Plantations of Ireland

Encyclopedia

Colonisation

Colonization occurs whenever any one or more species populate an area. The term, which is derived from the Latin colere, "to inhabit, cultivate, frequent, practice, tend, guard, respect", originally related to humans. However, 19th century biogeographers dominated the term to describe the...

of this land with settlers from England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and the Scottish Lowlands

Scottish Lowlands

The Scottish Lowlands is a name given to the Southern half of Scotland.The area is called a' Ghalldachd in Scottish Gaelic, and the Lawlands ....

.

They followed smaller-scale emigration to Ireland as far back as the 12th century, which had resulted in a distinct ethnicity in Ireland known as the Old English

Old English (Ireland)

The Old English were the descendants of the settlers who came to Ireland from Wales, Normandy, and England after the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–71. Many of the Old English became assimilated into Irish society over the centuries...

.

The 16th century plantations were established throughout the country by the confiscation of lands occupied by Gael

Gaël

Gaël is a commune in the Ille-et-Vilaine department of Brittany in north-western France.It lies southwest of Rennes between Saint-Méen-le-Grand and Mauron...

ic clans and Hiberno-Norman

Hiberno-Norman

The Hiberno-Normans are those Norman lords who settled in Ireland who admitted little if any real fealty to the Anglo-Norman settlers in England, and who soon began to interact and intermarry with the Gaelic nobility of Ireland. The term embraces both their origins as a distinct community with...

dynasties, but principally in the provinces

Provinces of Ireland

Ireland has historically been divided into four provinces: Leinster, Ulster, Munster and Connacht. The Irish word for this territorial division, cúige, literally meaning "fifth part", indicates that there were once five; the fifth province, Meath, was incorporated into Leinster, with parts going to...

of Munster

Munster

Munster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the south of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes...

and Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

. The lands were then granted by Crown authority to colonists ("planters") from England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

. This process began during the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

and continued under Mary I

Mary I of England

Mary I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death.She was the only surviving child born of the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry in 1547...

and Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

. It was accelerated under James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

and Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

, and in their time the planters came also from Scotland

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

.

The early plantations

Plantation (settlement or colony)

Plantation was an early method of colonization in which settlers were "planted" abroad in order to establish a permanent or semi-permanent colonial base. Such plantations were also frequently intended to promote Western culture and Christianity among nearby indigenous peoples, as can be seen in the...

in the 16th century tended to be based on small "exemplary" colonies. The later plantations were based on mass confiscations of land from Irish landowners and the subsequent importation of large numbers of settlers from England and Wales

England and Wales

England and Wales is a jurisdiction within the United Kingdom. It consists of England and Wales, two of the four countries of the United Kingdom...

, later also from Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

.

The final official plantations took place under the English Commonwealth and Cromwell’s Protectorate

The Protectorate

In British history, the Protectorate was the period 1653–1659 during which the Commonwealth of England was governed by a Lord Protector.-Background:...

during the 1650s, when thousands of Parliamentarian

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

soldiers were settled in Ireland. Outside of the plantations, significant migration into Ireland continued well into the 18th century, from both Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

and continental Europe

Continental Europe

Continental Europe, also referred to as mainland Europe or simply the Continent, is the continent of Europe, explicitly excluding European islands....

.

The plantations changed the demography of Ireland by creating large communities with a British and Protestant identity. These communities replaced the older Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

ruling class, which shared with the general population a common Irish identity and set of political attitudes. The physical and economic nature of Irish society was also changed, as new concepts of ownership, trade and credit were introduced. These changes led to the creation of a Protestant ruling class

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

, which secured the authority of Crown government in Ireland during the 17th century.

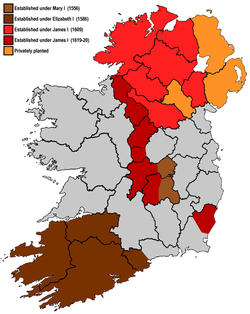

Early Plantations (1556–1576)

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

. Ireland was to become a peaceful and reliable possession, without risk of rebellion or foreign invasion. Wherever the policy of surrender and regrant

Surrender and regrant

During the Tudor conquest of Ireland , "surrender and regrant" was the legal mechanism by which Irish clans were to be converted from a power structure rooted in clan and kin loyalties, to a late-feudal system under the English legal system...

failed, plantations were effected.

To this end, two forms of plantation were adopted in the first half of the 16th century. The first was the "exemplary plantation", in which small colonies of English would provide model farming communities that the Irish could emulate. One such colony was planted in the late 1560s, at Kerrycurrihy near Cork city

Cork (city)

Cork is the second largest city in the Republic of Ireland and the island of Ireland's third most populous city. It is the principal city and administrative centre of County Cork and the largest city in the province of Munster. Cork has a population of 119,418, while the addition of the suburban...

, on land leased from the Earl of Desmond

Earl of Desmond

The title of Earl of Desmond has been held historically by lords in Ireland, first as a title outside of the peerage system and later as part of the Peerage of Ireland....

.

The second form set the trend for future English policy in Ireland. It was punitive in nature, as it provided for the plantation of English settlers on lands confiscated following the suppression of rebellions. The first such scheme was the Plantation of King's County (now Offaly) and Queen's County (now Laois) in 1556, naming them after the new Catholic monarchs Philip

Philip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

and Mary respectively. The new county town

County town

A county town is a county's administrative centre in the United Kingdom or Ireland. County towns are usually the location of administrative or judicial functions, or established over time as the de facto main town of a county. The concept of a county town eventually became detached from its...

s were named Philipstown (now Daingean

Daingean

Daingean , formerly Philipstown, is a small town in east County Offaly, Ireland. It is situated midway between the towns of Tullamore and Edenderry on the R402 regional road. The town or townland of Daingean has a population of 777 while the District Electoral Division has a total population of...

) and Maryborough (now Portlaoise). An Act was passed "whereby the King and Queen's Majesties, and the Heires and Successors of the Queen, be entituled to the Counties of Leix, Slewmarge, Irry, Glinmaliry, and Offaily, and for making the same Countries Shire Grounds."

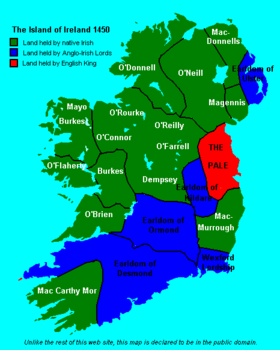

The O’Moore and O’Connor clans, which occupied the area, had traditionally raided the English-ruled Pale

The Pale

The Pale or the English Pale , was the part of Ireland that was directly under the control of the English government in the late Middle Ages. It had reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast stretching from Dalkey, south of Dublin, to the garrison town of Dundalk...

around Dublin. The Lord Deputy of Ireland

Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the King's representative and head of the Irish executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and later the Kingdom of Ireland...

, the Earl of Sussex

Earl of Sussex

Earl of Sussex is a title that has been created several times in the Peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. The early Earls of Arundel were often also called Earls of Sussex....

, ordered that they be dispossessed and replaced with an English settlement. However, the plantation was not a great success. The O’Moores and O’Connors retreated to the hills and bogs and fought a local war against the settlement for much of the following 40 years. In 1578, the English finally subdued the displaced O’Moore clan by massacring

Massacre of Mullaghmast

The Massacre of Mullaghmast refers to the summary execution of Irish chieftains by the British military in Ireland. It probably occurred in the year 1578...

most of their fine (or ruling families) at Mullaghmast

Mullaghmast

Mullaghmast , is a hill in the south of County Kildare, Leinster, near the village of Ballitore. It was an important site in prehistory, in early history and again in more recent times...

in Laois, having invited them there for peace talks. Rory Óg Ó Moore, the leader of rebellion in the area, was also hunted down and killed later that year. The ongoing violence meant that the authorities had difficulty in attracting people to settle in their new plantation and settlement ended up clustered around a series of military fortifications.

Another failed plantation occurred in eastern Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

in the 1570s. The east of the province (occupied by the MacDonnells and Clandeboye O’Neills) was intended to be colonised with English planters, to put a barrier between the Gaels

Gaels

The Gaels or Goidels are speakers of one of the Goidelic Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Goidelic speech originated in Ireland and subsequently spread to western and northern Scotland and the Isle of Man....

of Ireland and Scotland and to stop the flow of Scottish mercenaries into Ireland. The conquest of east Ulster was contracted out to the Earl of Essex

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, KG , an English nobleman and general. From 1573 until his death he fought in Ireland in connection with the Plantation of Ulster, where he ordered the massacre of Rathlin Island...

and Sir Thomas Smith. The O’Neill chieftain, Turlough Luineach O'Neill

Turlough Luineach O'Neill

Toirdhealbhach Luineach Mac Néill Chonnalaigh Ó Néill , the earl of the Clan-Connell, was inaugurated as the King of Tyrone, upon Shane O’Neill’s death...

, fearing an English bridgehead in Ulster, helped his O’Neill kinsmen of Clandeboye. The MacDonnells in Antrim

County Antrim

County Antrim is one of six counties that form Northern Ireland, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of 2,844 km², with a population of approximately 616,000...

, led by Sorley Boy MacDonnell

Sorley Boy MacDonnell

Somhairle Buidhe Mac Domhnaill , Scoto-Irish prince or flaith and chief, was the son of Alexander MacDonnell, lord of Islay and Kintyre , and Catherine, daughter of the Lord of Ardnamurchan...

were also able to call on reinforcements from their kinsmen in the Western Isles and Highlands

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

of Scotland.

The plantation eventually degenerated into a series of atrocities against the local civilian population before finally being abandoned. Brian MacPhelim O’Neill of Clandeboye, his wife and 200 clansmen were murdered at a feast organised by Essex in 1574. In 1575, Francis Drake

Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake, Vice Admiral was an English sea captain, privateer, navigator, slaver, and politician of the Elizabethan era. Elizabeth I of England awarded Drake a knighthood in 1581. He was second-in-command of the English fleet against the Spanish Armada in 1588. He also carried out the...

(later victor over the Spanish Armada

Spanish Armada

This article refers to the Battle of Gravelines, for the modern navy of Spain, see Spanish NavyThe Spanish Armada was the Spanish fleet that sailed against England under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidonia in 1588, with the intention of overthrowing Elizabeth I of England to stop English...

, then in the pay of the Earl of Essex) participated in a naval expedition that culminated in the massacre of 500 MacDonnell clans-people in a surprise raid on Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island is an island off the coast of County Antrim, and is the northernmost point of Northern Ireland. Rathlin is the only inhabited offshore island in Northern Ireland, with a rising population of now just over 100 people, and is the most northerly inhabited island off the Irish coast...

, though according to Harry Kelsey: 'Drake's own role in the massacre is unclear'.

The following year, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

, disturbed by the killing of civilians, called a halt.

Munster Plantation (1586 onwards)

The Munster Plantation of the 1580s was the first mass plantation in Ireland . It was instituted as punishment for the Desmond RebellionsDesmond Rebellions

The Desmond Rebellions occurred in 1569-1573 and 1579-1583 in the Irish province of Munster.They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond – head of the FitzGerald dynasty in Munster – and his followers, the Geraldines and their allies against the threat of the extension of Elizabethan English...

, when the Geraldine Earl of Desmond

Earl of Desmond

The title of Earl of Desmond has been held historically by lords in Ireland, first as a title outside of the peerage system and later as part of the Peerage of Ireland....

had rebelled against English interference in Munster

Munster

Munster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the south of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes...

. The Desmond dynasty was annihilated in the aftermath of the Second Desmond Rebellion

Second Desmond Rebellion

The Second Desmond rebellion was the more widespread and bloody of the two Desmond Rebellions launched by the FitzGerald dynasty of Desmond in Munster, Ireland, against English rule in Ireland...

(1579–83) and their estates were confiscated. This gave the English authorities the opportunity to settle the province with colonists from England and Wales, who, it was hoped, would be a bulwark against further rebellions. In 1584, the Surveyor General

Surveyor General

The Surveyor General is an official responsible for government surveying in a specific country or territory. Originally this would often have been a military appointment, but is now more likely to be a civilian post....

of Ireland, Sir Valentine Browne

Sir Valentine Browne, Knight

Sir Valentine Browne, of Crofts, Lincolnshire, was an English politician.-Life:Valentine Browne was the son of Sir Valentine Browne of Croft, Lincolnshire and may have been educated at Trinity College, Cambridge...

and a commission surveyed Munster, to allocate confiscated lands to English Undertakers (wealthy colonists who "undertook" to import tenants from England to work their new lands). The Undertakers were also supposed to build new towns and provide for the defence of planted districts from attack.

As well as the former Geraldine estates (spread through the modern counties Limerick

County Limerick

It is thought that humans had established themselves in the Lough Gur area of the county as early as 3000 BC, while megalithic remains found at Duntryleague date back further to 3500 BC...

, Cork

County Cork

County Cork is a county in Ireland. It is located in the South-West Region and is also part of the province of Munster. It is named after the city of Cork . Cork County Council is the local authority for the county...

, Kerry

County Kerry

Kerry means the "people of Ciar" which was the name of the pre-Gaelic tribe who lived in part of the present county. The legendary founder of the tribe was Ciar, son of Fergus mac Róich. In Old Irish "Ciar" meant black or dark brown, and the word continues in use in modern Irish as an adjective...

and Tipperary

County Tipperary

County Tipperary is a county of Ireland. It is located in the province of Munster and is named after the town of Tipperary. The area of the county does not have a single local authority; local government is split between two authorities. In North Tipperary, part of the Mid-West Region, local...

) the survey took in the lands belonging to other families and clans that had supported the rebellions in south-west Cork and Kerry. However, the settlement here was rather piecemeal because the ruling clan — the MacCarthy Mór line — argued that the rebel landowners were their subordinates and therefore the land really belonged to them. Lands were therefore granted to some Undertakers and then taken away again when native lords like the MacCarthys appealed the dispossession of their dependants.

Other sectors of the plantation were equally chaotic. John Popham imported 70 tenants from Somerset

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

, only to find that the land had already been settled by another undertaker, and he was obliged to return them home. Nevertheless, 500,000 acres (2,000 km²) were planted with English colonists. It was hoped that the settlement would attract in the region of 15,000 colonists, but a report from 1589 showed that the undertakers had imported only in the region of 700 English tenants between them. It has been suggested that each tenant was the head of a household, and that he therefore represents 4-5 other people. This would put the English population in Munster at nearer to three or four thousand persons, but it was still substantially below the projected figure.

The Munster Plantation was supposed to produce compact defensible settlements, but in fact, the English settlers were spread in pockets across the province, wherever land had been confiscated. Initially the Undertakers were given detachments of English soldiers to protect them, but these were abolished in the 1590s. As a result, when the Nine Years War — an Irish rebellion against English rule — came to Munster in 1598, most of the settlers were chased off their lands without a fight. They took refuge in the province's walled towns or fled back to England. However when the rebellion was put down in 1601–03, the Plantation was re-constituted by the Governor of Munster, George Carew.

Ulster Plantation (1606 onwards)

Prior to its conquest in the Nine Years War of the 1590s, UlsterUlster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

was the most Gaelic part of Ireland and the only province that was completely outside English control. The war, of 1594–1603, ended with the surrender of the O’Neill and O’Donnell lords to the English crown, but was also a hugely costly and humiliating episode for the English government in Ireland. Moreover, in the short term it had been a failure, since the surrender terms given to the rebels were very generous, re-granting them much of their former lands, but under English law.

However, when Hugh O'Neill and the other rebel Earls left Ireland in 1607 (the so called Flight of the Earls

Flight of the Earls

The Flight of the Earls took place on 14 September 1607, when Hugh Ó Neill of Tír Eóghain, Rory Ó Donnell of Tír Chonaill and about ninety followers left Ireland for mainland Europe.-Background to the exile:...

) to seek Spanish help for a new rebellion, the Lord Deputy, Arthur Chichester, seized the opportunity to colonise the province and declared the lands of O’Neill, O’Donnell and their followers forfeit. Initially, Chichester planned a fairly modest plantation, including large grants to native Irish lords who had sided with the English during the war. However, this plan was interrupted by the rebellion of Cahir O’Doherty of Donegal

Donegal

Donegal or Donegal Town is a town in County Donegal, Ireland. Its name, which was historically written in English as Dunnagall or Dunagall, translates from Irish as "stronghold of the foreigners" ....

in 1608, a former ally of the English, who felt that he had not been fairly rewarded for his role in the war. The rebellion was swiftly put down and O’Doherty killed but it gave Chichester the justification for expropriating all native landowners in the province.

James VI of Scotland had become King of England in 1603, uniting those two crowns –also of course gaining possession of the Kingdom of Ireland

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

– an English possession. The Plantation of Ulster was sold to him as a joint "British", i.e. English and Scottish, venture to pacify and civilise Ulster. So at least half of the settlers would be Scots. Six counties were involved in the official plantation – Armagh

County Armagh

-History:Ancient Armagh was the territory of the Ulaid before the fourth century AD. It was ruled by the Red Branch, whose capital was Emain Macha near Armagh. The site, and subsequently the city, were named after the goddess Macha...

, Fermanagh

County Fermanagh

Fermanagh District Council is the only one of the 26 district councils in Northern Ireland that contains all of the county it is named after. The district council also contains a small section of County Tyrone in the Dromore and Kilskeery road areas....

, Cavan

County Cavan

County Cavan is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Cavan. Cavan County Council is the local authority for the county...

, Coleraine

County Coleraine

County Coleraine, called County of Colerain in the earliest documents was one of the counties of Ireland from 1585 to 1613. It was named after its intended county town, Coleraine...

, Donegal

County Donegal

County Donegal is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Donegal. Donegal County Council is the local authority for the county...

and Tyrone

County Tyrone

Historically Tyrone stretched as far north as Lough Foyle, and comprised part of modern day County Londonderry east of the River Foyle. The majority of County Londonderry was carved out of Tyrone between 1610-1620 when that land went to the Guilds of London to set up profit making schemes based on...

.

The plan for the plantation was determined by two factors, one was the wish to make sure the settlement could not be destroyed by rebellion as the first Munster plantation had been. This meant that, rather than settling the Planters in isolated pockets of land confiscated from convicted rebels, all of the land would be confiscated and then redistributed to create concentrations of British settlers around new towns and garrisons. What was more, the new landowners were explicitly banned from taking Irish tenants and had to import them from England and Scotland. The remaining Irish landowners were to be granted one quarter of the land in Ulster and the ordinary Irish population was supposed to be relocated to live near garrisons and Protestant churches. Moreover, the Planters were also barred from selling their lands to any Irishman.

The second major influence on the Plantation was the negotiation between various interest groups on the British side. The principal landowners were to be Undertakers, wealthy men from England and Scotland who undertook to import tenants from their own estates. They were granted around 3,000 acres (12 km²) each, on condition that they settle a minimum of 48 adult males (including at least 20 families) who had to be English-speaking

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

and Protestant. However, veterans of the war in Ireland (known as Servitors) and led by Arthur Chichester, successfully lobbied that they should be rewarded with land grants of their own. Since these former officers did not have enough private capital to fund the colonisation, their involvement was subsidised by the City of London

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

(the financial sector in London), who were also granted their own town (Derry

Derry

Derry or Londonderry is the second-biggest city in Northern Ireland and the fourth-biggest city on the island of Ireland. The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Irish name Doire or Doire Cholmcille meaning "oak-wood of Colmcille"...

, now officially named Londonderry although typically called Derry in general parlance) and lands. The final major recipient of lands was the Protestant Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

, which was granted all the churches and lands previously owned by the Roman Catholic church. It was intended that clerics from England and the Pale would convert the native population to Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

.

The plantation was a mixed success for the English. By the 1630s, there were 20,000 adult male English and Scottish settlers in Ulster, which meant that the total settler population could have been as high as 80,000. They formed local majorities of the population in the Finn

River Finn

The River Finn is a river that flows through County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland and County Tyrone in Northern Ireland. It rises in Lough Finn in County Donegal and flows east through a deep mountain valley to Ballybofey and Stranorlar and on to the confluence with the River Mourne at Lifford...

and Foyle

River Foyle

The River Foyle is a river in west Ulster in the northwest of Ireland, which flows from the confluence of the rivers Finn and Mourne at the towns of Lifford in County Donegal, Republic of Ireland, and Strabane in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. From here it flows to the City of Derry, where it...

valleys (around modern Derry and east Donegal

County Donegal

County Donegal is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Border Region and is also located in the province of Ulster. It is named after the town of Donegal. Donegal County Council is the local authority for the county...

) in north Armagh

County Armagh

-History:Ancient Armagh was the territory of the Ulaid before the fourth century AD. It was ruled by the Red Branch, whose capital was Emain Macha near Armagh. The site, and subsequently the city, were named after the goddess Macha...

and east Tyrone

County Tyrone

Historically Tyrone stretched as far north as Lough Foyle, and comprised part of modern day County Londonderry east of the River Foyle. The majority of County Londonderry was carved out of Tyrone between 1610-1620 when that land went to the Guilds of London to set up profit making schemes based on...

. Moreover, there had also been substantial settlement on unofficially planted lands in north Down, led by James Hamilton

James Hamilton, 1st Viscount Claneboye

James Hamilton, 1st Viscount Claneboye was a Scot who became owner of large tracts of land in County Down, Ireland, and founded a successful Protestant Scots settlement there several years before the Plantation of Ulster...

and Hugh Montgomery, and in south Antrim under Sir Randall MacDonnell. What was more, the settler population grew rapidly as just under half of the planters were women – a very high ratio compared to contemporary Spanish settlement in Latin America

Latin America

Latin America is a region of the Americas where Romance languages – particularly Spanish and Portuguese, and variably French – are primarily spoken. Latin America has an area of approximately 21,069,500 km² , almost 3.9% of the Earth's surface or 14.1% of its land surface area...

or English settlement in Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

and New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

.

However, the Irish population was neither removed nor Anglicised. In practise, the settlers did not stay on bad land, but clustered around towns and the best land. This meant that many English and Scottish landowners had to take Irish tenants, contrary to the terms of the plantation. In 1609, Chichester had deported 1300 former Irish soldiers from Ulster to serve in the Swedish Army

Swedish Army

The Swedish Army is one of the oldest standing armies in the world and a branch of the Swedish Armed Forces; it is in charge of land operations. General Sverker Göranson is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Army.- Organization :...

, but the province remained plagued with Irish bandits known as "wood-kerne" who attacked vulnerable settlers. It was said that English settlers were not safe a mile outside walled towns as native Tories plagued the forests and wolves roamed the countryside.

The attempted conversion of the Irish to Protestantism also had little effect, at first because the clerics imported were all English speakers, whereas the native population were usually monoglot speakers of Irish Gaelic

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

. Later, the Catholic Church made a determined effort to retain its followers among the native population.

Later plantations (1610–1641)

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

and Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

—in the early 17th century. The first of these took place in north county Wexford

County Wexford

County Wexford is a county in Ireland. It is part of the South-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Wexford. In pre-Norman times it was part of the Kingdom of Uí Cheinnselaig, whose capital was at Ferns. Wexford County Council is the local...

in 1610, where lands were confiscated from the MacMurrough-Kavanagh clan.

County Longford

County Longford is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Midlands Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford.Longford County Council is the local authority for the county...

, Leitrim

County Leitrim

County Leitrim is a county in Ireland. It is located in the West Region and is also part of the province of Connacht. It is named after the village of Leitrim. Leitrim County Council is the local authority for the county...

and north Tipperary

County Tipperary

County Tipperary is a county of Ireland. It is located in the province of Munster and is named after the town of Tipperary. The area of the county does not have a single local authority; local government is split between two authorities. In North Tipperary, part of the Mid-West Region, local...

.

To take one example of this policy: in 1621 King James I established his claims to the whole of Upper Ossory in County Laois

County Laois

County Laois is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Midlands Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It was formerly known as Queen's County until the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922. The county's name was formerly spelt as Laoighis and Leix. Laois County Council...

including the manor of Offerlane. James claimed royal inheritance (from the de Clare

De Clare

The de Clare family of Norman lords were associated with the Welsh Marches, Suffolk, Surrey, Kent and Ireland. They were descended from Richard fitz Gilbert, who accompanied William the Conqueror into England during the Norman conquest of England.-Origins:The Clare family descends from Gilbert...

family) at an inquisition held at Maryborough

Maryborough

Maryborough may refer to:* Maryborough, Queensland, a town in Australia** Electoral district of Maryborough, Queensland* Maryborough, Victoria, another town in Australia* The pre-1922 name of Port Laoise in the Republic of Ireland...

and instituted a plantation of the area in 1626. John FitzPatrick, Baron of Upper Ossory, refused to submit the manor of Castletown

Castletown

Castletown is a town geographically within the Malew parish of the Isle of Man but administered separately. Lying at the south of the island, it is the former Manx capital. The centre of town is dominated by Castle Rushen, a well-preserved castle.-History:...

to the plantation. In 1537 his ancestor, Brian MacGiollapadraig, agreed to surrender Upper Ossory to King Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

and was regranted the lordship under English law and in 1541 was made Baron of Upper Ossory. After John FitzPatrick's death in 1626 his son Florence continued this opposition to the plantation on his estates. However, the Fitzpatricks were eventually forced to concede a portion of their lands.

In Laois and Offally, the Tudor plantation had consisted of a chain of military garrisons, but in the new, more peaceful climate of the 17th century, it attracted large numbers of landowners, tenants and labourers. Prominent planters in Leinster in this period include Charles Coote, Adam Loftus and William Parsons.

In Munster, the peaceful first half of the 17th century saw thousands more English and Welsh settlers arrive in the province. There were many small plantations in Munster in this period, as Irish lords were required to forfeit up to one third of their estates in order to get their deeds to the remainder recognised by the English authorities. The settlers became concentrated in towns along the south coast — especially Youghal

Youghal

Youghal is a town in County Cork, Ireland. Sitting on the estuary of the River Blackwater, in the past it was militarily and economically important. Being built on the edge of a steep riverbank, the town has a distinctive long and narrow layout...

, Bandon

Bandon, County Cork

Bandon is a town in County Cork, Ireland. With a population of 5,822 as of census 2006, Bandon lies on the River Bandon between two hills. The name in Irish means "Bridge of the Bandon", a reference to the origin of the town as a crossing-point on the river. In 2004 Bandon celebrated its...

, Kinsale

Kinsale

Kinsale is a town in County Cork, Ireland. Located some 25 km south of Cork City on the coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon and has a population of 2,257 which increases substantially during the summer months when the tourist season is at its peak and...

and Cork city

Cork (city)

Cork is the second largest city in the Republic of Ireland and the island of Ireland's third most populous city. It is the principal city and administrative centre of County Cork and the largest city in the province of Munster. Cork has a population of 119,418, while the addition of the suburban...

. Famous English Undertakers of the Munster Plantation include Walter Raleigh

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh was an English aristocrat, writer, poet, soldier, courtier, spy, and explorer. He is also well known for popularising tobacco in England....

, Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and one of the greatest poets in the English...

, and Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork

Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork

Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork , also known as the Great Earl of Cork, was Lord Treasurer of the Kingdom of Ireland....

. The latter especially made huge fortunes out of amassing Irish lands and developing them for industry and agriculture.

In addition to the plantations, thousands of independent settlers arrived in Ireland in the early 17th century, from the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

as well as Britain. Many of them became chief tenants of Irish land-owners, others established themselves in the towns (especially Dublin) — notably as bankers and financiers. By 1641, there were calculated to be up to 125,000 Protestant settlers in Ireland, though they were still outnumbered by native Catholics by around 15 to 1.

Not all of the early 17th Century English Planters were Protestants. A considerable number of English Catholics settled in Ireland between 1603-1641 in part for economic reasons but also to escape persecution. This may seem paradoxical at first. However in the time of Elizabeth and James I the Catholics of England suffered a greater degree of persecution than English Catholics in Ireland. In England, Catholics were greatly outnumbered by Protestants and lived under constant fear of betrayal by their fellows. In Ireland however they could blend in with the local majority Catholic population in a way that was not possible in England. English Catholic planters were most common in County Kilkenny, where they may have made up half of all the English and Scottish planters to arrive in this region. Given this it is no surprise that the sons and grandsons of English planters played a major part in the politics of the Confederation of Kilkenny in the 1640s, most notably James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven

James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven

James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven was the son of Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven and his first wife, Elizabeth Barnham...

.

Plantations stayed off the political agenda until the accession of Thomas Wentworth

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford was an English statesman and a major figure in the period leading up to the English Civil War. He served in Parliament and was a supporter of King Charles I. From 1632 to 1639 he instituted a harsh rule as Lord Deputy of Ireland...

, a close advisor of Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, to the position of Lord Deputy of Ireland

Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the King's representative and head of the Irish executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and later the Kingdom of Ireland...

in 1632. Wentworth’s job was to raise revenue for Charles and to cement Royal control over Ireland — which meant, among other things, more plantations, both to raise money and to break the political power of the Irish Catholic gentry. Wentworth confiscated land in Wicklow

Wicklow

Wicklow) is the county town of County Wicklow in Ireland. Located south of Dublin on the east coast of the island, it has a population of 10,070 according to the 2006 census. The town is situated to the east of the N11 route between Dublin and Wexford. Wicklow is also connected to the rail...

and planned a full scale Plantation of Connacht

Connacht

Connacht , formerly anglicised as Connaught, is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the west of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for...

— where all Catholic landowners would lose between a half and a quarter of their estates. The local juries were intimidated into accepting Wentworth’s settlement and when a group of Connacht landowners complained to Charles I, Wentworth had them imprisoned. However, settlement only went ahead in County Sligo and County Roscommon

County Roscommon

County Roscommon is a county in Ireland. It is located in the West Region and is also part of the province of Connacht. It is named after the town of Roscommon. Roscommon County Council is the local authority for the county...

. Next, Wentworth surveyed the major Catholic landowners in Leinster

Leinster

Leinster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the east of Ireland. It comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Mide, Osraige and Leinster. Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the historic fifths of Leinster and Mide gradually merged, mainly due to the impact of the Pale, which straddled...

for similar treatment, including members of the powerful Butler dynasty. Wentworth’s plans were interrupted by the outbreak of the Bishops Wars in Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, which eventually led to Wentworth’s execution by the English Parliament and to civil war

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms formed an intertwined series of conflicts that took place in England, Ireland, and Scotland between 1639 and 1651 after these three countries had come under the "Personal Rule" of the same monarch...

in England and Ireland. His constant questioning of Catholic land titles was one of the major causes of the 1641 Rebellion and the principal reason why it was joined by Ireland’s wealthiest and most powerful Catholic families.

The 1641 Rebellion

In October 1641, after a bad harvest and in a threatening political climate, Phelim O'Neill launched a rebellion, hoping to rectify various grievances of Irish Catholic landowners. However, once the rebellion was underway, the resentment of the native Irish in Ulster boiled over into indiscriminate attacks on the settler population in the Irish Rebellion of 1641Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

. Irish Catholics attacked the plantations all around the country, but especially in Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

. English writers at the time put the Protestant victims at over 100,000 and William Petty

William Petty

Sir William Petty FRS was an English economist, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving Oliver Cromwell and Commonwealth in Ireland. He developed efficient methods to survey the land that was to be confiscated and given to Cromwell's soldiers...

, in his survey of the 1650s, estimated the death toll at around 30,000. More recent research, however, based on close examination of the depositions

Deposition (law)

In the law of the United States, a deposition is the out-of-court oral testimony of a witness that is reduced to writing for later use in court or for discovery purposes. It is commonly used in litigation in the United States and Canada and is almost always conducted outside of court by the...

of the Protestant refugees collected in 1642, suggests a figure of 4,000 settlers were killed directly and up to 12,000 who may have perished from disease or privation after being expelled from their homes.

The Irish Catholics formed their own government, Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland refers to the period of Irish self-government between the Rebellion of 1641 and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. During this time, two-thirds of Ireland was governed by the Irish Catholic Confederation, also known as the "Confederation of Kilkenny"...

, to fight the subsequent wars

Irish Confederate Wars

This article is concerned with the military history of Ireland from 1641-53. For the political context of this conflict, see Confederate Ireland....

, negotiating with Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, for, among other things, an end to the plantations and a partial reversal of the existing ones. The following ten years saw murderous fighting between the rival ethnic and religious blocks throughout Ireland until the Irish Catholics were finally crushed and the country occupied by the New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland refers to the conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in 1649...

in 1649 to 1653.

Ulster was worst hit by the wars, with massive loss of civilian life and mass displacement of people. The atrocities committed by both sides further poisoned the relationship between the settler and native communities in the province. Although peace was eventually restored to Ulster, the wounds opened in the plantation and civil war years were very slow to heal and arguably still fester in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

today.

In the 1641 Rebellion, the Munster Plantation was temporarily destroyed, just as it had been during the Nine Years War. Munster saw ten years of warfare between the planters and their descendants and the native Irish Catholics. However, the ethnic/religious divisions were less stark in Munster than in Ulster. Some of the earlier English Planters in Munster had been Roman Catholics and their descendants largely sided with the Irish in the 1640s. Conversely, some Irish noblemen who had converted to Protestantism - notably Earl Inchiquin, sided with the settler community.

Cromwellian land confiscation (1652)

The Irish Confederates had pinned their hopes on Royalist victory in the Wars of the Three KingdomsWars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms formed an intertwined series of conflicts that took place in England, Ireland, and Scotland between 1639 and 1651 after these three countries had come under the "Personal Rule" of the same monarch...

, so that they could cite their loyalty to Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

and force him into accepting their demands - including toleration for Catholicism, Irish self-government and an end to the Plantation policy. However, Charles’ Royalists

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

were defeated in the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

by the Parliamentarians

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

, who committed themselves to re-conquering Ireland and punishing those responsible for the rebellion of 1641. In 1649, Cromwell landed in Ireland with the New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

and by 1652, the conquest was all but complete. The English Parliament then published punitive terms of surrender for Catholics and Royalists in Ireland that included the mass confiscation of all Catholic owned land.

Cromwell held all Irish Catholics responsible for the rebellion of 1641 and said he would deal with them according to their "respective de-merits"- meaning sanctions varying from execution in worst cases, to partial land confiscation even for those who had taken no part in the wars. The Long Parliament

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was made on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and...

had been committed to mass confiscation of land in Ireland since 1642, when it passed the Adventurers Act

Adventurers Act

The Adventurers' Act is an Act of the Parliament of England, with the long title "An Act for the speedy and effectual reducing of the rebels in His Majesty's Kingdom of Ireland".-The main Act:...

, which raised loans secured on the Irish rebels' lands that were to be confiscated. The Act of Settlement 1652 stated that anyone who had held arms against the Parliament would forfeit their lands and that even those who had not would lose three quarters of their lands – being compensated with some other lands in Connacht

Connacht

Connacht , formerly anglicised as Connaught, is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the west of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for...

. In practice, those Protestants who had fought for the Royalists avoided confiscation by paying fines to the Commonwealth regime, but the Irish Catholic land-owning class was utterly destroyed. In some respects, what Cromwell had achieved was the logical conclusion of the plantation process.

The work was aided by the compilation of the Irish Civil Survey of 1654-5. The purpose of the survey was to secure information on the location, type, value and ownership of lands in the year 1641, before the outbreak of the Irish Rebellion of 1641

Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

. In all twenty-seven counties were surveyed and a survey produced for each. The Down Survey

Down Survey

The Down Survey, also known as the Civil Survey, refers to the mapping of Ireland carried out by William Petty, English scientist in 1655 and 1656....

of 1655-6 was a measured map survey, organised by Sir William Petty

William Petty

Sir William Petty FRS was an English economist, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving Oliver Cromwell and Commonwealth in Ireland. He developed efficient methods to survey the land that was to be confiscated and given to Cromwell's soldiers...

, of the lands confiscated.

Over 12,000 veterans of the New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

were given land in Ireland in place of their wages, which the Commonwealth was unable to pay. Many of these sold their land grants to other Protestants rather than settle in war-ravaged Ireland, but 7,500 soldiers did remain in the country. They were required to keep their weapons to act as a reserve militia in case of future rebellions. Taken together with the Merchant Adventurers, probably over 10,000 Parliamentarians settled in Ireland after the civil wars. Most of these were single men however and many of them married Irish women (although banned by law from doing so). Some of the Cromwellian soldiers therefore became integrated into Irish Catholic society. In addition to the Parliamentarians, thousands of Scottish Covenanter

Covenanter

The Covenanters were a Scottish Presbyterian movement that played an important part in the history of Scotland, and to a lesser extent in that of England and Ireland, during the 17th century...

soldiers, who had been stationed in Ulster during the war settled there permanently after its end.

Some Parliamentarians had argued that all the Irish should be deported to west of the Shannon

River Shannon

The River Shannon is the longest river in Ireland at . It divides the west of Ireland from the east and south . County Clare, being west of the Shannon but part of the province of Munster, is the major exception...

and replaced with English settlers. However, this would have required hundreds of thousands of English settlers willing to come to Ireland and such numbers of aspirant settlers just did not exist. Therefore, what actually happened was that a land-owning class of British Protestants was created, ruling over Irish Catholic tenants. A minority of the "Cromwellian" landowners were actually Parliamentarian soldiers or creditors. Most of them were pre-war Protestant settlers, who took the opportunity to attain confiscated lands. Before the wars, Catholics had owned 60% of the land in Ireland. During the Commonwealth period Catholic landownership fell to 8-9% and after some restitution in the Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

Act of Settlement 1662

Act of Settlement 1662

The Act of Settlement 1662 passed by the Irish Parliament in Dublin. It was a partial reversal of the Cromwellian Act of Settlement 1652, which punished Irish Catholics and Royalists for fighting against the English Parliament in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms by the wholesale confiscation of their...

, it rose to 20% again.

In Ulster, the Cromwellian period eliminated those native landowners who had survived the Ulster plantation. In Munster and Leinster, the mass confiscation of Catholic owned land after the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland refers to the conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in 1649...

, meant that English Protestants acquired almost all of the land holdings for the first time. In addition, some 12,000 Irish people were sold into slavery under the Commonwealth regime and another 34,000 went into exile, mostly in France or Spain.

Recent research has shown that although the native Irish land-owning class was subordinated in this period, it never totally disappeared, many of its members finding niches for themselves in trade or as chief tenants on their families’ ancestral lands.

Subsequent settlement

For the remainder of the 17th century, Irish Catholics tried to get the Cromwellian Act of Settlement reversed. They briefly achieved this under James IIJames II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

during the Williamite war in Ireland

Williamite war in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland—also called the Jacobite War in Ireland, the Williamite-Jacobite War in Ireland and in Irish as Cogadh an Dá Rí —was a conflict between Catholic King James II and Protestant King William of Orange over who would be King of England, Scotland and Ireland...

, but the Jacobite

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

defeat there led to another round of land confiscations. The 1680s and 90s saw another major wave of settlement in Ireland (though not another plantation). The new settlers were principally composed of Scots, tens of thousands of whom fled a famine in the lowlands and border regions of Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

to come to Ulster. It was at this point that Protestants and people of Scottish descent (who were mainly Presbyterians) became an absolute majority of the population in Ulster.

Another group established in Ireland at this time were French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

Huguenots, who had been expelled from France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes

Edict of Nantes

The Edict of Nantes, issued on 13 April 1598, by Henry IV of France, granted the Calvinist Protestants of France substantial rights in a nation still considered essentially Catholic. In the Edict, Henry aimed primarily to promote civil unity...

in 1685. Many of the Frenchmen were former soldiers, who had fought on the Williamite side in the Williamite war in Ireland

Williamite war in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland—also called the Jacobite War in Ireland, the Williamite-Jacobite War in Ireland and in Irish as Cogadh an Dá Rí —was a conflict between Catholic King James II and Protestant King William of Orange over who would be King of England, Scotland and Ireland...

. This community established themselves mainly in Dublin, where their communal graveyard can still be seen off St Stephen's Green. The numbers of this community may have reached 10,000

Long-term results

The Plantations had a profound impact on Ireland in several ways. The first was the destruction of the native ruling classes and their replacement with the Protestant AscendancyProtestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

, of Protestant landowners originating from Britain, and most of them from England. Their position was buttressed by the Penal Laws, which denied political and most land-owning rights to Catholics and to some extent to Presbyterians. The dominance of this class in Irish life persisted until the late 18th century, and it voted for the Act of Union

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

with Britain in 1800.

Republic of Ireland

Ireland , described as the Republic of Ireland , is a sovereign state in Europe occupying approximately five-sixths of the island of the same name. Its capital is Dublin. Ireland, which had a population of 4.58 million in 2011, is a constitutional republic governed as a parliamentary democracy,...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

is largely a result of the settlement patterns of the Plantations of the early 17th century. The descendants of the English and Scottish Protestant settlers largely favoured a continued link with Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

and after 1801 with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

, whereas the descendants of the native Irish Catholics wanted Irish independence. By 1922, Unionists were in the majority in four of the nine counties of Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

. Consequently, following the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty , officially called the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was a treaty between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and representatives of the secessionist Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of...

, these four counties – and two others in which they formed a sizeable minority – remained in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

to form Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

. This new state contained a sizable Catholic minority, many of whom claimed to be descendants of those dispossessed in the Plantations. The Troubles

The Troubles

The Troubles was a period of ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland which spilled over at various times into England, the Republic of Ireland, and mainland Europe. The duration of the Troubles is conventionally dated from the late 1960s and considered by many to have ended with the Belfast...

in Northern Ireland are therefore in some respects a continuation of the conflict arising from the plantations.

The Plantations also had a major cultural impact. Gaelic Irish culture was sidelined and English replaced Irish as the language of power and business. Although, by 1700, Irish

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

remained the majority language in Ireland, English was the dominant language for use in Parliament, the courts, and trade. In the next two centuries it was to advance westwards across the country until Irish suddenly collapsed after the Great Famine of the 1840s.

Finally, the plantations also radically altered Ireland’s ecology

Ecology

Ecology is the scientific study of the relations that living organisms have with respect to each other and their natural environment. Variables of interest to ecologists include the composition, distribution, amount , number, and changing states of organisms within and among ecosystems...

and physical appearance. In 1600, most of Ireland was heavily wooded, apart from the bogs. Most of the population lived in small townlands, many migrating seasonally to fresh pastures for their cattle. By 1700, Ireland’s native woodland had been decimated, having been intensively exploited by the new settlers for commercial ventures such as shipbuilding. Several native species such as the wolf had been hunted to extinction. Most of the settler population now lived in permanent towns or villages, although the Irish peasantry continued their traditional practices. Moreover, almost all of Ireland was now integrated into a market economy

Market economy

A market economy is an economy in which the prices of goods and services are determined in a free price system. This is often contrasted with a state-directed or planned economy. Market economies can range from hypothetically pure laissez-faire variants to an assortment of real-world mixed...

— although many of the poorer classes had no access to money, still paying their rents in kind

Payment in kind

Payment in kind refers to payment for goods or services with a medium other than legal tender ....

or in service.

See also

- English colonial empireEnglish colonial empireThe English colonial empire consisted of a variety of overseas territories colonized, conquered, or otherwise acquired by the former Kingdom of England between the late 16th and early 18th centuries....

- British colonization of the AmericasBritish colonization of the AmericasBritish colonization of the Americas began in 1607 in Jamestown, Virginia and reached its peak when colonies had been established throughout the Americas...

- Early Modern Ireland 1536-1691

- Protestant AscendancyProtestant AscendancyThe Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

- Down SurveyDown SurveyThe Down Survey, also known as the Civil Survey, refers to the mapping of Ireland carried out by William Petty, English scientist in 1655 and 1656....

-William PettyWilliam PettySir William Petty FRS was an English economist, scientist and philosopher. He first became prominent serving Oliver Cromwell and Commonwealth in Ireland. He developed efficient methods to survey the land that was to be confiscated and given to Cromwell's soldiers...

's survey of Irish land and population before the Cromwellian Plantations

Sources

- CANNY, Nicholas P., Making Ireland British 1580–1650, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001

- FORD & McCAFFERTY, The Origins of Sectarianism in Early Modern Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- LENNON, Colm, Sixteenth Century Ireland — The Incomplete Conquest, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. 1994

- LENIHAN, Padraig, Confederate Catholics at War, Cork: Cork University Press, 2000

- MCCARTHY, Daniel, The Life and Letter book of Florence McCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry, Dublin, 1867

- MACCARTHY-MORROGH, Michael, The Munster Plantation — English migration to Southern Ireland 1583–1641, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986

- SCOT-WHEELER, James, Cromwell in Ireland, New York, 1999