Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt

Encyclopedia

Theodore Roosevelt

was the 26th (1901–1909) President of the United States

. He had been the 25th Vice President

before becoming President upon the assassination of President William McKinley

. Owing to his charismatic personality and reformist policies, which he called the "Square Deal

", Roosevelt is considered one of the ablest presidents and an icon of the Progressive Era

.

McKinley was shot by an anarchist in Buffalo, New York

McKinley was shot by an anarchist in Buffalo, New York

on September 6, 1901, and died on September 14, putting Roosevelt into the presidency. A few weeks short of his 43rd birthday, he was the youngest person to hold the office. Roosevelt continued McKinley's cabinet and promised to continue McKinley's policies. One of his first notable acts as President was to deliver a 20,000-word address to Congress on December 3, 1901, asking it to curb the power of large corporation

s (called "trusts") "within reasonable limits." For his aggressive attacks on trusts over his two terms he was called a "trust-buster."

Roosevelt relished the Presidency and seemed to be everywhere at once. He took Cabinet

members and friends on long, fast-paced hikes, boxed in the state rooms of the White House, romped with his children, and read voraciously. He was permanently blinded in one eye during one of his boxing bouts.

In 1904, Roosevelt ran for President in his own right and won in a landslide victory.

Building on McKinley's effective use of the press, Roosevelt made the White House

the center of news every day, providing interviews and photo opportunities. He accomplished this after noticing the White House reporters huddled outside in the rain one day; he gave them their own room inside, effectively inventing the presidential press briefing. The grateful press, with unprecedented access to the White House, rewarded Roosevelt with ample coverage. This was helped by Roosevelt's practice of screening out reporters he didn't like.

" between business and labor, Roosevelt pushed several pieces of progressive legislation through Congress

.

Progressivism in the United States

was the most powerful political force of the day, and in the first dozen years of the century Roosevelt was its most articulate spokesman. Progressivism meant expertise, and the use of science, engineering, technology and the new social sciences to identify the nation's problems, and identify ways to eliminate waste and inefficiency and to promote modernization. Roosevelt, trained as a biologist, identified himself and his programs with the mystique of science. The other side of Progressivism was a burning hatred of corruption and a fear of powerful and dangerous forces, such as political machines, the corrupt segment of labor unions and especially the new large corporations — called "trusts" — which seemed to have emerged overnight. Roosevelt, the former deputy sheriff on the Dakota frontier, and police commissioner of New York City, was keenly interested in a law and order. Indeed, he was the first president with significant law enforcement experience, and his moralistic determination set the tone of national politics.

'

Trusts were increasing the central issue in politics, with public opinion fearing that large corporations could impose monopolistic prices to cheat the consumer and squash small independent companies. By 1904, 318 trusts controlled about two-fifths of the nation's manufacturing output, not to mention powerful trusts in non-manufacturing sectors such as railroads, local transit, and banking. Roosevelt decided to do something about it. A few historians credit McKinley with starting the trust-busting era, but most credit Roosevelt, the "Trust Buster." Once President, Roosevelt worked to increase the regulatory power of the federal government. Regulation of railroads was strengthened by the Elkins Act

Trusts were increasing the central issue in politics, with public opinion fearing that large corporations could impose monopolistic prices to cheat the consumer and squash small independent companies. By 1904, 318 trusts controlled about two-fifths of the nation's manufacturing output, not to mention powerful trusts in non-manufacturing sectors such as railroads, local transit, and banking. Roosevelt decided to do something about it. A few historians credit McKinley with starting the trust-busting era, but most credit Roosevelt, the "Trust Buster." Once President, Roosevelt worked to increase the regulatory power of the federal government. Regulation of railroads was strengthened by the Elkins Act

(1903) and especially the Hepburn Act

of 1906, which had the effect of favoring merchants over the railroads. Under his leadership, the Attorney General brought forty-four suits against businesses that were claimed to be monopolies, most notably J.P. Morgan's Northern Securities Company

, a huge railroad combination, and J. D. Rockefeller

's Standard Oil Company. Both were successful, with Standard Oil broken into over 30 smaller companies that eventually competed with one another. To raise the visibility of labor and management issues, he established a new federal Department of Commerce and Labor

.

of 1906, as well as the Meat Inspection Act

of 1906. These laws provided for labeling of foods and drugs, inspection of livestock and mandated sanitary conditions at meatpacking plants. Congress replaced Roosevelt's proposals with a version supported by the major meatpackers who worried about the overseas markets, and did not want small unsanitary plants undercutting their domestic market.

of 1903 was the Administration's first effort at the regulation of railroad rates; it proved ineffective in practice. Roosevelt agreed with the shipping interests who wanted lower rates and a stronger Interstate Commerce Commission

to enforce them. As Roosevelt told Congress, "Above all else, we must strive to keep the highways of commerce open to all on equal terms; and to do this it is necessary to put a complete stop to all rebates." Politically this was action on behalf of shippers; it was assumed that the railroads would always be powerful and no amount of regulation would seriously weaken them. (No one dreamed of a vast highway system carrying millions of trucks and automobiles.)

Roosevelt encountered opposition in his party, led in the Senate by Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, the party leader; Joseph B. Foraker

of Ohio; Chauncey Depew

of New York (the president of the New York Central Railroad),

Stephen Elkins of West Virginia, Philander Knox of Pennsylvania (formerly Roosevelt's Attorney General), and one of his closest personal friends Henry Cabot Lodge

of Massachusetts. Roosevelt therefore planned to rely on a group of Midwestern Republicans, especially William Allison

of Iowa. He wanted to avoid having to collaborate with Ben Tillman of South Carolina, whom he considered "one of the foulest and rottenest demagogues in the whole country." In the end Roosevelt convinced the conservatives that the courts would protect the railroads' interests, and he carried the bill without Tillman.

The Hepburn Act

of 1906 gave the Interstate Commerce Commission

(ICC) the power to set maximum railroad rates and stopped free passes given to friends of the railroad. In addition, the ICC could view the railroads' financial records, a task simplified by standardized booking systems. For any railroad that resisted, the ICC's conditions would be in effect until the outcome of litigation said otherwise. By the Hepburn Act, the ICC's authority was extended to cover bridges, terminals, ferries, sleeping cars, express companies and oil pipelines. Along with the Elkins Act of 1903, the Hepburn Act accomplished one of Roosevelt's major goals, railroad regulation. The main beneficiaries were the merchants who received lower shipping rates.

, putting the issue high on the national agenda. He worked with all the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter, Gifford Pinchot

. Roosevelt was deeply committed to conserving natural resources, and is considered to be the nation's first conservation

President. He encouraged the Newlands Reclamation Act

of 1902 to promote federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed 230 million acres (360,000 mi² or 930,000 km²) under federal protection. Roosevelt set aside more Federal land land national park

s and nature preserves than all of his predecessors combined.

Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service

, signed into law the creation of five National Parks, and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act

, under which he proclaimed 18 new U.S. National Monument

s. He also established the first 51 Bird Reserve

s, four Game Preserves, and 150 National Forests

, including Shoshone National Forest

, the nation's first. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately 230000000 acres (930,777.8 km²).

Gifford Pinchot

had been appointed by McKinley as chief of Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. In 1905, his department gained control of the national forest reserves. Pinchot promoted private use (for a fee) under federal supervision. In 1907, Roosevelt designated 16 million acres (65,000 km²) of new national forests just minutes before a deadline.

In May 1908, Roosevelt sponsored the Conference of Governors

held in the White House, with a focus on natural resources and their most efficient use. Roosevelt delivered the opening address: "Conservation as a National Duty."

In 1903 Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with John Muir

, who had a very different view of conservation, and tried to minimize commercial use of water resources and forests. Working through the Sierra Club

he founded, Muir succeeded in 1905 in having Congress transfer the Mariposa Grove

and Yosemite Valley to the National Park Service

. While Muir wanted nature preserved for the sake of pure beauty, Roosevelt subscribed to Pinchot's formulation, "to make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees."

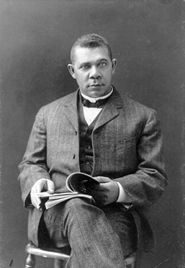

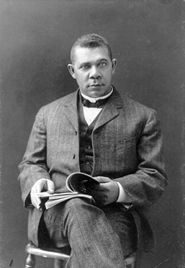

, lacked initiative on most racial issues. Booker T. Washington

, the most important black leader of the day, was the first African American

to be invited to dinner, on October 16, 1901, at the White House, where he discussed politics and racism

with Roosevelt. News of the dinner reached the press two days later. The white public outcry following the dinner was so strong, especially from the Southern states, that Roosevelt never repeated the experiment. Roosevelt was reluctant to use federal authority to enforce the 15th Amendment

to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing voting rights to African Americans.

Publicly, Roosevelt spoke out against racism and discrimination

Publicly, Roosevelt spoke out against racism and discrimination

, and appointed many blacks to lower-level Federal offices, and wrote fondly of the "Buffalo Soldiers," who had fought beside his Rough Riders

at the Battle of San Juan Hill

in Cuba in July 1898. However, soon after returning from San Juan Hill, Roosevelt changed his story concerning African American Soldiers and their conduct in battle saying "Under the strain the colored infantrymen (who had none of their white officers) began to get a little uneasy and drift to the rear… This I could not allow." Roosevelt opposed school segregation

, having ended the practice in New York State during his governorship. Roosevelt rejected anti-Semitism

—he was the first to appoint a Jew, Oscar S. Straus, to the cabinet.

Like most intellectuals of the era, Roosevelt believed in social evolution; as an authority on biology he paid special attention to the issue. He saw the different races as having reached different levels of civilization, with whites thus far having reached a higher level than blacks. Every race, and every individual, was capable of unlimited improvement, Roosevelt felt. Furthermore, a new "race" (in the cultural sense, not biological) had emerged on the American frontier, the "American race," and it was quite distinct from other ethnic groups, such as the Anglo-Saxons. Roosevelt identified himself as Dutch, not Anglo-Saxon. After criticism of Washington's invitation to the White House, Roosevelt seemed to wilt publicly on the cause of racial equality. In 1906, he approved the dishonorable discharges of three companies of black soldiers who all refused his direct order to testify regarding their actions during a violent episode in Brownsville, Texas

, known as the Brownsville Raid.

In 1905, Roosevelt wanted the city of San Francisco to allow 93 Japanese students to attend public schools with whites; they were assigned to the public school for Chinese students, which Japan had protested. Roosevelt threatened a lawsuit. Finally a compromise was reached where the School Board would allow the Japanese students to attend public school with whites and Roosevelt would ask Japan to stop issuing passports to laborers. By the "Gentleman's Agreement," Japan did stop issuing passports to unskilled workers.

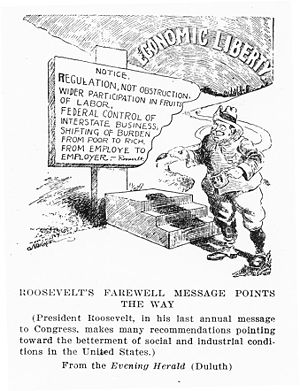

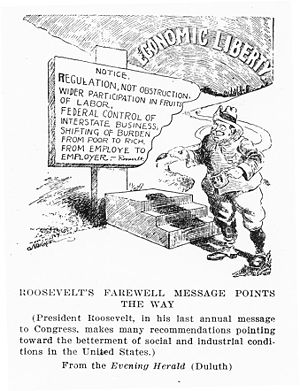

None of his agenda was enacted, and Roosevelt carried over the ideas into the 1912 campaign. Roosevelt's increasingly radical stance proved popular in the Midwest and Pacific Coast, and among farmers, teachers, clergymen, clerical workers and some proprietors, but appeared as divisive and unnecessary to eastern Republicans, corporate executives, lawyers, party workers, and Congressmen.

None of his agenda was enacted, and Roosevelt carried over the ideas into the 1912 campaign. Roosevelt's increasingly radical stance proved popular in the Midwest and Pacific Coast, and among farmers, teachers, clergymen, clerical workers and some proprietors, but appeared as divisive and unnecessary to eastern Republicans, corporate executives, lawyers, party workers, and Congressmen.

Roosevelt's move left allowed Senator Nelson Aldrich to tighten his control of Congress. In 1908, Aldrich introduced the constitutional amendment to establish an income tax

. The same year he wrote the Aldrich-Vreeland Act

which created the National Monetary Commission

, which he directed. It made an in-depth study of central banking in Europe—which was far more effective than America in that regard. Aldrich's dramatic proposals for comprehensive reform became the Federal Reserve in 1913.

He wanted the president to have little power because the president wasn't going to be in office for long.

Roosevelt had traveled widely and was well informed on international affairs, as well as military and naval affairs around the world. He was determined to make America a great world power while avoiding war.

Roosevelt had traveled widely and was well informed on international affairs, as well as military and naval affairs around the world. He was determined to make America a great world power while avoiding war.

of 1898 was fought mostly by temporary volunteers and state national guard units. It demonstrated that more effective control over the department and bureaus was necessary.

Roosevelt gave strong support to the reforms proposed by his War Secretary Elihu Root

(1899–1904), who wanted a uniformed chief of staff as general manager and a European-type general staff for planning. Root was stymied by General Nelson A. Miles

but did succeed in enlarging West Point

and establishing the U.S. Army War College

as well as the General Staff. Root changed the procedures for promotions and organized schools for the special branches of the service. He also devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line. Root was concerned about the new territories acquired after the Spanish-American War

and worked out the procedures for turning Cuba over to the Cubans, wrote the charter of government for the Philippines, and eliminated tariffs on goods imported to the United States from Puerto Rico.

and an advocate of his doctrine of Sea Power, worked to build the Navy into a force befitting a major world power. He sent the Great White Fleet

(named after its gleaming white paint) on an around-the-world cruise, in 1908-09. By 1904, the United States had the fifth largest Navy in the world; by 1907, it had the third largest. As a tribute to him, several Navy warships have been named after Roosevelt over the years, including a Nimitz class supercarrier

.

In late 1904, following the Venezuela Crisis of 1902-1903, Roosevelt announced his Roosevelt Corollary

In late 1904, following the Venezuela Crisis of 1902-1903, Roosevelt announced his Roosevelt Corollary

to the Monroe Doctrine

. It stated that the U.S. would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries if they defaulted on their debts to European creditors and, in effect, guarantee their debts, making it unnecessary for European powers to intervene to collect unpaid debts. In the case of Venezuela

's default, Germany

had threatened to seize the customs houses in her ports. Thus, Roosevelt's pronouncement was especially meant as a warning to Germany, and had the result of promoting peace in the region, as the Germans decided to not intervene directly in Venezuela and in other countries.

to meet in a peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire

, starting on August 5. His persistent and effective mediation led to the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth

on September 5, ending the war. For his efforts, Roosevelt was awarded the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize

.

of 1905; it was a conversation that did not produce an agreement).

to form a nation independent from Colombia

, after that nation refused the American terms for the building of a canal across the isthmus. Roosevelt dispatched navy vessels to the area to apply political pressure on the Colombian government, allowing the Panamanian rebels to secede without much opposition. The new nation of Panama sold a canal zone

to the United States for $10 million and a steadily increasing yearly sum. Roosevelt felt that a passage through the Isthmus of Panama

was vital to protect American interests and to create a strong and cohesive United States Navy

. The resulting Panama Canal

was completed in 1914 and revolutionized world travel and commerce.

, Roosevelt convinced France

to attend an international conference

to resolve the First Moroccan Crisis

over the degree of influence of European powers in Morocco

. France was positioning itself to dominate Morocco, which angered Germany. Germany was annoyed that it had no presence in North Africa

, and hinted darkly that a failure to adjust the crisis might lead to war between Germany and France. The Sultan of Morocco was a weak figure who could not control his own cities. The conference was held in the city of Algeciras

, Spain

, and 13 nations attended. The American delegate was Henry White

, who mediated between France and Germany. The main issue was control of the police forces in the Moroccan cities, and Germany, with a weak diplomatic delegation, found itself in a decided minority. Roosevelt secretly supported France and did not want Germany to gain a more powerful position in Morocco. Roosevelt cooperated closely with the French ambassador, while gaining from the Germans a promise that Roosevelt would have a decisive role. Agreement was reached on April 7, 1906, which slightly reduced French influence by reaffirming the independence of the Sultan and the economic independence and freedom of operations of all European powers. Germany gained nothing of importance but was mollified and stopped threatening war.

independent, with perhaps some kind of international guarantee for the preservation of order, or with some warning on our part that if they did not keep order we would have to interfere again." By then the President and his foreign policy advisers turned away from Asian issues to concentrate on Latin America, and Roosevelt redirected Philippine policy to prepare the islands to become the first Western colony in Asia to achieve self government.

:

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity...

was the 26th (1901–1909) President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

. He had been the 25th Vice President

Vice President of the United States

The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term...

before becoming President upon the assassination of President William McKinley

William McKinley

William McKinley, Jr. was the 25th President of the United States . He is best known for winning fiercely fought elections, while supporting the gold standard and high tariffs; he succeeded in forging a Republican coalition that for the most part dominated national politics until the 1930s...

. Owing to his charismatic personality and reformist policies, which he called the "Square Deal

Square Deal

The Square Deal was President Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program formed upon three basic ideas: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection...

", Roosevelt is considered one of the ablest presidents and an icon of the Progressive Era

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political...

.

Overview

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second most populous city in the state of New York, after New York City. Located in Western New York on the eastern shores of Lake Erie and at the head of the Niagara River across from Fort Erie, Ontario, Buffalo is the seat of Erie County and the principal city of the...

on September 6, 1901, and died on September 14, putting Roosevelt into the presidency. A few weeks short of his 43rd birthday, he was the youngest person to hold the office. Roosevelt continued McKinley's cabinet and promised to continue McKinley's policies. One of his first notable acts as President was to deliver a 20,000-word address to Congress on December 3, 1901, asking it to curb the power of large corporation

Corporation

A corporation is created under the laws of a state as a separate legal entity that has privileges and liabilities that are distinct from those of its members. There are many different forms of corporations, most of which are used to conduct business. Early corporations were established by charter...

s (called "trusts") "within reasonable limits." For his aggressive attacks on trusts over his two terms he was called a "trust-buster."

Roosevelt relished the Presidency and seemed to be everywhere at once. He took Cabinet

United States Cabinet

The Cabinet of the United States is composed of the most senior appointed officers of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States, which are generally the heads of the federal executive departments...

members and friends on long, fast-paced hikes, boxed in the state rooms of the White House, romped with his children, and read voraciously. He was permanently blinded in one eye during one of his boxing bouts.

In 1904, Roosevelt ran for President in his own right and won in a landslide victory.

Building on McKinley's effective use of the press, Roosevelt made the White House

White House

The White House is the official residence and principal workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., the house was designed by Irish-born James Hoban, and built between 1792 and 1800 of white-painted Aquia sandstone in the Neoclassical...

the center of news every day, providing interviews and photo opportunities. He accomplished this after noticing the White House reporters huddled outside in the rain one day; he gave them their own room inside, effectively inventing the presidential press briefing. The grateful press, with unprecedented access to the White House, rewarded Roosevelt with ample coverage. This was helped by Roosevelt's practice of screening out reporters he didn't like.

Progressivism

Determined to create what he called a "Square DealSquare Deal

The Square Deal was President Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program formed upon three basic ideas: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection...

" between business and labor, Roosevelt pushed several pieces of progressive legislation through Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

.

Progressivism in the United States

Progressivism in the United States

Progressivism in the United States is a broadly based reform movement that reached its height early in the 20th century and is generally considered to be middle class and reformist in nature. It arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization, such as the growth of large...

was the most powerful political force of the day, and in the first dozen years of the century Roosevelt was its most articulate spokesman. Progressivism meant expertise, and the use of science, engineering, technology and the new social sciences to identify the nation's problems, and identify ways to eliminate waste and inefficiency and to promote modernization. Roosevelt, trained as a biologist, identified himself and his programs with the mystique of science. The other side of Progressivism was a burning hatred of corruption and a fear of powerful and dangerous forces, such as political machines, the corrupt segment of labor unions and especially the new large corporations — called "trusts" — which seemed to have emerged overnight. Roosevelt, the former deputy sheriff on the Dakota frontier, and police commissioner of New York City, was keenly interested in a law and order. Indeed, he was the first president with significant law enforcement experience, and his moralistic determination set the tone of national politics.

Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902

A national emergency was averted in 1902 when Roosevelt found a compromise to the Anthracite coal strike that threatened the heating supplies of most homes. Roosevelt forced an end to the strike when he threatened to use the United States Army to mine the coal and seize the mines. By bringing representatives of both parties together the president was able to facilitate the negotiations, he convinced both the miners and owners to accept the findings of a commission.The labor union and the owners both reached an agreement after this episode where the labor union agreed to not be the official bargainer for the workers and the workers got better pay and fewer hours.'

Trust busting

Elkins Act

The Elkins Act is a 1903 United States federal law that amended the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The Elkins Act authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to impose heavy fines on railroads that offered rebates, and upon the shippers that accepted these rebates. The railroad companies were...

(1903) and especially the Hepburn Act

Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to set maximum railroad rates. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. In addition, the ICC could view the railroads' financial records, a task simplified by...

of 1906, which had the effect of favoring merchants over the railroads. Under his leadership, the Attorney General brought forty-four suits against businesses that were claimed to be monopolies, most notably J.P. Morgan's Northern Securities Company

Northern Securities Company

The Northern Securities Company was an important United States railroad trust formed in 1902 by E. H. Harriman, James J. Hill, J.P. Morgan, J. D. Rockefeller, and their associates. The company controlled the Northern Pacific Railway, Great Northern Railway, Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad,...

, a huge railroad combination, and J. D. Rockefeller

John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller was an American oil industrialist, investor, and philanthropist. He was the founder of the Standard Oil Company, which dominated the oil industry and was the first great U.S. business trust. Rockefeller revolutionized the petroleum industry and defined the structure of...

's Standard Oil Company. Both were successful, with Standard Oil broken into over 30 smaller companies that eventually competed with one another. To raise the visibility of labor and management issues, he established a new federal Department of Commerce and Labor

United States Department of Commerce and Labor

The United States Department of Commerce and Labor was a short-lived Cabinet department of the United States government, which was concerned with Business.It was created on February 14, 1903...

.

Pure Food and Drugs

In response to public clamor, Roosevelt pushed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug ActPure Food and Drug Act

The Pure Food and Drug Act of June 30, 1906, is a United States federal law that provided federal inspection of meat products and forbade the manufacture, sale, or transportation of adulterated food products and poisonous patent medicines...

of 1906, as well as the Meat Inspection Act

Meat Inspection Act

The Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906 was a United States Congress Act that worked to prevent adulterated or misbranded meat and meat products from being sold as food and to ensure that meat and meat products are slaughtered and processed under sanitary conditions. These requirements also apply...

of 1906. These laws provided for labeling of foods and drugs, inspection of livestock and mandated sanitary conditions at meatpacking plants. Congress replaced Roosevelt's proposals with a version supported by the major meatpackers who worried about the overseas markets, and did not want small unsanitary plants undercutting their domestic market.

Railroad regulation

Roosevelt firmly believed that "The Government must in increasing degree supervise and regulate the workings of the railways engaged in interstate commerce." Inaction was a danger, he argued, "Such increased supervision is the only alternative to an increase of the present evils on the one hand or a still more radical policy on the other." (Annual Message Dec 1904) The Elkins ActElkins Act

The Elkins Act is a 1903 United States federal law that amended the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The Elkins Act authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to impose heavy fines on railroads that offered rebates, and upon the shippers that accepted these rebates. The railroad companies were...

of 1903 was the Administration's first effort at the regulation of railroad rates; it proved ineffective in practice. Roosevelt agreed with the shipping interests who wanted lower rates and a stronger Interstate Commerce Commission

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission was a regulatory body in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers, including...

to enforce them. As Roosevelt told Congress, "Above all else, we must strive to keep the highways of commerce open to all on equal terms; and to do this it is necessary to put a complete stop to all rebates." Politically this was action on behalf of shippers; it was assumed that the railroads would always be powerful and no amount of regulation would seriously weaken them. (No one dreamed of a vast highway system carrying millions of trucks and automobiles.)

Roosevelt encountered opposition in his party, led in the Senate by Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, the party leader; Joseph B. Foraker

Joseph B. Foraker

Joseph Benson Foraker was a Republican politician from Ohio. He served as the 37th Governor of Ohio from 1886 to 1890.-Early life:...

of Ohio; Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew was an attorney for Cornelius Vanderbilt's railroad interests, president of the New York Central Railroad System, and a United States Senator from New York from 1899 to 1911.- Biography:...

of New York (the president of the New York Central Railroad),

Stephen Elkins of West Virginia, Philander Knox of Pennsylvania (formerly Roosevelt's Attorney General), and one of his closest personal friends Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot "Slim" Lodge was an American Republican Senator and historian from Massachusetts. He had the role of Senate Majority leader. He is best known for his positions on Meek policy, especially his battle with President Woodrow Wilson in 1919 over the Treaty of Versailles...

of Massachusetts. Roosevelt therefore planned to rely on a group of Midwestern Republicans, especially William Allison

William B. Allison

William Boyd Allison was an early leader of the Iowa Republican Party, who represented northeastern Iowa for four consecutive terms in the U.S. House before representing his state for six consecutive terms in the U.S. Senate...

of Iowa. He wanted to avoid having to collaborate with Ben Tillman of South Carolina, whom he considered "one of the foulest and rottenest demagogues in the whole country." In the end Roosevelt convinced the conservatives that the courts would protect the railroads' interests, and he carried the bill without Tillman.

The Hepburn Act

Hepburn Act

The Hepburn Act is a 1906 United States federal law that gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to set maximum railroad rates. This led to the discontinuation of free passes to loyal shippers. In addition, the ICC could view the railroads' financial records, a task simplified by...

of 1906 gave the Interstate Commerce Commission

Interstate Commerce Commission

The Interstate Commerce Commission was a regulatory body in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers, including...

(ICC) the power to set maximum railroad rates and stopped free passes given to friends of the railroad. In addition, the ICC could view the railroads' financial records, a task simplified by standardized booking systems. For any railroad that resisted, the ICC's conditions would be in effect until the outcome of litigation said otherwise. By the Hepburn Act, the ICC's authority was extended to cover bridges, terminals, ferries, sleeping cars, express companies and oil pipelines. Along with the Elkins Act of 1903, the Hepburn Act accomplished one of Roosevelt's major goals, railroad regulation. The main beneficiaries were the merchants who received lower shipping rates.

Conservation

Roosevelt was a prominent conservationistConservationist

Conservationists are proponents or advocates of conservation. They advocate for the protection of all the species in an ecosystem with a strong focus on the natural environment...

, putting the issue high on the national agenda. He worked with all the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter, Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot was the first Chief of the United States Forest Service and the 28th Governor of Pennsylvania...

. Roosevelt was deeply committed to conserving natural resources, and is considered to be the nation's first conservation

Conservation biology

Conservation biology is the scientific study of the nature and status of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction...

President. He encouraged the Newlands Reclamation Act

Newlands Reclamation Act

The Reclamation Act of 1902 is a United States federal law that funded irrigation projects for the arid lands of 20 states in the American West....

of 1902 to promote federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed 230 million acres (360,000 mi² or 930,000 km²) under federal protection. Roosevelt set aside more Federal land land national park

National park

A national park is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual nations designate their own national parks differently A national park is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or...

s and nature preserves than all of his predecessors combined.

Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service

United States Forest Service

The United States Forest Service is an agency of the United States Department of Agriculture that administers the nation's 155 national forests and 20 national grasslands, which encompass...

, signed into law the creation of five National Parks, and signed the 1906 Antiquities Act

Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act of 1906, officially An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities , is an act passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt on June 8, 1906, giving the President of the United States authority to, by executive order, restrict the use of...

, under which he proclaimed 18 new U.S. National Monument

U.S. National Monument

A National Monument in the United States is a protected area that is similar to a National Park except that the President of the United States can quickly declare an area of the United States to be a National Monument without the approval of Congress. National monuments receive less funding and...

s. He also established the first 51 Bird Reserve

Bird Reserve

A bird reserve is a wildlife refuge designed to protect bird species. Like other wildlife refuges, the main goal of a reserve is to prevent species from becoming endangered or extinct. Typically, bird species in a reserve are protected from hunting and habitat destruction...

s, four Game Preserves, and 150 National Forests

United States National Forest

National Forest is a classification of federal lands in the United States.National Forests are largely forest and woodland areas owned by the federal government and managed by the United States Forest Service, part of the United States Department of Agriculture. Land management of these areas...

, including Shoshone National Forest

Shoshone National Forest

Shoshone National Forest is the first federally protected National Forest in the United States and covers nearly 2.5 million acres in the state of Wyoming. Originally a part of the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, the forest was created by an act of Congress and signed into law by U.S....

, the nation's first. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately 230000000 acres (930,777.8 km²).

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot was the first Chief of the United States Forest Service and the 28th Governor of Pennsylvania...

had been appointed by McKinley as chief of Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. In 1905, his department gained control of the national forest reserves. Pinchot promoted private use (for a fee) under federal supervision. In 1907, Roosevelt designated 16 million acres (65,000 km²) of new national forests just minutes before a deadline.

In May 1908, Roosevelt sponsored the Conference of Governors

Conference of Governors

The Conference of Governors was held in the White House May 13-15, 1908 under the sponsorship of President Theodore Roosevelt. Gifford Pinchot, at that time Chief Forester of the U.S., was the primary mover of the conference....

held in the White House, with a focus on natural resources and their most efficient use. Roosevelt delivered the opening address: "Conservation as a National Duty."

In 1903 Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with John Muir

John Muir

John Muir was a Scottish-born American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness in the United States. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have been read by millions...

, who had a very different view of conservation, and tried to minimize commercial use of water resources and forests. Working through the Sierra Club

Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is the oldest, largest, and most influential grassroots environmental organization in the United States. It was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by the conservationist and preservationist John Muir, who became its first president...

he founded, Muir succeeded in 1905 in having Congress transfer the Mariposa Grove

Mariposa Grove

Mariposa Grove is a sequoia grove located near Wawona, California, United States, in the southernmost part of Yosemite National Park. It is the largest grove of Giant Sequoias in the park, with several hundred mature examples of the tree...

and Yosemite Valley to the National Park Service

National Park Service

The National Park Service is the U.S. federal agency that manages all national parks, many national monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations...

. While Muir wanted nature preserved for the sake of pure beauty, Roosevelt subscribed to Pinchot's formulation, "to make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees."

Civil Rights

Although Roosevelt did some work improving race relations, he, like most leaders of the Progressive EraProgressive Era

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political...

, lacked initiative on most racial issues. Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and political leader. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915...

, the most important black leader of the day, was the first African American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

to be invited to dinner, on October 16, 1901, at the White House, where he discussed politics and racism

Racism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

with Roosevelt. News of the dinner reached the press two days later. The white public outcry following the dinner was so strong, especially from the Southern states, that Roosevelt never repeated the experiment. Roosevelt was reluctant to use federal authority to enforce the 15th Amendment

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing voting rights to African Americans.

Discrimination

Discrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

, and appointed many blacks to lower-level Federal offices, and wrote fondly of the "Buffalo Soldiers," who had fought beside his Rough Riders

Rough Riders

The Rough Riders is the name bestowed on the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish-American War and the only one of the three to see action. The United States Army was weakened and left with little manpower after the American Civil War...

at the Battle of San Juan Hill

Battle of San Juan Hill

The Battle of San Juan Hill , also known as the battle for the San Juan Heights, was a decisive battle of the Spanish-American War. The San Juan heights was a north-south running elevation about two kilometers east of Santiago de Cuba. The names San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill were names given by the...

in Cuba in July 1898. However, soon after returning from San Juan Hill, Roosevelt changed his story concerning African American Soldiers and their conduct in battle saying "Under the strain the colored infantrymen (who had none of their white officers) began to get a little uneasy and drift to the rear… This I could not allow." Roosevelt opposed school segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

, having ended the practice in New York State during his governorship. Roosevelt rejected anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

—he was the first to appoint a Jew, Oscar S. Straus, to the cabinet.

Like most intellectuals of the era, Roosevelt believed in social evolution; as an authority on biology he paid special attention to the issue. He saw the different races as having reached different levels of civilization, with whites thus far having reached a higher level than blacks. Every race, and every individual, was capable of unlimited improvement, Roosevelt felt. Furthermore, a new "race" (in the cultural sense, not biological) had emerged on the American frontier, the "American race," and it was quite distinct from other ethnic groups, such as the Anglo-Saxons. Roosevelt identified himself as Dutch, not Anglo-Saxon. After criticism of Washington's invitation to the White House, Roosevelt seemed to wilt publicly on the cause of racial equality. In 1906, he approved the dishonorable discharges of three companies of black soldiers who all refused his direct order to testify regarding their actions during a violent episode in Brownsville, Texas

Brownsville, Texas

Brownsville is a city in the southernmost tip of the state of Texas, in the United States. It is located on the northern bank of the Rio Grande, directly north and across the border from Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Brownsville is the 16th largest city in the state of Texas with a population of...

, known as the Brownsville Raid.

In 1905, Roosevelt wanted the city of San Francisco to allow 93 Japanese students to attend public schools with whites; they were assigned to the public school for Chinese students, which Japan had protested. Roosevelt threatened a lawsuit. Finally a compromise was reached where the School Board would allow the Japanese students to attend public school with whites and Roosevelt would ask Japan to stop issuing passports to laborers. By the "Gentleman's Agreement," Japan did stop issuing passports to unskilled workers.

Radical shift, 1907–1908

By 1907–08, his last two years in office, Roosevelt was increasingly distrustful of big business, despite its close ties to the Republican party in every large state. Public opinion had been shifting to the left after a series of scandals, and big business was in bad odor. Abandoning his earlier cautious approach toward big business, Roosevelt freely lambasted his conservative critics and called on Congress to enact a series of radical new laws — the Square Deal — that would regulate the economy. He wanted a national incorporation law (all corporations had state charters, which varied greatly state by state), a federal income tax and inheritance tax (both targeted on the rich), limits on the use of court injunctions against labor unions during strikes (injunctions were a powerful weapon that mostly helped business), an employee liability law for industrial injuries (preempting state laws), an eight-hour law for federal employees, a postal savings system (to provide competition for local banks), and, finally, campaign reform laws.

Roosevelt's move left allowed Senator Nelson Aldrich to tighten his control of Congress. In 1908, Aldrich introduced the constitutional amendment to establish an income tax

Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution allows the Congress to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states or basing it on Census results...

. The same year he wrote the Aldrich-Vreeland Act

Aldrich-Vreeland Act

The Aldrich–Vreeland Act was passed in response to the Panic of 1907 and established the National Monetary Commission, which recommended the Federal Reserve Act of 1913....

which created the National Monetary Commission

National Monetary Commission

National Monetary Commission was a study group created by the Aldrich Vreeland Act of 1908. After the Panic of 1907 American bankers turned to Europe for ideas on how to operate a central bank. Senator Nelson Aldrich, Republican leader of the Senate, personally led a team of experts to major...

, which he directed. It made an in-depth study of central banking in Europe—which was far more effective than America in that regard. Aldrich's dramatic proposals for comprehensive reform became the Federal Reserve in 1913.

He wanted the president to have little power because the president wasn't going to be in office for long.

Foreign policy

Army

The U.S. Army, with 39,000 men in 1890 was the smallest and least powerful army of any major power in the late 19th century. By contrast, France had 542,000. The Spanish-American WarSpanish-American War

The Spanish–American War was a conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States, effectively the result of American intervention in the ongoing Cuban War of Independence...

of 1898 was fought mostly by temporary volunteers and state national guard units. It demonstrated that more effective control over the department and bureaus was necessary.

Roosevelt gave strong support to the reforms proposed by his War Secretary Elihu Root

Elihu Root

Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C...

(1899–1904), who wanted a uniformed chief of staff as general manager and a European-type general staff for planning. Root was stymied by General Nelson A. Miles

Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles was a United States soldier who served in the American Civil War, Indian Wars, and the Spanish-American War.-Early life:Miles was born in Westminster, Massachusetts, on his family's farm...

but did succeed in enlarging West Point

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy at West Point is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located at West Point, New York. The academy sits on scenic high ground overlooking the Hudson River, north of New York City...

and establishing the U.S. Army War College

U.S. Army War College

The United States Army War College is a United States Army school located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, on the 500 acre campus of the historic Carlisle Barracks...

as well as the General Staff. Root changed the procedures for promotions and organized schools for the special branches of the service. He also devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line. Root was concerned about the new territories acquired after the Spanish-American War

Spanish-American War

The Spanish–American War was a conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States, effectively the result of American intervention in the ongoing Cuban War of Independence...

and worked out the procedures for turning Cuba over to the Cubans, wrote the charter of government for the Philippines, and eliminated tariffs on goods imported to the United States from Puerto Rico.

Navy

Roosevelt, a friend of Alfred Thayer MahanAlfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan was a United States Navy flag officer, geostrategist, and historian, who has been called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His concept of "sea power" was based on the idea that countries with greater naval power will have greater worldwide...

and an advocate of his doctrine of Sea Power, worked to build the Navy into a force befitting a major world power. He sent the Great White Fleet

Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the United States Navy battle fleet that completed a circumnavigation of the globe from 16 December 1907 to 22 February 1909 by order of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. It consisted of 16 battleships divided into two squadrons, along with...

(named after its gleaming white paint) on an around-the-world cruise, in 1908-09. By 1904, the United States had the fifth largest Navy in the world; by 1907, it had the third largest. As a tribute to him, several Navy warships have been named after Roosevelt over the years, including a Nimitz class supercarrier

Supercarrier

Supercarrier is an unofficial descriptive term for the largest type of aircraft carrier, usually displacing over 70,000 long tons.Supercarrier is an unofficial descriptive term for the largest type of aircraft carrier, usually displacing over 70,000 long tons.Supercarrier is an unofficial...

.

Roosevelt Corollary

Roosevelt Corollary

-Background:In late 1902, Britain, Germany, and Italy implemented a naval blockade of several months against Venezuela because of President Cipriano Castro's refusal to pay foreign debts and damages suffered by European citizens in a recent Venezuelan civil war. The incident was called the...

to the Monroe Doctrine

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a policy of the United States introduced on December 2, 1823. It stated that further efforts by European nations to colonize land or interfere with states in North or South America would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring U.S. intervention...

. It stated that the U.S. would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries if they defaulted on their debts to European creditors and, in effect, guarantee their debts, making it unnecessary for European powers to intervene to collect unpaid debts. In the case of Venezuela

Venezuela

Venezuela , officially called the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela , is a tropical country on the northern coast of South America. It borders Colombia to the west, Guyana to the east, and Brazil to the south...

's default, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

had threatened to seize the customs houses in her ports. Thus, Roosevelt's pronouncement was especially meant as a warning to Germany, and had the result of promoting peace in the region, as the Germans decided to not intervene directly in Venezuela and in other countries.

Ending the Russo-Japanese War

In the summer of 1905, Roosevelt persuaded the parties in the Russo-Japanese WarRusso-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War was "the first great war of the 20th century." It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea...

to meet in a peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire in the United States. It is the largest city but only the fourth-largest community in the county, with a population of 21,233 at the 2010 census...

, starting on August 5. His persistent and effective mediation led to the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth

Treaty of Portsmouth

The Treaty of Portsmouth formally ended the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War. It was signed on September 5, 1905 after negotiations at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine in the USA.-Negotiations:...

on September 5, ending the war. For his efforts, Roosevelt was awarded the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize

Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes bequeathed by the Swedish industrialist and inventor Alfred Nobel.-Background:According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who...

.

Korea

Roosevelt saw Japan as the rising power in Asia, in terms of military strength and economic modernization. He viewed Korea as a backward nation and did not object to Japanese moves to control the strategic Korean peninsula. With the withdrawal of the American legation from Seoul and the refusal of the Secretary of State to receive a Korean protest mission, the Americans signaled they would not intervene militarily to stop Japan's planned takeover of Korea. (There is a myth regarding a so-called Taft-Katsura agreementTaft-Katsura Agreement

The Taft–Katsura Agreement was a set of notes taken during conversations between United States Secretary of War William Howard Taft and Prime Minister of Japan Katsura Tarō on 29 July 1905...

of 1905; it was a conversation that did not produce an agreement).

Panama Canal

In 1903, Roosevelt encouraged the local political class in PanamaPanama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

to form a nation independent from Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

, after that nation refused the American terms for the building of a canal across the isthmus. Roosevelt dispatched navy vessels to the area to apply political pressure on the Colombian government, allowing the Panamanian rebels to secede without much opposition. The new nation of Panama sold a canal zone

Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone was a unorganized U.S. territory located within the Republic of Panama, consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending 5 miles on each side of the centerline, but excluding Panama City and Colón, which otherwise would have been partly within the limits of...

to the United States for $10 million and a steadily increasing yearly sum. Roosevelt felt that a passage through the Isthmus of Panama

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country of Panama and the Panama Canal...

was vital to protect American interests and to create a strong and cohesive United States Navy

United States Navy

The United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

. The resulting Panama Canal

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

was completed in 1914 and revolutionized world travel and commerce.

Algeciras Conference

In 1906, at the request of Kaiser Wilhelm II of GermanyGerman Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, Roosevelt convinced France

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

to attend an international conference

Algeciras Conference

The Algeciras Conference of 1906 took place in Algeciras, Spain, and lasted from January 16 to April 7. The purpose of the conference was to find a solution to the First Moroccan Crisis between France and Germany, which arose as Germany attempted to prevent France from establishing a protectorate...

to resolve the First Moroccan Crisis

First Moroccan Crisis

The First Moroccan Crisis was the international crisis over the international status of Morocco between March 1905 and May 1906. Germany resented France's increasing dominance of Morocco, and insisted on an open door policy that would allow German business access to its market...

over the degree of influence of European powers in Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

. France was positioning itself to dominate Morocco, which angered Germany. Germany was annoyed that it had no presence in North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

, and hinted darkly that a failure to adjust the crisis might lead to war between Germany and France. The Sultan of Morocco was a weak figure who could not control his own cities. The conference was held in the city of Algeciras

Algeciras

Algeciras is a port city in the south of Spain, and is the largest city on the Bay of Gibraltar . Port of Algeciras is one of the largest ports in Europe and in the world in three categories: container,...

, Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, and 13 nations attended. The American delegate was Henry White

Henry White (diplomat)

Henry White was a prominent U.S. diplomat during the 1890s and 1900s, and one of the signers of the Treaty of Versailles....

, who mediated between France and Germany. The main issue was control of the police forces in the Moroccan cities, and Germany, with a weak diplomatic delegation, found itself in a decided minority. Roosevelt secretly supported France and did not want Germany to gain a more powerful position in Morocco. Roosevelt cooperated closely with the French ambassador, while gaining from the Germans a promise that Roosevelt would have a decisive role. Agreement was reached on April 7, 1906, which slightly reduced French influence by reaffirming the independence of the Sultan and the economic independence and freedom of operations of all European powers. Germany gained nothing of importance but was mollified and stopped threatening war.

Philippines

After the official end of Aguinaldo's insurrection in 1902, the insurgents accepted American rule and peace prevailed, except in some remote islands under Muslim control. Roosevelt continued the McKinley policies of removing the Catholic friars (with compensation to the Pope), upgrading the infrastructure, introducing public health programs, and launching a program of economic and social modernization. The enthusiasm shown in 1898-99 for colonies cooled off, and Roosevelt saw the islands as "our heel of Achilles." He told Taft in 1907, "I should be glad to see the islands madeindependent, with perhaps some kind of international guarantee for the preservation of order, or with some warning on our part that if they did not keep order we would have to interfere again." By then the President and his foreign policy advisers turned away from Asian issues to concentrate on Latin America, and Roosevelt redirected Philippine policy to prepare the islands to become the first Western colony in Asia to achieve self government.

Administration and Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President President of the United States The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces.... |

Theodore Roosevelt Theodore Roosevelt Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States . He is noted for his exuberant personality, range of interests and achievements, and his leadership of the Progressive Movement, as well as his "cowboy" persona and robust masculinity... |

1901–1909 |

| Vice President Vice President of the United States The Vice President of the United States is the holder of a public office created by the United States Constitution. The Vice President, together with the President of the United States, is indirectly elected by the people, through the Electoral College, to a four-year term... |

Charles Fairbanks | 1905–1909 |

| Secretary of State United States Secretary of State The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence... |

John Hay John Hay John Milton Hay was an American statesman, diplomat, author, journalist, and private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln.-Early life:... |

1901–1905 |

| Elihu Root Elihu Root Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C... |

1905–1909 | |

| Robert Bacon Robert Bacon Robert Bacon was an American statesman and diplomat. He served as United States Secretary of State from January to March 1909.-Biography:... |

1909 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury United States Secretary of the Treasury The Secretary of the Treasury of the United States is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, which is concerned with financial and monetary matters, and, until 2003, also with some issues of national security and defense. This position in the Federal Government of the United... |

Lyman J. Gage Lyman J. Gage Lyman Judson Gage was an American financier and Presidential Cabinet officer.He was born at DeRuyter, New York, educated at an academy at Rome, New York, and at the age of 17 he became a bank clerk... |

1901–1902 |

| Leslie M. Shaw | 1902–1907 | |

| George B. Cortelyou George B. Cortelyou George Bruce Cortelyou was an American Presidential Cabinet secretary of the early 20th century.-Early life:... |

1907–1909 | |

| Secretary of War United States Secretary of War The Secretary of War was a member of the United States President's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War," was appointed to serve the Congress of the Confederation under the Articles of Confederation... |

Elihu Root Elihu Root Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C... |

1901–1904 |

| William Howard Taft William Howard Taft William Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States and later the tenth Chief Justice of the United States... |

1904–1908 | |

| Luke E. Wright | 1908–1909 | |

| Attorney General | Philander C. Knox Philander C. Knox Philander Chase Knox was an American lawyer and politician who served as United States Attorney General , a Senator from Pennsylvania and Secretary of State .... |

1901–1904 |

| William H. Moody | 1904–1906 | |

| Charles J. Bonaparte | 1906–1909 | |

| Postmaster General | Charles E. Smith Charles Emory Smith Charles Emory Smith was an American journalist and political leader. He was born in Mansfield, Connecticut.... |

1901–1902 |

| Henry C. Payne Henry C. Payne Henry Clay Payne was U.S. Postmaster General from 1902 to 1904 under Pres. Theodore Roosevelt. He died in office and was buried at Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin... |

1902–1904 | |

| Robert J. Wynne | 1904–1905 | |

| George B. Cortelyou George B. Cortelyou George Bruce Cortelyou was an American Presidential Cabinet secretary of the early 20th century.-Early life:... |

1905–1907 | |

| George von L. Meyer | 1907–1909 | |

| Secretary of the Navy United States Secretary of the Navy The Secretary of the Navy of the United States of America is the head of the Department of the Navy, a component organization of the Department of Defense... |

John D. Long | 1901–1902 |

| William H. Moody | 1902–1904 | |

| Paul Morton Paul Morton Paul Morton was a U.S. businessman.- Biography :He served as the Secretary of Navy between 1904 and 1905. Previous to this, he had been vice president of the Santa Fe Railroad... |

1904–1905 | |

| Charles J. Bonaparte | 1905–1906 | |

| Victor H. Metcalf Victor H. Metcalf Victor Howard Metcalf was an American politician; he served in President Theodore Roosevelt's cabinet an Secretary of Commerce and Labor, and then as Secretary of the Navy.-Biography:... |

1906–1908 | |

| Truman H. Newberry | 1908–1909 | |

| Secretary of the Interior United States Secretary of the Interior The United States Secretary of the Interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior.The US Department of the Interior should not be confused with the concept of Ministries of the Interior as used in other countries... |

Ethan A. Hitchcock Ethan A. Hitchcock (Interior) Ethan Allen Hitchcock served under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt as U.S. Secretary of the Interior.-Early life:... |

1901–1907 |

| James Rudolph Garfield James Rudolph Garfield James Rudolph Garfield was an American politician, lawyer and son of President James Abram Garfield and First Lady Lucretia Garfield. He was Secretary of the Interior during Theodore Roosevelt's administration.... |

1907–1909 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture United States Secretary of Agriculture The United States Secretary of Agriculture is the head of the United States Department of Agriculture. The current secretary is Tom Vilsack, who was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on 20 January 2009. The position carries similar responsibilities to those of agriculture ministers in other... |

James Wilson | 1901–1909 |

| Secretary of Commerce and Labor | George B. Cortelyou George B. Cortelyou George Bruce Cortelyou was an American Presidential Cabinet secretary of the early 20th century.-Early life:... |

1903–1904 |

| Victor H. Metcalf Victor H. Metcalf Victor Howard Metcalf was an American politician; he served in President Theodore Roosevelt's cabinet an Secretary of Commerce and Labor, and then as Secretary of the Navy.-Biography:... |

1904–1906 | |

| Oscar S. Straus Oscar Straus (politician) Oscar Solomon Straus was United States Secretary of Commerce and Labor under President Theodore Roosevelt from 1906 to 1909. Straus was the first Jewish United States Cabinet Secretary. - Biography :... |

1906–1909 | |

Supreme Court appointments

Roosevelt appointed three Justices to the Supreme Court of the United StatesSupreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

:

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932...

- 1902 - William Rufus Day - 1903

- William Henry MoodyWilliam Henry MoodyWilliam Henry Moody was an American politician and jurist, who held positions in all three branches of the Government of the United States.-Biography:...

- 1906

Domestic policy

- Blum, John Morton The Republican Roosevelt. (1954). essays that examine how TR did politics

- Brands, H.W. Theodore Roosevelt (2001) online edition

- Brinkley, Douglas. The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (2009) ch 15-26

- Cooper, John Milton The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. (1983) a dual biography

- Gould, Lewis L. The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. (1991), the major scholarly study

- Harbaugh, William Henry. The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt. (1963)

- Harrison, Robert. Congress, Progressive Reform, and the New American State (2004)

- Keller, Morton, ed., Theodore Roosevelt: A Profile (1967) excerpts from TR and from historians.

- Morris, Edmund Theodore Rex. (2001), unusually well-written biography covers 1901-1909

- Mowry, George. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America, 1900-1912. (1954)

- Pringle, Henry F. Theodore Roosevelt (1932; 2nd ed. 1956) online edition

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Roosevelt-Taft Administration (1922); vol. 8 is a detailed narrative from 1897 to 1909 online edition

- Sanders, Elizabeth. Roots of Reform: Farmers, Workers and the American State, 1877-1917 (1999)

- Wiebe, Robert H. Businessmen and Reform: A Study of the Progressive Movement (1968)

Foreign policy

- Beale Howard K.Howard K. BealeHoward Kennedy Beale was an American historian. He specialized in nineteenth and twentieth-century American history, particularly the Reconstruction Era. He also wrote biographies of Theodore Roosevelt, Edward Bates, and Charles A. Beard. Beale was born in Chicago to Frank A. and Nellie Kennedy...

Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power. (1956). standard history of his foreign policy - Holmes, James R. Theodore Roosevelt and World Order: Police Power in International Relations. 2006. 328 pp.

- Marks III, Frederick W. Velvet on Iron: The Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt (1979)

- David McCullough. The Path between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914 (1977).

- Ricard, Serge. "The Roosevelt Corollary." Presidential Studies Quarterly 2006 36(1): 17-26. Issn: 0360-4918 Fulltext: in Swetswise and Ingenta

Primary sources

- Brands, H.W. ed. The Selected Letters of Theodore Roosevelt. (2001)

- Harbaugh, William ed. The Writings Of Theodore Roosevelt (1967). A one-volume selection of Roosevelt's speeches and essays.

- Hart, Albert Bushnell and Herbert Ronald Ferleger, eds. Theodore Roosevelt Cyclopedia (1941), Roosevelt's opinions on many issues. online at