.gif)

Publius Licinius Crassus (son of triumvir)

Encyclopedia

Publius Licinius Crassus (86?/82? BC – 53 BC) was one of two sons of the triumvir

Marcus Licinius Crassus

and Tertulla. He belonged to the last generation of Roman nobiles

who came of age and began a political career before the collapse of the Republic

. His peers included Marcus Antonius, Marcus Junius Brutus

, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

, the poet Gaius Valerius Catullus, and the historian Gaius Sallustius Crispus.

Publius Crassus served under Julius Caesar

in Gaul

58–56 BC. Too young to receive a formal commission from the senate

, Publius distinguished himself as a commanding officer in campaigns among the Armorica

n nations (Brittany

) and in Aquitania

. He was highly regarded by Caesar and also by Cicero

, who praised his speaking ability and good character. Upon his return to Rome, Publius married Cornelia Metella

, the intellectually gifted daughter of the optimate Metellus Scipio

, and began his active political career as a monetalis

and by providing a security force during his father's campaign for a second consulship

.

Publius’s promising career was cut short when he died along with his father

in an ill-conceived war against the Parthian Empire

. Cornelia, with whom he probably had no children, then married the much older Pompeius Magnus

("Pompey the Great").

Scholarly opinion is divided as to whether Publius or his brother Marcus was the elder, but with Roman naming conventions

, the eldest son almost always carries on his father's name, including the praenomen

, or first name, while younger sons are named for a grandfather or uncle. The achievements of Publius, named after his grandfather (consul in 97 BC)

and uncle, eclipse those of his brother to such an extent that some have questioned the traditional birth order

. Both Ronald Syme

and Elizabeth Rawson

, however, have argued vigorously for a family dynamic that casts Marcus as the older but Publius as the more talented younger brother.

in his Life of Crassus as stable and orderly. The biographer is often harshly critical of the elder Crassus's shortcomings, particularly moralizing his greed, but makes a point of contrasting the triumvir's family life. Despite his great wealth, Crassus is said to have avoided excess and luxury at home. Family meals were simple, and entertaining was generous but not ostentatious; Crassus chose his companions during leisure hours on the basis of personal friendship as well as political utility. Although the Crassi, as noble plebeians

, would have displayed ancestral images in their atrium, they did not lay claim to a fictionalized genealogy

that presumed divine or legendary ancestors, a practice not uncommon among the Roman nobility. The elder Crassus, even as the son of a consul

and censor, had himself grown up in a modestly kept and multigenerational house; the passage of sumptuary law

s had been among his father's political achievements.

In marrying the widow of his brother, who had been killed during the Sullan civil wars, Marcus Crassus observed an ancient Roman custom that had become old-fashioned in his own time. Publius, unlike many of his peers, had parents who remained married for nearly 35 years, until the elder Crassus's death; by contrast, Pompeius Magnus

married five times and Julius Caesar at least three. Crassus remained married to Tertulla "despite attacks on her reputation." It was rumored that a family friend, Quintus Axius of Reate, was the biological father of one of her two sons. Plutarch reports a joke by Cicero that made reference to a strong resemblance between Axius and one of the boys.

is noted as evidence of Crassus’s parsimony, it has been suggested that in failing to enrich himself at Crassus's expense Alexander asserted a positive philosophical stance disregarding material possessions. The Peripatetics of the time differed little from the Old Academy

represented by Antiochus of Ascalon

, who placed emphasis on knowledge as the supreme value

and on the Aristotelian

conception of human beings as by nature political (a zōon politikon, "creature of politics"). This view of man as a "political animal" would have been congenial to the family political dynamism of the Licinii Crassi.

The Peripatetics and Academics

The Peripatetics and Academics

, according to Cicero, provided the best oratorical

training; while the Academics drilled in rebuttal

, he says, the Peripatetics excelled at rhetorical theory

and also practiced debating

both sides of an issue. The young Crassus must have thrived on this training, for Cicero praises his abilities as a speaker and in the Brutus

places him in the company of gifted young orators whose lives ended before they could fulfill their potential:

The secondary education

of a Roman male of the governing classes typically required a stint as a contubernalis (literally a “tentmate”, a sort of military intern or apprentice) following the assumption of the toga virilis around the age of 15 and before assuming formal military duties. Publius, his brother Marcus, and Decimus Brutus may have been contubernales during Caesar's propraetorship in Spain

(61–60 BC). Publius’s father and grandfather had strong ties to Spain: his grandfather had earned his triumph

from the same province of Hispania Ulterior

, and during Sulla's first civil war

his father had found refuge among friends there, avoiding the fate of Publius's uncle and grandfather. Caesar’s field commission

of Publius in Gaul indicates a high level of confidence, perhaps because he had trained the young man himself and knew his abilities.

Little else is known about Publius's philosophical predispositions or political sympathies. Despite his active support on behalf of his father in the elections for 55 BC and his ties to Caesar, he admired and was loyal to Cicero and played a mediating role between Cicero and the elder Crassus, who was often at odds with the outspoken orator. In his friendship with Cicero, Publius showed a degree of political independence. Cicero seems to have hoped that he could steer the talented young man away from a popularist

and militarist

path toward the example of his consular grandfather, whose political career was traditional and moderate, or toward modeling himself after the orator Licinius Crassus

about whom Cicero so often wrote. Cicero almost always speaks of young Crassus with approval and affection, criticizing only his impatient ambition.

, which Caesar never identifies, has been a subject of debate. Although he held commands, Publius was neither an elected military tribune

nor legatus

appointed by the senate

, though the Greek historian Cassius Dio contributes to the confusion by applying Greek

terminology (ὑπεστρατήγει, hupestratêgei

) to Publius that usually translates the rank expressed in Latin

by legatus. Those who have argued that Publius was the elder son have attempted to make a quaestor

of him. Caesar's omission, however, supports the view that the young Crassus held no formal rank, as the Bellum Gallicum

consistently identifies officers with regard to their place in the military chain of command

. Publius is introduced in the narrative only as adulescens, “tantamount to a technical term for a young man not holding any formal post.” The only other Roman Caesar calls adulescens is Decimus Brutus

, who also makes his first appearance in history in the Bellum Gallicum. In the third year of the war, Caesar refers to Publius as dux

, a non-technical term of military leadership that he uses elsewhere only in reference to Celtic generals. The informality of the phrase is enhanced by a descriptive adulescentulus; in context, Publius is said to be with his men as an adulescentulo duce, their "very young" or "under-age leader."

In the first year of the Gallic Wars

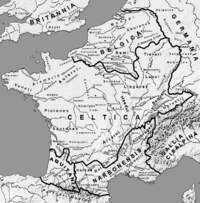

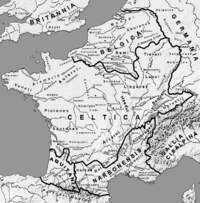

In the first year of the Gallic Wars

, Caesar and his Celtic Aeduan

allies fought a defensive

campaign

against the Celtic Helvetii

, and waged an offensive

against the Germanic

Suebi

and their allies, led by Ariovistus

. During the decisive battle against the Suebi that brought the first year of fighting to its conclusion, Publius Crassus was given command of the cavalry

. In 58 BC, Caesar’s cavalry auxiliaries

numbered 4,000, comprising regiments from the Aedui

and from the Gallic

nations of Gallia Transalpina, already a Roman province

. In Caesar’s army, the primary strategic applications of cavalry were reconnaissance

and intelligence gathering

, conducted by detachments

of exploratores (“scouts”) and speculatores (“spies”); communications

; patrol

s, including advance parties and guard units on the flanks of the army on the march; skirmishing

, and securing the territory after fighting by preventing the flight of surviving enemy. The cavalry charge was infrequent. In the opening stage of the war against the Helvetii

, Caesar had retained a Gallic command structure

; a lack of strategic coordination, exacerbated by conflicting loyalties, led to poor performance, which Caesar sought to correct with a more centralized command. Publius Crassus is the first Roman named as a cavalry commander in the war, and was perhaps given the task of restructuring.

After several days of Roman provocation that produced only skirmishes, the Suebi responded with a sudden attack that preempted standard Roman tactics; Caesar says that the army was unable to release a volley of javelins (pila

), which ordinarily would have been preceded by a cavalry skirmish. Instead, Crassus and the auxiliaries seem to have remained on the periphery of action. Caesar gives Crassus credit for accurately assessing the status of the battle from his superior vantage point and for ordering in the third line of infantry at the critical moment. Initiative is implied. After the Suebi were rout

ed, the horsemen pursued those who escaped, but failed to capture Ariovistus.

. In the penultimate chapter of his book on that year’s campaigns, Caesar abruptly reveals that he had placed Publius Crassus in command of the 7th Legion, which had suffered heavy casualties against the Nervii

at the recent Battle of the Sabis

; Publius's role in this battle goes unremarked. Caesar says that in the aftermath he sent Crassus west to Armorica

(Brittany

) while he himself headed east to lay siege to the stronghold of the Aduatuci

.

Scholars have rarely tried to interpret Caesar's decision to send a young, relatively inexperienced officer with a single legion to secure a major geographical region inhabited by multiple civitates, while the commander-in-chief himself lay siege to a single town with the remaining seven legions of his army and a full staff of senior legates and some or most of the tribunes. Crassus’s Armorican mission is reported so elliptically that Caesar’s chronology and veracity have been questioned, most pointedly by the contrarian scholar Michel Rambaud, who insisted that the 7th Legion must have detached for its mission prior to the Battle of the Sabis. Crassus is credited with bringing several polities

Scholars have rarely tried to interpret Caesar's decision to send a young, relatively inexperienced officer with a single legion to secure a major geographical region inhabited by multiple civitates, while the commander-in-chief himself lay siege to a single town with the remaining seven legions of his army and a full staff of senior legates and some or most of the tribunes. Crassus’s Armorican mission is reported so elliptically that Caesar’s chronology and veracity have been questioned, most pointedly by the contrarian scholar Michel Rambaud, who insisted that the 7th Legion must have detached for its mission prior to the Battle of the Sabis. Crassus is credited with bringing several polities

or “nations” under treaty

, but Caesar says nothing about military operations:

Crassus and the 7th then winter among the Andes

, a Gallic polity whose territory corresponds roughly with the diocese of Angers

(Anjou

) in the French department Maine-et-Loire

. Although Caesar locates the Andes “near the Atlantic,” they held no coast and were located inland along the Loire

river.

Caesar is compelled to modify his assessment of the situation when he writes his account of the third year of the war, in which he himself plays a diminished role and which is markedly shorter than his other six books. Instead, Book 3 of the Bellum Gallicum focusses on Sulpicius Galba

’s travails in the Alps

, and campaigns led by the two junior officers Publius Crassus and Decimus Brutus.

s and military tribunes, among them four named officers of equestrian status who are seized as hostages by three Gallic polities in collusion. The four are T. Terrasidius

, held by the Esubii; M. Trebius Gallus, by the Coriosolites; and Q. Velanius and T. Silius, both by the Veneti.

Whether the Gauls and the Romans understood each other’s laws and customs pertaining to hostage-taking is at issue here as elsewhere in the course of the war, and the actions of Publius Crassus are difficult to reconstruct. The Latin word for hostage, (plural ), may translate but not necessarily correspond in legal application with the Celtic congestlos (in Gaulish

). For both Romans and Celts, the handing over of hostages was often a formally negotiated term in a treaty; among the Celts, however, hostages were also exchanged as a pledge of mutual alliance with no loss of status, a practice that should be placed in the context of other Celtic social institutions such as fosterage

and political alliance through marriage. Among the Celtic and Germanic peoples, hostage arrangements seem to have been a more mutually effective form of diplomatic pressure than was the always-onesided taking of hostages by the Romans.

A concept of international law

, expressed in Latin by the phrase ius gentium

, existed by custom and consensus, and not in any written code or sworn treaty

. By custom, the safety of hostages was guaranteed unless parties to a treaty violated its terms, in which case the subjecting of hostages to punitive actions such as torture or execution was not regarded as violating the ius gentium. If the Armoricans believed themselves to hold the four Romans as hostages in the sense of congestloi, it is unclear what negotiations Publius Crassus had undertaken. “Caesar liked energy and enterprise in young aristocrats,” Syme remarked, “a predilection not always attended with happy results.” Caesar reacted with military force.

In writing the Bellum Gallicum, Caesar often elides legal and administrative arrangements in favor of military narrative. The situation faced by Publius Crassus in Brittany involved both the prosaic matter of logistics

(i.e., feeding the legion under his command) as well as diplomacy among multiple polities, much of which had to be conducted on initiative during Caesar's absence. The building of a Roman fleet on the Loire river during the winter of 57–56 BC has been interpreted by several modern scholars as preparation for an invasion of Britain

, to which the Armoricans would have objected as a threat to their own trade relations with the island. Caesar, at any rate, is most expansive about the exciting naval battle that ensues from the crisis.

When he received reports of the hostage situation in Armorica, Caesar had not yet returned to the front

from his administrative winter quarters in Ravenna, where he had met with Publius’s father for political deal-making prior to the more famous triumviral conference at Luca

in April. Caesar makes haste, and in the summer of 56 BC, the campaign against the Veneti and their allies is conducted by Decimus Brutus as a naval operation. Caesar gives no explanation for transferring Crassus from command on the Armorican front. The Romans are eventually victorious, but the fate of the hostages is left unstated, and in a break with his policy in working with the Gallic aristocracy over the previous two years, Caesar orders the execution of the entire Venetian senate.

, this time with a force consisting of twelve Roman legionary cohorts

, allied Celtic cavalry and volunteers from Gallia Narbonensis

. Ten cohorts is the standard complement of the Caesarian legion, and the twelve cohorts are not identified by any unit number. Caesar relates Publius’s challenges and successes at some length and without any ambiguity about their military nature. Cassius Dio provides a synopsis, which does not accord in every detail with the account of Caesar:

Caesar regards the victories of Publius Crassus as impressive for several reasons. Crassus was only about 25 at the time. He was greatly outnumbered, but he recruited both new Celtic allies and called up provincial forces from southern Gaul; a thousand of his Celtic cavalry remain under his command and loyal to him till his death. Caesar seems almost to present a military résumé for Crassus that outlines the qualities of a good officer. The young dux successfully brought the power of war machines

to bear in laying siege to a stronghold of the Sotiates; upon surrender, he showed clemency, a quality on which Caesar prided himself, toward the enemy commander Adcantuannus. Crassus solicited opinions from his officers at a war council

and achieved consensus on a plan of action. He gathered intelligence and demonstrated his foresight and strategic thinking, employing tactics of stealth, surprise, and deception. Caesar further makes a point of Crassus's attention to logistics and supply lines

, which may have been a deficiency on the Armorican mission. Ultimately, Crassus was able to out-general experienced men who had trained in Roman military tactics with the gifted rebel Quintus Sertorius

on the Spanish front of the civil wars in the late 80s and 70s BC.

aristocrat Publius Clodius Pulcher

. Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Crassus were eventually elected to their second joint consulship for the year of 55. Several steps were taken during this time to advance Publius's career.

s, authorized to issue coinage, most likely in the year of his father’s consulship. In the late Republic, this office was a regular preliminary to the political career track

for senators’ sons, to be followed by a run for quaestor

when the age requirement of 30 was met.

Common among the surviving coins issued by Publius Crassus is a denarius

depicting a bust

of Venus, perhaps a reference to Caesar's legendary genealogy, and on the reverse an unidentified female figure standing by a horse. The short-skirted equestrian holds the horse's bridle in her right hand, with a spear in her left. A cuirass and shield appear in the background at her feet. She may be an allegorical

representation of Gallia

, to commemorate Crassus's military achievements in Gaul and to honor the thousand Gallic cavalry who were deployed with him for Syria

.

into the college

of augur

s, replacing the late Lucius Licinius Lucullus

, a staunch conservative

in politics. Although the augurs held no direct political power, their right to withhold religious ratification could amount to a veto

. It was a prestigious appointment that indicates great expectations for Publius’s future. The vacancy left in the augural college by Publius’s premature death only two years later was filled by Cicero.

, she was “the heiress of the last surviving branch of the Scipiones

.” Publius would have been in his late twenties. His military service abroad had postponed marriage to a later age than a Roman noble typically took a wife. The date of their betrothal goes unrecorded, but if Cornelia had long been the desired bride, she would have been too young to marry before Publius left for Gaul, and his worth as a husband may not have been as evident. The political value of the marriage for Publius lay in family ties to the so-called optimates

, a continually realigning faction of conservative senators who sought to preserve the traditional prerogatives of the aristocratic oligarchy

and to prevent exceptional individuals from dominating through direct appeal to the people or the amassing of military power. Publius’s brother had been married to a daughter of Q. Caecilius Metellus Creticus

(consul 69 BC), probably around 63–62 BC; both matches signal their father’s desire for rapprochement

with the optimates, despite his working arrangements with Caesar and Pompeius, an indication that perhaps the elder Crassus was more conservative than some have thought.

In a letter from February 55 BC, Cicero mentions the presence of Publius Crassus at a meeting held at his father’s house. During these political negotiations, it was agreed that Cicero would not oppose a legatio, or state-sponsored junket, to the East by his longtime enemy Clodius Pulcher

, in exchange for Marcus Crassus supporting an unidentified favor sought by Cicero. Although Clodius has sometimes been regarded as an agent or ally of Crassus, it is unclear whether his trip, probably to visit Byzantium

or Galatia

, was connected to Crassus’s own intentions in the East.

The triumviral negotiations at Ravenna and Luca had resulted in the prolongment of Caesar's Gallic command and the granting of a extended five-year proconsul

ar province for each of the consuls of 55 BC. The Spanish provinces

went to Pompeius; Crassus arranged to have Syria

, with the transparent intention of launching a war against Parthia

. Some Romans opposed the war. Cicero calls it a war nulla causa (“with no justification”), on the grounds that Parthia had a treaty with Rome. Others may have objected less to a war with Parthia than to the attempt of the triumvirate to amass power by waging it. Despite objections and a host of bad omens, Marcus Crassus set sail from Brundisium in November 55 BC.

The notoriously wealthy Marcus Crassus was around sixty and hearing-impaired when he embarked on the Parthian invasion. Plutarch in particular regards greed as his motive; modern historians tend toward envy and rivalry, since Crassus’ faded military reputation was inferior to that of Pompeius and, after five years of war in Gaul, to that of Caesar. Elizabeth Rawson, however, suggested that in addition to these or other practical objectives, the war was meant to provide an arena for Publius’s abilities as a general, which he had begun to demonstrate so vividly in Gaul. Cicero implies as much when he enumerates Publius's many fine qualities (see above) and then mourns and criticizes his young friend's destructive desire for gloria:

Publius presumably helped with preparations for the war. Both Pompeius and Crassus levied

troops throughout Italy. Publius may have organized these efforts in the north, as he is said to have departed for Parthia from Gaul (probably Cisalpina

). His thousand cavalry from Celtica (present-day France and Belgium), auxilia

provided by technically independent allies, were likely to have been stationed in Cisalpina; it is questionable whether the thousand-strong force he used to pressure elections in January 55 BC were these same men, as the employment of barbarians within Rome should have been viewed as outrageous enough to provoke comment.

Publius's activities in 54 BC are unrecorded, but he and his Celtic cavalry troopers did not join his father in Syria until the winter of 54–53 BC, a year after the elder Crassus's departure. His horsemen may have been needed in Gaul as Caesar dealt with a renewed threat from Germanic tribes

from across the Rhine and launched his first invasion of Britannia

.

Despite opposition to the war, Marcus Crassus was criticized for doing little to advance the invasion during the first year of his proconsulship. Upon entering winter quarters, he spent his time on the 1st-century BC equivalent of number-crunching and wealth management, rather than organizing his troops and engaging in diplomatic efforts to gain allies. Only after the arrival of Publius Crassus did he launch the war, and even that beginning was ill-omened. After an inventory of the treasury at the Temple of Atargatis

, Hierapolis, Publius stumbled at the gate and his father tripped over him. The reporting of this portent, fictional or not, suggests "that Publius was seen as the true cause of the disaster."

The military advance was likewise attended by a series of bad omens, and the elder Crassus was frequently at odds with his quaestor, Cassius Longinus

, the future assassin of Caesar. Cassius's strategic sense is presented by Plutarch as superior to that of his commander. Little is said of any contribution by Publius Crassus until a critical juncture at the river Balissus (Balikh), where most of the officers thought the army ought to make camp, rest after a long march through hostile terrain, and reconnoiter

. Marcus Crassus instead is inspired by the eagerness of Publius and his Celtic cavalry to do battle, and after a quick halt in ranks for refreshment, the army marches headlong into a Parthian trap.

Marcus Crassus commanded seven legions, the strength of which has been estimated variously from 28,000 to 40,000, along with 4,000 cavalry and a comparable number of light infantry

. The Roman army vastly outnumbered the force they faced. Although the sandy, open desert

landscape favored cavalry over infantry, the primary value of the Gallo-Roman cavalry was mobility

, not force. By contrast, the thousand heavily armored Parthian cataphract

s carried a long heavy lance

(kontos), the reach of which exceeded the Gallic spear, and the 9,000 Parthian mounted archers were equipped with a compound bow

far superior to that used in Europe, with arrows continually replenished by foot soldiers from a camel

train. The reputation of the legionaries

for excellence in combat at close quarters had been anticipated by the brilliant Parthian general Surena, and answered with heavy cavalry

and long-range weaponry.

Marcus Crassus responded by drawing the legionaries into a defensive square, the shield-wall of which afforded some protection but within which they could accomplish nothing and risked being surrounded. To prevent encirclement, or perhaps in a desperate attempt at diversion, Publius Crassus led out a corps of 1,300 cavalry, primarily his loyal Celtic troopers; 500 archers; and 4,000 elite infantry. The Parthian wing on his side, appearing to abandon their attempt to surround the army, then retreated. Publius pursued. When his force was out of visual and communication range of the main army, the Parthians halted, and Publius found himself in an ambush, rapidly encircled. A military historian describes the scene:

With casualties mounting, Publius decided that a charge was his only option, but most of his men, riddled with arrows, could not respond to the call. Only the Gallic cavalry followed their young leader. The cataphracts returned the effort with a counter charge in which they held the distinct advantage in number and equipment. The weaker, shorter Gallic spears would have had limited effect against the heavy encasing armor of the cataphracts. But when the two forces closed, the lighter armor that left the Gauls more vulnerable also made them more agile. They grabbed hold of the Parthian lances and grappled

to unseat the enemy horsemen. Other Gauls, unhorsed or choosing to dismount, stabbed the Parthian horses in the belly — a tactic that had been employed against Caesar's cavalry by outnumbered Germans the previous year in Gaul.

Eventually, however, the Gauls are forced to retreat, carrying away their wounded leader to a nearby sand dune, where the surviving Roman forces regroup. They drive their horses into the center, then lock shields to form a perimeter. But because of the slope, the men were exposed in tiers to the ceaseless volleys of arrows. Two Greeks who knew the region tried to persuade Publius to escape to a nearby friendly city while his troops held off the enemy. He refused:

The portrait of Publius in Parthia presented by Plutarch contrasts with Caesar's emphasis on the young man's prudence, diplomacy, and strategic thinking. Plutarch describes a leader who is above all keen to fight, brave to the point of recklessness, and tragically heroic in his embrace of death.

Publius Crassus's friends Censorinus

and Megabocchus

and most of the officers commit suicide next to him, and barely 500 men are left alive. The Parthians mutilate Publius’s body and parade his head on the tip of a lance in front of the Roman camp. Taunts are hurled at his father for his son’s greater courage. Plutarch suggests that Marcus Crassus was unable to recover from this psychological blow, and the military situation deteriorated rapidly as a result of his failing leadership. Most of the Roman army was killed or enslaved, except for about 10,000 led by or eventually reunited with Cassius, whose escape has sometimes been characterized as a desertion

. It was one of the worst military disasters in Roman history.

is often said to have been made inevitable by the deaths of two people: Caesar's daughter Julia

, whose political marriage to Pompeius surprised Roman social circles by its affection; and Marcus Crassus, whose political influence and wealth had been a counterweight to the two greater militarists. It would be idle to speculate on what role Publius Crassus might have played either in the civil war or during Caesar's resulting dictatorship

. In many ways, his career follows a course similar to the early life of Decimus Brutus, whose role in the assassination of Caesar was far from foreseeable. Elizabeth Rawson concludes:

At the time of his assassination, Caesar was planning a war against Parthia in retaliation for Carrhae. Marcus Antonius

made the attempt, but suffered another defeat by the Parthians

. The lost standards of the Roman army were finally restored by Augustus

.

Plutarch has Cornelia claim that she tried to kill herself upon learning of her young husband's death. Since Roman widows were not expected to display suicidal grief, Plutarch's dramatization may suggest the depth of Cornelia's emotion at the loss. She is unlikely to have been more than twenty years old at the time. The marriage seems to have produced no children, though Syme speculated about “an unknown daughter.”

As a young and desirable widow, Cornelia then married Pompeius Magnus the following year, becoming his fifth and final wife. Pompeius was more than thirty years her senior. Swift remarriage was not unusual, and perhaps even customary, for aristocratic Romans after the death of a spouse. Despite the age difference, which met with disapproval, this marriage too was said to be affectionate, even passionate. Cornelia was widowed a second time when Pompeius was killed and beheaded in Egypt during the civil war.

In Roman literature, Cornelia becomes almost the type of the gifted woman whose life is delimited by the tragic ambitions of her husbands. In his Life of Pompey, Plutarch has her blame the weight of her own daimon

, heavy with the death of Crassus, for Pompeius's change in fortune. Susan Treggiari remarks that Plutarch's portrayal of the couple “is not to be sharply distinguished from that of star-crossed lovers elsewhere in poetry.” Lucan

dramatizes the couple's fateful romance to an extreme in his often satiric epic Bellum Civile

, where throughout Book 5 Cornelia becomes emblematic of the Late Republic itself, of its greatness and ruin by its most talented men.

to Caesar on behalf of Apollonius, praising him for his loyalty. Since he was manumitted as a term of Publius's will

, he is by Roman custom likely to have taken the name Publius Licinius Apollonius as a freedman

. The highly laudatory account of Publius's death found in Plutarch suggests that Apollonius's biography was a source.

in 54 BC, the year before the Parthian defeat. His service record is undistinguished. In 49 BC, Caesar as dictator appointed Marcus governor of Cisalpine Gaul, the ethnically Celtic north of Italy. He appears to have remained a loyal partisan of Caesar. The Augustan

historian Pompeius Trogus

, of the Celtic Vocontii

, said that the Parthians feared especially harsh retribution in any war won against them by Caesar, because the surviving son of Crassus would be among the Roman forces.

His son, also named Marcus, resembled his uncle Publius in the scope of his military talent and ambition, and was not afraid to assert himself under the hegemony

of Augustus

. This Marcus (consul 30 BC), called by Syme an “illustrious renegade,” was to be the last Roman outside the imperial family to earn a triumph

from the senate.

notes that Augustus built the Temple of Mars Ultor ("Mars the Avenger") to fulfill a vow made to the god if he would help avenge Caesar's murder and the Roman loss at Carrhae, where the Crassorum funera ("deaths of the Crassi") had enhanced the Parthians' sense of superiority. Eutropius, four centuries after the fact, takes note of Publius as “a most illustrious and outstanding young man.”

refers to a treatise

on the Cassiterides

, the semi-legendary Tin Islands off the coast of Britain, written by a Publius Crassus but not now extant. Several scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries, including Theodor Mommsen

and T. Rice Holmes

, thought that this prose work resulted from an expedition during Publius's occupation of Armorica. Scholars of the 20th and early 21st centuries have been more inclined to assign authorship to the grandfather, during his proconsulship in Spain in the 90s BC, in which case Publius's Armorican mission may have been prompted in part by business interests and a desire to capitalize on the earlier survey of resources.

First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate was the political alliance of Gaius Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Unlike the Second Triumvirate, the First Triumvirate had no official status whatsoever; its overwhelming power in the Roman Republic was strictly unofficial influence, and...

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus was a Roman general and politician who commanded the right wing of Sulla's army at the Battle of the Colline Gate, suppressed the slave revolt led by Spartacus, provided political and financial support to Julius Caesar and entered into the political alliance known as the...

and Tertulla. He belonged to the last generation of Roman nobiles

Nobiles

During the Roman Republic, nobilis was a descriptive term of social rank, usually indicating that a member of the family had achieved the consulship. Those who belonged to the hereditary patrician families were noble, but plebeians whose ancestors were consuls were also considered nobiles...

who came of age and began a political career before the collapse of the Republic

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

. His peers included Marcus Antonius, Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus , often referred to as Brutus, was a politician of the late Roman Republic. After being adopted by his uncle he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, but eventually returned to using his original name...

, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus was a Roman politician and general of the 1st century BC and one of the leading instigators of Julius Caesar's assassination...

, the poet Gaius Valerius Catullus, and the historian Gaius Sallustius Crispus.

Publius Crassus served under Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

in Gaul

Gaul

Gaul was a region of Western Europe during the Iron Age and Roman era, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine. The Gauls were the speakers of...

58–56 BC. Too young to receive a formal commission from the senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

, Publius distinguished himself as a commanding officer in campaigns among the Armorica

Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul that includes the Brittany peninsula and the territory between the Seine and Loire rivers, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic coast...

n nations (Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

) and in Aquitania

Gallia Aquitania

Gallia Aquitania was a province of the Roman Empire, bordered by the provinces of Gallia Lugdunensis, Gallia Narbonensis, and Hispania Tarraconensis...

. He was highly regarded by Caesar and also by Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

, who praised his speaking ability and good character. Upon his return to Rome, Publius married Cornelia Metella

Cornelia Metella

Cornelia Metella was the daughter of Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica . She appears in numerous literary sources, including an official dedicatory inscription at Pergamon....

, the intellectually gifted daughter of the optimate Metellus Scipio

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica , in modern scholarship often as Metellus Scipio, was a Roman consul and military commander in the Late Republic. During the civil war between Julius Caesar and the senatorial faction led by Pompeius Magnus , he remained a staunch optimate...

, and began his active political career as a monetalis

Moneyer

A moneyer is someone who physically creates money. Moneyers have a long tradition, dating back at least to ancient Greece. They became most prominent in the Roman Republic, continuing into the empire.-Roman Republican moneyers:...

and by providing a security force during his father's campaign for a second consulship

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

.

Publius’s promising career was cut short when he died along with his father

Battle of Carrhae

The Battle of Carrhae, fought in 53 BC near the town of Carrhae, was a major battle between the Parthian Empire and the Roman Republic. The Parthian Spahbod Surena decisively defeated a Roman invasion force led by Marcus Licinius Crassus...

in an ill-conceived war against the Parthian Empire

Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire , also known as the Arsacid Empire , was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Persia...

. Cornelia, with whom he probably had no children, then married the much older Pompeius Magnus

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

("Pompey the Great").

Early life

- See also: Licinia (gens).

Scholarly opinion is divided as to whether Publius or his brother Marcus was the elder, but with Roman naming conventions

Roman naming conventions

By the Republican era and throughout the Imperial era, a name in ancient Rome for a male citizen consisted of three parts : praenomen , nomen and cognomen...

, the eldest son almost always carries on his father's name, including the praenomen

Praenomen

The praenomen was a personal name chosen by the parents of a Roman child. It was first bestowed on the dies lustricus , the eighth day after the birth of a girl, or the ninth day after the birth of a boy...

, or first name, while younger sons are named for a grandfather or uncle. The achievements of Publius, named after his grandfather (consul in 97 BC)

Publius Licinius Crassus Dives

Publius Licinius Crassus Dives was a member of the respected and prominent Crassi branch of the plebeian gens Licinia as well as the father of the famed Marcus Licinius Crassus...

and uncle, eclipse those of his brother to such an extent that some have questioned the traditional birth order

Birth order

Birth order is defined as a person's rank by age among his or her siblings. Birth order is often believed to have a profound and lasting effect on psychological development...

. Both Ronald Syme

Ronald Syme

Sir Ronald Syme, OM, FBA was a New Zealand-born historian and classicist. Long associated with Oxford University, he is widely regarded as the 20th century's greatest historian of ancient Rome...

and Elizabeth Rawson

Elizabeth Rawson

Elizabeth Donata Rawson was a classical scholar known primarily for her work in the intellectual history of the Roman Republic and her biography of Cicero.-Early life:...

, however, have argued vigorously for a family dynamic that casts Marcus as the older but Publius as the more talented younger brother.

Family environment

Publius grew up in a traditional household that was characterized by PlutarchPlutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

in his Life of Crassus as stable and orderly. The biographer is often harshly critical of the elder Crassus's shortcomings, particularly moralizing his greed, but makes a point of contrasting the triumvir's family life. Despite his great wealth, Crassus is said to have avoided excess and luxury at home. Family meals were simple, and entertaining was generous but not ostentatious; Crassus chose his companions during leisure hours on the basis of personal friendship as well as political utility. Although the Crassi, as noble plebeians

Plebs

The plebs was the general body of free land-owning Roman citizens in Ancient Rome. They were distinct from the higher order of the patricians. A member of the plebs was known as a plebeian...

, would have displayed ancestral images in their atrium, they did not lay claim to a fictionalized genealogy

Genealogy

Genealogy is the study of families and the tracing of their lineages and history. Genealogists use oral traditions, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kinship and pedigrees of its members...

that presumed divine or legendary ancestors, a practice not uncommon among the Roman nobility. The elder Crassus, even as the son of a consul

Roman consul

A consul served in the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic.Each year, two consuls were elected together, to serve for a one-year term. Each consul was given veto power over his colleague and the officials would alternate each month...

and censor, had himself grown up in a modestly kept and multigenerational house; the passage of sumptuary law

Sumptuary law

Sumptuary laws are laws that attempt to regulate habits of consumption. Black's Law Dictionary defines them as "Laws made for the purpose of restraining luxury or extravagance, particularly against inordinate expenditures in the matter of apparel, food, furniture, etc." Traditionally, they were...

s had been among his father's political achievements.

In marrying the widow of his brother, who had been killed during the Sullan civil wars, Marcus Crassus observed an ancient Roman custom that had become old-fashioned in his own time. Publius, unlike many of his peers, had parents who remained married for nearly 35 years, until the elder Crassus's death; by contrast, Pompeius Magnus

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

married five times and Julius Caesar at least three. Crassus remained married to Tertulla "despite attacks on her reputation." It was rumored that a family friend, Quintus Axius of Reate, was the biological father of one of her two sons. Plutarch reports a joke by Cicero that made reference to a strong resemblance between Axius and one of the boys.

Education

The Peripatetic philosopher Alexander was attached to the household of Crassus and is likely to have contributed to the education of the boys. Although his poor remunerationRemuneration

Remuneration is the total compensation that an employee receives in exchange for the service they perform for their employer. Typically, this consists of monetary rewards, also referred to as wage or salary...

is noted as evidence of Crassus’s parsimony, it has been suggested that in failing to enrich himself at Crassus's expense Alexander asserted a positive philosophical stance disregarding material possessions. The Peripatetics of the time differed little from the Old Academy

Platonic Academy

The Academy was founded by Plato in ca. 387 BC in Athens. Aristotle studied there for twenty years before founding his own school, the Lyceum. The Academy persisted throughout the Hellenistic period as a skeptical school, until coming to an end after the death of Philo of Larissa in 83 BC...

represented by Antiochus of Ascalon

Antiochus of Ascalon

Antiochus , of Ascalon, , was an Academic philosopher. He was a pupil of Philo of Larissa at the Academy, but he diverged from the Academic skepticism of Philo and his predecessors...

, who placed emphasis on knowledge as the supreme value

Value (ethics)

In ethics, value is a property of objects, including physical objects as well as abstract objects , representing their degree of importance....

and on the Aristotelian

Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism is a tradition of philosophy that takes its defining inspiration from the work of Aristotle. The works of Aristotle were initially defended by the members of the Peripatetic school, and, later on, by the Neoplatonists, who produced many commentaries on Aristotle's writings...

conception of human beings as by nature political (a zōon politikon, "creature of politics"). This view of man as a "political animal" would have been congenial to the family political dynamism of the Licinii Crassi.

Platonic Academy

The Academy was founded by Plato in ca. 387 BC in Athens. Aristotle studied there for twenty years before founding his own school, the Lyceum. The Academy persisted throughout the Hellenistic period as a skeptical school, until coming to an end after the death of Philo of Larissa in 83 BC...

, according to Cicero, provided the best oratorical

Oratory

Oratory is a type of public speaking.Oratory may also refer to:* Oratory , a power metal band* Oratory , a place of worship* a religious order such as** Oratory of Saint Philip Neri ** Oratory of Jesus...

training; while the Academics drilled in rebuttal

Rebuttal

In law, rebuttal is a form of evidence that is presented to contradict or nullify other evidence that has been presented by an adverse party. By analogy the same term is used in politics and public affairs to refer to the informal process by which statements, designed to refute or negate specific...

, he says, the Peripatetics excelled at rhetorical theory

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

and also practiced debating

Debate

Debate or debating is a method of interactive and representational argument. Debate is a broader form of argument than logical argument, which only examines consistency from axiom, and factual argument, which only examines what is or isn't the case or rhetoric which is a technique of persuasion...

both sides of an issue. The young Crassus must have thrived on this training, for Cicero praises his abilities as a speaker and in the Brutus

Brutus (Cicero)

Cicero's Brutus is a history of Roman oratory. It is written in the form of a dialogue, in which Brutus and Atticus ask Cicero to describe the qualities of all the leading Roman orators up to their time. It was composed in 46 B.C.-Further reading:*G. V...

places him in the company of gifted young orators whose lives ended before they could fulfill their potential:

The secondary education

Secondary education

Secondary education is the stage of education following primary education. Secondary education includes the final stage of compulsory education and in many countries it is entirely compulsory. The next stage of education is usually college or university...

of a Roman male of the governing classes typically required a stint as a contubernalis (literally a “tentmate”, a sort of military intern or apprentice) following the assumption of the toga virilis around the age of 15 and before assuming formal military duties. Publius, his brother Marcus, and Decimus Brutus may have been contubernales during Caesar's propraetorship in Spain

Hispania

Another theory holds that the name derives from Ezpanna, the Basque word for "border" or "edge", thus meaning the farthest area or place. Isidore of Sevilla considered Hispania derived from Hispalis....

(61–60 BC). Publius’s father and grandfather had strong ties to Spain: his grandfather had earned his triumph

Roman triumph

The Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the military achievement of an army commander who had won great military successes, or originally and traditionally, one who had successfully completed a foreign war. In Republican...

from the same province of Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior

During the Roman Republic, Hispania Ulterior was a region of Hispania roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of modern Spain and extending to all of Lusitania and Gallaecia...

, and during Sulla's first civil war

Sulla's first civil war

Sulla's first civil war was one of a series of civil wars in ancient Rome, between Gaius Marius and Sulla, between 88 and 87 BC.- Prelude - Social War :...

his father had found refuge among friends there, avoiding the fate of Publius's uncle and grandfather. Caesar’s field commission

Brevet (military)

In many of the world's military establishments, brevet referred to a warrant authorizing a commissioned officer to hold a higher rank temporarily, but usually without receiving the pay of that higher rank except when actually serving in that role. An officer so promoted may be referred to as being...

of Publius in Gaul indicates a high level of confidence, perhaps because he had trained the young man himself and knew his abilities.

Little else is known about Publius's philosophical predispositions or political sympathies. Despite his active support on behalf of his father in the elections for 55 BC and his ties to Caesar, he admired and was loyal to Cicero and played a mediating role between Cicero and the elder Crassus, who was often at odds with the outspoken orator. In his friendship with Cicero, Publius showed a degree of political independence. Cicero seems to have hoped that he could steer the talented young man away from a popularist

Populares

Populares were aristocratic leaders in the late Roman Republic who relied on the people's assemblies and tribunate to acquire political power. They are regarded in modern scholarship as in opposition to the optimates, who are identified with the conservative interests of a senatorial elite...

and militarist

Militarism

Militarism is defined as: the belief or desire of a government or people that a country should maintain a strong military capability and be prepared to use it aggressively to defend or promote national interests....

path toward the example of his consular grandfather, whose political career was traditional and moderate, or toward modeling himself after the orator Licinius Crassus

Lucius Licinius Crassus

Lucius Licinius Crassus was a Roman consul. He was considered the greatest Roman orator of his day, by his pupil Cicero.He became consul in 95 BC. During his consulship a law was passed requiring all but citizens to leave Rome, an edict which provoked the Social War...

about whom Cicero so often wrote. Cicero almost always speaks of young Crassus with approval and affection, criticizing only his impatient ambition.

Early military career

Publius Crassus enters the historical record as an officer under Caesar in Gaul. His military rankMilitary rank

Military rank is a system of hierarchical relationships in armed forces or civil institutions organized along military lines. Usually, uniforms denote the bearer's rank by particular insignia affixed to the uniforms...

, which Caesar never identifies, has been a subject of debate. Although he held commands, Publius was neither an elected military tribune

Military tribune

A military tribune was an officer of the Roman army who ranked below the legate and above the centurion...

nor legatus

Legatus

A legatus was a general in the Roman army, equivalent to a modern general officer. Being of senatorial rank, his immediate superior was the dux, and he outranked all military tribunes...

appointed by the senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

, though the Greek historian Cassius Dio contributes to the confusion by applying Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

terminology (ὑπεστρατήγει, hupestratêgei

Strategos

Strategos, plural strategoi, is used in Greek to mean "general". In the Hellenistic and Byzantine Empires the term was also used to describe a military governor...

) to Publius that usually translates the rank expressed in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

by legatus. Those who have argued that Publius was the elder son have attempted to make a quaestor

Quaestor

A Quaestor was a type of public official in the "Cursus honorum" system who supervised financial affairs. In the Roman Republic a quaestor was an elected official whereas, with the autocratic government of the Roman Empire, quaestors were simply appointed....

of him. Caesar's omission, however, supports the view that the young Crassus held no formal rank, as the Bellum Gallicum

Commentarii de Bello Gallico

Commentarii de Bello Gallico is Julius Caesar's firsthand account of the Gallic Wars, written as a third-person narrative. In it Caesar describes the battles and intrigues that took place in the nine years he spent fighting local armies in Gaul that opposed Roman domination.The "Gaul" that Caesar...

consistently identifies officers with regard to their place in the military chain of command

Chain of Command

Chain of Command may refer to:* Chain of command, in a military context, the line of authority and responsibility along which orders are passed* "Chain of Command" , the fifth episode of the first season of Beast Wars...

. Publius is introduced in the narrative only as adulescens, “tantamount to a technical term for a young man not holding any formal post.” The only other Roman Caesar calls adulescens is Decimus Brutus

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus was a Roman politician and general of the 1st century BC and one of the leading instigators of Julius Caesar's assassination...

, who also makes his first appearance in history in the Bellum Gallicum. In the third year of the war, Caesar refers to Publius as dux

Dux

Dux is Latin for leader and later for Duke and its variant forms ....

, a non-technical term of military leadership that he uses elsewhere only in reference to Celtic generals. The informality of the phrase is enhanced by a descriptive adulescentulus; in context, Publius is said to be with his men as an adulescentulo duce, their "very young" or "under-age leader."

Entering Celtica, 58 BC

Gallic Wars

The Gallic Wars were a series of military campaigns waged by the Roman proconsul Julius Caesar against several Gallic tribes. They lasted from 58 BC to 51 BC. The Gallic Wars culminated in the decisive Battle of Alesia in 52 BC, in which a complete Roman victory resulted in the expansion of the...

, Caesar and his Celtic Aeduan

Aedui

Aedui, Haedui or Hedui , were a Gallic people of Gallia Lugdunensis, who inhabited the country between the Arar and Liger , in today's France. Their territory thus included the greater part of the modern departments of Saône-et-Loire, Côte-d'Or and Nièvre.-Geography:The country of the Aedui is...

allies fought a defensive

Defense (military)

Defense has several uses in the sphere of military application.Personal defense implies measures taken by individual soldiers in protecting themselves whether by use of protective materials such as armor, or field construction of trenches or a bunker, or by using weapons that prevent the enemy...

campaign

Military campaign

In the military sciences, the term military campaign applies to large scale, long duration, significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of inter-related military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war...

against the Celtic Helvetii

Helvetii

The Helvetii were a Celtic tribe or tribal confederation occupying most of the Swiss plateau at the time of their contact with the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC...

, and waged an offensive

Offensive (military)

An offensive is a military operation that seeks through aggressive projection of armed force to occupy territory, gain an objective or achieve some larger strategic, operational or tactical goal...

against the Germanic

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Indo-European Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.Originating about 1800 BCE from the Corded Ware Culture on the North...

Suebi

Suebi

The Suebi or Suevi were a group of Germanic peoples who were first mentioned by Julius Caesar in connection with Ariovistus' campaign, c...

and their allies, led by Ariovistus

Ariovistus

Ariovistus was a leader of the Suebi and other allied Germanic peoples in the second quarter of the 1st century BC. He and his followers took part in a war in Gaul, assisting the Arverni and Sequani to defeat their rivals the Aedui, after which they settled in large numbers in conquered Gallic...

. During the decisive battle against the Suebi that brought the first year of fighting to its conclusion, Publius Crassus was given command of the cavalry

Roman cavalry

Roman cavalry refers to the horse mounted forces of the Roman army through the many centuries of its existence.- Early cavalry Roman cavalry (Latin: equites Romani) refers to the horse mounted forces of the Roman army through the many centuries of its existence.- Early cavalry Roman cavalry...

. In 58 BC, Caesar’s cavalry auxiliaries

Auxiliaries (Roman military)

Auxiliaries formed the standing non-citizen corps of the Roman army of the Principate , alongside the citizen legions...

numbered 4,000, comprising regiments from the Aedui

Aedui

Aedui, Haedui or Hedui , were a Gallic people of Gallia Lugdunensis, who inhabited the country between the Arar and Liger , in today's France. Their territory thus included the greater part of the modern departments of Saône-et-Loire, Côte-d'Or and Nièvre.-Geography:The country of the Aedui is...

and from the Gallic

Gauls

The Gauls were a Celtic people living in Gaul, the region roughly corresponding to what is now France, Belgium, Switzerland and Northern Italy, from the Iron Age through the Roman period. They mostly spoke the Continental Celtic language called Gaulish....

nations of Gallia Transalpina, already a Roman province

Roman province

In Ancient Rome, a province was the basic, and, until the Tetrarchy , largest territorial and administrative unit of the empire's territorial possessions outside of Italy...

. In Caesar’s army, the primary strategic applications of cavalry were reconnaissance

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance is the military term for exploring beyond the area occupied by friendly forces to gain information about enemy forces or features of the environment....

and intelligence gathering

Military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that exploits a number of information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to commanders in support of their decisions....

, conducted by detachments

Detachment (military)

A detachment is a military unit. It can either be detached from a larger unit for a specific function or be a permanent unit smaller than a battalion. The term is often used to refer to a unit that is assigned to a different base from the parent unit...

of exploratores (“scouts”) and speculatores (“spies”); communications

Military communications

Historically, the first military communications had the form of sending/receiving simple signals . Respectively, the first distinctive tactics of military communications were called Signals, while units specializing in those tactics received the Signal Corps name...

; patrol

Patrol

A patrol is commonly a group of personnel, such as police officers or soldiers, that are assigned to monitor a specific geographic area.- Military :...

s, including advance parties and guard units on the flanks of the army on the march; skirmishing

Skirmisher

Skirmishers are infantry or cavalry soldiers stationed ahead or alongside a larger body of friendly troops. They are usually placed in a skirmish line to harass the enemy.-Pre-modern:...

, and securing the territory after fighting by preventing the flight of surviving enemy. The cavalry charge was infrequent. In the opening stage of the war against the Helvetii

Helvetii

The Helvetii were a Celtic tribe or tribal confederation occupying most of the Swiss plateau at the time of their contact with the Roman Republic in the 1st century BC...

, Caesar had retained a Gallic command structure

Chain of Command

Chain of Command may refer to:* Chain of command, in a military context, the line of authority and responsibility along which orders are passed* "Chain of Command" , the fifth episode of the first season of Beast Wars...

; a lack of strategic coordination, exacerbated by conflicting loyalties, led to poor performance, which Caesar sought to correct with a more centralized command. Publius Crassus is the first Roman named as a cavalry commander in the war, and was perhaps given the task of restructuring.

After several days of Roman provocation that produced only skirmishes, the Suebi responded with a sudden attack that preempted standard Roman tactics; Caesar says that the army was unable to release a volley of javelins (pila

Pilum

The pilum was a javelin commonly used by the Roman army in ancient times. It was generally about two metres long overall, consisting of an iron shank about 7 mm in diameter and 60 cm long with pyramidal head...

), which ordinarily would have been preceded by a cavalry skirmish. Instead, Crassus and the auxiliaries seem to have remained on the periphery of action. Caesar gives Crassus credit for accurately assessing the status of the battle from his superior vantage point and for ordering in the third line of infantry at the critical moment. Initiative is implied. After the Suebi were rout

Rout

A rout is commonly defined as a chaotic and disorderly retreat or withdrawal of troops from a battlefield, resulting in the victory of the opposing party, or following defeat, a collapse of discipline, or poor morale. A routed army often degenerates into a sense of "every man for himself" as the...

ed, the horsemen pursued those who escaped, but failed to capture Ariovistus.

Belgica, 57 BC

The second year of the war was conducted in northern Gaul among the Belgic nationsBelgae

The Belgae were a group of tribes living in northern Gaul, on the west bank of the Rhine, in the 3rd century BC, and later also in Britain, and possibly even Ireland...

. In the penultimate chapter of his book on that year’s campaigns, Caesar abruptly reveals that he had placed Publius Crassus in command of the 7th Legion, which had suffered heavy casualties against the Nervii

Nervii

The Nervii were an ancient Germanic tribe, and one of the most powerful Belgic tribes; living in the northeastern hinterlands of Gaul, they were known to trek long distances to engage in various wars and functions...

at the recent Battle of the Sabis

Battle of the Sabis

The Battle of the Sabis, also known as the Battle of the Sambre or the Battle against the Nervians , was fought in 57 BC in the area known today as Wallonia, between the legions of the Roman Republic and an association of Belgic tribes, principally the Nervii...

; Publius's role in this battle goes unremarked. Caesar says that in the aftermath he sent Crassus west to Armorica

Armorica

Armorica or Aremorica is the name given in ancient times to the part of Gaul that includes the Brittany peninsula and the territory between the Seine and Loire rivers, extending inland to an indeterminate point and down the Atlantic coast...

(Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

) while he himself headed east to lay siege to the stronghold of the Aduatuci

Aduatuci

The Aduatuci or Atuatuci were, according to Caesar, a Germanic tribe formed in east Belgium descended from the Cimbri and Teutones, who are tribes thought to have originated in the area of Denmark. They were allowed to settle in the region by local tribes...

.

Armorica and Aquitania, 56 BC

Polity

Polity is a form of government Aristotle developed in his search for a government that could be most easily incorporated and used by the largest amount of people groups, or states...

or “nations” under treaty

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

, but Caesar says nothing about military operations:

Crassus and the 7th then winter among the Andes

Andes (Andecavi)

The Andecavi or Andegavi, also Andes in Julius Caesar's Bellum Gallicum, were a people of ancient and medieval Aremorica...

, a Gallic polity whose territory corresponds roughly with the diocese of Angers

Roman Catholic Diocese of Angers

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Angers, is a diocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic church, in France. The episcopal see is located in Angers Cathedral, in the city of Angers. The diocese extends over the entire department of Maine-et-Loire....

(Anjou

Anjou

Anjou is a former county , duchy and province centred on the city of Angers in the lower Loire Valley of western France. It corresponds largely to the present-day département of Maine-et-Loire...

) in the French department Maine-et-Loire

Maine-et-Loire

Maine-et-Loire is a department in west-central France, in the Pays de la Loire region.- History :Maine-et-Loire is one of the original 83 departments created during the French Revolution on March 4, 1790. Originally it was called Mayenne-et-Loire, but its name was changed to Maine-et-Loire in 1791....

. Although Caesar locates the Andes “near the Atlantic,” they held no coast and were located inland along the Loire

Loire

Loire is an administrative department in the east-central part of France occupying the River Loire's upper reaches.-History:Loire was created in 1793 when after just 3½ years the young Rhône-et-Loire department was split into two. This was a response to counter-Revolutionary activities in Lyon...

river.

Caesar is compelled to modify his assessment of the situation when he writes his account of the third year of the war, in which he himself plays a diminished role and which is markedly shorter than his other six books. Instead, Book 3 of the Bellum Gallicum focusses on Sulpicius Galba

Servius Sulpicius Galba (praetor 54 BC)

Servius Sulpicius Galba, praetor in 54 BC.As legate of Julius Caesar's 12th Legion during his Gallic Wars, he was defeated by the Nantuates in 57 BC. Later, however, angered due to Caesar's opposition to his campaign for the consulship, he joined the conspiracy with Brutus and Cassius, and was...

’s travails in the Alps

History of the Alps

The Alpine region has been populated since ancient times and, due to its central location, its history has always been closely entwined with that of Europe. Currently the Alps sprawl across eight countries...

, and campaigns led by the two junior officers Publius Crassus and Decimus Brutus.

Hostage crisis

According to Caesar, the young Crassus, facing a shortage of rations, at some unspecified time sent out detachments to procure grain under the command of prefectPrefect

Prefect is a magisterial title of varying definition....

s and military tribunes, among them four named officers of equestrian status who are seized as hostages by three Gallic polities in collusion. The four are T. Terrasidius

Terrasidius

Titus Terrasidius was a Roman Knight of the Equestrian order and an officer of the cavalry in Julius Caesar's Legio VII Claudia. He and other officers of the legion were sent out to negotiate provisions for the winter of 56-55 BC, as Caesar describes in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico:"...

, held by the Esubii; M. Trebius Gallus, by the Coriosolites; and Q. Velanius and T. Silius, both by the Veneti.

Whether the Gauls and the Romans understood each other’s laws and customs pertaining to hostage-taking is at issue here as elsewhere in the course of the war, and the actions of Publius Crassus are difficult to reconstruct. The Latin word for hostage, (plural ), may translate but not necessarily correspond in legal application with the Celtic congestlos (in Gaulish

Gaulish language

The Gaulish language is an extinct Celtic language that was spoken by the Gauls, a people who inhabited the region known as Gaul from the Iron Age through the Roman period...

). For both Romans and Celts, the handing over of hostages was often a formally negotiated term in a treaty; among the Celts, however, hostages were also exchanged as a pledge of mutual alliance with no loss of status, a practice that should be placed in the context of other Celtic social institutions such as fosterage

Fosterage

Fosterage, the practice of a family bringing up a child not their own, differs from adoption in that the child's parents, not the foster-parents, remain the acknowledged parents. In many modern western societies foster care can be organised by the state to care for children with troubled family...

and political alliance through marriage. Among the Celtic and Germanic peoples, hostage arrangements seem to have been a more mutually effective form of diplomatic pressure than was the always-onesided taking of hostages by the Romans.

A concept of international law

International law

Public international law concerns the structure and conduct of sovereign states; analogous entities, such as the Holy See; and intergovernmental organizations. To a lesser degree, international law also may affect multinational corporations and individuals, an impact increasingly evolving beyond...

, expressed in Latin by the phrase ius gentium

Jus gentium

Ius gentium, Latin for "law of nations", was originally the part of Roman law that the Roman Empire applied to its dealings with foreigners, especially provincial subjects...

, existed by custom and consensus, and not in any written code or sworn treaty

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

. By custom, the safety of hostages was guaranteed unless parties to a treaty violated its terms, in which case the subjecting of hostages to punitive actions such as torture or execution was not regarded as violating the ius gentium. If the Armoricans believed themselves to hold the four Romans as hostages in the sense of congestloi, it is unclear what negotiations Publius Crassus had undertaken. “Caesar liked energy and enterprise in young aristocrats,” Syme remarked, “a predilection not always attended with happy results.” Caesar reacted with military force.

In writing the Bellum Gallicum, Caesar often elides legal and administrative arrangements in favor of military narrative. The situation faced by Publius Crassus in Brittany involved both the prosaic matter of logistics

Military logistics

Military logistics is the discipline of planning and carrying out the movement and maintenance of military forces. In its most comprehensive sense, it is those aspects or military operations that deal with:...

(i.e., feeding the legion under his command) as well as diplomacy among multiple polities, much of which had to be conducted on initiative during Caesar's absence. The building of a Roman fleet on the Loire river during the winter of 57–56 BC has been interpreted by several modern scholars as preparation for an invasion of Britain

Britannia

Britannia is an ancient term for Great Britain, and also a female personification of the island. The name is Latin, and derives from the Greek form Prettanike or Brettaniai, which originally designated a collection of islands with individual names, including Albion or Great Britain. However, by the...

, to which the Armoricans would have objected as a threat to their own trade relations with the island. Caesar, at any rate, is most expansive about the exciting naval battle that ensues from the crisis.

When he received reports of the hostage situation in Armorica, Caesar had not yet returned to the front

Front (military)

A military front or battlefront is a contested armed frontier between opposing forces. This can be a local or tactical front, or it can range to a theater...

from his administrative winter quarters in Ravenna, where he had met with Publius’s father for political deal-making prior to the more famous triumviral conference at Luca

Lucca

Lucca is a city and comune in Tuscany, central Italy, situated on the river Serchio in a fertile plainnear the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Lucca...

in April. Caesar makes haste, and in the summer of 56 BC, the campaign against the Veneti and their allies is conducted by Decimus Brutus as a naval operation. Caesar gives no explanation for transferring Crassus from command on the Armorican front. The Romans are eventually victorious, but the fate of the hostages is left unstated, and in a break with his policy in working with the Gallic aristocracy over the previous two years, Caesar orders the execution of the entire Venetian senate.

Conqueror of Aquitania