Patrick Hastings

Encyclopedia

Sir Patrick Gardiner Hastings KC

(17 March 1880 – 26 February 1952) was a British barrister

and politician noted for his long and highly successful career as a barrister and his short stint as Attorney General

. He was educated at Charterhouse School

until 1896, when his family moved to continental Europe

. There he learnt to shoot and ride horses, allowing him to join the Suffolk Imperial Yeomanry

after the outbreak of the Second Boer War

. After demobilisation he worked briefly as an apprentice to an engineer in Wales before moving to London to become a barrister. Hastings joined the Middle Temple

as a student on 4 November 1901, and after two years of saving money for the call to the Bar

he finally qualified as a barrister on 15 June 1904.

Hastings first rose to prominence as a result of the Case of the Hooded Man

in 1912, and became noted for his skill at cross-examination

s. After his success in Gruban v Booth

in 1917, his practice steadily grew, and in 1919 he became a King's Counsel (KC). Following various successes as a KC in cases such as Sievier v Wootton and Russell v Russell, his practice was put on hold in 1922 when he was returned as the Labour

Member of Parliament for Wallsend

. Hastings was appointed Attorney General for England and Wales

in 1924, by the first Labour government, and knighted. His authorisation of the prosecution of J. R. Campbell

in what became known as the Campbell Case

, however, led to the fall of the government after less than a year in power.

Following his resignation in 1926 to allow Margaret Bondfield

to take a seat in Parliament, Hastings returned to his work as a barrister, and was even more successful than before his entry into the House of Commons. His cases included the Savidge Inquiry and the Royal Mail Case

, and before his full retirement in 1948 he was one of the highest paid barristers at the English Bar. As well as his legal work, Hastings also tried his hand at writing plays. Although these had a mixed reception, The River was made into a silent film in 1927 named The Notorious Lady. Following strokes in 1948 and 1949, his activities became heavily restricted, and he died at home on 26 February 1952.

Hastings was born on 17 March 1880 in London to Alfred Gardiner Hastings and Kate Comyns Carr, a painter and the sister of J. Comyns Carr

Hastings was born on 17 March 1880 in London to Alfred Gardiner Hastings and Kate Comyns Carr, a painter and the sister of J. Comyns Carr

. Having been born on Saint Patrick's Day

Hastings was named after the saint. His father was a solicitor with "somewhat seedy clients", and the family were repeatedly bankrupted. Despite financial difficulties ,there was enough money in the family to send Hastings to a private preparatory school

in 1890 and to Charterhouse School

in 1894. Hastings disliked school, saying "I hated the bell which drove us up in the morning, I hated the masters; above all I hated the work, which never interested me in the slightest degree". He was bullied at both the preparatory school and at Charterhouse, and did not excel at either sports or his studies.

By 1896 the family had hit another period of financial trouble, and Hastings left Charterhouse to move to continental Europe with his mother and older brother Archie until there was enough money for the family to return to London. The family initially moved to Ajaccio

in Corsica

, where they bought several old guns and taught Hastings and his brother how to shoot. After six months in Ajaccio the family moved again, this time to the Ardennes

, where they also learnt how to fish and ride horses.

While they were in the Ardennes, Hastings and his brother were arrested and briefly held for murder. While attending a fête in a nearby village Archie got into a disagreement with the local priest, who accused him of insulting the French church after misunderstanding one of his comments. The brothers returned to see the priest the next day to demand an apology, and after receiving it, they began to return home. On the way there they were stopped by two gendarmes

who arrested them for murder, informing them that the priest had been found dead ten minutes after they left his house. As the gendarmes prepared to take the Hastings to the police station, two more officers turned up with a villager in handcuffs. It transpired that the priest had been having an affair with the villager's sister, and after waiting for the Hastings to leave he had entered the priest's house and killed him with a brick. The Hastings were quickly released.

Soon after this incident, the family moved from the Ardennes to Brussels

after a message from their father that the financial problems had ended. When they reached Brussels they found that the situation was actually worse than previously, and the family moved between cheap hotels, each one worse than the one before. Desperate for a job, Hastings accepted the offer of an apprenticeship with an English engineer who claimed to have made a machine to extract gold in North Wales. After about a year and a half of work they discovered that there was no gold to be found in that part of Wales, and Hastings was informed that his services would no longer be needed.

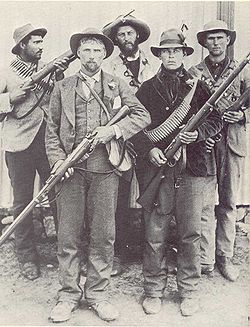

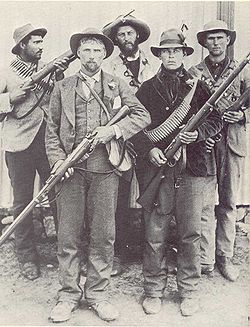

Hastings left the failed mining operation in 1899, and travelled to London. Just after he arrived, the Second Boer War

Hastings left the failed mining operation in 1899, and travelled to London. Just after he arrived, the Second Boer War

broke out, and the British government called for volunteers to join an expeditionary force. The only qualifications required were that the recruit could ride and shoot, and Hastings immediately applied to join the Suffolk Imperial Yeomanry

. He was accepted, and after two weeks of training the regiment were given horses and boarded the S.S. Goth Castle to South Africa. The ship reached Cape Town

after three weeks, and the regiment disembarked. Their horses were considered too weak to be ridden, and so they were instead discharged and either put down or given to other soldiers. Hastings did not enjoy his time in the army; the weather was poor, the orders given were confusing and they were provided with minimal equipment.

Hastings was made a scout, a duty he thoroughly enjoyed; it meant that he got to the targeted farms first, and had time to steal chickens and other food before the Royal Military Police

arrived (as looting was a criminal offence). Hastings was not a model soldier; as well as looting, he estimated that by the time he left the army he had "been charged and tried upon almost every offence known to military law". After two years of fighting, the Treaty of Vereeniging

was signed in 1902, bringing an end to the Second Boer War, and his regiment was returned to London and demobilised

.

By the time Hastings returned, he had decided to become a barrister

. There were various problems with this aim: in particular, he had no money, and the training for barristers was extremely expensive. Despite this, he refused to consider a change of career, and joined the Middle Temple

as a student on 4 November 1901. It is uncertain why he chose this particular Inn of Court (his uncle J. Comyns Carr

, his only connection with the Bar, was a member of the Inner Temple

), but the most likely explanation was that the Middle Temple was popular with Irish barristers, and Hastings was of Irish ancestry. The examinations required to become a barrister were not particularly difficult or expensive, but once a student passed all the exams he would be expected to pay the then-enormous sum of £

100 when he was called to the Bar – £100 in 1901 would be worth approximately £ as of – and Hastings was literally penniless.

As soon as he joined the Middle Temple, Hastings began saving money for his call to the Bar, starting with half a crown from the sale of his Queen's South Africa Medal

to a pawnbroker

. The rules and regulations of the Inns of Court meant that a student was not allowed to work as a "tradesperson" but there was no rule against working as a journalist, and his cousin Philip Carr, a drama critic for the Daily News

, got him a job writing a gossip column for the News for one pound a week. This job lasted about three months; both he and Carr were fired after Hastings wrote a piece for the paper that should have been done by Carr. Despite this, his new contacts within journalism allowed him to get temporary jobs writing play reviews for the Pall Mall Gazette

and the Ladies' Field. After two years of working eighteen-hour days he had saved £60 of the £100 needed to be called to the Bar, but had still not studied for the examinations as he could not afford to buy any law books. Over the next year his income decreased, as he was forced to study for the examinations rather than work for newspapers. By the end of May 1904 he had the £100 needed, and he was called to the bar on 15 June.

At the time, there was no organised way for a new barrister to find a pupil master

At the time, there was no organised way for a new barrister to find a pupil master

or set of chambers

, and in addition the barrister would be expected to pay the pupil master between 50 and 100 guineas

(equivalent to between £ and £ as of ). This was out of the question for Hastings; thanks to the cost of his call to the Bar

, he was so poor that his wig and robes had to be bought on credit

. Instead he wandered around Middle Temple and by chance ran into Frederick Corbet, the only practising barrister he knew. After Hastings explained his situation, Corbet offered him a place in his set of chambers, which Hastings immediately accepted. Although he now had a place in chambers, Hastings had no way of getting a pupillage

(Corbet only dealt with Privy Council

cases) and he instead decided to teach himself by watching cases at the Royal Courts of Justice

. Hastings was lucky: the first case he saw involved Rufus Isaacs

, Henry Duke

and Edward Carson

, three of the most distinguished English barristers of the early 20th century. For the next six weeks until the court vacation

, Hastings followed these three barristers from court to court "like a faithful hound".

At the start of the court vacation in August 1904, Hastings decided that it would be best to find a tenancy

At the start of the court vacation in August 1904, Hastings decided that it would be best to find a tenancy

in a more prestigious set of chambers; Corbet only dealt with two or three cases a year, and solicitor

s were unlikely to give briefs

to a barrister of whom they had never heard. The set of chambers below Corbet's was run by Charles Gill, a well-respected barrister. Hastings would be able to improve his career through an association with Gill, but Gill did not actually know Hastings and had no reason to offer him a place in his chambers. Hastings decided he would spend the court vacation writing a law book, and introduce himself to Gill by asking if he would mind having the book dedicated to him. Hastings wrote the book on the subject of the law relating to money-lending, something he knew very little about. He got around this by including large extracts from the judgements in cases related to money-lending, which increased the size of the book and reduced how much he would actually have to write.

Hastings finished the book just before the court vacation ended, and presented the draft to Gill immediately. Gill did not offer Hastings a place in his chambers but instead gave him a copy of a brief "to see if he could make a note on it that would be any use to [Gill]". He spent hours writing notes and "did everything to the brief except set it to music", before returning it to a pleased Gill, who let him take away another brief. Over the next two years Gill allowed him to work on nearly every case he appeared in. Eventually he was noticed by solicitors, who left briefs for him rather than for Gill. By the end of his first year as a barrister, he had earned 60 guineas, and by the end of his second year he had earned £200 (equivalent to approximately £ and £ respectively as of ).

On 1 June 1906, Hastings married Mary Grundy, the daughter of retired Lieutenant Colonel

F. L. Grundy, at All Saints' Church, Kensington

. They had met through his uncle J. Comyns Carr's family, who had brought Hastings to dinner at the Grundys' house. After several meetings Hastings proposed, but the wedding was put off for a long time due to his lack of money. In January 1906, Hastings became the temporary secretary of John Simon

, who had just become a Member of Parliament, and when he left the position Simon gave him a cheque for £50. Hastings and his finance had "never had so much money before", and on the strength of this they decided to get married. His marriage changed his outlook on life: he now realised that to provide for his wife he would need to work a lot harder at getting cases. To do that he would need to join a well-respected set of chambers; although Gill was giving him briefs he was still in Corbet's chambers, which saw little business.

Hastings approached Gill and asked him for a place in his chambers. Gill's chambers were full but he did suggest a well-respected barrister named F. E. Smith

, and Hastings went to see him with a letter of recommendation from Gill. Smith was out and Hastings instead spoke to his clerk

; the two did not get on, and Hastings left without securing a place. Hastings later described this as "the most fortunate moment of my whole career". Directly below Smith's chambers were those of Horace Avory

, one of the most noted barristers of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As he prepared to return home, Hastings was informed that Chartres Biron (one of the barristers who occupied Avory's chambers) had been appointed a Metropolitan Magistrate, which freed up a space in the chambers. He immediately went to Avory's clerk and got him to introduce Hastings to Avory. Avory initially refused to give Hastings a place in the chambers, but after Hastings lost his temper and exclaimed that "if he didn't want me to help him it would leave me more time to myself", Avory laughed and changed his mind.

Although this was a good start, Hastings was not a particularly well-known barrister, and cases were few and far between. To get around the lack of funds Hastings accepted a pupil

, and for the next year Hastings lived almost exclusively off the fees that the pupil paid him. To maintain the appearance of an active and busy chamber Hastings had his clerk borrow papers from other barristers and give them to the pupil to work on, claiming that they were cases of Hastings.

His first major case was "The Case of the Hooded Man". On 9 October 1912, the driver of a horse-drawn carriage noticed a crouching man near the front door of the house of Countess Flora Sztaray in Eastbourne

His first major case was "The Case of the Hooded Man". On 9 October 1912, the driver of a horse-drawn carriage noticed a crouching man near the front door of the house of Countess Flora Sztaray in Eastbourne

. Sztaray was known to possess large amounts of valuable jewellery and to be married to a rich Hungarian nobleman, and assuming that the crouching man was a burglar the driver immediately called the police. Inspector

Arthur Walls was sent to investigate, and ordered the man to come down. The man fired two shots, the first of which struck and killed Walls.

A few days after the murder, a former medical student named Edgar Power contacted the police, showing them a letter that he claimed had been written by the murderer. It read "If you would save my life come here at once to 4 Tideswell Road. Ask for Seymour. Bring some cash with you. Very Urgent." Power told the police that the letter had been written by a friend of his called John Williams, who he claimed had visited Sztaray's house to burgle it before killing the policeman and fleeing. Williams then met with his girlfriend Florence Seymour and explained what had happened. The two decided to bury the gun on the beach and send a letter to Williams' brother asking for money to return to London, which was then given to Powers.

Powers helped the police perform a sting operation

, telling Seymour that the police knew what had happened and that the only way to save Williams was to dig up the gun and move it to somewhere more safe. When Seymour and Powers went to do this, several policemen (who had been lying in wait) immediately arrested her and Powers (who was released a few hours later). Seymour was in a poor condition both physically and mentally, and after a few hours she wrote and signed a statement which incriminated Williams. Powers again helped the police, convincing Williams to meet him at Moorgate station

, where Williams was arrested by the police and charged with the murder of Arthur Walls. Williams maintained that he was innocent of the murder and burglary.

Williams' case came to trial on 12 December 1912 at Lewes Assizes

, with Hastings for the defence. Despite a strong argument and little direct evidence against William, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. The case generated large amounts of publicity, as well as an appeal hearing at which Hastings demonstrated his legal skills. The case established him as an excellent barrister, particularly when it came to cross-examination

. He was commended by both the initial judge, Arthur Channell, and the presiding judge hearing the appeal, Lord Alverstone

, for his skill in his defence of Williams. The advertisement this case gave of his skills allowed him to move some of his practice from the county court

s to the High Court of Justice

, where his work slowly increased in value and size.

The case made his name well-known and helped bring him work, but he still mainly worked on cases in the county courts. These did not pay particularly well, and to get around this lack of money his clerk had him take on six new pupils at once. The short length of county court cases and the number of cases Hastings got meant that he dealt with up to six cases in a single day, running from court to court with his pupils in a "Mafeking

procession" which he later described as "the forerunners of the modern Panzer division

".

, a noted Liberal

Member of Parliament who was chairman of the Yorkshire Iron and Coal Company and had led the government inquiry into the Marconi scandal

. When Gruban contacted Booth, Booth told him that he could do "more for [your] company than any man in England", claiming that David Lloyd George

(at the time Minister of Munitions

) and many other important government officials were close friends. With £3,500 borrowed from his brother-in-law, Booth immediately invested in Gruban's company.

Booth worked his way into the company with a string of false claims about his influence, and finally became chairman of the Board of Directors

by claiming that it was the only way to avoid Gruban being interned

due to his German origin. As soon as this happened, he cut Gruban out of the company, leaving him destitute, and eventually arranged for him to be interned. Gruban successfully appealed against the internment, and brought Booth to court.

The case of Gruban v Booth opened on 7 May 1917 in the King's Bench Division of the High Court of Justice

in front of Mr Justice Coleridge

. Patrick Hastings and Hubert Wallington represented Gruban, while Booth was represented by Rigby Swift

KC and Douglas Hogg

. The trial attracted such public interest that on the final day the barristers found it physically difficult to get through the crowds surrounding the Law Courts. While both Rigby Smith and Douglas Hogg were highly respected barristers, Booth's cross-examination

by Hastings was so skilfully done that the jury took only ten minutes to find that he had been fraudulent; they awarded Gruban £4,750 (about £ as of ).

1919 he applied to become a King's Counsel (KC). Becoming a KC was a risk; he would go from competing with other junior barristers to coming up against the finest minds in the profession. Despite this he decided to take the risk, and he was accepted later that year.

. Bersey was a senior officer of the Women's Royal Air Force

(WRAF), and along with several other officers he had been accused of conspiring to have the WRAF Commandant, Violet Douglas-Pennant

, removed from office to cover up "rife immorality" going on at WRAF camps. Lord Stanhope

formed a House of Lords

Select Committee to investigate these claims, and it began sitting on 14 October 1918.

Hastings took the lead in cross-examining Douglas-Pennant. She accused Bersey and others of promoting this "rife immorality" and not having the best interests of the WRAF

at heart. When cross examined, however, she was unable to provide any evidence of this "rife immorality" or any kind of a conspiracy, saying that she could not find any specific instance of "immorality" at the camps she visited and that it was "always rumour". After three weeks the committee dismissed all witnesses. The final report was produced in December 1919, and found that Douglas-Pennant had been completely unable to substantiate her claims and was deserving "of the gravest censure". As a result Douglas-Pennant was never again employed by the government.

During his time at the Bar, Hastings was involved in a variety of libel cases and in a divorce case which significantly changed the law relating to the admission of evidence from spouses regarding the legitimacy or illegitimacy of a child. His first significant libel case was Siever v Wootton. Robert Sievier was a well-known horse racing journalist and owner with a reputation for brushes with the law and underhanded dealings, having previously been tried for blackmail and acquitted on a technicality. In 1913 he accused Richard Wootton, a noted trainer of racehorses, of ordering his jockeys to withdraw from races if he had bet on another horse so as to allow him to make large amounts of money. Wootton sued him for libel and won, but was granted only a symbolic farthing in damages because the jury thought that Sievier had not intended to cause harm. As a result of this pyrrhic victory

During his time at the Bar, Hastings was involved in a variety of libel cases and in a divorce case which significantly changed the law relating to the admission of evidence from spouses regarding the legitimacy or illegitimacy of a child. His first significant libel case was Siever v Wootton. Robert Sievier was a well-known horse racing journalist and owner with a reputation for brushes with the law and underhanded dealings, having previously been tried for blackmail and acquitted on a technicality. In 1913 he accused Richard Wootton, a noted trainer of racehorses, of ordering his jockeys to withdraw from races if he had bet on another horse so as to allow him to make large amounts of money. Wootton sued him for libel and won, but was granted only a symbolic farthing in damages because the jury thought that Sievier had not intended to cause harm. As a result of this pyrrhic victory

, Wootton held a grudge against Sievier for many years.

As revenge, Wootton wrote a pamphlet titled Incidents in the Public Life of Robert Standish Sievier in which he claimed that Sievier had been expelled from the Victoria Racing Club

, twice been declared bankrupt, cheated a man of £600 in a game of billiards

and blackmailed another for £5,000. The pamphlet was released on the day of the Grand National

and distributed widely through the crowds, and in response Sievier sued Wootton for libel. Sievier appeared without a lawyer, while Wotton was represented by Sir Edward Carson KC, Hastings, and E. H. Spence. After the second day of the trial, Carson was called away to Ireland on political business, and Hastings was forced to act as the primary counsel for Wootton. Hastings destroyed Sievier's reputation in cross-examination, and the jury decided in Wootton's favour.

In 1922, he became involved in Russell v Russell, which eventually went to the House of Lords

, who set a common law

rule that evidence about the legitimacy or illegitimacy of children born in marriage is inadmissible if it is given by either spouse. Mr Russell, later Lord Ampthill

, married Mrs Russell in 1918, with both spouses agreeing that they did not want to have children. In October 1921 Mrs Russell gave birth to a son, Geoffrey Russell

, and Mr Russell immediately filed for divorce and to have the child declared a bastard. He claimed that the child could not be his because he had not had sexual intercourse with his wife since August 1920.

Hastings represented Mrs Russell in the initial trial at the High Court and lost; the decision was appealed to the Court of Appeal

, where he again lost. The case was then sent to the House of Lords

, who by a majority of three to two (with Lord Birkenhead

giving the leading judgment) overturned the previous judgments and said that Mr Russell's evidence as to the legitimacy of his son was inadmissible. Hastings did not represent Mrs Russell in the House of Lords case, however, because by this point he was already Attorney General

.

to help improve social conditions for the poorer people of the United Kingdom. He was being prepared to be the Liberal candidate for Ilford

in the 1918 general election

but grew disheartened by the Liberal alliance with the Conservative Party

, and also by the divisions in the party; as a result, he gave up the candidacy.

Hastings eventually switched sides and joined the Labour Party

. His conversion, especially in the light of later events, was regarded by some as suspect: his entry in the Dictionary of Labour Biography reports speculation that Hastings foresaw that Labour may come to Government and had few senior lawyers to fill the Law Officer

posts. John Paton

, after speaking from the same Independent Labour Party

(ILP) platform as Hastings, came to the conclusion that Hastings gave political speeches using his skill as a lawyer to master a brief; on the train home, Hastings appeared not to have heard of the ILP.

After an interview with Sidney and Beatrice Webb

he became the Labour candidate for Wallsend

in December 1920. Beatrice Webb was later to write in her diaries that Hastings was "without any sincerely held public purpose" and "an unpleasant type of clever pleader and political arriviste, who jumped into the Labour Party just before the 1922 election, when it had become clear that the Labour Party was the alternative government and it had not a single lawyer of position attached to it". However Hastings was returned for Wallsend with a majority of 2,823 in the 1922 general election

.

After returning to London from Wallsend, he attended a full meeting of Labour MPs to decide who would become the Party Chairman. This effectively meant choosing the leader of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition, because Labour was the largest opposition party in the House of Commons. The two candidates were Ramsay MacDonald

and J. R. Clynes, and Hastings, who supported MacDonald, persuaded six new MPs to support him. MacDonald was elected by a margin of only five votes, and Hastings later regretted his support.

Hastings was indeed Labour's only experienced barrister in the House of Commons at that time, and immediately became a frontbencher

and the party's main spokesman on legal matters. He made his debut speech on 22 February 1923 against the Rent Restrictions Bill, an amendment to the Rent Act 1921. He attacked it as "a monstrous piece of legislation", and was repeatedly shouted down by Conservative MPs as a "traitor to his class". As a result of this and the slow workings of Parliament, Hastings quickly became frustrated by politics.

the Irish Free State

was set up as an independent British Dominion covering most of the island of Ireland

. After a brief civil war

between the pro-Free State forces and members of the Irish Republican Army

(IRA) who wanted any independent nation to cover the entire island, the status of the Irish Free State was confirmed, and the IRA was forced underground. The IRA had supporters in the United Kingdom, working openly as the Irish Self-Determination League

(ISDL), and the Free State government shared the names of these supporters with the British authorities, who kept a close eye on them. Between February and March the Free State government provided information on individuals that they said were part of widespread plots against the Irish Free State being prepared on British soil. On 11 March 1923 the police in Britain arrested IRA sympathisers living in Britain including Art O'Brien, the head of the ISDL. Sources disagree on numbers, giving either approximately eighty or approximately 100. The arrested men were placed on special trains and sent to Liverpool, where they were transferred to Dublin via a Royal Navy

destroyer. It later transpired that not only were many British citizens (Art O'Brien himself had been born in England), at least six had never even been to Ireland before.

The next day the arrests were publicly queried in the House of Commons, and a Labour backbencher Jack Jones started a debate on the subject in the afternoon. W. C. Bridgeman, the Home Secretary

, said that he had directly ordered the police to arrest the ISDL members under the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act 1920

, and that he had consulted the Attorney General

who considered it perfectly legal. Hastings immediately stood and protested, saying that the Act was "one of the most dreadful things that has been done in the history of our country" and that the internments and deportations were effectively illegal.

A few days later, the solicitors for O'Brien got in contact with Hastings. On 23 March 1923 he appeared in R v Secretary of State for Home Affairs ex parte O'Brien

[1923] 2 KB 361 at a Divisional Court

consisting of Mr Justice Avory

and Mr Justice Salter to apply for a writ of habeas corpus

for O'Brien as a test case to allow the release of the others. The initial hearing was ineffective because Hastings was unable to provide an affidavit from O'Brien, which was required for a writ of habeas corpus to be considered, but by the time the hearing was resumed on 10 April he had managed to obtain one. Hastings argued that because the Irish Free State was an independent nation the British laws governing it, such as the 1920 Act, were effectively repealed.

The court eventually declared that they could not issue a writ, because the Habeas Corpus Act 1862

prevented them from issuing a writ to any colony possessing a court which could also issue a writ. Since Ireland possessed such a court, the English Divisional Court could not act. Hastings attempted to argue that the writ could be issued against the Home Secretary but this also failed, since the Home Secretary did not actually possess O'Brien. Three days later, Hastings took the case to the Court of Appeal, who declared that the internment orders were invalid since the Restoration of Order Act was no longer applicable. The Government was forced to introduce a Bill to Parliament giving itself retrospective immunity for having exceeded its authority, and the whole incident was a political and legal triumph for the party and for Hastings personally.

suggested that tariff reform was the best way to solve Britain's economic difficulties. Unfortunately Bonar Law, his predecessor, had promised that there would be no tariff reforms introduced during the current Parliament. Baldwin felt that the only solution was for the government to resign, which they did, and to call a new general election. In the ensuing election

Baldwin's Conservatives

lost 88 seats, with the Labour Party gaining 47 and the Liberal Party gaining 41. This produced a hung parliament

, and Labour and the Liberals formed a coalition government with Labour as the main party. Hastings himself was re-elected without difficulty, increasing his majority.

With Ramsay Macdonald

as the new Prime Minister in the first Labour government, Hastings was appointed Attorney-General for England and Wales. This was not surprising - Labour had only two KCs in Parliament, and the other (Edward Hemmerde

) was "unsuitable for personal reasons". Hastings hesitated before accepting the appointment, despite the knighthood and appointment as head of the Bar that came with the post, and later said that "if I had known what the next year was to bring forward I should almost certainly have [declined]".

Hastings described his time as Attorney General as "my idea of hell" - he was the only Law Officer available, since the Solicitor General was not a Member of Parliament, and as a result had to answer all queries about points of law in Parliament. In addition, he had his normal duties of dealing with the legal problems of government departments, and said that the day was "one long rush between the law courts, government departments and the House of Commons". His working hours were regularly between 7am and 5am the following morning, and the policemen on duty at the House of Commons complained to him that he was working too long, since they were required to stay on duty as long as he was.

, a prosecution which eventually led to the downfall of the Labour government. On 30 June 1924, he was met by Archibald Bodkin

, the Director of Public Prosecutions

, who brought with him a copy of the communist newspaper Workers' Weekly. The newspaper contained an article which urged members of the military to refuse to shoot their "fellow workers" in a time of war. Hastings approved the prosecution of the newspaper's editor, J. R. Campbell

, for violating the Incitement to Mutiny Act 1797

.

On 6 August Campbell's house was raided, and he was arrested by the police. On the same day John Scurr

On 6 August Campbell's house was raided, and he was arrested by the police. On the same day John Scurr

, a Labour backbencher

, asked the Home Secretary why Campbell had been detained and on whose orders. Hastings himself read out a reply, which said that the Director of Public Prosecutions had complained that the article was inciting troops to mutiny. Another Labour backbencher, Jimmy Maxton

, rose and asked the Prime Minister "if he has read the article, and if he is aware that the article contains mainly a call to the troops not to allow themselves to be used in industrial disputes, and that that point of view is shared by a large number of Members sitting on these benches?" This statement lead to uproar, and the Speaker was forced to intervene and halt further discussions.

The next day Hastings called for both the Solicitor General, Sir Henry Slesser

, and Jimmy Maxton, to ask their opinion on the prosecution. Maxton knew Campbell, and revealed that he was only the temporary editor and had not written the article – the article had actually been copied from another newspaper. Along with Guy Stevenson, the Assistant Director of Public Prosecutions, Hastings then visited Ramsay MacDonald to explain the facts of the case. MacDonald blamed the Director of Public Prosecutions for starting the case, although Hastings intervened and admitted to Macdonald that it was entirely his fault. The Prime Minister said that he felt they should go through with the case now they had started, but Hastings suggested that a member of the Treasury Counsel appear at Bow Street Magistrates Court and withdraw the prosecution. MacDonald agreed, and the next morning Travers Humphreys

appeared for the Crown at the Magistrates Court and had Campbell discharged.

The reaction of the public and the press was that the case had been thrown out because of direct pressure from the government, and that this had happened behind closed doors. MacDonald was "furious", and the opinion of the Liberal and Conservative parties was that the government was attempting to pervert the course of justice. On 30 September Sir Kingsley Wood

, a Conservative MP, asked the Prime Minister in Parliament whether he had instructed the Director of Public Prosecutions to withdraw the case. MacDonald replied that "I was not consulted regarding either the institution or the subsequent withdrawal of these proceedings".

A Parliamentary debate and motion to censure the Labour government on this was set for 8 October, but before this MacDonald called Hastings into his office and suggested a way to solve the problem. Hastings would accept all the blame and resign as Attorney General, and in exchange MacDonald and the rest of the cabinet would speak for Hastings at the resulting by-election. Hastings refused the general suggestion, but planned to make a speech at the upcoming debate explaining his actions.

Immediately after the debate began the Prime Minister rose to speak, and said that he "sought to correct the impression [I] gave" that he knew nothing about the prosecution. This was followed by a motion of censure pushed forward by Robert Horne

, and after Horne had presented the motion Hastings rose to speak, and explained the facts of the case. His speech took over an hour, and was frequently interrupted by Conservative MPs. In his speech, Hastings took full responsibility for both the decision to prosecute and the subsequent decision to withdraw the prosecution, asking whether a censure was merited for correcting a mistake. His speech quieted the Conservatives and made it clear that a censure for the entire Parliament was going to be difficult for the Whips to enforce. The Liberal spokesman John Simon

stood to speak, however, and called for the appointment of a Select Committee to investigate the case. This was rejected by MacDonald, and MPs continued to speak for several more hours.

The Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin

privately wrote to MacDonald offering to withdraw the motion of censure in exchange for the government's support for the appointment of a Select Committee. MacDonald consulted with Jimmy Thomas

and Hastings (whose reply was simply "go to hell") and decided to reject the offer. Although the motion of censure failed, the motion to appoint a Select Committee passed the House over the opposition of the government, and the Labour government was forced out of office. Hastings was embittered by the disaster, and considered immediately quitting politics altogether, although he did not do so. His plight was depicted on the cover of Time Magazine, along with a quotation ("What have I done wrong?") from his speech.

, although with a reduced majority. Although Hastings remained on the Labour frontbench he never spoke in the House of Commons again, and attended less and less frequently. After suffering from kidney problems during 1925, he left Parliament (by accepting the nominal position of Steward of the Manor of Northstead

(a legal fiction office with the same effect as, but less well known than, the Stewardship of the Chiltern Hundreds

) on 29 June 1926; this enabled Margaret Bondfield

, who had lost her seat in the previous election, to return to Parliament in his place at the ensuing by-election. He never returned to politics.

, a noted professional explorer, in his libel action against London Express Newspapers, the owner of the Daily Express

. The Daily Express had published two articles saying that he was a liar, and had planned out a bogus robbery to advertise a device known as the Monomark. The case opened on 9 February 1928 in front of Lord Hewart, with Hastings and Norman Birkett representing Mitchell-Hedges and William Jowitt and J.B. Melville representing London Express Newspapers. Despite the skills of both Hastings and Birkett, who later became a much-lauded barrister in his own right, Mitchell-Hedges lost his case and had his reputation destroyed as a result.

In 1928, Hastings became involved in the Savidge Inquiry. Sir Leo Chiozza Money

In 1928, Hastings became involved in the Savidge Inquiry. Sir Leo Chiozza Money

was a noted journalist, economist and former Liberal MP. On 23 April 1928, he and Miss Irene Savidge were sitting in Hyde Park

in London when they were arrested by two plain-clothes police officers and taken to the nearest police station, where they were charged under the Parks Regulation Act 1872 with committing an indecent offence. The next morning, they were remanded for a week at Great Marlborough Street Police Court. At the next hearing a week later, the case was dismissed by the magistrate, who criticised the police for failing to contact a man seen running through the park to establish some kind of corroborative evidence, and failing to report at once to Scotland Yard

to avoid having to charge the defendants immediately.

After his release, Money immediately spoke to his official contacts, and the next morning the matter was raised in the House of Commons. It was suggested that the police evidence was perjured

, and as a result the Home Secretary William Joynson-Hicks

instructed Sir Archibald Bodkin, the Director of Public Prosecutions, to investigate the possibility of perjury. Bodkin had the Metropolitan Police Commissioner appoint Chief Inspector Collins, one of his most experienced CID

officers, to investigate the claims and interview Savidge.

The next day, two police officers (Inspector Collins and Sergeant Clarke) and one policewoman (Lilian Wyles

) called at Savidge's workplace and took her to Scotland Yard, where she was questioned. The events of that day were brought up two days later in the House of Commons, where it was alleged that Savidge had been given a "third degree" interview by Collins lasting for five hours. A public outcry followed, and the Home Secretary appointed a tribunal to investigate.

The tribunal (led by Sir John Eldon Bankes, a former Lord Justice of Appeal

) began sitting on 15 May 1928; Hastings, Henry Curtis-Bennett

and Walter Frampton represented Savidge, and Norman Birkett represented the police. When called as a witness, Savidge testified that she had not wanted to go to Scotland Yard and had been persuaded to do so by the presence of a female police officer, Miss Wyles. After they arrived at Scotland Yard, Collins told Wyles that he was going to send Savidge home, and Wyles could leave. After Wyles had left, Collins began interviewing Savidge, threatening that she and Money would "suffer severely" if she did not tell the truth. Savidge said that Collins' manner had become more and more familiar during the interview, and that at several points he and Sergeant Clarke had implied that they wanted her to have sexual intercourse with them. Savidge spent almost six hours in the witness box, and her testimony left Collins looking guilty in the eyes of the tribunal. Collins, Clarke and Wyles were all interviewed, along with the Metropolitan Police Commissioner and Archibald Bodkin himself.

The final report of the tribunal was released on 13 June 1928 and consisted of both a majority report and a minority one, since not all of the tribunal members agreed on the validity of Savidge's evidence. The majority report said that Savidge was not intimidated into answering questions, nor treated inappropriately, and that "we are unable therefore to accept Miss Savidge's statement. We are satisfied that the interrogation followed the lines indicated to [Collins] by the Director of Public Prosecutions and was not unduly extended". The minority report blamed the police, particularly Collins, for the method in which Savidge was interviewed. The inquiry resulted in three changes to police procedure, however: firstly, that anyone interrogated should be told beforehand about the possible consequences and purpose of the statement; secondly, that the statement should normally be taken at home; and thirdly, that in cases "involving matters intimately affecting [a woman's] morals" another woman should always be present for any interviews.

began producing enough diamonds to attract the attention of the syndicate, and in November 1925 a Mr Oppenheimer, representing the syndicate, entered into a contract with Mr Perez, the operator of the Guiana mines, to have 12000 carats (2.4 kg) worth of diamonds provided to the syndicate over a twelve month period.

A few months later, United Diamond Fields of British Guiana was incorporated as a limited company

. The company used Oppenheimer as a technical adviser, and immediately arranged to have its diamonds sold to the syndicate. The price was to be fixed for six months, with an auditor's certificate at the end of that time used to negotiate a new price. Oppenheimer was the only one with access to the accounting information, and the rest of the company had no way of checking that his figures were correct. In the same time frame, a new deposit of diamonds was discovered in South Africa, forcing the syndicate to acquire several million pounds worth of these new diamonds to prevent their control over the market being destroyed. This strained their finances and the new diamonds forced the price down.

To correct this, the syndicate were forced to reduce the flow of diamonds from British Guiana, which they did by getting Oppenheimer to reduce the price of Guianan diamonds to the point where the company output dropped from 2000 carat (0.4 kg) a month to less than 300 carat (0.06 kg) per month. Oppenheimer then claimed that the profits were only five percent, forcing the company to reduce the price yet again. As a result of this the company was forced into liquidation in September 1927.

A company board member, Victor Coen, was convinced that the company had been treated wrongly and insisted in bringing it before the courts. In May 1929, he convinced the rest of the board to issue a writ against the syndicate and Oppenheimer, alleging fraudulent conspiracy, and began instructing Hastings. Hastings worried that the case would become unmanageable, with the syndicate relying on over 4,000 documents for their defence, but luckily found a certificate showing that the company profits, rather than the five percent Oppenheimer had reported, were in fact seventeen percent.

The trial began before Mr Justice McCardie

on 4 March 1930, with Hastings for the company, and Stuart Bevan

and Norman Birkett for the syndicate. The first witness called was Coen himself, who Hastings later described as "the best witness without exception that I have ever seen in the witness-box". He was interviewed over seven days by Hastings, then Bevan and then Birkett. Eight days into the trial the matter of the certificate came up, and Oppenheimer was unable to provide an explanation. As a result the jury found against the syndicate - they were ordered to pay back all of the company's costs, and all of its losses.

. The director of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company

, Lord Kylsant

, had falsified a trading prospectus with the aid of the company accountant, John Morland, to make it look as if the company was profitable and to entice potential investors. At the same time, he had been falsifying accounting records by drawing money from the reserves and having it appear on the records as profit. Following an independent audit instigated by the Treasury

, Kylsant and John Morland, the company auditor, were arrested and charged with falsifying both the trading prospectus and the company records and accounts.

The trial began at the Old Bailey

on 20 July 1931 before Mr Justice Wright

, with Sir William Jowitt

, D. N. Pritt

and Eustace Fulton for the prosecution, Sir John Simon

, J. E. Singleton and Wilfred Lewis for Lord Kylsant, and Hastings, Stuart Bevan

, Frederick Tucker

and C. J. Conway for John Morland. Both defendants pleaded not guilty.

The main defence on the use of secret reserve accounting came with the help of Lord Plender. Plender was one of the most important and reliable accountants in Britain, and under cross-examination stated that it was routine for firms "of the very highest repute" to use secret reserves in calculating profit without declaring it. Hastings said that "if my client ... was guilty of a criminal offence, there is not a single accountant in the City of London or in the world who is not in the same position." Both Kylsant and Morland were acquitted of falsifying records on this account, but Kylsant was found guilty of "making, circulating or publishing a written statement which he knew to be false", namely the 1928 prospectus, and was sentenced to 12 months in prison.

, and at a three day trial in the Old Bailey where Hastings was described by Peter Cotes in his book about the case as "the star performer".

At the Old Bailey one of the principal crown witnesses was firearms expert Robert Churchill, who testified that the trigger of Mrs Barney's gun had a strong pull. When Hastings rose to cross-examine, he took up the gun, pointed it to the ceiling and repeatedly pulled the trigger over and over again. One crown witness had said that on another occasion she saw Elvira Barney firing the gun while holding it in her left hand; when he called his client Hastings had the gun placed in front of her. After a pause he shouted at her to pick up the gun and she spontaneously picked it up in her right hand. The Judge (Mr Justice Humphreys) described Hastings' final address as "certainly one of the finest speeches I have ever heard at the Bar" and Elvira Barney was found not guilty both of murder and manslaughter.

in several cases during the 1930s, having become friends with him while in Parliament. The first was a libel case against The Star

, who had written a comment on one of Mosley's speeches implying that he advocated an armed revolution to overthrow the British government. The case opened at the Royal Courts of Justice on 5 November 1934 in front of Lord Hewart

, with Hastings representing Mosley, and Norman Birkett The Star. Birkett argued that The Star article was nothing more than a summary of Mosley's speech, and that any comments implying the overthrow of the British government were found in the speech itself. Hastings countered that The Star was effectively accusing Mosley of high treason, and said that "there is really no defence to this action...I do ask for such damages as will mark [the jury's] sense of the injustice which has been done to Sir Oswald". The jury eventually decided that The Star had libelled Mosley, and awarded him £5,000 in damages (approximately £ as of ).

Several weeks later, Hastings represented Mosley and three other members of the British Union of Fascists

(BUF) in a criminal case after they were indicted for "causing a riotous assembly

" on 9 October 1934 at a BUF meeting. The trial opened at the Sussex Assizes on 18 December 1934 in front of Mr Justice Branson, with Hastings for the defence and John Flowers KC prosecuting. According to Mosley, Hastings told him that Flowers, a former cricketer, had a poor reputation at the bar, and that Mosley should not show him up too much. The prosecution claimed that after a BUF meeting, Mosley and the other defendants had marched around Worthing, threatening and assaulting civilians. Hastings argued that the defendants had been deliberately provoked by a crowd of civilians, and several witnesses testified that the crowd had been throwing tomatoes and threatening Mosley. The judge eventually directed the jury to return a verdict of "not guilty". Hastings and Mosley were less successful in another libel action, against the Secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen

who had accused him of instructing his blackshirts

to arm themselves. The defence, led by D. N. Pritt

KC, called several witnesses to a fight in Manchester between blackshirts and their opponents. Hastings, taking the view that the incident was too long in the past to be relevant, did not call any rebutting evidence. Although Mosley won the case, he was awarded only a farthing in damages, traditionally a way for the jury to indicate that the case should not have been brought.

, where it was accepted and performed in June 1925. The play starred Owen Nares

and initially went well, but foundered in the second act due to the plot requiring the most popular actors to be taken off stage - the character played by Nares, for example, broke his leg. Reviews compared the plot to something out of the Boy's Own Paper

. The play lasted only a month before being cancelled, but Hastings was able to sell the film rights for £2,000, and it was turned into a Hollywood film called The Notorious Lady starring Lewis Stone

and Barbara Bedford.

His next play was titled Scotch Mist, and was put on at St Martin's Theatre

on 26 January 1926 starring Tallulah Bankhead

and Godfrey Tearle

. After a reviewer named John Ervine wrote a review starting "this is the worst play I have ever seen", the performances bizarrely sold out for weeks later. The play was later called "scandalous and immoral" by the Bishop of London

, Arthur Winnington-Ingram

, and as a result sold out for many months. Emboldened by this success Hastings wrote The Moving Finger, which despite moderately good reviews was not popular, and was withdrawn as a result. In 1930 he wrote Slings and Arrows, which never made it to the West End

because when his family, who were familiar with the play, attended the shows, they read out the lines of the characters in bored and dreary voices just before the actors themselves spoke. As a result the play was reduced to chaos.

offering his services, and was eventually contacted by Kingsley Wood

, the Secretary of State for Air

, who offered him a commission in the Royal Air Force

as a squadron leader

in Administrative and Special Duties Branch, serving with Fighter Command

. His commission was dated 25 September 1939. He then started work at RAF Stanmore Park

, but found his work "very depressing" - most of the other officers were over thirty years younger than he was, and he suffered from continuous bad health while there. His one major contribution was to create a scheme allowing the purchase of small models of German aircraft, allowing the British forces on the ground an easy way to identify incoming planes and avoiding friendly fire

situations. Due to his ill-health he relinquished his commission on 7 December 1939.

In Spring 1940 he was elected Treasurer of the Middle Temple

. He participated in only a few cases following his war service. One was a high-profile case in November and December 1946 in which he was engaged by the Newark

Advertiser in defence of a libel action brought by Harold Laski

, who was seeking to clear his name from the newspaper's claim that he had called for socialism "even if it means violence". Cross-examining Laski, the following exchange occurred:

Laski's counsel later said that he hoped that Hastings would at least have said "Touché". Laski lost the case, unable to counter the questioning from Hastings which referred to his previous written works.However the stress of the case told on Hastings.

In 1948, Hastings published his autobiography, simply titled The Autobiography of Sir Patrick Hastings, and the following year published Cases in Court, a book giving his views on 21 of his most noted cases. The same year he published Famous and Infamous Cases, a book on noted trials through history, such as those at Nuremberg

. In early 1948, he suffered a small stroke which forced him to retire permanently from work as a barrister. On 11 November 1949, he and his wife travelled to Kenya, where their son Nicky had moved to start a new life after the end of the Second World War. While there, he suffered a second stroke due to the air pressure, and he never fully recovered. Hastings spent the next two years of his life living in a flat in London, before dying on 26 February 1952 of cerebral thrombosis.

, and Nicholas became a farmer in Kenya. One daughter, Barbara, married Nicolas Bentley

, a cartoonist.

(17 March 1880 – 26 February 1952) was a British barrister

and politician noted for his long and highly successful career as a barrister and his short stint as Attorney General

. He was educated at Charterhouse School

until 1896, when his family moved to continental Europe

. There he learnt to shoot and ride horses, allowing him to join the Suffolk Imperial Yeomanry

after the outbreak of the Second Boer War

. After demobilisation he worked briefly as an apprentice to an engineer in Wales before moving to London to become a barrister. Hastings joined the Middle Temple

as a student on 4 November 1901, and after two years of saving money for the call to the Bar

he finally qualified as a barrister on 15 June 1904.

Hastings first rose to prominence as a result of the Case of the Hooded Man

in 1912, and became noted for his skill at cross-examination

s. After his success in Gruban v Booth

in 1917, his practice steadily grew, and in 1919 he became a King's Counsel (KC). Following various successes as a KC in cases such as Sievier v Wootton and Russell v Russell, his practice was put on hold in 1922 when he was returned as the Labour

Member of Parliament for Wallsend

. Hastings was appointed Attorney General for England and Wales

in 1924, by the first Labour government, and knighted. His authorisation of the prosecution of J. R. Campbell

in what became known as the Campbell Case

, however, led to the fall of the government after less than a year in power.

Following his resignation in 1926 to allow Margaret Bondfield

to take a seat in Parliament, Hastings returned to his work as a barrister, and was even more successful than before his entry into the House of Commons. His cases included the Savidge Inquiry and the Royal Mail Case

, and before his full retirement in 1948 he was one of the highest paid barristers at the English Bar. As well as his legal work, Hastings also tried his hand at writing plays. Although these had a mixed reception, The River was made into a silent film in 1927 named The Notorious Lady. Following strokes in 1948 and 1949, his activities became heavily restricted, and he died at home on 26 February 1952.

Hastings was born on 17 March 1880 in London to Alfred Gardiner Hastings and Kate Comyns Carr, a painter and the sister of J. Comyns Carr

Hastings was born on 17 March 1880 in London to Alfred Gardiner Hastings and Kate Comyns Carr, a painter and the sister of J. Comyns Carr

. Having been born on Saint Patrick's Day

Hastings was named after the saint. His father was a solicitor with "somewhat seedy clients", and the family were repeatedly bankrupted. Despite financial difficulties ,there was enough money in the family to send Hastings to a private preparatory school

in 1890 and to Charterhouse School

in 1894. Hastings disliked school, saying "I hated the bell which drove us up in the morning, I hated the masters; above all I hated the work, which never interested me in the slightest degree". He was bullied at both the preparatory school and at Charterhouse, and did not excel at either sports or his studies.

By 1896 the family had hit another period of financial trouble, and Hastings left Charterhouse to move to continental Europe with his mother and older brother Archie until there was enough money for the family to return to London. The family initially moved to Ajaccio

in Corsica

, where they bought several old guns and taught Hastings and his brother how to shoot. After six months in Ajaccio the family moved again, this time to the Ardennes

, where they also learnt how to fish and ride horses.

While they were in the Ardennes, Hastings and his brother were arrested and briefly held for murder. While attending a fête in a nearby village Archie got into a disagreement with the local priest, who accused him of insulting the French church after misunderstanding one of his comments. The brothers returned to see the priest the next day to demand an apology, and after receiving it, they began to return home. On the way there they were stopped by two gendarmes

who arrested them for murder, informing them that the priest had been found dead ten minutes after they left his house. As the gendarmes prepared to take the Hastings to the police station, two more officers turned up with a villager in handcuffs. It transpired that the priest had been having an affair with the villager's sister, and after waiting for the Hastings to leave he had entered the priest's house and killed him with a brick. The Hastings were quickly released.

Soon after this incident, the family moved from the Ardennes to Brussels

after a message from their father that the financial problems had ended. When they reached Brussels they found that the situation was actually worse than previously, and the family moved between cheap hotels, each one worse than the one before. Desperate for a job, Hastings accepted the offer of an apprenticeship with an English engineer who claimed to have made a machine to extract gold in North Wales. After about a year and a half of work they discovered that there was no gold to be found in that part of Wales, and Hastings was informed that his services would no longer be needed.

Hastings left the failed mining operation in 1899, and travelled to London. Just after he arrived, the Second Boer War

Hastings left the failed mining operation in 1899, and travelled to London. Just after he arrived, the Second Boer War

broke out, and the British government called for volunteers to join an expeditionary force. The only qualifications required were that the recruit could ride and shoot, and Hastings immediately applied to join the Suffolk Imperial Yeomanry

. He was accepted, and after two weeks of training the regiment were given horses and boarded the S.S. Goth Castle to South Africa. The ship reached Cape Town

after three weeks, and the regiment disembarked. Their horses were considered too weak to be ridden, and so they were instead discharged and either put down or given to other soldiers. Hastings did not enjoy his time in the army; the weather was poor, the orders given were confusing and they were provided with minimal equipment.

Hastings was made a scout, a duty he thoroughly enjoyed; it meant that he got to the targeted farms first, and had time to steal chickens and other food before the Royal Military Police

arrived (as looting was a criminal offence). Hastings was not a model soldier; as well as looting, he estimated that by the time he left the army he had "been charged and tried upon almost every offence known to military law". After two years of fighting, the Treaty of Vereeniging

was signed in 1902, bringing an end to the Second Boer War, and his regiment was returned to London and demobilised

.

By the time Hastings returned, he had decided to become a barrister

. There were various problems with this aim: in particular, he had no money, and the training for barristers was extremely expensive. Despite this, he refused to consider a change of career, and joined the Middle Temple

as a student on 4 November 1901. It is uncertain why he chose this particular Inn of Court (his uncle J. Comyns Carr

, his only connection with the Bar, was a member of the Inner Temple

), but the most likely explanation was that the Middle Temple was popular with Irish barristers, and Hastings was of Irish ancestry. The examinations required to become a barrister were not particularly difficult or expensive, but once a student passed all the exams he would be expected to pay the then-enormous sum of £

100 when he was called to the Bar – £100 in 1901 would be worth approximately £ as of – and Hastings was literally penniless.

As soon as he joined the Middle Temple, Hastings began saving money for his call to the Bar, starting with half a crown from the sale of his Queen's South Africa Medal

to a pawnbroker

. The rules and regulations of the Inns of Court meant that a student was not allowed to work as a "tradesperson" but there was no rule against working as a journalist, and his cousin Philip Carr, a drama critic for the Daily News

, got him a job writing a gossip column for the News for one pound a week. This job lasted about three months; both he and Carr were fired after Hastings wrote a piece for the paper that should have been done by Carr. Despite this, his new contacts within journalism allowed him to get temporary jobs writing play reviews for the Pall Mall Gazette

and the Ladies' Field. After two years of working eighteen-hour days he had saved £60 of the £100 needed to be called to the Bar, but had still not studied for the examinations as he could not afford to buy any law books. Over the next year his income decreased, as he was forced to study for the examinations rather than work for newspapers. By the end of May 1904 he had the £100 needed, and he was called to the bar on 15 June.

At the time, there was no organised way for a new barrister to find a pupil master

At the time, there was no organised way for a new barrister to find a pupil master

or set of chambers

, and in addition the barrister would be expected to pay the pupil master between 50 and 100 guineas

(equivalent to between £ and £ as of ). This was out of the question for Hastings; thanks to the cost of his call to the Bar

, he was so poor that his wig and robes had to be bought on credit

. Instead he wandered around Middle Temple and by chance ran into Frederick Corbet, the only practising barrister he knew. After Hastings explained his situation, Corbet offered him a place in his set of chambers, which Hastings immediately accepted. Although he now had a place in chambers, Hastings had no way of getting a pupillage

(Corbet only dealt with Privy Council

cases) and he instead decided to teach himself by watching cases at the Royal Courts of Justice

. Hastings was lucky: the first case he saw involved Rufus Isaacs

, Henry Duke

and Edward Carson

, three of the most distinguished English barristers of the early 20th century. For the next six weeks until the court vacation

, Hastings followed these three barristers from court to court "like a faithful hound".

At the start of the court vacation in August 1904, Hastings decided that it would be best to find a tenancy

At the start of the court vacation in August 1904, Hastings decided that it would be best to find a tenancy

in a more prestigious set of chambers; Corbet only dealt with two or three cases a year, and solicitor

s were unlikely to give briefs

to a barrister of whom they had never heard. The set of chambers below Corbet's was run by Charles Gill, a well-respected barrister. Hastings would be able to improve his career through an association with Gill, but Gill did not actually know Hastings and had no reason to offer him a place in his chambers. Hastings decided he would spend the court vacation writing a law book, and introduce himself to Gill by asking if he would mind having the book dedicated to him. Hastings wrote the book on the subject of the law relating to money-lending, something he knew very little about. He got around this by including large extracts from the judgements in cases related to money-lending, which increased the size of the book and reduced how much he would actually have to write.

Hastings finished the book just before the court vacation ended, and presented the draft to Gill immediately. Gill did not offer Hastings a place in his chambers but instead gave him a copy of a brief "to see if he could make a note on it that would be any use to [Gill]". He spent hours writing notes and "did everything to the brief except set it to music", before returning it to a pleased Gill, who let him take away another brief. Over the next two years Gill allowed him to work on nearly every case he appeared in. Eventually he was noticed by solicitors, who left briefs for him rather than for Gill. By the end of his first year as a barrister, he had earned 60 guineas, and by the end of his second year he had earned £200 (equivalent to approximately £ and £ respectively as of ).

On 1 June 1906, Hastings married Mary Grundy, the daughter of retired Lieutenant Colonel

F. L. Grundy, at All Saints' Church, Kensington

. They had met through his uncle J. Comyns Carr's family, who had brought Hastings to dinner at the Grundys' house. After several meetings Hastings proposed, but the wedding was put off for a long time due to his lack of money. In January 1906, Hastings became the temporary secretary of John Simon

, who had just become a Member of Parliament, and when he left the position Simon gave him a cheque for £50. Hastings and his finance had "never had so much money before", and on the strength of this they decided to get married. His marriage changed his outlook on life: he now realised that to provide for his wife he would need to work a lot harder at getting cases. To do that he would need to join a well-respected set of chambers; although Gill was giving him briefs he was still in Corbet's chambers, which saw little business.

Hastings approached Gill and asked him for a place in his chambers. Gill's chambers were full but he did suggest a well-respected barrister named F. E. Smith

, and Hastings went to see him with a letter of recommendation from Gill. Smith was out and Hastings instead spoke to his clerk

; the two did not get on, and Hastings left without securing a place. Hastings later described this as "the most fortunate moment of my whole career". Directly below Smith's chambers were those of Horace Avory

, one of the most noted barristers of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As he prepared to return home, Hastings was informed that Chartres Biron (one of the barristers who occupied Avory's chambers) had been appointed a Metropolitan Magistrate, which freed up a space in the chambers. He immediately went to Avory's clerk and got him to introduce Hastings to Avory. Avory initially refused to give Hastings a place in the chambers, but after Hastings lost his temper and exclaimed that "if he didn't want me to help him it would leave me more time to myself", Avory laughed and changed his mind.

Although this was a good start, Hastings was not a particularly well-known barrister, and cases were few and far between. To get around the lack of funds Hastings accepted a pupil

, and for the next year Hastings lived almost exclusively off the fees that the pupil paid him. To maintain the appearance of an active and busy chamber Hastings had his clerk borrow papers from other barristers and give them to the pupil to work on, claiming that they were cases of Hastings.

His first major case was "The Case of the Hooded Man". On 9 October 1912, the driver of a horse-drawn carriage noticed a crouching man near the front door of the house of Countess Flora Sztaray in Eastbourne

His first major case was "The Case of the Hooded Man". On 9 October 1912, the driver of a horse-drawn carriage noticed a crouching man near the front door of the house of Countess Flora Sztaray in Eastbourne

. Sztaray was known to possess large amounts of valuable jewellery and to be married to a rich Hungarian nobleman, and assuming that the crouching man was a burglar the driver immediately called the police. Inspector

Arthur Walls was sent to investigate, and ordered the man to come down. The man fired two shots, the first of which struck and killed Walls.

A few days after the murder, a former medical student named Edgar Power contacted the police, showing them a letter that he claimed had been written by the murderer. It read "If you would save my life come here at once to 4 Tideswell Road. Ask for Seymour. Bring some cash with you. Very Urgent." Power told the police that the letter had been written by a friend of his called John Williams, who he claimed had visited Sztaray's house to burgle it before killing the policeman and fleeing. Williams then met with his girlfriend Florence Seymour and explained what had happened. The two decided to bury the gun on the beach and send a letter to Williams' brother asking for money to return to London, which was then given to Powers.

Powers helped the police perform a sting operation

, telling Seymour that the police knew what had happened and that the only way to save Williams was to dig up the gun and move it to somewhere more safe. When Seymour and Powers went to do this, several policemen (who had been lying in wait) immediately arrested her and Powers (who was released a few hours later). Seymour was in a poor condition both physically and mentally, and after a few hours she wrote and signed a statement which incriminated Williams. Powers again helped the police, convincing Williams to meet him at Moorgate station

, where Williams was arrested by the police and charged with the murder of Arthur Walls. Williams maintained that he was innocent of the murder and burglary.

Williams' case came to trial on 12 December 1912 at Lewes Assizes

, with Hastings for the defence. Despite a strong argument and little direct evidence against William, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. The case generated large amounts of publicity, as well as an appeal hearing at which Hastings demonstrated his legal skills. The case established him as an excellent barrister, particularly when it came to cross-examination

. He was commended by both the initial judge, Arthur Channell, and the presiding judge hearing the appeal, Lord Alverstone

, for his skill in his defence of Williams. The advertisement this case gave of his skills allowed him to move some of his practice from the county court

s to the High Court of Justice

, where his work slowly increased in value and size.

The case made his name well-known and helped bring him work, but he still mainly worked on cases in the county courts. These did not pay particularly well, and to get around this lack of money his clerk had him take on six new pupils at once. The short length of county court cases and the number of cases Hastings got meant that he dealt with up to six cases in a single day, running from court to court with his pupils in a "Mafeking

procession" which he later described as "the forerunners of the modern Panzer division

".

, a noted Liberal

Member of Parliament who was chairman of the Yorkshire Iron and Coal Company and had led the government inquiry into the Marconi scandal

. When Gruban contacted Booth, Booth told him that he could do "more for [your] company than any man in England", claiming that David Lloyd George

(at the time Minister of Munitions

) and many other important government officials were close friends. With £3,500 borrowed from his brother-in-law, Booth immediately invested in Gruban's company.

Booth worked his way into the company with a string of false claims about his influence, and finally became chairman of the Board of Directors

by claiming that it was the only way to avoid Gruban being interned

due to his German origin. As soon as this happened, he cut Gruban out of the company, leaving him destitute, and eventually arranged for him to be interned. Gruban successfully appealed against the internment, and brought Booth to court.

The case of Gruban v Booth opened on 7 May 1917 in the King's Bench Division of the High Court of Justice

in front of Mr Justice Coleridge

. Patrick Hastings and Hubert Wallington represented Gruban, while Booth was represented by Rigby Swift

KC and Douglas Hogg

. The trial attracted such public interest that on the final day the barristers found it physically difficult to get through the crowds surrounding the Law Courts. While both Rigby Smith and Douglas Hogg were highly respected barristers, Booth's cross-examination

by Hastings was so skilfully done that the jury took only ten minutes to find that he had been fraudulent; they awarded Gruban £4,750 (about £ as of ).

1919 he applied to become a King's Counsel (KC). Becoming a KC was a risk; he would go from competing with other junior barristers to coming up against the finest minds in the profession. Despite this he decided to take the risk, and he was accepted later that year.

. Bersey was a senior officer of the Women's Royal Air Force

(WRAF), and along with several other officers he had been accused of conspiring to have the WRAF Commandant, Violet Douglas-Pennant

, removed from office to cover up "rife immorality" going on at WRAF camps. Lord Stanhope

formed a House of Lords

Select Committee to investigate these claims, and it began sitting on 14 October 1918.

Hastings took the lead in cross-examining Douglas-Pennant. She accused Bersey and others of promoting this "rife immorality" and not having the best interests of the WRAF

at heart. When cross examined, however, she was unable to provide any evidence of this "rife immorality" or any kind of a conspiracy, saying that she could not find any specific instance of "immorality" at the camps she visited and that it was "always rumour". After three weeks the committee dismissed all witnesses. The final report was produced in December 1919, and found that Douglas-Pennant had been completely unable to substantiate her claims and was deserving "of the gravest censure". As a result Douglas-Pennant was never again employed by the government.