Peasants' Revolt

Encyclopedia

History of England

The history of England concerns the study of the human past in one of Europe's oldest and most influential national territories. What is now England, a country within the United Kingdom, was inhabited by Neanderthals 230,000 years ago. Continuous human habitation dates to around 12,000 years ago,...

. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the best-documented popular rebellion

Rebellion

Rebellion, uprising or insurrection, is a refusal of obedience or order. It may, therefore, be seen as encompassing a range of behaviors aimed at destroying or replacing an established authority such as a government or a head of state...

to have occurred during medieval times. The names of some of its leaders, John Ball

John Ball (priest)

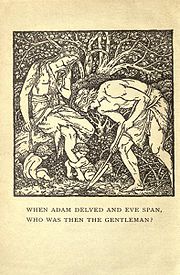

John Ball was an English Lollard priest who took a prominent part in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. In that year, Ball gave a sermon in which he asked the rhetorical question, "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?".-Biography:Little is known of Ball's early years. He lived in...

, Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler

Walter "Wat" Tyler was a leader of the English Peasants' Revolt of 1381.-Early life:Knowledge of Tyler's early life is very limited, and derives mostly through the records of his enemies. Historians believe he was born in Essex, but are not sure why he crossed the Thames Estuary to Kent...

and Jack Straw

Jack Straw (rebel leader)

For other uses, see Jack Straw Jack Straw was one of the three leaders of the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, a major event in the history of England.-Biography:Little is known of the Rising's leaders. It been suggested that Jack Straw may have been a preacher...

, are still familiar in popular culture

Popular culture

Popular culture is the totality of ideas, perspectives, attitudes, memes, images and other phenomena that are deemed preferred per an informal consensus within the mainstream of a given culture, especially Western culture of the early to mid 20th century and the emerging global mainstream of the...

, although little is known of them.

The revolt later came to be seen as a mark of the beginning of the end of serfdom

Serfdom

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century...

in medieval England, although the revolt itself was a failure. It increased awareness in the upper classes of the need for the reform of feudalism

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

in England and the appalling misery felt by the lower classes as a result of their enforced near-slavery

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

.

Poll tax

The revolt was precipitated by King Richard II'sRichard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

heavy-handed attempts to enforce the third medieval poll tax

Taxation in medieval England

Taxation in medieval England was the system of raising money for royal and governmental expenses. During the Anglo-Saxon period, the main forms of taxation were land taxes, although custom duties and fees to mint coins were also imposed. The most important tax of the late Anglo-Saxon period was the...

, first levied in 1377 supposedly to finance military campaigns overseas. The third poll tax was not levied at a flat rate (as in 1377) nor according to schedule (as in 1379); instead, it allowed some of the poor to pay a reduced rate, while others who were equally poor had to pay the full tax, prompting calls of injustice. The tax was set at three groats (equivalent to 12 pence or one shilling), compared with the 1377 rate of one groat (four pence). The youth of King Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

(aged only 14) was another reason for the uprising: a group of unpopular men dominated his government. These included John of Gaunt (the Duke of Lancaster), Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury, also called Simon Theobald of Sudbury and Simon of Sudbury was Bishop of London from 1361 to 1375, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1375 until his death, and in the last year of his life Lord Chancellor of England....

(Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

and Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, who was the figurehead to what many then saw as a corrupt church) and Sir Robert Hales

Robert Hales

Sir Robert Hales, also called Robert de Hales, was born about 1325 in Hales Place, High Halden, Kent, the son of Nicholas Hales.In 1372 Robert Hales became the Lord/Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitallers of England. Richard II appointed him Lord High Treasurer, so he was responsible for collecting...

(the Lord Treasurer, responsible for the poll tax). Many saw them as corrupt officials, trying to exploit the weakness of the king.

Labour shortage

The Black DeathBlack Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

that ravaged England in 1348 to 1350 had greatly reduced the labour force, and, consequently, the surviving labourers could demand higher wages and fewer hours of work. Some asked for their freedom. They often got what they asked for: the lords of the manors were desperate for people to farm their land and tend their animals. Then, in 1351, King Edward III summoned parliament to pass the Statute of Labourers. The statute attempted to curb the demands for better terms of employment by pegging wages to pre-plague levels and restricting the mobility of labour; however, the probable effect was that labourers employed by lords were effectively exempted, while labourers working for other employers, both artisans and more substantial peasants, were liable to be fined or held in the stocks. The enforcement of the new law angered the peasants greatly and formed another reason for the revolt.

Triggering

Incidents in the Essex villages of FobbingFobbing

Fobbing is a small village in Thurrock, Essex, England and one of Thurrock's traditional parishes. It is located between Basildon and Corringham, and is also close to Stanford-le-Hope....

and Brentwood

Brentwood, Essex

Brentwood is a town and the principal settlement of the Borough of Brentwood, in the county of Essex in the east of England. It is located in the London commuter belt, 20 miles east north-east of Charing Cross in London, and near the M25 motorway....

triggered the uprising. On 30 May 1381, John or Thomas Bampton attempted to collect the poll tax from villagers at Fobbing. The villagers, led by Thomas Baker

Thomas Baker (Peasants' Revolt leader)

Thomas Baker, an English landowner, was one of the leaders who initiated the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.Thomas Baker's holding was "Pokattescroft alias Bakerescroft" in Fobbing...

, a local landowner, told Bampton that they would give him nothing, and he was forced to leave the village empty-handed. Robert Belknap (Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas

Court of Common Pleas (England)

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century after splitting from the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common...

) was sent to investigate the incident and to punish the offenders. On 2 June, he was attacked at Brentwood. By this time, the violent discontent had spread, and the counties of Essex and Kent were in full revolt. Soon people moved on London in an armed uprising.

First protests

In June 1381, Kentish rebels formed behind Wat Tyler and marched on London to join the Essex contingent. When the Kentish rebels arrived at BlackheathBlackheath, London

Blackheath is a district of South London, England. It is named from the large open public grassland which separates it from Greenwich to the north and Lewisham to the west...

on 12 June, the renegade Lollard priest, John Ball

John Ball (priest)

John Ball was an English Lollard priest who took a prominent part in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. In that year, Ball gave a sermon in which he asked the rhetorical question, "When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?".-Biography:Little is known of Ball's early years. He lived in...

, preached a sermon including the famous question that has echoed down the centuries: "When Adam

Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve were, according to the Genesis creation narratives, the first human couple to inhabit Earth, created by YHWH, the God of the ancient Hebrews...

delved and Eve

Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve were, according to the Genesis creation narratives, the first human couple to inhabit Earth, created by YHWH, the God of the ancient Hebrews...

span, who was then the gentleman

Gentleman

The term gentleman , in its original and strict signification, denoted a well-educated man of good family and distinction, analogous to the Latin generosus...

?" The following day, the rebels, encouraged by the sermon, crossed London Bridge

London Bridge

London Bridge is a bridge over the River Thames, connecting the City of London and Southwark, in central London. Situated between Cannon Street Railway Bridge and Tower Bridge, it forms the western end of the Pool of London...

into the heart of the city. Meanwhile the "Men of Essex" had gathered with Jack Straw at Great Baddow

Great Baddow

Great Baddow is an urban village in the Chelmsford borough of Essex, England. It is close to the county town, Chelmsford and, with a population of over 13,000, is one of the largest villages in the country....

and had marched on London, arriving at Stepney

Stepney

Stepney is a district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in London's East End that grew out of a medieval village around St Dunstan's church and the 15th century ribbon development of Mile End Road...

. Instead of a full-scale riot, there were only systematic attacks on certain properties, many of them associated with John of Gaunt and/or the Hospitaller Order

Knights Hospitaller

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta , also known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta , Order of Malta or Knights of Malta, is a Roman Catholic lay religious order, traditionally of military, chivalrous, noble nature. It is the world's...

. On 14 June, the rebels are reputed to have been met by the young king himself, and, led by Richard of Wallingford

Richard of Wallingford (constable)

Richard of Wallingford , constable of Wallingford Castle and landowner in St Albans, played a key part in the English peasants' revolt of 1381. Though clearly not a peasant, he helped organise Wat Tyler’s campaign, and was involved in presenting the rebels’ petition to Richard II...

, to have presented him with a series of demands, including the dismissal of some of his more unpopular ministers and the effective abolition of serfdom. One of the more intriguing demands of the peasants was "that there should be no law within the realm save the law of Winchester". This may refer to the statutes of the Charter of Winchester (1251), though it is sometimes considered to be a reference to the more equitable days of King Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

, when Winchester

Winchester

Winchester is a historic cathedral city and former capital city of England. It is the county town of Hampshire, in South East England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government district, and is located at the western end of the South Downs, along the course of...

was the capital of England.

Storming the Tower of London

At the same time, a group of rebels stormed the Tower of LondonTower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

and summarily executed those hiding there, including the Lord Chancellor

Lord Chancellor

The Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, or Lord Chancellor, is a senior and important functionary in the government of the United Kingdom. He is the second highest ranking of the Great Officers of State, ranking only after the Lord High Steward. The Lord Chancellor is appointed by the Sovereign...

(Simon of Sudbury

Simon Sudbury

Simon Sudbury, also called Simon Theobald of Sudbury and Simon of Sudbury was Bishop of London from 1361 to 1375, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1375 until his death, and in the last year of his life Lord Chancellor of England....

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, who was particularly associated with the poll tax), and the Lord Treasurer (Robert de Hales

Robert Hales

Sir Robert Hales, also called Robert de Hales, was born about 1325 in Hales Place, High Halden, Kent, the son of Nicholas Hales.In 1372 Robert Hales became the Lord/Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitallers of England. Richard II appointed him Lord High Treasurer, so he was responsible for collecting...

, the Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitallers of England

Knights Hospitaller

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta , also known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta , Order of Malta or Knights of Malta, is a Roman Catholic lay religious order, traditionally of military, chivalrous, noble nature. It is the world's...

). The Savoy Palace

Savoy Palace

The Savoy Palace was considered the grandest nobleman's residence of medieval London, until it was destroyed in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. It fronted the Strand, on the site of the present Savoy Theatre and the Savoy Hotel that memorialise its name...

of the king's uncle John of Gaunt was one of the London buildings destroyed by the rioters.

Smithfield

Smithfield, London

Smithfield is an area of the City of London, in the ward of Farringdon Without. It is located in the north-west part of the City, and is mostly known for its centuries-old meat market, today the last surviving historical wholesale market in Central London...

on the following day, further negotiations with the king were arranged, but, on this occasion, the meeting did not go according to plan. Wat Tyler rode ahead to talk to the king and his party. Tyler, it is alleged by the king's chroniclers, behaved most belligerently and dismounted his horse and called for a drink most rudely. In the ensuing dispute, Tyler (supposedly) drew his dagger, and William Walworth

William Walworth

Sir William Walworth , was twice Lord Mayor of London . He is best known for killing Wat Tyler.His family came from Durham...

, the Lord Mayor of London, drew his sword and attacked Tyler, mortally wounding him in the neck; Sir John Cavendish

John Cavendish

Sir John Cavendish of Cavendish came from Cavendish, Suffolk, England. He and the village gave the name Cavendish to the aristocratic families, of the Dukedoms of Devonshire, Newcastle and Portland.-Biography:...

, one of the King's knights, drew his sword and ran it through Tyler's stomach, killing him almost instantly. Seeing him surrounded by the King's entourage, the rebel army was in uproar, but King Richard, seizing the opportunity, rode forth and shouted, "You shall have no captain but me," a statement left deliberately ambiguous to defuse the situation. He promised the rebels that all was well, that Tyler had been knighted, and that their demands would be met—they were to march to St John's Fields

St John's Fields

St John's Fields, London were fields owned by the church of St John of Clerkenwell and were used as a gathering point outside the city walls of medieval London.In 1381 the rebels involved with the Peasants' Revolt marched to the fields to meet Wat Tyler...

, where Wat Tyler would meet them. This they duly did, but the king broke his promise. The nobles quickly re-established their control with the help of a hastily organised militia of 7000, and most of the other leaders were pursued, captured and executed, including John Ball and Jack Straw. Following the collapse of the revolt, the king's concessions were quickly revoked. Those involved hastened to dissociate themselves in the months that followed.

The Peasants' Revolt outside London

Although the most significant events took place in the capital, there were violent encounters throughout England, particularly in East AngliaNorfolk

The revolt broke out in 14 June and quickly spread across the county. It was suppressed by the Bishop of Norwich, Henry le Despenser at the Battle of North WalshamBattle of North Walsham

The Battle of North Walsham was a mediaeval battle fought on 25 or 26 June 1381, near the town of North Walsham in the English county of Norfolk, in which a large group of rebellious local peasants was confronted by the heavily armed forces of Henry le Despenser, Bishop of Norwich...

on 25 or 26 June, when the local leader of the revolt, Geoffrey Litster, was captured and executed.

Conclusion

Despite its modern name, participation in the Peasants' Revolt was not confined to serfs or even to the lower classes. The peasants received help from members of the noble classes—one example being William Tonge, a substantial aldermanAlderman

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members themselves rather than by popular vote, or a council...

, who opened the London city gate through which the masses streamed on the night of 12 June. However this is debatable; the actions of individuals like Tonge could be ascribed to fear and panic rather than rational persuasion by the rebels.

Although the revolt did not succeed in its stated aims, it did succeed in showing the nobles that the peasants were dissatisfied and that they were capable of wreaking havoc. In the longer term, the revolt helped to form a radical tradition in British politics (a development explained by Christopher Hampton, see further reading). After the revolt, the term poll tax was no longer used, although English governments continued to collect broadly similar taxes until the 17th century. The Community Charge

Community Charge

The Community Charge, popularly known as the "poll tax", was a system of taxation introduced in replacement of the rates to part fund local government in Scotland from 1989, and England and Wales from 1990. It provided for a single flat-rate per-capita tax on every adult, at a rate set by the...

, introduced 600 years after the Peasants' Revolt, was popularly known as the poll tax (particularly by its opponents).

Literary mention

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

mentions Jack Straw

Jack Straw (rebel leader)

For other uses, see Jack Straw Jack Straw was one of the three leaders of the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, a major event in the history of England.-Biography:Little is known of the Rising's leaders. It been suggested that Jack Straw may have been a preacher...

, one of the leaders of the revolt, in his satiric The Nun's Priest's Tale in The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales is a collection of stories written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer at the end of the 14th century. The tales are told as part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims as they travel together on a journey from Southwark to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at...

.

Froissart's Chronicles

Froissart's Chronicles

Froissart's Chronicles was written in French by Jean Froissart. It covers the years 1322 until 1400 and describes the conditions that created the Hundred Years' War and the first fifty years of the conflict...

devotes 20 pages to the revolt.

The revolt is featured prominently in the climax of Anya Seton

Anya Seton

Anya Seton was the pen name of Ann Seton, an American author of historical romances.-Biography:...

's historical novel, Katherine

Katherine (novel)

Anya Seton's Katherine is a historical novel based largely on fact. It tells the story of the historically important love affair between the titular Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the third surviving son of King Edward III...

(1954). The main character, Katherine Swynford

Katherine Swynford

Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster , née Roet , was the daughter of Sir Payne Roet , originally a Flemish herald from County of Hainaut, later...

, survives the destruction of Savoy Palace

Savoy Palace

The Savoy Palace was considered the grandest nobleman's residence of medieval London, until it was destroyed in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. It fronted the Strand, on the site of the present Savoy Theatre and the Savoy Hotel that memorialise its name...

.

John Gower

John Gower

John Gower was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is remembered primarily for three major works, the Mirroir de l'Omme, Vox Clamantis, and Confessio Amantis, three long poems written in French, Latin, and English respectively, which...

, a friend of Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

, saw the peasants as unjustified in their cause. In his Vox Clamantis

Vox Clamantis

Vox Clamantis is a Latin poem of around 10,000 lines in elegiac verse by John Gower that recounts the events and tragedy of the 1381 Peasants' Rising. The poem takes aim at the corruption of society and laments the rise of evil...

, he sees the peasant action as the work of the Anti-Christ and a sign of evil prevailing over virtue, writing, "...according to their foolish ideas there would be no lords, but only kings and peasants."

William Morris

William Morris

William Morris 24 March 18343 October 1896 was an English textile designer, artist, writer, and socialist associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the English Arts and Crafts Movement...

described the revolt in A Dream of John Ball (1888).

"Wat Tyler," a song written by Ralph McTell

Ralph McTell

Ralph McTell is an English singer-songwriter and acoustic guitar player who has been an influential figure on the UK folk music scene since the 1960s....

and Simon Nicol

Simon Nicol

Simon John Breckenridge Nicol is a guitarist, singer, multi-instrumentalist and record producer. He was a founder member of British folk rock, or electric folk group Fairport Convention and is the only founding member still in the band...

and performed by Fairport Convention

Fairport Convention

Fairport Convention are an English folk rock and later electric folk band, formed in 1967 who are still recording and touring today. They are widely regarded as the most important single group in the English folk rock movement...

, is about the revolt.

Further reading

- R. B. Dobson, editor (2002), The Peasants' Revolt of 1381 (History in Depth), ISBN 0-333-25505-4; a collection of source materials

- Alastair Dunn (2002), The Great Rising of 1381: The Peasant's Revolt and England's Failed Revolution, ISBN 0-7524-2323-1

- Charles OmanCharles OmanSir Charles William Chadwick Oman was a British military historian of the early 20th century. His reconstructions of medieval battles from the fragmentary and distorted accounts left by chroniclers were pioneering...

(1906), The Great Revolt of 1381; a classic account - Andrew GodsellAndrew GodsellAndrew Godsell is a British writer, born in 1964 at Aldershot, in Hampshire.- Writing :Godsell has published the following books.“A History of the Conservative Party” was the first critical history of the British Conservatives ever published....

(2008), "The Peasants' Revolt and the Radical Tradition" in Legends of British History - P. J. P. Goldberg (2004), Medieval England 1250–1550: A Social History, ISBN 0-340-57745-2; Chapter 13 is devoted to the Peasants' Revolt.

- Christopher Hampton (1984), A Radical Reader: The Struggle for Change in England, 1381–1914

- John J. Robinson (1990), Born in Blood: The Lost Secrets of Freemasonry, ISBN 0-87131-602-1; Chapters 1–5 concern the Peasants' Revolt. It makes a (somewhat speculative) case for a Knights TemplarKnights TemplarThe Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon , commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders...

connection, tracing some revolt features (e.g., the names of leaders, especially Wat Tyler, the special targets of the destruction in London, etc.) to traditions surviving the suppression of that order and its destruction on the Continent a few generations earlier. - A contemporary chronicle, the final meeting of King Richard II and the leader of the Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler.

- "The Peasants' Revolt", Voices of the powerless – readings from original sources, BBCBBCThe British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

Radio programme, Thursday 25 July 2002, 9.02 am – 9.30 am. - Britannia: The History of the Peasants' Revolt by Jeff Hobbs with useful bibliography

- "Wat Tyler's Rebellion" from The Chronicles of Froissart

- "King Richard punishes the rebels in Kent" from The Chronicles of Froissart, edited by Steve Muhlberger, Nipissing University

- A Dream of John Ball; and, a King's Lesson by William Morris (Project GutenbergProject GutenbergProject Gutenberg is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, to "encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks". Founded in 1971 by Michael S. Hart, it is the oldest digital library. Most of the items in its collection are the full texts of public domain books...

etext) - "Conflagration: The Peasants' Revolt" by Melissa Snell

- Fire, Bed & Bone by Henrietta Branford is a children's book looking at the Peasants' Revolt from the viewpoint of one of the participants' dogs.