequality, largely criticizing conservative economists for their attempts to deny the existence or negative effect increasing income inequality is having on the United States...

. Nevertheless, Tate remained in contact with Collins and continued to publish in The American Review until its demise, in 1937.

In addition to featuring essays by many critics of modernity

Modernity

Modernity typically refers to a post-traditional, post-medieval historical period, one marked by the move from feudalism toward capitalism, industrialization, secularization, rationalization, the nation-state and its constituent institutions and forms of surveillance...

, The American Review also became the a vehicle for spreading the ideas associated with English Distributism

Distributism

Distributism is a third-way economic philosophy formulated by such Catholic thinkers as G. K...

, the supporters of which included G. K. Chesterton

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, KC*SG was an English writer. His prolific and diverse output included philosophy, ontology, poetry, plays, journalism, public lectures and debates, literary and art criticism, biography, Christian apologetics, and fiction, including fantasy and detective fiction....

and Hilaire Belloc

Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc was an Anglo-French writer and historian who became a naturalised British subject in 1902. He was one of the most prolific writers in England during the early twentieth century. He was known as a writer, orator, poet, satirist, man of letters and political activist...

.

Collins and his wife, a spiritual medium

Mediumship

Mediumship is described as a form of communication with spirits. It is a practice in religious beliefs such as Spiritualism, Spiritism, Espiritismo, Candomblé, Voodoo and Umbanda.- Concept :...

, were actively involved with psychic phenomena

Parapsychology

The term parapsychology was coined in or around 1889 by philosopher Max Dessoir, and originates from para meaning "alongside", and psychology. The term was adopted by J.B. Rhine in the 1930s as a replacement for the term psychical research...

during the 1930s. Their circle of friends included W.H. Salter, Theodore Besterman

Theodore Besterman

Theodore Deodatus Nathaniel Besterman was a psychical researcher, bibliographer, biographer, and translator. He was the first editor of the Journal of Documentation.Besterman born in Łódź, Poland, but moved to London in his youth...

and Mrs. Henry Sidgwick, all of whom were affiliated with the Society for Psychical Research

Society for Psychical Research

The Society for Psychical Research is a non-profit organisation in the United Kingdom. Its stated purpose is to understand "events and abilities commonly described as psychic or paranormal by promoting and supporting important research in this area" and to "examine allegedly paranormal phenomena...

in London.

Today Collins is remembered primarily as a fascist editor and publisher who detested both capitalism and communism and counted many pre-War writers as his friends or colleagues. His essay "Monarch as Alternative," mentioned above, appears in Conservatism in America Since 1930, a collection of essays by conservative

American conservatism

Conservatism in the United States has played an important role in American politics since the 1950s. Historian Gregory Schneider identifies several constants in American conservatism: respect for tradition, support of republicanism, preservation of "the rule of law and the Christian religion", and...

writers published by New York University Press in 2003.

A 2005 biography of Collins, And Then They Loved Him: Seward Collins & the Chimera of an American Fascism, argues that he was never a real "fascist." This book, which is based on Collins' actual papers and letters (as well as his FBI file), argues that Collins was in fact a Distributist, i.e., a follower of G. K. Chesterton

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, KC*SG was an English writer. His prolific and diverse output included philosophy, ontology, poetry, plays, journalism, public lectures and debates, literary and art criticism, biography, Christian apologetics, and fiction, including fantasy and detective fiction....

and Hilaire Belloc

Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc was an Anglo-French writer and historian who became a naturalised British subject in 1902. He was one of the most prolific writers in England during the early twentieth century. He was known as a writer, orator, poet, satirist, man of letters and political activist...

, who inexplicably called Agrarianism

Agrarianism

Agrarianism has two common meanings. The first meaning refers to a social philosophy or political philosophy which values rural society as superior to urban society, the independent farmer as superior to the paid worker, and sees farming as a way of life that can shape the ideal social values...

"fascism." Indeed, the book concludes that Collins then became a kind of scapegoat

Scapegoat

Scapegoating is the practice of singling out any party for unmerited negative treatment or blame. Scapegoating may be conducted by individuals against individuals , individuals against groups , groups against individuals , and groups against groups Scapegoating is the practice of singling out any...

after 1941 when many other members of the American social and intellectual elites were eager to distract attention from their own flirtations with fascism in the 1920s and 1930s. Yet his praise of Hitler and Mussolini, noted above, testifies to his beliefs, at least during the 1930s.

External links

- And Then They Loved Him: Seward Collins & the Chimera of an American Fascism, Collins biography by Michael Jay Tucker