Polaris expedition

Encyclopedia

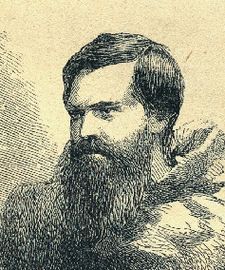

Charles Francis Hall

Charles Francis Hall was an American Arctic explorer. Little is known of Hall's early life. He was born in the state of Vermont, but while he was still a child his family moved to Rochester, New Hampshire, where, as a boy, he was apprenticed to a blacksmith. In the 1840s he married and drifted...

, who intended it to be the first expedition to reach the North Pole

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

. Sponsored by the United States government, it was one of the first serious attempts at the Pole, after that of British naval officer William Edward Parry

William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry was an English rear-admiral and Arctic explorer, who in 1827 attempted one of the earliest expeditions to the North Pole...

, who in 1827 reached latitude 82°45′ North. The expedition failed at its main objective, having been troubled throughout by insubordination, incompetence, and poor leadership.

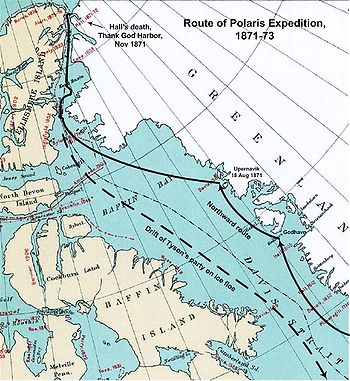

Under Hall's command, the Polaris departed from New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

in June 1871. By October, the men were wintering on the shore of northern Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

, making preparations for the trip to the Pole. Hall returned to the ship from an exploratory sledging journey, and promptly fell ill. Before he died, he accused members of the crew of poisoning him. An exhumation of his body in 1968 revealed that he had ingested a large quantity of arsenic in the last two weeks of his life.

The expedition's notable achievement was reaching 82°29'N latitude by ship, a record at the time. On the way southward, nineteen members of the expedition became separated from the ship and drifted on an ice floe for six months and 1800 miles (2,896.8 km) before being rescued. The damaged Polaris was run aground and wrecked near Etah

Etah, Greenland

Etah is an abandoned settlement in the Qaasuitsup municipality in northern Greenland. It was a starting point of discovery expeditions to the North Pole, and the landing site of the last migration of the Inuit from the Canadian Arctic.- Geography :...

, Greenland, in October 1872. The remaining men were able to survive the winter, and were rescued the following summer. A naval board of inquiry investigated Hall's death, but no charges were ever laid.

Origins

William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry was an English rear-admiral and Arctic explorer, who in 1827 attempted one of the earliest expeditions to the North Pole...

led a British Royal Navy expedition with the aim to be the first men to reach the North Pole. In the 50 years following Parry's attempt, the Americans would mount three such expeditions: Elisha Kent Kane in 1853–55, Isaac Israel Hayes

Isaac Israel Hayes

Isaac Israel Hayes was an Arctic explorer and physician.Hayes was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania. After completing his medical studies at the University of Pennsylvania, Hayes signed on as ship's surgeon for an 1853-5 expedition led by Elisha Kent Kane to search for John Franklin...

in 1860–61, and Charles Francis Hall

Charles Francis Hall

Charles Francis Hall was an American Arctic explorer. Little is known of Hall's early life. He was born in the state of Vermont, but while he was still a child his family moved to Rochester, New Hampshire, where, as a boy, he was apprenticed to a blacksmith. In the 1840s he married and drifted...

with the Polaris in 1871–73.

Hall had no special academic background or sailing experience (he was a blacksmith, engraver, then owner of a Cincinnati newspaper), but he was a voracious reader with an obsession for the Arctic. After John Franklin's

John Franklin

Rear-Admiral Sir John Franklin KCH FRGS RN was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. Franklin also served as governor of Tasmania for several years. In his last expedition, he disappeared while attempting to chart and navigate a section of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic...

1845 expedition

Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a doomed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845. A Royal Navy officer and experienced explorer, Franklin had served on three previous Arctic expeditions, the latter two as commanding officer...

was lost, Hall's focus was directed toward the Arctic. He was able to launch two expeditions in search of Franklin and his crew; one in 1860–63, and a second in 1864–69. These experiences established him as a seasoned Arctic explorer, and gave him valuable contacts among the Inuit

Inuit

The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Canada , Denmark , Russia and the United States . Inuit means “the people” in the Inuktitut language...

people. The notoriety he gained eventually allowed him to convince the United States government to fund his third expedition, an attempt on the North Pole.

Finance and materiel

In 1870, a bill was introduced in the SenateUnited States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

called the Arctic Resolution, to fund an expedition to the North Pole. Hall lobbied for, and received, a grant of $50,000 from the U.S. Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

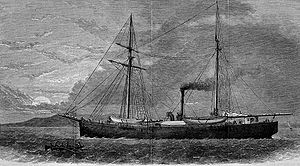

to command the expedition and began recruiting personnel in late 1870. He secured the U.S. Navy tugboat Periwinkle, a 387-ton screw-propelled steamer. At the Washington Navy Yard

Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy...

the ship was fitted as a fore topsail schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

, and renamed Polaris. She was prepared for Arctic service by the addition of solid oak timber all over her hull, and the bow was sheathed in iron. A new engine was added, and one of the boilers was retrofitted to burn seal or whale oil.

The ship was also outfitted with four whaleboat

Whaleboat

A whaleboat is a type of open boat that is relatively narrow and pointed at both ends, enabling it to move either forwards or backwards equally well. It was originally developed for whaling, and later became popular for work along beaches, since it does not need to be turned around for beaching or...

s, 20 feet (6.1 m) long and 4 feet (1.2 m) wide, and a flat-bottomed scow

Scow

A scow, in the original sense, is a flat-bottomed boat with a blunt bow, often used to haul bulk freight; cf. barge. The etymology of the word is from the Dutch schouwe, meaning such a boat.-Sailing scows:...

. During his previous Arctic expeditions, Hall came to admire the Inuit umiak

Umiak

The umiak, umialak, umiaq, umiac, oomiac or oomiak is a type of boat used by Eskimo people, both Yupik and Inuit, and was originally found in all coastal areas from Siberia to Greenland. First arising in Thule times, it has traditionally been used in summer to move people and possessions to...

, and brought a similarly constructed collapsible boat which could hold 20 men. Food packed on board consisted of tinned ham, salted beef, bread and sailor's biscuit. The men intended to supplement their diet with fresh muskox, seal and polar bear, in order to ward off scurvy

Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

.

Personnel

In the spring of 1871, U.S. President Ulysses S. GrantUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

had named Hall as overall commander of the expedition, and he was being referred to as Captain. Though Hall had abundant Arctic experience, he had no sailing experience, and so the title was purely honorary. In selecting the officers and seamen, Hall relied heavily on whalers with experience in the Arctic. This was markedly different from the polar expeditions of the British Admiralty, which tended to use naval officers and highly disciplined crews.

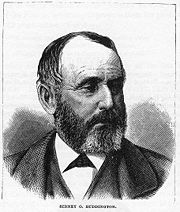

For his selection of sailing master

Captain (nautical)

A sea captain is a licensed mariner in ultimate command of the vessel. The captain is responsible for its safe and efficient operation, including cargo operations, navigation, crew management and ensuring that the vessel complies with local and international laws, as well as company and flag...

, Hall first turned to Sidney O. Budington, then to George Tyson, who both initially declined due to prior whaling commitments. When those commitments fell through, Hall named Budington as sailing master and Tyson assistant navigator. Budington and Tyson had decades of experience between them captaining whaling vessels

Whaler

A whaler is a specialized ship, designed for whaling, the catching and/or processing of whales. The former included the whale catcher, a steam or diesel-driven vessel with a harpoon gun mounted at its bows. The latter included such vessels as the sail or steam-driven whaleship of the 16th to early...

. In effect, the Polaris now had three captains, a fact which would weigh heavily on the fate of the expedition. Further complicating matters, in 1863 Budington and Hall had quarrelled because Budington had denied permission for Hall to bring his Inuit guides, Joseph Ebierbing

Ebierbing

Ebierbing , also known as "Joe," "Eskimo Joe," and "Joseph Ebierbing", c. 1837 - c. 1881, was a remarkable Inuit guide and explorer, who assisted several American Arctic explorers, among them Charles Francis Hall and Frederick Schwatka...

and Tookoolito

Tookoolito

Tookoolito known as "Hannah" among whalers of Cumberland Sound, was an Inuk woman who served as translator and guide to Charles Francis Hall, an Arctic explorer involved in the search for Franklin's lost expedition in the 1860s and 1870's...

, with him on an expedition at a time when they were ill and in Budington's care.

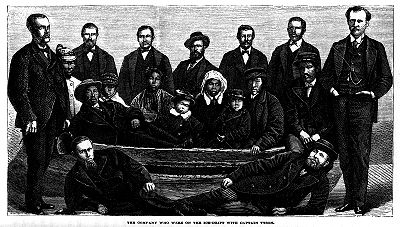

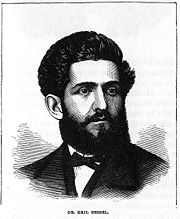

The rest of the officers and scientific staff were Americans (first mate Hubbard Chester, second mate William Morton, and astronomer and chaplain R.W.D. Bryan) and Germans (chief scientist and surgeon Emil Bessels

Emil Bessels

Dr. Emil Bessels was a German Jewish physician and Arctic explorer. Born in Heidelberg, Germany, he studied medicine and natural sciences in his home town and at the university of Jena. Bessels spent much of his scientific career working for the Smithsonian Institution...

and meteorologist Frederick Meyer). The seamen were mostly German, as was chief engineer Emil Schumann. In addition to the 25 officers, crew, and scientific staff, Hall brought Inuit interpreter and hunter Ebierbing, his wife Tookoolito, and their child. A Greenlandic

Greenlandic

Greenlandic may refer to:* Something of, from, or related to Greenland, the self-governing Danish province located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago....

aboriginal named Hans Hendrik

Hans Hendrik

Hans Hendrik, also known as Hans Christian, native name Suersaq , was a Greenlandic Arctic traveller and interpreter, born in the southern settlement of Fiskernaes .-Supporting the Kane Expedition:...

, his wife Merkut and three children also joined the expedition.

New York to Upernavik

Brooklyn Navy Yard

The United States Navy Yard, New York–better known as the Brooklyn Navy Yard or the New York Naval Shipyard –was an American shipyard located in Brooklyn, northeast of the Battery on the East River in Wallabout Basin, a semicircular bend of the river across from Corlear's Hook in Manhattan...

on June 29, 1871, the expedition ran into personnel troubles. The cook, a seaman, a fireman, and assistant engineer Wilson deserted

Desertion

In military terminology, desertion is the abandonment of a "duty" or post without permission and is done with the intention of not returning...

. The steward turned out to be a drunk, and was left in port.

The ship stopped in New London, Connecticut

New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States.It is located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, southeastern Connecticut....

, to pick up a replacement assistant engineer, leaving on July 3, 1871. By the time the ship reached St. John's

St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador

St. John's is the capital and largest city in Newfoundland and Labrador, and is the oldest English-founded city in North America. It is located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland. With a population of 192,326 as of July 1, 2010, the St...

, there was dissension among the officers and scientific staff. Bessels, backed up by Meyer, had openly rejected Hall's command over the scientific staff. The dissension spread to the crew, which was divided along nationalist lines. In his diary, Assistant Navigator George Tyson wrote that by the time they reached Disko Island

Disko Island

Disko Island is a large island in Baffin Bay, off the west coast of Greenland. It has an area of , making it the second largest island of Greenland and one of the 100 largest islands in the world...

, Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

, "...expressions are freely made that Hall shall not get any credit from this expedition. Already some have made up their minds how far they will go and when they will get home again." Hall asked Captain Davenport of the supply ship Congress to intervene. Davenport threatened to have Meyer shackled for insubordination and sent back to the United States, at which point all of the Germans threatened to quit. Hall and Davenport were forced to back down, however Davenport delivered a strongly worded speech on naval discipline to the crew.

In another open display of dissent, the ship's boilers had been tampered with by one of the crew. The special blubber-fired boilers had disappeared, apparently thrown overboard.

On Aug 18, 1871, the ship reached Upernavik

Upernavik

Upernavik is a small town in the Qaasuitsup municipality in northwestern Greenland, located on a small island of the same name. With 1,129 inhabitants as of 2010, it is the thirteenth-largest town in Greenland. Due to the small size of the settlement, everything is within walking distance...

on Greenland's west coast, where they picked up the Inuit hunter and interpreter Hans Hendrik

Hans Hendrik

Hans Hendrik, also known as Hans Christian, native name Suersaq , was a Greenlandic Arctic traveller and interpreter, born in the southern settlement of Fiskernaes .-Supporting the Kane Expedition:...

. The Polaris proceeded north through Smith Sound

Smith Sound

Smith Sound is an uninhabited Arctic sea passage between Greenland and Canada's northernmost island, Ellesmere Island. It links Baffin Bay with Kane Basin and forms part of the Nares Strait....

and Nares Strait

Nares Strait

Nares Strait is a waterway between Ellesmere Island and Greenland that is the northern part of Baffin Bay where it meets the Lincoln Sea. From south to north, the strait includes Smith Sound, Kane Basin, Kennedy Channel, Hall Basin and Robeson Channel...

, passing previous furthest north records (by ship) held by Elisha Kane

Elisha Kane

Elisha Kent Kane was a medical officer in the United States Navy during the first half of the 19th century. He was a member of two Arctic expeditions to rescue the explorer Sir John Franklin...

and Isaac Hayes

Isaac Israel Hayes

Isaac Israel Hayes was an Arctic explorer and physician.Hayes was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania. After completing his medical studies at the University of Pennsylvania, Hayes signed on as ship's surgeon for an 1853-5 expedition led by Elisha Kent Kane to search for John Franklin...

.

Polar preparations and Hall's death

By Sept. 2, 1871, Polaris had reached her furthest north of 82°29'N. Tension flared again as the three leading officers could not agree on whether to proceed further or not. Hall and Tyson wanted to press north, to cut down the distance they would have to travel to the Pole by dogsled. Budington did not want to further risk the ship, and walked out on the discussion. In the end, they sailed into Thank God Harbor (now called Hall Bay) on Sept. 10, 1871, and settled in for the winter on the shore of northern GreenlandGreenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

.

Within a few weeks, Hall was making preparations for a sledging trip with the aim of beating Sir William Parry's furthest north record. Mistrust amongst the men in charge showed again when Hall told Tyson that "I cannot trust that man (Captain Budington). I want you to go with me, but don't know how to leave him alone with the ship." There is some evidence that Budington may have been an alcoholic; on at least three occasions he raided the ship's stores, including the alcohol kept by the scientists for preservation of specimens. Hall had complained about Budington's drunken behavior, and it fully came to light from the crew's testimony at the inquest following the expedition. With Tyson watching over the ship, Hall took two sledges with first mate Chester, and the native guides Ebierbing and Hendrik, leaving on Oct 10, 1871. The day after leaving, Hall sent Hendrik back to the ship to retrieve a number of forgotten items. Hall also sent back a note to Bessels, reminding him to wind the chronometer

Chronometer

Chronometer may refer to:* Chronometer watch, a watch tested and certified to meet certain precision standards* Hydrochronometer, a water clock* Marine chronometer, a timekeeper used for celestial navigation...

s at the right time every day. In his book Trial by Ice, Richard Parry postulated that such a note from the uneducated Hall must have rankled Bessels, who held a number of degrees from Stuttgart

University of Stuttgart

The University of Stuttgart is a university located in Stuttgart, Germany. It was founded in 1829 and is organized in 10 faculties....

, Heidelberg, and Jena. It was another example of Hall's micromanagement

Micromanagement

In business management, micromanagement is a management style where a manager closely observes or controls the work of her or his subordinates or employees...

of the expedition. Before he left on the overland trip, Hall gave Budington a detailed list of instructions regarding how to manage the ship in his absence. This likely did not sit well with a sailing master with over 20 years of experience.

Upon their return on Oct 24, 1871, Hall suddenly fell ill after drinking a cup of coffee. His symptoms started with an upset stomach, then progressed to vomiting and delirium the following day. Hall accused several of the ship's company, including Bessels, of having poisoned him. Following these accusations, he refused medical treatment from Bessels, and drank only liquids delivered directly by his Inuit friend Tookoolito. He seemed to improve for a few days, and was even able to go up on deck. Bessels had prevailed upon Bryan, the ship's chaplain, to convince Hall to allow the doctor to see him. By November 4, Hall relented, and Bessels resumed treatment. Shortly after, Hall's condition began to deteriorate, and he suffered vomiting and delirium, and collapsed. Bessels diagnosed apoplexy

Apoplexy

Apoplexy is a medical term, which can be used to describe 'bleeding' in a stroke . Without further specification, it is rather outdated in use. Today it is used only for specific conditions, such as pituitary apoplexy and ovarian apoplexy. In common speech, it is used non-medically to mean a state...

, and Hall finally died on November 8. He was taken ashore and given a formal burial.

Attempt at North Pole

According to the protocol provided by Navy Secretary George M. RobesonGeorge M. Robeson

George Maxwell Robeson was an American Republican Party politician and lawyer from New Jersey who served as a Union army general during the American Civil War, and then as Secretary of the Navy during the Grant administration. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1879 to...

, command of the expedition was turned over to Budington, under whom discipline further devolved. The precious coal was being burned at a high rate: 6334 pounds (2,873.1 kg) in November, which was 1596 pounds (723.9 kg) more than the previous month, and close to 8300 pounds (3,764.8 kg) in December. Budington was often seen to be drunk, but he was far from the only one to pilfer the alcohol stores; according to testimony at the Inquiry, Tyson was also seen "drunk like old mischief", and Schumann had gone so far as to make a duplicate of Budington's key so that he could help himself to alcohol as well. Whatever the role of alcohol, it was clear that shipboard routine was breaking down; as Tyson remarked, "There is so little regularity observed. There is no stated time for putting out lights; the men are allowed to do as they please; and, consequently, they often make nights hideous by their carousing, playing cards to all hours." For purposes unknown, Budington chose to issue the ship's supply of firearms to the crew.

Farley Mowat

Farley McGill Mowat, , born May 12, 1921 is a conservationist and one of Canada's most widely-read authors.His works have been translated into 52 languages and he has sold more than 14 million books. He achieved fame with the publication of his books on the Canadian North, such as People of the...

has suggested the officers were contemplating faking a journey to the Pole, or at least to a very high latitude.

Whatever the unmentioned plan was, an expedition to try for the Pole was dispatched on June 6, 1872. Chester led the expedition in a whaleboat, but this was crushed by the ice within a few miles of Polaris. Chester and his men hiked back to the ship, and persuaded Budington to give them the collapsible boat. With this, and Tyson piloting another whaleboat, the men set northward again. In the meantime, the Polaris had found open water, and was searching for a route south. Budington, not eager to spend another winter in the ice, sent Ebierbing north with orders for the Tyson and Chester: return to the ship at once. The men were forced to abandon both craft and walk 20 miles (32.2 km) back to Polaris. Now three of the ship's precious lifeboats were lost, and a fourth (the small scow) would be crushed by ice in July after being carelessly left out overnight. The expedition had failed in its main objective to reach the North Pole.

Fate of Polaris and journeys home

With the expedition's main goal abandoned, Polaris turned south for home. In Smith SoundSmith Sound

Smith Sound is an uninhabited Arctic sea passage between Greenland and Canada's northernmost island, Ellesmere Island. It links Baffin Bay with Kane Basin and forms part of the Nares Strait....

, west of the Humboldt Glacier

Humboldt Glacier

Humboldt Glacier is the widest tidewater glacier in the Northern Hemisphere. It borders the Kane Basin in North West Greenland. Its front is wide. It has been retreating in the period of observation spanning 1975-2010. The glacier is named after German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt.-Footnotes:...

, she ran aground on a shallow iceberg and could not be freed. On the night of October 15, 1872, with an iceberg threatening the ship, Schuman reported that water was coming in and the pumps could not keep up. Budington ordered cargo to be thrown onto the ice to buoy the ship. Men began throwing goods overboard, as Tyson put it, "with no care taken as to how or where these things were thrown". Much of the jettisoned cargo was lost.

A number of the crew were out on the surrounding ice during the night when a break-up of the pack occurred. When morning came, the group, consisting of Tyson, Meyer, six of the seamen, the cook, the steward, and all of the Inuit, found themselves stranded on an ice floe. The castaways could see the Polaris 8 to 10 mi (12.9 to 16.1 km) away, but attempts to attract the

Davis Strait

Davis Strait is a northern arm of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Nunavut, Canada's Baffin Island. The strait was named for the English explorer John Davis , who explored the area while seeking a Northwest Passage....

and would soon be within rowing distance of Disko. He was incorrect; the men were actually on the Canadian side of the strait. The error caused the men to reject Tyson's plans for conserving. The seamen soon broke up one of the whaleboats for firewood, making a safe escape to land very unlikely. One night in November, the men went on an eating binge, consuming a large quantity of the food stores. The group drifted on the ice floe for the next six months over 1800 miles (2,896.8 km) before being rescued off the coast of Newfoundland by the sealer Tigress

USS Tigress (1871)

The third USS Tigress was a screw steamer of the United States Navy, chartered during 1873 to mount an Arctic rescue mission.-Whaler, 1871–1873:...

on April 30, 1873. All probably would have perished had the group not included the skilled Inuit hunters Ebierbing and Hendrik, who were able to kill seal on a number of occasions. Despite this, scarcely a word was written about the Inuit in either the official reports of the expedition, or the press.

On October 16, with the ship's coal stores running low, Captain Budington decided to run the Polaris aground near Etah

Etah, Greenland

Etah is an abandoned settlement in the Qaasuitsup municipality in northern Greenland. It was a starting point of discovery expeditions to the North Pole, and the landing site of the last migration of the Inuit from the Canadian Arctic.- Geography :...

. Having lost much of their bedding, clothing, and food when it was haphazardly jettisoned from the ship on October 12, the remaining 14 men were in poor condition to face another winter. They built a hut from lumber salvaged from the ship, and on October 24, extinguished the ship's boilers to conserve coal. The bilge pumps stopped for good, and the ship heeled over on her side, half out of water. Fortunately, the Etah Inuit helped the men survive the winter. After wintering ashore, the crew built two boats from salvaged wood from the ship, and on June 3 the crew sailed south. They were spotted and rescued in July by the whaler Ravenscraig, and returned home via Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

.

Inquiry

On June 5, 1873, a United States Navy board of inquiry began. At this time, the crew and Inuit families had been rescued from the ice floe, however the fate of Budington, Bessels, and the remainder of the crew was still unknown. The board consisted of Admiral Louis M. GoldsboroughLouis M. Goldsborough

Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough was a rear admiral in the United States Navy during the Civil War. He held several sea commands during the Civil War, including the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron...

, Secretary of the Navy Robeson, Commodore Reynolds, Captain Henry W. Howgate

Henry W. Howgate

Capt. Henry W. Howgate was Chief Disbursing Officer in the United States Army Signal Corps and responsible for major Arctic explorations...

of the Army, and Spencer F. Baird

Spencer Fullerton Baird

Spencer Fullerton Baird was an American ornithologist, ichthyologist and herpetologist. Starting in 1850 he was assistant-secretary and later secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C...

of the Academy of Sciences

United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences is a corporation in the United States whose members serve pro bono as "advisers to the nation on science, engineering, and medicine." As a national academy, new members of the organization are elected annually by current members, based on their distinguished and...

. Tyson was the first to appear for questioning, and related the friction between Hall, Budington, and Bessels, and Hall's deathbed accusations of poisoning. The board also inquired about the whereabouts of Hall's journals and records. Tyson responded that while Hall was delirious, he instructed Budington to burn some of the papers, and the rest had disappeared. Later, journals of other crew members were discovered at the site of the Polaris wreck, but these had the sections regarding Hall's death cut out. Meyer testified to Budington's drinking, saying that the sailing master was "drunk most always while we were going southward". Steward John Herron testified that he had not made the coffee that Hall had suspected of being laced with poison; he explained that the cook made the coffee, and that he had not kept track of how many people had touched the cup before it was brought to Hall.

Quinine

Quinine is a natural white crystalline alkaloid having antipyretic , antimalarial, analgesic , anti-inflammatory properties and a bitter taste. It is a stereoisomer of quinidine which, unlike quinine, is an anti-arrhythmic...

to correct his elevated temperature before he died.

Faced with conflicting testimony, lack of official records and journals, and no body for an autopsy, no charges were laid in connection with Hall's death. In the inquiry's final report, the surgeons general of the Army and Navy wrote: "From the circumstances and symptoms detailed by him, and comparing them with the medical testimony of all the witnesses, we are conclusively of the opinion that Captain Hall died from natural causes, viz., apoplexy; and that the treatment of the case by Dr. Bessel [sic] was the best practicable under the circumstances."

Controversy

Budington's decision to beach the Polaris is equally controversial. Budington said that he "believed the propeller was smashed and the rudder broken". The official report of the expedition states that the vessel should have been abandoned because "there was only coal enough to keep the fires alive for five days". However, the same report states that the propeller and rudder were in fact discovered to be intact after the ship was run aground, and the ship's boiler and sails were available. Even if she ran out of coal, the ship was perfectly able to travel under sail alone. In defense of Budington's decision, when low tide exposed the ship's hull, the men found that the stem

Stem (ship)

The stem is the very most forward part of a boat or ship's bow and is an extension of the keel itself and curves up to the wale of the boat. The stem is more often found on wooden boats or ships, but not exclusively...

had completely broken away at the six-foot mark, taking iron sheeting and planking with it. Budington wrote in his journal that he "called the officer's attention to it, who only wondered she had kept afloat so long".

Regarding Hall's fate, the official investigation that followed ruled the cause of death was apoplexy

Apoplexy

Apoplexy is a medical term, which can be used to describe 'bleeding' in a stroke . Without further specification, it is rather outdated in use. Today it is used only for specific conditions, such as pituitary apoplexy and ovarian apoplexy. In common speech, it is used non-medically to mean a state...

(an early term for stroke

Stroke

A stroke, previously known medically as a cerebrovascular accident , is the rapidly developing loss of brain function due to disturbance in the blood supply to the brain. This can be due to ischemia caused by blockage , or a hemorrhage...

). Some of Hall's symptoms — partial paralysis, slurred speech, delirium — certainly fit that diagnosis. Indeed, the pains that Hall complained about down one side of his body, which he attributed to many years' huddling in an igloo, may have been due to a previous minor stroke. However, in 1968, Hall's biographer Chauncey C. Loomis, a professor at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College is a private, Ivy League university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. The institution comprises a liberal arts college, Dartmouth Medical School, Thayer School of Engineering, and the Tuck School of Business, as well as 19 graduate programs in the arts and sciences...

, made an expedition to Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

to exhume Hall's body. Because of the permafrost

Permafrost

In geology, permafrost, cryotic soil or permafrost soil is soil at or below the freezing point of water for two or more years. Ice is not always present, as may be in the case of nonporous bedrock, but it frequently occurs and it may be in amounts exceeding the potential hydraulic saturation of...

, Hall's body, flag shroud, clothing and coffin were remarkably well-preserved. Tests on tissue samples of bone, fingernails and hair showed that Hall had received large doses of arsenic

Arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As, atomic number 33 and relative atomic mass 74.92. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in conjunction with sulfur and metals, and also as a pure elemental crystal. It was first documented by Albertus Magnus in 1250.Arsenic is a metalloid...

in the last two weeks of his life. Arsenic poisoning appears consistent with the symptoms party members reported: stomach pains, vomiting, stupor, and mania

Mania

Mania, the presence of which is a criterion for certain psychiatric diagnoses, is a state of abnormally elevated or irritable mood, arousal, and/ or energy levels. In a sense, it is the opposite of depression...

. Arsenic can have a sweet taste, and Hall had complained that the coffee had tasted too sweet, and had burned his stomach. It also appears that at least three of the crew, Budington, Meyer, and Bessels, expressed relief at Hall's death and said that the expedition would be better off without him. In his book The Arctic Grail, Pierre Berton

Pierre Berton

Pierre Francis de Marigny Berton, was a noted Canadian author of non-fiction, especially Canadiana and Canadian history, and was a well-known television personality and journalist....

suggests that it is possible that Hall accidentally dosed himself with the poison, as arsenic was common in medical kits of the time. But it is considered more probable that he was murdered by one of the other members of the expedition, possibly Bessels, who was in nearly constant attendance of Hall. No charges were ever filed.

Further reading

- Henderson, Bruce. Fatal North: Adventure and Survival Aboard USS Polaris, The First U.S. Expedition to the North Pole. NAL Hardcover (2001). ISBN 0-451-40935-3

- Heighton, Steven. "Afterlands". Houghton Mifflin (February 6, 2006). ISBN 0618139346

Research Resources

- Scrapbooks on the Polaris Expedition held at the American Geographical Society Library, UW Milwaukee