Scotland in the Late Middle Ages

Encyclopedia

Scotland in the late Middle Ages established its independence from England under figures including William Wallace

in the late 13th century and Robert Bruce

in the 14th century. In the 15th century under the Stewart Dynasty, despite a turbulent political history, the crown gained greater political control at the expense of independent lords and restored most of its lost territory to approximately the modern borders of the country. However, the Auld Alliance

with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 and the death of the king James IV

, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability.

The economy of Scotland developed slowly in this period and population of perhaps a million by the middle of the 14th century began to decline after the arrival of the Black Death

, falling to perhaps half a million by the beginning of the 16th century. Different social systems and cultures developed in the lowland and highland regions of the country as Gaelic remained the most common language north of the Tay

and Middle Scots

dominated in the south, where it became the language of the ruling elite, government and a new national literature. There were significant changes in religion which saw mendicant

friars and new devotions expand, particularly in the developing burgh

s.

By the end of the period Scotland had adopted many of the major tenants of the European Renaissance in art, architecture and literature and produced a developed educational system. This period has been seen as seeing a clear national identity emerge in Scotland as well as significant distinctions between different regions of the country which would be particularly significant in the period of the Reformation.

in 1286, and the subsequent death of his granddaughter and heir Margaret

(called "the Maid of Norway") in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked Edward I of England

to arbitrate, for which he extracted legal recognition that the realm of Scotland was held as a feudal dependency to the throne of England before choosing John Balliol, the man with the strongest claim, who became king as John I (30 November 1292). Robert Bruce of Annandale, the next strongest claimant, accepted this outcome with reluctance. Over the next few years Edward I used the concessions he had gained to systematically undermine both the authority of King John and the independence of Scotland. In 1295 John, on the urgings of his chief councillors, entered into an alliance with France, the beginning of the Auld Alliance

.

In 1296 Edward invaded Scotland, deposing King John. The following year William Wallace

and Andrew de Moray raised forces to resist the occupation and under their joint leadership an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge

. For a short time Wallace ruled Scotland in the name of John Balliol as Guardian

of the realm. Edward came north in person and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk (1298)

. Wallace escaped but probably resigned as Guardian of Scotland. In 1305 he fell into the hands of the English, who executed him for treason despite the fact that he owed no allegiance to England.

Rivals John Comyn

Rivals John Comyn

and Robert the Bruce

, grandson of the claimant, were appointed as joint guardians in his place. On 10 February 1306, Bruce participated in the murder of Comyn, at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries

. Less than seven weeks later, on March 25, Bruce was crowned as King. However, Edward's forces overran the country after defeating Bruce's small army at the Battle of Methven

. Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V

, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas

and the Earl of Moray only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control. Edward I had died in 1307. His heir Edward II

moved an army north to break the siege of Stirling Castle

and reassert control. Robert defeated that army at the Battle of Bannockburn

in 1314, securing de facto independence. In 1320 the Declaration of Arbroath

, a remonstrance to the Pope from the nobles of Scotland, helped convince Pope John XXII

to overturn the earlier excommunication and nullify the various acts of submission by Scottish kings to English ones so that Scotland's sovereignty could be recognised by the major European dynasties. The Declaration has also been seen as one of the most important documents in the development of a Scottish national identity.

and the country was ruled by a series of governors, two of whom died as a result of a renewed invasion by England four years later on the pretext of restoring Edward Balliol

, son of John Balliol, to the Scottish throne, thus starting the Second War of Independence. Despite victories at Dupplin Moor

(1332) and Halidon Hill

(1333), in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray

, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed. Edward III lost interest in the fate of his protege after the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War

with France. In 1341 David was able to return from temporary exile in France. In 1346 under the terms of the Auld Alliance

, he invaded England in the interests of France, but was defeated and taken prisoner at the Battle of Neville's Cross

on 17 October 1346 and would remain in England as a prisoner for eleven years. His cousin Robert Stewart

ruled as guardian in his absence. Balliol finally resigned his claim to the throne to Edward in 1356, before retiring to Yorkshire, where he died in 1364. After eleven years David was released for a ransom of 100,000 marks

in 1357, but he was unable to pay the ransom, resulting in secret negotiations with the English and attempts to secure the Scottish throne for an English king.

After the unexpected death of the childless David II, Robert Stewart, the first of the Stewart (later Stuart) monarchs, came to the throne in 1371. Despite his relatively venerable age of 55, his son, John, Earl of Carrick, grew impatient and assumed the reins of government as Lord Lieutenant. A border incursion into England led to the victory at Otterburn

After the unexpected death of the childless David II, Robert Stewart, the first of the Stewart (later Stuart) monarchs, came to the throne in 1371. Despite his relatively venerable age of 55, his son, John, Earl of Carrick, grew impatient and assumed the reins of government as Lord Lieutenant. A border incursion into England led to the victory at Otterburn

in 1388, but at the cost of the life of John's ally James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas

, helping, along with Carrick having suffered a debilitating horse kick, to a shift in power to his brother Robert Stewart, Earl of Fife, who now was appointed as Lieutenant in his place. When Robert II died in 1390 John took the regnal name

Robert III

, to avoid awkward questions over the exact status of the first King John, but power rested with his brother Robert, now Duke of Albany. After the suspicious death of his elder son, David, Duke of Rothesay in 1402, Robert, fearful for the safety of his younger son, James (the future James I

), sent him to France in 1406. However, the English captured him en route and he spent the next 18 years as a prisoner held for ransom. As a result, after the death of Robert III later that year, regents ruled Scotland: first Albany and after his death in 1420 his son Murdoch, during whose term of office the country suffered considerable unrest. When Scotland finally began the ransom payments in 1424, James, aged 32, returned with his English bride, Joan Beaufort determined to assert this authority. He revoked grants from customs and of lands made during his captivity, undermining the position of those who had gained in his absence, particularly the Albany Stewarts. James had Murdoch and two of his sons, tried and then executed and enforced his authority by arrests and forfeiture of lands. In 1436 he attempted to regain one of the major border fortresses still in English hands at Roxburgh

, but the siege ended in a humiliating defeat. He was murdered by discontented council member Robert Graham and his co-conspirators near the Blackfriars church, Perth

in 1437.

. After the execution of a number of suspected conspirators, leadership fell to Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Douglas

, as lieutenant-general of the realm and after his death in 1439, with general lack of high-status earls because of deaths, forfeiture or youth, power was shared uneasily between William, 1st Lord Crichton

, Lord Chancellor of Scotland, Sir Alexander Livingston of Callendar and James Douglas Earl of Avondale

. In 1440 Edinburgh Castle

became the location for the 'Black Dinner', which saw the summary execution of the young William Douglas, 6th Earl of Douglas

and his brother. Avondale gained the most, becoming the 7th earl of Douglas and eventually he and his family emerged as the major power in the government. In 1449 James II was declared to have reached his majority, but the Douglases consolidated their position and the king began a long struggle for power, leading to the murder of the 8th Earl of Douglas at Stirling Castle on 22 February 1452. This opened an intermittent civil war as James attempted to seize Douglas lands, punctuated by a series of humiliating reversals. Gradually James managed to win over the allies of the Douglases with offers of lands, titles and offices and their forces were finally defeated at the Battle of Arkinholm

on 12 May 1455. Once independent, James II proved to be an active and interventionist king. His attempt to take Roxburgh in 1460 succeeded, but at the cost of his life as he was killed by an exploding artillery piece.

, and his widow Mary of Gueldres acted as regent until her own death 3 years later. The Boyd family, led by Robert, Lord Boyd

emerged as the leading force in the government, making themselves unpopular through self aggrandisement, with Lord Robert's son Thomas

, being made Earl of Arran

and marrying the king's sister, Mary

. While Robert and Thomas were out of the country in 1469 the king asserted his control, executing members of the Boyd family. His foreign policy included a rapprochement with England, with his eldest son, the future James IV

, being betrothed to Cecily of York

, the daughter of Edward IV of England

, a change of policy that was immensely unpopular at home. During the 1470s conflict developed between the king and his brothers, Alexander, Duke of Albany

and John, Earl of Mar

. Mar died suspiciously in 1480 and his estates were forfeited and possibly given to a royal favourite

, Robert Cochrane. Albany fled to France in 1479, accused of treason

. By this point the alliance with England was failing and from 1480 there was intermittent war, followed by a full-scale invasion two years later, led by the Duke of Gloucester, the future Richard III

, and accompanied by Albany. James was imprisoned by his own subjects in Edinburgh Castle

, and Albany was established as lieutenant-general. Having taken Berwick-upon-Tweed

the English retreated and Albany's government began to collapse forcing him to flee. Despite conspiracies and more attempts at invasion, James was able to regain power. However, the king managed to alienate the barons, refusing to travel for the implementation of justice, preferring to be resident in Edinburgh, he debased the coinage, probably creating a financial crisis, he continued to pursue an English alliance and dismissed key supporters, including his Chancellor Colin Campbell, 1st Earl of Argyll

, becoming estranged from his wife, Margaret of Denmark, and his son James. Matters came to a head in 1488 when he faced an army raised by the disaffected nobles, and many former councillors, acting in the name of the prince as James IV. He was defeated at the Battle of Sauchieburn

and killed.

. He defeated a rebellion in 1489, took a direct interest in the administration of justice and finally brought the Lord of the Isles

under control in 1493. For a time he supported Perkin Warbeck

, the pretender to the English throne, and carried out a brief invasion of England on his behalf in 1496. However, he then established good diplomatic relations with England, and in 1502 signed the Treaty of Perpetual Peace, marrying Henry VII's

daughter, Margaret Tudor

, thus laying the foundation for the 17th century Union of the Crowns

. In 1512 the Auld Alliance was renewed and under its terms, when the French were attacked by the English under Henry VIII

, James IV invaded England in support. The invasion was stopped decisively at the battle of Flodden Field

during which the King, many of his nobles, and a large number of ordinary troops were killed, commemorated by the song "The Flooers o' the Forest

". Once again Scotland's government lay in the hands of regents in the name of the infant James V

.

_named_(hr).png) The defining factor in the geography of Scotland is the distinction between the Highlands and Islands

The defining factor in the geography of Scotland is the distinction between the Highlands and Islands

in the north and west and the lowlands

in the south and east. The highlands are further divided into the Northwest Highlands

and the Grampian Mountains by the fault line of the Great Glen

. The lowlands are divided into the fertile belt of the Central Lowlands

and the higher terrain of the Southern Uplands

, which included the Cheviot hills

, over which the border with England came to run by the end of the period. The Central Lowland belt averages about 50 miles in width and, because it contains most of the good quality agricultural land and has easier communications, could support most of the urbanisation and elements of conventional medieval government. However, the Southern Uplands, and particularly the Highlands were economically less productive and much more difficult to govern. This provided Scotland with a form of protection, as minor English incursions had to cross the difficult southern uplands and the two major attempts at conquest by the English, under Edward I and then Edward III, were unable to penetrate the highlands, from which area potential resistance could reconquer the lowlands. However, it also made those areas problematic to govern for Scottish kings and much of the political history of the era after the wars of independence circulated around attempts to resolve problems of entrenched localism in these regions.

It was in the later medieval era that the borders of Scotland reached approximately their modern extent. The Isle of Man

fell under English control in the 14th century, despite several attempts to restore Scottish authority. The English were able to annex a large slice of the lowlands under Edward III, but these losses were gradually regained, particularly while England was preoccupied with the Wars of the Roses

(1455-85). In 1468 the last great acquisition of Scottish territory occurred when James III

married Margaret of Denmark, receiving the Orkney Islands

and the Shetland Islands

in payment of her dowry. However, in 1482 Berwick, a border fortress and the largest port in medieval Scotland, fell to the English once again, for what was to be the final change of hands.

reached the country in 1349. Although we have no reliable documentation on the impact of the plague, there are many anecdotal references to abandoned land in the following decades and if the pattern followed that in England then it may have fallen to as low as half a million by the end of the 15th century. Compared with after the later clearances

and the industrial revolution

, these numbers would have been relatively evenly spread over the kingdom, with roughly half living north of the Tay. Perhaps ten per cent of the population lived in one of fifty burghs that existed at the beginning of the period, mainly in the east and south. It has been suggested that they would have had a mean population of about 2,000, but many would be much smaller than 1,000 and the largest, Edinburgh, probably had a population of over 10,000 by the end of the era.

, settlements of a handful of families that jointly farmed an area notionally suitable for two or three plough teams, allocated in run rig

s to tenant farmers. They usually ran downhill so that they included both wet and dry land, helping to offset some of the problems of extreme weather conditions. Most ploughing was done with a heavy wooden plough with an iron coulter

, pulled by oxen, who were more effective and cheaper to feed than horses. Obligations to the local lord usually included supplying oxen for ploughing the lord's land on an annual basis and the much resented obligation to grind corn at the lord's mill. The rural economy appears to have boomed in the 13th century and in the immediate aftermath of the Black Death was still buoyant, but by the 1360s there was a severe falling off incomes that can be seen in clerical benefices, of between a third and half compared with the beginning of the era, to be followed by a slow recovery in the 15th century.

Most of the burghs were on the east coast, and among them were the largest and wealthiest, including Aberdeen, Perth and Edinburgh, whose growth was facilitated by trade with the continent. Although in the southwest Glasgow

was beginning to develop and Ayr

and Kirkcudbright

had occasional links with Spain and France, sea trade with Ireland was much less profitable. In addition to the major royal burghs this era saw the proliferation of less baronial and ecclesiastical burghs, with 51 being created between 1450 and 1516. Most of these were much smaller than their royal counterparts, excluded from international trade they mainly acted as local markets and centres of craftsmanship. In general burghs probably carried out far more local trading with their hinterlands, relying on them for food, raw materials. The wool trade was a major export at the beginning of the period, but the introduction of sheep-scab

was a serious blow to the trade and it began to decline as an export from the early 15th century and despite a levelling off, there was another drop in exports as the markets collapsed in the early-16th century Low Countries. Unlike in England, this did not prompt the Scots to turn to large scale cloth production and only poor quality rough cloths seem to have been significant.

There were relatively few developed crafts in Scotland in this period, although by the later 15th century there were the beginnings of a native iron casting industry, which led to the production of cannon and of the silver

and goldsmith

ing for which the country would later be known. As a result the most important exports were unprocessed raw materials, including wool, hides, salt, fish, animals and coal, while Scotland remained frequently short of wood, iron and in years of bad harvests grain. Exports of hides and particularly salmon, where the Scots held a decisive advantage in quality over their rivals, appear to have held up much better than wool, despite the general economic downturn in Europe in the aftermath of the plague. The growing desire among the court, lords, upper clergy and wealthier merchants for luxury goods that largely had to be imported led to a chronic shortage of bullion. This, and perennial problems in royal finance, led to several debasements of the coinage, with the amount of silver in a penny being cut to almost a fifth between the late 14th century and the late 15th century. The heavily debased "black money" introduced in 1480 had to be withdrawn two years later and may have helped fuel a financial and political crisis.

, females retained their original surname and marriages were intended to create friendship, rather than kinship. The combination of agnatic kinship and a feudal system of obligation has been seen as creating the highland clan

system, evident in records from the 13th century. Surnames were rare in the highlands until the 17th and 18th centuries and in the middle ages all members of a clan did not share a name and most ordinary members were usually not related to its head. The head of a clan in the beginning of the era was often the strongest male in the main sept

or branch of the clan, but later, as primogeniture

began to dominate, was usually the eldest son of the last chief. The leading families of a clan formed the fine, often seen as equivalent to lowland gentlemen, providing council in peace and leadership in war, and below them were the daoine usisle (in Gaelic) or tacksmen (in Scots), who managed the clan lands and collected the rents. In the isles and along the adjacent western seaboard there were also buannachann, who acted as a military elite, defending the clan lands from raids or taking part in attacks on clan enemies. Most of the followers of the clan were tenants, who supplied labour to the clan heads and sometimes act as soldiers. In the early modern era they would take the clan name as their surname, turning the clan in a massive, if often fictive, kin group.

s (usually descended from very close relatives of the king) and earls, who formed the senior nobility. Below them were the barons, and, from the 1440s, fulfilling the same role were the lords of Parliament, the lowest rank of the nobility able to attend the Estates as of right. There were perhaps 40 to 60 of these in Scotland throughout the period. Below these were the laird

s, roughly equivalent to the English gentlemen. Most were in some sense in the service of the major nobility, either in terms of land or military obligations, roughly half sharing with them their name and a distant and often uncertain form of kinship. Serfdom died out in Scotland in the 14th century, although through the system of courts baron

landlords still exerted considerable control over their tenants. Below the lords and lairds were a variety of groups, often ill-defined. These included yeomen, sometimes called "bonnet lairds", often owning substantial land, and below them the husbandmen, lesser landholders and free tenants that made up the majority of the working population. Society in the burghs was headed by wealthier merchants, who often held local office as a burgess, alderman

, bailies or as a member of the council. A small number of these successful merchants were dubbed knights for their service by the king by the end of the era, although this seems to have been an exceptional form of civic knighthood that did not put them on a par with landed knights. Below them were craftsmen and workers that made up the majority of the urban population.

s from infringing on their trade, monopolies and political power. Craftsmen attempted to emphasise their importance and to break into disputed areas of economic activity, setting prices and standards of workmanship. In the 15th century a series of statutes cemented the political position of the merchants, with limitations on the ability of residents influence the composition of burgh councils and many of the functions of regulation taken on by the bailies. In rural society historians have noted a lack of evidence of widespread unrest similar to that evidenced the Jacquerie

of 1358 in France and the Peasant's Revolt of 1381 in England, possibly because there was relatively little agricultural improvement that could create widespread resentment before the modern era. Instead a major factor was the willingness of tenants to support their betters in any conflict in which they were involved, for which landlords reciprocated with charity and support. Highland and border society acquired a reputation for lawless activity, particularly the feud

. However, more recent interpretations have pointed to the feud as a means of preventing and speedily resolving disputes by forcing arbitration, compensation and resolution.

_i.jpg)

, through formality and elegance putting itself at the centre of culture and political life, defined with display, ritual and pageantry, reflected in elaborate new palaces and patronage of the arts.

, composed of the king's closest advisers, but which, unlike in England, retained legislative and judicial powers. It was relatively small, with normally less than 10 members in a meeting, some of whom were nominated by Parliament, particularly during the many minorities of the era, as a means of limiting the power of a regent. The council was a virtually full-time institution by the late 15th century, and surviving records from the period indicate it was critical in the working of royal justice. Nominally members of the council were some of the great magnates of the realm, but they rarely attended meetings. Most of the active members of the council for most of the period were career administrators and lawyers, almost exclusively university-educated clergy, the most successful of which moved on to occupy the major ecclesiastical positions in the realm as bishops and, towards the end of the period, archbishops. By the end of the 15th century this group was being joined by increasing numbers of literate laymen, often secular lawyers, of which the most successful gained preferment in the judicial system and with grants of lands and lordships. From the reign of James III onwards the clerically dominated post of Lord Chancellor

was increasingly taken by leading laymen.

The next most important body in the process of government was parliament

The next most important body in the process of government was parliament

, which had evolved by the late 13th century from the King's Council of Bishops and Earls into a ‘colloquium’ with a political and judicial role. By the early 14th century, the attendance of knight

s and freeholders

had become important, and probably from 1326 burgh

commissioners joined them to form the Three Estates, meeting in a variety of major towns throughout the kingdom. It acquired significant powers over particular issues, including consent for taxation, but it also had a strong influence over justice, foreign policy, war, and other legislation, whether political, ecclesiastical, social or economic. From the early 1450s, a great deal of the legislative business of the Scottish Parliament was usually carried out by a parliamentary committee known as the ‘Lords of the Articles’, chosen by the three estates to draft legislation which was then presented to the full assembly to be confirmed. Parliamentary business was also carried out by ‘sister’ institutions, before c. 1500 by General Council

and thereafter by the Convention of Estates

. These could carry out much business also dealt with by Parliament—taxation, legislation and policy-making—but lacked the ultimate authority of a full parliament. In the 15th century parliament was being called on an almost annual basis, more often than its English counterpart, and was willing to offer occasional resistance or criticism to the policies of the crown, particular in the unpopular reign of James III. However, from about 1494, after his success against the Stewarts and Douglases and over rebels in 1482 and 1488, James IV managed to largely dispense with the institution and it might have declined, like many other systems of Estates in continental Europe, had it not been for his death in 1513 and another long minority.

and Crawford

, thanks to royal patronage after the Wars of Independence, mainly in the borders and south-west. The dominant kindred were the Stewarts, who came to control many of the earldoms. Their acquisition of the crown, and a series of internal conflicts and confiscations, meant that by around 1460s the monarchy had transformed its position within the realm, gaining control of most of the "provincial" earldoms and lordships. Rather than running semi-independent lordships, the major magnates now had scattered estates and occasional regions of major influence. In the lowlands the crown was now able to administer government through a system of sheriffdoms and other appointed officers, rather than semi-independent lordships. In the highlands James II created two new provincial earldoms for his favourites: Argyll for the Campbells

and Huntly for the Gordons

, which acted as a bulwark against the vast Lordship of the Isles

built up by the Macdonalds

. James IV largely resolved the Macdonald problem by annexing the estates and titles of John Macdonald II to the crown in 1493 after discovering his plans for an alliance with the English.

Scottish armies of the late medieval era depended on a combination of familial, communal and feudal forms of service. "Scottish service" (servitum Scoticanum), also known as "common service" (communis exertcitus), a levy of all able-bodied freemen aged between 16 and 60, provided the bulk of armed forces, with (according to decrees) 8-days warning. Feudal obligations, by which knights held castles and estates in exchange for service, provided troops on a 40 day basis. By the second half of the 14th century money contracts of bonds or bands of manrent

Scottish armies of the late medieval era depended on a combination of familial, communal and feudal forms of service. "Scottish service" (servitum Scoticanum), also known as "common service" (communis exertcitus), a levy of all able-bodied freemen aged between 16 and 60, provided the bulk of armed forces, with (according to decrees) 8-days warning. Feudal obligations, by which knights held castles and estates in exchange for service, provided troops on a 40 day basis. By the second half of the 14th century money contracts of bonds or bands of manrent

, similar to English indentures of the same period, were being used to retain more professional troops, particular men-at-arms and archers

. In practice forms of service tended to blur and overlap and several major Scottish lords brought contingents from their kindred.

These systems produced relatively large numbers of poorly armoured infantry, often armed with 12-14 foot spears. They often formed the large close order defensive formations of shiltrons, able to counter mounted knights as they did at Bannockburn, but vulnerable to arrows (and later artillery

fire) and relatively immobile, as they proved at Halidon Hill. There were attempts to replace spears with longer pikes of 15½ to 18½ feet in the later 15th century, in emulation of successes over mounted troops in the Netherlands and Switzerland, but this does not appear to have been successful until the eve of the Flodden campaign in early 16th century. There were smaller numbers of archers and men-at-arms, which were often outnumbered when facing the English on the battlefield. Archers became much sought after as mercenaries in French armies of the 15th century in order to help counter the English superiority in this arm, becoming a major element of the French royal guards. Scottish men-at-arms often dismounted to fight beside the infantry, with perhaps a small mounted reserve, and it has been suggested that these tactics were copied and refined by the English, leading to their successes in the Hundred Years War.

The Stewarts attempted to follow France and England in building up an artillery train. James II had a royal gunner and his enthusiasm for artillery cost him his life. James IV brought in experts from France, Germany and the Netherlands and established a foundry in 1511. Edinburgh Castle had a house of artillery where visitors could see cannon cast for what became a formidable train, allowing him to send cannon to France and Ireland and to quickly subdue Norham Castle

in the Flodden campaign.

Various attempts had been made to build up a royal naval force, but James IV put the enterprise on a new footing, founding two new dockyards and acquired a total of 38 ships for the Royal Scottish Navy, including the Margaret

, and the carrack

Michael

or Great Michael. The latter, built at great expense at Newhaven

and launched in 1511, was 240 feet (73 m) in length, weighed 1,000 tons, had 24 cannon, and was, at that time, the largest ship in Europe.

Since gaining its independence from English ecclesiastical organisation in 1192, the Catholic Church in Scotland had been a "special daughter of the see of Rome", enjoying a direct relationship with the Papacy. Lacking archbishoprics, it was in practice run by special councils of made up of all the bishops, with the bishop of St Andrews emerging as the most important player, until in 1472 St Andrews became the first archbishopric, to be followed by Glasgow in 1492. Late medieval religion had its political aspects, with Robert I carrying the brecbennoch (or Monymusk reliquary

Since gaining its independence from English ecclesiastical organisation in 1192, the Catholic Church in Scotland had been a "special daughter of the see of Rome", enjoying a direct relationship with the Papacy. Lacking archbishoprics, it was in practice run by special councils of made up of all the bishops, with the bishop of St Andrews emerging as the most important player, until in 1472 St Andrews became the first archbishopric, to be followed by Glasgow in 1492. Late medieval religion had its political aspects, with Robert I carrying the brecbennoch (or Monymusk reliquary

), said to contain the remains of St. Columba, into battle at Bannockburn and James IV using his pilgrimages to Tain

and Whithorn

to help bring Ross and Galloway under royal authority. There were also further attempts to differentiate Scottish liturgical practice from that in England, with a printing press established under royal patent in 1507 in order to replace the English Sarum Use for services. As elsewhere in Europe, the collapse of papal authority in the Papal Schism had allowed the Scottish crown to gain effective control of major ecclesiastical appointments within the kingdom, a position recognised by the Papacy in 1487. This led to the placement of clients and relatives of the king in key positions, including James IV's illegitimate son Alexander

, who was nominated as Archbishop of St. Andrews at the age of eleven, intensifying royal influence and also opening the Church to accusations of venality and nepotism

. Despite this, relationships between the Scottish crown and the Papacy were generally good, with James IV receiving tokens of papal favour.

Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated the ways in which it met the spiritual needs of different social groups. Historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in this period, with many religious houses keeping smaller numbers of monks, and those remaining often abandoning communal living for a more individual and secular lifestyle. New monastic endowments from the nobility also declined in the 15th century. In contrast, the burghs saw the flourishing of mendicant

orders of friar

s in the later 15th century, who placed an emphasis on preaching and ministering to the population. The order of Observant Friar

s were organised as a Scottish province from 1467 and the older Franciscans and Dominicans

were recognised as separate provinces in the 1480s. In most burghs, in contrast to English towns where churches tended to proliferate, there was usually only one parish church, but as the doctrine of Purgatory

gained in importance in the period, the number of chapelries, priests and masses for the dead within them grew rapidly. The number of altars to saints also grew dramatically, with St. Mary's in Dundee

having perhaps 48 and St Giles' in Edinburgh over 50, as did the number of saints celebrated in Scotland, with about 90 being added to the missal

used in St Nicholas church in Aberdeen

. New cults of devotion connected with Jesus and the Virgin Mary also began to reach Scotland in the 15th century, including The Five Wounds, The Holy Blood

and The Holy Name of Jesus

and new feasts including The Presentation, The Visitation and Mary of the Snows

. In the early 14th century the Papacy managed to minimise the problem of clerical pluralism, but with relatively poor livings and a shortage of clergy, particularly after the Black Death, in the 15th century the number of clerics holding two or more livings rapidly increased. This meant that parish clergy were largely drawn from the lower and less educated ranks of the profession, leading to frequent complaints about their standards of education or ability, although there is little clear evidence that this was actually declining. Heresy, in the form of Lollardry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early 15th century, but despite evidence of a number of burnings and some apparent support for its anti-sacramental elements, it probably remained a relatively small movement.

in 1413, the University of Glasgow

in 1450 and the University of Aberdeen

in 1495, and with the passing of the Education Act 1496

, which decreed that all sons of barons and freeholders of substance should attend grammar schools. All this resulted in an increase in literacy, but which was largely concentrated among a male and wealthy elite.

, was characterised by corbel

led turrets and crow-stepped gable

s marked the first uniquely Scottish mode of building. Ceilings

of these houses were decorated with vividly coloured painting on boards and beams, using emblem

atic motifs from European pattern books or the artist's interpretation of trailing grotesque patterns. The grandest buildings of this type were the royal palaces in this style at Linlithgow

, Holyrood

, Falkland

and the remodelled Stirling Castle

, all of which have elements of continental European architecture, particularly from France and the Low Countries, adapted to Scottish idioms and materials (particularly stone and harl

). More modest buildings with continental influences can be seen in the late 15th century western tower of St Mary's parish church, Dundee; and tollbooths like the one at Dunbar.

Parish church architecture in Scotland was often much less elaborate than in England, with many churches remaining simple oblongs, without transept

s and aisle

s, and often without towers. In the highlands they were often even simpler, many built of rubble masonry and sometimes indistinguishable from the outside from houses or farm buildings. However, there were some churches built in a grander continental style. French master-mason John Morrow was employed at the building of Glasgow Cathedral

and the rebuilding of Melrose Abbey

, both considered fine examples of Gothic architecture. The interiors of churches were often more elaborate before the Reformation, with highly decorated sacrament houses, like the ones surviving at Deskford and Kinkell. The carvings at Rosslyn Chapel

, created in the mid-15th century, elaborately depicting the progression of the seven deadly sins

, are considered some of the finest in the Gothic style. Late medieval Scottish churches also often contained elaborate burial monuments, like the Douglas tombs in the town of Douglas

.

We have relatively little information about native Scottish artists in this period. As in England, the monarchy may have had model portraits used for copies and reproductions, but the versions that survive are generally crude by continental standards. Much more impressive are the works or artists imported from the continent, particularly the Netherlands, generally considered the centre of painting in the Northern Renaissance

. The products of these connections included the delicate hanging lamp in St. John's Kirk in Perth

; the tabernacles and images of St Catherine and St John brought to Dunkeld

, and vestments and hangings in Holyrood; Hugo van Der Goes

's altarpiece for the Trinity College Church in Edinburgh

, commissioned by James III, the work after which the Flemish Master of James IV of Scotland

is named, and the illustrated Flemish Bening

Book of Hours

, given by James IV to Margaret Tudor.

, often called "English" in this period, was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French

. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late 14th century onwards. It was the dominant language of the lowlands and borders, brought there largely by Anglo-Saxon settlers from the 5th century, but began to be adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French in the late medieval era. By the 15th century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result Gaelic, once dominant north of the Tay, began a steady decline.

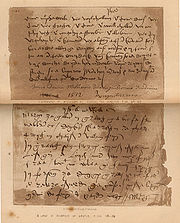

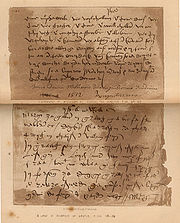

Gaelic was the language of the bardic tradition, which provided a mechanism for the transference of oral culture from generation to generation. Members of bardic schools were trained in the complex rules and forms of Gaelic poetry. In a non-literate society they were the repositories of knowledge, including not just stories and songs, but also genealogies and medicine and were found in many of the courts of the great lords, down to the chiefdoms of the highlands at the beginning of the period. The bardic tradition was not completely isolated from trends elsewhere, including love poetry influenced by continental developments and with medical manuscripts from Padua, Salerno and Montpellier translated from Latin. The Gaelic oral tradition also began to manifest itself in written form, with the great compilation of Gaelic poetry, the Book of the Dean of Lismore

Gaelic was the language of the bardic tradition, which provided a mechanism for the transference of oral culture from generation to generation. Members of bardic schools were trained in the complex rules and forms of Gaelic poetry. In a non-literate society they were the repositories of knowledge, including not just stories and songs, but also genealogies and medicine and were found in many of the courts of the great lords, down to the chiefdoms of the highlands at the beginning of the period. The bardic tradition was not completely isolated from trends elsewhere, including love poetry influenced by continental developments and with medical manuscripts from Padua, Salerno and Montpellier translated from Latin. The Gaelic oral tradition also began to manifest itself in written form, with the great compilation of Gaelic poetry, the Book of the Dean of Lismore

produced by James and Duncan MacGregor at the beginning of the 16th century, probably designed for use in the courts of the greater chiefs. However, by the 15th century lowland writers were beginning to treat Gaelic as a second class, rustic and even amusing language, helping to frame attitudes towards the highlands and to create a cultural gulf with the lowlands.

It was Scots that emerged as the language of national literature in Scotland. The first surviving major text is John Barbour's Brus

(1375), composed under the patronage of Robert II and telling the story in epic poetry of Robert I's actions before the English invasion till the end of the war of independence. The work was extremely popular among the Scots-speaking aristocracy and Barbour is referred to as the father of Scots poetry, holding a similar place to his contemporary Chaucer in England. In the early 15th century these were followed by Andrew of Wyntoun

's verse Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland and Blind Harry

's The Wallace

, which blended historical romance

with the verse chronicle

. They were probably influenced by Scots versions of popular French romances that were also produced in the period, including The Buik of Alexander

, Launcelot o the Laik

and The Porteous of Noblenes by Gibert Hay.

Much Middle Scots literature was produced by makars, poets with links to the royal court. At least two of Scotland's kings in the period were themselves makars, James I

(who wrote The Kingis Quair

) and his descendant James VI. Many of the makars had university education and so were also connected with the Kirk. However, Dunbar's Lament for the Makaris

(c.1505) provides evidence of a wider tradition of secular writing outside of Court and Kirk now largely lost. Before the advent of printing in Scotland, writers such as Robert Henryson

, William Dunbar

, Walter Kennedy

and Gavin Douglas

have been seen as leading a golden age in Scottish poetry.

In the late 15th century, Scots prose also began to develop as a genre. Although there are earlier fragments of original Scots prose, such as the Auchinleck Chronicle, the first complete surviving work includes John Ireland's The Meroure of Wyssdome (1490). There were also prose translations of French books of chivalry that survive from the 1450s, including The Book of the Law of Armys and the Order of Knychthode and the treatise Secreta Secetorum

, an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice to Alexander the Great. The landmark work in the reign of James IV

was Gavin Douglas

's version of Virgil

's Aeneid

, the Eneados

, which was the first complete translation of a major classical text in an Anglian language, finished in 1513, but overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden.

Bards, who acted as musicians, but also as poets, story tellers, historians, genealogists and lawyers, relying on an oral tradition that stretched back generations, were found in Scotland as well as Wales and Ireland. Often accompanying themselves on the harp

Bards, who acted as musicians, but also as poets, story tellers, historians, genealogists and lawyers, relying on an oral tradition that stretched back generations, were found in Scotland as well as Wales and Ireland. Often accompanying themselves on the harp

, they can also be seen in records of the Scottish courts throughout the medieval period. Scottish church music from the later middle ages was increasingly influenced by continental developments, with figures like 13th-century musical theorist Simon Tailler studying in Paris, before returned to Scotland where he introduced several reforms of church music. Scottish collections of music like the 13th-century 'Wolfenbüttel 677', which is associated with St Andrews

, contain mostly French compositions, but with some distinctive local styles. The captivity of James I in England from 1406 to 1423, where he earned a reputation as a poet and composer, may have led him to take English and continental styles and musicians back to the Scottish court on his release. In the late 15th century a series of Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands before returning home, including John Broune, Thomas Inglis and John Fety, the last of whom became master of the song school in Aberdeen and then Edinburgh, introducing the new five-fingered organ playing technique. In 1501 James IV refounded the Chapel Royal within Stirling Castle

, with a new and enlarged choir and it became the focus of Scottish liturgical music. Burgundian and English influences were probably reinforced when Henry VII's daughter Margaret Tudor married James IV in 1503.

The adoption of Middle Scots by the aristocracy has been seen as building a sense of national solidarity and culture between rulers and ruled, although the fact that North of the Tay Gaelic still dominated, may have helped widen the cultural divide between highlands and lowlands. The national literature of Scotland created in the late medieval period employed legend and history in the service of the crown and nationalism, helping to foster a sense of national identity at least within its elite audience. The epic poetic history of the Brus and Wallace helped outline a narrative of united struggle against the English enemy. Arthurian literature differed from conventional version of the legend by treating Arthur

The adoption of Middle Scots by the aristocracy has been seen as building a sense of national solidarity and culture between rulers and ruled, although the fact that North of the Tay Gaelic still dominated, may have helped widen the cultural divide between highlands and lowlands. The national literature of Scotland created in the late medieval period employed legend and history in the service of the crown and nationalism, helping to foster a sense of national identity at least within its elite audience. The epic poetic history of the Brus and Wallace helped outline a narrative of united struggle against the English enemy. Arthurian literature differed from conventional version of the legend by treating Arthur

as a villain and Mordred

, the son of the king of the Picts, as a hero. The origin myth of the Scots, systematised by John of Fordun

(c. 1320-c. 1384), traced their beginnings from the Greek prince Gathelus and his Egyptian wife Scota

, allowing them to argue superiority over the English, who claimed their descent from the Trojans, who had been defeated by the Greeks.

It was in this period that the national flag emerged as a common symbol. The image of St. Andrew, martyred while bound to an X-shaped cross, first appeared in the Kingdom of Scotland

during the reign of William I

and was again depicted on seals used during the late 13th century; including on one particular example used by the Guardians of Scotland, dated 1286. Use of a simplified symbol associated with Saint Andrew, the saltire

, has its origins in the late 14th century; the Parliament of Scotland

decreed in 1385 that Scottish soldiers wear a white Saint Andrew's Cross on their person, both in front and behind, for the purpose of identification. Use of a blue background for the Saint Andrew's Cross is said to date from at least the 15th century. The earliest reference to the Saint Andrew's Cross as a flag is to be found in the Vienna Book of Hours, circa 1503.

William Wallace

Sir William Wallace was a Scottish knight and landowner who became one of the main leaders during the Wars of Scottish Independence....

in the late 13th century and Robert Bruce

Robert I of Scotland

Robert I , popularly known as Robert the Bruce , was King of Scots from March 25, 1306, until his death in 1329.His paternal ancestors were of Scoto-Norman heritage , and...

in the 14th century. In the 15th century under the Stewart Dynasty, despite a turbulent political history, the crown gained greater political control at the expense of independent lords and restored most of its lost territory to approximately the modern borders of the country. However, the Auld Alliance

Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance was an alliance between the kingdoms of Scotland and France. It played a significant role in the relations between Scotland, France and England from its beginning in 1295 until the 1560 Treaty of Edinburgh. The alliance was renewed by all the French and Scottish monarchs of that...

with France led to the heavy defeat of a Scottish army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513 and the death of the king James IV

James IV of Scotland

James IV was King of Scots from 11 June 1488 to his death. He is generally regarded as the most successful of the Stewart monarchs of Scotland, but his reign ended with the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Flodden Field, where he became the last monarch from not only Scotland, but also from all...

, which would be followed by a long minority and a period of political instability.

The economy of Scotland developed slowly in this period and population of perhaps a million by the middle of the 14th century began to decline after the arrival of the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

, falling to perhaps half a million by the beginning of the 16th century. Different social systems and cultures developed in the lowland and highland regions of the country as Gaelic remained the most common language north of the Tay

Tay

-People:* Warren Tay, British ophthalmologist** Tay-Sachs disease, named after Warren Tay* Tay, nickname of the basketball player Tayshaun Prince* Tay Zonday, singer* Tay people, an ethnic group in Vietnam* Arturo Tay Mexican Filmmaker-Places:...

and Middle Scots

Middle Scots

Middle Scots was the Anglic language of Lowland Scotland in the period from 1450 to 1700. By the end of the 13th century its phonology, orthography, accidence, syntax and vocabulary had diverged markedly from Early Scots, which was virtually indistinguishable from early Northumbrian Middle English...

dominated in the south, where it became the language of the ruling elite, government and a new national literature. There were significant changes in religion which saw mendicant

Mendicant

The term mendicant refers to begging or relying on charitable donations, and is most widely used for religious followers or ascetics who rely exclusively on charity to survive....

friars and new devotions expand, particularly in the developing burgh

Burgh

A burgh was an autonomous corporate entity in Scotland and Northern England, usually a town. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Burgh status was broadly analogous to borough status, found in the rest of the United...

s.

By the end of the period Scotland had adopted many of the major tenants of the European Renaissance in art, architecture and literature and produced a developed educational system. This period has been seen as seeing a clear national identity emerge in Scotland as well as significant distinctions between different regions of the country which would be particularly significant in the period of the Reformation.

Political history

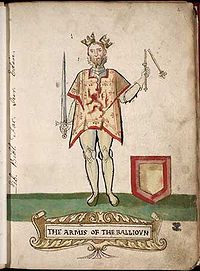

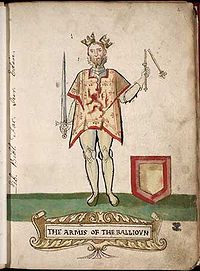

John I

The death of king Alexander IIIAlexander III of Scotland

Alexander III was King of Scots from 1249 to his death.-Life:...

in 1286, and the subsequent death of his granddaughter and heir Margaret

Margaret, Maid of Norway

Margaret , usually known as the Maid of Norway , sometimes known as Margaret of Scotland , was a Norwegian princess who was Queen of Scots from 1286 until her death...

(called "the Maid of Norway") in 1290, left 14 rivals for succession. To prevent civil war the Scottish magnates asked Edward I of England

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

to arbitrate, for which he extracted legal recognition that the realm of Scotland was held as a feudal dependency to the throne of England before choosing John Balliol, the man with the strongest claim, who became king as John I (30 November 1292). Robert Bruce of Annandale, the next strongest claimant, accepted this outcome with reluctance. Over the next few years Edward I used the concessions he had gained to systematically undermine both the authority of King John and the independence of Scotland. In 1295 John, on the urgings of his chief councillors, entered into an alliance with France, the beginning of the Auld Alliance

Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance was an alliance between the kingdoms of Scotland and France. It played a significant role in the relations between Scotland, France and England from its beginning in 1295 until the 1560 Treaty of Edinburgh. The alliance was renewed by all the French and Scottish monarchs of that...

.

In 1296 Edward invaded Scotland, deposing King John. The following year William Wallace

William Wallace

Sir William Wallace was a Scottish knight and landowner who became one of the main leaders during the Wars of Scottish Independence....

and Andrew de Moray raised forces to resist the occupation and under their joint leadership an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge

Battle of Stirling Bridge

The Battle of Stirling Bridge was a battle of the First War of Scottish Independence. On 11 September 1297, the forces of Andrew Moray and William Wallace defeated the combined English forces of John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey and Hugh de Cressingham near Stirling, on the River Forth.-The main...

. For a short time Wallace ruled Scotland in the name of John Balliol as Guardian

Guardian of Scotland

The Guardians of Scotland were the de facto heads of state of Scotland during the First Interregnum of 1290–1292, and the Second Interregnum of 1296–1306...

of the realm. Edward came north in person and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk (1298)

Battle of Falkirk (1298)

The Battle of Falkirk, which took place on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence...

. Wallace escaped but probably resigned as Guardian of Scotland. In 1305 he fell into the hands of the English, who executed him for treason despite the fact that he owed no allegiance to England.

Robert I

John III Comyn, Lord of Badenoch

John III Comyn, Lord of Badenoch and Lord of Lochaber or John "the Red", also known simply as the Red Comyn was a Scottish nobleman who was an important figure in the Wars of Scottish Independence, and was Guardian of Scotland during the Second Interregnum 1296-1306...

and Robert the Bruce

Robert I of Scotland

Robert I , popularly known as Robert the Bruce , was King of Scots from March 25, 1306, until his death in 1329.His paternal ancestors were of Scoto-Norman heritage , and...

, grandson of the claimant, were appointed as joint guardians in his place. On 10 February 1306, Bruce participated in the murder of Comyn, at Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries

Dumfries

Dumfries is a market town and former royal burgh within the Dumfries and Galloway council area of Scotland. It is near the mouth of the River Nith into the Solway Firth. Dumfries was the county town of the former county of Dumfriesshire. Dumfries is nicknamed Queen of the South...

. Less than seven weeks later, on March 25, Bruce was crowned as King. However, Edward's forces overran the country after defeating Bruce's small army at the Battle of Methven

Battle of Methven

The Battle of Methven took place at Methven in Scotland in 1306, during the Wars of Scottish Independence.-Comyn's Death:In February 1306, Robert Bruce and a small party of his followers killed John Comyn, also known as the Red Comyn, before the high altar of the Greyfriars Church in Dumfries...

. Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V

Pope Clement V, born Raymond Bertrand de Got was Pope from 1305 to his death...

, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas

James Douglas, Lord of Douglas

Sir James Douglas , , was a Scottish soldier and knight who fought in the Scottish Wars of Independence.-Early life:...

and the Earl of Moray only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control. Edward I had died in 1307. His heir Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

moved an army north to break the siege of Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most important castles, both historically and architecturally, in Scotland. The castle sits atop Castle Hill, an intrusive crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill geological formation. It is surrounded on three sides by steep...

and reassert control. Robert defeated that army at the Battle of Bannockburn

Battle of Bannockburn

The Battle of Bannockburn was a significant Scottish victory in the Wars of Scottish Independence...

in 1314, securing de facto independence. In 1320 the Declaration of Arbroath

Declaration of Arbroath

The Declaration of Arbroath is a declaration of Scottish independence, made in 1320. It is in the form of a letter submitted to Pope John XXII, dated 6 April 1320, intended to confirm Scotland's status as an independent, sovereign state and defending Scotland's right to use military action when...

, a remonstrance to the Pope from the nobles of Scotland, helped convince Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII , born Jacques Duèze , was pope from 1316 to 1334. He was the second Pope of the Avignon Papacy , elected by a conclave in Lyon assembled by Philip V of France...

to overturn the earlier excommunication and nullify the various acts of submission by Scottish kings to English ones so that Scotland's sovereignty could be recognised by the major European dynasties. The Declaration has also been seen as one of the most important documents in the development of a Scottish national identity.

David II

Robert I died in 1329, leaving his 5-year-old son to reign as David IIDavid II of Scotland

David II was King of Scots from 7 June 1329 until his death.-Early life:...

and the country was ruled by a series of governors, two of whom died as a result of a renewed invasion by England four years later on the pretext of restoring Edward Balliol

Edward Balliol

Edward Balliol was a claimant to the Scottish throne . With English help, he briefly ruled the country from 1332 to 1336.-Life:...

, son of John Balliol, to the Scottish throne, thus starting the Second War of Independence. Despite victories at Dupplin Moor

Battle of Dupplin Moor

The Battle of Dupplin Moor was fought between supporters of the infant David II, the son of Robert the Bruce, and rebels supporting the Balliol claim in 1332. It was a significant battle of the Second War of Scottish Independence.-Background:...

(1332) and Halidon Hill

Battle of Halidon Hill

The Battle of Halidon Hill was fought during the Second War of Scottish Independence. Scottish forces under Sir Archibald Douglas were heavily defeated on unfavourable terrain while trying to relieve Berwick-upon-Tweed.-The Disinherited:...

(1333), in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray

Sir Andrew Murray

Sir Andrew Murray , also known as Sir Andrew Moray or Sir Andrew Murray of Bothwell, was a Scottish military leader who commanded resistance forces loyal to David II of Scotland against Edward Balliol and Edward III of England during the Second War of Scottish Independence...

, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed. Edward III lost interest in the fate of his protege after the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a series of separate wars waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, also known as the House of Anjou, for the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior Capetian line of French kings...

with France. In 1341 David was able to return from temporary exile in France. In 1346 under the terms of the Auld Alliance

Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance was an alliance between the kingdoms of Scotland and France. It played a significant role in the relations between Scotland, France and England from its beginning in 1295 until the 1560 Treaty of Edinburgh. The alliance was renewed by all the French and Scottish monarchs of that...

, he invaded England in the interests of France, but was defeated and taken prisoner at the Battle of Neville's Cross

Battle of Neville's Cross

The Battle of Neville's Cross took place to the west of Durham, England on 17 October 1346.-Background:In 1346, England was embroiled in the Hundred Years' War with France. In order to divert his enemy Philip VI of France appealed to David II of Scotland to attack the English from the north in...

on 17 October 1346 and would remain in England as a prisoner for eleven years. His cousin Robert Stewart

Robert II of Scotland

Robert II became King of Scots in 1371 as the first monarch of the House of Stewart. He was the son of Walter Stewart, hereditary High Steward of Scotland and of Marjorie Bruce, daughter of Robert I and of his first wife Isabella of Mar...

ruled as guardian in his absence. Balliol finally resigned his claim to the throne to Edward in 1356, before retiring to Yorkshire, where he died in 1364. After eleven years David was released for a ransom of 100,000 marks

Mark (money)

Mark was a measure of weight mainly for gold and silver, commonly used throughout western Europe and often equivalent to 8 ounces. Considerable variations, however, occurred throughout the Middle Ages Mark (from a merging of three Teutonic/Germanic languages words, Latinized in 9th century...

in 1357, but he was unable to pay the ransom, resulting in secret negotiations with the English and attempts to secure the Scottish throne for an English king.

Robert II, Robert III and James I

Battle of Otterburn

The Battle of Otterburn took place on the 5 August 1388, as part of the continuing border skirmishes between the Scottish and English.The best remaining record of the battle is from Jean Froissart's Chronicles in which he claims to have interviewed veterans from both sides of the battle...

in 1388, but at the cost of the life of John's ally James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas

James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas

Sir James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas and Mar was an influential and powerful magnate in the Kingdom of Scotland.-Early life:He was the eldest son and heir of William Douglas, 1st Earl of Douglas and Margaret, Countess of Mar...

, helping, along with Carrick having suffered a debilitating horse kick, to a shift in power to his brother Robert Stewart, Earl of Fife, who now was appointed as Lieutenant in his place. When Robert II died in 1390 John took the regnal name

Regnal name

A regnal name, or reign name, is a formal name used by some monarchs and popes during their reigns. Since medieval times, monarchs have frequently chosen to use a name different from their own personal name when they inherit a throne....

Robert III

Robert III of Scotland

Robert III was King of Scots from 1390 to his death. His given name was John Stewart, and he was known primarily as the Earl of Carrick before ascending the throne at age 53...

, to avoid awkward questions over the exact status of the first King John, but power rested with his brother Robert, now Duke of Albany. After the suspicious death of his elder son, David, Duke of Rothesay in 1402, Robert, fearful for the safety of his younger son, James (the future James I

James I of Scotland

James I, King of Scots , was the son of Robert III and Annabella Drummond. He was probably born in late July 1394 in Dunfermline as youngest of three sons...

), sent him to France in 1406. However, the English captured him en route and he spent the next 18 years as a prisoner held for ransom. As a result, after the death of Robert III later that year, regents ruled Scotland: first Albany and after his death in 1420 his son Murdoch, during whose term of office the country suffered considerable unrest. When Scotland finally began the ransom payments in 1424, James, aged 32, returned with his English bride, Joan Beaufort determined to assert this authority. He revoked grants from customs and of lands made during his captivity, undermining the position of those who had gained in his absence, particularly the Albany Stewarts. James had Murdoch and two of his sons, tried and then executed and enforced his authority by arrests and forfeiture of lands. In 1436 he attempted to regain one of the major border fortresses still in English hands at Roxburgh

Roxburgh

Roxburgh , also known as Rosbroch, is a village, civil parish and now-destroyed royal burgh. It was an important trading burgh in High Medieval to early modern Scotland...

, but the siege ended in a humiliating defeat. He was murdered by discontented council member Robert Graham and his co-conspirators near the Blackfriars church, Perth

Blackfriars, Perth

The Church of the Friars Preachers of Blessed Virgin and Saint Dominic at Perth, commonly called "Blackfriars", was a mendicant friary of the Dominican Order founded in the 13th century at Perth, Scotland...

in 1437.

James II

The assassination left the king's 7-year-old son to reign as James IIJames II of Scotland

James II reigned as King of Scots from 1437 to his death.He was the son of James I, King of Scots, and Joan Beaufort...

. After the execution of a number of suspected conspirators, leadership fell to Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Douglas

Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Douglas

Archibald Douglas was a Scottish nobleman and General, son of Archibald Douglas, 4th Earl of Douglas and Margaret Stewart, eldest daughter of Robert III...

, as lieutenant-general of the realm and after his death in 1439, with general lack of high-status earls because of deaths, forfeiture or youth, power was shared uneasily between William, 1st Lord Crichton

William Crichton, 1st Lord Crichton

William Crichton, 1st Lord Crichton of Sanquhar was an important political figure in Scotland.He held various positions within the court of James I. At the death of James I, William Crichton was Sheriff of Edinburgh, Keeper of Edinburgh Castle, and Master of the King’s household...

, Lord Chancellor of Scotland, Sir Alexander Livingston of Callendar and James Douglas Earl of Avondale

James Douglas, 7th Earl of Douglas

James Douglas, 7th Earl of Douglas, 1st Earl of Avondale , known as "the Gross", was a Scottish nobleman. He was the second son of Archibald Douglas, 3rd Earl of Douglas and Joan Moray of Bothwell and Drumsargard , d...

. In 1440 Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a fortress which dominates the skyline of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, from its position atop the volcanic Castle Rock. Human habitation of the site is dated back as far as the 9th century BC, although the nature of early settlement is unclear...

became the location for the 'Black Dinner', which saw the summary execution of the young William Douglas, 6th Earl of Douglas

William Douglas, 6th Earl of Douglas

William Douglas was a short-lived Scottish Nobleman. He was Earl of Douglas and Wigtown, Lord of Galloway, Lord of Bothwell, Selkirk and Ettrick Forest, Eskdale, Lauderdale, and Annandale in Scotland, and de jure Duke of Touraine, Count of Longueville, and Sire of Dun-le-roi in France...

and his brother. Avondale gained the most, becoming the 7th earl of Douglas and eventually he and his family emerged as the major power in the government. In 1449 James II was declared to have reached his majority, but the Douglases consolidated their position and the king began a long struggle for power, leading to the murder of the 8th Earl of Douglas at Stirling Castle on 22 February 1452. This opened an intermittent civil war as James attempted to seize Douglas lands, punctuated by a series of humiliating reversals. Gradually James managed to win over the allies of the Douglases with offers of lands, titles and offices and their forces were finally defeated at the Battle of Arkinholm

Battle of Arkinholm

The Battle of Arkinholm was fought on May 1, 1455, at Arkinholm near Langholm in Scotland, during the reign of King James II of Scotland.Although a small action, involving only a few hundred troops, it was the decisive battle in a civil war between the king and the Black Douglases, the most...

on 12 May 1455. Once independent, James II proved to be an active and interventionist king. His attempt to take Roxburgh in 1460 succeeded, but at the cost of his life as he was killed by an exploding artillery piece.

James III

James II's son, aged 9 or 10, became king as James IIIJames III of Scotland

James III was King of Scots from 1460 to 1488. James was an unpopular and ineffective monarch owing to an unwillingness to administer justice fairly, a policy of pursuing alliance with the Kingdom of England, and a disastrous relationship with nearly all his extended family.His reputation as the...

, and his widow Mary of Gueldres acted as regent until her own death 3 years later. The Boyd family, led by Robert, Lord Boyd

Robert Boyd, 1st Lord Boyd

Robert Boyd, 1st Lord Boyd Lord Boyd, was a Scottish statesman.-Biography:Robert Boyd was knighted, and was created a Peer of Parliament by James II of Scotland at some date between 1451 and 18 July 1454 . In 1460 he was one of the Regents during the minority of James III...

emerged as the leading force in the government, making themselves unpopular through self aggrandisement, with Lord Robert's son Thomas

Thomas Boyd, 1st Earl of Arran

Thomas Boyd, Earl of Arran was a Scottish nobleman.Thomas was the son of Robert, 1st Lord Boyd, who was a regent during the minority of James III. His father was able have Thomas created Earl of Arran and Baron Kilmarnock in the Peerage of Scotland and arrange Thomas' marriage to Princess Mary,...

, being made Earl of Arran

Earl of Arran

Earl of Arran is a title in both the Peerage of Scotland and the Peerage of Ireland. The two titles refer to different places, the Isle of Arran in Scotland, and the Aran Islands in Ireland...

and marrying the king's sister, Mary

Mary Stewart, Princess of Scotland

Princess Mary, Countess of Arran was the eldest daughter of King James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders. Her brother was King James III of Scotland. She married twice; firstly to Thomas Boyd, 1st Earl of Arran; secondly to James Hamilton, 1st Lord Hamilton...

. While Robert and Thomas were out of the country in 1469 the king asserted his control, executing members of the Boyd family. His foreign policy included a rapprochement with England, with his eldest son, the future James IV

James IV of Scotland

James IV was King of Scots from 11 June 1488 to his death. He is generally regarded as the most successful of the Stewart monarchs of Scotland, but his reign ended with the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Flodden Field, where he became the last monarch from not only Scotland, but also from all...

, being betrothed to Cecily of York

Cecily of York

Cecily of York, Viscountess Welles was an English Princess and the third, but eventual second surviving, daughter of Edward IV, King of England and his queen consort, née Lady Elizabeth Woodville, daughter of Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers.-Birth and Family:Cecily was born in Westminster Palace...

, the daughter of Edward IV of England

Edward IV of England

Edward IV was King of England from 4 March 1461 until 3 October 1470, and again from 11 April 1471 until his death. He was the first Yorkist King of England...

, a change of policy that was immensely unpopular at home. During the 1470s conflict developed between the king and his brothers, Alexander, Duke of Albany

Alexander Stewart, 1st Duke of Albany

Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany was the second son of King James II of Scotland, and his Queen consort Mary of Gueldres, daughter of Arnold, Duke of Gelderland.-Biography:...

and John, Earl of Mar

John Stewart, Earl of Mar (d. 1479)

John Stewart, Earl of Mar and Garioch was the youngest son of James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders.James II bestowed the titles of Earl of Mar and Earl of Garioch on his son sometime between 1458 and 1459. In 1479, John was accused of treason and imprisoned at Craigmillar Castle...

. Mar died suspiciously in 1480 and his estates were forfeited and possibly given to a royal favourite

Favourite

A favourite , or favorite , was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In medieval and Early Modern Europe, among other times and places, the term is used of individuals delegated significant political power by a ruler...

, Robert Cochrane. Albany fled to France in 1479, accused of treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

. By this point the alliance with England was failing and from 1480 there was intermittent war, followed by a full-scale invasion two years later, led by the Duke of Gloucester, the future Richard III

Richard III of England

Richard III was King of England for two years, from 1483 until his death in 1485 during the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty...

, and accompanied by Albany. James was imprisoned by his own subjects in Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a fortress which dominates the skyline of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, from its position atop the volcanic Castle Rock. Human habitation of the site is dated back as far as the 9th century BC, although the nature of early settlement is unclear...

, and Albany was established as lieutenant-general. Having taken Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed or simply Berwick is a town in the county of Northumberland and is the northernmost town in England, on the east coast at the mouth of the River Tweed. It is situated 2.5 miles south of the Scottish border....