Petrov Affair

Encyclopedia

The Petrov Affair was a dramatic Cold War

spy incident in Australia

in April 1954, concerning Vladimir Petrov

, Third Secretary of the Soviet

embassy in Canberra

.

Petrov, despite his relatively junior diplomatic status, was a colonel in (what became in 1954) the KGB

Petrov, despite his relatively junior diplomatic status, was a colonel in (what became in 1954) the KGB

, the Soviet secret police, and his wife was an MVD officer. The Petrovs had been sent to the Canberra embassy in 1951 by the Soviet security chief, Lavrentiy Beria

. After Joseph Stalin

's death in March 1953, Beria had been arrested and shot by Stalin's successors, and Vladimir Petrov evidently feared that, if he returned to the Soviet Union, he would be purge

d as a "Beria man".

Petrov made contact with the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation

(ASIO) and offered to provide evidence of Soviet espionage in exchange for political asylum. The defection was arranged by Michael Bialoguski, a Polish doctor and musician, and part-time ASIO agent, who had cultivated Petrov for nearly two years, befriending him and taking him to visit prostitutes in Sydney's King's Cross

area. Bialoguski introduced Petrov to a senior ASIO officer, Ron Richards, who offered Petrov asylum plus £5,000 in exchange for all the documents he could bring with him from the embassy. Petrov defected on 3 April 1954.

Petrov did not tell his wife Evdokia

of his intention; apparently he planned to defect without her. After falsely claiming that Australian authorities had kidnapped Petrov, the MVD sent two couriers to Australia to fetch Evdokia Petrova. Word of this leaked out and there were violent anti-Communist demonstrations at Sydney Airport

as Evdokia Petrova was escorted by the KGB men to the aircraft. On the plane, on radioed instructions from Prime Minister Menzies, a flight attendant asked her if she was happy being escorted back to the USSR, but she did not give a clear answer. (She was wracked with indecision, as defection could have severe consequences for her family in the USSR.) Menzies

decided that he could not allow her to be removed in this way, and when the aircraft stopped for refuelling at Darwin, she was seized from the MVD men by ASIO officials. (In order to separate Petrova from the MVD, the ASIO officials confronted them on the grounds that they were carrying arms, which it was illegal to do on an aircraft.) The ASIO officials offered Petrova asylum, which she accepted, after phoning with her husband.

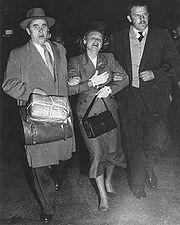

These dramatic events were reported around the world. The photos of Evdokia being rough-handled by KGB agents at Sydney Airport

and her agonised last-moment decision to defect with her husband, made while being bundled onto the plane at Darwin Airport that was due to take her back to the Soviet Union, have become iconic Australian images of the 1950s.

The affair grew more dramatic when Menzies told the House of Representatives

that Petrov had brought with him documents concerning Soviet espionage in Australia. He announced that a Royal Commission

would investigate the matter, the Royal Commission on Espionage. Petrov's documents were shown to the commission members, though they were never made public. The documents were alleged to provide evidence of an extensive Soviet spy ring in Australia, and named (among many others), two staff members of the leader of the Australian Labor Party

, Dr. H. V. Evatt

, during proceedings. Evatt, a former justice of the High Court of Australia

and the third President of the United Nations General Assembly

, appeared before the Royal Commission as attorney for his staff members. His cross-examination of a key ASIO operative transformed the commission's hearings and greatly perturbed the government. Almost immediately, the Royal Commission simply withdrew Evatt's leave to appear. Evatt alleged that the judges of the commission were biased towards the Menzies' government in the wake of this unprecedented denial of his right to appear.

As a result of the defections, the Australian embassy in Moscow was expelled and the USSR embassy in Canberra recalled. Diplomatic relations were not re-established until 1959.

. Evatt accused Menzies of having arranged the defections to coincide with the election, for the benefit of the ruling Liberal Party

.

According to some, partly as a result of the Petrov Affair, Menzies was successful at the election, which Labor had been widely expected to win. The Royal Commission continued for the rest of 1954 and uncovered some evidence of espionage for the Soviet Union by some members and supporters of the Communist Party of Australia

during and immediately after World War II

, but no-one was ever charged with an offence as a result of the commission's work and no major spy ring was uncovered. (No one was charged for various reasons: one was given immunity from prosecution, others who had handled documents had not technically broken the law, one was in Prague and remained there, and evidence against others could not be presented because it would reveal that Western intelligence services had broken Soviet codes.)

Evatt's loss of the election and his belief that Menzies had conspired with ASIO to contrive Petrov's defection led to criticism within the Labor Party of his decision to appear before the Royal Commission. He compounded this by writing to the Soviet Foreign Minister, Vyacheslav Molotov

, asking if allegations of Soviet espionage in Australia were true. When Molotov replied, denying the allegations, Evatt read the letter out in Parliament, inviting amazement and ridicule from his opponents.

Evatt's actions aroused the anger of the right wing of the Labor Party, influenced by the Catholic anti-Communism of B.A. Santamaria and his clandestine "Movement". Evatt came to believe that the Movement was also part of the conspiracy against him, and publicly denounced Santamaria and his supporters in October 1954, leading to a major split in the Labor Party

, which kept it out of power until 1972.

, who ghost-wrote their memoirs, published in 1956 as Empire of Fear.

They lived in relative obscurity for the rest of their lives. The press was formally requested by the Department of Defence, by way of a D-Notice, not to reveal their identities or whereabouts, but this was not always honoured. Vladimir died in 1991 and Evdokia in 2002.

(son of Gough Whitlam

, who was Labor Prime Minister at the time of publication) and John Stubbs. This book was written without access to classified documents.

Menzies always denied that he had had advance knowledge of Petrov's defection, although he did not deny that he had exploited it and Cold War anti-Communist sentiment. Colonel Charles Spry

, head of ASIO at the time, when interviewed after his retirement, maintained that, although it had taken some months of negotiations to bring about Petrov's defection, he had not told Menzies about these negotiations and that the timing of the defection had no connection to the elections.

In 1984, the ASIO files on Petrov and the records of the Royal Commission were made available to historians. In 1987, the historian Robert Manne

published The Petrov Affair: Politics and Espionage, which gave the first full account of the affair. He showed that Evatt's suspicions were unfounded, that Menzies and Spry had been telling the truth, that there had been no conspiracy, and that Evatt's own conduct had been mainly responsible for subsequent political events.

But Manne also showed that although there had been some Soviet espionage in Australia, there was no major Soviet spy ring, and that most of the documents given by Petrov to ASIO contained little more than political gossip which could have been compiled by any journalist. This included the notorious "Document J", which had been written by Rupert Lockwood, a member of the Communist Party of Australia

expressing his beliefs on the matter. Page 35 of the document sourced the information to Evatt's staffers, Fergan O’Sullivan, Albert Grundeman, and Allan Dalziel. Evatt insisted that page 35 was misinformation added specifically to damage the Australian Labor Party. He managed to prove that his staff have not authored the document. The Royal Commission

concluded that Document J was entirely Lockwood’s work.

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

spy incident in Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

in April 1954, concerning Vladimir Petrov

Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov (diplomat)

Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov was a member of the Soviet Union's clandestine services who became famous in 1954 for his defection to Australia.-Early life:...

, Third Secretary of the Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

embassy in Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

.

History

KGB

The KGB was the commonly used acronym for the . It was the national security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 until 1991, and was the premier internal security, intelligence, and secret police organization during that time.The State Security Agency of the Republic of Belarus currently uses the...

, the Soviet secret police, and his wife was an MVD officer. The Petrovs had been sent to the Canberra embassy in 1951 by the Soviet security chief, Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was a Georgian Soviet politician and state security administrator, chief of the Soviet security and secret police apparatus under Joseph Stalin during World War II, and Deputy Premier in the postwar years ....

. After Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's death in March 1953, Beria had been arrested and shot by Stalin's successors, and Vladimir Petrov evidently feared that, if he returned to the Soviet Union, he would be purge

Purge

In history, religion, and political science, a purge is the removal of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, from another organization, or from society as a whole. Purges can be peaceful or violent; many will end with the imprisonment or exile of those purged,...

d as a "Beria man".

Petrov made contact with the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation

Australian Security Intelligence Organisation

The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation is Australia's national security service, which is responsible for the protection of the country and its citizens from espionage, sabotage, acts of foreign interference, politically-motivated violence, attacks on the Australian defence system, and...

(ASIO) and offered to provide evidence of Soviet espionage in exchange for political asylum. The defection was arranged by Michael Bialoguski, a Polish doctor and musician, and part-time ASIO agent, who had cultivated Petrov for nearly two years, befriending him and taking him to visit prostitutes in Sydney's King's Cross

Kings Cross, New South Wales

Kings Cross is an inner-city locality of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately 2 kilometres east of the Sydney central business district, in the local government area of the City of Sydney...

area. Bialoguski introduced Petrov to a senior ASIO officer, Ron Richards, who offered Petrov asylum plus £5,000 in exchange for all the documents he could bring with him from the embassy. Petrov defected on 3 April 1954.

Petrov did not tell his wife Evdokia

Evdokia Petrova

Evdokia Alexeyevna Petrova was a Russian spy in Australia in the 1950s. She was the wife of Vladimir Petrov, and came to national prominence during the Petrov Affair....

of his intention; apparently he planned to defect without her. After falsely claiming that Australian authorities had kidnapped Petrov, the MVD sent two couriers to Australia to fetch Evdokia Petrova. Word of this leaked out and there were violent anti-Communist demonstrations at Sydney Airport

Sydney Airport

Sydney Airport may refer to:* Sydney Airport, also known as Kingsford Smith International Airport, in Sydney, Australia* Sydney/J.A. Douglas McCurdy Airport, in Nova Scotia, Canada...

as Evdokia Petrova was escorted by the KGB men to the aircraft. On the plane, on radioed instructions from Prime Minister Menzies, a flight attendant asked her if she was happy being escorted back to the USSR, but she did not give a clear answer. (She was wracked with indecision, as defection could have severe consequences for her family in the USSR.) Menzies

Robert Menzies

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, , Australian politician, was the 12th and longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia....

decided that he could not allow her to be removed in this way, and when the aircraft stopped for refuelling at Darwin, she was seized from the MVD men by ASIO officials. (In order to separate Petrova from the MVD, the ASIO officials confronted them on the grounds that they were carrying arms, which it was illegal to do on an aircraft.) The ASIO officials offered Petrova asylum, which she accepted, after phoning with her husband.

These dramatic events were reported around the world. The photos of Evdokia being rough-handled by KGB agents at Sydney Airport

Sydney Airport

Sydney Airport may refer to:* Sydney Airport, also known as Kingsford Smith International Airport, in Sydney, Australia* Sydney/J.A. Douglas McCurdy Airport, in Nova Scotia, Canada...

and her agonised last-moment decision to defect with her husband, made while being bundled onto the plane at Darwin Airport that was due to take her back to the Soviet Union, have become iconic Australian images of the 1950s.

The affair grew more dramatic when Menzies told the House of Representatives

Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia; it is the lower house; the upper house is the Senate. Members of Parliament serve for terms of approximately three years....

that Petrov had brought with him documents concerning Soviet espionage in Australia. He announced that a Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

would investigate the matter, the Royal Commission on Espionage. Petrov's documents were shown to the commission members, though they were never made public. The documents were alleged to provide evidence of an extensive Soviet spy ring in Australia, and named (among many others), two staff members of the leader of the Australian Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

, Dr. H. V. Evatt

H. V. Evatt

Herbert Vere Evatt, QC KStJ , was an Australian jurist, politician and writer. He was President of the United Nations General Assembly in 1948–49 and helped draft the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights...

, during proceedings. Evatt, a former justice of the High Court of Australia

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

and the third President of the United Nations General Assembly

President of the United Nations General Assembly

The President of the United Nations General Assembly is a position voted for by representatives in the United Nations General Assembly on a yearly basis.- Election :...

, appeared before the Royal Commission as attorney for his staff members. His cross-examination of a key ASIO operative transformed the commission's hearings and greatly perturbed the government. Almost immediately, the Royal Commission simply withdrew Evatt's leave to appear. Evatt alleged that the judges of the commission were biased towards the Menzies' government in the wake of this unprecedented denial of his right to appear.

As a result of the defections, the Australian embassy in Moscow was expelled and the USSR embassy in Canberra recalled. Diplomatic relations were not re-established until 1959.

Political Repercussions

The defections came shortly before the 1954 federal electionAustralian federal election, 1954

Federal elections were held in Australia on 29 May 1954. All 121 seats in the House of Representatives were up for election, no Senate election took place...

. Evatt accused Menzies of having arranged the defections to coincide with the election, for the benefit of the ruling Liberal Party

Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Founded a year after the 1943 federal election to replace the United Australia Party, the centre-right Liberal Party typically competes with the centre-left Australian Labor Party for political office...

.

According to some, partly as a result of the Petrov Affair, Menzies was successful at the election, which Labor had been widely expected to win. The Royal Commission continued for the rest of 1954 and uncovered some evidence of espionage for the Soviet Union by some members and supporters of the Communist Party of Australia

Communist Party of Australia

The Communist Party of Australia was founded in 1920 and dissolved in 1991; it was succeeded by the Socialist Party of Australia, which then renamed itself, becoming the current Communist Party of Australia. The CPA achieved its greatest political strength in the 1940s and faced an attempted...

during and immediately after World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, but no-one was ever charged with an offence as a result of the commission's work and no major spy ring was uncovered. (No one was charged for various reasons: one was given immunity from prosecution, others who had handled documents had not technically broken the law, one was in Prague and remained there, and evidence against others could not be presented because it would reveal that Western intelligence services had broken Soviet codes.)

Evatt's loss of the election and his belief that Menzies had conspired with ASIO to contrive Petrov's defection led to criticism within the Labor Party of his decision to appear before the Royal Commission. He compounded this by writing to the Soviet Foreign Minister, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

, asking if allegations of Soviet espionage in Australia were true. When Molotov replied, denying the allegations, Evatt read the letter out in Parliament, inviting amazement and ridicule from his opponents.

Evatt's actions aroused the anger of the right wing of the Labor Party, influenced by the Catholic anti-Communism of B.A. Santamaria and his clandestine "Movement". Evatt came to believe that the Movement was also part of the conspiracy against him, and publicly denounced Santamaria and his supporters in October 1954, leading to a major split in the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party split of 1955

The Australian Labor Party split of 1955 was a splintering of the Australian Labor Party along sectarian and ideological lines in the mid 1950s...

, which kept it out of power until 1972.

Fate of the Petrovs

The Petrovs, having been given political asylum, were eventually settled in suburban Melbourne under the names Sven and Maria Allyson, and given a pension. Prior to this, they spent an 18-month period in a safe house in Palm Beach, Sydney, with the then ASIO officer Michael ThwaitesMichael Thwaites

Michael Rayner Thwaites, AO was an Australian academic, poet, intelligence officer, and activist for Moral Rearmament.-Early life and education:...

, who ghost-wrote their memoirs, published in 1956 as Empire of Fear.

They lived in relative obscurity for the rest of their lives. The press was formally requested by the Department of Defence, by way of a D-Notice, not to reveal their identities or whereabouts, but this was not always honoured. Vladimir died in 1991 and Evdokia in 2002.

Verdict of history

The belief that there had been a "Petrov conspiracy" became an article of faith in the Labor Party and on the left generally for many years, although even pro-Labor historians acknowledged that Evatt's eccentric conduct had contributed greatly to the Labor split. The "left" version of the Petrov story was given in 1974 in Nest of Traitors: The Petrov Affair, by Nicholas WhitlamNicholas Whitlam

Nicholas Richard Whitlam born 6 December 1945, is an Australian businessman, the son of former Prime Minister Edward Gough Whitlam and Margaret Whitlam. He first became publicly prominent in 1981 when he was appointed chief executive of the State Bank of New South Wales...

(son of Gough Whitlam

Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam, AC, QC , known as Gough Whitlam , served as the 21st Prime Minister of Australia. Whitlam led the Australian Labor Party to power at the 1972 election and retained government at the 1974 election, before being dismissed by Governor-General Sir John Kerr at the climax of the...

, who was Labor Prime Minister at the time of publication) and John Stubbs. This book was written without access to classified documents.

Menzies always denied that he had had advance knowledge of Petrov's defection, although he did not deny that he had exploited it and Cold War anti-Communist sentiment. Colonel Charles Spry

Charles Spry

Brigadier Sir Charles Chambers Fowell Spry, CBE, DSO was an Australian soldier, who from 1950 to 1970 was the second Director-General of Security, the head of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation .-Early life:...

, head of ASIO at the time, when interviewed after his retirement, maintained that, although it had taken some months of negotiations to bring about Petrov's defection, he had not told Menzies about these negotiations and that the timing of the defection had no connection to the elections.

In 1984, the ASIO files on Petrov and the records of the Royal Commission were made available to historians. In 1987, the historian Robert Manne

Robert Manne

Robert Manne is a professor of politics at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.Born in Melbourne, Manne's earliest political consciousness was formed by the fact that his parents were Jewish refugees from Europe and his grandparents were victims of the Holocaust...

published The Petrov Affair: Politics and Espionage, which gave the first full account of the affair. He showed that Evatt's suspicions were unfounded, that Menzies and Spry had been telling the truth, that there had been no conspiracy, and that Evatt's own conduct had been mainly responsible for subsequent political events.

But Manne also showed that although there had been some Soviet espionage in Australia, there was no major Soviet spy ring, and that most of the documents given by Petrov to ASIO contained little more than political gossip which could have been compiled by any journalist. This included the notorious "Document J", which had been written by Rupert Lockwood, a member of the Communist Party of Australia

Communist Party of Australia

The Communist Party of Australia was founded in 1920 and dissolved in 1991; it was succeeded by the Socialist Party of Australia, which then renamed itself, becoming the current Communist Party of Australia. The CPA achieved its greatest political strength in the 1940s and faced an attempted...

expressing his beliefs on the matter. Page 35 of the document sourced the information to Evatt's staffers, Fergan O’Sullivan, Albert Grundeman, and Allan Dalziel. Evatt insisted that page 35 was misinformation added specifically to damage the Australian Labor Party. He managed to prove that his staff have not authored the document. The Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

concluded that Document J was entirely Lockwood’s work.

Further reading

- Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, Empire of Fear, Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1956 (these memoirs were ghost-written for the Petrovs by the then ASIO officer Michael ThwaitesMichael ThwaitesMichael Rayner Thwaites, AO was an Australian academic, poet, intelligence officer, and activist for Moral Rearmament.-Early life and education:...

) - Nicholas Whitlam and John Stubbs, Nest of Traitors: The Petrov Affair, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1974

- Michael Thwaites, Truth Will Out: ASIO and the Petrovs, William Collins, Sydney, 1980

- Robert Manne, The Petrov Affair: Politics and Espionage, Pergamon Press, Sydney, 1987

- Ursula DubosarskyUrsula DubosarskyUrsula Dubosarsky is an Australian writer of fiction and non-fiction for children and young adults. She has won nine national literary prizes, including five NSW Premier's Literary Awards, more than any other writer in the Awards' 30 year history...

, The Red Shoe, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2006 - Andrew Croome, Document Z, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2009

External links

- Mrs Petrov's death brings bizarre affair to end - an article by Robert Manne in The AgeThe AgeThe Age is a daily broadsheet newspaper, which has been published in Melbourne, Australia since 1854. Owned and published by Fairfax Media, The Age primarily serves Victoria, but is also available for purchase in Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and border regions of South Australia and...

newspaper - Neely F 2010, Menzies and the Petrov Affair, Clio History Journal.