Ramsay MacDonald

Encyclopedia

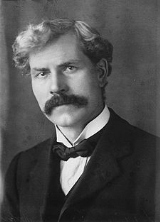

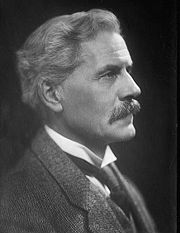

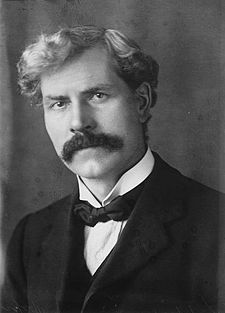

James Ramsay MacDonald, PC

, FRS (12 October 1866 – 9 November 1937) was a British

politician

who was the first ever Labour

Prime Minister

, leading a minority government

for two terms.

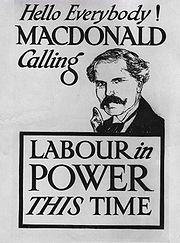

MacDonald entered Parliament at the 1906 General Election

and had become chairman of the Labour MPs by 1914. His opposition to the First World War made him unpopular and he was defeated at the 1918 General Election

, returning to Parliament at the 1922 General Election

, at which Labour replaced the Liberals as the largest left-wing party in the UK. MacDonald was a powerful if woolly orator and by then had earned great public respect for his opposition to the war. His first government - formed with Liberal support - in 1924 lasted nine months, but was defeated at the 1924 General Election

amidst allegations, now thought to have been fabricated, that his government was endorsed by the Soviet Foreign Minister Zinoviev

.

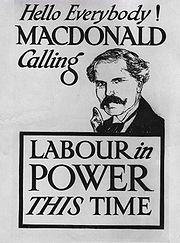

Labour returned to power - this time as the largest party - in 1929

but was soon overwhelmed by the crisis of the Great Depression

, in which the Labour government was split by demands for public spending cuts to preserve the Gold Standard

. In 1931

, he formed a National Government

in which only two of his Labour colleagues agreed to serve and the majority of whose MPs were from the Conservatives

. As a result, MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party, which accused him of "betrayal". The Gold Standard soon had to be abandoned after the Invergordon Mutiny

and MacDonald's National Government won a huge "doctor's mandate" at the 1931 General Election

, at which the Labour Party was reduced to a rump of around 50 seats in the House of Commons.

MacDonald remained Prime Minister of the National Government from 1931 to 1935

; during this time his health rapidly deteriorated and he became increasingly ineffective as a leader. He stood down as Prime Minister in 1935 - losing his seat in the General Election that year

and returning for a different constituency - but stayed in the Cabinet as Lord President of the Council

until retiring from the government in 1937 and dying, still an MP, later that year. For many years his reputation remained low, particularly amongst Labour supporters, although his record is to some extent defended by modern historians.

, Morayshire, Scotland

, the illegitimate son of John Macdonald, a farm labourer, and Anne Ramsay, a housemaid. Although registered at birth as James McDonald Ramsay, he was known as Jaimie MacDonald. Illegitimacy could be a serious handicap in 19th-century Presbyterian Scotland, but in the north and northeast farming communities, this was less of a problem; in 1868 a report of the Royal Commission on the Employment of Children, Young Persons and Women in Agriculture noted that the illegitimacy rate was around 15%.

He received an elementary education at the Free Church of Scotland

school in Lossiemouth, and then from 1875 at the local Drainie parish school. In 1881 he became a pupil teacher at Drainie and the entry in the school register as a member of staff was 'J. MacDonald'. He remained in this post until 1 May 1885 to take up a position as an assistant to a clergyman in Bristol. It was in Bristol, that he joined the Democratic Federation, an extreme Radical

sect. This federation changed its name a few months later to the Social Democratic Federation

(SDF). He remained in the group when it left the SDF to become the Bristol Socialist Society

. MacDonald returned to Lossiemouth before the end of the year for reasons unknown, but in early 1886 once again left for London.

which, unlike the SDF, aimed to progress socialist ideals through the parliamentary system. MacDonald witnessed the Bloody Sunday

MacDonald witnessed the Bloody Sunday

of 13 November 1887 in Trafalgar Square

and in response to this he had a pamphlet published by the Pall Mall Gazette

entitled Remember Trafalgar Square: Tory Terrorism in 1887.

MacDonald retained an interest in Scottish politics. Gladstone

's first Irish Home Rule Bill inspired the setting-up of a Scottish Home Rule Association in Edinburgh

. On 6 March 1888, MacDonald took part in a meeting of Scotsmen who were London residents and who, on his motion, formed the London General Committee of Scottish Home Rule Association. He continued to support home rule for Scotland, but with little support from London Scots forthcoming, his enthusiasm for the committee waned and from 1890 he took little part in its work. However, MacDonald never lost his interest in Scottish politics and home rule, and in his Socialism: critical and constructive, published in 1921, he wrote: "The Anglification of Scotland has been proceeding apace to the damage of its education, its music, its literature, its genius, and the generation that is growing up under this influence is uprooted from its past."

Politics in the 1890s was still of less importance to MacDonald than furthering himself in employment. To this end he took evening classes in science

, botany

, agriculture

, mathematics

, and physics

at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution

but his health suddenly failed him due to exhaustion one week before his examinations. This put an end to any thought of having a career in science. In 1888, MacDonald took employment as private secretary to Thomas Lough

who was a tea merchant and a Radical

politician. Lough was elected as the Liberal

Member of Parliament

(MP) for West Islington

, in 1892. Many doors now opened to MacDonald. He had access to the National Liberal Club

as well as the editorial offices of Liberal and Radical newspapers. He also made himself known to various London Radical clubs and with Radical and labour politicians. MacDonald gained valuable experience in the workings of electioneering. In 1892, he left Lough’s employment to become a journalist and was not immediately successful. By then, MacDonald had been a member of the Fabian Society

for some time and toured and lectured on its behalf at the London School of Economics

and elsewhere.

had created the Labour Electoral Association (LEA) and entered into an unsatisfactory alliance with the Liberal Party in 1886. In 1892, MacDonald was in Dover to give support to the candidate for the LEA in the General Election and who was well beaten. MacDonald impressed the local press and the Association, however, and was adopted as its candidate. MacDonald, though, announced that his candidature would be under a Labour Party banner. He denied that the Labour Party was a wing of the Liberal Party but saw merit in a working relationship. In May 1894, the local Southampton Liberal Association was trying to find a labour minded candidate for the constituency. MacDonald along with two others were invited to address the Liberal Council. One of three men turned down the invitation and MacDonald failed to secure the candidature despite the strong support he had among Liberals.

In 1893, Keir Hardie

In 1893, Keir Hardie

had formed the Independent Labour Party

(ILP) which had established itself as a mass movement and so in May 1894 MacDonald applied for membership of, and was accepted into, the ILP. He was officially adopted as the ILP candidate for one of the Southampton seats on 17 July 1894 but was heavily defeated at the election of 1895. MacDonald stood for Parliament again in 1900 for one of the two Leicester seats and although he lost was accused of splitting the Liberal vote to allow the Conservative candidate to win. That same year he became Secretary of the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), the forerunner of the Labour Party, while retaining his membership of the ILP. The ILP, while not a Marxist

party, was more rigorously socialist than the future Labour Party in which the ILP members would operate as a "ginger group

" for many years.

As Party Secretary, MacDonald negotiated an agreement

with the leading Liberal politician Herbert Gladstone (son of the late Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone

), which allowed Labour to contest a number of working-class seats without Liberal opposition, thus giving Labour its first breakthrough into the House of Commons. He married Margaret Ethel Gladstone

, who was unrelated to the Gladstones of the Liberal Party, in 1896. Margaret MacDonald was very comfortably off, although not hugely wealthy. This allowed them to indulge in foreign travel, visiting Canada and the United States in 1897, South Africa in 1902, Australia and New Zealand in 1906 and to India several times.

It was during this period that MacDonald and his wife began a long friendship with the social investigator and reforming civil servant Clara Collet

with whom he discussed women's issues. She influenced MacDonald and other politicians in their attitudes towards women and especially their work. In 1901, he was elected to the London County Council

for Finsbury Central as a joint Labour-Progressive Party

candidate, but he was disqualified from the register in 1904 due to his absences abroad.

In 1906, the LRC changed its name to the "Labour Party

", and absorbed the ILP. In that same year, MacDonald was elected MP for Leicester

along with 28 others, and became one of the leaders of the Parliamentary Labour Party

. These Labour MPs undoubtedly owed their election to the ‘Progressive Alliance’ between the Liberals and Labour which at this time was a minor party supporting the Liberal governments of Henry Campbell-Bannerman

and Herbert Henry Asquith

. MacDonald became the leader of the left wing of the party, arguing that Labour must seek to displace the Liberals as the main party of the left.

Up to 1910 his name was usually styled Ramsay Macdonald, thereafter Ramsay MacDonald.

In 1911 MacDonald became Party Leader (formally "Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party"), but within a short period his wife became ill with blood poisoning and died. This affected MacDonald greatly. MacDonald had always taken a keen interest in foreign affairs and knew from his visit to South Africa just after the Boer War

In 1911 MacDonald became Party Leader (formally "Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party"), but within a short period his wife became ill with blood poisoning and died. This affected MacDonald greatly. MacDonald had always taken a keen interest in foreign affairs and knew from his visit to South Africa just after the Boer War

had ended, what the effects of modern conflict would have. Although the Parliamentary Labour Party generally held an anti-war opinion, when war was declared in August 1914, patriotism came to the fore. Labour supported the government in its request for £100,000,000 of war credits and, as MacDonald could not support this, he resigned the Chairmanship. Arthur Henderson

became the new leader while MacDonald took the party Treasurer post. During the early part of the war he was extremely unpopular and was accused of treason and cowardice. Horatio Bottomley

attacked him through his magazine John Bull

in September 1915 by publishing an article carrying details of MacDonald's birth and his so-called deceit in not disclosing his real name. His illegitimacy was no secret and he hadn’t seemed to have suffered by it, but according to the journal he had, by using a false name, gained access to parliament falsely, and should suffer heavy penalties and have his election declared void. MacDonald received much support but the way in which the disclosures were made public had affected him. He wrote in his diary:

Despite his opposition to the war, MacDonald still visited the front in December 1914. Lord Elton

wrote:

As the war dragged on his reputation recovered but nevertheless he lost his seat in the 1918 "Coupon Election

As the war dragged on his reputation recovered but nevertheless he lost his seat in the 1918 "Coupon Election

", which saw the Liberal David Lloyd George

coalition government win a huge majority.

MacDonald stood for Parliament in the 1921 Woolwich East by-election

, and lost to war veteran and Victoria Cross

winner Robert Gee

. In 1922 the Conservatives left the coalition and Bonar Law, who had taken over from Lloyd George, called an election on 26 October. MacDonald was returned to the House as MP for Aberavon

in Wales and his rehabilitation was complete; the Labour New Leader wrote that his election was

, making MacDonald Leader of the Opposition. By this time he had moved away from the Labour left and abandoned the socialism of his youth — he strongly opposed the wave of radicalism that swept through the labour movement in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917

— and became a determined enemy of Communism

. Unlike the French Socialist Party and the German SPD

, the Labour Party did not split and the Communist Party of Great Britain

remained small and isolated.

Although he was a gifted speaker, MacDonald became noted for 'woolly' rhetoric such as the occasion at the Labour Party Conference of 1930 at Llandudno when he appeared to imply unemployment could be solved by encouraging the jobless to return to the fields "where they till and they grow and they sow and they harvest". Equally there were times it was unclear what his policies were. There was already some unease in the party about what he would do if Labour was able to form a government. At the 1923 election the Conservatives lost their majority, and when they lost a vote of confidence in the House in January 1924 King George V

called on MacDonald to form a minority Labour government, with the tacit support of the Liberals under Asquith from the corner benches. MacDonald thus became the first Labour Prime Minister, the first from a working-class background and one of the very few without a university education.

in January 1924 and made it clear that his main priority was to undo the damage which he believed had been caused by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles

, by settling the reparations

issue and coming to terms with Germany. He left domestic matters to his ministers, including J.R. Clynes

as Lord Privy Seal

, Philip Snowden as Chancellor of the Exchequer

and Henderson as Home Secretary

. King George V

noted in his diary that "He wishes to do the right thing...Today 23 years ago dear Grandmama died. I wonder what she would have thought of a Labour Government!"

The Government was only to last nine months and did not have a majority in either House of the Parliament, nevertheless it was still able to support the unemployed with the extension of benefits and amendments to the Insurance Acts. In a personal triumph for John Wheatley

, Minister for Health, a Housing Act was passed which greatly expanded municipal housing for low paid workers.

MacDonald took the decision in March 1924 to end construction work on the Singapore

military base despite strong opposition from the Admiralty. MacDonald believed the building of the base would endanger the disarmament conference; the First Sea Lord

Lord Beatty

considered the absence of such a base as dangerously imperilling British trade and territories east of Aden

, and would mean the security of the British Empire in the Far East being dependent on the goodwill of Japan

.

In June, MacDonald convened a conference in London of the wartime Allies, and achieved an agreement on a new plan for settling the reparations issue and the French occupation of the Ruhr

. German delegates then joined the meeting, and the London Settlement was signed. This was followed by an Anglo-German commercial treaty. Another major triumph for MacDonald was the conference held in London in July–August 1924 to deal with the implementation of the Dawes Plan

. MacDonald, who accepted the view of the economist John Maynard Keynes

of German reparations

as impossible to pay successfully pressured the French Premier Édouard Herriot

into a whole series of concessions to Germany. A British onlooker commented that “The London Conference was for the French 'man in the street' one long Calvary...as he saw M. Herriot abandoning one by one the cherished possessions of French preponderance on the Reparations Commission, the right of sanctions in the event of German default, the economic occupation of the Ruhr, the French-Belgian railroad Régie, and finally, the military occupation of the Ruhr within a year.” MacDonald was hugely proud of what had been achieved; this was the pinnacle of his short-lived administration's achievements. In September he made a speech to the League of Nations

Assembly in Geneva

, the main thrust of which was for general European disarmament

which was received with great acclamation.

But before all of this the United Kingdom had recognised the Soviet Union and MacDonald informed parliament in February 1924 that negotiations would begin to negotiate a treaty with the Soviet Union. The treaty was to cover Anglo-Soviet trade and the situation of the British bondholders who had contracted with the pre-revolutionary Russian government and which had been rejected by the Bolsheviks. There were in fact to be two treaties. One covering commercial matters and the other to cover a fairly vague future discussion on the problem of the bondholders. If and when the treaties were signed, then the British government would conclude a further treaty and guarantee a loan to the Bolsheviks. The treaties were popular neither with the Conservatives nor with the Liberals who, in September, criticised the loan so vehemently that negotiation with them seemed impossible.

However, it was the "Campbell Case

" — the abrogation of prosecuting the left-wing newspaper

the Workers Weekly — that determined its fate. The Conservatives put forth a censure motion, to which the Liberals added an amendment. MacDonald's Cabinet resolved to treat both motions as matters of confidence, which if passed, would necessitate a dissolution of government. The Liberal amendment carried and the King granted MacDonald a dissolution of parliament the following day. The issues which dominated the election campaign were, unsurprisingly, the Campbell case and the Russian treaties which soon combined into the single issue of the Bolshevik threat.

reported that a letter had come into its possession which purported to be a letter sent from Grigory Zinoviev

, the President of the Communist International, to the British representative on the Comintern Executive. The letter was dated 15 September and so before the dissolution of parliament; it stated that it was imperative that the agreed treaties between Britain and the Bolsheviks be ratified urgently. To this end, the letter said that those Labour members who could apply pressure on the government should do so. It went on to say that a resolution of the relationship between the two countries would "assist in the revolutionising of the international and British proletariat .... make it possible for us to extend and develop the ideas of Leninism in England and the Colonies." The government had received the letter before the publication in the newspapers and had protested to the Bolshevik’s London chargé d'affaires and had already decided to make public the contents of the letter together with details of the official protest but had not been swift footed enough. MacDonald always believed that the letter was forgery but damage had been done to his campaign.

Despite all that had gone on, the result of the election was not disastrous to Labour. The Conservatives were returned decisively gaining 155 seats for a total of 413 members of parliament. Labour lost 40 seats but held on to 151. The Liberals lost 118 seats (leaving them with only 40) and their vote fell by over a million. The real significance of the election was that the Liberals - whom Labour had displaced as the second largest political party in 1922 - were now clearly a minor party.

and miners’ strike of 1926. Unemployment in the UK during this period remained high but relatively stable at just over 10% and, apart from 1926, strikes were at a low level. At the May 1929 election

, Labour won 288 seats to the Conservatives' 260, with 59 Liberals under Lloyd George holding the balance of power. At this election, MacDonald moved from Aberavon to the seat of Seaham Harbour

in County Durham

. Baldwin resigned and MacDonald again formed a minority government, at first with Lloyd George's cordial support.

This time MacDonald knew he had to concentrate on domestic matters. Arthur Henderson

This time MacDonald knew he had to concentrate on domestic matters. Arthur Henderson

became Foreign Secretary, with Snowden again at the Exchequer. JH Thomas

became Lord Privy Seal with a mandate to tackle unemployment, assisted by the young radical Oswald Mosley

. MacDonald appointed the first ever woman cabinet minister Margaret Bondfield

as Minister of Labour

.

MacDonald's second government was in a stronger parliamentary position than his first, and in 1930 he was able to raise unemployment pay, pass an act to improve wages and conditions in the coal industry (i.e. the issues behind the General Strike) and pass a housing act which focused on slum clearances. However, an attempt by the Education Minister Charles Trevelyan

to introduce an act to raise the school-leaving age to 15 was defeated by opposition from Roman Catholic Labour MPs, who feared that the costs would lead to increasing local authority control over faith schools.

In international affairs, he also convened a conference in London with the leaders of the Indian National Congress

, at which he offered responsible government

, but not independence, to India. In April 1930 he negotiated a treaty limiting naval armaments with the United States and Japan.

, David Lloyd George

and the economist John Maynard Keynes

. Mosley put forward a memorandum in January 1930, calling for the public control of imports and banking as well as an increase in pensions to boost spending power. When this was repeatedly turned down, Mosley resigned from the government in February 1931 and formed the New Party. He later converted to Fascism

.

By the end of 1930, unemployment had doubled to over two and a half million. The government struggled to cope with the crisis and found itself attempting to reconcile two contradictory aims: achieving a balanced budget in order to maintain the pound

on the Gold standard

, and maintaining assistance to the poor and unemployed, at a time when tax revenues were falling. During 1931 the economic situation deteriorated, and pressure from orthodox economists for sharp cuts in government spending increased. Under pressure from its Liberal allies as well as the Conservative opposition who feared that the budget was unbalanced. Snowden appointed a committee headed by Sir George May

to review the state of public finances. The May Report

of July 1931 urged large public-sector wage cuts and large cuts in public spending (notably in payments to the unemployed) in order to avoid a budget deficit.

Keynes urged MacDonald to devalue the pound by 25% and abandon the existing economic policy of a balanced budget. MacDonald, Snowden, and Thomas supported such measures as necessary to maintain a balanced budget and to prevent a run on the pound, but the proposed cuts split the Cabinet down the middle and the trade unions bitterly opposed them.

who made it clear they would resign rather than acquiesce to the cuts. With this unworkable split, on 24 August 1931 MacDonald submitted his resignation and then agreed, on the urging of King George V

to form a National Government with the Conservatives and Liberals. MacDonald, Snowden, and Thomas were quickly expelled from the Labour Party and subsequently formed a new National Labour group, which received little support in the country or the unions. Great anger in the labour movement greeted MacDonald's move. Mass riots by unemployed people took place in protest in Glasgow

and Manchester

. Many in the Labour Party viewed this as a cynical move by MacDonald to rescue his career, and accused him of 'betrayal'. MacDonald, however, argued that the sacrifice was for the common good.

The National Government won 554 seats, comprising 470 Conservatives, 13 National Labour, 68 Liberals (Liberal National and Liberal) and various others, while Labour, now led by Arthur Henderson won only 52 and the Lloyd George Liberals four. Henderson and his deputy J. R. Clynes both lost their seats in Labour's worst-ever rout. Labour's disastrous performance at the 1931 election greatly increased the bitterness felt by MacDonald's former colleagues towards him. MacDonald was genuinely upset to see the Labour Party so badly defeated at the election. He had regarded the National Government as a temporary measure, and had hoped to return to the Labour Party.

and Neville Chamberlain

who between them effectively controlled domestic policy.

With little influence at home, MacDonald involved himself heavily in foreign policy. Assisted by the National Liberal

leader and Foreign Secretary John Simon

, he continued to lead important British delegations, including the Geneva Disarmament Conference and the Lausanne Conference in 1932, and the Stresa Conference in 1935.

MacDonald was deeply affected by the anger and bitterness caused by the fall of the Labour government. He continued to regard himself as a true Labour man, but the rupturing of virtually all his old friendships left him an isolated figure. Phillip Snowden, a firm believer in free trade

, resigned from the government in 1932 following the introduction of tariffs after the Ottawa agreement. This robbed MacDonald of his only significant political ally.

and others to accuse him of failure to stand up to the threat of Adolf Hitler

. MacDonald was aware of his fading powers, and in 1935 he agreed a timetable with Baldwin to stand down as Prime Minister after George V

's Silver Jubilee

celebrations in May 1935. He resigned on 7 June in favour of Baldwin, and remained in the cabinet, taking the largely honorary post of Lord President

vacated by Baldwin.

later in the year MacDonald was defeated at Seaham by Emanuel Shinwell. Shortly after he was elected at a by-election in January 1936

for the Combined Scottish Universities seat, but his physical and mental health collapsed in 1936. A sea voyage was recommended to restore his health, but he died on board the liner Reina del Pacifico

at sea on 9 November 1937, aged 71. He was buried alongside his wife at Spynie in his native Morayshire.

in his autobiography As it Happened (1954) called MacDonald's decision to abandon the Labour government in 1931 "the greatest betrayal in the political history of the country".

It was not until 1977 that he received a supportive biography, when Professor David Marquand

, a former Labour MP, wrote Ramsay MacDonald with the stated intention of giving MacDonald his due for his work in founding and building the Labour Party, and in trying to preserve peace in the years between the two world wars. He argued also to place MacDonald's fateful decision in 1931 in the context of the crisis of the times and the limited choices open to him.

Similarly, opinion about the economic decisions taken in the inter-war period (Winston Churchill

's decision to return to the Gold Standard in 1925, and MacDonald's desperate efforts to defend it in 1931) is no longer as uniformly hostile as was once the case. Robert Skidelsky, in his classic account of the 1929–31 government, Politicians and the Slump (1967), compared the orthodox policies advocated by leading politicians of both parties unfavourably with the more radical, proto-Keynesian measures advocated by David Lloyd George

and Oswald Mosley

. But in the preface to the 1994 edition Skidelsky argues that recent experience of currency crises and capital flight make it hard to be critical of politicians who wanted to achieve stability by cutting labour costs and defend the value of the currency.

's 1940 novel Fame is the Spur, later made into a 1947 film

and a 1982 TV adaptation

, the lead character Hamer Shawcross is generally believed to be based upon Ramsay MacDonald.

In the twenty-fourth episode of Monty Python's Flying Circus

, original footage of Ramsay McDonald entering No. 10 Downing Street is followed by a black and white film of McDonald (played by Michael Palin) doing a striptease, revealing garter belt, suspender and stockings.

In Graham Greene

's 1934 novel It's a Battlefield

, Ramsay McDonald's name repeatedly appears in Newspapers and on billboards in reference to a visit to Lossiemouth. He is also mentioned and featured in Noel Coward's film, "This Happy Breed".

(1901–81), who had a prominent career as a politician, colonial governor and diplomat, and Ishbel MacDonald

(1903–82), who was very close to her father. Another son, Alister Gladstone MacDonald (1898–1993) was a prominent architect who worked on promoting the planning policies of his father's government, and specialised in cinema design. MacDonald was devastated by Margaret's death from blood poisoning in 1911, and had few significant personal relationships after that time, apart from with Ishbel, who cared for him for the rest of his life. Following his wife's death, MacDonald commenced a relationship with Lady Margaret Sackville

.

In the 1920s and 1930s he was frequently entertained by the society hostess Lady Londonderry

, which was much disapproved of in the Labour Party since her husband was a Conservative cabinet minister.

MacDonald's unpopularity in the country following his stance against Britain's involvement in the First World War spilled over into his private life. In 1916, he was expelled from the Moray Golf Club in Lossiemouth

for supposedly bringing the club into disrepute because of his pacifist views. The manner of his expulsion was regretted by some members but an attempt to re-instate him by a vote in 1924 failed. However a Special General Meeting held in 1929 finally voted for his reinstatement. By this time, MacDonald was Prime Minister for the second time. He felt the initial expulsion very deeply and refused to take up the final offer of membership.

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

, FRS (12 October 1866 – 9 November 1937) was a British

British people

The British are citizens of the United Kingdom, of the Isle of Man, any of the Channel Islands, or of any of the British overseas territories, and their descendants...

politician

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

who was the first ever Labour

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

, leading a minority government

Minority government

A minority government or a minority cabinet is a cabinet of a parliamentary system formed when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in the parliament but is sworn into government to break a Hung Parliament election result. It is also known as a...

for two terms.

MacDonald entered Parliament at the 1906 General Election

United Kingdom general election, 1906

-Seats summary:-See also:*MPs elected in the United Kingdom general election, 1906*The Parliamentary Franchise in the United Kingdom 1885-1918-External links:***-References:*F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987**...

and had become chairman of the Labour MPs by 1914. His opposition to the First World War made him unpopular and he was defeated at the 1918 General Election

United Kingdom general election, 1918

The United Kingdom general election of 1918 was the first to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918, which meant it was the first United Kingdom general election in which nearly all adult men and some women could vote. Polling was held on 14 December 1918, although the count did...

, returning to Parliament at the 1922 General Election

United Kingdom general election, 1922

The United Kingdom general election of 1922 was held on 15 November 1922. It was the first election held after most of the Irish counties left the United Kingdom to form the Irish Free State, and was won by Andrew Bonar Law's Conservatives, who gained an overall majority over Labour, led by John...

, at which Labour replaced the Liberals as the largest left-wing party in the UK. MacDonald was a powerful if woolly orator and by then had earned great public respect for his opposition to the war. His first government - formed with Liberal support - in 1924 lasted nine months, but was defeated at the 1924 General Election

United Kingdom general election, 1924

- Seats summary :- References :* F. W. S. Craig, British Electoral Facts: 1832-1987* - External links :* * *...

amidst allegations, now thought to have been fabricated, that his government was endorsed by the Soviet Foreign Minister Zinoviev

Zinoviev Letter

The "Zinoviev Letter" refers to a controversial document published by the British press in 1924, allegedly sent from the Communist International in Moscow to the Communist Party of Great Britain...

.

Labour returned to power - this time as the largest party - in 1929

1929 in the United Kingdom

Events from the year 1929 in the United Kingdom.-Incumbents:*Monarch - King George V*Prime Minister - Stanley Baldwin, Conservative , Ramsay MacDonald, Labour-Events:...

but was soon overwhelmed by the crisis of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

, in which the Labour government was split by demands for public spending cuts to preserve the Gold Standard

Gold standard

The gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is a fixed mass of gold. There are distinct kinds of gold standard...

. In 1931

1931 in the United Kingdom

Events from the year 1931 in the United Kingdom.-Incumbents:*Monarch - King George V*Prime Minister - Ramsay MacDonald, Labour and national coalition-Events:* 6 January - Sadler's Wells Theatre opens in London....

, he formed a National Government

UK National Government

In the United Kingdom the term National Government is an abstract concept referring to a coalition of some or all major political parties. In a historical sense it usually refers primarily to the governments of Ramsay MacDonald, Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain which held office from 1931...

in which only two of his Labour colleagues agreed to serve and the majority of whose MPs were from the Conservatives

Conservative Party (UK)

The Conservative Party, formally the Conservative and Unionist Party, is a centre-right political party in the United Kingdom that adheres to the philosophies of conservatism and British unionism. It is the largest political party in the UK, and is currently the largest single party in the House...

. As a result, MacDonald was expelled from the Labour Party, which accused him of "betrayal". The Gold Standard soon had to be abandoned after the Invergordon Mutiny

Invergordon Mutiny

The Invergordon Mutiny was an industrial action by around 1,000 sailors in the British Atlantic Fleet, that took place on 15–16 September 1931...

and MacDonald's National Government won a huge "doctor's mandate" at the 1931 General Election

United Kingdom general election, 1931

The United Kingdom general election on Tuesday 27 October 1931 was the last in the United Kingdom not held on a Thursday. It was also the last election, and the only one under universal suffrage, where one party received an absolute majority of the votes cast.The 1931 general election was the...

, at which the Labour Party was reduced to a rump of around 50 seats in the House of Commons.

MacDonald remained Prime Minister of the National Government from 1931 to 1935

1935 in the United Kingdom

Events from the year 1935 in the United Kingdom. This royal Silver Jubilee year sees a General Election and changes in the leadership of both the Conservative and Labour parties.-Incumbents:*Monarch - King George V...

; during this time his health rapidly deteriorated and he became increasingly ineffective as a leader. He stood down as Prime Minister in 1935 - losing his seat in the General Election that year

United Kingdom general election, 1935

The United Kingdom general election held on 14 November 1935 resulted in a large, though reduced, majority for the National Government now led by Conservative Stanley Baldwin. The greatest number of MPs, as before, were Conservative, while the National Liberal vote held steady...

and returning for a different constituency - but stayed in the Cabinet as Lord President of the Council

Lord President of the Council

The Lord President of the Council is the fourth of the Great Officers of State of the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord High Treasurer and above the Lord Privy Seal. The Lord President usually attends each meeting of the Privy Council, presenting business for the monarch's approval...

until retiring from the government in 1937 and dying, still an MP, later that year. For many years his reputation remained low, particularly amongst Labour supporters, although his record is to some extent defended by modern historians.

Lossiemouth

MacDonald was born in LossiemouthLossiemouth

Lossiemouth is a town in Moray, Scotland. Originally the port belonging to Elgin, it became an important fishing town. Although there has been over a 1,000 years of settlement in the area, the present day town was formed over the past 250 years and consists of four separate communities that...

, Morayshire, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, the illegitimate son of John Macdonald, a farm labourer, and Anne Ramsay, a housemaid. Although registered at birth as James McDonald Ramsay, he was known as Jaimie MacDonald. Illegitimacy could be a serious handicap in 19th-century Presbyterian Scotland, but in the north and northeast farming communities, this was less of a problem; in 1868 a report of the Royal Commission on the Employment of Children, Young Persons and Women in Agriculture noted that the illegitimacy rate was around 15%.

He received an elementary education at the Free Church of Scotland

Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900)

The Free Church of Scotland is a Scottish denomination which was formed in 1843 by a large withdrawal from the established Church of Scotland in a schism known as the "Disruption of 1843"...

school in Lossiemouth, and then from 1875 at the local Drainie parish school. In 1881 he became a pupil teacher at Drainie and the entry in the school register as a member of staff was 'J. MacDonald'. He remained in this post until 1 May 1885 to take up a position as an assistant to a clergyman in Bristol. It was in Bristol, that he joined the Democratic Federation, an extreme Radical

Radicals (UK)

The Radicals were a parliamentary political grouping in the United Kingdom in the early to mid 19th century, who drew on earlier ideas of radicalism and helped to transform the Whigs into the Liberal Party.-Background:...

sect. This federation changed its name a few months later to the Social Democratic Federation

Social Democratic Federation

The Social Democratic Federation was established as Britain's first organised socialist political party by H. M. Hyndman, and had its first meeting on June 7, 1881. Those joining the SDF included William Morris, George Lansbury and Eleanor Marx. However, Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx's long-term...

(SDF). He remained in the group when it left the SDF to become the Bristol Socialist Society

Bristol Socialist Society

The Bristol Socialist Society was a political organisation in South West England.The group originated in 1885 as a local affiliate of the Social Democratic Federation. However, in 1886, it instead affiliated to the Socialist Union...

. MacDonald returned to Lossiemouth before the end of the year for reasons unknown, but in early 1886 once again left for London.

London

MacDonald arrived in London jobless but after some short-term menial work, he found employment as an invoice clerk. Meanwhile, MacDonald was deepening his socialist credentials. He engaged himself energetically in C. L. Fitzgerald's Socialist UnionSocialist Union (UK)

The Socialist Union was a British political party active from February 1886 to 1888.The group was formed by socialists around C. L. Fitzgerald who left the Social Democratic Federation in protest at SDF leader H. M. Hyndman's acceptance of money which Maltman Barry had obtained from the...

which, unlike the SDF, aimed to progress socialist ideals through the parliamentary system.

Bloody Sunday (1887)

Bloody Sunday, London, 13 November 1887, was the name given to a demonstration against coercion in Ireland and to demand the release from prison of MP William O'Brien, who was imprisoned for incitement as a result of an incident in the Irish Land War. The demonstration was organized by the Social...

of 13 November 1887 in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square is a public space and tourist attraction in central London, England, United Kingdom. At its centre is Nelson's Column, which is guarded by four lion statues at its base. There are a number of statues and sculptures in the square, with one plinth displaying changing pieces of...

and in response to this he had a pamphlet published by the Pall Mall Gazette

Pall Mall Gazette

The Pall Mall Gazette was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood...

entitled Remember Trafalgar Square: Tory Terrorism in 1887.

MacDonald retained an interest in Scottish politics. Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

's first Irish Home Rule Bill inspired the setting-up of a Scottish Home Rule Association in Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

. On 6 March 1888, MacDonald took part in a meeting of Scotsmen who were London residents and who, on his motion, formed the London General Committee of Scottish Home Rule Association. He continued to support home rule for Scotland, but with little support from London Scots forthcoming, his enthusiasm for the committee waned and from 1890 he took little part in its work. However, MacDonald never lost his interest in Scottish politics and home rule, and in his Socialism: critical and constructive, published in 1921, he wrote: "The Anglification of Scotland has been proceeding apace to the damage of its education, its music, its literature, its genius, and the generation that is growing up under this influence is uprooted from its past."

Politics in the 1890s was still of less importance to MacDonald than furthering himself in employment. To this end he took evening classes in science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

, botany

Botany

Botany, plant science, or plant biology is a branch of biology that involves the scientific study of plant life. Traditionally, botany also included the study of fungi, algae and viruses...

, agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

, mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

, and physics

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution

Birkbeck, University of London

Birkbeck, University of London is a public research university located in London, United Kingdom and a constituent college of the federal University of London. It offers many Master's and Bachelor's degree programmes that can be studied either part-time or full-time, though nearly all teaching is...

but his health suddenly failed him due to exhaustion one week before his examinations. This put an end to any thought of having a career in science. In 1888, MacDonald took employment as private secretary to Thomas Lough

Thomas Lough

Thomas Lough was a British Liberal politician.He was born in Ireland to Matthew Lough and Martha Steel of Cavan, and was educated at the Royal School Cavan and at Wesleyan Connexional School, Dublin....

who was a tea merchant and a Radical

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

politician. Lough was elected as the Liberal

Liberal Party (UK)

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties of the United Kingdom during the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was a third party of negligible importance throughout the latter half of the 20th Century, before merging with the Social Democratic Party in 1988 to form the present day...

Member of Parliament

Member of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

(MP) for West Islington

Islington West (UK Parliament constituency)

Islington West was a borough constituency in the Metropolitan Borough of Islington, in North London.It returned one Member of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1885 until it was abolished for the 1950 general election...

, in 1892. Many doors now opened to MacDonald. He had access to the National Liberal Club

National Liberal Club

The National Liberal Club, known to its members as the NLC, is a London gentlemen's club, now also open to women, which was established by William Ewart Gladstone in 1882 for the purpose of providing club facilities for Liberal Party campaigners among the newly-enlarged electorate after the Third...

as well as the editorial offices of Liberal and Radical newspapers. He also made himself known to various London Radical clubs and with Radical and labour politicians. MacDonald gained valuable experience in the workings of electioneering. In 1892, he left Lough’s employment to become a journalist and was not immediately successful. By then, MacDonald had been a member of the Fabian Society

Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist movement, whose purpose is to advance the principles of democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist, rather than revolutionary, means. It is best known for its initial ground-breaking work beginning late in the 19th century and continuing up to World...

for some time and toured and lectured on its behalf at the London School of Economics

London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science is a public research university specialised in the social sciences located in London, United Kingdom, and a constituent college of the federal University of London...

and elsewhere.

Active politics

The TUCTrades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in the United Kingdom, representing the majority of trade unions...

had created the Labour Electoral Association (LEA) and entered into an unsatisfactory alliance with the Liberal Party in 1886. In 1892, MacDonald was in Dover to give support to the candidate for the LEA in the General Election and who was well beaten. MacDonald impressed the local press and the Association, however, and was adopted as its candidate. MacDonald, though, announced that his candidature would be under a Labour Party banner. He denied that the Labour Party was a wing of the Liberal Party but saw merit in a working relationship. In May 1894, the local Southampton Liberal Association was trying to find a labour minded candidate for the constituency. MacDonald along with two others were invited to address the Liberal Council. One of three men turned down the invitation and MacDonald failed to secure the candidature despite the strong support he had among Liberals.

Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie, Sr. , was a Scottish socialist and labour leader, and was the first Independent Labour Member of Parliament elected to the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

had formed the Independent Labour Party

Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party was a socialist political party in Britain established in 1893. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 to 1932, when it voted to leave...

(ILP) which had established itself as a mass movement and so in May 1894 MacDonald applied for membership of, and was accepted into, the ILP. He was officially adopted as the ILP candidate for one of the Southampton seats on 17 July 1894 but was heavily defeated at the election of 1895. MacDonald stood for Parliament again in 1900 for one of the two Leicester seats and although he lost was accused of splitting the Liberal vote to allow the Conservative candidate to win. That same year he became Secretary of the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), the forerunner of the Labour Party, while retaining his membership of the ILP. The ILP, while not a Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

party, was more rigorously socialist than the future Labour Party in which the ILP members would operate as a "ginger group

Ginger group

A ginger group is a formal or informal group within, for example, a political party seeking to inspire the rest with its own enthusiasm and activity....

" for many years.

As Party Secretary, MacDonald negotiated an agreement

Gladstone-MacDonald pact

The Gladstone-MacDonald pact of 1903 was a secret informal electoral agreement negotiated by Herbet Gladstone, Liberal Party Chief Whip, and Ramsay MacDonald, Secretary of the Labour Representation Committee...

with the leading Liberal politician Herbert Gladstone (son of the late Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times , more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time...

), which allowed Labour to contest a number of working-class seats without Liberal opposition, thus giving Labour its first breakthrough into the House of Commons. He married Margaret Ethel Gladstone

Margaret MacDonald (spouse)

Margaret MacDonald, née Margaret Ethel Gladstone was a feminist, social reformer, and the wife of British politician and future Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Ramsay MacDonald from 1896 until her death from blood poisoning in 1911...

, who was unrelated to the Gladstones of the Liberal Party, in 1896. Margaret MacDonald was very comfortably off, although not hugely wealthy. This allowed them to indulge in foreign travel, visiting Canada and the United States in 1897, South Africa in 1902, Australia and New Zealand in 1906 and to India several times.

It was during this period that MacDonald and his wife began a long friendship with the social investigator and reforming civil servant Clara Collet

Clara Collet

Clara Collet was pivotal in effecting many reforms which greatly improved working conditions and pay for women during the early part of the twentieth century...

with whom he discussed women's issues. She influenced MacDonald and other politicians in their attitudes towards women and especially their work. In 1901, he was elected to the London County Council

London County Council

London County Council was the principal local government body for the County of London, throughout its 1889–1965 existence, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today known as Inner London and was replaced by the Greater London Council...

for Finsbury Central as a joint Labour-Progressive Party

Progressive Party (London)

The Progressive Party was a political party based around the Liberal Party that contested municipal elections in the County of London.It was founded in 1888 by a group of Liberals and leaders of the labour movement. It was also supported by the Fabian Society, and Sidney Webb was one of its...

candidate, but he was disqualified from the register in 1904 due to his absences abroad.

In 1906, the LRC changed its name to the "Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

", and absorbed the ILP. In that same year, MacDonald was elected MP for Leicester

Leicester

Leicester is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England, and the county town of Leicestershire. The city lies on the River Soar and at the edge of the National Forest...

along with 28 others, and became one of the leaders of the Parliamentary Labour Party

Parliamentary Labour Party

In UK politics, the Parliamentary Labour Party is the parliamentary party of the Labour Party in Parliament: Labour MPs as a collective body....

. These Labour MPs undoubtedly owed their election to the ‘Progressive Alliance’ between the Liberals and Labour which at this time was a minor party supporting the Liberal governments of Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman GCB was a British Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and Leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1908. He also served as Secretary of State for War twice, in the Cabinets of Gladstone and Rosebery...

and Herbert Henry Asquith

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, PC, KC served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916...

. MacDonald became the leader of the left wing of the party, arguing that Labour must seek to displace the Liberals as the main party of the left.

Up to 1910 his name was usually styled Ramsay Macdonald, thereafter Ramsay MacDonald.

Party leader

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

had ended, what the effects of modern conflict would have. Although the Parliamentary Labour Party generally held an anti-war opinion, when war was declared in August 1914, patriotism came to the fore. Labour supported the government in its request for £100,000,000 of war credits and, as MacDonald could not support this, he resigned the Chairmanship. Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and he served three short terms as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1908–1910, 1914–1917 and 1931-1932....

became the new leader while MacDonald took the party Treasurer post. During the early part of the war he was extremely unpopular and was accused of treason and cowardice. Horatio Bottomley

Horatio Bottomley

Horatio William Bottomley was a British financier, swindler, journalist, newspaper proprietor, populist politician and Member of Parliament .-Early life:...

attacked him through his magazine John Bull

John Bull (magazine)

John Bull Magazine was a weekly periodical established in the City, London EC4, by Theodore Hook in 1820.-Publication dates:It was a popular periodical that continued in production through 1824 and at least until 1957...

in September 1915 by publishing an article carrying details of MacDonald's birth and his so-called deceit in not disclosing his real name. His illegitimacy was no secret and he hadn’t seemed to have suffered by it, but according to the journal he had, by using a false name, gained access to parliament falsely, and should suffer heavy penalties and have his election declared void. MacDonald received much support but the way in which the disclosures were made public had affected him. He wrote in his diary:

"... I spent hours of terrible mental pain. Letters of sympathy began to pour in upon me... Never before did I know that I had been registered under the name of Ramsay, and cannot understand it now. From my earliest years my name has been entered in lists, like the school register, etc. as MacDonald."

Despite his opposition to the war, MacDonald still visited the front in December 1914. Lord Elton

Godfrey Elton, 1st Baron Elton

Godfrey Elton, 1st Baron Elton , was a British historian.-Early life:Elton was the eldest son of Edward Fiennes Elton and his wife Violet Hylda Fletcher. He was educated at Rugby and Balliol College, Oxford. At Oxford he at first studies classics but later turned to history...

wrote:

"... he arrived in Belgium with an ambulance unit organised by Dr Hector Munro. The following day he had disappeared and agitated enquiry disclosed that he had been arrested and sent back to Britain. At home he saw Lord KitchenerHerbert Kitchener, 1st Earl KitchenerField Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, ADC, PC , was an Irish-born British Field Marshal and proconsul who won fame for his imperial campaigns and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War, although he died halfway...

who expressed his annoyance at the incident and gave instructions for him to be given an 'omnibus' pass to the whole Western Front. He returned to an entirely different reception and was met by General Seeley at Poperinghe who expressed his regrets at the way MacDonald had been treated. They set off for the front at YpresYpresYpres is a Belgian municipality located in the Flemish province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the city of Ypres and the villages of Boezinge, Brielen, Dikkebus, Elverdinge, Hollebeke, Sint-Jan, Vlamertinge, Voormezele, Zillebeke, and Zuidschote...

and soon found themselves in the thick of an action in which both behaved with the utmost coolness. Later, MacDonald was received by the Commander-in-Chief at St OmerSaint-OmerSaint-Omer , a commune and sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department west-northwest of Lille on the railway to Calais. The town is named after Saint Audomar, who brought Christianity to the area....

and made an extensive tour of the front. Returning home, he paid a public tribute to the courage of the French troops, but said nothing then or later of having been under fire himself."

United Kingdom general election, 1918

The United Kingdom general election of 1918 was the first to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918, which meant it was the first United Kingdom general election in which nearly all adult men and some women could vote. Polling was held on 14 December 1918, although the count did...

", which saw the Liberal David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

coalition government win a huge majority.

MacDonald stood for Parliament in the 1921 Woolwich East by-election

Woolwich East by-election, 1921

The Woolwich East by-election, 1921 was a parliamentary by-election held on 2 March 1921 for the British House of Commons constituency of Woolwich East, in the Metropolitan Borough of Woolwich in London....

, and lost to war veteran and Victoria Cross

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross is the highest military decoration awarded for valour "in the face of the enemy" to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries, and previous British Empire territories....

winner Robert Gee

Robert Gee

Captain Robert Gee VC MC was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces....

. In 1922 the Conservatives left the coalition and Bonar Law, who had taken over from Lloyd George, called an election on 26 October. MacDonald was returned to the House as MP for Aberavon

Aberavon (UK Parliament constituency)

Aberavon is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It returns one Member of Parliament by the first past the post system.-History:...

in Wales and his rehabilitation was complete; the Labour New Leader wrote that his election was

"enough in itself to transform our position in the House. We have once more a voice which must be heard."'By now the party was reunited and MacDonald was re-elected as Leader. The Liberals by this point were in rapid decline and at the 1922 election Labour became the main opposition party to the Conservative government of Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, KG, PC was a British Conservative politician, who dominated the government in his country between the two world wars...

, making MacDonald Leader of the Opposition. By this time he had moved away from the Labour left and abandoned the socialism of his youth — he strongly opposed the wave of radicalism that swept through the labour movement in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917

Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution is the collective term for a series of revolutions in Russia in 1917, which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. The Tsar was deposed and replaced by a provisional government in the first revolution of February 1917...

— and became a determined enemy of Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

. Unlike the French Socialist Party and the German SPD

Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

, the Labour Party did not split and the Communist Party of Great Britain

Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain was the largest communist party in Great Britain, although it never became a mass party like those in France and Italy. It existed from 1920 to 1991.-Formation:...

remained small and isolated.

Although he was a gifted speaker, MacDonald became noted for 'woolly' rhetoric such as the occasion at the Labour Party Conference of 1930 at Llandudno when he appeared to imply unemployment could be solved by encouraging the jobless to return to the fields "where they till and they grow and they sow and they harvest". Equally there were times it was unclear what his policies were. There was already some unease in the party about what he would do if Labour was able to form a government. At the 1923 election the Conservatives lost their majority, and when they lost a vote of confidence in the House in January 1924 King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

called on MacDonald to form a minority Labour government, with the tacit support of the Liberals under Asquith from the corner benches. MacDonald thus became the first Labour Prime Minister, the first from a working-class background and one of the very few without a university education.

First government (1924)

MacDonald took the post of Foreign Secretary as well as Prime MinisterPrime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

in January 1924 and made it clear that his main priority was to undo the damage which he believed had been caused by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

, by settling the reparations

World War I reparations

World War I reparations refers to the payments and transfers of property and equipment that Germany was forced to make under the Treaty of Versailles following its defeat during World War I...

issue and coming to terms with Germany. He left domestic matters to his ministers, including J.R. Clynes

John Robert Clynes

John Robert Clynes was a British trade unionist and Labour Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament for 35 years, and led the party in its breakthrough at the 1922 general election...

as Lord Privy Seal

Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal is the fifth of the Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and above the Lord Great Chamberlain. The office is one of the traditional sinecure offices of state...

, Philip Snowden as Chancellor of the Exchequer

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is the title held by the British Cabinet minister who is responsible for all economic and financial matters. Often simply called the Chancellor, the office-holder controls HM Treasury and plays a role akin to the posts of Minister of Finance or Secretary of the...

and Henderson as Home Secretary

Home Secretary

The Secretary of State for the Home Department, commonly known as the Home Secretary, is the minister in charge of the Home Office of the United Kingdom, and one of the country's four Great Offices of State...

. King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

noted in his diary that "He wishes to do the right thing...Today 23 years ago dear Grandmama died. I wonder what she would have thought of a Labour Government!"

The Government was only to last nine months and did not have a majority in either House of the Parliament, nevertheless it was still able to support the unemployed with the extension of benefits and amendments to the Insurance Acts. In a personal triumph for John Wheatley

John Wheatley

John Wheatley was a Scottish socialist politician. He was a prominent figure of the Red Clydeside era.Wheatley was born in Bonmahon, County Waterford, Ireland, to Thomas and Johanna Wheatley. In 1876 the family moved to Braehead, Lanarkshire in Scotland...

, Minister for Health, a Housing Act was passed which greatly expanded municipal housing for low paid workers.

MacDonald took the decision in March 1924 to end construction work on the Singapore

Singapore

Singapore , officially the Republic of Singapore, is a Southeast Asian city-state off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, north of the equator. An island country made up of 63 islands, it is separated from Malaysia by the Straits of Johor to its north and from Indonesia's Riau Islands by the...

military base despite strong opposition from the Admiralty. MacDonald believed the building of the base would endanger the disarmament conference; the First Sea Lord

First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord is the professional head of the Royal Navy and the whole Naval Service; it was formerly known as First Naval Lord. He also holds the title of Chief of Naval Staff, and is known by the abbreviations 1SL/CNS...

Lord Beatty

David Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty

Admiral of the Fleet David Richard Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty, GCB, OM, GCVO, DSO was an admiral in the Royal Navy...

considered the absence of such a base as dangerously imperilling British trade and territories east of Aden

Aden

Aden is a seaport city in Yemen, located by the eastern approach to the Red Sea , some 170 kilometres east of Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000. Aden's ancient, natural harbour lies in the crater of an extinct volcano which now forms a peninsula, joined to the mainland by a...

, and would mean the security of the British Empire in the Far East being dependent on the goodwill of Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

.

In June, MacDonald convened a conference in London of the wartime Allies, and achieved an agreement on a new plan for settling the reparations issue and the French occupation of the Ruhr

Ruhr

The Ruhr is a medium-size river in western Germany , a right tributary of the Rhine.-Description:The source of the Ruhr is near the town of Winterberg in the mountainous Sauerland region, at an elevation of approximately 2,200 feet...

. German delegates then joined the meeting, and the London Settlement was signed. This was followed by an Anglo-German commercial treaty. Another major triumph for MacDonald was the conference held in London in July–August 1924 to deal with the implementation of the Dawes Plan

Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan was an attempt in 1924, following World War I for the Triple Entente to collect war reparations debt from Germany...

. MacDonald, who accepted the view of the economist John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes of Tilton, CB FBA , was a British economist whose ideas have profoundly affected the theory and practice of modern macroeconomics, as well as the economic policies of governments...

of German reparations

World War I reparations

World War I reparations refers to the payments and transfers of property and equipment that Germany was forced to make under the Treaty of Versailles following its defeat during World War I...

as impossible to pay successfully pressured the French Premier Édouard Herriot

Édouard Herriot

Édouard Marie Herriot was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic who served three times as Prime Minister and for many years as President of the Chamber of Deputies....

into a whole series of concessions to Germany. A British onlooker commented that “The London Conference was for the French 'man in the street' one long Calvary...as he saw M. Herriot abandoning one by one the cherished possessions of French preponderance on the Reparations Commission, the right of sanctions in the event of German default, the economic occupation of the Ruhr, the French-Belgian railroad Régie, and finally, the military occupation of the Ruhr within a year.” MacDonald was hugely proud of what had been achieved; this was the pinnacle of his short-lived administration's achievements. In September he made a speech to the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

Assembly in Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

, the main thrust of which was for general European disarmament

Disarmament

Disarmament is the act of reducing, limiting, or abolishing weapons. Disarmament generally refers to a country's military or specific type of weaponry. Disarmament is often taken to mean total elimination of weapons of mass destruction, such as nuclear arms...

which was received with great acclamation.

But before all of this the United Kingdom had recognised the Soviet Union and MacDonald informed parliament in February 1924 that negotiations would begin to negotiate a treaty with the Soviet Union. The treaty was to cover Anglo-Soviet trade and the situation of the British bondholders who had contracted with the pre-revolutionary Russian government and which had been rejected by the Bolsheviks. There were in fact to be two treaties. One covering commercial matters and the other to cover a fairly vague future discussion on the problem of the bondholders. If and when the treaties were signed, then the British government would conclude a further treaty and guarantee a loan to the Bolsheviks. The treaties were popular neither with the Conservatives nor with the Liberals who, in September, criticised the loan so vehemently that negotiation with them seemed impossible.

However, it was the "Campbell Case

Campbell Case

The Campbell Case of 1924 involved charges against a British Communist newspaper editor for alleged "incitement to mutiny" caused by his publication of a provocative open letter to members of the military...

" — the abrogation of prosecuting the left-wing newspaper

Newspaper

A newspaper is a scheduled publication containing news of current events, informative articles, diverse features and advertising. It usually is printed on relatively inexpensive, low-grade paper such as newsprint. By 2007, there were 6580 daily newspapers in the world selling 395 million copies a...

the Workers Weekly — that determined its fate. The Conservatives put forth a censure motion, to which the Liberals added an amendment. MacDonald's Cabinet resolved to treat both motions as matters of confidence, which if passed, would necessitate a dissolution of government. The Liberal amendment carried and the King granted MacDonald a dissolution of parliament the following day. The issues which dominated the election campaign were, unsurprisingly, the Campbell case and the Russian treaties which soon combined into the single issue of the Bolshevik threat.

The Zinoviev letter

On 25 October 1924, just 4 days before the election, the Daily MailDaily Mail