Ostracism

Encyclopedia

Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed in the Greek city-state of Athens, comprising the central city-state of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica, around 508 BC. Athens is one of the first known democracies. Other Greek cities set up democracies, and even though most followed an Athenian model,...

in which any citizen could be expelled

Exile

Exile means to be away from one's home , while either being explicitly refused permission to return and/or being threatened with imprisonment or death upon return...

from the city-state

City-state

A city-state is an independent or autonomous entity whose territory consists of a city which is not administered as a part of another local government.-Historical city-states:...

of Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the victim, ostracism was often used preemptively. It was used as a way of defusing major confrontations between rival politician

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

s (by removing one of them from the scene), neutralizing someone thought to be a threat to the state, or exiling a potential tyrant

Tyrant

A tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

. Crucially, ostracism had no relation to the processes of justice. There was no charge or defense, and the exile was not in fact a penalty; it was simply a command from the Athenian people that one of their number be gone for ten years.

The procedure is to be distinguished from the modern use of the term, which generally refers to informal modes of exclusion from a group through shunning

Shunning

Shunning can be the act of social rejection, or mental rejection. Social rejection is when a person or group deliberately avoids association with, and habitually keeps away from an individual or group. This can be a formal decision by a group, or a less formal group action which will spread to all...

.

Procedure

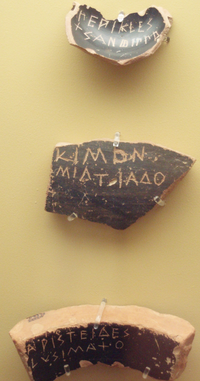

The name is derived from the ostrakaOstracon

An ostracon is a piece of pottery , usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In archaeology, ostraca may contain scratched-in words or other forms of writing which may give clues as to the time when the piece was in use...

, (singular ostrakon , ὄστρακον), referring to the pottery shard

Sherd

In archaeology, a sherd is commonly a historic or prehistoric fragment of pottery, although the term is occasionally used to refer to fragments of stone and glass vessels as well....

s that were used as voting tokens. Broken pottery, abundant and virtually free, served as a kind of scrap paper (in contrast to papyrus

Papyrus

Papyrus is a thick paper-like material produced from the pith of the papyrus plant, Cyperus papyrus, a wetland sedge that was once abundant in the Nile Delta of Egypt....

, which was imported from Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

as a high-quality writing surface, and was thus too costly to be disposable).

Each year the Athenians were asked in the assembly

Ecclesia (ancient Athens)

The ecclesia or ekklesia was the principal assembly of the democracy of ancient Athens during its "Golden Age" . It was the popular assembly, opened to all male citizens over the age of 30 with 2 years of military service by Solon in 594 BC meaning that all classes of citizens in Athens were able...

whether they wished to hold an ostracism. The question was put in the sixth of the ten months used for state business under the democracy (January or February in the modern Gregorian Calendar

Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar, also known as the Western calendar, or Christian calendar, is the internationally accepted civil calendar. It was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII, after whom the calendar was named, by a decree signed on 24 February 1582, a papal bull known by its opening words Inter...

). If they voted "yes", then an ostracism would be held two months later. In a section of the agora

Agora

The Agora was an open "place of assembly" in ancient Greek city-states. Early in Greek history , free-born male land-owners who were citizens would gather in the Agora for military duty or to hear statements of the ruling king or council. Later, the Agora also served as a marketplace where...

set off and suitably barriered, citizens scratched the name of a citizen they wished to expel on pottery shards, and deposited them in urn

Urn

An urn is a vase, ordinarily covered, that usually has a narrowed neck above a footed pedestal. "Knife urns" placed on pedestals flanking a dining-room sideboard were an English innovation for high-style dining rooms of the late 1760s...

s. The presiding officials counted the ostraka submitted and sorted the names into separate piles. The person whose pile contained the most ostraka would be banished, provided that an additional criterion was met, about which there are two contradictory reports:

- According to PhilochorusPhilochorusPhilochorus, of Athens, Greek historian during the 3rd century BC, , was a member of a priestly family. He was a seer and interpreter of signs, and a man of considerable influence....

, the "winner" of the ostracism must have obtained at least 6,000 votes. - According to Plutarchus, the ostracism was considered valid if the total number of votes cast was at least 6,000.

The person nominated had ten days to leave the city. If he attempted to return, the penalty was death

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

. Notably, the property of the man banished was not confiscated and there was no loss of status. After the ten years, he was allowed to return without stigma. It was possible for the assembly to recall an ostracised person ahead of time; before the Persian invasion of 479 BC

479 BC

Year 479 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Vibulanus and Rutilus...

, an amnesty was declared under which at least two ostracised leaders—Pericles

Pericles

Pericles was a prominent and influential statesman, orator, and general of Athens during the city's Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars...

' father Xanthippus and Aristides

Aristides

Aristides , 530 BC – 468 BC was an Athenian statesman, nicknamed "the Just".- Biography :Aristides was the son of Lysimachus, and a member of a family of moderate fortune. Of his early life, it is only told that he became a follower of the statesman Cleisthenes and sided with the aristocratic party...

'the Just'—are known to have returned. Similarly, Cimon, ostracised in 461 BC, was recalled during an emergency.

Distinction from other Athenian democratic processes

Ostracism was crucially different from Athenian lawAthenian law court (classical period)

The law courts in classical Athens were a fundamental organ of democratic governance. According to Aristotle, whoever controls the courts, controls the state....

at the time; there was no charge, and no defence could be mounted by the person expelled. The two stages of the procedure ran in the reverse order from that used under almost any trial system — here it is as if a jury are first asked "Do you want to find someone guilty?", and subsequently asked "Whom do you wish to accuse?". Equally out of place in a judicial framework is perhaps the institution's most peculiar feature: that it can take place at most once a year, and only for one person. In this it resembles the Greek pharmakos

Pharmakos

A Pharmakós in Ancient Greek religion was a kind of human scapegoat who was chosen and expelled from the community at times of disaster or at times of calendrical crisis, when purification was needed...

or scapegoat

Scapegoat

Scapegoating is the practice of singling out any party for unmerited negative treatment or blame. Scapegoating may be conducted by individuals against individuals , individuals against groups , groups against individuals , and groups against groups Scapegoating is the practice of singling out any...

— though in contrast, pharmakos generally ejected a lowly member of the community.

A further distinction between these two modes (and one not obvious from a modern perspective) is that ostracism was an automatic procedure that required no initiative from any individual, with the vote simply occurring on the wish of the electorate — a diffuse exercise of power. By contrast, an Athenian trial needed the initiative of a particular citizen-prosecutor. While prosecution often led to a counterattack (or was a counterattack itself), no such response was possible in the case of ostracism as responsibility lay with the polity as a whole. In contrast to a trial, ostracism generally reduced political tension rather than increased it.

Although ten years of exile would have been difficult for an Athenian to face, it was relatively mild in comparison to the kind of sentences inflicted by courts; when dealing with politicians held to be acting against the interests of the people, Athenian juries could inflict severe penalties such as death, unpayably large fines, confiscation of property, permanent exile and loss of citizens' rights through atimia

Atimia (loss of citizen rights)

Atimia was a form of disenfranchisement used under classical Athenian democracy. A person who was made atimos, literally without honour or value, was unable to carry out the political functions of a citizen...

. Further, the elite Athenians who suffered ostracism were rich or noble men who had connections or xenoi in the wider Greek world and who, unlike genuine exiles, were able to access their income in Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

from abroad. In Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

, following as he does the anti-democratic line common in elite sources, the fact that people might be recalled early appears to be another example of the inconsistency of majoritarianism

Majoritarianism

Majoritarianism is a traditional political philosophy or agenda which asserts that a majority of the population is entitled to a certain degree of primacy in society, and has the right to make decisions that affect the society...

that was characteristic of Athenian democracy. However, ten years of exile usually resolved whatever had prompted the expulsion. Ostracism was simply a pragmatic measure; the concept of serving out the full sentence did not apply as it was a preventative measure, not a punitive one.

One curious window on the practicalities of ostracism comes from the cache of 190 ostraka discovered dumped in a well next to the acropolis

Acropolis, Athens

Acropolis is a neighborhood of Athens, near the ancient monument of Acropolis, along the Dionysios Areopagitis, courier road. This neighborhood has a significant number of tourists all year round. It is the site of the Museum of Acropolis, opened in 2009....

. From the handwriting they appear to have been written by fourteen individuals and bear the name of Themistocles

Themistocles

Themistocles ; c. 524–459 BC, was an Athenian politician and a general. He was one of a new breed of politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy, along with his great rival Aristides...

, ostracised before 471 BC

471 BC

Year 471 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Sabinus and Barbatus...

and were evidently meant for distribution to voters. This was not necessarily evidence of electoral fraud

Electoral fraud

Electoral fraud is illegal interference with the process of an election. Acts of fraud affect vote counts to bring about an election result, whether by increasing the vote share of the favored candidate, depressing the vote share of the rival candidates or both...

(being no worse than modern voting instruction cards), but their being dumped in the well may suggest that their creators wished to hide them. If so, these ostraka provide an example of organized groups attempting to influence the outcome of ostracisms. The two-month gap between the first and second phases would have easily allowed for such a campaign.

There is another interpretation, however, according to which these ostraka were prepared beforehand by enterprising businessmen who offered to them for sale for persons who could not easily inscribe the desired names for themselves or who simply wished to save time.

The two-month gap is a key feature in the institution, much as in election

Election

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office. Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy operates since the 17th century. Elections may fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the...

s under modern liberal democracies

Liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also known as constitutional democracy, is a common form of representative democracy. According to the principles of liberal democracy, elections should be free and fair, and the political process should be competitive...

. It first prevented the candidate for expulsion being chosen out of immediate anger, although an Athenian general such as Cimon would have not wanted to lose a battle the week before such a second vote. Secondly, it opened up a period for discussion (or perhaps agitation), whether informally in daily talk or public speeches

Public speaking

Public speaking is the process of speaking to a group of people in a structured, deliberate manner intended to inform, influence, or entertain the listeners...

before the Athenian assembly or Athenian courts [#endnote_Oration *]. In this process a consensus, or rival consensuses, might emerge. Further, in that time of waiting, ordinary Athenian citizens must have felt a certain power over the greatest members of their city; conversely, the most prominent citizens had an incentive to worry how their social inferiors regarded them.

Period of operation

Ostracism was not in use throughout the whole period of Athenian democracy (circa 506–322 BC), but only occurred in the fifth century. The standard account, found in Aristotle'sAristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

Athenian Constitution 22.3, attributes the establishment to Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes was a noble Athenian of the Alcmaeonid family. He is credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508/7 BC...

, a pivotal reformer in the creation of the democracy. In that case ostracism would have been in place from around 506 BC. The first victim of the practice, however, was not expelled until 487 BC

487 BC

Year 487 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Sicinius and Aquillius...

— nearly twenty years later. Over the course of the next sixty years some twelve or more individuals followed him. The list may not be complete, but there is good reason to believe the Athenians did not feel the need to eject someone in this way every year. The list of known ostracisms runs as follows:

- 487 Hipparchos son of Charmos, a relative of the tyrantTyrantA tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

PeisistratosPeisistratos (Athens)Peisistratos was a tyrant of Athens from 546 to 527/8 BC. His legacy lies primarily in his institution of the Panathenaic Festival and the consequent first attempt at producing a definitive version for Homeric epics. Peisistratos' championing of the lower class of Athens, the Hyperakrioi, can be... - 486 MegaclesMegaclesMegacles was the name of several notable men of ancient Athens:1. Megacles was possibly a legendary Archon of Athens from 922 BC to 892 BC....

son of HippocratesHippocratesHippocrates of Cos or Hippokrates of Kos was an ancient Greek physician of the Age of Pericles , and is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine...

; Cleisthenes' nephew (possibly ostracised twice ) - 485 Kallixenos Nephew of CleisthenesCleisthenesCleisthenes was a noble Athenian of the Alcmaeonid family. He is credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508/7 BC...

and head of the Alcmaeonids at the time (not known for certain) - 484 XanthippusXanthippusXanthippus was a Greek mercenary general hired by the Carthaginians to aid in their war against the Romans during the First Punic War...

son of Ariphron; Pericles'PericlesPericles was a prominent and influential statesman, orator, and general of Athens during the city's Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars...

father - 482 AristidesAristidesAristides , 530 BC – 468 BC was an Athenian statesman, nicknamed "the Just".- Biography :Aristides was the son of Lysimachus, and a member of a family of moderate fortune. Of his early life, it is only told that he became a follower of the statesman Cleisthenes and sided with the aristocratic party...

son of Lysimachus - 471 ThemistoclesThemistoclesThemistocles ; c. 524–459 BC, was an Athenian politician and a general. He was one of a new breed of politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy, along with his great rival Aristides...

son of Neocles (last possible year) - 461 Cimon son of MiltiadesMiltiadesMiltiades or Miltiadis is a Greek name. Several historic persons have been called Miltiades .* Miltiades the Elder wealthy Athenian, and step-uncle of Miltiades the Younger...

- 460 Alcibiades son of Kleinias; grandfather of AlcibiadesAlcibiadesAlcibiades, son of Clinias, from the deme of Scambonidae , was a prominent Athenian statesman, orator, and general. He was the last famous member of his mother's aristocratic family, the Alcmaeonidae, which fell from prominence after the Peloponnesian War...

(possibly ostracised twice ) - 457 Menon son of Meneclides [less certain]

- 442 ThucydidesThucydides (politician)Thucydides was a prominent politician of ancient Athens and the leader for a number of years of the powerful conservative faction. While it is likely he is related to the later historian Thucydides son of Olorus, the details are uncertain; maternal grandfather and grandson fits the available...

son of Milesias - 440s Callias son of Didymos [less certain]

- 440s DamonDamon (ancient Greek musicologist)Damon, son of Damonides, was a Greek musicologist of the fifth century BC. He belonged to the Athenian deme of Oē . He is credited as teacher and advisor of Pericles.-Music:...

son of Damonides [less certain] - 416 HyperbolosHyperbolosHyperbolus was an Athenian politician active during the first half of the Peloponnesian war, coming to particular prominence after the death of Cleon....

son of Antiphanes (+/- 1 year)

Around twelve thousand political ostraka have been excavated in the Athenian agora and in the Kerameikos . The second victim, Cleisthenes' nephew Megacles, is named by 4647 of these, but for a second undated ostracism not listed above. The known ostracisms seem to fall into three distinct phases: the 480s BC, mid-century 461–443 BC and finally the years 417–415: this matches fairly well with the clustering of known expulsions, although Themistocles before 471 may count as an exception. This suggests that ostracism fell in and out of fashion.

The last known ostracism was that of Hyperbolos

Hyperbolos

Hyperbolus was an Athenian politician active during the first half of the Peloponnesian war, coming to particular prominence after the death of Cleon....

in circa 417 BC

417 BC

Year 417 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Tribunate of Tricipitinus, Lanatus, Crassus and Axilla...

. There is no sign of its use after the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

, when democracy was restored after the oligarchic coup of the Thirty

Thirty Tyrants

The Thirty Tyrants were a pro-Spartan oligarchy installed in Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Contemporary Athenians referred to them simply as "the oligarchy" or "the Thirty" ; the expression "Thirty Tyrants" is due to later historians...

had collapsed in 403 BC

403 BC

Year 403 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Tribunate of Mamercinus, Varus, Potitus, Iullus, Crassus and Fusus...

. However, while ostracism was not an active feature of the 4th-century version of democracy, it remained; the question was put to the assembly each year, but they did not wish to hold one.

Purpose of ostracism

Because ostracism was carried out by thousands of people over many decades of an evolving political situation and culture, it did not serve a single monumental purpose. Still, observations can be made about outcomes, as well as the initial purpose for which it was created.The first rash of people ostracised in the decade after the defeat of the first Persian invasion at Marathon

Marathon, Greece

Marathon is a town in Greece, the site of the battle of Marathon in 490 BC, in which the heavily outnumbered Athenian army defeated the Persians. The tumulus or burial mound for the 192 Athenian dead that was erected near the battlefield remains a feature of the coastal plain...

in 490 BC were all related or connected to the tyrant

Tyrant

A tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

Peisistratos

Peisistratos (Athens)

Peisistratos was a tyrant of Athens from 546 to 527/8 BC. His legacy lies primarily in his institution of the Panathenaic Festival and the consequent first attempt at producing a definitive version for Homeric epics. Peisistratos' championing of the lower class of Athens, the Hyperakrioi, can be...

, who had controlled Athens for 36 years up to 527 BC. After his son Hippias was deposed with Sparta

Sparta

Sparta or Lacedaemon, was a prominent city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the banks of the River Eurotas in Laconia, in south-eastern Peloponnese. It emerged as a political entity around the 10th century BC, when the invading Dorians subjugated the local, non-Dorian population. From c...

n help in 510 BC, the family sought refuge with the Persians, and nearly twenty years later Hippias landed with their invasion force at Marathon. Tyranny and Persian aggression were paired threats facing the new democratic regime at Athens, and ostracism was used against both.

Tyranny and democracy had arisen at Athens out of clashes between regional and factional groups organised around politicians, including Cleisthenes. As a reaction, in many of its features the democracy strove to reduce the role of factions as the focus of citizen loyalties. Ostracism, too, may have been intended to work in the same direction: by temporarily decapitating a faction, it could help to defuse confrontations that threatened the order of the State.

In later decades when the threat of tyranny was remote, ostracism seems to have been used as a way to decide between radically opposed policies. For instance, in 443 BC

443 BC

Year 443 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Macerinus and Barbatus...

Thucydides son of Milesias

Thucydides (politician)

Thucydides was a prominent politician of ancient Athens and the leader for a number of years of the powerful conservative faction. While it is likely he is related to the later historian Thucydides son of Olorus, the details are uncertain; maternal grandfather and grandson fits the available...

(not to be confused with the historian of the same name

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

) was ostracised. He led an aristocratic

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

opposition to Athenian imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

and in particular to Perikles'

Pericles

Pericles was a prominent and influential statesman, orator, and general of Athens during the city's Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars...

building program on the acropolis, which was funded by taxes created for the wars against Persia. By expelling Thucydides the Athenian people sent a clear message about the direction of Athenian policy. Similar but more controversial claims have been made about the ostracism of Cimon in 461 BC

461 BC

Year 461 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Gallus and Cornutus...

.

The motives of individual voting citizens cannot, of course, be known. Many of the surviving ostraka name people otherwise unattested. They may well be just someone the submitter disliked, and voted for in moment of private spite. As such, it may be seen as a secular, civic variant of Athenian curse

Curse

A curse is any expressed wish that some form of adversity or misfortune will befall or attach to some other entity—one or more persons, a place, or an object...

tablets, studied in scholarly literature under the Latin name defixiones, where small dolls were wrapped in lead sheets written with curses and then buried, sometimes stuck through with nails for good measure.

In one anecdote about Aristides, known as "the Just", who was ostracised in 482, an illiterate citizen, not recognising him, came up to ask him to write the name Aristides on his ostrakon. When Aristides asked why, the man replied it was because he was sick of hearing him being called "the Just". Perhaps merely the sense that someone had become too arrogant or prominent was enough to get someone's name onto an ostrakon.

Fall into disuse

The last ostracism, that of HyperbolosHyperbolos

Hyperbolus was an Athenian politician active during the first half of the Peloponnesian war, coming to particular prominence after the death of Cleon....

in or near 415 BC, is elaborately narrated by Plutarch in three separate lives: Hyperbolos is pictured urging the people to expel one of his rivals, but they, Nicias

Nicias

Nicias or Nikias was an Athenian politician and general during the period of the Peloponnesian War. Nicias was a member of the Athenian aristocracy because he had inherited a large fortune from his father, which was invested into the silver mines around Attica's Mt. Laurium...

and Alcibiades, laying aside their own hostility for a moment, use their combined influence to have him ostracised instead. According to Plutarch, the people then become disgusted with ostracism and abandon the procedure forever.

In part ostracism lapsed as a procedure at the end of the fifth century because it was replaced by the graphe paranomon

Graphē paranómōn

The graphē paranómōn , was a form of legal action believed to have been introduced at Athens under the democracy somewhere around the year 415 BC; it has been seen as a replacement for ostracism which fell into disuse around the same time.The name means "suit against contrary to the laws." The...

, a regular court action under which a much larger number of politicians might be targeted, instead of just one a year as with ostracism, and with greater severity. But it may already have come to seem like an anachronism as factional alliances organised around important men became increasingly less significant in the later period, and power was more specifically located in the interaction of the individual speaker with the power of the assembly and the courts. The threat to the democratic system in the late 5th century came not from tyranny but from oligarchic

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

coups, threats of which became prominent after two brief seizures of power, in 411

411 BC

Year 411 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Mugillanus and Rutilus...

by "the Four Hundred"

Athenian coup of 411 BC

The Athenian coup of 411 BC was a revolutionary movement during the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta that overthrew the democratic government of ancient Athens by replacing it with a short-lived oligarchy known as The Four Hundred....

and in 404 BC

404 BC

Year 404 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Tribunate of Volusus, Cossus, Fidenas, Ambustus, Maluginensis and Rutilus...

by "the Thirty"

Thirty Tyrants

The Thirty Tyrants were a pro-Spartan oligarchy installed in Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Contemporary Athenians referred to them simply as "the oligarchy" or "the Thirty" ; the expression "Thirty Tyrants" is due to later historians...

, which were not dependent on single powerful individuals. Ostracism was not an effective defence against the oligarchic threat and it was not so used.

Analogues

Other cities are known to have set up forms of ostracism on the Athenian model, namely MegaraMegara

Megara is an ancient city in Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken by Athens. Megara was one of the four districts of Attica, embodied in the four mythic sons of King...

, Miletos, Argos

Argos

Argos is a city and a former municipality in Argolis, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Argos-Mykines, of which it is a municipal unit. It is 11 kilometres from Nafplion, which was its historic harbour...

and Syracuse

Syracuse, Italy

Syracuse is a historic city in Sicily, the capital of the province of Syracuse. The city is notable for its rich Greek history, culture, amphitheatres, architecture, and as the birthplace of the preeminent mathematician and engineer Archimedes. This 2,700-year-old city played a key role in...

. In the last of these it was referred to as petalismos, because the names were written on olive

Olive

The olive , Olea europaea), is a species of a small tree in the family Oleaceae, native to the coastal areas of the eastern Mediterranean Basin as well as northern Iran at the south end of the Caspian Sea.Its fruit, also called the olive, is of major agricultural importance in the...

leaves. Little is known about these institutions. Furthermore, pottery shard

Sherd

In archaeology, a sherd is commonly a historic or prehistoric fragment of pottery, although the term is occasionally used to refer to fragments of stone and glass vessels as well....

s identified as ostraka have been found in Chersonesos Taurica, leading historians to the conclusion that a similar institution existed there as well, in spite of the silence of the ancient records on that count.

A similar modern practice is the recall election

Recall election

A recall election is a procedure by which voters can remove an elected official from office through a direct vote before his or her term has ended...

, in which the electoral body removes its representation from an elected officer. There have also been comparisons drawn in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

with appointment to the European Commission

European Commission

The European Commission is the executive body of the European Union. The body is responsible for proposing legislation, implementing decisions, upholding the Union's treaties and the general day-to-day running of the Union....

, which has the effect of removing political figures from the country for a period of years.

It is interesting to note that unlike under modern voting procedures, the Athenians did not have to adhere to a strict format for the inscribing of ostraka. Many extant ostraka show that it was possible to write expletives, short epigrams or cryptic injunctions beside the name of the candidate without invalidating the vote. For example:

- Kallixenes, son of Aristonimos, "the traitor".

- Archen, "lover of foreigners".

- Agasias, "the donkey".

- Megacles, "the adulterer".

Additional ancient references

From AristotleAristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

Constitution of the Athenians

Constitution of the Athenians

The Constitution of the Athenians is the name of either of two texts from Classical antiquity, one probably by Aristotle or a student of his, the other attributed to Xenophon, but not by him....

:

From Philochorus

Philochorus

Philochorus, of Athens, Greek historian during the 3rd century BC, , was a member of a priestly family. He was a seer and interpreter of signs, and a man of considerable influence....

, Atthis

From Plutarch's

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

'Lives':

- Life of Pericles 11-12

- Life of Pericles 14

- Life of Aristides 7

- Life of Cimon 17

- Life of Alcibiades 13

- Life of Nicias 11

- A list, differing slightly from that given above, of known ostracisms and many of the key Greek passages translated, from John Paul Adams's site at CSU Northridge.

Note that the ancient sources on ostracism are mostly 4th century or much later and often limited to brief descriptions such as notes by lexicographers. Most of the narrative and analytical passages of any length come from Plutarch writing five centuries later and with little sympathy for democratic practices. There are no contemporary accounts that can take one into the experiences of participants: a dense account of Athenian democracy can only be made on the basis of the much fuller sources available in the 4th century, especially the Attic orators

Attic orators

The ten Attic orators were considered the greatest orators and logographers of the classical era . They are included in the "Alexandrian Canon" compiled by Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace.-The Alexandrian "Canon of Ten":* Aeschines* Andocides* Antiphon* Demosthenes*...

, after ostracism had fallen into disuse. Most of such references are a 4th-century memory of the institution.

Additional modern references

- (1996). "Ostracism". Oxford Classical DictionaryOxford Classical Dictionary-Overview:The Oxford Classical Dictionary is considered to be the standard one-volume encyclopaedia in English of topics relating to the Ancient World and its civilizations. It was first published in 1949, edited by Max Cary with the assistance of H. J. Rose, H. P. Harvey, and A. Souter. A...

, 3rd edition. OxfordOxfordThe city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

. ISBN 0-19-860165-4. - Mabel Lang, (1990). Ostraka, Athens. ISBN 0-87661-225-7.

- Eugene Vanderpool, (1970). Ostracism at Athens, Cincinnati. ISBN 3-11-006637-8

- Rudi Thomsen, (1972). The Origins of Ostracism, A Synthesis, CopenhagenCopenhagenCopenhagen is the capital and largest city of Denmark, with an urban population of 1,199,224 and a metropolitan population of 1,930,260 . With the completion of the transnational Øresund Bridge in 2000, Copenhagen has become the centre of the increasingly integrating Øresund Region...

. - P.J. Rhodes, (1994). "The Ostracism of Hyberbolus'", Ritual, Finance, Politics: Athenian Democratic Accounts presented to David Lewis p. 85-99, editors. Robin Osborne, Simon Hornblower, (Oxford). ISBN 0-19-814992-1.

- Mogens Herman HansenMogens Herman HansenMogens Herman Hansen FBA is a Danish classical philologist who is one of the leading scholars in Athenian Democracy and the Polis....

, (1987). The Athenian Democracy in the age of Demosthenes, OxfordOxfordThe city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

. ISBN 0-8061-3143-8. - Josiah Ober, (1989), "Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens: Rhetoric", Ideology and the Power of the People, Princeton University PressPrinceton University Press-Further reading:* "". Artforum International, 2005.-External links:* * * * *...

. ISBN 0-691-02864-8. - Igor E. Surikov, (2006), "Остракизм в Афинах", Языки Славянских Культур. ISBN 5-9551-0136-5 (Russian, with English summary)