Robert Jefferson Breckinridge

Encyclopedia

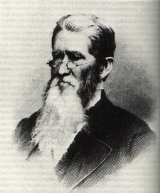

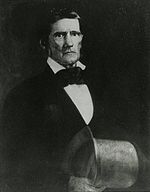

Robert Jefferson Breckinridge (March 8, 1800 – December 27, 1871) was a politician

and Presbyterian

minister. He was a member of the Breckinridge family

of Kentucky

, the son of Senator

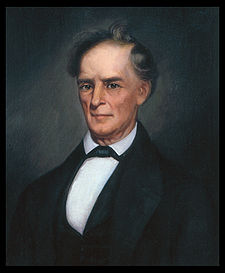

John Breckinridge

.

A restless youth, Breckinridge was suspended from Princeton University

for fighting, and following his graduation from Union College

in 1819, was prone to engage in a lifestyle of partying and revelry. Nevertheless, he was admitted to the bar

in 1824 and elected to the Kentucky General Assembly

in 1825. A serious illness and the death of a child in 1829 prompted him to turn to religion, and he became an ordained minister in 1832.

Breckinridge accepted the call to pastor the Second Presbyterian Church of Baltimore, Maryland in 1832. While at the church, he became involved in a number of theological debates. During the Old School-New School controversy within the Presbyterian Church in the 1830s, Breckinridge became a hard-line member of the Old School faction, and played an influential role in the ejection of several churches in 1837. He was rewarded for his stances by being elected moderator of the Presbyterian Church's General Assembly in 1841.

After a brief stint as president of Jefferson College

in Pennsylvania

, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky, where he pastored the First Presbyterian church of Lexington, Kentucky

and was appointed superintendent of public education by Governor William Owsley

. The changes he effected in this office brought a tenfold increase in public school attendance and led to him being called the father of the public school system in Kentucky

. He left his post as superintendent after six years to become a professor at Danville Theological Seminary in Danville, Kentucky

.

As the sectional conflict leading up to the Civil War

escalated, Breckinridge was put in the unusual position of being a slaveholder who opposed slavery. His support of Abraham Lincoln

for president in the election of 1860

put him at odds with his nephew, John C. Breckinridge

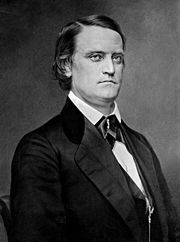

. The tragic scenario of brother against brother

literally played out in Breckinridge's family, with two of his sons joining each side during the war. Following the war, Breckinridge retired to his home in Danville, where he died on December 27, 1871.

. He was the third son born to John and Mary Hopkins (Cabell) Breckinridge. Senator Breckinridge died in 1806, leaving his wife to tend the family's large plantations. Robert soon earned a reputation of misbehaving. In one instance, he and his brother John had a physical altercation because Robert put salt

in a blind

cousin's coffee

; in another, his mother gave him a "tremendous whipping" for beating an old slave.

Breckinridge studied education at a classical school operated by Dr. Louis Marshall, the brother of Chief Justice

John Marshall

, then followed his brothers, Cabell and John, to Princeton

in 1817. His behavior problems continued there; in one year, he spent more than twelve hundred dollars. He was suspended for fighting, and although he was later reinstated, the incident soured him on the Princeton, and he was granted an honorable release. (The school awarded him an honorary

Master of Arts

degree in 1832.) He enrolled at Yale University

, but after three months, discovered that a one year residency was required for graduation. Unwilling to complete this requirement, he move to Union College

in Schenectady, New York

where he earned a Bachelor of Arts

degree in 1819.

Following his graduation, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky with no clear direction in his life. He began to amuse himself by attending various parties and other social engagements. During a visit to the state capital, he so offended one man that he was challenged to a duel

. Though he obtained two pistols, he never accepted the man's challenge, and was branded a coward. The dispute was later settled in the Masonic Lodge

of which both Breckinridge and the other man were members.

On March 11, 1823, Breckinridge married his cousin, Ann Sophonisba Preston at the bride's home in Abingdon, Virginia

; the couple had eleven children. Ann's political heritage rivaled that of her husband. A grandniece of Patrick Henry

, she was also a sister to Senator William Campbell Preston and a sister-in-law to South Carolina governor

Wade Hampton III

, and Virginia governors

John B. Floyd

and James McDowell

.

Following the advice of his older brother, Breckinridge obtained his law license on January 3, 1824, but the practice of law did not suit him. He instead decided to follow the family tradition and seek public office, campaigning for a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives

Following the advice of his older brother, Breckinridge obtained his law license on January 3, 1824, but the practice of law did not suit him. He instead decided to follow the family tradition and seek public office, campaigning for a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives

. Even in his early political career, he began to articulate his stance on the issues that would become his legacy. First, he shunned the states' rights

viewpoint, stressing instead the need for a strong interdependence between the states. Second, he called for an end to slavery. Third, he emphasized the importance of education. Though they agreed on this last point, Breckinridge's father had ardently opposed emancipation of slaves and favored states' rights. Historian James Klotter opines that Louis Marshall and Robert's mother, Mary, may have influenced his positions.

The most politically-charged issue in Kentucky during Breckinridge's campaign, however, was the Old Court-New Court controversy

. The Panic of 1819

had left many Kentuckians in dire financial straits. Legislators sought to relieve some of the financial burden by passing a law of replevin

which favored debtors. The Kentucky Court of Appeals, (the highest court in the Commonwealth at the time,) declared the law unconstitutional. The next year, an incensed General Assembly passed legislation that dissolved the court and replaced it with a new court. Neither court acknowledged the other as valid, and a confused public lost respect for public authority in general. The issue was generally split along party lines, with Democrats

generally favoring the New Court and Whigs

favoring the Old Court.

Breckinridge was able to dodge the issue during the campaign, which he won in 1825, but once he took office, he had to come down on one side or the other. He voted in favor of the Old Court, reflecting his upper class status and affinity for the establishment. In so doing, he identified himself with the party of Kentucky's favorite son, Henry Clay

. The Whigs would control Kentucky politics for the next twenty-five years. In 1826, the majority of the General Assembly sided with the Old Court and abolished the New Court.

Eventually, tensions faded, but a bigger decision awaited Robert Breckinridge in 1828. He was chosen to sit on a committee that would draft Kentucky's response to the Nullification Crisis

. Because much of South Carolina

's reasoning for their actions was based on the logic of the Kentucky Resolutions, which were supported by Senator John Breckinridge, Robert Breckinridge now had to determine whether he should support the words of his late father or refute them. In the end, his Unionist sympathies overrode his sense of loyalty to his father; he sided with the committee's majority in condemning South Carolina's actions.

. In an 1828 letter to his wife, who was visiting relatives in Virginia

, he recounted that he had been bedridden and near death for two months. Finally, in February 1829, the illness subsided. Only then could he be told about the death of his daughter, Louisiana, which had occurred a month earlier. The illness, combined with the news of the death of his daughter, caused Breckinridge turn to religion. In spring 1829, he made a public profession of his faith, and in 1831, he hosted a revival meeting on his farm during which he decided to pursue ministerial training under the West Lexington Presbytery. He was ordained as a Presbyterian minister on April 5, 1832.

Breckinridge served as a Ruling Elder at the Presbyterian General Assembly of 1832, then relocated to Princeton, New Jersey

to study under Samuel Miller at Princeton Theological Seminary

. In November 1832, he succeeded his brother John as pastor of Second Presbyterian Church of Baltimore, Maryland. His tenure saw numerous converts, but he was put at odds with his brother and Samuel Miller over practices employed in his church. His counselors were also concerned that he was wavering on his belief in the doctrine of limited atonement

. Eventually, he was persuaded back into the doctrines of the orthodox Calvinism

and became one of the leaders of the Old School Presbyterian movement.

Now solidly in the Presbyterian fold, Breckinridge began to follow in the footsteps of his brother John, criticizing Roman Catholicism in a number of his speeches and publications. He sponsored and edited two "thoroughly Protestant

" journals – the Baltimore Literary and Religious magazine and the Spirit of the XIX Century. A year-long tour of Europe

with his wife that began in April 1836 deepened his disdain for the denomination; he opined that most of the continent's ills could be traced back to Catholic "superstitions." A particularly harsh missive against a Catholic who worked in the county almshouse

drew an indictment for libel in 1840. The trial ended in a hung jury

that voted 10–2 in favor of acquittal. Though displeased that he could not obtain a unanimous acquittal, Breckinridge continued undaunted. In 1841, he published several of his anti-Catholic articles as Papism in the XIX Century in the United States.

Breckinridge was equally controversial in internal church politics. He rebuked the Synod of the Western Reserve for de-emphasizing and effectively abandoning the office of Ruling Elder. He also condemned the governance of Presbyterian missionaries

by anyone other than the Presbyterian church. In 1834, he was the chief author of the Act and Testimony, a document summarizing the contentions between the Old and New Schools. The New School resented Breckinridge and those who signed the Act and Testimony, and even some in the Old School camp had hoped for a more moderate course. The differences between the Old and New Schools widened over the teachings of Albert Barnes, and the New School members were ejected from the Presbyterian Church in 1837. Because of his leadership in the Old School-New School controversy, Breckinridge was rewarded by being elected moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly in 1841.

In 1844, Breckinridge's wife Ann died. Lingering sadness and memories of his and Ann's life in Baltimore may have led him to leave the city and the pastorate he had held for twelve years. He was offered pastorate of the Second Presbyterian Church of Lexington, Kentucky, but instead, accepted the presidency of Jefferson College in Pennsylvania

In 1844, Breckinridge's wife Ann died. Lingering sadness and memories of his and Ann's life in Baltimore may have led him to leave the city and the pastorate he had held for twelve years. He was offered pastorate of the Second Presbyterian Church of Lexington, Kentucky, but instead, accepted the presidency of Jefferson College in Pennsylvania

in 1845 against the advice of his brothers John and William. A rift between Breckinridge and his brother Cabell's widow and other relatives may help account for this surprising decision. He did not feel he could yet return to his home state.

Breckinridge was inaugurated as president of Jefferson College on September 27, 1845. During his tenure, he also pastored a church in the city of Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

. College administration apparently did not suit him, however. A student uprising against the president and the faculty occurred in 1846, hastening the end of his short stay at the school. A desire to see his children, most of whom were living with relatives scattered throughout Kentucky and Virginia, also factored into his decision to resign his post in 1847. On his resignation, he was awarded an honorary

LL.D from the school.

Breckinridge would now return to Kentucky, accepting the pastorate of First Presbyterian Church of Lexington. His return to Kentucky was also motivated by a growing fondness for his cousin, Virginia Hart Shelby, who had cared for two of his children during his stay in Pennsylvania. Virginia was the widow of Alfred Shelby, the son of twice governor of Kentucky, Isaac Shelby

Breckinridge would now return to Kentucky, accepting the pastorate of First Presbyterian Church of Lexington. His return to Kentucky was also motivated by a growing fondness for his cousin, Virginia Hart Shelby, who had cared for two of his children during his stay in Pennsylvania. Virginia was the widow of Alfred Shelby, the son of twice governor of Kentucky, Isaac Shelby

. Their written exchanges included love poems from Robert and concerned questions from Virginia about the wisdom of engaging in a relationship. Despite being advised by her sisters to avoid the marriage and her own open wavering on the issue, the two were married in April 1847. They had three children, only one of whom survived to adulthood. Disagreements among the children of both partners' previous marriages exacerbated an already tense union, which almost ended in divorce in September 1856. Nevertheless, Robert managed to reconcile with his wife, and they remained together until Virginia's death in 1859.

Oddly, Breckinridge's personal turmoil did not hinder his political accomplishments. He was appointed superintendent of public education by Governor William Owsley

. He was the sixth person to hold the office since its creation in the 1830s. The task was daunting. Only one out of every ten school-age children in Kentucky ever attended school, and at least thirty Kentucky counties had received no state educational funds since 1840.

Breckinridge began reforms immediately and zealously. He secured the General Assembly's passage of a two-cent property tax for education. The tax was subject to voter approval, and Breckinridge worked hard to publicize the issue. His efforts paid off, as the tax passed by almost a two-to-one margin. Continuing to publicize needs and push legislators to action, Breckinridge enjoyed the support of five of the six governors under whom he served. Only John L. Helm

, who opposed a state-funded school system, challenged him, but Helm's veto

of a Breckinridge educational bill was overridden in the General Assembly. Breckinridge's reforms manifested tangible results. From 1847 to 1850, educational spending increased from $6,000 to $144,000. By 1850, only one out of every ten school age children did not attend school.

In 1850, Kentuckians ratified their third constitution

. One of many changes effected by this document was that the office of superintendent became elective. Though the election belonged to the Democrats, Breckinridge, a Whig, was elected over five challengers for the office. His tenure would be a short one, however. Unlike his early reforms, his calls for parental selection of textbooks and use of the Bible

as the primary reading material were not heeded. He also opposed the abolition of tuition charges and unsuccessfully lobbied for a pay increase for his position. (The salary was only $750.) With little prospect of further reform under his leadership, Breckinridge resigned in 1853.

Following his resignation, Breckinridge's party affiliation progressed from Whig

to Know-Nothing to Republican

. In 1853, helped found Danville Theological Seminary in Danville, Kentucky

, becoming a Professor of Exegetic, Didactic and Polemic Theology.

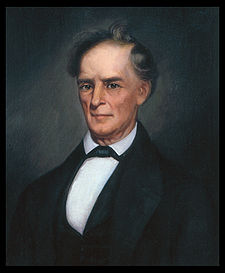

Although he owned a number of slaves, and his marriage to Virginia Shelby had left him with a good many more, Breckinridge had been a supporter of gradual emancipation and colonization of blacks since his early political career. As the sectional crisis worsened, this led him into several high-profile debates, notably with fellow Kentuckian Robert Wickliffe. His support of Abraham Lincoln

Although he owned a number of slaves, and his marriage to Virginia Shelby had left him with a good many more, Breckinridge had been a supporter of gradual emancipation and colonization of blacks since his early political career. As the sectional crisis worsened, this led him into several high-profile debates, notably with fellow Kentuckian Robert Wickliffe. His support of Abraham Lincoln

for president in the election of 1860

pitted him against his own nephew, Vice President John C. Breckinridge

.

At the outbreak of the Civil War

, Breckinridge quickly became an ardent supporter of the Union, not for its position against slavery, but for the sake of preserving the Union. He used his position as editor of the Danville Quarterly Review to advocate his position. He called for harsh measures against secession, and in time, accepted President

Lincoln's immediate emancipation of slaves. He was chosen as the temporary chair of the 1864 Republican National Convention

that re-nominated Lincoln for president, and his pro-Union speech was hailed by freshman Representative

James G. Blaine

as one of the most inspiring given at the event.

Breckinridge's family split on the issue, with two of his sons – Joseph

and Charles – fighting for the Union cause, and two – Willie

and Robert Jr.

– fighting for the Confederacy

. While three of his sons-in-law also fought for the Union, daughter Sophonisba

's husband, Theophilus Steele, rode with John Hunt Morgan

, and it is likely that Robert Breckinridge's intervention kept him from being executed by Edwin M. Stanton

. Following the war, Willie Breckinridge's wife Issa refused to let her father-in-law see two of his grandchildren for a period of two years.

On November 5, 1868, Breckinridge married his third wife, Margaret Faulkner White. A year later, he resigned his professorship at Danville Seminary. He died on December 27, 1871 after an extensive illness, and was buried in Lexington Cemetery.

in Danville - Breckinridge's nephew John C. Breckinridge

's alma mater. Breckinridge Hall was renovated in 1999, and is on the National Register of Historic Places

. http://www.centre.edu/campusbuildings/slideshow_breck/index.html

Breckinridge Hall, a three-story building on Morehead State University's campus, is named for Robert J. Breckinridge.

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

and Presbyterian

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

minister. He was a member of the Breckinridge family

Breckinridge family

The Breckinridge family is a family of politicians and public figures from the United States. The family has included six members of the United States House of Representatives, two United States Senators, a cabinet member, two Ambassadors, a Vice President of United States and an unsuccessful...

of Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, the son of Senator

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

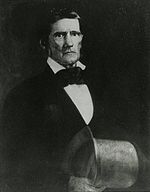

John Breckinridge

John Breckinridge (1760-1806)

John Breckinridge was a United States Senator and Attorney General. He was the progenitor of the Breckinridge political family.-Early Life in Virginia:...

.

A restless youth, Breckinridge was suspended from Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

for fighting, and following his graduation from Union College

Union College

Union College is a private, non-denominational liberal arts college located in Schenectady, New York, United States. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents. In the 19th century, it became the "Mother of Fraternities", as...

in 1819, was prone to engage in a lifestyle of partying and revelry. Nevertheless, he was admitted to the bar

Bar (law)

Bar in a legal context has three possible meanings: the division of a courtroom between its working and public areas; the process of qualifying to practice law; and the legal profession.-Courtroom division:...

in 1824 and elected to the Kentucky General Assembly

Kentucky General Assembly

The Kentucky General Assembly, also called the Kentucky Legislature, is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Kentucky.The General Assembly meets annually in the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky, convening on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in January...

in 1825. A serious illness and the death of a child in 1829 prompted him to turn to religion, and he became an ordained minister in 1832.

Breckinridge accepted the call to pastor the Second Presbyterian Church of Baltimore, Maryland in 1832. While at the church, he became involved in a number of theological debates. During the Old School-New School controversy within the Presbyterian Church in the 1830s, Breckinridge became a hard-line member of the Old School faction, and played an influential role in the ejection of several churches in 1837. He was rewarded for his stances by being elected moderator of the Presbyterian Church's General Assembly in 1841.

After a brief stint as president of Jefferson College

Washington & Jefferson College

Washington & Jefferson College, also known as W & J College or W&J, is a private liberal arts college in Washington, Pennsylvania, in the United States, which is south of Pittsburgh...

in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky, where he pastored the First Presbyterian church of Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

and was appointed superintendent of public education by Governor William Owsley

William Owsley

William Owsley was an associate justice on the Kentucky Court of Appeals and the 16th Governor of Kentucky. He also served in both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly and was Kentucky Secretary of State under Governor James Turner Morehead.Owsley studied law under John Boyle...

. The changes he effected in this office brought a tenfold increase in public school attendance and led to him being called the father of the public school system in Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

. He left his post as superintendent after six years to become a professor at Danville Theological Seminary in Danville, Kentucky

Danville, Kentucky

Danville is a city in and the county seat of Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 16,218 at the 2010 census.Danville is the principal city of the Danville Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Boyle and Lincoln counties....

.

As the sectional conflict leading up to the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

escalated, Breckinridge was put in the unusual position of being a slaveholder who opposed slavery. His support of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

for president in the election of 1860

United States presidential election, 1860

The United States presidential election of 1860 was a quadrennial election, held on November 6, 1860, for the office of President of the United States and the immediate impetus for the outbreak of the American Civil War. The nation had been divided throughout the 1850s on questions surrounding the...

put him at odds with his nephew, John C. Breckinridge

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Kentucky and was the 14th Vice President of the United States , to date the youngest vice president in U.S...

. The tragic scenario of brother against brother

Brother against brother

"Brother against brother" is a slogan used in histories of the American Civil War, describing the predicament faced in families in which loyalties and military service were divided between the Union and the Confederacy...

literally played out in Breckinridge's family, with two of his sons joining each side during the war. Following the war, Breckinridge retired to his home in Danville, where he died on December 27, 1871.

Early life

Robert Breckinridge was born March 8, 1800 at Cabell's Dale near Lexington, KentuckyLexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

. He was the third son born to John and Mary Hopkins (Cabell) Breckinridge. Senator Breckinridge died in 1806, leaving his wife to tend the family's large plantations. Robert soon earned a reputation of misbehaving. In one instance, he and his brother John had a physical altercation because Robert put salt

Salt

In chemistry, salts are ionic compounds that result from the neutralization reaction of an acid and a base. They are composed of cations and anions so that the product is electrically neutral...

in a blind

Blindness

Blindness is the condition of lacking visual perception due to physiological or neurological factors.Various scales have been developed to describe the extent of vision loss and define blindness...

cousin's coffee

Coffee

Coffee is a brewed beverage with a dark,init brooo acidic flavor prepared from the roasted seeds of the coffee plant, colloquially called coffee beans. The beans are found in coffee cherries, which grow on trees cultivated in over 70 countries, primarily in equatorial Latin America, Southeast Asia,...

; in another, his mother gave him a "tremendous whipping" for beating an old slave.

Breckinridge studied education at a classical school operated by Dr. Louis Marshall, the brother of Chief Justice

Chief Justice of the United States

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

John Marshall

John Marshall

John Marshall was the Chief Justice of the United States whose court opinions helped lay the basis for American constitutional law and made the Supreme Court of the United States a coequal branch of government along with the legislative and executive branches...

, then followed his brothers, Cabell and John, to Princeton

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

in 1817. His behavior problems continued there; in one year, he spent more than twelve hundred dollars. He was suspended for fighting, and although he was later reinstated, the incident soured him on the Princeton, and he was granted an honorable release. (The school awarded him an honorary

Honorary degree

An honorary degree or a degree honoris causa is an academic degree for which a university has waived the usual requirements, such as matriculation, residence, study, and the passing of examinations...

Master of Arts

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

degree in 1832.) He enrolled at Yale University

Yale University

Yale University is a private, Ivy League university located in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701 in the Colony of Connecticut, the university is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States...

, but after three months, discovered that a one year residency was required for graduation. Unwilling to complete this requirement, he move to Union College

Union College

Union College is a private, non-denominational liberal arts college located in Schenectady, New York, United States. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents. In the 19th century, it became the "Mother of Fraternities", as...

in Schenectady, New York

Schenectady, New York

Schenectady is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 66,135...

where he earned a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts , from the Latin artium baccalaureus, is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate course or program in either the liberal arts, the sciences, or both...

degree in 1819.

Following his graduation, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky with no clear direction in his life. He began to amuse himself by attending various parties and other social engagements. During a visit to the state capital, he so offended one man that he was challenged to a duel

Duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two individuals, with matched weapons in accordance with agreed-upon rules.Duels in this form were chiefly practised in Early Modern Europe, with precedents in the medieval code of chivalry, and continued into the modern period especially among...

. Though he obtained two pistols, he never accepted the man's challenge, and was branded a coward. The dispute was later settled in the Masonic Lodge

Freemasonry

Freemasonry is a fraternal organisation that arose from obscure origins in the late 16th to early 17th century. Freemasonry now exists in various forms all over the world, with a membership estimated at around six million, including approximately 150,000 under the jurisdictions of the Grand Lodge...

of which both Breckinridge and the other man were members.

On March 11, 1823, Breckinridge married his cousin, Ann Sophonisba Preston at the bride's home in Abingdon, Virginia

Abingdon, Virginia

Abingdon is a town in Washington County, Virginia, USA, 133 miles southwest of Roanoke. The population was 8,191 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Washington County and is a designated Virginia Historic Landmark...

; the couple had eleven children. Ann's political heritage rivaled that of her husband. A grandniece of Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry was an orator and politician who led the movement for independence in Virginia in the 1770s. A Founding Father, he served as the first and sixth post-colonial Governor of Virginia from 1776 to 1779 and subsequently, from 1784 to 1786...

, she was also a sister to Senator William Campbell Preston and a sister-in-law to South Carolina governor

Governor of South Carolina

The Governor of the State of South Carolina is the head of state for the State of South Carolina. Under the South Carolina Constitution, the Governor is also the head of government, serving as the chief executive of the South Carolina executive branch. The Governor is the ex officio...

Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III

Wade Hampton III was a Confederate cavalry leader during the American Civil War and afterward a politician from South Carolina, serving as its 77th Governor and as a U.S...

, and Virginia governors

Governor of Virginia

The governor of Virginia serves as the chief executive of the Commonwealth of Virginia for a four-year term. The position is currently held by Republican Bob McDonnell, who was inaugurated on January 16, 2010, as the 71st governor of Virginia....

John B. Floyd

John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.-Early life:...

and James McDowell

James McDowell

James McDowell was a U.S. Congressman and the 29th Governor of Virginia from 1843 to 1846.McDowell was born at "Cherry Grove," near Rockbridge County, Virginia, on October 13, 1795...

.

Service in the Kentucky General Assembly

Kentucky House of Representatives

The Kentucky House of Representatives is the lower house of the Kentucky General Assembly. It is composed of 100 Representatives elected from single-member districts throughout the Commonwealth. Not more than two counties can be joined to form a House district, except when necessary to preserve...

. Even in his early political career, he began to articulate his stance on the issues that would become his legacy. First, he shunned the states' rights

States' rights

States' rights in U.S. politics refers to political powers reserved for the U.S. state governments rather than the federal government. It is often considered a loaded term because of its use in opposition to federally mandated racial desegregation...

viewpoint, stressing instead the need for a strong interdependence between the states. Second, he called for an end to slavery. Third, he emphasized the importance of education. Though they agreed on this last point, Breckinridge's father had ardently opposed emancipation of slaves and favored states' rights. Historian James Klotter opines that Louis Marshall and Robert's mother, Mary, may have influenced his positions.

The most politically-charged issue in Kentucky during Breckinridge's campaign, however, was the Old Court-New Court controversy

Old Court-New Court controversy

The Old Court – New Court controversy was a 19th century political controversy in the U.S. state of Kentucky in which the Kentucky General Assembly abolished the Kentucky Court of Appeals and replaced it with a new court...

. The Panic of 1819

Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first major financial crisis in the United States, and had occurred during the political calm of the Era of Good Feelings. The new nation previously had faced a depression following the war of independence in the late 1780s and led directly to the establishment of the...

had left many Kentuckians in dire financial straits. Legislators sought to relieve some of the financial burden by passing a law of replevin

Replevin

In creditors' rights law, replevin, sometimes known as "claim and delivery," is a legal remedy for a person to recover goods unlawfully withheld from his or her possession, by means of a special form of legal process in which a court may require a defendant to return specific goods to the...

which favored debtors. The Kentucky Court of Appeals, (the highest court in the Commonwealth at the time,) declared the law unconstitutional. The next year, an incensed General Assembly passed legislation that dissolved the court and replaced it with a new court. Neither court acknowledged the other as valid, and a confused public lost respect for public authority in general. The issue was generally split along party lines, with Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

generally favoring the New Court and Whigs

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

favoring the Old Court.

Breckinridge was able to dodge the issue during the campaign, which he won in 1825, but once he took office, he had to come down on one side or the other. He voted in favor of the Old Court, reflecting his upper class status and affinity for the establishment. In so doing, he identified himself with the party of Kentucky's favorite son, Henry Clay

Henry Clay

Henry Clay, Sr. , was a lawyer, politician and skilled orator who represented Kentucky separately in both the Senate and in the House of Representatives...

. The Whigs would control Kentucky politics for the next twenty-five years. In 1826, the majority of the General Assembly sided with the Old Court and abolished the New Court.

Eventually, tensions faded, but a bigger decision awaited Robert Breckinridge in 1828. He was chosen to sit on a committee that would draft Kentucky's response to the Nullification Crisis

Nullification Crisis

The Nullification Crisis was a sectional crisis during the presidency of Andrew Jackson created by South Carolina's 1832 Ordinance of Nullification. This ordinance declared by the power of the State that the federal Tariff of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and therefore null and void within...

. Because much of South Carolina

South Carolina

South Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

's reasoning for their actions was based on the logic of the Kentucky Resolutions, which were supported by Senator John Breckinridge, Robert Breckinridge now had to determine whether he should support the words of his late father or refute them. In the end, his Unionist sympathies overrode his sense of loyalty to his father; he sided with the committee's majority in condemning South Carolina's actions.

Religious conversion and ministry

Throughout his time in the General Assembly, Breckinridge had battled with typhoid feverTyphoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

. In an 1828 letter to his wife, who was visiting relatives in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, he recounted that he had been bedridden and near death for two months. Finally, in February 1829, the illness subsided. Only then could he be told about the death of his daughter, Louisiana, which had occurred a month earlier. The illness, combined with the news of the death of his daughter, caused Breckinridge turn to religion. In spring 1829, he made a public profession of his faith, and in 1831, he hosted a revival meeting on his farm during which he decided to pursue ministerial training under the West Lexington Presbytery. He was ordained as a Presbyterian minister on April 5, 1832.

Breckinridge served as a Ruling Elder at the Presbyterian General Assembly of 1832, then relocated to Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a community located in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. It is best known as the location of Princeton University, which has been sited in the community since 1756...

to study under Samuel Miller at Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary is a theological seminary of the Presbyterian Church located in the Borough of Princeton, New Jersey in the United States...

. In November 1832, he succeeded his brother John as pastor of Second Presbyterian Church of Baltimore, Maryland. His tenure saw numerous converts, but he was put at odds with his brother and Samuel Miller over practices employed in his church. His counselors were also concerned that he was wavering on his belief in the doctrine of limited atonement

Limited atonement

Limited atonement is a doctrine in Christian theology which is particularly associated with the Reformed tradition and is one of the five points of Calvinism...

. Eventually, he was persuaded back into the doctrines of the orthodox Calvinism

Calvinism

Calvinism is a Protestant theological system and an approach to the Christian life...

and became one of the leaders of the Old School Presbyterian movement.

Now solidly in the Presbyterian fold, Breckinridge began to follow in the footsteps of his brother John, criticizing Roman Catholicism in a number of his speeches and publications. He sponsored and edited two "thoroughly Protestant

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

" journals – the Baltimore Literary and Religious magazine and the Spirit of the XIX Century. A year-long tour of Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

with his wife that began in April 1836 deepened his disdain for the denomination; he opined that most of the continent's ills could be traced back to Catholic "superstitions." A particularly harsh missive against a Catholic who worked in the county almshouse

Almshouse

Almshouses are charitable housing provided to enable people to live in a particular community...

drew an indictment for libel in 1840. The trial ended in a hung jury

Hung jury

A hung jury or deadlocked jury is a jury that cannot, by the required voting threshold, agree upon a verdict after an extended period of deliberation and is unable to change its votes due to severe differences of opinion.- England and Wales :...

that voted 10–2 in favor of acquittal. Though displeased that he could not obtain a unanimous acquittal, Breckinridge continued undaunted. In 1841, he published several of his anti-Catholic articles as Papism in the XIX Century in the United States.

Breckinridge was equally controversial in internal church politics. He rebuked the Synod of the Western Reserve for de-emphasizing and effectively abandoning the office of Ruling Elder. He also condemned the governance of Presbyterian missionaries

Missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group sent into an area to do evangelism or ministries of service, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care and economic development. The word "mission" originates from 1598 when the Jesuits sent members abroad, derived from the Latin...

by anyone other than the Presbyterian church. In 1834, he was the chief author of the Act and Testimony, a document summarizing the contentions between the Old and New Schools. The New School resented Breckinridge and those who signed the Act and Testimony, and even some in the Old School camp had hoped for a more moderate course. The differences between the Old and New Schools widened over the teachings of Albert Barnes, and the New School members were ejected from the Presbyterian Church in 1837. Because of his leadership in the Old School-New School controversy, Breckinridge was rewarded by being elected moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly in 1841.

President of Jefferson College

Pennsylvania

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

in 1845 against the advice of his brothers John and William. A rift between Breckinridge and his brother Cabell's widow and other relatives may help account for this surprising decision. He did not feel he could yet return to his home state.

Breckinridge was inaugurated as president of Jefferson College on September 27, 1845. During his tenure, he also pastored a church in the city of Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

Canonsburg, Pennsylvania

Canonsburg is a borough in Washington County, Pennsylvania, southwest of Pittsburgh. Canonsburg was laid out by Colonel John Canon in 1789 and incorporated in 1802....

. College administration apparently did not suit him, however. A student uprising against the president and the faculty occurred in 1846, hastening the end of his short stay at the school. A desire to see his children, most of whom were living with relatives scattered throughout Kentucky and Virginia, also factored into his decision to resign his post in 1847. On his resignation, he was awarded an honorary

Honorary degree

An honorary degree or a degree honoris causa is an academic degree for which a university has waived the usual requirements, such as matriculation, residence, study, and the passing of examinations...

LL.D from the school.

Father of Kentucky's public school system

Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby was the first and fifth Governor of the U.S. state of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia and North Carolina. He was also a soldier in Lord Dunmore's War, the Revolutionary War, and the War of 1812...

. Their written exchanges included love poems from Robert and concerned questions from Virginia about the wisdom of engaging in a relationship. Despite being advised by her sisters to avoid the marriage and her own open wavering on the issue, the two were married in April 1847. They had three children, only one of whom survived to adulthood. Disagreements among the children of both partners' previous marriages exacerbated an already tense union, which almost ended in divorce in September 1856. Nevertheless, Robert managed to reconcile with his wife, and they remained together until Virginia's death in 1859.

Oddly, Breckinridge's personal turmoil did not hinder his political accomplishments. He was appointed superintendent of public education by Governor William Owsley

William Owsley

William Owsley was an associate justice on the Kentucky Court of Appeals and the 16th Governor of Kentucky. He also served in both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly and was Kentucky Secretary of State under Governor James Turner Morehead.Owsley studied law under John Boyle...

. He was the sixth person to hold the office since its creation in the 1830s. The task was daunting. Only one out of every ten school-age children in Kentucky ever attended school, and at least thirty Kentucky counties had received no state educational funds since 1840.

Breckinridge began reforms immediately and zealously. He secured the General Assembly's passage of a two-cent property tax for education. The tax was subject to voter approval, and Breckinridge worked hard to publicize the issue. His efforts paid off, as the tax passed by almost a two-to-one margin. Continuing to publicize needs and push legislators to action, Breckinridge enjoyed the support of five of the six governors under whom he served. Only John L. Helm

John L. Helm

John LaRue Helm was the 18th and 24th governor of the U.S. state of Kentucky, although his service in that office totaled less than fourteen months. He also represented Hardin County in both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly and was chosen to be the Speaker of the Kentucky House of...

, who opposed a state-funded school system, challenged him, but Helm's veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

of a Breckinridge educational bill was overridden in the General Assembly. Breckinridge's reforms manifested tangible results. From 1847 to 1850, educational spending increased from $6,000 to $144,000. By 1850, only one out of every ten school age children did not attend school.

In 1850, Kentuckians ratified their third constitution

Kentucky Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the document that governs the Commonwealth of Kentucky. It was first adopted in 1792 and has since been rewritten three times and amended many more...

. One of many changes effected by this document was that the office of superintendent became elective. Though the election belonged to the Democrats, Breckinridge, a Whig, was elected over five challengers for the office. His tenure would be a short one, however. Unlike his early reforms, his calls for parental selection of textbooks and use of the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

as the primary reading material were not heeded. He also opposed the abolition of tuition charges and unsuccessfully lobbied for a pay increase for his position. (The salary was only $750.) With little prospect of further reform under his leadership, Breckinridge resigned in 1853.

Following his resignation, Breckinridge's party affiliation progressed from Whig

Whig Party (United States)

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from the early 1830s to the mid-1850s, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic...

to Know-Nothing to Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

. In 1853, helped found Danville Theological Seminary in Danville, Kentucky

Danville, Kentucky

Danville is a city in and the county seat of Boyle County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 16,218 at the 2010 census.Danville is the principal city of the Danville Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Boyle and Lincoln counties....

, becoming a Professor of Exegetic, Didactic and Polemic Theology.

Civil War and later life

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

for president in the election of 1860

United States presidential election, 1860

The United States presidential election of 1860 was a quadrennial election, held on November 6, 1860, for the office of President of the United States and the immediate impetus for the outbreak of the American Civil War. The nation had been divided throughout the 1850s on questions surrounding the...

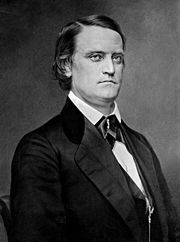

pitted him against his own nephew, Vice President John C. Breckinridge

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Kentucky and was the 14th Vice President of the United States , to date the youngest vice president in U.S...

.

At the outbreak of the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Breckinridge quickly became an ardent supporter of the Union, not for its position against slavery, but for the sake of preserving the Union. He used his position as editor of the Danville Quarterly Review to advocate his position. He called for harsh measures against secession, and in time, accepted President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Lincoln's immediate emancipation of slaves. He was chosen as the temporary chair of the 1864 Republican National Convention

Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention is the presidential nominating convention of the Republican Party of the United States. Convened by the Republican National Committee, the stated purpose of the convocation is to nominate an official candidate in an upcoming U.S...

that re-nominated Lincoln for president, and his pro-Union speech was hailed by freshman Representative

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

James G. Blaine

James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine was a U.S. Representative, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, U.S. Senator from Maine, two-time Secretary of State...

as one of the most inspiring given at the event.

Breckinridge's family split on the issue, with two of his sons – Joseph

Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, Sr.

Joseph Cabell Breckinridge, Sr. was a Major General, but fought for the Union in the American Civil War.Breckinridge was a member of the prominent Breckinridge family at the family's Cabell's Dale estate near Lexington, Kentucky...

and Charles – fighting for the Union cause, and two – Willie

William Campbell Preston Breckinridge

William Campbell Preston Breckinridge was a Democratic U.S. Representative from Kentucky, a Member of the Masonic Lodge, and a Member of the Knights Templar. He was the first cousin of Vice President of the United States John C. Breckinridge.He was born in Baltimore, Maryland, and graduated from...

and Robert Jr.

Robert Jefferson Breckinridge, Jr.

Robert Jefferson Breckinridge, Jr. was a prominent Kentucky politician and a member of the Breckenridge political family. He was the son of Robert Jefferson Breckinridge and brother of William Campbell Preston Breckinridge. He was born in Baltimore, Maryland. He served as a colonel in the...

– fighting for the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

. While three of his sons-in-law also fought for the Union, daughter Sophonisba

Sophonisba Breckinridge

Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge was an American activist, Progressive Era social reformer, social scientist and innovator in higher education.- Background :...

's husband, Theophilus Steele, rode with John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan was a Confederate general and cavalry officer in the American Civil War.Morgan is best known for Morgan's Raid when, in 1863, he and his men rode over 1,000 miles covering a region from Tennessee, up through Kentucky, into Indiana and on to southern Ohio...

, and it is likely that Robert Breckinridge's intervention kept him from being executed by Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton was an American lawyer and politician who served as Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during the American Civil War from 1862–1865...

. Following the war, Willie Breckinridge's wife Issa refused to let her father-in-law see two of his grandchildren for a period of two years.

On November 5, 1868, Breckinridge married his third wife, Margaret Faulkner White. A year later, he resigned his professorship at Danville Seminary. He died on December 27, 1871 after an extensive illness, and was buried in Lexington Cemetery.

Legacy

In 1892, Breckinridge Hall (named for Breckinridge) was built as a dormitory for students of the Danville Theological Seminary. It is now a residence hall for upper-class students at Centre CollegeCentre College

Centre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, USA, a community of approximately 16,000 in Boyle County south of Lexington, KY. Centre is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution. Centre was founded by Presbyterian leaders, with whom it maintains a loose...

in Danville - Breckinridge's nephew John C. Breckinridge

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Kentucky and was the 14th Vice President of the United States , to date the youngest vice president in U.S...

's alma mater. Breckinridge Hall was renovated in 1999, and is on the National Register of Historic Places

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places is the United States government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects deemed worthy of preservation...

. http://www.centre.edu/campusbuildings/slideshow_breck/index.html

Breckinridge Hall, a three-story building on Morehead State University's campus, is named for Robert J. Breckinridge.

Selected works of Robert Breckinridge

- The Knowledge of God, Objectively Considered: Being the First Part of Theology Considered as a Science of Positive Truth, Both Inductive and Deductive

- The Knowledge of God, Subjectively Considered: Being the Second Part of Theology Considered as a Science of Positive Truth, Both Inductive and Deductive

- Our country – its peril and its deliverance.

- Breckinridge's protest against the use of instrumental music in worship

- Presbyterian Government not a Hierarchy, but a Commonwealth

- Presbyterian Ordination not a Charm, but an Act of Government

- Some Thoughts on the Development of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.

- The Christian Pastor, One of Christ's Ascension Gifts

- Letter of Robert J. Breckinridge to the Second Presbyterian Church of Baltimore

- Robert J. Breckinridge's speech at the laying of the cornerstone of the Clay Monument

- The Calling of the Church of Christ: A Discourse to Illustrate the Posture and Duty of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America

Further reading

- Memorial and Biographical Sketches by James Freeman Clarke, 1878

- A Popular History of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America by Jacob Harris Patton, 1900