Science and engineering in Manchester

Encyclopedia

Manchester

is one of the principal cities of the United Kingdom

, having gained city status

in 1853. Often regarded as the first industrialised city•

• , Manchester was a city built by the Industrial Revolution, in 1717 Manchester

was merely a market town of 10,000 people, but by 1911 it had a population of 2.3 million.

As its population and influence burgeoned, Manchester became a centre for new discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and technological developments in engineering. A famous but unattributed quote linked to Manchester is: "What Manchester does today, the rest of the world does tomorrow". Pioneering breakthrough's such as the first 'true' canal

which spawned 'Canal Mania

', the first intercity railway station which led to 'railway mania

' and the first stored-program computer

. The city has achieved great success in the field of physics, with the electron

(J. J. Thomson

, 1897), proton

(Rutherford

, 1917), neutron

(James Chadwick

, 1934) all being discovered by scientists educated in Manchester.

Famous scientists to have studied in Manchester include John Dalton

, James Prescott Joule

, J. J. Thomson

, Ernest Rutherford

, James Chadwick

and Alan Turing

. A creative and often seen as a bohemian

city, Manchester also has the highest number of patent applications per head of population in the United Kingdom in 2003. The city is served by the University of Manchester

, previously UMIST and the Victoria University of Manchester

pre-2004. The university has a total of 25 Nobel Laureates, only the selective Oxbridge universities have more Nobel laureates. The city is also served by the Museum of Science and Industry celebrating Mancunian, as well as national achievements in both fields.

In 1630, astronomer William Crabtree

In 1630, astronomer William Crabtree

observed the transit of Venus

. Crabtree was born in the hamlet

of "Broughton Spout" which was on the east bank of the River Irwell

, near the area now known as "The Priory" in Broughton and was educated at The Manchester Grammar School. He married into a wealthy family and worked as a merchant in Manchester. However, in his spare time, his great interest was astronomy

. He carefully measured the movements of the planets and undertook precise astronomical calculations. With improved accuracy, he rewrote the existing Rudolphine Tables

of Planetary Positions.

Crabtree corresponded with Jeremiah Horrocks

(who sometimes spelt his name in the Latised form as Horrox), another enthusiastic amateur astronomer, from 1636. A group of astronomers from the north of England, which included William Gascoigne

, formed around them and were Britain's first followers of the astronomy of Johannes Kepler

. "Nos Keplari" as the group called themselves, were distinguished as being the first people to gain a realistic notion of the solar system's size. Crabtree and Horrocks were the only astronomers to observe, plot, and record the transit of the planet Venus

across the Sun

, as predicted by Horrocks, on 24 November 1639 (Julian calendar

, or 4 December in the Gregorian calendar

). They also predicted the next occurrence on 8 June 2004. The two correspondents both recorded the event in their own homes and it is not known whether they ever met in person, but Crabtree's calculations were crucial in allowing Horrocks to estimate the size of Venus

and the distance from the Earth

to the Sun. Unfortunately Horrocks died early in 1641 the day before he was due to meet Crabtree. Crabtree made his will on 19 July 1644, and was buried within the precincts of the Manchester Collegiate Church on 1 August 1644, close to where he had received his education.

The Bridgewater Canal

The Bridgewater Canal

, opening in 1761 is generally regarded as the earliest successful canals. The Bridgewater Canal connects Runcorn

, Manchester

and Leigh

, in North West England

. It was commissioned by Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater

, to transport coal from his mines in Worsley

to Manchester. It was opened in 1761 from Worsley to Manchester, and later extended from Manchester to Runcorn, and then from Worsley to Leigh.

The Duke invested a large sum of money in the scheme. From Worsley to Manchester its construction cost £168,000 (£ as of ), but its advantages over land and river transport meant that within a year of its opening in 1761, the price of coal in Manchester fell by about half. This success helped inspire a period of intense canal building, known as Canal Mania

. Along with its stone aqueduct at Barton-upon-Irwell, the Bridgewater Canal was considered a major engineering achievement. One commentator wrote that when finished, "[the canal] will be the most extraordinary thing in the Kingdom, if not in Europe. The boats in some places are to go underground, and in other places over a navigable river, without communicating with its waters ...".

John Dalton

John Dalton

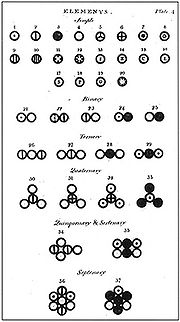

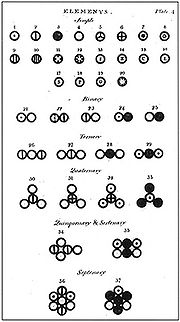

, was born in Cumberland

in 1766, a promising young scientist he moved to Manchester in 1793. He hypothesised the idea of "colour blindness", a theory which was alien to all as it had not been formally talked about before. Dalton hypothesised the idea from his own experience, as he suffered from discoloured eyesight himself. Dalton would go on to propose the Dalton Atomic Theory in which he hypothesised that elements were made of small particles called atoms.

Manchester Liverpool Road is a former railway station on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Manchester Liverpool Road is a former railway station on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

in Manchester

, England

which opened on 15 September 1830. The L&MR station was the terminus of the world's first inter-city

passenger railway in which all services were hauled by timetabled steam locomotive

s. It is now the world's oldest surviving terminal railway station. The station closed to passenger services on 4 May 1844 when the line was extended to join the Manchester and Leeds Railway

at Hunt's Bank. Liverpool Road was superseded by Manchester Victoria railway station

. Since Liverpool Road ceased operation, the oldest railway station still in use is Earlestown railway station

at Newton-le-Willows

which also opened on 15 September 1830. However the station is still preserved by the Museum of Science and Industry

.

Robert Angus Smith

, a Scottish chemist visited Manchester in the 1840s. In his research in Manchester, Smith discovered the existence of acid rain

, a by product of the industrial revolution. Smith consequently pushed for greater environmental awareness and helped to found the Noxious Vapours Abatement Society in Manchester, which raised awareness of the consequences of poor air.

was a engineer and inventor who hailed from Stockport, Cheshire (now Greater Manchester). A talented mechanic amongst various other engineering roles, for long periods of his life, he worked in factories in Manchester. Whitworth would ultimately devise a standard screw thread

system, the first of it's kind in the world. The system he created in 1841 would become known as the British Standard Whitworth

.

Whitworth also invented the Whitworth rifle

, which was a giant leap in the development of the rifle

, delivering a shooting range which far exceeded any firearm available at the time. In the American Civil War

Confederate troops equipped with barrel-length three power scopes mounted on the exceptionally accurate Whitworth rifle

had been known to kill Union officers at ranges of about 800 yards (731.5m), an unheard-of distance at that time. Consequently, the Whitworth rifle is considered one of the earliest examples of a sniper rifle

, if not the first. In recognition of his achievements, a number of buildings in Manchester are named after him as is Whitworth Street

. As part of his bequest, the Whitworth Art Gallery

was created in his honour.

, who arranged a meeting at his home, The Towers

in Didsbury

, on 27 June 1882. He invited the representatives of several Lancashire

towns, local businessmen and politicians, and two civil engineers: Hamilton Fulton

and Edward Leader Williams

. Fulton's design was for a tidal canal, with no locks and a deepened channel into Manchester. With the city about 60 feet (18.3 m) above sea level, the docks and quays would have been well below the surrounding surface. Williams' plan was to dredge a channel between a set of retaining walls, and build a series of locks

and sluice

s to lift incoming vessels up to Manchester. Both engineers were invited to submit their proposals, and Williams' plans were selected to form the basis of a bill to be submitted to Parliament later that year. The Manchester Ship Canal briefly became the longest ship canal in the world upon opening and at its peak in the 1960s, it was the third busiest port in Britain.

bought the 1183 acres (4,787,435.4 m²) country estate belonging to Sir Humphrey Francis de Trafford

for £360,000 (£ as of ). Hooley intended to develop the site, which was close to Manchester and at the end of the canal, as an exclusive housing estate, screened by woods from industrial units constructed along the 1.5 miles (2.4 km) frontage onto the canal.

With the predicted traffic for the canal slow to materialise, Hooley and Marshall Stevens

(the general manager of the Ship Canal Company) came to see the benefits that the industrial development of Trafford Park could offer to both the ship canal and the estate. In January 1897 Stevens became the managing director of Trafford Park Estates, where he remained until 1930, latterly as its joint chairman and managing director.

Within five years Trafford Park, Europe's largest industrial estate, was home to forty firms. The earliest structures on the canal side were grain silos; the grain was used for flour and as ballast

for ships carrying raw cotton

. The wooden silo built opposite No.9 Dock in 1898 (destroyed in the Manchester Blitz

in 1940) was Europe's largest grain elevator. The CWS bought land on Trafford Wharf in 1903, where it opened a bacon factory and a flour mill. In 1906 it bought the Sun Mill, which it extended in 1913 to create the UK's largest flour mill, with its own wharf, elevators and silos.

Inland from the canal the British Westinghouse Electric Company

bought 11 per cent of the estate. Westinghouse's American architect Charles Heathcote

was responsible for much of the planning and design of their factory, which built steam turbine

s and turbo generator

s. By 1899 Heathcote had also designed fifteen warehouses for the Manchester Ship Canal Company. Engineering companies such as Ford and Metropolitan Vickers had a large presence at Trafford Park alongside non-engineering companies such Kellogg's who remain to this day. Trafford Park was also home to the first Ford production plant for their revolutionary Model T car outside of the United States

.

During World War II, Trafford Park became an important centre for the manufacture and development in engineering in the aim of giving Britain a technological advantage over its enemies. Having an abandoned factory in Trafford Park

During World War II, Trafford Park became an important centre for the manufacture and development in engineering in the aim of giving Britain a technological advantage over its enemies. Having an abandoned factory in Trafford Park

, Ford of Britain

was approached about the possibility of converting it into an aircraft engine production unit by Herbert Austin

, who was in charge of the shadow factory plan. Building work on a new factory was started in May 1940 on a 118 acres (47.8 ha) site, while Ford engineers went on a fact finding mission to Derby. Their chief engineer commented to Sir Stanley Hooker that the tolerances used were far too wide for them, and so the 20,000 drawings would need to be redrawn to Ford tolerance levels, which took over a year. Ford's factory was built with two distinct sections to minimise potential bomb damage, it was completed in May 1941 and bombed in the same month. At first, the factory had difficulty in attracting suitable labour, and large numbers of women, youths and untrained men had to be taken on. Despite this, the first Merlin engine came off the production line one month later and it was building the engine at a rate of 200 per week by 1943, at which point the joint factories were producing 18,000 Merlins per year. Ford’s investment in machinery and the redesign resulted in the 10,000 man-hours needed to produce a Merlin dropping to 2,727 in three years, while unit cost fell from £6,540 in June 1941 to £1,180 by the war’s end. In his autobiography Not much of an Engineer, Sir Stanley Hooker states: "... once the great Ford factory at Manchester started production, Merlins came out like shelling peas. The percentage of engines rejected by the Air Ministry was zero. Not one engine of the 30,400 produced was rejected ...". Some 17,316 people worked at the Trafford Park plant, including 7,260 women and two resident doctors and nurses. Merlin production started to run down in August 1945, and finally ceased on 23 March 1946.

The Ship Canal is now past its heyday, but still sits at Europe's largest industrial estate, Trafford Park

and there are plans to increase shipping. Its importance highlighted by the engineering achievement that was the Manchester Ship Canal, the only ship canal

in Britain and growth of the first industrial estate in the world in Trafford Park

.

. The 'Nuclear Family' was the alias given to a group of scientists who studied nuclear physics in Manchester. 'Family' highlights the consistent development through the generations in nuclear physics, beginning with Thomson in the late 18th century and ending with James Chadwick

in the 1930s who discovered the neutron

. Ernest Rutherford is often described as the 'father of nuclear physics', equally the same could be said of J. J. Thomson who discovered the electron and isotopes, and ultimately taught Rutherford who later go on to split the atom. Scientists who were part of the 'nuclear family' in Manchester included J. J. Thomson

, Ernest Rutherford

, Niels Bohr

, Hans Geiger, Ernest Marsden

, John Cockcroft

and James Chadwick

.

J. J. Thomson, a Manchester-born physicist hailing from Cheetham Hill

, who enrolled to Owens College as a 14-year-old. Thomson would go on to discover the electron

in 1897 and isotope

, as well as inventing the mass spectrometer. All of which, contributed to his award of the Nobel Prize in Physics

in 1906. Thomson also proposed the plum pudding model, which was later confirmed as scientifically incorrect by Rutherford.

In 1907, Ernest Rutherford, a scientist who had been taught by Thomson at the University of Cambridge

, moved to Manchester to become chair of physics at the Victoria University of Manchester

. Rutherford hypothesised the Rutherford model

, which was later improved on by Niels Bohr who proposed the Bohr model

. Rutherford would later have a great influence on students such as Niels Bohr

, Hans Geiger, Ernest Marsden

and James Chadwick

. Rutherford's main work would come in 1917 when he would 'split the atom

'.

From the advent of aviation at the beginning of the 20th century, Manchester has been home to a number of famous aviation companies, most notably Avro

From the advent of aviation at the beginning of the 20th century, Manchester has been home to a number of famous aviation companies, most notably Avro

.

In 1910, French aviator Louis Paulhan

flew from London to Manchester in approximately 12 hours. Paulhan won the first Daily Mail aviation prizes

who offered the prize in 1906.

Jack Alcock was born on 5 November 1892 at Seymour Grove, Old Trafford

, Stretford

, England

. He attended St Thomas's primary school in Heaton Chapel

, Stockport

. He first became interested in flying at the age of seventeen. In 1910 he became an assistant to Works Manager Charles Fletcher, an early Manchester aviator and Norman Crossland, a motor engineer and founder of Manchester Aero Club. It was during this period that Alcock met the Frenchman Maurice Ducrocq who was both a demonstration pilot and UK sales representative for aero engines made by Spirito Mario Viale in Italy.

Ducrocq took Alcock on as a mechanic at the Brooklands

aerodrome, Surrey, where he learned to fly at Ducrocq's flying school, gaining his pilot's licence there in November 1912. By summer 1914 he was proficient enough to compete in a Hendon-Birmingham-Manchester and return air race, flying a Farman

biplane. He landed at Trafford Park Aerodrome

and flew back to Hendon the same day. Alcock became an experienced military pilot and instructor during World War I

with the Royal Naval Air Service

, although he was shot down during a bombing raid and taken prisoner in Turkey

.

After the war, Alcock wanted to continue his flying career and took up the challenge of attempting to be the first to fly directly across the Atlantic. Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown

took off from St John's, Newfoundland, at 1:45 pm local time on 14 June 1919, and landed in Derrygimla bog near Clifden, Ireland, 16 hours and 12 minutes later on 15 June 1919 after flying 1,980 miles (3,186 km). The flight had been much affected by bad weather, making accurate navigation difficult; the intrepid duo also had to cope with turbulence, instrument failure and ice on the wings. The flight was made in a modified Vickers Vimy

bomber, and won a £10,000 prize

offered by London's Daily Mail

newspaper for the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic. His grave in Southern Cemetery, Manchester

is marked by a large stone memorial alongside other famous Mancunian figures. He is buried in grave space "Church of England, Section G, Grave Number 966", alongside 4 other individuals: John Alcock, Mary Alcock, Edward Samson Alcock and Elsie Moseley.

In 1910, Eccles-born Alliott Verdon Roe

founded Avro on at Brownsfield Mill on Great Ancoats Street in Manchester city centre

. Alongside, Farnworth

-born aircraft designer Roy Chadwick

, Avro would go on to design some recognisable British aircraft of the 20th century. The Avro Lancaster bomber, devised for World War II was a redeveloped version of the Avro Manchester

and subsequently became the most important British aircraft of the war alongside the Supermarine Spitfire

.

In the 1930s, Bernard Lovell

In the 1930s, Bernard Lovell

, an astronomer moved to Manchester to become a research fellow on the cosmic ray research team at the Victoria University of Manchester

. He spent war time years working on developing radar systems and the like to assist in the war effort. After the war, he continued his studies in cosmic rays, but background radiation and light in the large Manchester impeded his work. He decided to push for funding for a large radio telescope which would be based away from the city on the Cheshire Plain

south of Manchester at the Jodrell Bank Observatory.

Funding was granted from the Nuffield Foundation

with some contribution from the government, and soon a 89 metre height structure, which was the largest telescope in the world at the time of construction, was operational in 1957.

The telescope became operational in October 1957, which was just before the launch of Sputnik 1

, the world's first artificial satellite. Only the Soviet hierarchy were aware of Sputnik and it was the Lovell Telescope which tracked the satellite. While the transmissions from Sputnik itself could easily be picked up by a household radio

, the Lovell Telescope was the only telescope capable of tracking Sputnik's booster rocket by radar; it first located it just before midnight on 12 October 1957. It also located Sputnik 2

's carrier rocket at just after midnight on 16 November 1957. Jodrell Bank continued tracking new artificial satellites in the following years, and also doubled up as a long range ballistic missile radar system, a beneficial trait which helped the telescope gain funding from the British government. The Jodrell Bank Observatory is currently operated by the University of Manchester and was nominated for UNESCO World Heritage Status in 2011.

returned to Manchester to head the Electrical Engineering department at the the Victoria University of Manchester. Williams also recruited Tom Kilburn

, with whom he worked with at the Telecommunications Research Establishment

during World War II. Both worked on perfecting the cathode ray tube

which Kilburn worked on. They eventually came up with the Williams tube

, which allowed the storage of binary data. Consequently both worked on the Manchester Small-Scale Experimental Machine, nicknamed the 'Manchester Baby' and on the 21 June 1948, the Machine was switched on. Despite its low performance by modern standards - the 'baby' only had a 32-bit word length and a memory of 32 words - it was the first computer capable of storing data in the world and was breakthrough in the computer science world.

The 'Baby' had provided a feasible design and development began on a more, usable and practical computer in the Manchester Mark 1

. Joined by Alan Turing

, the university continued development and by October 1949, the Mark 1 was finished. The computer ran successfully, error-free, on the 16 and 17 June 1949. Thirty-five patents resulted from the computer and the successful implementation of an index register

.

, the world's first baby conceived by in vitro fertilisation

. Louise Brown

, was born at on 1978 at the Oldham General Hospital and made medical history: in vitro fertilization meant a new way to help infertile couples who formerly had no possibility of having a baby.

Refinements in technology have increased pregnancy rates and it is estimated that in 2010 about children have been born by IVF with approximately 170,000 coming from donated oocyte

and embryos In 2010, Robert G. Edwards was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

"for the development of in vitro fertilization".

and Konstantin Novoselov

, physicists at the University of Manchester

won the Nobel Prize in Physics

for their work on graphene

. Successfully isolated in 2004, research and development continues on the 'miracle material' today to find practical, everyday uses for the material. The following year in 2011, the British government announced £50 million of funding to allow further development of graphene in the United Kingdom.

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

is one of the principal cities of the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, having gained city status

City status in the United Kingdom

City status in the United Kingdom is granted by the British monarch to a select group of communities. The holding of city status gives a settlement no special rights other than that of calling itself a "city". Nonetheless, this appellation carries its own prestige and, consequently, competitions...

in 1853. Often regarded as the first industrialised city•

• , Manchester was a city built by the Industrial Revolution, in 1717 Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

was merely a market town of 10,000 people, but by 1911 it had a population of 2.3 million.

As its population and influence burgeoned, Manchester became a centre for new discoveries, scientific breakthroughs and technological developments in engineering. A famous but unattributed quote linked to Manchester is: "What Manchester does today, the rest of the world does tomorrow". Pioneering breakthrough's such as the first 'true' canal

Bridgewater Canal

The Bridgewater Canal connects Runcorn, Manchester and Leigh, in North West England. It was commissioned by Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, to transport coal from his mines in Worsley to Manchester...

which spawned 'Canal Mania

Canal Mania

Canal Mania is a term used to describe an intense period of canal building in England and Wales between the 1790s and 1810s, and the speculative frenzy that accompanied it in the early 1790s.-Background:...

', the first intercity railway station which led to 'railway mania

Railway Mania

The Railway Mania was an instance of speculative frenzy in Britain in the 1840s. It followed a common pattern: as the price of railway shares increased, more and more money was poured in by speculators, until the inevitable collapse...

' and the first stored-program computer

Stored-program computer

A stored-program computer is one which stores program instructions in electronic memory. Often the definition is extended with the requirement that the treatment of programs and data in memory be interchangeable or uniform....

. The city has achieved great success in the field of physics, with the electron

Electron

The electron is a subatomic particle with a negative elementary electric charge. It has no known components or substructure; in other words, it is generally thought to be an elementary particle. An electron has a mass that is approximately 1/1836 that of the proton...

(J. J. Thomson

J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John "J. J." Thomson, OM, FRS was a British physicist and Nobel laureate. He is credited for the discovery of the electron and of isotopes, and the invention of the mass spectrometer...

, 1897), proton

Proton

The proton is a subatomic particle with the symbol or and a positive electric charge of 1 elementary charge. One or more protons are present in the nucleus of each atom, along with neutrons. The number of protons in each atom is its atomic number....

(Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

, 1917), neutron

Neutron

The neutron is a subatomic hadron particle which has the symbol or , no net electric charge and a mass slightly larger than that of a proton. With the exception of hydrogen, nuclei of atoms consist of protons and neutrons, which are therefore collectively referred to as nucleons. The number of...

(James Chadwick

James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick CH FRS was an English Nobel laureate in physics awarded for his discovery of the neutron....

, 1934) all being discovered by scientists educated in Manchester.

Famous scientists to have studied in Manchester include John Dalton

John Dalton

John Dalton FRS was an English chemist, meteorologist and physicist. He is best known for his pioneering work in the development of modern atomic theory, and his research into colour blindness .-Early life:John Dalton was born into a Quaker family at Eaglesfield, near Cockermouth, Cumberland,...

, James Prescott Joule

James Prescott Joule

James Prescott Joule FRS was an English physicist and brewer, born in Salford, Lancashire. Joule studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work . This led to the theory of conservation of energy, which led to the development of the first law of thermodynamics. The...

, J. J. Thomson

J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John "J. J." Thomson, OM, FRS was a British physicist and Nobel laureate. He is credited for the discovery of the electron and of isotopes, and the invention of the mass spectrometer...

, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

, James Chadwick

James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick CH FRS was an English Nobel laureate in physics awarded for his discovery of the neutron....

and Alan Turing

Alan Turing

Alan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS , was an English mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, and computer scientist. He was highly influential in the development of computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which played a...

. A creative and often seen as a bohemian

Bohemianism

Bohemianism is the practice of an unconventional lifestyle, often in the company of like-minded people, with few permanent ties, involving musical, artistic or literary pursuits...

city, Manchester also has the highest number of patent applications per head of population in the United Kingdom in 2003. The city is served by the University of Manchester

University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public research university located in Manchester, United Kingdom. It is a "red brick" university and a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive British universities and the N8 Group...

, previously UMIST and the Victoria University of Manchester

Victoria University of Manchester

The Victoria University of Manchester was a university in Manchester, England. On 1 October 2004 it merged with the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology to form a new entity, "The University of Manchester".-1851 - 1951:The University was founded in 1851 as Owens College,...

pre-2004. The university has a total of 25 Nobel Laureates, only the selective Oxbridge universities have more Nobel laureates. The city is also served by the Museum of Science and Industry celebrating Mancunian, as well as national achievements in both fields.

17th century

William Crabtree

William Crabtree was an astronomer, mathematician, and merchant from Broughton, then a township near Manchester, which is now part of Salford, Greater Manchester, England...

observed the transit of Venus

Transit of Venus

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth, becoming visible against the solar disk. During a transit, Venus can be seen from Earth as a small black disk moving across the face of the Sun...

. Crabtree was born in the hamlet

Hamlet (place)

A hamlet is usually a rural settlement which is too small to be considered a village, though sometimes the word is used for a different sort of community. Historically, when a hamlet became large enough to justify building a church, it was then classified as a village...

of "Broughton Spout" which was on the east bank of the River Irwell

River Irwell

The River Irwell is a long river which flows through the Irwell Valley in the counties of Lancashire and Greater Manchester in North West England. The river's source is at Irwell Springs on Deerplay Moor, approximately north of Bacup, in the parish of Cliviger, Lancashire...

, near the area now known as "The Priory" in Broughton and was educated at The Manchester Grammar School. He married into a wealthy family and worked as a merchant in Manchester. However, in his spare time, his great interest was astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

. He carefully measured the movements of the planets and undertook precise astronomical calculations. With improved accuracy, he rewrote the existing Rudolphine Tables

Rudolphine Tables

The Rudolphine Tables consist of a star catalogue and planetary tables published by Johannes Kepler in 1627 using data from Tycho Brahe's observations.-Previous tables:...

of Planetary Positions.

Crabtree corresponded with Jeremiah Horrocks

Jeremiah Horrocks

Jeremiah Horrocks , sometimes given as Jeremiah Horrox , was an English astronomer who was the only person to predict, and one of only two people to observe and record, the transit of Venus of 1639.- Life and work :Horrocks was born in Lower Lodge, in...

(who sometimes spelt his name in the Latised form as Horrox), another enthusiastic amateur astronomer, from 1636. A group of astronomers from the north of England, which included William Gascoigne

William Gascoigne (scientist)

William Gascoigne was an English astronomer, mathematician and maker of scientific instruments from Middleton near Leeds who invented the micrometer...

, formed around them and were Britain's first followers of the astronomy of Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican...

. "Nos Keplari" as the group called themselves, were distinguished as being the first people to gain a realistic notion of the solar system's size. Crabtree and Horrocks were the only astronomers to observe, plot, and record the transit of the planet Venus

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, orbiting it every 224.7 Earth days. The planet is named after Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty. After the Moon, it is the brightest natural object in the night sky, reaching an apparent magnitude of −4.6, bright enough to cast shadows...

across the Sun

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is almost perfectly spherical and consists of hot plasma interwoven with magnetic fields...

, as predicted by Horrocks, on 24 November 1639 (Julian calendar

Julian calendar

The Julian calendar began in 45 BC as a reform of the Roman calendar by Julius Caesar. It was chosen after consultation with the astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria and was probably designed to approximate the tropical year .The Julian calendar has a regular year of 365 days divided into 12 months...

, or 4 December in the Gregorian calendar

Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar, also known as the Western calendar, or Christian calendar, is the internationally accepted civil calendar. It was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII, after whom the calendar was named, by a decree signed on 24 February 1582, a papal bull known by its opening words Inter...

). They also predicted the next occurrence on 8 June 2004. The two correspondents both recorded the event in their own homes and it is not known whether they ever met in person, but Crabtree's calculations were crucial in allowing Horrocks to estimate the size of Venus

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, orbiting it every 224.7 Earth days. The planet is named after Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty. After the Moon, it is the brightest natural object in the night sky, reaching an apparent magnitude of −4.6, bright enough to cast shadows...

and the distance from the Earth

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun, and the densest and fifth-largest of the eight planets in the Solar System. It is also the largest of the Solar System's four terrestrial planets...

to the Sun. Unfortunately Horrocks died early in 1641 the day before he was due to meet Crabtree. Crabtree made his will on 19 July 1644, and was buried within the precincts of the Manchester Collegiate Church on 1 August 1644, close to where he had received his education.

The creation of the first economically successful canal

Bridgewater Canal

The Bridgewater Canal connects Runcorn, Manchester and Leigh, in North West England. It was commissioned by Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, to transport coal from his mines in Worsley to Manchester...

, opening in 1761 is generally regarded as the earliest successful canals. The Bridgewater Canal connects Runcorn

Runcorn

Runcorn is an industrial town and cargo port within the borough of Halton in the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. In 2009, its population was estimated to be 61,500. The town is on the southern bank of the River Mersey where the estuary narrows to form Runcorn Gap. Directly to the north...

, Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

and Leigh

Leigh, Greater Manchester

Leigh is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, in Greater Manchester, England. It is southeast of Wigan, and west of Manchester. Leigh is situated on low lying land to the north west of Chat Moss....

, in North West England

North West England

North West England, informally known as The North West, is one of the nine official regions of England.North West England had a 2006 estimated population of 6,853,201 the third most populated region after London and the South East...

. It was commissioned by Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater

Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater

Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater , known as Lord Francis Egerton until 1748, was a British nobleman, the younger son of the 1st Duke...

, to transport coal from his mines in Worsley

Worsley

Worsley is a town in the metropolitan borough of the City of Salford, in Greater Manchester, England. It lies along the course of Worsley Brook, west of Manchester. The M60 motorway bisects the area....

to Manchester. It was opened in 1761 from Worsley to Manchester, and later extended from Manchester to Runcorn, and then from Worsley to Leigh.

The Duke invested a large sum of money in the scheme. From Worsley to Manchester its construction cost £168,000 (£ as of ), but its advantages over land and river transport meant that within a year of its opening in 1761, the price of coal in Manchester fell by about half. This success helped inspire a period of intense canal building, known as Canal Mania

Canal Mania

Canal Mania is a term used to describe an intense period of canal building in England and Wales between the 1790s and 1810s, and the speculative frenzy that accompanied it in the early 1790s.-Background:...

. Along with its stone aqueduct at Barton-upon-Irwell, the Bridgewater Canal was considered a major engineering achievement. One commentator wrote that when finished, "[the canal] will be the most extraordinary thing in the Kingdom, if not in Europe. The boats in some places are to go underground, and in other places over a navigable river, without communicating with its waters ...".

19th century

John Dalton

John Dalton FRS was an English chemist, meteorologist and physicist. He is best known for his pioneering work in the development of modern atomic theory, and his research into colour blindness .-Early life:John Dalton was born into a Quaker family at Eaglesfield, near Cockermouth, Cumberland,...

, was born in Cumberland

Cumberland

Cumberland is a historic county of North West England, on the border with Scotland, from the 12th century until 1974. It formed an administrative county from 1889 to 1974 and now forms part of Cumbria....

in 1766, a promising young scientist he moved to Manchester in 1793. He hypothesised the idea of "colour blindness", a theory which was alien to all as it had not been formally talked about before. Dalton hypothesised the idea from his own experience, as he suffered from discoloured eyesight himself. Dalton would go on to propose the Dalton Atomic Theory in which he hypothesised that elements were made of small particles called atoms.

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world's first inter-city passenger railway in which all the trains were timetabled and were hauled for most of the distance solely by steam locomotives. The line opened on 15 September 1830 and ran between the cities of Liverpool and Manchester in North...

in Manchester

Manchester

Manchester is a city and metropolitan borough in Greater Manchester, England. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 2010 mid-year population estimate for Manchester was 498,800. Manchester lies within one of the UK's largest metropolitan areas, the metropolitan county of Greater...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

which opened on 15 September 1830. The L&MR station was the terminus of the world's first inter-city

Inter-city rail

Inter-city rail services are express passenger train services that cover longer distances than commuter or regional trains.There is no precise definition of inter-city rail. Its meaning may vary from country to country...

passenger railway in which all services were hauled by timetabled steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

s. It is now the world's oldest surviving terminal railway station. The station closed to passenger services on 4 May 1844 when the line was extended to join the Manchester and Leeds Railway

Manchester and Leeds Railway

The Manchester and Leeds Railway was a railway company in the United Kingdom which opened in 1839, connecting Manchester with Leeds via the North Midland Railway which it joined at Normanton....

at Hunt's Bank. Liverpool Road was superseded by Manchester Victoria railway station

Manchester Victoria station

Manchester Victoria station in Manchester, England is the city's second largest mainline railway station. It is also a Metrolink station, one of eight within the City Zone...

. Since Liverpool Road ceased operation, the oldest railway station still in use is Earlestown railway station

Earlestown railway station

Earlestown railway station is a railway station in Earlestown, Newton-le-Willows in Merseyside, England. Since recent restoration of a platform for Warrington Bank Quay to Liverpool trains, it is one of the few "triangular" stations in Britain ....

at Newton-le-Willows

Earlestown

Earlestown forms the western part of Newton-le-Willows, a town in the Metropolitan Borough of St Helens, in Merseyside, England. At the 2001 Census the population was recorded as 10,274.-History:...

which also opened on 15 September 1830. However the station is still preserved by the Museum of Science and Industry

Museum of Science and Industry

MOSI may refer to:* MoSi — molybdenum silicide, an important material in the semiconductor industry* MOSI - Master Out Slave In, a signal on the Serial Peripheral Interface Bus* MOSI protocol, an extension of the basic MSI cache coherency protocol...

.

Robert Angus Smith

Robert Angus Smith

Robert Angus Smith was a Scottish chemist, who investigated numerous environmental issues. He is famous for his research on air pollution in 1852, in the course of which he discovered what came to be known as acid rain...

, a Scottish chemist visited Manchester in the 1840s. In his research in Manchester, Smith discovered the existence of acid rain

Acid rain

Acid rain is a rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it possesses elevated levels of hydrogen ions . It can have harmful effects on plants, aquatic animals, and infrastructure. Acid rain is caused by emissions of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen...

, a by product of the industrial revolution. Smith consequently pushed for greater environmental awareness and helped to found the Noxious Vapours Abatement Society in Manchester, which raised awareness of the consequences of poor air.

Joseph Whitworth

Joseph WhitworthJoseph Whitworth

Sir Joseph Whitworth, 1st Baronet was an English engineer, entrepreneur, inventor and philanthropist. In 1841, he devised the British Standard Whitworth system, which created an accepted standard for screw threads...

was a engineer and inventor who hailed from Stockport, Cheshire (now Greater Manchester). A talented mechanic amongst various other engineering roles, for long periods of his life, he worked in factories in Manchester. Whitworth would ultimately devise a standard screw thread

Screw thread

A screw thread, often shortened to thread, is a helical structure used to convert between rotational and linear movement or force. A screw thread is a ridge wrapped around a cylinder or cone in the form of a helix, with the former being called a straight thread and the latter called a tapered thread...

system, the first of it's kind in the world. The system he created in 1841 would become known as the British Standard Whitworth

British Standard Whitworth

British Standard Whitworth is one of a number of imperial unit based screw thread standards which use the same bolt heads and nut hexagonal sizes, the others being British Standard Fine thread and British Standard Cycle...

.

Whitworth also invented the Whitworth rifle

Whitworth rifle

The Whitworth Rifle was a single-shot muzzle-loaded rifle used in the last half of the 19th century.-History:The Whitworth rifle was designed by Sir Joseph Whitworth, a prominent British engineer and entrepreneur. Whitworth had experimented with cannons using twisted hexagonal barrels instead of...

, which was a giant leap in the development of the rifle

Rifle

A rifle is a firearm designed to be fired from the shoulder, with a barrel that has a helical groove or pattern of grooves cut into the barrel walls. The raised areas of the rifling are called "lands," which make contact with the projectile , imparting spin around an axis corresponding to the...

, delivering a shooting range which far exceeded any firearm available at the time. In the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

Confederate troops equipped with barrel-length three power scopes mounted on the exceptionally accurate Whitworth rifle

Whitworth rifle

The Whitworth Rifle was a single-shot muzzle-loaded rifle used in the last half of the 19th century.-History:The Whitworth rifle was designed by Sir Joseph Whitworth, a prominent British engineer and entrepreneur. Whitworth had experimented with cannons using twisted hexagonal barrels instead of...

had been known to kill Union officers at ranges of about 800 yards (731.5m), an unheard-of distance at that time. Consequently, the Whitworth rifle is considered one of the earliest examples of a sniper rifle

Sniper rifle

In military and law enforcement terminology, a sniper rifle is a precision-rifle used to ensure more accurate placement of bullets at longer ranges than other small arms. A typical sniper rifle is built for optimal levels of accuracy, fitted with a telescopic sight and chambered for a military...

, if not the first. In recognition of his achievements, a number of buildings in Manchester are named after him as is Whitworth Street

Whitworth Street

Whitworth Street is a street in Manchester, England. It runs between London Road and Oxford Street . West of Oxford Street it becomes Whitworth Street West which then goes as far as Deansgate . It was opened in 1899 and is lined with many large and grand warehouses. It is named after the engineer...

. As part of his bequest, the Whitworth Art Gallery

Whitworth Art Gallery

The Whitworth Art Gallery is an art gallery in Manchester, England, containing about 55,000 items in its collection. The museum is located south of the Manchester University campus, in Whitworth Park....

was created in his honour.

Manchester Ship Canal

In the 1880s, plans for a new Manchester Ship Canal were proposed. The idea was championed by Manchester manufacturer Daniel AdamsonDaniel Adamson

Daniel Adamson was a notable English engineer who became a successful manufacturer of boilers and was the driving force behind the inception of the Manchester Ship Canal project during the 1880s.-Early life:...

, who arranged a meeting at his home, The Towers

The Towers (Manchester)

The Towers is a research establishment for new technologies in cotton production. The Shirley Institute was established in 1920 at a cost of £10,000 to accommodate the newly formed British Cotton Industry Research Association...

in Didsbury

Didsbury

Didsbury is a suburban area of the City of Manchester, in Greater Manchester, England. It lies on the north bank of the River Mersey, south of Manchester city centre, in the southern half of the Greater Manchester Urban Area...

, on 27 June 1882. He invited the representatives of several Lancashire

Lancashire

Lancashire is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in the North West of England. It takes its name from the city of Lancaster, and is sometimes known as the County of Lancaster. Although Lancaster is still considered to be the county town, Lancashire County Council is based in Preston...

towns, local businessmen and politicians, and two civil engineers: Hamilton Fulton

Hamilton Fulton

Hamilton Fulton was a British engineer who later immigrated to North Carolina.He was born in Great Britain, presumably of Scottish parentage, and had studied under the noted Scottish Engineer, John Rennie, the designer of London Bridge...

and Edward Leader Williams

Edward Leader Williams

Sir Edward Leader Williams was an English civil engineer, chiefly remembered as the designer of the Manchester Ship Canal, but also heavily involved in other canal projects in north Cheshire.-Early life:...

. Fulton's design was for a tidal canal, with no locks and a deepened channel into Manchester. With the city about 60 feet (18.3 m) above sea level, the docks and quays would have been well below the surrounding surface. Williams' plan was to dredge a channel between a set of retaining walls, and build a series of locks

Lock (water transport)

A lock is a device for raising and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on river and canal waterways. The distinguishing feature of a lock is a fixed chamber in which the water level can be varied; whereas in a caisson lock, a boat lift, or on a canal inclined plane, it is...

and sluice

Sluice

A sluice is a water channel that is controlled at its head by a gate . For example, a millrace is a sluice that channels water toward a water mill...

s to lift incoming vessels up to Manchester. Both engineers were invited to submit their proposals, and Williams' plans were selected to form the basis of a bill to be submitted to Parliament later that year. The Manchester Ship Canal briefly became the longest ship canal in the world upon opening and at its peak in the 1960s, it was the third busiest port in Britain.

Trafford Park

As the ship canal was opened in 1894, plans were afoot for a new industrial estate, the first of its kind in the world. Two years after the opening of the ship canal, financier Ernest Terah HooleyErnest Terah Hooley

Ernest Terah Hooley was an English financier and developer of the Trafford Park industrial estate in the outskirts of Manchester.-Biography:...

bought the 1183 acres (4,787,435.4 m²) country estate belonging to Sir Humphrey Francis de Trafford

Sir Humphrey de Trafford, 3rd Baronet

Sir Humphrey Francis de Trafford was an English landowner and racehorse breeder. He was the son of Sir Humphrey de Trafford, 2nd Baronet and Lady Annette Mary Talbot....

for £360,000 (£ as of ). Hooley intended to develop the site, which was close to Manchester and at the end of the canal, as an exclusive housing estate, screened by woods from industrial units constructed along the 1.5 miles (2.4 km) frontage onto the canal.

With the predicted traffic for the canal slow to materialise, Hooley and Marshall Stevens

Marshall Stevens

Marshall Stevens was an English property developer. His work with Daniel Adamson and others led to the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal, completed in 1894, and he was appointed general manager of the Ship Canal Company in 1891...

(the general manager of the Ship Canal Company) came to see the benefits that the industrial development of Trafford Park could offer to both the ship canal and the estate. In January 1897 Stevens became the managing director of Trafford Park Estates, where he remained until 1930, latterly as its joint chairman and managing director.

Within five years Trafford Park, Europe's largest industrial estate, was home to forty firms. The earliest structures on the canal side were grain silos; the grain was used for flour and as ballast

Sailing ballast

Ballast is used in sailboats to provide moment to resist the lateral forces on the sail. Insufficiently ballasted boats will tend to tip, or heel, excessively in high winds. Too much heel may result in the boat capsizing. If a sailing vessel should need to voyage without cargo then ballast of...

for ships carrying raw cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

. The wooden silo built opposite No.9 Dock in 1898 (destroyed in the Manchester Blitz

Manchester Blitz

The Manchester Blitz was the heavy bombing of the city of Manchester and its surrounding areas in North West England during the Second World War by the Nazi German Luftwaffe...

in 1940) was Europe's largest grain elevator. The CWS bought land on Trafford Wharf in 1903, where it opened a bacon factory and a flour mill. In 1906 it bought the Sun Mill, which it extended in 1913 to create the UK's largest flour mill, with its own wharf, elevators and silos.

Inland from the canal the British Westinghouse Electric Company

British Westinghouse

British Westinghouse Electrical and Manufacturing Company was a subsidiary of the American Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company. British Westinghouse would become a subsidiary of Metropolitan-Vickers in 1919; and after Metropolitan Vickers merged with British Thomson-Houston in 1929, it...

bought 11 per cent of the estate. Westinghouse's American architect Charles Heathcote

Charles Heathcote

Charles Heathcote was an architect who practised in Manchester. He was articled to the church architects Charles Hansom, of Clifton, Bristol...

was responsible for much of the planning and design of their factory, which built steam turbine

Steam turbine

A steam turbine is a mechanical device that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam, and converts it into rotary motion. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Parsons in 1884....

s and turbo generator

Turbo generator

A turbo generator is a turbine directly connected to an electric generator for the generation of electric power. Large steam powered turbo generators provide the majority of the world's electricity and are also used by steam powered turbo-electric ships.Smaller turbo-generators with gas turbines...

s. By 1899 Heathcote had also designed fifteen warehouses for the Manchester Ship Canal Company. Engineering companies such as Ford and Metropolitan Vickers had a large presence at Trafford Park alongside non-engineering companies such Kellogg's who remain to this day. Trafford Park was also home to the first Ford production plant for their revolutionary Model T car outside of the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

.

Trafford Park

Trafford Park is an area of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, in Greater Manchester, England. Located opposite Salford Quays, on the southern side of the Manchester Ship Canal, it is west-southwest of Manchester city centre, and north of Stretford. Until the late 19th century it was the...

, Ford of Britain

Ford of Britain

Ford of Britain is a British wholly owned subsidiary of Ford of Europe, a subsidiary of Ford Motor Company. Its business started in 1909 and has its registered office in Brentwood, Essex...

was approached about the possibility of converting it into an aircraft engine production unit by Herbert Austin

Herbert Austin

Herbert 'Pa' Austin, 1st Baron Austin KBE was an English automobile designer and builder who founded the Austin Motor Company.-Background and early life:...

, who was in charge of the shadow factory plan. Building work on a new factory was started in May 1940 on a 118 acres (47.8 ha) site, while Ford engineers went on a fact finding mission to Derby. Their chief engineer commented to Sir Stanley Hooker that the tolerances used were far too wide for them, and so the 20,000 drawings would need to be redrawn to Ford tolerance levels, which took over a year. Ford's factory was built with two distinct sections to minimise potential bomb damage, it was completed in May 1941 and bombed in the same month. At first, the factory had difficulty in attracting suitable labour, and large numbers of women, youths and untrained men had to be taken on. Despite this, the first Merlin engine came off the production line one month later and it was building the engine at a rate of 200 per week by 1943, at which point the joint factories were producing 18,000 Merlins per year. Ford’s investment in machinery and the redesign resulted in the 10,000 man-hours needed to produce a Merlin dropping to 2,727 in three years, while unit cost fell from £6,540 in June 1941 to £1,180 by the war’s end. In his autobiography Not much of an Engineer, Sir Stanley Hooker states: "... once the great Ford factory at Manchester started production, Merlins came out like shelling peas. The percentage of engines rejected by the Air Ministry was zero. Not one engine of the 30,400 produced was rejected ...". Some 17,316 people worked at the Trafford Park plant, including 7,260 women and two resident doctors and nurses. Merlin production started to run down in August 1945, and finally ceased on 23 March 1946.

The Ship Canal is now past its heyday, but still sits at Europe's largest industrial estate, Trafford Park

Trafford Park

Trafford Park is an area of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, in Greater Manchester, England. Located opposite Salford Quays, on the southern side of the Manchester Ship Canal, it is west-southwest of Manchester city centre, and north of Stretford. Until the late 19th century it was the...

and there are plans to increase shipping. Its importance highlighted by the engineering achievement that was the Manchester Ship Canal, the only ship canal

Ship canal

A ship canal is a canal especially constructed to carry ocean-going ships, as opposed to barges. Ship canals can be enlarged barge canals, canalized or channelized rivers, or canals especially constructed from the start to accommodate ships....

in Britain and growth of the first industrial estate in the world in Trafford Park

Trafford Park

Trafford Park is an area of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, in Greater Manchester, England. Located opposite Salford Quays, on the southern side of the Manchester Ship Canal, it is west-southwest of Manchester city centre, and north of Stretford. Until the late 19th century it was the...

.

The 'Nuclear Family'

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Manchester gained a pioneering reputation for a city at the centre of physics, namely in the field of nuclear physicsNuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies the building blocks and interactions of atomic nuclei. The most commonly known applications of nuclear physics are nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons technology, but the research has provided application in many fields, including those...

. The 'Nuclear Family' was the alias given to a group of scientists who studied nuclear physics in Manchester. 'Family' highlights the consistent development through the generations in nuclear physics, beginning with Thomson in the late 18th century and ending with James Chadwick

James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick CH FRS was an English Nobel laureate in physics awarded for his discovery of the neutron....

in the 1930s who discovered the neutron

Neutron

The neutron is a subatomic hadron particle which has the symbol or , no net electric charge and a mass slightly larger than that of a proton. With the exception of hydrogen, nuclei of atoms consist of protons and neutrons, which are therefore collectively referred to as nucleons. The number of...

. Ernest Rutherford is often described as the 'father of nuclear physics', equally the same could be said of J. J. Thomson who discovered the electron and isotopes, and ultimately taught Rutherford who later go on to split the atom. Scientists who were part of the 'nuclear family' in Manchester included J. J. Thomson

J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John "J. J." Thomson, OM, FRS was a British physicist and Nobel laureate. He is credited for the discovery of the electron and of isotopes, and the invention of the mass spectrometer...

, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

, Niels Bohr

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. Bohr mentored and collaborated with many of the top physicists of the century at his institute in...

, Hans Geiger, Ernest Marsden

Ernest Marsden

Sir Ernest Marsden was an English-New Zealand physicist. He was born in East Lancashire, living in Rishton and educated at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Blackburn, where an inter-house trophy rewarding academic excellence bears his name.He met Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester...

, John Cockcroft

John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft OM KCB CBE FRS was a British physicist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for splitting the atomic nucleus with Ernest Walton, and was instrumental in the development of nuclear power....

and James Chadwick

James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick CH FRS was an English Nobel laureate in physics awarded for his discovery of the neutron....

.

J. J. Thomson, a Manchester-born physicist hailing from Cheetham Hill

Cheetham Hill

Cheetham Hill is an inner city area of Manchester, England. As an electoral ward it is known as Cheetham and has a population of 12,846. It lies on the west bank of the River Irk, north-northeast of Manchester city centre and close to the boundary with the City of Salford...

, who enrolled to Owens College as a 14-year-old. Thomson would go on to discover the electron

Electron

The electron is a subatomic particle with a negative elementary electric charge. It has no known components or substructure; in other words, it is generally thought to be an elementary particle. An electron has a mass that is approximately 1/1836 that of the proton...

in 1897 and isotope

Isotope

Isotopes are variants of atoms of a particular chemical element, which have differing numbers of neutrons. Atoms of a particular element by definition must contain the same number of protons but may have a distinct number of neutrons which differs from atom to atom, without changing the designation...

, as well as inventing the mass spectrometer. All of which, contributed to his award of the Nobel Prize in Physics

Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics is awarded once a year by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895 and awarded since 1901; the others are the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Nobel Prize in Literature, Nobel Peace Prize, and...

in 1906. Thomson also proposed the plum pudding model, which was later confirmed as scientifically incorrect by Rutherford.

In 1907, Ernest Rutherford, a scientist who had been taught by Thomson at the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

, moved to Manchester to become chair of physics at the Victoria University of Manchester

Victoria University of Manchester

The Victoria University of Manchester was a university in Manchester, England. On 1 October 2004 it merged with the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology to form a new entity, "The University of Manchester".-1851 - 1951:The University was founded in 1851 as Owens College,...

. Rutherford hypothesised the Rutherford model

Rutherford model

The Rutherford model or planetary model is a model of the atom devised by Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford directed the famous Geiger-Marsden experiment in 1909, which suggested on Rutherford's 1911 analysis that the so-called "plum pudding model" of J. J. Thomson of the atom was incorrect...

, which was later improved on by Niels Bohr who proposed the Bohr model

Bohr model

In atomic physics, the Bohr model, introduced by Niels Bohr in 1913, depicts the atom as a small, positively charged nucleus surrounded by electrons that travel in circular orbits around the nucleus—similar in structure to the solar system, but with electrostatic forces providing attraction,...

. Rutherford would later have a great influence on students such as Niels Bohr

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. Bohr mentored and collaborated with many of the top physicists of the century at his institute in...

, Hans Geiger, Ernest Marsden

Ernest Marsden

Sir Ernest Marsden was an English-New Zealand physicist. He was born in East Lancashire, living in Rishton and educated at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Blackburn, where an inter-house trophy rewarding academic excellence bears his name.He met Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester...

and James Chadwick

James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick CH FRS was an English Nobel laureate in physics awarded for his discovery of the neutron....

. Rutherford's main work would come in 1917 when he would 'split the atom

Split The Atom

Split the Atom is the debut full-length album by Dutch drum and bass trio Noisia.The album was released as a full-length CD as well as two double 12" EPs; the Vision EP includes four Drum and Bass tracks whilst the Division EP includes four Electro house/Breaks tracks.Three singles have so far been...

'.

Aviation

Avro

Avro was a British aircraft manufacturer, with numerous landmark designs such as the Avro 504 trainer in the First World War, the Avro Lancaster, one of the pre-eminent bombers of the Second World War, and the delta wing Avro Vulcan, a stalwart of the Cold War.-Early history:One of the world's...

.

In 1910, French aviator Louis Paulhan

Louis Paulhan

Isidore Auguste Marie Louis Paulhan, known as Louis Paulhan, was a pioneering French aviator who in 1910 flew "Le Canard", the world's first seaplane, designed by Henri Fabre....

flew from London to Manchester in approximately 12 hours. Paulhan won the first Daily Mail aviation prizes

Daily Mail aviation prizes

Between 1907 and 1925 the Daily Mail newspaper, initially on the initiative of its proprietor Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, awarded numerous prizes for achievements in aviation. The newspaper would stipulate the amount of a prize for the first aviators to perform a particular task in...

who offered the prize in 1906.

Jack Alcock was born on 5 November 1892 at Seymour Grove, Old Trafford

Old Trafford, Manchester

Old Trafford is in Greater Manchester, England, which lies south-west of Manchester. The crossroads sites of two old toll gates roughly delineate the borders of the area: Brooks's Bar to the east and Trafford Bar to the west....

, Stretford

Stretford

Stretford is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, in Greater Manchester, England. Lying on flat ground between the River Mersey and the Manchester Ship Canal, it is to the southwest of Manchester city centre, south-southwest of Salford and northeast of Altrincham...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. He attended St Thomas's primary school in Heaton Chapel

Heaton Chapel

Heaton Chapel is an area in the northern part of Stockport, Greater Manchester, England. It borders the Manchester districts of Levenshulme to the north, the Stockport districts of Heaton Moor to the west, Reddish and Heaton Norris to the east and Heaton Mersey to the west and south...

, Stockport

Stockport

Stockport is a town in Greater Manchester, England. It lies on elevated ground southeast of Manchester city centre, at the point where the rivers Goyt and Tame join and create the River Mersey. Stockport is the largest settlement in the metropolitan borough of the same name...

. He first became interested in flying at the age of seventeen. In 1910 he became an assistant to Works Manager Charles Fletcher, an early Manchester aviator and Norman Crossland, a motor engineer and founder of Manchester Aero Club. It was during this period that Alcock met the Frenchman Maurice Ducrocq who was both a demonstration pilot and UK sales representative for aero engines made by Spirito Mario Viale in Italy.

Ducrocq took Alcock on as a mechanic at the Brooklands

Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England. It opened in 1907, and was the world's first purpose-built motorsport venue, as well as one of Britain's first airfields...

aerodrome, Surrey, where he learned to fly at Ducrocq's flying school, gaining his pilot's licence there in November 1912. By summer 1914 he was proficient enough to compete in a Hendon-Birmingham-Manchester and return air race, flying a Farman

Farman

Farman Aviation Works was an aeronautic enterprise founded and run by the brothers; Richard, Henri, and Maurice Farman. They designed and constructed aircraft and engines from 1908 until 1936; during the French nationalization and rationalization of its aerospace industry, Farman's assets were...

biplane. He landed at Trafford Park Aerodrome

Trafford Park Aerodrome (Manchester)

Trafford Park Aerodrome was the first purpose-built airfield in the Manchester area. Its large all-grass landing field was just south of the Manchester Ship Canal between Trafford Park Road, Moseley Road and Ashburton Road and occupied a large part of the former deer park of Trafford Hall...

and flew back to Hendon the same day. Alcock became an experienced military pilot and instructor during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

with the Royal Naval Air Service

Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service or RNAS was the air arm of the Royal Navy until near the end of the First World War, when it merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps to form a new service , the Royal Air Force...

, although he was shot down during a bombing raid and taken prisoner in Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

.

After the war, Alcock wanted to continue his flying career and took up the challenge of attempting to be the first to fly directly across the Atlantic. Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown

Arthur Whitten Brown

Sir Arthur Whitten Brown KBE was the navigator of the first successful non-stop transatlantic flight.-Life and work:...

took off from St John's, Newfoundland, at 1:45 pm local time on 14 June 1919, and landed in Derrygimla bog near Clifden, Ireland, 16 hours and 12 minutes later on 15 June 1919 after flying 1,980 miles (3,186 km). The flight had been much affected by bad weather, making accurate navigation difficult; the intrepid duo also had to cope with turbulence, instrument failure and ice on the wings. The flight was made in a modified Vickers Vimy

Vickers Vimy

The Vickers Vimy was a British heavy bomber aircraft of the First World War and post-First World War era. It achieved success as both a military and civil aircraft, setting several notable records in long-distance flights in the interwar period, the most celebrated of which was the first non-stop...

bomber, and won a £10,000 prize

Daily Mail aviation prizes

Between 1907 and 1925 the Daily Mail newspaper, initially on the initiative of its proprietor Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, awarded numerous prizes for achievements in aviation. The newspaper would stipulate the amount of a prize for the first aviators to perform a particular task in...

offered by London's Daily Mail

Daily Mail

The Daily Mail is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper owned by the Daily Mail and General Trust. First published in 1896 by Lord Northcliffe, it is the United Kingdom's second biggest-selling daily newspaper after The Sun. Its sister paper The Mail on Sunday was launched in 1982...

newspaper for the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic. His grave in Southern Cemetery, Manchester

Southern Cemetery, Manchester

Southern Cemetery, Manchester is a large municipal cemetery in Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Greater Manchester, England, three miles south of Manchester city centre: it was opened in 1879...

is marked by a large stone memorial alongside other famous Mancunian figures. He is buried in grave space "Church of England, Section G, Grave Number 966", alongside 4 other individuals: John Alcock, Mary Alcock, Edward Samson Alcock and Elsie Moseley.

In 1910, Eccles-born Alliott Verdon Roe

Alliott Verdon Roe

Sir Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe OBE, FRAeS was a pioneer English pilot and aircraft manufacturer, and founder in 1910 of the Avro company...

founded Avro on at Brownsfield Mill on Great Ancoats Street in Manchester city centre

Manchester City Centre

Manchester city centre is the central business district of Manchester, England. It lies within the Manchester Inner Ring Road, next to the River Irwell...

. Alongside, Farnworth

Farnworth

Farnworth is within the Metropolitan Borough of Bolton in Greater Manchester, England. It is located southeast of Bolton, 6 miles south-west of Bury , and northwest of Manchester....

-born aircraft designer Roy Chadwick

Roy Chadwick

Roy Chadwick, CBE, FRAeS was an aircraft designer for Avro. Born at Marsh Hall Farm, Farnworth in Widnes, son of the mechanical engineer Charles Chadwick, he was the Chief Designer for the Avro Company and was responsible for practically all of their aeroplane designs...

, Avro would go on to design some recognisable British aircraft of the 20th century. The Avro Lancaster bomber, devised for World War II was a redeveloped version of the Avro Manchester

Avro Manchester

|-See also:-References:NotesCitationsBibliography* Buttler, Tony. British Secret Projects: Fighters and Bombers 1935–1950. Hickley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-1857801798....

and subsequently became the most important British aircraft of the war alongside the Supermarine Spitfire

Supermarine Spitfire