Rowland Hill (postal reformer)

Encyclopedia

Sir Rowland Hill KCB

, FRS (3 December 1795 - 27 August 1879) was an English

teacher

, inventor and social reformer

. He campaigned for a comprehensive reform of the postal system, based on the concept of penny postage and his solution of prepayment, facilitating the safe, speedy and cheap transfer of letters. Hill later served as a government postal official, and he is usually credited with originating the basic concepts of the modern postal service, including the invention of the postage stamp

.

, Worcestershire

, England

. Rowland's father, Thomas Wright Hill

, was an innovator in education and politics, including among his friends Joseph Priestley

, Tom Paine and Richard Price

. At the age of eleven, Rowland became a student-teacher in his father's school. He taught astronomy and earned extra money fixing scientific instruments. He also worked at the Assay Office

in Birmingham and painted landscapes in his spare time.

, an affluent neighbourhood of Birmingham

, as an “educational refraction of Priestley's ideas”. Hazelwood was to provide a model for public education

for the emerging middle classes, aiming for useful, pupil-centred education which would give sufficient knowledge, skills and understanding to allow a student to continue self-education through a life “most useful to society and most happy to himself”. The school, which Hill designed, included such marvels (for its time) as a science lab, a swimming pool, and forced air heating. In his Plans for the Government and Liberal Instruction of Boys in Large Numbers Drawn from Experience (1822, often cited as Public Education) he argued that kindness, instead of caning, and moral influence, rather than fear, should be the predominant forces in school discipline. Science was to be a compulsory subject, and students were to be self-governing.

Hazelwood gained international attention when French education leader and editor Marc Antoine Jullien

, former secretary to Robespierre, visited and wrote about the school in the June 1823 issue of his journal Revue encyclopédique. Jullien even transferred his son there. Hazelwood so impressed Jeremy Bentham

that in 1827 a branch of the school was created at Bruce Castle

in Tottenham

, London. In 1833, the original Hazelwood School closed and its educational system was continued at the new Bruce Castle School

of which Hill was head master from 1827 until 1839.

was a project of Edward Gibbon Wakefield

, who believed that many of the social problems in Britain were caused by overcrowding and overpopulation. In 1832 Rowland Hill published a tract, entitled

Home colonies : sketch of a plan for the gradual extinction of pauperism, and for the diminution of crime, based on a Dutch model. Hill then served from 1833 until 1839 as secretary of the South Australian Colonization Commission, which worked successfully to establish a settlement without convicts at what is today Adelaide

. The political economist, Robert Torrens

was chairman of the Commission. Under the South Australia Act 1834

, the colony was to embody the ideals and best qualities of British society, shaped by religious freedom and a commitment to social progress

and civil liberties

.

, on 4 January 1837. This first edition was marked “private and confidential” and was not released to the general public. The Chancellor summoned Hill to a meeting during which the Chancellor suggested improvements, asked for reconsiderations and requested a supplement which Hill duly produced and supplied on 28 January 1837.

In the 1830s at least 12½% of all British mail was conveyed under the personal frank of peers, dignitaries and Members of Parliament, while censorship and political espionage were conducted by postal officials. Fundamentally, the postal system was mismanaged, wasteful, expensive and slow. It had become inadequate for the needs of an expanding commercial and industrial nation. There is a well-known story, probably apocryphal, about how Hill gained an interest in reforming the postal system; he apparently noticed a young woman too poor to redeem a letter sent to her by her fiancé. At that time, letters were normally paid for by the recipient, not the sender. The recipient could simply refuse delivery. Frauds were commonplace; for example, coded information could appear on the cover of the letter; the recipient would examine the cover to gain the information, and then refuse delivery to avoid payment. Each individual letter had to be logged. In addition, postal rates were complex, depending on the distance and the number of sheets in the letter.

Richard Cobden

and John Ramsey McCulloch, both advocates of free trade, attacked the policies of privilege and protection of the Tory government. McCulloch, in 1833, advanced the view that "nothing contributes more to facilitate commerce than the safe, speedy and cheap conveyance of letters."

Hill's famous pamphlet, Post Office Reform: its Importance and Practicability, referred to above, was privately circulated in 1837. The report called for "low and uniform rates" according to weight, rather than distance. Hill's study showed that most of the costs in the postal system were not for transport, but rather for laborious handling procedures at the origins and the destinations. Costs could be reduced dramatically if postage were prepaid by the sender, the prepayment to be proven by the use of prepaid letter sheets or adhesive stamps (adhesive stamps had long been used to show payment of taxes, on documents for example). Letter sheet

s were to be used because envelopes were not yet common; they were not yet mass-produced, and in an era when postage was calculated partly on the basis of the number of sheets of paper used, the same sheet of paper would be folded and serve for both the message and the address. In addition, Hill proposed to lower the postage rate to a penny per half ounce, without regard to distance. He first presented his proposal to the Government in 1837.

In the House of Lords the Postmaster, Lord Lichfield

In the House of Lords the Postmaster, Lord Lichfield

, thundered about Hill's "wild and visionary schemes." William Leader Maberly

, Secretary to the Post Office, denounced Hill's study: "This plan appears to be a preposterous one, utterly unsupported by facts and resting entirely on assumption". But merchants, traders and bankers viewed the existing system as corrupt and a restraint of trade. They formed a "Mercantile Committee" to advocate for Hill's plan and pushed for its adoption. In 1839, Hill was given a two-year contract to run the new system.

The Uniform Fourpenny Post

rate was introduced that lowered the cost to fourpence from 5 December 1839, then to the penny rate on 10 January 1840, even before stamps or letter sheets could be printed. The volume of paid internal correspondence increased dramatically, by 120%, between November 1839 and February 1840. This initial increase resulted from the elimination of "free franking" privileges and fraud.

Prepaid letter sheets, with a design by William Mulready

, were distributed in early 1840. These Mulready envelopes

were not popular and were widely satirised. According to a brochure distributed by the National Postal Museum (now the British Postal Museum & Archive), the Mulready envelopes threatened the livelihoods of stationery manufacturers, who encouraged the satires. They became so unpopular that the government used them on official mail and destroyed many others.

However, as a niche commercial publishing industry for machine-printed illustrated envelopes subsequently developed in Britain and elsewhere, it is likely that it was the sentiment of the illustration that provoked the ridicule and led to their withdrawal. Indeed in the absence of examples of machine-printed illustrated envelopes prior to this it may be appropriate to recognise the Mulready envelope as a significant innovation in its own right. Machine-printed illustrated envelopes are a mainstay of the direct mail

industry.

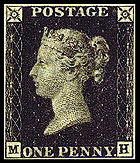

In May 1840, the world's first adhesive postage stamps were distributed. With an elegant engraving of the young Queen Victoria, the Penny Black

was an immediate success. Refinements, such as perforations to ease the separating of the stamps, would be instituted with later issues.

won re-election. Sir Robert Peel

returned to office between 30 August 1841 and 29 June 1846. Amid rancorous controversy, Hill was dismissed in July 1842. However, the London and Brighton Railway

named him a director and later chairman of the board, from 1843 to 1846. He lowered the fares from London to Brighton, expanded the routes, offered special excursion trains, and made the commute comfortable for passengers. In 1844 Edwin Chadwick

, Rowland Hill, John Stuart Mill

, Lyon Playfair

, Dr. Neill Arnott, and other friends formed a society called "Friends in Council," which met at each other's houses to discuss questions of political economy. Hill also became a member of the influential Political Economy Club

, founded by David Ricardo

and other classical economists, but now including many powerful businessmen and political figures.

In 1846, when the Conservatives left office, Hill became Secretary to the Postmaster General

, and then Secretary to the Post Office from 1854 until 1864. For his services Hill was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

in 1860. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society and was given an honorary degree from Oxford.

He died in Hampstead

, London in 1879. Sir Rowland Hill is buried in Westminster Abbey

; there is a memorial to him on his family grave in Highgate Cemetery

. There are streets named after him in Hampstead (running off Haverstock Hill, down the side of The Royal Free Hospital

), and Tottenham (off White Hart Lane

).

and the system of low and uniform postal rates, which is often taken for granted in the modern world. In this, he not only changed postal services around the world, but also made commerce more efficient and profitable, notwithstanding the fact that it took 30 years before the British Post Office's revenue recovered to the level it had been at in 1839. In fact the Uniform Penny Post continued in the UK into the 20th century, and at one point, one penny paid for up to four ounces.

There are three public statues of him. The first, sculpted by Sir Thomas Brock

and unveiled in 1881, stands in the town of his birthplace, Kidderminster. The second, by Edward Onslow Ford

stands at King Edward Street, London The third, less known, by Peter Hollins

, used to stand in Hurst Street

, Birmingham

but it is currently in the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

store. A life size white marble bust by W. D. Keyworth, Jr. may be viewed in St. Paul's Chapel, Westminster Abbey.

It Kidderminster, his birthplace he plays a large part in the local community history. A Wetherspoons

pub called The Penny Black is currently in the Town Centre and a large shopping mall connecting Vicar Street and the High Street is named after him, The Rowland Hill Shopping Centre.

At Tottenham

there is a local History Museum at Bruce Castle

(where Hill lived during the 1840s) including some relevant exhibits.

The Rowland Hill Awards

, started by the Royal Mail

and the British Philatelic Trust

in 1997, are annual awards for philatelic "innovation, initiative and enterprise."

In 1882, the Post Office instituted the Rowland Hill Fund for postal workers, pensioners and dependants in need.

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

, FRS (3 December 1795 - 27 August 1879) was an English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

teacher

Teacher

A teacher or schoolteacher is a person who provides education for pupils and students . The role of teacher is often formal and ongoing, carried out at a school or other place of formal education. In many countries, a person who wishes to become a teacher must first obtain specified professional...

, inventor and social reformer

Reform movement

A reform movement is a kind of social movement that aims to make gradual change, or change in certain aspects of society, rather than rapid or fundamental changes...

. He campaigned for a comprehensive reform of the postal system, based on the concept of penny postage and his solution of prepayment, facilitating the safe, speedy and cheap transfer of letters. Hill later served as a government postal official, and he is usually credited with originating the basic concepts of the modern postal service, including the invention of the postage stamp

Postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on an item of mail as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are made from special paper, with a national designation and denomination on the face, and a gum adhesive on the reverse side...

.

Earlier life

Hill was born in Blackwell Street, KidderminsterKidderminster

Kidderminster is a town, in the Wyre Forest district of Worcestershire, England. It is located approximately seventeen miles south-west of Birmingham city centre and approximately fifteen miles north of Worcester city centre. The 2001 census recorded a population of 55,182 in the town...

, Worcestershire

Worcestershire

Worcestershire is a non-metropolitan county, established in antiquity, located in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Warwickshire" NUTS 2 region...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. Rowland's father, Thomas Wright Hill

Thomas Wright Hill

Thomas Wright Hill was a mathematician and schoolmaster. He is credited as inventing the single transferable vote in 1819...

, was an innovator in education and politics, including among his friends Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

, Tom Paine and Richard Price

Richard Price

Richard Price was a British moral philosopher and preacher in the tradition of English Dissenters, and a political pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the American Revolution. He fostered connections between a large number of people, including writers of the...

. At the age of eleven, Rowland became a student-teacher in his father's school. He taught astronomy and earned extra money fixing scientific instruments. He also worked at the Assay Office

Birmingham Assay Office

The Birmingham Assay Office is one of the four remaining assay offices in the United Kingdom.The development of a silver industry in 18th century Birmingham was hampered by the legal requirement that items of solid silver be assayed, and the nearest Assay Offices were in Chester and London...

in Birmingham and painted landscapes in his spare time.

Educational reform

In 1819, he moved his father's school Hill Top from central Birmingham, establishing the Hazelwood School at EdgbastonEdgbaston

Edgbaston is an area in the city of Birmingham in England. It is also a formal district, managed by its own district committee. The constituency includes the smaller Edgbaston ward and the wards of Bartley Green, Harborne and Quinton....

, an affluent neighbourhood of Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

, as an “educational refraction of Priestley's ideas”. Hazelwood was to provide a model for public education

Public education

State schools, also known in the United States and Canada as public schools,In much of the Commonwealth, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, the terms 'public education', 'public school' and 'independent school' are used for private schools, that is, schools...

for the emerging middle classes, aiming for useful, pupil-centred education which would give sufficient knowledge, skills and understanding to allow a student to continue self-education through a life “most useful to society and most happy to himself”. The school, which Hill designed, included such marvels (for its time) as a science lab, a swimming pool, and forced air heating. In his Plans for the Government and Liberal Instruction of Boys in Large Numbers Drawn from Experience (1822, often cited as Public Education) he argued that kindness, instead of caning, and moral influence, rather than fear, should be the predominant forces in school discipline. Science was to be a compulsory subject, and students were to be self-governing.

Hazelwood gained international attention when French education leader and editor Marc Antoine Jullien

Marc-Antoine Jullien de Paris

Marc-Antoine Jullien, called Jullien fils, was a French revolutionary and man of letters.-Life:...

, former secretary to Robespierre, visited and wrote about the school in the June 1823 issue of his journal Revue encyclopédique. Jullien even transferred his son there. Hazelwood so impressed Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism...

that in 1827 a branch of the school was created at Bruce Castle

Bruce Castle

Bruce Castle is a Grade I listed 16th-century manor house in Lordship Lane, Tottenham, London. It is named after the House of Bruce who formerly owned the land on which it is built. Believed to stand on the site of an earlier building, about which little is known, the current house is one of the...

in Tottenham

Tottenham

Tottenham is an area of the London Borough of Haringey, England, situated north north east of Charing Cross.-Toponymy:Tottenham is believed to have been named after Tota, a farmer, whose hamlet was mentioned in the Domesday Book; hence Tota's hamlet became Tottenham...

, London. In 1833, the original Hazelwood School closed and its educational system was continued at the new Bruce Castle School

Bruce Castle School

Bruce Castle School, at Bruce Castle, Tottenham, was a progressive school for boys established in 1827 as an extension of Rowland Hill's Hazelwood School at Edgbaston...

of which Hill was head master from 1827 until 1839.

Colonisation of South Australia

The colonisation of South AustraliaSouth Australia

South Australia is a state of Australia in the southern central part of the country. It covers some of the most arid parts of the continent; with a total land area of , it is the fourth largest of Australia's six states and two territories.South Australia shares borders with all of the mainland...

was a project of Edward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield was a British politician, the driving force behind much of the early colonisation of South Australia, and later New Zealand....

, who believed that many of the social problems in Britain were caused by overcrowding and overpopulation. In 1832 Rowland Hill published a tract, entitled

Home colonies : sketch of a plan for the gradual extinction of pauperism, and for the diminution of crime, based on a Dutch model. Hill then served from 1833 until 1839 as secretary of the South Australian Colonization Commission, which worked successfully to establish a settlement without convicts at what is today Adelaide

Adelaide

Adelaide is the capital city of South Australia and the fifth-largest city in Australia. Adelaide has an estimated population of more than 1.2 million...

. The political economist, Robert Torrens

Robert Torrens (economist)

Colonel Robert Torrens was a Royal Marines officer, political economist, MP, owner of the influential Globe newspaper and prolific writer.Born in Ireland, son of Protestant Robert Torrens of Hervey Hill....

was chairman of the Commission. Under the South Australia Act 1834

South Australia Act 1834

The South Australia Colonisation Act 1834 is the short title of an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom with the long title...

, the colony was to embody the ideals and best qualities of British society, shaped by religious freedom and a commitment to social progress

Social progress

Social progress is the idea that societies can or do improve in terms of their social, political, and economic structures. This may happen as a result of direct human action, as in social enterprise or through social activism, or as a natural part of sociocultural evolution...

and civil liberties

Civil liberties

Civil liberties are rights and freedoms that provide an individual specific rights such as the freedom from slavery and forced labour, freedom from torture and death, the right to liberty and security, right to a fair trial, the right to defend one's self, the right to own and bear arms, the right...

.

Postal reform

Rowland Hill first started to take a serious interest in postal reforms in 1835. In 1836 Robert Wallace, MP, provided Hill with numerous books and documents, which Hill described as a “half hundred weight of material”. Hill commenced a detailed study of these documents and this led him to the publication, in early 1837, of a pamphlet entitled “Post Office Reform its Importance and Practicability”. He submitted a copy of this to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Thomas Spring-RiceThomas Spring Rice, 1st Baron Monteagle of Brandon

Thomas Spring Rice, 1st Baron Monteagle of Brandon, PC, FRS was a British Whig politician, who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1835 to 1839.-Background:...

, on 4 January 1837. This first edition was marked “private and confidential” and was not released to the general public. The Chancellor summoned Hill to a meeting during which the Chancellor suggested improvements, asked for reconsiderations and requested a supplement which Hill duly produced and supplied on 28 January 1837.

In the 1830s at least 12½% of all British mail was conveyed under the personal frank of peers, dignitaries and Members of Parliament, while censorship and political espionage were conducted by postal officials. Fundamentally, the postal system was mismanaged, wasteful, expensive and slow. It had become inadequate for the needs of an expanding commercial and industrial nation. There is a well-known story, probably apocryphal, about how Hill gained an interest in reforming the postal system; he apparently noticed a young woman too poor to redeem a letter sent to her by her fiancé. At that time, letters were normally paid for by the recipient, not the sender. The recipient could simply refuse delivery. Frauds were commonplace; for example, coded information could appear on the cover of the letter; the recipient would examine the cover to gain the information, and then refuse delivery to avoid payment. Each individual letter had to be logged. In addition, postal rates were complex, depending on the distance and the number of sheets in the letter.

Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden

Richard Cobden was a British manufacturer and Radical and Liberal statesman, associated with John Bright in the formation of the Anti-Corn Law League as well as with the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty...

and John Ramsey McCulloch, both advocates of free trade, attacked the policies of privilege and protection of the Tory government. McCulloch, in 1833, advanced the view that "nothing contributes more to facilitate commerce than the safe, speedy and cheap conveyance of letters."

Hill's famous pamphlet, Post Office Reform: its Importance and Practicability, referred to above, was privately circulated in 1837. The report called for "low and uniform rates" according to weight, rather than distance. Hill's study showed that most of the costs in the postal system were not for transport, but rather for laborious handling procedures at the origins and the destinations. Costs could be reduced dramatically if postage were prepaid by the sender, the prepayment to be proven by the use of prepaid letter sheets or adhesive stamps (adhesive stamps had long been used to show payment of taxes, on documents for example). Letter sheet

Letter sheet

In philatelic terminology a Letter sheet, often written lettersheet, is nowadays an item of postal stationery issued by a postal authority. It is a sheet of paper that can be folded, usually sealed , and mailed without the use of an envelope...

s were to be used because envelopes were not yet common; they were not yet mass-produced, and in an era when postage was calculated partly on the basis of the number of sheets of paper used, the same sheet of paper would be folded and serve for both the message and the address. In addition, Hill proposed to lower the postage rate to a penny per half ounce, without regard to distance. He first presented his proposal to the Government in 1837.

Thomas Anson, 1st Earl of Lichfield

Thomas William Anson, 1st Earl of Lichfield PC , known as The Viscount Anson from 1818 to 1831, was a British Whig politician. He served under Lord Grey and Lord Melbourne as Master of the Buckhounds between 1830 and 1834 and under Melbourne Postmaster General between 1835 and 1841...

, thundered about Hill's "wild and visionary schemes." William Leader Maberly

William Leader Maberly

William Leader Maberly spent most of his life as a British army officer and Whig politician.He was the eldest child of John Maberly , a currier, clothing manufacturer, banker and MP, who had made and lost a fortune in a lifetime....

, Secretary to the Post Office, denounced Hill's study: "This plan appears to be a preposterous one, utterly unsupported by facts and resting entirely on assumption". But merchants, traders and bankers viewed the existing system as corrupt and a restraint of trade. They formed a "Mercantile Committee" to advocate for Hill's plan and pushed for its adoption. In 1839, Hill was given a two-year contract to run the new system.

The Uniform Fourpenny Post

Uniform Fourpenny Post

The Uniform Fourpenny Post was a short-lived uniform pre-paid letter rate in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that lasted for only 36 days from 5 December 1839 until 9 January 1840...

rate was introduced that lowered the cost to fourpence from 5 December 1839, then to the penny rate on 10 January 1840, even before stamps or letter sheets could be printed. The volume of paid internal correspondence increased dramatically, by 120%, between November 1839 and February 1840. This initial increase resulted from the elimination of "free franking" privileges and fraud.

Prepaid letter sheets, with a design by William Mulready

William Mulready

William Mulready was an Irish genre painter living in London. He is best known for his romanticizing depictions of rural scenes, and for creating Mulready stationery letter sheets, issued at the same time as the Penny Black postage stamp.-Life and family:William Mulready was born in Ennis, County...

, were distributed in early 1840. These Mulready envelopes

Mulready stationery

Mulready stationery describes the postal stationery lettersheets and pre-gummed envelopes that were introduced as part of the British Post Office postal reforms of 1840. They went on sale on 1 May, 1840, and were valid for use from 6 May...

were not popular and were widely satirised. According to a brochure distributed by the National Postal Museum (now the British Postal Museum & Archive), the Mulready envelopes threatened the livelihoods of stationery manufacturers, who encouraged the satires. They became so unpopular that the government used them on official mail and destroyed many others.

However, as a niche commercial publishing industry for machine-printed illustrated envelopes subsequently developed in Britain and elsewhere, it is likely that it was the sentiment of the illustration that provoked the ridicule and led to their withdrawal. Indeed in the absence of examples of machine-printed illustrated envelopes prior to this it may be appropriate to recognise the Mulready envelope as a significant innovation in its own right. Machine-printed illustrated envelopes are a mainstay of the direct mail

Direct mail

Advertising mail, also known as direct mail, junk mail, or admail, is the delivery of advertising material to recipients of postal mail. The delivery of advertising mail forms a large and growing service for many postal services, and direct-mail marketing forms a significant portion of the direct...

industry.

In May 1840, the world's first adhesive postage stamps were distributed. With an elegant engraving of the young Queen Victoria, the Penny Black

Penny Black

The Penny Black was the world's first adhesive postage stamp used in a public postal system. It was issued in Britain on 1 May 1840, for official use from 6 May of that year....

was an immediate success. Refinements, such as perforations to ease the separating of the stamps, would be instituted with later issues.

Later life

Rowland Hill continued at the Post Office until the Conservative PartyConservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

won re-election. Sir Robert Peel

Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 December 1834 to 8 April 1835, and again from 30 August 1841 to 29 June 1846...

returned to office between 30 August 1841 and 29 June 1846. Amid rancorous controversy, Hill was dismissed in July 1842. However, the London and Brighton Railway

London and Brighton Railway

The London and Brighton Railway was a railway company in England which was incorporated in 1837 and survived until 1846. Its railway runs from a junction with the London & Croydon Railway at Norwood - which gives it access from London Bridge, just south of the River Thames in central London...

named him a director and later chairman of the board, from 1843 to 1846. He lowered the fares from London to Brighton, expanded the routes, offered special excursion trains, and made the commute comfortable for passengers. In 1844 Edwin Chadwick

Edwin Chadwick

Sir Edwin Chadwick KCB was an English social reformer, noted for his work to reform the Poor Laws and improve sanitary conditions and public health...

, Rowland Hill, John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill was a British philosopher, economist and civil servant. An influential contributor to social theory, political theory, and political economy, his conception of liberty justified the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state control. He was a proponent of...

, Lyon Playfair

Lyon Playfair, 1st Baron Playfair

Lyon Playfair, 1st Baron Playfair GCB, PC, FRS was a Scottish scientist and Liberal politician.-Background and education:...

, Dr. Neill Arnott, and other friends formed a society called "Friends in Council," which met at each other's houses to discuss questions of political economy. Hill also became a member of the influential Political Economy Club

Political Economy Club

The Political Economy Club was founded by James Mill and a circle of friends in 1821 in London, for the purpose of coming to an agreement on the fundamental principles of political economy...

, founded by David Ricardo

David Ricardo

David Ricardo was an English political economist, often credited with systematising economics, and was one of the most influential of the classical economists, along with Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith, and John Stuart Mill. He was also a member of Parliament, businessman, financier and speculator,...

and other classical economists, but now including many powerful businessmen and political figures.

In 1846, when the Conservatives left office, Hill became Secretary to the Postmaster General

United Kingdom Postmaster General

The Postmaster General of the United Kingdom is a defunct Cabinet-level ministerial position in HM Government. Aside from maintaining the postal system, the Telegraph Act of 1868 established the Postmaster General's right to exclusively maintain electric telegraphs...

, and then Secretary to the Post Office from 1854 until 1864. For his services Hill was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate mediæval ceremony for creating a knight, which involved bathing as one of its elements. The knights so created were known as Knights of the Bath...

in 1860. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society and was given an honorary degree from Oxford.

He died in Hampstead

Hampstead

Hampstead is an area of London, England, north-west of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Camden in Inner London, it is known for its intellectual, liberal, artistic, musical and literary associations and for Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland...

, London in 1879. Sir Rowland Hill is buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

; there is a memorial to him on his family grave in Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a cemetery located in north London, England. It is designated Grade I on the English Heritage Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England. It is divided into two parts, named the East and West cemetery....

. There are streets named after him in Hampstead (running off Haverstock Hill, down the side of The Royal Free Hospital

Royal Free Hospital

The Royal Free Hospital is a major teaching hospital in Hampstead, London, England and part of the Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust....

), and Tottenham (off White Hart Lane

White Hart Lane

White Hart Lane is an all-seater football stadium in Tottenham, London, England. Built in 1899, it is the home of Tottenham Hotspur and, after numerous renovations, the stadium has a capacity of 36,230....

).

Legacy

Hill's legacies are twofold: the first was his model for education of the emerging middle classes. The second was his model for an efficient postal system to serve business and the public, including the postage stampPostage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on an item of mail as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are made from special paper, with a national designation and denomination on the face, and a gum adhesive on the reverse side...

and the system of low and uniform postal rates, which is often taken for granted in the modern world. In this, he not only changed postal services around the world, but also made commerce more efficient and profitable, notwithstanding the fact that it took 30 years before the British Post Office's revenue recovered to the level it had been at in 1839. In fact the Uniform Penny Post continued in the UK into the 20th century, and at one point, one penny paid for up to four ounces.

There are three public statues of him. The first, sculpted by Sir Thomas Brock

Thomas Brock

Sir Thomas Brock KCB RA was an English sculptor.- Life :Brock was born in Worcester, attended the School of Design in Worcester and then undertook an apprenticeship in modelling at the Worcester Royal Porcelain Works. In 1866 he became a pupil of the sculptor John Henry Foley. He married in 1869,...

and unveiled in 1881, stands in the town of his birthplace, Kidderminster. The second, by Edward Onslow Ford

Edward Onslow Ford

Edward Onslow Ford , English sculptor, was born in London. He received some education as a painter in Antwerp and as a sculptor in Munich under Professor Wagmuller, but was mainly self-taught....

stands at King Edward Street, London The third, less known, by Peter Hollins

Peter Hollins

Peter Hollins was an English sculptor.Born in Birmingham, the son of the architect and sculptor William Hollins, Hollins studied drawing under Vincent Barber and sculpture in his father's studio before moving to London to work for Francis Chantrey in 1822...

, used to stand in Hurst Street

Hurst Street

Hurst Street is a street located in Birmingham City Centre, England.Hurst Street is the location of the Birmingham Hippodrome, a theatre specialising in ballet, opera, and musicals. It is the home of the Birmingham Royal Ballet. Adjacent to the Hippodrome, across and on the corner of Inge Street,...

, Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

but it is currently in the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery is a museum and art gallery in Birmingham, England.Entrance to the Museum and Art Gallery is free, but some major exhibitions in the Gas Hall incur an entrance fee...

store. A life size white marble bust by W. D. Keyworth, Jr. may be viewed in St. Paul's Chapel, Westminster Abbey.

It Kidderminster, his birthplace he plays a large part in the local community history. A Wetherspoons

Wetherspoons

J D Wetherspoon plc is a British pub chain based in Watford. Founded as a single pub in 1979 by Tim Martin, the company now owns 815 outlets. The chain champions cask ale, low prices, long opening hours, and no music. The company also operates the Lloyds No...

pub called The Penny Black is currently in the Town Centre and a large shopping mall connecting Vicar Street and the High Street is named after him, The Rowland Hill Shopping Centre.

At Tottenham

Tottenham

Tottenham is an area of the London Borough of Haringey, England, situated north north east of Charing Cross.-Toponymy:Tottenham is believed to have been named after Tota, a farmer, whose hamlet was mentioned in the Domesday Book; hence Tota's hamlet became Tottenham...

there is a local History Museum at Bruce Castle

Bruce Castle

Bruce Castle is a Grade I listed 16th-century manor house in Lordship Lane, Tottenham, London. It is named after the House of Bruce who formerly owned the land on which it is built. Believed to stand on the site of an earlier building, about which little is known, the current house is one of the...

(where Hill lived during the 1840s) including some relevant exhibits.

The Rowland Hill Awards

Rowland Hill Awards

The Rowland Hill Awards were established in 1997 as a joint venture between Britain's Royal Mail, the British Philatelic Trust and the Association of British Philatelic Societies....

, started by the Royal Mail

Royal Mail

Royal Mail is the government-owned postal service in the United Kingdom. Royal Mail Holdings plc owns Royal Mail Group Limited, which in turn operates the brands Royal Mail and Parcelforce Worldwide...

and the British Philatelic Trust

British Philatelic Trust

The British Philatelic Trust was established in 1981 by the British Post Office. The governing deed was executed on 26 September 1983. The Trust is independent and was registered as an educational charity on 21 November 1983.- Origins :...

in 1997, are annual awards for philatelic "innovation, initiative and enterprise."

In 1882, the Post Office instituted the Rowland Hill Fund for postal workers, pensioners and dependants in need.