Seminole Wars

Encyclopedia

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

between the Seminole

Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people originally of Florida, who now reside primarily in that state and Oklahoma. The Seminole nation emerged in a process of ethnogenesis out of groups of Native Americans, most significantly Creeks from what is now Georgia and Alabama, who settled in Florida in...

— the collective name given to the amalgamation of various groups of native Americans

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

and Black people who settled in Florida in the early 18th century — and the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

Army. The First Seminole War was from 1814 to 1819 (although sources differ), the Second Seminole War from 1835 to 1842, and the Third Seminole War from 1855 to 1858.

The first conflict with the Seminole arose out of tensions relating to General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

's attack and destruction of Negro Fort

Fort Gadsden

Fort Gadsden is located in Franklin County, Florida, on the Apalachicola River. The site contains the ruins of two forts, and has been known by several other names at various times, including Prospect Bluff Fort, Nichol's Fort, British Post, Negro Fort, African Fort, and Fort Apalachicola.Listed...

in Florida in 1816. Jackson also attacked the Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

at Pensacola

Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle and the county seat of Escambia County, Florida, United States of America. As of the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 56,255 and as of 2009, the estimated population was 53,752...

. Ultimately, the Spanish Crown ceded the colony to United States rule.

Colonial Florida

The indigenous peoplesIndigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are ethnic groups that are defined as indigenous according to one of the various definitions of the term, there is no universally accepted definition but most of which carry connotations of being the "original inhabitants" of a territory....

of Florida declined significantly in number after the arrival of Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

ans in the region. The Native Americans

Native Americans in the United States

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples in North America within the boundaries of the present-day continental United States, parts of Alaska, and the island state of Hawaii. They are composed of numerous, distinct tribes, states, and ethnic groups, many of which survive as...

had little resistance to diseases newly introduced from Europe. Spanish suppression of native revolts further reduced the population in northern Florida. By 1707, colonial soldiers from the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina

The Province of Carolina, originally chartered in 1629, was an English and later British colony of North America. Because the original Heath charter was unrealized and was ruled invalid, a new charter was issued to a group of eight English noblemen, the Lords Proprietors, in 1663...

and their Yamasee Indian

Yamasee

The Yamasee were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans that lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida.-History:...

allies had killed or carried off nearly all the remaining native inhabitants, having conducted a series of raids extending the full length of the peninsula. In the first decade of the 18th century, 10,000 – 12,000 Indians were taken as slaves according to the governor of La Florida and by 1710, observers noted that north Florida was virtually depopulated. The few remaining natives fled west to Pensacola

Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle and the county seat of Escambia County, Florida, United States of America. As of the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 56,255 and as of 2009, the estimated population was 53,752...

and beyond or east to the vicinity of St. Augustine

St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine is a city in the northeast section of Florida and the county seat of St. Johns County, Florida, United States. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorer and admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, it is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city and port in the continental United...

; in 1763, when Spain ceded Florida to Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Paris

Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, often called the Peace of Paris, or the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763, by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement. It ended the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

, the Spanish took the few surviving Florida Indians with them to Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

and New Spain

New Spain

New Spain, formally called the Viceroyalty of New Spain , was a viceroyalty of the Spanish colonial empire, comprising primarily territories in what was known then as 'América Septentrional' or North America. Its capital was Mexico City, formerly Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztec Empire...

.

Bands from various Native American tribes from the southeastern United States

Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, colloquially referred to as the Southeast, is the eastern portion of the Southern United States. It is one of the most populous regions in the United States of America....

began moving into the unoccupied lands of Florida. In 1715, the Yamasee

Yamasee

The Yamasee were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans that lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida.-History:...

moved into Florida as allies of the Spanish, after conflicts with the English colonies. Creek people

Creek people

The Muscogee , also known as the Creek or Creeks, are a Native American people traditionally from the southeastern United States. Mvskoke is their name in traditional spelling. The modern Muscogee live primarily in Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida...

, at first primarily the Lower Creek but later including Upper Creek, also started moving into Florida from the area of Georgia. The Mikasuki, Hitchiti

Hitchiti

The Hitchiti were a Muskogean-speaking tribe formerly residing chiefly in a town of the same name on the east bank of the Chattahoochee River, 4 miles below Chiaha, in west Georgia. They spoke the Hitchiti language, which was mutually intelligible with Mikasuki; both tribes were part of the loose...

-speakers, settled around what is now Lake Miccosukee

Lake Miccosukee

Lake Miccosukee is a large swampy prairie lake in northern Jefferson County, Florida, USA, located east of the settlement of Miccosukee. A small portion of the lake, its northwest corner, is located in Leon County.-Characteristics:...

near Tallahassee

Tallahassee, Florida

Tallahassee is the capital of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County, and is the 128th largest city in the United States. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2010, the population recorded by...

. (Descendants of this group have maintained a separate tribal identity as today's Miccosukee

Miccosukee

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida are a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving federal recognition in 1962...

.)

Another group of Hitchiti speakers, led by Cowkeeper

Cowkeeper

Cowkeeper, also known as Ahaya in Mikasuki , was the first recorded chief of the Alachua band of the Seminole tribe. This was the name which the English used, as he held a very large herd of cattle.-Early life and education:...

, settled in what is now Alachua County

Alachua County, Florida

Alachua County is a county located in the U.S. state of Florida. The U.S. Census Bureau 2006 estimate for the county is 227,120. Its county seat is Gainesville, Florida. Alachua County is the home of the University of Florida and is also known for its diverse culture, local music, and artisans...

, an area where the Spanish had maintained cattle ranches in the 17th century. One of the best-known ranches was Rancho de la Chua. The region became known as the "Alachua Prairie

Paynes Prairie

Paynes Prairie is a Florida State Park, encompassing a savanna south of Gainesville, Florida, in Micanopy. It is also a U.S. National Natural Landmark. It is crossed by both I-75 and U.S. 441 .- History :...

". The Spanish in Saint Augustine began calling the Alachua Creek Cimarrones, which roughly meant "wild ones" or "runaways". This was the probable origin of the term "Seminole". This name was eventually applied to the other groups in Florida, although the Indians still regarded themselves as members of different tribes. Other Native American groups in Florida during the Seminole Wars included te Choctaw

Choctaw

The Choctaw are a Native American people originally from the Southeastern United States...

, Yuchi

Yuchi

For the Chinese surname 尉迟, see Yuchi.The Yuchi, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American Indian tribe who traditionally lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee in the 16th century. During the 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina...

or Spanish Indians, so called because it was believed that they were descended from Calusa

Calusa

The Calusa were a Native American people who lived on the coast and along the inner waterways of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region; at the time of European contact, the Calusa were the people of the Caloosahatchee culture...

s; and "rancho Indians", who lived at Spanish/Cuban fishing camps on the Florida coast.

Escaped African and African-American slaves who could reach the fort were essentially free. Many were from Pensacola; some were free citizens though others had escaped from United States territory. The Spanish offered the slaves freedom and land in Florida; they recruited former slaves as militia to help defend Pensacola and Fort Mose. Other escaped slaves joined various Seminole bands as free members of the tribe.

While most of the former slaves at Fort Mose went to Cuba with the Spanish when they left Florida in 1763, others lived with or near various bands of Indians. Slaves continued to escape from the Carolinas and Georgia and make their way to Florida. The blacks who stayed with or later joined the Seminoles became integrated into the tribes, learning the languages, adopting the dress, and inter-marrying. Some of the Black Seminoles

Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles is a term used by modern historians for the descendants of free blacks and some runaway slaves , mostly Gullahs who escaped from coastal South Carolina and Georgia rice plantations into the Spanish Florida wilderness beginning as early as the late 17th century...

, as they were called, became important tribal leaders.

Early conflict

During the American RevolutionAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, the British—who controlled Florida—recruited Seminoles to raid frontier settlements in Georgia. The confusion of war allowed more slaves to escape to Florida. The British promised slaves freedom for fighting with them. These events made the Seminoles enemies of the new United States. In 1783, as part of the treaty

Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

ending the Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

, Florida was returned to Spain. Spain's grip on Florida was light, as it maintained only small garrison

Garrison

Garrison is the collective term for a body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it, but now often simply using it as a home base....

s at St. Augustine, St. Marks

St. Marks, Florida

St. Marks is a city in Wakulla County, Florida, United States. It is part of the Tallahassee, Florida, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 272 at the 2000 census. As of 2004, the population estimated by the U.S. Census Bureau is 299 .-Geography:...

and Pensacola

Pensacola, Florida

Pensacola is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle and the county seat of Escambia County, Florida, United States of America. As of the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 56,255 and as of 2009, the estimated population was 53,752...

. They did not control the border between Florida and the United States. Mikasukis and other Seminole groups still occupied towns on the United States side of the border, while American squatters moved into Spanish Florida.

The British had divided Florida into East Florida

East Florida

East Florida was a colony of Great Britain from 1763–1783 and of Spain from 1783–1822. East Florida was established by the British colonial government in 1763; as its name implies it consisted of the eastern part of the region of Florida, with West Florida comprising the western parts. Its capital...

and West Florida

West Florida

West Florida was a region on the north shore of the Gulf of Mexico, which underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. West Florida was first established in 1763 by the British government; as its name suggests it largely consisted of the western portion of the region...

in 1763, a division retained by the Spanish when they regained Florida in 1783. West Florida extended from the Apalachicola River

Apalachicola River

The Apalachicola River is a river, approximately 112 mi long in the State of Florida. This river's large watershed, known as the ACF River Basin for short, drains an area of approximately into the Gulf of Mexico. The distance to its farthest headstream in northeast Georgia is approximately 500...

to the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

. Together with their possession of Louisiana

Louisiana (New France)

Louisiana or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682–1763 and 1800–03, the area was named in honor of Louis XIV, by French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle...

, the Spanish controlled the lower reaches of all of the rivers draining the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains #Whether the stressed vowel is or ,#Whether the "ch" is pronounced as a fricative or an affricate , and#Whether the final vowel is the monophthong or the diphthong .), often called the Appalachians, are a system of mountains in eastern North America. The Appalachians...

. It prohibited the US from transport and trade on the lower Mississippi. In addition to its desire to expand west of the mountains, the United States wanted to acquire Florida. It wanted to gain free commerce on western rivers, and to prevent Florida from being used a base for possible invasion of the U.S. by a European country.

The Louisiana Purchase

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase was the acquisition by the United States of America of of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S...

in 1803 put the mouth of the Mississippi River in US hands. But, much of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee were drained by rivers that passed through East or West Florida to reach the Gulf of Mexico. The U.S. claimed that the Louisiana Purchase had included West Florida west of the Perdido River

Perdido River

The Perdido River is a river in the U.S. states of Alabama and Florida. The river forms part of the boundary between the two states along nearly its entire length and drains into the Gulf of Mexico...

, while Spain claimed that West Florida extended to the Mississippi River.

In 1810, residents of Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge is the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is located in East Baton Rouge Parish and is the second-largest city in the state.Baton Rouge is a major industrial, petrochemical, medical, and research center of the American South...

formed a new government, seized the local Spanish fort and requested protection by the United States. President James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

authorized William C.C. Claiborne

William C.C. Claiborne

William Charles Cole Claiborne was a United States politician, best known as the first Governor of Louisiana. He also has the distinction of possibly being the youngest Congressman in U.S...

, governor of the Territory of Orleans, to seize West Florida from the Mississippi River to as far east as the Perdido River. Claiborne only occupied the area west of the Pearl River

Pearl River (Mississippi-Louisiana)

The Pearl River is a river in the U.S. states of Mississippi and Louisiana. It forms in Neshoba County, Mississippi from the confluence of Nanih Waiya and Tallahaga creeks. It is long. The Yockanookany and Strong rivers are tributaries. Northeast of Jackson, the Ross Barnett Reservoir is formed by...

(the current eastern boundary of Louisiana). Madison sent George Mathews

George Mathews (Georgia)

George Mathews was an United States planter, merchant, and pioneer from Virginia and western Georgia. He served in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War then settled in Georgia. He served as the 20th Governor of Georgia, one term in the U.S...

to deal with Florida. When an offer to turn the remainder of West Florida over to the U.S. was rescinded by the governor of West Florida, Mathews traveled to East Florida to incite a rebellion similar to that in Baton Rouge.

The residents of East Florida were happy with the status quo, so the US raised a force of volunteers in Georgia with a promise of free land. In March 1812, this force of "Patriots", with the aid of some United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

gunboat

Gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.-History:...

s, seized Fernandina

Fernandina Beach, Florida

Fernandina Beach is a city in Nassau County in the state of Florida in the United States of America and on Amelia Island. It is a part of Greater Jacksonville and is among Florida's northernmost cities. The area was first inhabited by the Timucuan Indian tribe...

. The seizure of Fernandina was authorized by President James Madison

James Madison

James Madison, Jr. was an American statesman and political theorist. He was the fourth President of the United States and is hailed as the “Father of the Constitution” for being the primary author of the United States Constitution and at first an opponent of, and then a key author of the United...

, but he later disavowed it. The Patriots were unable to take the Castillo de San Marcos

Castillo de San Marcos

The Castillo de San Marcos site is the oldest masonry fort in the United States. It is located in the city of St. Augustine, Florida. Construction was begun in 1672 by the Spanish when Florida was a Spanish territory. During the twenty year period of British possession from 1763 until 1784, the...

in St. Augustine. The increasing tensions and approach of war with Great Britain led to an end of the US incursion into East Florida. In 1813 an American force succeeded in seizing Mobile, Alabama

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile is the third most populous city in the Southern US state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County. It is located on the Mobile River and the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 195,111 during the 2010 census. It is the largest...

from the Spanish.

Before the Patriot army withdrew from Florida, the Seminole, as allies of the Spanish, began to attack them.

First Seminole War

The beginning and ending dates for the First Seminole War are not firmly established. The U.S. Army Infantry indicates that it lasted from 1814 until 1819. The U.S. Navy Naval Historical Center gives dates of 1816-1818. Another Army site dates the war as 1817-1818. Finally, the unit history of the 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery describes the war as occurring solely in 1818.Creek War and the Negro Fort

During the Creek WarCreek War

The Creek War , also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, began as a civil war within the Creek nation...

(1813-1814), Colonel Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

became a national hero after his victory over the Creek Red Sticks

Red Sticks

Red Sticks is the English term for a traditionalist faction of Creek Indians who led a resistance movement which culminated in the outbreak of the Creek War in 1813....

at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. After his victory, Jackson forced the Treaty of Fort Jackson

Treaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick resistance by United States allied forces at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. It occurred on the banks of the Tallapoosa River near the present city of Alexander City,...

on the Creek, resulting in the loss of much Creek territory in southern Georgia and central and southern Alabama. As a result, many Creek left Alabama and Georgia, and moved to Florida. The Creek refugees joined the Seminole of Florida.

Also in 1814, Britain, still at war with the United States

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

, landed forces in Pensacola and other places in West Florida. They began to recruit Indian allies. In May 1814, a British force entered the mouth of the Apalachicola River, and distributed arms to the Seminole and Creek warriors, and fugitive slaves. The British moved upriver and began building a fort at Prospect Bluff

Fort Gadsden

Fort Gadsden is located in Franklin County, Florida, on the Apalachicola River. The site contains the ruins of two forts, and has been known by several other names at various times, including Prospect Bluff Fort, Nichol's Fort, British Post, Negro Fort, African Fort, and Fort Apalachicola.Listed...

. After the British and their Indian allies were beaten back from an attack on Mobile

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile is the third most populous city in the Southern US state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County. It is located on the Mobile River and the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 195,111 during the 2010 census. It is the largest...

, a US force led by General Jackson drove the British out of Pensacola. They managed to continue work on the fort at Prospect Bluff.

When the War of 1812 ended, all the British forces left West Florida except for Major Edward Nicolls

Edward Nicolls

General Sir Edward Nicolls, KCB was an Irish officer of the Royal Marines. Known as "Fighting Nicolls", he had a distinguished career, was involved in numerous actions, and often received serious wounds. For his service, he received medals and honours, reaching the rank of General...

of the Royal Marines

Royal Marines

The Corps of Her Majesty's Royal Marines, commonly just referred to as the Royal Marines , are the marine corps and amphibious infantry of the United Kingdom and, along with the Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary, form the Naval Service...

. He directed the provisioning of Fort Gadsden

Fort Gadsden

Fort Gadsden is located in Franklin County, Florida, on the Apalachicola River. The site contains the ruins of two forts, and has been known by several other names at various times, including Prospect Bluff Fort, Nichol's Fort, British Post, Negro Fort, African Fort, and Fort Apalachicola.Listed...

with cannon, muskets and ammunition. He told the Indians that the Treaty of Ghent

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent , signed on 24 December 1814, in Ghent , was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland...

guaranteed the return of all Indian lands lost during the War of 1812, including the Creek lands in Georgia and Alabama. As the Seminole were not interested in holding a fort, they returned to their villages. Before Nicholls left in the summer of 1815, he offered Fort Gadsden to the fugitive slaves in the area. As word spread in the American Southeast about the fort, whites called it the "Negro Fort." They worried that it would inspire their slaves to escape to Florida or revolt.

José Masot

José Masot was a Spanish soldier and commander who was Governor of West Florida from 1816 - May 26, 1818. He was West Florida's governor through much of the First Seminole War, until he was deposed by American general Andrew Jackson and replaced with William King.- Biography :José Masot born...

of West Florida that if the Spanish did not eliminate the fort, he would. The governor replied that he did not have the forces to take the fort.

Jackson assigned Brigadier General Edmund Pendleton Gaines

Edmund P. Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines was a United States army officer who served with distinction during the War of 1812, the Seminole Wars and the Black Hawk War.-Early life:...

to take control of the fort. Gaines directed Colonel Duncan Lamont Clinch

Duncan Lamont Clinch

Duncan Lamont Clinch was an American army officer and served as a commander during the First and Second Seminole Wars. He also served in the United States House of Representatives, representing Georgia....

to build Fort Scott on the Flint River

Flint River (Georgia)

The Flint River is a river in the U.S. state of Georgia. The river drains of western Georgia, flowing south from the upper Piedmont region south of Atlanta to the wetlands of the Gulf Coastal Plain in the southwestern corner of the state. Along with the Apalachicola and the Chattahoochee rivers,...

just north of the Florida border. Gaines said he intended to supply Fort Scott from New Orleans via the Apalachicola River. As this would mean passing through Spanish territory and past the Negro Fort, it would allow the U.S. Army to keep an eye on the Seminole and the Negro Fort. If the fort fired on the supply boats, the Americans would have an excuse to destroy it.

In July 1816, a supply fleet for Fort Scott reached the Apalachicola River. Clinch took a force of more than 100 American soldiers and about 150 Lower Creek warriors, including the chief Tustunnugee Hutkee (White Warrior), to protect their passage. The supply fleet met Clinch at the Negro Fort, and its two gunboats took positions across the river from the fort. The blacks in the fort fired their cannon at the U.S. soldiers and the Creek, but had no training in aiming the weapon. The Americans fired back. The gunboats' ninth shot, a "hot shot" (a cannon ball heated to a red glow), landed in the fort's powder magazine

Magazine

Magazines, periodicals, glossies or serials are publications, generally published on a regular schedule, containing a variety of articles. They are generally financed by advertising, by a purchase price, by pre-paid magazine subscriptions, or all three...

. The explosion leveled the fort and was heard more than 100 miles (160 km) away in Pensacola. Of the 320 people known to be in the fort, including women and children, more than 250 died instantly, and many more died from their injuries soon after. Once the US Army destroyed the fort, it withdrew from Spanish Florida.

American squatters and outlaws raided the Seminole, killing villagers and stealing their cattle. Their resentment grew and the Seminole retaliated by stealing back the cattle. On February 24, 1817, a raiding party killed Mrs. Garrett, a woman living in Camden County, Georgia

Camden County, Georgia

Camden County is a county located in the U.S. state of Georgia. It is one of the original counties of Georgia, created February 5, 1777. As of 2000, the population was 43,664. The 2007 Census Estimate shows a population of 48,689. The county seat is Woodbine.-History:The first European to land...

, and her two young children.

Fowltown and the Scott Massacre

Fowltown was a Mikasuki village in southwestern Georgia, about 15 miles (24 km) east of Fort Scott. Chief Neamathla of Fowltown got into a dispute with the commander of Fort Scott over the use of land on the eastern side of the Flint River, essentially claiming Mikasuki sovereignty over the area. The land in southern Georgia had been ceded by the Creeks in the Treaty of Fort Jackson, but the Mikasukis did not consider themselves Creek, did not feel bound by the treaty, and did not accept that the Creeks had any right to cede Mikasuki land. In November 1817, General Gaines sent a force of 250 men to seize Neamathla. The first attempt was beaten off by the Mikasukis. The next day, November 22, 1817, the Mikasukis were driven from their village. Some historians date the start of the war to this attack on Fowltown. David Brydie MitchellDavid Brydie Mitchell

David Brydie Mitchell was an American politician.-Early life:Mitchell was born in Muthill, Perthshire, Scotland on October 22, 1766 and moved to Savannah to settle the affairs of his late uncle...

, former governor of Georgia and Creek Indian agent

Indian agent

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with Native American tribes on behalf of the U.S. government.-Indian agents:*Leander Clark was agent for the Sac and Fox in Iowa beginning in 1866....

at the time, stated in a report to Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

that the attack on Fowltown was the start of the First Seminole War.

A week later a boat carrying supplies for Fort Scott, under the command of Lt. R. W. Scott, was attacked on the Apalachicola River. There were forty to fifty people on the boat, including twenty sick soldiers, seven wives of soldiers, and possibly some children. (While there are reports of four children being killed by the Seminoles, they were not mentioned in early reports of the massacre, and their presence has not been confirmed.) Most of the boat's passengers were killed by the Indians. One woman was taken prisoner, and six survivors made it to the fort.

General Gaines had been under orders not to invade Florida, later amended to allow short intrusions into Florida. When news of the Scott Massacre on the Apalachicola reached Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, Gaines was ordered to invade Florida and pursue the Indians but not to attack any Spanish installations. However, Gaines had left for East Florida to deal with pirates who had occupied Fernandina. Secretary of War

United States Secretary of War

The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation...

John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun

John Caldwell Calhoun was a leading politician and political theorist from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun eloquently spoke out on every issue of his day, but often changed positions. Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, modernizer, and proponent...

then ordered Andrew Jackson to lead the invasion of Florida.

Jackson invades Florida

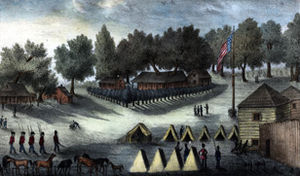

Jackson gathered his forces at Fort Scott in March 1818, including 800 U.S. Army regularsRegular Army

The Regular Army of the United States was and is the successor to the Continental Army as the country's permanent, professional military establishment. Even in modern times the professional core of the United States Army continues to be called the Regular Army...

, 1,000 Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

volunteers, 1,000 Georgia militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

, and about 1,400 friendly Lower Creek warriors. On March 15, Jackson's army entered Florida, marching down the Apalachicola River. When they reached the site of the Negro Fort, Jackson had his men construct a new fort, Fort Gadsden

Fort Gadsden

Fort Gadsden is located in Franklin County, Florida, on the Apalachicola River. The site contains the ruins of two forts, and has been known by several other names at various times, including Prospect Bluff Fort, Nichol's Fort, British Post, Negro Fort, African Fort, and Fort Apalachicola.Listed...

. The army then set out for the Mikasuki villages around Lake Miccosukee. The Indian town of Tallahassee

Tallahassee, Florida

Tallahassee is the capital of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County, and is the 128th largest city in the United States. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2010, the population recorded by...

was burned on March 31, and the town of Miccosukee

Miccosukee, Florida

Miccosukee is a historical small unincorporated community in northeastern Leon County, Florida, United States. It is located at the junction of County Road 59 and County Road 151...

was taken the next day. More than 300 Indian homes were destroyed. Jackson then turned south, reaching St. Marks on April 6.

At St. Marks Jackson seized the Spanish fort. There he found Alexander George Arbuthnot

Alexander George Arbuthnot

The Arbuthnot and Ambrister incident occurred in 1818 during the First Seminole War when American General Andrew Jackson invaded Spanish Florida and captured and executed two British subjects charged with aiding Seminole and Creek Indians against the United States...

, a Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

trader working out of the Bahamas. He traded with the Indians in Florida and had written letters to British and American officials on behalf of the Indians. He was rumored to be selling guns to the Indians and to be preparing them for war. He probably was selling guns, since the main trade item of the Indians was deer skins, and they needed guns to hunt the deer. Two Indian leaders, Josiah Francis, a Red Stick Creek, also known as the "Prophet" (not to be confused with Tenskwatawa

Tenskwatawa

Tenskwatawa, was a Native American religious and political leader of the Shawnee tribe, known as The Prophet or the Shawnee Prophet. He was the brother of Tecumseh, leader of the Shawnee...

), and Homathlemico, had been captured when they had gone out to an American ship flying the British Union Flag

Union Flag

The Union Flag, also known as the Union Jack, is the flag of the United Kingdom. It retains an official or semi-official status in some Commonwealth Realms; for example, it is known as the Royal Union Flag in Canada. It is also used as an official flag in some of the smaller British overseas...

that had anchored off of St. Marks. As soon as Jackson arrived at St. Marks, the two Indians were brought ashore and hanged.

Jackson left St. Marks to attack villages along the Suwannee River

Suwannee River

The Suwannee River is a major river of southern Georgia and northern Florida in the United States. It is a wild blackwater river, about long. The Suwannee River is the site of the prehistoric Suwannee Straits which separated peninsular Florida from the panhandle.-Geography:The river rises in the...

, which were occupied primarily by fugitive slaves. On April 12, the army found a Red Stick village on the Econfina River

Econfina River

The Econfina River is a minor river draining part of the Big Bend region of Florida, U.S.A. into Apalachee Bay. The river rises in San Pedro Bay near the boundary between Madison and Taylor counties, and flows through Taylor County to Apalachee Bay. It has a watershed of .- References :* Marth,...

. Close to 40 Red Sticks were killed, and about 100 women and children were captured. In the village, they found Elizabeth Stewart, the woman who had been captured in the attack on the supply boat on the Apalachicola River the previous November. Harassed by Black Seminoles along the route, the army found the villages on the Suwannee empty. About this time, Robert Ambrister, a former Royal Marine and self-appointed British "agent", was captured by Jackson's army. Having destroyed the major Seminole and black villages, Jackson declared victory and sent the Georgia Militia and the Lower Creeks home. The remaining army then returned to St. Marks.

Military tribunal

A military tribunal is a kind of military court designed to try members of enemy forces during wartime, operating outside the scope of conventional criminal and civil proceedings. The judges are military officers and fulfill the role of jurors...

was convened, and Ambrister and Arbuthnot were charged with aiding the Seminoles and the Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, inciting them to war and leading them against the United States. Ambrister threw himself on the mercy of the court, while Arbuthnot maintained his innocence, saying that he had only been engaged in legal trade. The tribunal sentenced both men to death but then relented and changed Ambrister's sentence to fifty lashes and a year at hard labor. Jackson, however, reinstated Ambrister's death penalty. Ambrister was executed by a firing squad on April 29, 1818. Arbuthnot was hanged from the yardarm

Yard (sailing)

A yard is a spar on a mast from which sails are set. It may be constructed of timber, steel, or from more modern materials, like aluminium or carbon fibre. Although some types of fore and aft rigs have yards , the term is usually used to describe the horizontal spars used with square sails...

of his own ship.

Jackson left a garrison at St. Marks and returned to Ft. Gadsden. Jackson had first reported that all was peaceful and that he would be returning to Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat of Davidson County. It is located on the Cumberland River in Davidson County, in the north-central part of the state. The city is a center for the health care, publishing, banking and transportation industries, and is home...

. He later reported that Indians were gathering and being supplied by the Spanish, and he left Fort Gadsden with 1,000 men on May 7, headed for Pensacola. The governor of West Florida protested that most of the Indians at Pensacola were women and children and that the men were unarmed, but Jackson did not stop. When Jackson reached Pensacola on May 23, the governor and the 175-man Spanish garrison retreated to Fort Barrancas

Fort Barrancas

Fort Barrancas or Fort San Carlos de Barrancas is a historic United States military fort in the Warrington area of Pensacola, Florida, located physically on Naval Air Station Pensacola....

, leaving the city of Pensacola to Jackson. The two sides exchanged cannon fire for a couple of days, and then the Spanish surrendered Fort Barrancas on May 28. Jackson left Colonel William King as military governor of West Florida and went home.

Consequences

There were international repercussions to Jackson's actions. Secretary of StateUnited States Department of State

The United States Department of State , is the United States federal executive department responsible for international relations of the United States, equivalent to the foreign ministries of other countries...

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States . He served as an American diplomat, Senator, and Congressional representative. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of former...

had just started negotiations with Spain for the purchase of Florida. Spain protested the invasion and seizure of West Florida and suspended the negotiations. Spain did not have the means to retaliate against the United States or regain West Florida by force, so Adams let the Spanish protest, then issued a letter (with 72 supporting documents) blaming the war on the British, Spanish, and Indians. In the letter he also apologized for the seizure of West Florida, said that it had not been American policy to seize Spanish territory, and offered to give St. Marks and Pensacola back to Spain. Spain accepted and eventually resumed negotiations for the sale of Florida. Defending Jackson's actions as necessary, and sensing that they strengthened his diplomatic standing, Adams demanded Spain either control the inhabitants of East Florida or cede it to the United States. An agreement was then reached whereby Spain ceded East Florida to the United States and renounced all claim to West.

Adams-Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty or the Purchase of Florida, was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that gave Florida to the U.S. and set out a boundary between the U.S. and New Spain . It settled a standing border dispute between the two...

Britain protested the execution of two of its subjects who had never entered United States territory. There was talk in Britain of demanding reparations and taking reprisals. Americans worried about another war with Britain. In the end Britain, realizing how important the United States was to its economy, opted for maintaining good relations.

There were also repercussions in America. Congressional committees held hearings into the irregularities of the Ambrister and Arbuthnot trials. While most Americans supported Jackson, some worried that Jackson could become a "man on horseback", a Napoleon

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

. When Congress reconvened in December 1818, resolutions were introduced condemning Jackson's actions. Jackson was too popular, and the resolutions failed, but the Ambrister and Arbuthnot executions left a stain on his reputation for the rest of his life, even if it was not enough to keep him from becoming president.

First Interbellum

Spain did cede FloridaAdams-Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty or the Purchase of Florida, was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that gave Florida to the U.S. and set out a boundary between the U.S. and New Spain . It settled a standing border dispute between the two...

, and the United States took possession in 1821. Effective government was slow in coming to Florida. General Andrew Jackson was appointed military governor of Florida in March 1821, but he did not arrive in Pensacola until July 1821. He resigned the post in September 1821 and returned home in October, having spent just three months in Florida. His successor, William P. DuVal

William Pope Duval

William Pope Duval was the first civilian governor of Florida Territory, serving from April 17, 1822 until April 24, 1834.-Early life:...

, was not appointed until April 1822, and he left for an extended visit to his home in Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

before the end of the year. Other official positions in the territory had similar turn-over and absences.

The Seminoles were still a problem for the new government. In early 1822, Capt. John R. Bell, provisional secretary of the Florida territory and temporary agent to the Seminoles, prepared an estimate of the number of Indians in Florida. He reported about 22,000 Indians, and 5,000 slaves held by Indians. He estimated that two-thirds of them were refugees from the Creek War

Creek War

The Creek War , also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, began as a civil war within the Creek nation...

, with no valid claim (in the U.S. view) to Florida. Indian settlements were located in the areas around the Apalachicola River, along the Suwannee River

Suwannee River

The Suwannee River is a major river of southern Georgia and northern Florida in the United States. It is a wild blackwater river, about long. The Suwannee River is the site of the prehistoric Suwannee Straits which separated peninsular Florida from the panhandle.-Geography:The river rises in the...

, from there south-eastwards to the Alachua Prairie, and then south-westward to a little north of Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and estuary along the Gulf of Mexico on the west central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay."Tampa Bay" is not the name of any municipality...

.

Officials in Florida were concerned from the beginning about the situation with the Seminoles. Until a treaty was signed establishing a reservation, the Indians were not sure of where they could plant crops and expect to be able to harvest them, and they had to contend with white squatters moving into land they occupied. There was no system for licensing traders, and unlicensed traders were supplying the Seminoles with liquor

Distilled beverage

A distilled beverage, liquor, or spirit is an alcoholic beverage containing ethanol that is produced by distilling ethanol produced by means of fermenting grain, fruit, or vegetables...

. However, because of the part-time presence and frequent turnover of territorial officials, meetings with the Seminoles are canceled, postponed, or sometimes held merely to set a time and place for a new meeting.

Treaty of Moultrie Creek

Acre

The acre is a unit of area in a number of different systems, including the imperial and U.S. customary systems. The most commonly used acres today are the international acre and, in the United States, the survey acre. The most common use of the acre is to measure tracts of land.The acre is related...

s (16,000 km²). The reservation would run down the middle of the Florida peninsula from just north of present-day Ocala

Ocala, Florida

Ocala is a city in Marion County, Florida. As of 2007, the population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau was 53,491. It is the county seat of Marion County, and the principal city of the Ocala, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area, which had an estimated 2007 population of 324,857.-History:Ocala...

to a line even with the southern end of Tampa Bay. The boundaries were well inland from both coasts, to prevent contact with traders from Cuba

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

and the Bahamas. Neamathla and five other chiefs were allowed to keep their villages along the Apalachicola River

Apalachicola River

The Apalachicola River is a river, approximately 112 mi long in the State of Florida. This river's large watershed, known as the ACF River Basin for short, drains an area of approximately into the Gulf of Mexico. The distance to its farthest headstream in northeast Georgia is approximately 500...

.

Under the Treaty of Moultrie Creek

Treaty of Moultrie Creek

The Treaty of Moultrie Creek was an agreement signed in 1823 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the present-day state of Florida. The United States had acquired Florida from Spain in 1821 by means of the Adams-Onís Treaty. In 1823 the...

, the US was obligated to protect the Seminole as long as they remained law-abiding. The government was supposed to distribute farm implements, cattle and hogs to the Seminole, compensate them for travel and losses involved in relocating to the reservation, and provide rations for a year, until the Seminoles could plant and harvest new crops. The government was also supposed to pay the tribe US$5,000 per year for twenty years and provide an interpreter, a school and a blacksmith for twenty years. In turn, the Seminole had to allow roads to be built across the reservation and had to apprehend and return to US jurisdiction any runaway slaves or other fugitives.

Fort Brooke

Fort Brooke was a historical military post situated on the east bank of the Hillsborough River in present-day Tampa, Florida. The Tampa Convention Center currently stands at the site.-Fort Brooke as a military outpost:...

, with four companies of infantry, was established on the site of present-day Tampa

Tampa, Florida

Tampa is a city in the U.S. state of Florida. It serves as the county seat for Hillsborough County. Tampa is located on the west coast of Florida. The population of Tampa in 2010 was 335,709....

in early 1824, to show the Seminole that the government was serious about moving them onto the reservation. However, by June James Gadsden

James Gadsden

James Gadsden was an American diplomat, soldier and businessman and namesake of the Gadsden Purchase, in which the United States purchased from Mexico the land that became the southern portion of Arizona and New Mexico. James Gadsden served as Adjutant General of the U. S...

, who was the principal author of the treaty and charged with implementing it, was reporting that the Seminole were unhappy with the treaty and were hoping to renegotiate it. Fear of a new war crept in. In July, Governor DuVal mobilized the militia and ordered the Tallahassee and Mikasukee chiefs to meet him in St. Marks. At that meeting, he ordered the Seminole to move to the reservation by October 1, 1824.

The move had not begun, but DuVal began paying the Seminole compensation for the improvements they were having to leave as an incentive to move. He also had the promised rations sent to Fort Brooke on Tampa Bay for distribution. The Seminole finally began moving onto the reservation, but within a year some returned to their former homes between the Suwannee and Apalachicola rivers. By 1826, most of the Seminole had gone to the reservation, but were not thriving. They had to clear and plant new fields, and cultivated fields suffered in a long drought. Some of the tribe were reported to have starved to death. Both Col. George M. Brooke, commander of Fort Brooke, and Governor DuVal wrote to Washington

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

seeking help for the starving Seminole, but the requests got caught up in a debate over whether the people should be moved to west of the Mississippi River. For five months, no additional relief reached the Seminole.

Fort King

Fort King was a United States military fort in north central Florida. It was named after Colonel William King, commander of Florida's Fourth Infantry and the first governor of the provisional West Florida region. The fort was built in 1827, and became the genesis of the city of Ocala...

was built near the reservation agency, at the site of present-day Ocala, and by early 1827 the Army could report that the Seminoles were on the reservation and Florida was peaceful. During the five-year peace, some settlers continued to call for removal. The Seminole were opposed to any such move, and especially to the suggestion that they join their Creek

Creek

Creek may refer to:*Creek, a small stream* Creek , an inlet of the sea, narrower than a cove * Creek, a narrow channel/small stream between islands in the Florida Keys*Muscogee , a native American people...

relations. Most whites regarded the Seminole as simply Creeks who had recently moved to Florida, while the Seminole claimed Florida as their home and denied that they had any connection with the Creeks.

The Seminole and slave catchers argued over the ownership of slaves. New plantations in Florida increased the pool of slaves who could escape to Seminole territory. Worried about the possibility of an Indian uprising and/or a slave rebellion, Governor DuVal requested additional Federal troops for Florida, but in 1828 the US closed Fort King. Short of food and finding the hunting declining on the reservation, the Seminole wandered off to get food. In 1828, Andrew Jackson, the old enemy of the Seminoles, was elected President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act

Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830.The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the Five Civilized Tribes. In particular, Georgia, the largest state at that time, was involved in...

he promoted, which was to resolve the problems by moving the Seminole and other tribes west of the Mississippi.

Treaty of Payne's Landing

In the spring of 1832, the Seminoles on the reservation were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the Oklawaha River. The treaty negotiated there called for the Seminoles to move west, if the land were found to be suitable. They were to settle on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek tribe. The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did not leave Florida until October 1832. After touring the area for several months and conferring with the Creeks who had already been settled there, the seven chiefs signed a statement on March 28, 1833, that the new land was acceptable. Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or that they had been forced to sign it, and in any case, that they did not have the power to decide for all the tribes and bands that resided on the reservation. The villages in the area of the Apalachicola River were more easily persuaded, however, and went west in 1834.

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

finally ratified the Treaty of Payne's Landing

Treaty of Payne's Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the present-day state of Florida.- Background :...

in April 1834. The treaty had given the Seminoles three years to move west of the Mississippi. The government interpreted the three years as starting 1832 and expected the Seminoles to move in 1835. Fort King was reopened in 1834. A new Seminole agent, Wiley Thompson, had been appointed in 1834, and the task of persuading the Seminoles to move fell to him. He called the chiefs together at Fort King in October 1834 to talk to them about the removal to the west. The Seminoles informed Thompson that they had no intention of moving and that they did not feel bound by the Treaty of Payne's Landing. Thompson then requested reinforcements for Fort King and Fort Brooke, reporting that, "the Indians after they had received the Annuity, purchased an unusually large quantity of Powder & Lead." General Clinch also warned Washington that the Seminoles did not intend to move and that more troops would be needed to force them to move. In March 1835, Thompson called the chiefs together to read a letter from Andrew Jackson to them. In his letter, Jackson said, "Should you ... refuse to move, I have then directed the Commanding officer to remove you by force." The chiefs asked for thirty days to respond. A month later, the Seminole chiefs told Thompson that they would not move west. Thompson and the chiefs began arguing, and General Clinch had to intervene to prevent bloodshed. Eventually, eight of the chiefs agreed to move west but asked to delay the move until the end of the year, and Thompson and Clinch agreed.

Five of the most important of the Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy

Micanopy

Micanopy , also known as Micco-Nuppe, Michenopah, Miccanopa, Mico-an-opa and Sint-chakkee , was the leading chief of the Seminoles who led the tribe during the Second Seminole War...

of the Alachua Seminoles, had not agreed to the move. In retaliation, Thompson declared that those chiefs were removed from their positions. As relations with the Seminoles deteriorated, Thompson forbid the sale of guns and ammunition to the Seminoles. Osceola

Osceola

Osceola, also known as Billy Powell , became an influential leader with the Seminole in Florida. He was of Creek, Scots-Irish and English parentage, and had migrated to Florida with his mother after the defeat of the Creek in 1814.Osceola led a small band of warriors in the Seminole resistance...

, a young warrior beginning to be noticed by the whites, was particularly upset by the ban, feeling that it equated Seminoles with slaves and said, "The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red with blood; and then blacken him in the sun and rain ... and the buzzard live upon his flesh." In spite of this, Thompson considered Osceola to be a friend and gave him a rifle. Later, though, when Osceola was causing trouble, Thompson had him locked up at Fort King for a night. The next day, in order to secure his release, Osceola agreed to abide by the Treaty of Payne's Landing and to bring his followers in.

The situation grew worse. On June 19, 1835, a group of whites searching for lost cattle found a group of Indians sitting around a campfire cooking the remains of what they claimed was one of their herd. The whites disarmed and proceeded to whip the Indians, when two more arrived and opened fire on the whites. Three whites were wounded and one Indian was killed and one wounded, at what became known as the skirmish at Hickory Sink. After complaining to Indian Agent Thompson and not receiving a satisfactory response, the Seminoles became further convinced that they would not receive fair compensations for their complaints of hostile treatment by the settlers. Believed to be in response for the incident at Hickory Sink, in August 1835, Private Kinsley Dalton (for whom Dalton, Georgia

Dalton, Georgia

Dalton is a city in Whitfield County, Georgia, United States. It is the county seat of Whitfield County and the principal city of the Dalton, Georgia Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of both Murray and Whitfield counties. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 33,128...

, is named) was killed by Seminoles as he was carrying the mail from Fort Brooke to Fort King.

In November 1835 Chief Charley Emathla, wanting no part of a war, agreed to removal and sold his cattle at Fort King in preparation for moving his people to Fort Brooke to emigrate to the west. This act was considered a betrayal by other Seminoles who months earlier declared in council that any Seminole chief who sold his cattle would be sentenced to death. Osceola met Charley Emathla on the trail back to his village and killed him, scattering the money from the cattle purchase across his body.

Second Seminole War

As Florida officials realized the Seminole would resist relocation, preparations for war began. Settlers fled to safety as Seminole attacked plantations and a militia wagon train. Two companies, totaling 110 men under the command of Major Francis L. DadeFrancis L. Dade

Francis Langhorne Dade was a Major in the U.S. 4th Infantry Regiment, United States Army, during the Second Seminole War. Dade was killed in a battle with Seminole Indians that came to be known as the "Dade Massacre"...

, were sent from Fort Brooke to reinforce Fort King. On December 28, 1835, Seminoles ambushed the soldiers and destroyed the command. Only two soldiers survived to return to Fort Brooke, and one died of his wounds a few days later. Over the next few months Generals Clinch

Duncan Lamont Clinch

Duncan Lamont Clinch was an American army officer and served as a commander during the First and Second Seminole Wars. He also served in the United States House of Representatives, representing Georgia....

, Gaines

Edmund P. Gaines

Edmund Pendleton Gaines was a United States army officer who served with distinction during the War of 1812, the Seminole Wars and the Black Hawk War.-Early life:...

and Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig Party in 1852....

, as well as territorial governor Richard Keith Call, led large numbers of troops in futile pursuits of the Seminoles. In the meantime the Seminoles struck throughout the state, attacking isolated farms, settlements, plantations and Army forts, even burning the Cape Florida lighthouse

Cape Florida Light

The Cape Florida Light is a lighthouse on Cape Florida at the south end of Key Biscayne in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It was built in 1825 and operated, with interruptions, until 1878, when it was replaced by the Fowey Rocks lighthouse. The lighthouse was put back into use in 1978...

. Supply problems and a high rate of illness during the summer caused the Army to abandon several forts.

Bulow Plantation Ruins Historic State Park

Bulow Plantation Ruins State Historic Park is a Florida State Park in Flagler Beach, Florida. It is three miles west of Flagler Beach on CR 2001, south of SR 100, and contains the ruins of an ante-bellum plantation. The original plantation was begun in 1821, growing indigo, cotton, rice, and sugar...

and fortified it with cotton bales and a stockade. Local planters took refuge with their slaves. The Major abandoned the site on January 23, 1836, and the Bulow Plantation

Bulow Plantation Ruins Historic State Park

Bulow Plantation Ruins State Historic Park is a Florida State Park in Flagler Beach, Florida. It is three miles west of Flagler Beach on CR 2001, south of SR 100, and contains the ruins of an ante-bellum plantation. The original plantation was begun in 1821, growing indigo, cotton, rice, and sugar...

was later burned by the Seminoles. Now a State Park, the site remains a window into the destruction of the conflict; the massive stone ruins of the huge Bulow sugar mill stand little changed from the 1830s. By February 1836 the Seminole and black allies had attacked 21 plantations along the river.

Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock

Ethan A. Hitchcock (general)

Ethan Allen Hitchcock was a career United States Army officer and author who had War Department assignments in Washington, D.C., during the American Civil War, in which he served as a major general.-Early life:...

was among those who found the remains of the Dade party in February. In his journal he wrote of the discovery and expressed his discontent:

"The government is in the wrong, and this is the chief cause of the persevering opposition of the Indians, who have nobly defended their country against our attempt to enforce a fraudulent treaty. The natives used every means to avoid a war, but were forced into it by the tyranny of our government."

On November 21, 1836 at the Battle of Wahoo Swamp

Battle of Wahoo Swamp

The Battle of Wahoo Swamp was fought during the Second Seminole War. An army of militia, Tennessee volunteers, Creek mercenaries and United States marines and soldiers led by Florida Governor, General Richard K...

, the Seminole fought against American allied forces; among the US dead was David Moniac

David Moniac

David Moniac, born December 25th, 1802, died 1836, was a Creek Indian of mixed ancestry, a grand-nephew of Alexander McGillivray.He was the first cadet appointed from Alabama and in 1822 became the first Native American, and first non-white man, to graduate from West Point. He was the only Native...

, the first Native American graduate of West Point. The skirmish restored Seminole confidence, showing their ability to hold their ground against their old enemies the Creek and white settlers.

Late in 1836, Major General Thomas Jesup

Thomas Jesup

Brigadier General Thomas Sidney Jesup, USA was an American military officer known as the "Father of the Modern Quartermaster Corps". He was born in Berkeley County, West Virginia. He began his military career in 1808, and served in the War of 1812, seeing action in the battles of Chippewa and...

, US Quartermaster, was placed in command of the war. Jesup brought a new approach to the war. He concentrated on wearing the Seminole down rather than sending out large groups who were more easily ambushed. He needed a large military presence in the state to cover it, and he eventually had a force of more than 9,000 men under his command. About half of the force were volunteers and militia. It also included a brigade of marines, and Navy and Revenue-Marine

United States Revenue Cutter Service

The United States Revenue Cutter Service was established by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton in 1790 as an armed maritime law enforcement service. Throughout its entire existence the Revenue Cutter Service operated under the authority of the United States Department of the Treasury...

personnel patrolling the coast and inland rivers and streams.

Ar-pi-uck-i (Sam Jones)

Ar-pi-uck-i, also known as Sam Jones, was a powerful spiritual alektca and war chief of the Miccosukee, a Seminole-Muscogee Creek tribe of the Southeast United States. Ar-pi-uck-i successfully defied the U.S...

(a.k.a. Abiaca, Ar-pi-uck-i, Opoica, Arpeika, Aripeka, Aripeika), had not surrendered, however, and were known to be vehemently opposed to relocation. On June 2 these two leaders with about 200 followers entered the poorly guarded holding camp at Fort Brooke and led away the 700 Seminole who had surrendered. The war was on again, and Jesup decided against trusting the word of an Indian. On Jesup's orders, Brigadier General Joseph Marion Hernández

Joseph Marion Hernández

José Mariano Hernández or Joseph Marion Hernández was an American politician, plantation owner, and soldier. He was the first from the Florida Territory and the first Hispanic American to serve in the United States Congress. He served from September 1822 to March 1823. He was a member of the Whig...

commanded the expedition that captured several Indian leaders, including Coacoochee

Wild Cat (Seminole)

Wild Cat, born Coacoochee or Cowacoochee , was a leading Seminole chieftain during the later stages of the Second Seminole War as well as the nephew of Micanopy....

(Wild Cat), John Horse, Osceola and Micanopy when they appeared for conferences under a white flag

White flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.-Flag of temporary truce in order to parley :...

of truce. Coacoochee and other captives, including John Horse, escaped from their cell at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, but Osceola did not go with them. He died in prison, probably of malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

.

Jesup organized a sweep down the peninsula with multiple columns, pushing the Seminole further south. On Christmas Day 1837, Colonel Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass...

's column of 800 men encountered a body of about 400 warriors on the north shore of Lake Okeechobee

Lake Okeechobee

Lake Okeechobee , locally referred to as The Lake or The Big O, is the largest freshwater lake in the state of Florida. It is the seventh largest freshwater lake in the United States and the second largest freshwater lake contained entirely within the lower 48 states...

. The Seminole were led by Sam Jones, Alligator and the recently escaped Coacoochee; they were well positioned in a hammock

Hammock (ecology)

Hammocks are dense stands of hardwood trees that grow on natural rises of only a few inches higher than surrounding marshland that is otherwise too wet to support them. Hammocks are distinctive in that they are formed gradually over thousands of years rising in a wet area through the deposits of...

surrounded by sawgrass

Cladium

Cladium is a genus of large sedges, with a worldwide distribution in tropical and temperate regions...

. Taylor's army came up to a large hammock with half a mile of swamp in front of it. On the far side of the hammock was Lake Okeechobee. Here the saw grass stood five feet high. The mud and water were three feet deep. Horses would be of no use. The Seminole had chosen their battleground. They had sliced the grass to provide an open field of fire and had notched the trees to steady their rifles. Their scouts were perched in the treetops to follow every movement of the troops coming up.

At about half past noon, with the sun shining directly overhead and the air still and quiet, Taylor moved his troops squarely into the center of the swamp. His plan was to attack directly rather than try to encircle the Indians. All his men were on foot. In the first line were the Missouri volunteers. As soon as they came within range, the Seminole opened with heavy fire. The volunteers broke, and their commander Colonel Gentry, fatally wounded, was unable to rally them. They fled back across the swamp. The fighting in the saw grass was deadliest for five companies of the Sixth Infantry; every officer but one, and most of their noncoms, were killed or wounded. When those units retired a short distance to re-form, they found only four men of these companies unharmed. The US eventually drove the Seminole from the hammock, but they escaped across the lake. Taylor lost 26 killed and 112 wounded, while the Seminole casualties were eleven dead and fourteen wounded. The US claimed the Battle of Lake Okeechobee

Battle of Lake Okeechobee

The Battle of Lake Okeechobee was one of the major battles of the Second Seminole War. It was fought between 800 troops of the 1st, 4th, and 6th Infantry Regiments and 132 Missouri Volunteers and between 380 and 480 Seminoles led by Billy Bowlegs, Abiaca and Alligator on December 25, 1837...

as a great victory.

At the end of January, Jesup's troops caught up with a large body of Seminole to the east of Lake Okeechobee. Originally positioned in a hammock, the Seminole were driven across a wide stream by cannon and rocket fire, and made another stand. They faded away, having inflicted more casualties than they suffered, and the Battle of Loxahatchee was over. In February 1838, the Seminole chiefs Tuskegee and Halleck Hadjo approached Jesup with the proposal to stop fighting if they could stay south of Lake Okeechobee. Jesup favored the idea but had to gain approval from officials in Washington for approval. The chiefs and their followers camped near the Army while awaiting the reply. When the secretary of war rejected the idea, Jesup seized the 500 Indians in the camp, and had them transported to Indian Territory.

In May, Jesup's request to be relieved of command was granted, and Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor