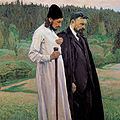

Pavel Florensky

Encyclopedia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

n Orthodox

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church or, alternatively, the Moscow Patriarchate The ROC is often said to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world; including all the autocephalous churches under its umbrella, its adherents number over 150 million worldwide—about half of the 300 million...

theologian, philosopher, mathematician

Mathematician

A mathematician is a person whose primary area of study is the field of mathematics. Mathematicians are concerned with quantity, structure, space, and change....

, electrical engineer

Electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is a field of engineering that generally deals with the study and application of electricity, electronics and electromagnetism. The field first became an identifiable occupation in the late nineteenth century after commercialization of the electric telegraph and electrical...

, inventor and Neomartyr sometimes compared by his followers to Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance...

.

Early life

Pavel Aleksandrovich Florensky was born on January 21, 1882, into the family of a railroad engineer, (Aleksandr Florensky) in the town of YevlakhYevlakh

Yevlakh is a small city in Azerbaijan, 265 km west of capital Baku. It is surrounded by, but administratively separate from, the rayon of the same name...

in western Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan , officially the Republic of Azerbaijan is the largest country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Located at the crossroads of Western Asia and Eastern Europe, it is bounded by the Caspian Sea to the east, Russia to the north, Georgia to the northwest, Armenia to the west, and Iran to...

. His father came from a family of Russian Orthodox

Russian Orthodox Church

The Russian Orthodox Church or, alternatively, the Moscow Patriarchate The ROC is often said to be the largest of the Eastern Orthodox churches in the world; including all the autocephalous churches under its umbrella, its adherents number over 150 million worldwide—about half of the 300 million...

priests while his mother Olga (Salomia) Saparova (Saparyan, Sapharashvili) was of the Armenian nobility. His maternal grandmother Sofia Paatova (Paatashvili) was from Sighnaghi

Sighnaghi

Sighnaghi is a town in Georgia's easternmost region of Kakheti and the administrative center of the Sighnaghi District. It is one of the country's smallest towns with a population of 2,146 as of the 2002 census. Sighnaghi's economy is dominated by production of wine,traditional carpets and...

. Florensky "always searched for the roots of his Armenian family" and noted that they're coming from Karabakh

Karabakh

The Karabakh horse , also known as Karabakh, is a mountain-steppe racing and riding horse. It is named after the geographic region where the horse was originally developed, Karabakh in the Southern Caucasus, an area that is de jure part of Azerbaijan but the highland part of which is currently...

.

After graduating from Tbilisi

Tbilisi

Tbilisi is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Mt'k'vari River. The name is derived from an early Georgian form T'pilisi and it was officially known as Tiflis until 1936...

gymnasium

Gymnasium (school)

A gymnasium is a type of school providing secondary education in some parts of Europe, comparable to English grammar schools or sixth form colleges and U.S. college preparatory high schools. The word γυμνάσιον was used in Ancient Greece, meaning a locality for both physical and intellectual...

in 1899, Florensky entered the department of mathematics of Moscow State University

Moscow State University

Lomonosov Moscow State University , previously known as Lomonosov University or MSU , is the largest university in Russia. Founded in 1755, it also claims to be one of the oldest university in Russia and to have the tallest educational building in the world. Its current rector is Viktor Sadovnichiy...

and simultaneously studied philosophy. During this period the young Florensky, who had no religious upbringing, began taking an interest in studies beyond "the limitations of physical knowledge..." In 1904 he graduated from Moscow State University and declined a teaching position at the University: instead, he proceeded to study theology at the Ecclesiastical Academy in Sergiyev Posad

Sergiyev Posad

Sergiyev Posad is a city and the administrative center of Sergiyevo-Posadsky District of Moscow Oblast, Russia. It grew in the 15th century around one of the greatest of Russian monasteries, the Trinity Lavra established by St. Sergius of Radonezh. The town status was granted to it in 1742...

. During his theological study, he first came into contact with who would become his spiritual father and mentor, Elder Isidore

Elder Isidore

Elder Isidore was a Russian Orthodox monastic of Gethsemane Hermitage in Russia. Elder Isidore was born with the name John in Lyskov in an unknown year . While still in the womb, his mother was told to have visited St. Seraphim of Sarov, who called her from a crowd and bowed before her,...

on a visit to Gethsemane Hermitage. Together with fellow students Ern, Svenitsky and Brikhnichev he founded a society, the Christian Struggle Union (Союз Христиaнской Борьбы), with the revolutionary aim of rebuilding Russian society according to the principles of Vladimir Solovyov

Vladimir Solovyov (philosopher)

Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov was a Russian philosopher, poet, pamphleteer, literary critic, who played a significant role in the development of Russian philosophy and poetry at the end of the 19th century...

. Subsequently he was arrested for membership in this society in 1906: however, he later lost his interest in the Radical Christianity movement.

Intellectual interests

During his studies at the Ecclesiastical Academy, Florensky's interests included philosophyPhilosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, religion

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

, art

Art

Art is the product or process of deliberately arranging items in a way that influences and affects one or more of the senses, emotions, and intellect....

and folklore

Folklore

Folklore consists of legends, music, oral history, proverbs, jokes, popular beliefs, fairy tales and customs that are the traditions of a culture, subculture, or group. It is also the set of practices through which those expressive genres are shared. The study of folklore is sometimes called...

. He became a prominent member of the Russian Symbolism

Russian Symbolism

Russian symbolism was an intellectual and artistic movement predominant at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. It represented the Russian branch of the symbolist movement in European art, and was mostly known for its contributions to Russian poetry.-Russian symbolism in...

movement, started his friendship with Andrei Bely

Andrei Bely

Andrei Bely was the pseudonym of Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev , a Russian novelist, poet, theorist, and literary critic. His novel Petersburg was regarded by Vladimir Nabokov as one of the four greatest novels of the 20th century.-Biography:...

and published works in the magazines New Way (Новый Путь) and Libra (Весы). He also started his main philosophical work, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: an Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters. The complete book was published only in 1924 but most of it was finished at the time of his graduation from the academy in 1908.

According to Princeton University Press: "The book is a series of twelve letters to a "brother" or "friend," who may be understood symbolically as Christ

Christ

Christ is the English term for the Greek meaning "the anointed one". It is a translation of the Hebrew , usually transliterated into English as Messiah or Mashiach...

. Central to Florensky's work is an exploration of the various meanings of Christian love, which is viewed as a combination of philia (friendship) and agape (universal love). He describes the ancient Christian rites of the adelphopoiesis (brother making), joining male friends in chaste bonds of love. In addition, Florensky is one of the first thinkers in the twentieth century to develop the idea of the Divine Sophia

Sophiology

Sophiology is a philosophical concept regarding wisdom, as well as a theological concept regarding the wisdom of God...

, who has become one of the central concerns of feminist theologians."

After graduating from the academy, he taught philosophy there and lived at Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra

Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra

The Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius is the most important Russian monastery and the spiritual centre of the Russian Orthodox Church. The monastery is situated in the town of Sergiyev Posad, about 70 km to the north-east from Moscow by the road leading to Yaroslavl, and currently is home to...

until 1919. In 1911 he was ordained into the priesthood. In 1914 he wrote his dissertation, About Spiritual Truth. He published works on philosophy, theology, art theory, mathematics and electrodynamics. Between 1911 and 1917 he was the chief editor of the most authoritative Orthodox theological publication of that time, Bogoslovskiy Vestnik. He was also a spiritual teacher of the controversial Russian writer Vasily Rozanov

Vasily Rozanov

Vasily Vasilievich Rozanov was one of the most controversial Russian writers and philosophers of the pre-revolutionary epoch. His views have been termed the "religion of procreation", as he tried to reconcile Christian teachings with ideas of healthy sex and family life and not, as his adversary...

, urging him to reconcile with the Orthodox Church.

Period of Communist rule in Russia

After the October RevolutionOctober Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

he formulated his position as: "I am of a Philosophical and scientific world outlook developed by me, which contradicts the vulgar interpretation of communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

... but that does not prevent me to honestly work for the state service." After the closing down, by the Bolsheviks, of the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra (1918) and the Sergievo-Posad Church (1921), where he was the priest, he moved to Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

to work on the State Plan for Electrification of Russia (ГОЭЛРО) under the recommendation of Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

who strongly believed in Florensky's ability to help the government to electrify rural Russia. According to contemporaries, Florensky in his priest's cassock, working alongside other leaders of a Government department, was a remarkable sight.

In 1924, he published a large monograph

Monograph

A monograph is a work of writing upon a single subject, usually by a single author.It is often a scholarly essay or learned treatise, and may be released in the manner of a book or journal article. It is by definition a single document that forms a complete text in itself...

on dielectric

Dielectric

A dielectric is an electrical insulator that can be polarized by an applied electric field. When a dielectric is placed in an electric field, electric charges do not flow through the material, as in a conductor, but only slightly shift from their average equilibrium positions causing dielectric...

s, and his The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: an Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters. He worked simultaneously as the Scientific Secretary of the Historical Commission on Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra and published his works on ancient Russian art. He was rumoured to be the main organizer of the plot to save the relic

Relic

In religion, a relic is a part of the body of a saint or a venerated person, or else another type of ancient religious object, carefully preserved for purposes of veneration or as a tangible memorial...

s of St. Sergii Radonezhsky whose destruction had been ordered by the government.

In the second half of the 1920s, he mostly worked on physics and electrodynamics, publishing his main hard science work Imaginary numbers in Geometry («Мнимости в геометрии. Расширение области двухмерных образов геометрии») devoted to the geometrical interpretation of Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

's theory of relativity

Theory of relativity

The theory of relativity, or simply relativity, encompasses two theories of Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity. However, the word relativity is sometimes used in reference to Galilean invariance....

. Among other things, he proclaimed that the geometry of imaginary numbers predicted by the theory of relativity for a body moving faster than light is the geometry of the kingdom of God.

1928-1937: Exile, imprisonment, death

In 1928, Florensky was exiled to Nizhny NovgorodNizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod , colloquially shortened to Nizhny, is, with the population of 1,250,615, the fifth largest city in Russia, ranking after Moscow, St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk, and Yekaterinburg...

. After the intercession of Ekaterina Peshkova

Ekaterina Peshkova

Yekaterina Pavlovna Peshkova née Volzhina was a Soviet human rights activist and humanitarian, first wife of Maxim Gorky.Before the October Revolution she took an active part in the work of the Committee for Assistance to Russian Political Prisoners under the leadership of Vera Figner...

(wife of Maxim Gorky

Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov , primarily known as Maxim Gorky , was a Russian and Soviet author, a founder of the Socialist Realism literary method and a political activist.-Early years:...

), Florensky was allowed to return to Moscow. In 1933 he was arrested again and sentenced to ten years in the Labor Camps

Gulag

The Gulag was the government agency that administered the main Soviet forced labor camp systems. While the camps housed a wide range of convicts, from petty criminals to political prisoners, large numbers were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas and other instruments of...

by the infamous Article 58

Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code)

Article 58 of the Russian SFSR Penal Code was put in force on 25 February 1927 to arrest those suspected of counter-revolutionary activities. It was revised several times...

of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

's criminal code (clauses ten and eleven: "agitation against the Soviet system" and "publishing agitation materials against the Soviet system"). The published agitation materials were the monograph about the theory of relativity.

He served at the Baikal Amur Mainline camp, until 1934 when he was moved to Solovki

Solovki

The Solovki prison camp was located on the Solovetsky Islands, in the White Sea). It was the "mother of the GULAG" according to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn...

, there he conducted research into producing iodine

Iodine

Iodine is a chemical element with the symbol I and atomic number 53. The name is pronounced , , or . The name is from the , meaning violet or purple, due to the color of elemental iodine vapor....

and agar

Agar

Agar or agar-agar is a gelatinous substance derived from a polysaccharide that accumulates in the cell walls of agarophyte red algae. Throughout history into modern times, agar has been chiefly used as an ingredient in desserts throughout Asia and also as a solid substrate to contain culture medium...

out of the local seaweed

Seaweed

Seaweed is a loose, colloquial term encompassing macroscopic, multicellular, benthic marine algae. The term includes some members of the red, brown and green algae...

. In 1937 he was transferred to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

(then known as Leningrad

Leningrad

Leningrad is the former name of Saint Petersburg, Russia.Leningrad may also refer to:- Places :* Leningrad Oblast, a federal subject of Russia, around Saint Petersburg* Leningrad, Tajikistan, capital of Muminobod district in Khatlon Province...

) where he was sentenced by an extrajudicial

Extrajudicial punishment

Extrajudicial punishment is punishment by the state or some other official authority without the permission of a court or legal authority. The existence of extrajudicial punishment is considered proof that some governments will break their own legal code if deemed necessary.-Nature:Extrajudicial...

NKVD troika

NKVD troika

NKVD troika or Troika, in Soviet Union history, were commissions of three persons who convicted people without trial. These commissions were employed as an instrument of extrajudicial punishment introduced to circumvent the legal system with a means for quick execution or imprisonment...

to execution. According to a legend he was sentenced for the refusal to disclose the location of the head of St. Sergii Radonezhsky that the communists wanted to destroy. The Saint's head was indeed saved and in 1946, the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra was opened again. The relics of St. Sergii became fashionable once more. The Saint's relics were returned to Lavra by Pavel Golubtsov, later known as archbishop Sergiy.

Official Soviet information stated that Florensky died December 8, 1943 somewhere in Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

, but a study of the NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

archives after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

have shown that information to be false. Florensky was shot immediately after the NKVD troika

NKVD troika

NKVD troika or Troika, in Soviet Union history, were commissions of three persons who convicted people without trial. These commissions were employed as an instrument of extrajudicial punishment introduced to circumvent the legal system with a means for quick execution or imprisonment...

session in December 1937. Most probably he was executed at the Rzhevsky Artillery Range, near Toksovo

Toksovo

Toksovo is an urban locality in Vsevolozhsky District of Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located to the north of St. Petersburg on the Karelian Isthmus. It is served by two neighboring stations of the Saint Petersburg-Kuznechnoye railroad: Toksovo and Kavgolovo...

, which is located about twenty kilometers northeast of Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

and was buried in a secret grave in Koirangakangas near Toksovo together with 30,000 others who were executed by NKVD at the same time.

See also

- Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov

- Vladimir N. BeneshevichVladimir N. BeneshevichVladimir Nicolayevich Beneshevich was a scholar of Byzantine history and canon law, and a philologer and paleographer of the manuscripts in that sphere....

- Sergei BulgakovSergei BulgakovFr. Sergei Nikolaevich Bulgakov was a Russian Orthodox Christian theologian, philosopher and economist. Until 1922 he worked in Russia; afterwards in Paris.-Early life:...

- Theophilus of AntiochTheophilus of AntiochTheophilus, Patriarch of Antioch, succeeded Eros c. 169, and was succeeded by Maximus I c.183, according to Henry Fynes Clinton, but these dates are only approximations...

- SophiologySophiologySophiology is a philosophical concept regarding wisdom, as well as a theological concept regarding the wisdom of God...

- ImiaslavieImiaslavieImiaslavie or Imiabozhie , also spelled imyaslavie and imyabozhie, and also referred to as onomatodoxy, is a dogmatic movement which was condemned by the Russian Orthodox Church, but that is still promoted by some affiliated with Gregory Lourie of the "Russian Orthodox Autonomous Church" , and by...

- Andrei N. Kolmogorov

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)USSR Anti-Religious Campaign (1928–1941)The USSR anti-religious campaign of 1928–1941 was a new phase of anti-religious persecution in the Soviet Union The campaign began in 1929, with the drafting of new legislation that severely prohibited religious activities and called for a heightened attack on religion in order to further...