Samuel Mudd

Encyclopedia

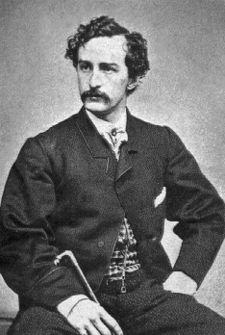

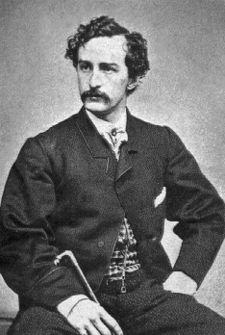

Samuel Alexander Mudd I, M.D. (December 20, 1833 – January 10, 1883) was an American

physician who was convicted and imprisoned for aiding and conspiring with John Wilkes Booth

in the 1865 assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

. He was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson

and released from prison in 1869. Despite repeated attempts by family members and others to have it expunged, his conviction has never been overturned.

, Mudd was the fourth of ten children of Henry Lowe and Sarah Ann Reeves Mudd. He grew up on "Oak Hill", his father's tobacco plantation of several hundred acres which was located 30 miles (48.3 km) southeast of downtown Washington, D.C.

, and which was worked by 89 slaves.

At the age of 15, after several years of home tutoring, Mudd went off to boarding school at St. Johns in Frederick, Maryland

. Two years later, he enrolled at Georgetown College

in Washington, D.C.. He then studied medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore

, writing his thesis on dysentery

.

Upon graduation in 1856, Mudd returned to Charles County to practice medicine, marrying his childhood sweetheart, Sarah Frances (Frankie) Dyer Mudd one year later.

As a wedding present, Mudd's father gave the couple 218 acre (0.88221548 km²) of his best farmland, known as St. Catherine’s, and a new house. While the house was under construction, the young Mudds lived with Frankie's bachelor brother, Jeremiah Dyer, finally moving into their new home in 1859. They had nine children in all; four before Mudd's arrest and five after his release from prison. To supplement his income from his medical practice, Mudd became a small scale tobacco

grower, using five slaves according to the 1860 U.S. Slave Census. Mudd believed that slavery was divinely ordained, writing a letter to the theologian Orestes Brownson

to that effect.

With the advent of the American Civil War

in 1861, the Southern Maryland

slave system and the economy it supported rapidly began to collapse. In 1863, the Union Army established Camp Stanton just 10 miles (16.1 km) from the Mudd farm to enlist black freedmen and run-away slaves. Six regiments totaling over 8,700 black soldiers, many from Southern Maryland, were trained there. In 1864, Maryland

, which was exempt from Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation

, abolished slavery, making it difficult for growers like Mudd to operate their plantations. As a result, Mudd considered selling his farm and depending on his medical practice. As Mudd pondered his alternatives, he was introduced to someone who said he might be interested in buying his property, a 26 year-old actor by the name of John Wilkes Booth.

's future assassin, John Wilkes Booth

, visited Bryantown, Maryland

, in November and December 1864, claiming to look for real estate investments. Bryantown is about 25 miles (40.2 km) from Washington, D.C., and about 5 miles (8 km) from Mudd’s farm. The real estate story was merely a cover; Booth’s true purpose was to plan an escape route as part of a plan to kidnap Lincoln. Booth believed the federal government would ransom Lincoln by releasing a large number of Confederate prisoners of war.

Historians do agree that Booth met Mudd at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Bryantown during one of those visits, probably the November visit. Booth visited Mudd at his farm the next day, and stayed there overnight. The following day, Booth purchased a horse from Mudd’s neighbor and returned to Washington. Some historians believe that Booth used his visit to Bryantown to recruit Mudd to his kidnapping plot, although others believe that Mudd would have had no interest in such a scheme.

Historians do agree that Booth met Mudd at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Bryantown during one of those visits, probably the November visit. Booth visited Mudd at his farm the next day, and stayed there overnight. The following day, Booth purchased a horse from Mudd’s neighbor and returned to Washington. Some historians believe that Booth used his visit to Bryantown to recruit Mudd to his kidnapping plot, although others believe that Mudd would have had no interest in such a scheme.

A short time later, on December 23, 1864, Mudd went to Washington where he met Booth again. Some historians believe the meeting had been arranged, while others believe it was inadvertent. The two men, plus John Surratt

, Jr. and Louis J. Weichmann

, had a conversation and drinks together, first at Booth’s hotel, and later at Mudd’s.

According to a statement made by co-conspirator George Atzerodt

, found long after his death and taken down while he was in federal custody on May 1, 1865, Mudd knew in advance about Booth's plans; Atzerodt was sure the doctor knew, he said, because Booth had "sent (as he told me) liquors & provisions [...] about two weeks before the murder to Dr. Mudd's".

After Booth shot President Lincoln on April 14, 1865, he broke his left leg while fleeing Ford's Theater. Booth met up with David Herold

and together they made for Virginia via Southern Maryland. They stopped at Mudd's house around four o'clock in the morning on April 15. Mudd set, splinted and bandaged Booth's broken leg, and arranged for a carpenter, John Best, to make a pair of crutches for Booth. "I had no proper paste-board for making splints... so..I... took a piece of bandbox and split it in half, doubled it at right angles, and took some paste and pasted it into a splint". Booth and Herold spent between twelve and fifteen hours at Mudd's house. They slept in the front bedroom on the second floor. It is unclear whether Mudd had been informed that Booth had murdered President Lincoln at that point.

Mudd went to Bryantown during the day on April 15 to run errands; if he did not already know the news of the assassination from Booth, he certainly learned of it on this trip. He returned home that evening, and accounts differ as to whether Booth and Herold had already left, whether Mudd met them as they were leaving, or whether they left at Mudd's urging and with his assistance.

Whichever is true, Mudd did not immediately contact the authorities. When questioned, he stated that he had not wanted to leave his family alone in the house lest the assassins return and find him absent and his family unprotected. He waited until Mass the following day, Easter Sunday, when he asked his second cousin, Dr. George Mudd — a resident of Bryantown — to notify the 13th New York Cavalry in Bryantown under the command of Lieutenant David Dana. This delay in contacting the authorities drew suspicion and was a significant factor in tying Mudd to the conspiracy.

During his initial investigative interview on April 18, Mudd stated that he had never seen either of the parties before. In his sworn statement of April 22, he told about Booth's visit to Bryantown in November 1864, but then said "I have never seen Booth since that time to my knowledge until last Saturday morning." He deliberately hid the fact of his meeting with Booth in Washington in December 1864. In prison, Mudd belatedly admitted the Washington meeting, saying he ran into Booth by chance during a Christmas shopping trip. Mudd’s failure to mention the meeting in his sworn statement to detectives was a big mistake. When Louis J. Weichmann

later told the authorities of this meeting, they realized Mudd had misled them, and immediately began to treat him as a suspect rather than a witness. During the conspiracy trial, Lieutenant Alexander Lovett testified that "On Friday, the 21st of April, I went to Mudd's again, for the purpose of arresting him. When he found we were going to search the house, he said something to his wife, and she went up stairs and brought down a boot. Mudd said he had cut it off the man's leg. I turned down the top of the boot, and saw the name 'J. Wilkes' written in it."

After Booth's death (April 26, 1865), Mudd was arrested and charged with conspiracy

After Booth's death (April 26, 1865), Mudd was arrested and charged with conspiracy

to murder Abraham Lincoln.

On May 1, 1865, President Andrew Johnson

ordered the formation of a nine-man military commission to try the conspirators. Mudd was represented by General Thomas Ewing, Jr.

. The trial began on May 10, 1865. Mary Surratt

, Lewis Powell

, George Atzerodt

, David Herold

, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlen

, Edmund Spangler

and Samuel Arnold

were all charged with conspiring to murder Lincoln. The prosecution called 366 witnesses.

The defense sought to prove that Mudd was a loyal citizen, citing his self-description as a "Union man" and asserting that he was "a deeply religious man, devoted to family, and a kind master to his slaves". The prosecution presented witnesses who testified that he had shot one of his slaves in the leg, and threatened to send others to Richmond, Virginia

to assist in the construction of Confederate defenses. The prosecution also contended that he had been a member of a Confederate communications distribution agency and had sheltered Confederate soldiers on his plantation.

On June 29, 1865, Mudd was found guilty with the others. The testimony of Louis J. Weichmann

was crucial in obtaining the convictions. According to the historian Edward Steers, the testimony presented by former slaves was also crucial, although it faded from public memory. Mudd escaped the death penalty by one vote and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Four of the defendants, Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold, were hanged

at the Old Penitentiary at the Washington Arsenal on July 7, 1865.

in the Dry Tortugas

about 70 miles (112.7 km) west of Key West

, Florida. The fort housed Union Army deserters and held about six hundred prisoners when Mudd and the others arrived. Prisoners lived on the second tier of the fort, in unfinished open-air gun rooms called casemates. Mudd and his three companions lived in the casemate directly above the fort's main entrance, called the Sally Port.

In September 1865, two months after Mudd arrived, control of Fort Jefferson was transferred from the 161st New York Volunteers to the 82nd United States Colored Infantry. On September 25, 1865, he attempted to escape from Fort Jefferson by stowing away on the transport Thomas A. Scott. Some historians believe that as a recent slave owner and a person convicted of conspiring to kill the president whose presidency led to the freeing of the slaves, Mudd was fearful of his treatment by the incoming 82nd United States Colored Infantry and this is why he made his bid for freedom.

In September 1865, two months after Mudd arrived, control of Fort Jefferson was transferred from the 161st New York Volunteers to the 82nd United States Colored Infantry. On September 25, 1865, he attempted to escape from Fort Jefferson by stowing away on the transport Thomas A. Scott. Some historians believe that as a recent slave owner and a person convicted of conspiring to kill the president whose presidency led to the freeing of the slaves, Mudd was fearful of his treatment by the incoming 82nd United States Colored Infantry and this is why he made his bid for freedom.

He was quickly discovered and placed in the fort's guardhouse. On October 18, he was transferred along with Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlen, Edman Spangler, and George St. Leger Grenfell

to a large empty ground-level gunroom the soldiers referred to as "the dungeon". Mudd and the others were let out of the dungeon six days a week to work around the fort. On Sundays and holidays they were confined inside. The men wore leg irons while working outside, but the irons were removed when inside the dungeon.

After three months in the dungeon, Mudd and the others were returned to the general prison population. However, because of his attempted escape, Mudd lost his privilege of working in the prison hospital and was assigned to work in the prison carpentry shop with Spangler.

There was an outbreak of yellow fever

in the fall of 1867 at the fort. Michael O'Laughlen

eventually died of it on September 23. The prison doctor died and Mudd agreed to take over the position. In this role he was able to help stem the spread of the disease. The soldiers in the fort wrote a petition to President Johnson in October 1867 stating of Mudd's assistance, "He inspired the hopeless with courage and by his constant presence in the midst of danger and infection.... [Many] doubtless owe their lives to the care and treatment they received at his hands." Probably as a reward for his work in the yellow fever epidemic, Dr. Mudd was reassigned from the carpentry shop to a clerical job in the Provost Marshall's office, where he remained until his pardon.

ed by President Andrew Johnson. He was released from prison on March 8, 1869 and returned home to Maryland on March 20, 1869. On March 1, 1869, three weeks after he pardoned Mudd, Johnson also pardoned Spangler and Arnold.

When Mudd returned home, well-wishing friends and strangers, as well as inquiring newspaper reporters, besieged him. Mudd was very reluctant to talk to the press because he felt they had misquoted him in the past. He gave one interview after his release to the New York Herald

, but immediately regretted it, complaining that the article had several factual errors and that it misrepresented his work during the yellow fever epidemic. On the whole though, Mudd continued to enjoy the friendship of his friends and neighbors. He resumed his medical practice and slowly brought the family farm back to productivity.

In 1873, Spangler traveled to the Mudd farm, where Mudd and his wife welcomed him as the friend whom Mudd credited with saving his life while suffering with yellow fever at Fort Jefferson. Spangler lived with the Mudd family for about eighteen months, earning his keep by doing carpentry, gardening, and other farm chores, until his death on February 7, 1875.

Mudd always had an interest in politics. While in prison, he stayed abreast of political happenings through the newspapers he was sent. After his release, he became active again in community affairs. In 1874, he was elected chief officer of the local farmers association, the Bryantown Grange. In 1876, he was elected Vice President of the local Democratic Tilden

-Hendricks

presidential election committee. Tilden lost that year to Republican

Rutherford B. Hayes

in a hotly disputed election. The next year Mudd ran as a Democratic candidate for the Maryland House of Delegates

, but was defeated by the popular Republican William Mitchell.

Mudd’s ninth child, Mary Eleanor “Nettie” Mudd, was born in 1878. That same year, he and his wife temporarily took in a seven-year-old orphan named John Burke, one of 300 abandoned children sent to Maryland families from the New York City Foundling Asylum run by the Catholic Sisters of Charity

. The Burke boy was permanently settled with farmer Ben Jenkins.

In 1880, the Port Tobacco Times reported that Mudd’s barn containing almost eight thousand pounds of tobacco, two horses, a wagon, and farm implements was destroyed by fire.

Mudd was just 49 years old when he died of pneumonia

on January 10, 1883. He is buried in the cemetery at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Bryantown, the same church where he once met up with John Wilkes Booth.

Richard Mudd petitioned several successive Presidents, receiving replies from Presidents Jimmy Carter

and Ronald Reagan

. Carter, while sympathetic, responded that he had no authority under law to set aside the conviction; Reagan that he had come to believe that Samuel Mudd was innocent of any wrongdoing. In 1992 Representatives Steny Hoyer

and Thomas W. Ewing

introduced House Bill 1885 to overturn the conviction, but it failed while in committee. Mudd then turned to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records, which recommended that the conviction be overturned on the basis that Mudd should have been tried by a civilian court. The recommendation was rejected by Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army William D. Clark

. Several other legal venues were attempted, ending in 2003 when the U.S. Supreme Court refused the case, stating that the deadline for filing had been missed.

St. Catharine

, also known as the Dr. Samuel A. Mudd House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

in 1974.

-directed film The Prisoner of Shark Island

, based on a script by Nunnally Johnson

. Another film, entitled The Ordeal of Dr. Mudd, was made in 1980. It starred Dennis Weaver

as Mudd, and espoused the point of view that Mudd was innocent of any conspiracy.

Roger Mudd

, an Emmy Award

-winning journalist and television host, is related to Samuel Mudd, though he is not a direct descendant, as has been mistakenly reported.

On the episode Swiss Diplomacy

of the NBC Drama The West Wing, first lady (and cardiac surgeon) Dr. Abby Bartlet commented on the duty of a physician to treat an injured patient despite potential legal repercussions. She responded to Mudd's treason conviction with "So that's the way it goes. You set the leg".

Samuel Mudd is sometimes given as the origin of the phrase "your name is mud", as in, for example, the 2007 film National Treasure: Book of Secrets. However, according to an online etymology dictionary, this phrase has its earliest known recorded instance in 1823, ten years before Mudd's birth, and is based on an obsolete sense of the word "mud" meaning "a stupid twaddling fellow".

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

physician who was convicted and imprisoned for aiding and conspiring with John Wilkes Booth

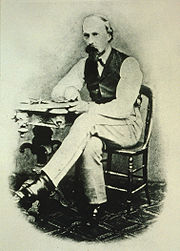

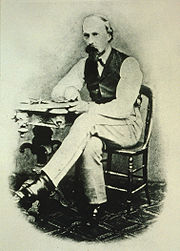

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth was an American stage actor who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. Booth was a member of the prominent 19th century Booth theatrical family from Maryland and, by the 1860s, was a well-known actor...

in the 1865 assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

. He was pardoned by President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

and released from prison in 1869. Despite repeated attempts by family members and others to have it expunged, his conviction has never been overturned.

Early years

Born in Charles County, MarylandCharles County, Maryland

Charles County is a county in the south central portion of the U.S. state of Maryland.As of 2010, the population was 146,551. Its county seat is La Plata. This county was named for Charles Calvert , third Baron Baltimore....

, Mudd was the fourth of ten children of Henry Lowe and Sarah Ann Reeves Mudd. He grew up on "Oak Hill", his father's tobacco plantation of several hundred acres which was located 30 miles (48.3 km) southeast of downtown Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, and which was worked by 89 slaves.

At the age of 15, after several years of home tutoring, Mudd went off to boarding school at St. Johns in Frederick, Maryland

Frederick, Maryland

Frederick is a city in north-central Maryland. It is the county seat of Frederick County, the largest county by area in the state of Maryland. Frederick is an outlying community of the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is part of a greater...

. Two years later, he enrolled at Georgetown College

Georgetown College (Georgetown University)

Georgetown College, infrequently Georgetown College of Arts and Sciences, is the oldest school within Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. The College is the largest undergraduate school at Georgetown, and until the founding of the Medical School in 1850, was the only higher education division...

in Washington, D.C.. He then studied medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore

University of Maryland, Baltimore

University of Maryland, Baltimore, was founded in 1807. It comprises some of the oldest professional schools in the nation and world. It is the original campus of the University System of Maryland. Located on 60 acres in downtown Baltimore, Maryland, it is part of the University System of Maryland...

, writing his thesis on dysentery

Dysentery

Dysentery is an inflammatory disorder of the intestine, especially of the colon, that results in severe diarrhea containing mucus and/or blood in the faeces with fever and abdominal pain. If left untreated, dysentery can be fatal.There are differences between dysentery and normal bloody diarrhoea...

.

Upon graduation in 1856, Mudd returned to Charles County to practice medicine, marrying his childhood sweetheart, Sarah Frances (Frankie) Dyer Mudd one year later.

As a wedding present, Mudd's father gave the couple 218 acre (0.88221548 km²) of his best farmland, known as St. Catherine’s, and a new house. While the house was under construction, the young Mudds lived with Frankie's bachelor brother, Jeremiah Dyer, finally moving into their new home in 1859. They had nine children in all; four before Mudd's arrest and five after his release from prison. To supplement his income from his medical practice, Mudd became a small scale tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

grower, using five slaves according to the 1860 U.S. Slave Census. Mudd believed that slavery was divinely ordained, writing a letter to the theologian Orestes Brownson

Orestes Brownson

Orestes Augustus Brownson was a New England intellectual and activist, preacher, labor organizer, and noted Catholic convert and writer...

to that effect.

With the advent of the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

in 1861, the Southern Maryland

Southern Maryland

Southern Maryland in popular usage is composed of the state's southernmost counties on the "Western Shore" of the Chesapeake Bay. This region includes all of Calvert, Charles and St. Mary's counties and sometimes the southern portions of Anne Arundel and Prince George's counties.- History...

slave system and the economy it supported rapidly began to collapse. In 1863, the Union Army established Camp Stanton just 10 miles (16.1 km) from the Mudd farm to enlist black freedmen and run-away slaves. Six regiments totaling over 8,700 black soldiers, many from Southern Maryland, were trained there. In 1864, Maryland

Maryland

Maryland is a U.S. state located in the Mid Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware to its east...

, which was exempt from Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation

Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

, abolished slavery, making it difficult for growers like Mudd to operate their plantations. As a result, Mudd considered selling his farm and depending on his medical practice. As Mudd pondered his alternatives, he was introduced to someone who said he might be interested in buying his property, a 26 year-old actor by the name of John Wilkes Booth.

Booth connection

Many historians agree that President Abraham LincolnAbraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

's future assassin, John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth was an American stage actor who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. Booth was a member of the prominent 19th century Booth theatrical family from Maryland and, by the 1860s, was a well-known actor...

, visited Bryantown, Maryland

Bryantown, Maryland

Bryantown is an unincorporated community in Charles County, Maryland, United States, adjacent to Maryland Route 5. Bryantown stands on land known as Boarman's Manor, a manor granted to Major William Boarman in 1674....

, in November and December 1864, claiming to look for real estate investments. Bryantown is about 25 miles (40.2 km) from Washington, D.C., and about 5 miles (8 km) from Mudd’s farm. The real estate story was merely a cover; Booth’s true purpose was to plan an escape route as part of a plan to kidnap Lincoln. Booth believed the federal government would ransom Lincoln by releasing a large number of Confederate prisoners of war.

A short time later, on December 23, 1864, Mudd went to Washington where he met Booth again. Some historians believe the meeting had been arranged, while others believe it was inadvertent. The two men, plus John Surratt

John Surratt

John Harrison Surratt, Jr. was accused of plotting with John Wilkes Booth to kidnap U.S. president Abraham Lincoln and suspected of involvement in the Abraham Lincoln assassination. His mother Mary Surratt was convicted of conspiracy and hanged by the United States Federal Government...

, Jr. and Louis J. Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann was one of the chief witnesses for the prosecution in the conspiracy trial of the Abraham Lincoln assassination. Previously, he had been also a suspect because of his association with Mary Surratt's family.-Background and early life:Weichmann was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the...

, had a conversation and drinks together, first at Booth’s hotel, and later at Mudd’s.

According to a statement made by co-conspirator George Atzerodt

George Atzerodt

George Andreas Atzerodt was a conspirator, with John Wilkes Booth, in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Assigned to assassinate Vice-President Andrew Johnson, he lost his nerve and did not make an attempt. He was executed along with three other conspirators by hanging.-Early life:Atzerodt...

, found long after his death and taken down while he was in federal custody on May 1, 1865, Mudd knew in advance about Booth's plans; Atzerodt was sure the doctor knew, he said, because Booth had "sent (as he told me) liquors & provisions [...] about two weeks before the murder to Dr. Mudd's".

After Booth shot President Lincoln on April 14, 1865, he broke his left leg while fleeing Ford's Theater. Booth met up with David Herold

David Herold

David Edgar Herold was an accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. After guiding fellow conspirator Lewis Powell to the home of Secretary of State William H. Seward, whom Powell intended to kill, Herold fled and rendezvoused outside of Washington, D.C., with Booth...

and together they made for Virginia via Southern Maryland. They stopped at Mudd's house around four o'clock in the morning on April 15. Mudd set, splinted and bandaged Booth's broken leg, and arranged for a carpenter, John Best, to make a pair of crutches for Booth. "I had no proper paste-board for making splints... so..I... took a piece of bandbox and split it in half, doubled it at right angles, and took some paste and pasted it into a splint". Booth and Herold spent between twelve and fifteen hours at Mudd's house. They slept in the front bedroom on the second floor. It is unclear whether Mudd had been informed that Booth had murdered President Lincoln at that point.

Mudd went to Bryantown during the day on April 15 to run errands; if he did not already know the news of the assassination from Booth, he certainly learned of it on this trip. He returned home that evening, and accounts differ as to whether Booth and Herold had already left, whether Mudd met them as they were leaving, or whether they left at Mudd's urging and with his assistance.

Whichever is true, Mudd did not immediately contact the authorities. When questioned, he stated that he had not wanted to leave his family alone in the house lest the assassins return and find him absent and his family unprotected. He waited until Mass the following day, Easter Sunday, when he asked his second cousin, Dr. George Mudd — a resident of Bryantown — to notify the 13th New York Cavalry in Bryantown under the command of Lieutenant David Dana. This delay in contacting the authorities drew suspicion and was a significant factor in tying Mudd to the conspiracy.

During his initial investigative interview on April 18, Mudd stated that he had never seen either of the parties before. In his sworn statement of April 22, he told about Booth's visit to Bryantown in November 1864, but then said "I have never seen Booth since that time to my knowledge until last Saturday morning." He deliberately hid the fact of his meeting with Booth in Washington in December 1864. In prison, Mudd belatedly admitted the Washington meeting, saying he ran into Booth by chance during a Christmas shopping trip. Mudd’s failure to mention the meeting in his sworn statement to detectives was a big mistake. When Louis J. Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann was one of the chief witnesses for the prosecution in the conspiracy trial of the Abraham Lincoln assassination. Previously, he had been also a suspect because of his association with Mary Surratt's family.-Background and early life:Weichmann was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the...

later told the authorities of this meeting, they realized Mudd had misled them, and immediately began to treat him as a suspect rather than a witness. During the conspiracy trial, Lieutenant Alexander Lovett testified that "On Friday, the 21st of April, I went to Mudd's again, for the purpose of arresting him. When he found we were going to search the house, he said something to his wife, and she went up stairs and brought down a boot. Mudd said he had cut it off the man's leg. I turned down the top of the boot, and saw the name 'J. Wilkes' written in it."

Trial

Conspiracy (crime)

In the criminal law, a conspiracy is an agreement between two or more persons to break the law at some time in the future, and, in some cases, with at least one overt act in furtherance of that agreement...

to murder Abraham Lincoln.

On May 1, 1865, President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

ordered the formation of a nine-man military commission to try the conspirators. Mudd was represented by General Thomas Ewing, Jr.

Thomas Ewing, Jr.

Thomas Ewing, Jr. was an attorney, the first chief justice of Kansas and leading free state advocate, Union Army general during the American Civil War, and two-term United States Congressman from Ohio, 1877-1881. He narrowly lost the 1880 campaign for Ohio Governor.-Early life and career:Ewing...

. The trial began on May 10, 1865. Mary Surratt

Mary Surratt

Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt was an American boarding house owner who was convicted of taking part in the conspiracy to assassinate Abraham Lincoln. Sentenced to death, she was hanged, becoming the first woman executed by the United States federal government. She was the mother of John H...

, Lewis Powell

Lewis Powell (assassin)

Lewis Thornton Powell , also known as Lewis Paine or Payne, attempted unsuccessfully to assassinate United States Secretary of State William H...

, George Atzerodt

George Atzerodt

George Andreas Atzerodt was a conspirator, with John Wilkes Booth, in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Assigned to assassinate Vice-President Andrew Johnson, he lost his nerve and did not make an attempt. He was executed along with three other conspirators by hanging.-Early life:Atzerodt...

, David Herold

David Herold

David Edgar Herold was an accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. After guiding fellow conspirator Lewis Powell to the home of Secretary of State William H. Seward, whom Powell intended to kill, Herold fled and rendezvoused outside of Washington, D.C., with Booth...

, Samuel Mudd, Michael O'Laughlen

Michael O'Laughlen

Michael O'Laughlen, Jr. was a conspirator in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln...

, Edmund Spangler

Edmund Spangler

Edmund Spangler , also known as Edman, Edward, and Ned Spangler, was originally from York, Pennsylvania, but he spent the majority of his life in the Baltimore, Maryland area...

and Samuel Arnold

Samuel Arnold (Lincoln conspirator)

Samuel Bland Arnold was involved in the plot to kidnap President Abraham Lincoln in 1865.He and the other conspirators, John Wilkes Booth, David Herold, Lewis Powell, Michael O'Laughlen and John Surratt, were to kidnap Lincoln and hold him to exchange for the Confederate prisoners in Washington D.C....

were all charged with conspiring to murder Lincoln. The prosecution called 366 witnesses.

The defense sought to prove that Mudd was a loyal citizen, citing his self-description as a "Union man" and asserting that he was "a deeply religious man, devoted to family, and a kind master to his slaves". The prosecution presented witnesses who testified that he had shot one of his slaves in the leg, and threatened to send others to Richmond, Virginia

Richmond, Virginia

Richmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

to assist in the construction of Confederate defenses. The prosecution also contended that he had been a member of a Confederate communications distribution agency and had sheltered Confederate soldiers on his plantation.

On June 29, 1865, Mudd was found guilty with the others. The testimony of Louis J. Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann

Louis J. Weichmann was one of the chief witnesses for the prosecution in the conspiracy trial of the Abraham Lincoln assassination. Previously, he had been also a suspect because of his association with Mary Surratt's family.-Background and early life:Weichmann was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the...

was crucial in obtaining the convictions. According to the historian Edward Steers, the testimony presented by former slaves was also crucial, although it faded from public memory. Mudd escaped the death penalty by one vote and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Four of the defendants, Surratt, Powell, Atzerodt and Herold, were hanged

Hanging

Hanging is the lethal suspension of a person by a ligature. The Oxford English Dictionary states that hanging in this sense is "specifically to put to death by suspension by the neck", though it formerly also referred to crucifixion and death by impalement in which the body would remain...

at the Old Penitentiary at the Washington Arsenal on July 7, 1865.

Imprisonment

Mudd, O'Laughlen, Arnold and Spangler were imprisoned at Fort JeffersonDry Tortugas National Park

Dry Tortugas National Park preserves Fort Jefferson and the Dry Tortugas section of the Florida Keys. The park covers 101 mi2 , mostly water, about 68 statute miles west of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico....

in the Dry Tortugas

Dry Tortugas

The Dry Tortugas are a small group of islands, located at the end of the Florida Keys, USA, about west of Key West, and west of the Marquesas Keys, the closest islands. Still further west is the Tortugas Bank, which is completely submerged. The first Europeans to discover the islands were the...

about 70 miles (112.7 km) west of Key West

Key West

Key West is an island in the Straits of Florida on the North American continent at the southernmost tip of the Florida Keys. Key West is home to the southernmost point in the Continental United States; the island is about from Cuba....

, Florida. The fort housed Union Army deserters and held about six hundred prisoners when Mudd and the others arrived. Prisoners lived on the second tier of the fort, in unfinished open-air gun rooms called casemates. Mudd and his three companions lived in the casemate directly above the fort's main entrance, called the Sally Port.

He was quickly discovered and placed in the fort's guardhouse. On October 18, he was transferred along with Samuel Arnold, Michael O’Laughlen, Edman Spangler, and George St. Leger Grenfell

George St. Leger Grenfell

George St. Leger Grenfell was a British soldier of fortune, of the Cornish family, who claimed to have fought in Algeria, in Morocco against the Barbary pirates, under Garibaldi in South America, in the Crimean War, and in the Sepoy Mutiny...

to a large empty ground-level gunroom the soldiers referred to as "the dungeon". Mudd and the others were let out of the dungeon six days a week to work around the fort. On Sundays and holidays they were confined inside. The men wore leg irons while working outside, but the irons were removed when inside the dungeon.

After three months in the dungeon, Mudd and the others were returned to the general prison population. However, because of his attempted escape, Mudd lost his privilege of working in the prison hospital and was assigned to work in the prison carpentry shop with Spangler.

There was an outbreak of yellow fever

Yellow fever

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family....

in the fall of 1867 at the fort. Michael O'Laughlen

Michael O'Laughlen

Michael O'Laughlen, Jr. was a conspirator in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln...

eventually died of it on September 23. The prison doctor died and Mudd agreed to take over the position. In this role he was able to help stem the spread of the disease. The soldiers in the fort wrote a petition to President Johnson in October 1867 stating of Mudd's assistance, "He inspired the hopeless with courage and by his constant presence in the midst of danger and infection.... [Many] doubtless owe their lives to the care and treatment they received at his hands." Probably as a reward for his work in the yellow fever epidemic, Dr. Mudd was reassigned from the carpentry shop to a clerical job in the Provost Marshall's office, where he remained until his pardon.

Career after release

Due in part to the influence of his defense attorney, Thomas Ewing Jr., who was influential in the President's administration, on February 8, 1869, Mudd was pardonPardon

Clemency means the forgiveness of a crime or the cancellation of the penalty associated with it. It is a general concept that encompasses several related procedures: pardoning, commutation, remission and reprieves...

ed by President Andrew Johnson. He was released from prison on March 8, 1869 and returned home to Maryland on March 20, 1869. On March 1, 1869, three weeks after he pardoned Mudd, Johnson also pardoned Spangler and Arnold.

When Mudd returned home, well-wishing friends and strangers, as well as inquiring newspaper reporters, besieged him. Mudd was very reluctant to talk to the press because he felt they had misquoted him in the past. He gave one interview after his release to the New York Herald

New York Herald

The New York Herald was a large distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between May 6, 1835, and 1924.-History:The first issue of the paper was published by James Gordon Bennett, Sr., on May 6, 1835. By 1845 it was the most popular and profitable daily newspaper in the UnitedStates...

, but immediately regretted it, complaining that the article had several factual errors and that it misrepresented his work during the yellow fever epidemic. On the whole though, Mudd continued to enjoy the friendship of his friends and neighbors. He resumed his medical practice and slowly brought the family farm back to productivity.

In 1873, Spangler traveled to the Mudd farm, where Mudd and his wife welcomed him as the friend whom Mudd credited with saving his life while suffering with yellow fever at Fort Jefferson. Spangler lived with the Mudd family for about eighteen months, earning his keep by doing carpentry, gardening, and other farm chores, until his death on February 7, 1875.

Mudd always had an interest in politics. While in prison, he stayed abreast of political happenings through the newspapers he was sent. After his release, he became active again in community affairs. In 1874, he was elected chief officer of the local farmers association, the Bryantown Grange. In 1876, he was elected Vice President of the local Democratic Tilden

Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden was the Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency in the disputed election of 1876, one of the most controversial American elections of the 19th century. He was the 25th Governor of New York...

-Hendricks

Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks was an American politician who served as a Representative and a Senator from Indiana, the 16th Governor of Indiana , and the 21st Vice President of the United States...

presidential election committee. Tilden lost that year to Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

in a hotly disputed election. The next year Mudd ran as a Democratic candidate for the Maryland House of Delegates

Maryland House of Delegates

The Maryland House of Delegates is the lower house of the General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland, and is composed of 141 Delegates elected from 47 districts. The House chamber is located in the state capitol building on State Circle in Annapolis...

, but was defeated by the popular Republican William Mitchell.

Mudd’s ninth child, Mary Eleanor “Nettie” Mudd, was born in 1878. That same year, he and his wife temporarily took in a seven-year-old orphan named John Burke, one of 300 abandoned children sent to Maryland families from the New York City Foundling Asylum run by the Catholic Sisters of Charity

Sisters of Charity of New York

The Sisters of Charity of New York is a religious congregation of women in the Catholic Church whose primary missions are education and nursing and who are dedicated in particular to the service of the poor.-History:...

. The Burke boy was permanently settled with farmer Ben Jenkins.

In 1880, the Port Tobacco Times reported that Mudd’s barn containing almost eight thousand pounds of tobacco, two horses, a wagon, and farm implements was destroyed by fire.

Mudd was just 49 years old when he died of pneumonia

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung—especially affecting the microscopic air sacs —associated with fever, chest symptoms, and a lack of air space on a chest X-ray. Pneumonia is typically caused by an infection but there are a number of other causes...

on January 10, 1883. He is buried in the cemetery at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Bryantown, the same church where he once met up with John Wilkes Booth.

Posthumous rehabilitation attempts

Mudd's grandson, Dr. Richard Mudd, tried unsuccessfully to clear his grandfather's name from the stigma of aiding John Wilkes Booth. In 1951, he published The Mudd Family of the United States, an encyclopedic two-volume history of the Mudd family in America, beginning with Thomas Mudd who arrived from England in 1665. A second edition was published in 1969.Richard Mudd petitioned several successive Presidents, receiving replies from Presidents Jimmy Carter

Jimmy Carter

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office...

and Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

. Carter, while sympathetic, responded that he had no authority under law to set aside the conviction; Reagan that he had come to believe that Samuel Mudd was innocent of any wrongdoing. In 1992 Representatives Steny Hoyer

Steny Hoyer

Steny Hamilton Hoyer is the U.S. Representative for , serving since 1981. The district includes a large swath of rural and suburban territory southeast of Washington, D.C.. He is a member of the Democratic Party....

and Thomas W. Ewing

Thomas W. Ewing

Thomas W. "Tom" Ewing is a former Republican member of the United States House of Representatives and the Illinois State House of Representatives. Ewing was a state representative from 1974 to 1991, and a U.S. Congressman representing the 15th district of Illinois from July 2, 1991 until his...

introduced House Bill 1885 to overturn the conviction, but it failed while in committee. Mudd then turned to the Army Board for Correction of Military Records, which recommended that the conviction be overturned on the basis that Mudd should have been tried by a civilian court. The recommendation was rejected by Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army William D. Clark

William D. Clark

William D. Clark was an economist and the first director of the Overseas Development Institute.-Links:* at the World Bank...

. Several other legal venues were attempted, ending in 2003 when the U.S. Supreme Court refused the case, stating that the deadline for filing had been missed.

St. Catharine

St. Catharine (Waldorf, Maryland)

St. Catharine, also known as Dr. Samuel A. Mudd House, is a historic house near Waldorf, Maryland. It is a two part frame farmhouse with a two-story, three-bay side-passage main house with a a smaller two-story, two-bay wing. It features a one-story hip-roofed porch across the facade added in 1928....

, also known as the Dr. Samuel A. Mudd House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places is the United States government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects deemed worthy of preservation...

in 1974.

Film and television

Mudd's life was the subject of a 1936 John FordJohn Ford

John Ford was an American film director. He was famous for both his westerns such as Stagecoach, The Searchers, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and adaptations of such classic 20th-century American novels as The Grapes of Wrath...

-directed film The Prisoner of Shark Island

The Prisoner of Shark Island

The Prisoner of Shark Island is a 1936 film loosely based on the life of Samuel Mudd, produced by Darryl F. Zanuck, directed by John Ford, and starring Warner Baxter and Gloria Stuart.-Plot:...

, based on a script by Nunnally Johnson

Nunnally Johnson

Nunnally Hunter Johnson was an American filmmaker who wrote, produced, and directed motion pictures.Johnson was born in Columbus, Georgia. He began his career as a journalist, writing for the Columbus Enquirer Sun, the Savannah Press, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and the New York Herald Tribune...

. Another film, entitled The Ordeal of Dr. Mudd, was made in 1980. It starred Dennis Weaver

Dennis Weaver

William Dennis Weaver was an American actor, best known for his work in television, including roles on Gunsmoke, as Marshal Sam McCloud on the NBC police drama McCloud, and the 1971 TV movie Duel....

as Mudd, and espoused the point of view that Mudd was innocent of any conspiracy.

Roger Mudd

Roger Mudd

Roger Mudd is a U.S. television journalist and broadcaster, most recently as the primary anchor for The History Channel. Previously, Mudd was weekend and weekday substitute anchor of CBS Evening News, co-anchor of the weekday NBC Nightly News, and hosted NBC's Meet the Press, and NBC's American...

, an Emmy Award

Emmy Award

An Emmy Award, often referred to simply as the Emmy, is a television production award, similar in nature to the Peabody Awards but more focused on entertainment, and is considered the television equivalent to the Academy Awards and the Grammy Awards .A majority of Emmys are presented in various...

-winning journalist and television host, is related to Samuel Mudd, though he is not a direct descendant, as has been mistakenly reported.

On the episode Swiss Diplomacy

Swiss Diplomacy

"Swiss Diplomacy" is episode 74 of The West Wing. It is the second episode not written by Aaron Sorkin, and the first since Season One's Enemies.-Plot:...

of the NBC Drama The West Wing, first lady (and cardiac surgeon) Dr. Abby Bartlet commented on the duty of a physician to treat an injured patient despite potential legal repercussions. She responded to Mudd's treason conviction with "So that's the way it goes. You set the leg".

Samuel Mudd is sometimes given as the origin of the phrase "your name is mud", as in, for example, the 2007 film National Treasure: Book of Secrets. However, according to an online etymology dictionary, this phrase has its earliest known recorded instance in 1823, ten years before Mudd's birth, and is based on an obsolete sense of the word "mud" meaning "a stupid twaddling fellow".