Polish October

Encyclopedia

Politics of Poland

The politics of Poland take place in the framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the Prime Minister is the head of government of a multi-party system and the President is the head of state....

in the second half of 1956. Some social scientists term it the Polish October Revolution, which, while less dramatic than the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, might have had an even deeper impact on the Eastern Bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

and on the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

's relationship to its communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

satellites in Eastern Europe.

For Poland

People's Republic of Poland

The People's Republic of Poland was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1990. Although the Soviet Union took control of the country immediately after the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944, the name of the state was not changed until eight years later...

, 1956 was a year of transition. The international situation, particularly the deaths of the Soviet Union's leader, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

, and of Polish communist leader Bolesław Bierut, significantly weakened the hardliners' Stalinist faction in Poland. Protests in June by workers in Poznań

Poznan 1956 protests

The Poznań 1956 protests, also known as Poznań 1956 uprising or Poznań June , were the first of several massive protests of the Polish people against the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland...

highlighted the people’s dissatisfaction with their current situation. The events set in motion resulted in the reformers' faction, led by Władysław Gomułka, taking power. After brief but tense negotiations with the Soviet Union, the Soviets gave permission for Gomułka to stay in control, and made several other concessions resulting in wider autonomy

Autonomy

Autonomy is a concept found in moral, political and bioethical philosophy. Within these contexts, it is the capacity of a rational individual to make an informed, un-coerced decision...

for the Polish government. For Polish citizens, this meant the temporary liberalization of life in Poland. Eventually, hopes for full liberalization were proven false, as Gomułka's regime became more oppressive; nonetheless, the era of Stalinization in Poland had ended.

Development

Gomułka's thaw was caused by several factors. The death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and the resulting de-StalinizationHistory of the Soviet Union (1953-1985)

In the USSR, the eleven-year period from the death of Joseph Stalin to the political ouster of Nikita Khrushchev , the national politics were dominated by the Cold War; the ideological U.S.–USSR struggle for the planetary domination of their respective socio–economic systems, and the defense of...

and Khrushchev's Thaw

Khrushchev Thaw

The Khrushchev Thaw refers to the period from the mid 1950s to the early 1960s, when repression and censorship in the Soviet Union were partially reversed and millions of Soviet political prisoners were released from Gulag labor camps, due to Nikita Khrushchev's policies of de-Stalinization and...

prompted debates about fundamental issues throughout the entire Eastern Bloc. Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

's speech, On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

On the Personality Cult and its Consequences

On the Personality Cult and its Consequences was a report, critical of Joseph Stalin, made to the Twentieth Party Congress on February 25, 1956 by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. It is more commonly known as the Secret Speech or the Khrushchev Report...

, had wide implications for the Soviet Union and other communist countries as well.

In Poland, in addition to criticism of the cult of personality

Cult of personality

A cult of personality arises when an individual uses mass media, propaganda, or other methods, to create an idealized and heroic public image, often through unquestioning flattery and praise. Cults of personality are usually associated with dictatorships...

, popular topics of debate centered around the right to steer a more independent course of "local, national socialism" instead of following the Soviet model in every detail. For example, many members of the Polish United Workers' Party

Polish United Workers' Party

The Polish United Workers' Party was the Communist party which governed the People's Republic of Poland from 1948 to 1989. Ideologically it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism.- The Party's Program and Goals :...

(PZPR) criticized Stalin's execution of older Polish communists during the Great Purge

Great Purge

The Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

. Several other factors contributed to the destabilization of Poland. These included the widely publicized defection in 1953 of high-ranking Polish intelligence agent Józef Światło, resulting in the weakening of the Ministry of Public Security of Poland

Ministry of Public Security of Poland

The Ministry of Public Security of Poland was a Polish communist secret police, intelligence and counter-espionage service operating from 1945 to 1954 under Jakub Berman of the Politburo...

(Polish secret police

Secret police

Secret police are a police agency which operates in secrecy and beyond the law to protect the political power of an individual dictator or an authoritarian political regime....

). Also, the unexpected death in Moscow in 1956 of Bolesław Bierut, the PZPR First Secretary

General secretary

-International intergovernmental organizations:-International nongovernmental organizations:-Sports governing bodies:...

(known as the "Stalin of Poland"), led to increased rivalry between various factions of Polish communists and to growing tensions in Polish society, culminating in the Poznań 1956 protests

Poznan 1956 protests

The Poznań 1956 protests, also known as Poznań 1956 uprising or Poznań June , were the first of several massive protests of the Polish people against the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland...

(also known as June '56).

The PZPR Secretariat decided that Khrushchev's speech should have wide circulation in Poland, a unique decision in the Eastern Bloc. Bierut's successors seized on Khrushchev's condemnation of Stalinist policy as a perfect opportunity to prove their reformist, democratic credentials and their willingness to break with the Stalinist legacy. In late March and early April, thousands of Party meetings were held all over Poland, with Politburo and Secretariat blessing. Tens of thousands took part in such meetings. The Secretariat's plan succeeded beyond what they expected. During this period, the whole political atmosphere changed. Tough questions were asked about Polish communists' legitimacy, responsibility for Stalin's crimes, the arrest of the increasingly popular Władysław Gomułka, and issues in Soviet–Polish relations, such as the continued Soviet military presence in Poland

Northern Group of Forces

The Northern Group of Forces was the military formation of the Soviet Army stationed in Poland from the end of Second World War in 1945 until 1993 when they were withdrawn in the aftermath of the fall of Soviet Union...

, the Ribbentrop–Molotov Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

, the Katyn massacre

Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, also known as the Katyn Forest massacre , was a mass execution of Polish nationals carried out by the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs , the Soviet secret police, in April and May 1940. The massacre was prompted by Lavrentiy Beria's proposal to execute all members of...

, and the Soviet failure to support the Warsaw Uprising

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

. A new Party Congress was demanded, as was a greater role for the Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

and a guarantee of personal liberties. Alarmed by the process, the Party Secretariat decided to withhold the speech from the general public.

In June 1956, there was an insurrection in Poznań. The workers rioted to protest shortages of food and consumer goods, bad housing, decline in real income, trade relations with the Soviet Union and poor management of the economy. The Polish government initially responded by branding the rioters "provocateurs

Agent provocateur

Traditionally, an agent provocateur is a person employed by the police or other entity to act undercover to entice or provoke another person to commit an illegal act...

, counterrevolutionaries

Counterrevolutionary

A counter-revolutionary is anyone who opposes a revolution, particularly those who act after a revolution to try to overturn or reverse it, in full or in part...

and imperialist

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

agents". Between 57 and 78 people—mostly protesters—were killed, and hundreds were wounded and arrested. Soon, however, the party hierarchy recognized that the riots had awakened a nationalist movement and reversed their opinion. Wages were raised by 50 percent, and economic and political change was promised.

The Poznań protests, although the largest, were not unique in Poland, where social protest resumed its fury that autumn. On November 18, rioters destroyed the militia headquarters and radio-jamming equipment in Bydgoszcz, and on December 10, a crowd in Szczecin

Szczecin

Szczecin , is the capital city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in Poland. It is the country's seventh-largest city and the largest seaport in Poland on the Baltic Sea. As of June 2009 the population was 406,427....

attacked public buildings, including a prison, the state prosecutor's office, militia headquarters, and the Soviet consulate. People across the country criticized the security police and asked for the dissolution of the public security committee and the punishment of its guiltiest functionaries. Demands were made for the exposure of secret police collaborators, and suspected collaborators were frequently assaulted. In many localities, crowds gathered outside the secret police headquarters, shouted hostile slogans, and broke its windows. Public meetings, demonstrations, and street marches took place in hundreds of towns across Poland. The meetings were usually organized by local Party cells, local authorities, and trade unions. However, official organizers tended to lose control as political content exceeded their original agenda. Crowds often took radical action, in many cases resulting in unrest on the streets and clashes with police and other law-enforcement agencies. Street activity peaked during and immediately after the 19–21 October "VIII Plenum" meeting of the Central Committee of the PZPR, but continued until late in the year.

A concurrent upsurge in religious and clerical sentiment took place. Hymns were sung, and the release of Cardinal Wyszyński and the reinstatement of suppressed bishops were demanded, as were the reintroduction of religious education and of crucifix

Crucifix

A crucifix is an independent image of Jesus on the cross with a representation of Jesus' body, referred to in English as the corpus , as distinct from a cross with no body....

es in classrooms. Nationalism was the cement of mass mobilization and dominated public meetings, during which people sang the national anthem and other patriotic songs, demanded the return of the white eagle to the flag and traditional army uniforms, and attacked Poland's dependence on the Soviet Union and its military. They demanded the return of the eastern territories

Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union

Immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II, the Soviet Union invaded the eastern regions of the Second Polish Republic, which Poles referred to as the "Kresy," and annexed territories totaling 201,015 km² with a population of 13,299,000...

, an explanation for the Katyn massacre, and elimination of the Russian language from the educational curriculum. In the last ten days of October, monuments to the Red Army, despised by Poles, were attacked: red stars were pulled down from roofs of houses, factories and schools; red flags were destroyed; and portraits of Rokosovski

Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Rokossovskiy was a Polish-origin Soviet career officer who was a Marshal of the Soviet Union, as well as Marshal of Poland and Polish Defence Minister, who was famously known for his service in the Eastern Front, where he received high esteem for his outstanding military skill...

, the military commander in charge of operations that drove the Nazi German forces from Poland, were defaced. Attempts were made to force entries into the homes of Soviet citizens, mostly in Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ; is the northwestern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia; Upper Silesia is to the southeast.Throughout its history Lower Silesia has been under the control of the medieval Kingdom of Poland, the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy from 1526...

, home to many Soviet troops. However, unlike the protesters in Hungary and Poznań, activists limited their political demands and behavior, which were not purely anti-communist and anti-system. The communist authorities were not openly and unequivocally challenged, as they had been in June, and anti-Communist slogans that had been prevalent in the June uprising, such as "We want free elections", "Down with Communist dictatorship", or "Down with the Party", were much less prevalent. Party committees were not attacked.

Political change

During the October VIII Plenum meeting, Edward OchabEdward Ochab

Edward Ochab was a Polish Communist politician promoted to the position of the First Secretary of the Communist party in the People's Republic of Poland between 20 March and 21 October 1956, just prior to the Gomułka thaw...

, the Polish Prime Minister, nominated Władysław Gomułka for First Secretary of the Party. Gomułka was a moderate who had previously fallen afoul of the Stalinist hardliners' faction and had been purged in 1951 after losing his battle with Bierut. The decision was made to rehabilitate

Rehabilitation (Soviet)

Rehabilitation in the context of the former Soviet Union, and the Post-Soviet states, was the restoration of a person who was criminally prosecuted without due basis, to the state of acquittal...

Gomułka and elect him to the post of First Secretary of the Central Committee of the PZPR. Gomułka proved to be acceptable to both factions of Polish communists: the reformers, who were arguing for liberalization of the system, and the hardliners, who realized that they needed to compromise. Gomułka insisted that he be given real power to implement reforms. One specific condition he set was that Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, who had mobilized troops against the Poznań workers, be removed from the Polish Politburo

Politburo

Politburo , literally "Political Bureau [of the Central Committee]," is the executive committee for a number of communist political parties.-Marxist-Leninist states:...

and Defense Ministry, to which Ochab agreed. The majority of the Polish leadership, backed by both the army and the Internal Security Corps, brought Gomułka and several associates into the Politburo and designated Gomułka as First Secretary. Untouched by the scandals of Stalinism, Gomułka was acceptable to the Polish masses, but at first was viewed with much suspicion by Moscow.

The Soviet leadership viewed events in Poland with alarm. De-Stalinization was underway in the Soviet Union as well, but the Soviet leadership did not view the democratic reform that the Polish public desired as an acceptable solution. In Moscow, the belief was that any trends towards democracy in one bloc country could lead to the destruction of communism and the ruin of Soviet influence in the region as a whole. Eastern Europe created a fence between Soviet Communism and Western Democracy, and any break in the wall could end Soviet power.

The Soviet Union was not worried solely about the political implications of reform but about the economic implications as well. Economically, the Soviet Union was heavily invested in Poland. The Soviet Union had financed Polish industry and was Poland’s main trading partner. The Soviet Union directed what products Poland manufactured; the Soviets bought the products; and they exported goods to Poland that were no longer produced within the country itself. The Polish and Soviet economies were thus heavily integrated; any reform, whether political or economic, in one of the countries would inevitably have a great impact on the other. Because Poland was inextricably connected to the Soviet Union economically, the thought of an independent Polish economy was unrealistic. The country had been forced to rely on the Soviets for such a long time that breaking away completely would prove disastrous. Thus, both countries held crucial power in different facets. Poland could threaten Soviet strength and power in Eastern Europe politically, and the Soviet Union could essentially destroy the Polish economy. Therefore, any reform in the Polish government would have to concede to some Soviet demands, while the Soviets concurrently would have to concede to a vital partner.

This selection of Gomulka was made despite Moscow's threats to invade Poland if the PZPR picked Gomulka. A high-level delegation of the Soviet Central Committee

Central Committee

Central Committee was the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, whether ruling or non-ruling in the twentieth century and of the surviving, mostly Trotskyist, states in the early twenty first. In such party organizations the...

flew to Poland in an attempt to block Gomułka's return to the party leadership. It was led by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev led the Soviet Union during part of the Cold War. He served as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964, and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, or Premier, from 1958 to 1964...

and included Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Mikoyan

Anastas Ivanovich Mikoyan was an Armenian Old Bolshevik and Soviet statesman during the rules of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev, and Leonid Brezhnev....

, Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin was a prominent Soviet politician, who served as Minister of Defense and Premier of the Soviet Union . The Bulganin beard is named after him.-Early career:...

, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

, Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich was a Soviet politician and administrator and one of the main associates of Joseph Stalin.-Early life:Kaganovich was born in 1893 to Jewish parents in the village of Kabany, Radomyshl uyezd, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire...

, Ivan Konev

Ivan Konev

Ivan Stepanovich Konev , was a Soviet military commander, who led Red Army forces on the Eastern Front during World War II, retook much of Eastern Europe from occupation by the Axis Powers, and helped in the capture of Germany's capital, Berlin....

, and others. The negotiations were tense; both Polish and Soviet troops were put on alert, engaged in 'manoeuvres', and were used as thinly veiled threats. The Polish leadership made it clear that the face of communism had to become more nationalized

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

; no longer could the Soviet Union directly control the Polish people. Here, Khrushchev’s speech worked against him. During Stalinism, the Soviet Union had placed Moscow-friendly Poles, or Russians themselves, in important political positions in Poland; in 1956, even Poland’s defense minister

Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Rokossovskiy was a Polish-origin Soviet career officer who was a Marshal of the Soviet Union, as well as Marshal of Poland and Polish Defence Minister, who was famously known for his service in the Eastern Front, where he received high esteem for his outstanding military skill...

was Russian. After denouncing Stalinism so vehemently in his speech, Khrushchev could not regress to the Stalinist position by forcing more Russians into the Polish leadership.

The Poles, in recognizing the cries of the public, needed to keep the Soviets from direct control but could not raise their demands to a point that endangered their relationships in the bloc. Gomułka demanded increased autonomy and permission to carry out some reforms, but he also reassured the Soviets that the reforms were internal matters and that Poland had no intention of abandoning communism or its treaties with the Soviet Union. The Soviets were also pressured by the Chinese to accommodate the Polish demands and were increasingly distracted by the events in Hungary. Eventually, when Khrushchev was reassured that Gomulka would not alter the basic foundations of Polish communism, he withdrew the invasion threat and agreed to compromise, and Gomułka was confirmed in his new position.

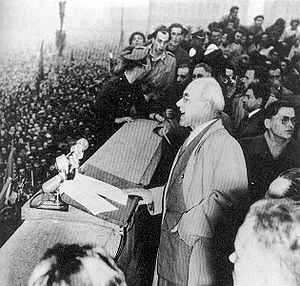

The leadership's stance contributed to the relatively moderate political dimension of social protest in October. Also crucial were the impacts of nationalism and nationalist emotions. They spurred social protest in June but dampened it in October, when the threat of Soviet invasion against Gomułka and his supporters transformed the social image of Polish communists. In June, they were still treated as the puppets and servants of alien, anti-Polish interests and excluded from the national community. In October, they became a part of the nation opposing Soviet domination. Gomułka was enthusiastically supported by the great majority of society, not primarily as a communist leader, but as a leader of a nation who, by resisting Soviet demands, embodied a national longing for independence and sovereignty. His name was chanted, along with anti-Soviet slogans, at thousands of meetings: "Go home Rokossovsky

Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Rokossovskiy was a Polish-origin Soviet career officer who was a Marshal of the Soviet Union, as well as Marshal of Poland and Polish Defence Minister, who was famously known for his service in the Eastern Front, where he received high esteem for his outstanding military skill...

", "Down with the Russians," "Long live Gomułka," "We want a free Poland". While his anti-Soviet image was obviously mythical and exaggerated, it was justified in the popular imagination by his anti-Stalinist line in 1948 and years of subsequent internment. Thus, Polish communists found themselves unexpectedly at the head of a national liberation movement. The enthusiastic public support offered to Gomułka contributed to the legitimization of communist rule in Poland, which incorporated mass nationalist, anti-Soviet feelings into the prevailing power structures. In Hungary, social protest destroyed the political system; in Poland, it was absorbed within it.

Aftermath

Information about events in Poland reached the people of HungaryHungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

via Radio Free Europe

Radio Free Europe

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty is a broadcaster funded by the U.S. Congress that provides news, information, and analysis to countries in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East "where the free flow of information is either banned by government authorities or not fully developed"...

's news and commentary services between 19 October and 22 October 1956. A student demonstration in Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

in support of Gomułka, asking for similar reforms in Hungary, was one of the events that sparked the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. The events of the Hungarian November also helped distract the Soviets and ensure the success of the Polish October.

Gomułka, in his public speeches, criticized the hardships of Stalinism and promised reforms to democratize the country; this was received with much enthusiasm by Polish society. By mid-November, Gomułka had secured substantive gains in his negotiations with the Soviets: the cancellation of Poland's existing debts, new preferential trade terms, abandonment of the unpopular Soviet-imposed collectivization of Polish agriculture, and permission to liberalize policy towards the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

. In December, the status of Soviet forces in Poland, the Northern Group of Forces

Northern Group of Forces

The Northern Group of Forces was the military formation of the Soviet Army stationed in Poland from the end of Second World War in 1945 until 1993 when they were withdrawn in the aftermath of the fall of Soviet Union...

, was finally regulated

Status of Forces Agreement

A status of forces agreement is an agreement between a host country and a foreign nation stationing forces in that country. SOFAs are often included, along with other types of military agreements, as part of a comprehensive security arrangement...

.

In the aftermath of the October events, Konstantin Rokossovsky and many other Soviet "advisers" left Poland, signaling that Moscow was willing to grant Polish communists slightly more independence. The Polish government rehabilitated many victims of the Stalinist era, and many political prisoners were set free. Among them was cardinal Stefan Wyszyński. The Polish legislative election of 1957

Polish legislative election, 1957

The Polish legislative election of 1957 was the second election to the Sejm, the parliament of the People's Republic of Poland, and the third in Communist Poland). It took place on 20 January, during the liberalization period following Władysław Gomułka's ascension to power. Although freer than...

was much more liberal than that of 1952 although still not considered free by Western standards.

Gomułka, however, could not and did not want to reject communism or Soviet domination; he could only steer Poland towards increased independence and "Polish national communism". Because of these restricted ambitions, which were recognized by the Soviets, the limited Polish revolution succeeded where the radical Hungarian one did not. Norman Davies

Norman Davies

Professor Ivor Norman Richard Davies FBA, FRHistS is a leading English historian of Welsh descent, noted for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland, and the United Kingdom.- Academic career :...

sums up the effect as a transformation of Poland from puppet state

Puppet state

A puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

to client state

Client state

Client state is one of several terms used to describe the economic, political and/or military subordination of one state to a more powerful state in international affairs...

; Raymond Pearson similarly states that Poland changed from a Soviet colony

Colony

In politics and history, a colony is a territory under the immediate political control of a state. For colonies in antiquity, city-states would often found their own colonies. Some colonies were historically countries, while others were territories without definite statehood from their inception....

to a dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

.

Gomulka's pledge to follow a "Polish road to socialism" more in harmony with national traditions and preferences caused many Poles to interpret the dramatic confrontation of 1956 as a sign that the end of the dictatorship was in sight. Initially very popular for his reforms, which were optimistically referred to at the time as "Gomułka's thaw", Gomułka gradually softened his opposition to Soviet pressures, and the late-1950s hopes for major political change in Poland were replaced with growing disillusionment in the 1960s. In the end, Gomułka failed in his goal to salvage communism—or socialism—in Poland. Society became more liberal

Culture in modern Poland

After the fall of communism Polish culture and society were significantly transformed, as free of heavy government controls they were both liberalized and subject to market forces.-Historical background:...

(as seen, for instance, in the achievements of the Polish Film School

Polish Film School

Polish Film School refers to an informal group of Polish film directors and screenplay writers active between 1955 and approximately 1963.The group was under heavy influence of Italian neorealists. It took advantage of the liberal changes in Poland after the 1956 to portray the complexity of...

and the creation of such controversial movies as Ashes and Diamonds

Ashes and Diamonds (film)

Ashes and Diamonds is a 1958 Polish film directed by Andrzej Wajda, based on the 1948 novel by Polish writer Jerzy Andrzejewski...

), and a civil society

Civil society

Civil society is composed of the totality of many voluntary social relationships, civic and social organizations, and institutions that form the basis of a functioning society, as distinct from the force-backed structures of a state , the commercial institutions of the market, and private criminal...

started to develop, but half-hearted democratization was not enough to satisfy the Polish public. By the time of the March 1968 events, Gomułka's thaw would be long over, and increasing economic problems

Shortage economy

Shortage economy is a term coined by the Hungarian economist, János Kornai. He used this term to criticize the old centrally-planned economies of the communist states of the Eastern Bloc...

and popular discontent would end up removing Gomułka from power in 1970—ironically, in a situation similar to the protests that once had propelled him to power.

Nonetheless, some social scientists, such as Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzezinski is a Polish American political scientist, geostrategist, and statesman who served as United States National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1981....

and Frank Gibney

Frank Gibney

Frank Bray Gibney was an American journalist, editor, writer and scholar. Correspondent of Time, editor of Newsweek and Life, he was the vice chairman of the Board of Editors at Encyclopædia Britannica and wrote several books, most notably about Japan...

, refer to these changes as a revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

—one less dramatic than its Hungarian counterpart but one which may have had an even more profound impact on the Eastern Bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

. Timothy Garton Ash

Timothy Garton Ash

Timothy Garton Ash is a British historian, author and commentator. He is currently serving as Professor of European Studies at Oxford University. Much of his work has been concerned with the late modern and contemporary history of Central and Eastern Europe...

calls the Polish October the most significant event in the post-war history of Poland

History of Poland (1945–1989)

The history of Poland from 1945 to 1989 spans the period of Soviet Communist dominance imposed after the end of World War II over the People's Republic of Poland...

until the rise of Solidarity

History of Solidarity

The history of Solidarity , a Polish non-governmental trade union, begins in August 1980, at the Lenin Shipyards at its founding by Lech Wałęsa and others. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country...

. History professor Ivan Berend notes that while the effects of the Polish October on the Eastern Bloc may be disputed, no doubt exists that it set the course for the eventual fall of communism in the People's Republic of Poland.

Further reading

- Dallin, Alexander. "The Soviet Stake in Eastern Europe". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 317(1958): 138–145.

- “Excerpts from Gomulka's Speech to Central Committee of Polish Communists". New York Times, 21 October 1956: 28.

- Gruson, Sydney. “Soviet Leaders Rush to Poland to Demand Pro-Moscow Regime; Said to Post Troops at Warsaw". New York Times, 20 October 1956: 1.

- Kemp-Welch, Tony. "Dethroning Stalin: Poland 1956 and its Legacy". Europe-Asia StudiesEurope-Asia StudiesEurope-Asia Studies is an academic peer-reviewed journal published 10 times a year by Routledge on behalf of the Institute of Central and East European Studies, University of Glasgow, and continuing the journal Soviet Studies , which was renamed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union...

58(2006): 1261–84. - Kemp-Welch, Tony. "Khrushchev's 'Secret Speech' and Polish Politics: The Spring of 1956". Europe-Asia StudiesEurope-Asia StudiesEurope-Asia Studies is an academic peer-reviewed journal published 10 times a year by Routledge on behalf of the Institute of Central and East European Studies, University of Glasgow, and continuing the journal Soviet Studies , which was renamed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union...

48(1996): 181–206. - Zyzniewski, Stanley J. "The Soviet Economic Impact on Poland". American Slavic and East European Review 18(1959): 205–225.