Olive Wharry

Encyclopedia

Olive Wharry was an English

artist, arson

ist and suffragist

who in 1913 was imprisoned with Lilian Lenton

for burning down the tea pavilion at Kew Gardens.

, the daughter of a doctor into a middle-class family and the only child of her father's first marriage; she had three much younger half-brothers and a half-sister from his second marriage. She grew up in London, then the family moved to Devon

when her father retired from medicine. On leaving school Wharry became an art student at the School of Art in Exeter

, and in 1906 she travelled around the world with her father and mother. She became active in the Women's Social and Political Union

in November 1910. She was also a member of the Church League for Women's Suffrage.

window-smashing campaign, and, after being released on bail guaranteed by Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Mrs Saul Solomon, was sentenced to two months' imprisonment. During this sentence and the others that followed she kept a scrapbook which includes the autographs of fellow Suffragette

s. This scrapbook was an exhibit in the British Library

's Taking Liberties exhibition (2008-9).

In March 1912 Wharry was arrested again after more window-smashing and was sentenced to six months imprisonment in Winson Green Prison

in Birmingham

. She took part in a hunger strike

and was released in July 1912, before completing her sentence. In November 1912 she was arrested as "Joyce Locke" with three other Suffragettes in Aberdeen

after being involved in a scuffle during a meeting at which Lloyd George

was speaking. Being sentenced to five days in prison, she managed to smash her cell windows.

On 7 March 1913, aged 27, she and Lilian Lenton

On 7 March 1913, aged 27, she and Lilian Lenton

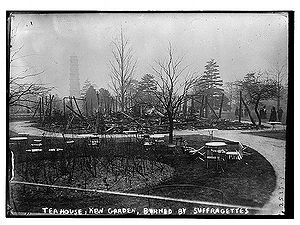

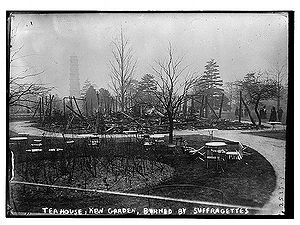

were sent to Holloway Prison for setting fire to the tea pavilion at Kew Gardens, causing £900 worth of damage. The pavilion's owners had only insured it for £500. During her trial at the Old Bailey

Wharry was again charged under the assumed name "Joyce Locke" and regarded the proceedings as a "good joke". She stated that she and Lenton had checked that the tea pavilion was empty before setting fire to it. She added that she had believed that the pavilion belonged to the Crown, and that she wished for the two women who actually owned it to understand that she was fighting a war, and that in a war even men combatants had to suffer. When Wharry was sentenced to eighteen months with costs, refusing to pay she cried out "I will refuse to do so. You can send me to prison, but I will never pay the costs".

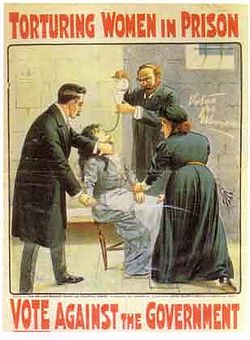

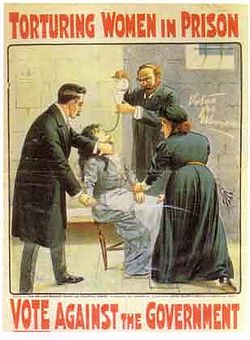

In prison Wharry went on hunger strike for 32 days, passing her food to other prisoners, apparently unnoticed by the warders. Wharry said that during her time in prison her weight had plummeted from .

Wharry was arrested and imprisoned eight times between 1910 and 1914 for her part in various WSPU

Wharry was arrested and imprisoned eight times between 1910 and 1914 for her part in various WSPU

window-smashing campaigns, sometimes under the name "Phyllis North", sometimes as "Joyce Locke". Each of her prison sentences were characterised by her going on hunger strike

, being force-fed and then released under what became known as the Cat and Mouse Act

.

In May 1914 she was sentenced to a week in prison after taking part in a deputation to King George V

. It was a matter of honour to Wharry not to complete any prison sentence, and, after again going on hunger strike

, she was released after three days. In June 1914 she was arrested at Carnarvon

after breaking windows at Criccieth

during a meeting held by Lloyd George

. Being held on remand, she again went on hunger strike and was released. As "Phyllis North" she was arrested in Liverpool

and was brought back to Carnarvon where she received a prison sentence of three months.

Wharry was sent to Holloway Prison to complete this sentence, and where she was held, on hunger strike

, in solitary confinement

. Home Office

reports show that some of the doctors who treated her at Holloway thought she was insane, but her scrapbook, which documents her time in this prison and in various other prisons around the country, suggests otherwise. It is full of drawings of prison life, satirical poems, autograph

s of other suffragette

s and a photograph of herself and Lilian Lenton

in the dock during their trial for the arson attack on Kew Gardens of 1913.

The pages in her scrapbook, held by the British Library

in London, also record her weight loss on release from prison, and contains newspaper cuttings of a policeman carrying her bags on her release from prison and a burnt down tea pavilion at Kew Gardens. Wharry was released into the care of Dr. Flora Murray

on 10 August 1913 under the Government's amnesty of suffrage prisoners.

Constance Bryer (1870–1952) an executor

of her 1946 will, in which she requested that her body be cremated and her ashes scattered on "the high open spaces of the Moor between Exeter

and Whitstone

". In her will she left Bryer an annuity

of £200, her hunger strike

medal and some of her etchings and books. Both Wharry and Byer's hunger strike medals remain together in a private collection.

Olive Wharry died at the age of 61.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

artist, arson

Arson

Arson is the crime of intentionally or maliciously setting fire to structures or wildland areas. It may be distinguished from other causes such as spontaneous combustion and natural wildfires...

ist and suffragist

Suffragette

"Suffragette" is a term coined by the Daily Mail newspaper as a derogatory label for members of the late 19th and early 20th century movement for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, in particular members of the Women's Social and Political Union...

who in 1913 was imprisoned with Lilian Lenton

Lilian Lenton

Lilian Ida Lenton was an English dancer, suffragist, arsonist, and winner of a French Red Cross medal for her service as an Orderly in World War I.-Early years:...

for burning down the tea pavilion at Kew Gardens.

Early life

Olive Wharry was born in LondonLondon

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, the daughter of a doctor into a middle-class family and the only child of her father's first marriage; she had three much younger half-brothers and a half-sister from his second marriage. She grew up in London, then the family moved to Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

when her father retired from medicine. On leaving school Wharry became an art student at the School of Art in Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

, and in 1906 she travelled around the world with her father and mother. She became active in the Women's Social and Political Union

Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union was the leading militant organisation campaigning for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom...

in November 1910. She was also a member of the Church League for Women's Suffrage.

1911 to 1913

In November 1911 Wharry was arrested for taking part in a WSPUWomen's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union was the leading militant organisation campaigning for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom...

window-smashing campaign, and, after being released on bail guaranteed by Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and Mrs Saul Solomon, was sentenced to two months' imprisonment. During this sentence and the others that followed she kept a scrapbook which includes the autographs of fellow Suffragette

Suffragette

"Suffragette" is a term coined by the Daily Mail newspaper as a derogatory label for members of the late 19th and early 20th century movement for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, in particular members of the Women's Social and Political Union...

s. This scrapbook was an exhibit in the British Library

British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom, and is the world's largest library in terms of total number of items. The library is a major research library, holding over 150 million items from every country in the world, in virtually all known languages and in many formats,...

's Taking Liberties exhibition (2008-9).

In March 1912 Wharry was arrested again after more window-smashing and was sentenced to six months imprisonment in Winson Green Prison

Birmingham (HM Prison)

HM Prison Birmingham is a Category B/C men's prison, located in the Winson Green area of Birmingham, England. The prison was formally operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service...

in Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is the most populous British city outside the capital London, with a population of 1,036,900 , and lies at the heart of the West Midlands conurbation, the second most populous urban area in the United Kingdom with a...

. She took part in a hunger strike

Hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance or pressure in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke feelings of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most hunger strikers will take liquids but not...

and was released in July 1912, before completing her sentence. In November 1912 she was arrested as "Joyce Locke" with three other Suffragettes in Aberdeen

Aberdeen

Aberdeen is Scotland's third most populous city, one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas and the United Kingdom's 25th most populous city, with an official population estimate of ....

after being involved in a scuffle during a meeting at which Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

was speaking. Being sentenced to five days in prison, she managed to smash her cell windows.

Kew Gardens arson

Lilian Lenton

Lilian Ida Lenton was an English dancer, suffragist, arsonist, and winner of a French Red Cross medal for her service as an Orderly in World War I.-Early years:...

were sent to Holloway Prison for setting fire to the tea pavilion at Kew Gardens, causing £900 worth of damage. The pavilion's owners had only insured it for £500. During her trial at the Old Bailey

Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court in England and Wales, commonly known as the Old Bailey from the street in which it stands, is a court building in central London, one of a number of buildings housing the Crown Court...

Wharry was again charged under the assumed name "Joyce Locke" and regarded the proceedings as a "good joke". She stated that she and Lenton had checked that the tea pavilion was empty before setting fire to it. She added that she had believed that the pavilion belonged to the Crown, and that she wished for the two women who actually owned it to understand that she was fighting a war, and that in a war even men combatants had to suffer. When Wharry was sentenced to eighteen months with costs, refusing to pay she cried out "I will refuse to do so. You can send me to prison, but I will never pay the costs".

In prison Wharry went on hunger strike for 32 days, passing her food to other prisoners, apparently unnoticed by the warders. Wharry said that during her time in prison her weight had plummeted from .

Other prison sentences

Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union was the leading militant organisation campaigning for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom...

window-smashing campaigns, sometimes under the name "Phyllis North", sometimes as "Joyce Locke". Each of her prison sentences were characterised by her going on hunger strike

Hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance or pressure in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke feelings of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most hunger strikers will take liquids but not...

, being force-fed and then released under what became known as the Cat and Mouse Act

Cat and Mouse Act

The Prisoners Act 1913 was an Act of Parliament passed in Britain under Herbert Henry Asquith's Liberal government in 1913...

.

In May 1914 she was sentenced to a week in prison after taking part in a deputation to King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

. It was a matter of honour to Wharry not to complete any prison sentence, and, after again going on hunger strike

Hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance or pressure in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke feelings of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most hunger strikers will take liquids but not...

, she was released after three days. In June 1914 she was arrested at Carnarvon

Carnarvon

Carnarvon and Caernarvon are older forms of the name of the town in North Wales currently known as Caernarfon. The older names, in place for centuries, were anglicised phonetic spellings; since the 1970s the Welsh spelling has been generally adopted...

after breaking windows at Criccieth

Criccieth

Criccieth is a town and community on Cardigan Bay, in the Eifionydd area of Gwynedd in Wales. The town lies west of Porthmadog, east of Pwllheli and south of Caernarfon. It has a population of 1,826....

during a meeting held by Lloyd George

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor OM, PC was a British Liberal politician and statesman...

. Being held on remand, she again went on hunger strike and was released. As "Phyllis North" she was arrested in Liverpool

Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough of Merseyside, England, along the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary. It was founded as a borough in 1207 and was granted city status in 1880...

and was brought back to Carnarvon where she received a prison sentence of three months.

Wharry was sent to Holloway Prison to complete this sentence, and where she was held, on hunger strike

Hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance or pressure in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke feelings of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most hunger strikers will take liquids but not...

, in solitary confinement

Solitary confinement

Solitary confinement is a special form of imprisonment in which a prisoner is isolated from any human contact, though often with the exception of members of prison staff. It is sometimes employed as a form of punishment beyond incarceration for a prisoner, and has been cited as an additional...

. Home Office

Home Office

The Home Office is the United Kingdom government department responsible for immigration control, security, and order. As such it is responsible for the police, UK Border Agency, and the Security Service . It is also in charge of government policy on security-related issues such as drugs,...

reports show that some of the doctors who treated her at Holloway thought she was insane, but her scrapbook, which documents her time in this prison and in various other prisons around the country, suggests otherwise. It is full of drawings of prison life, satirical poems, autograph

Autograph

An autograph is a document transcribed entirely in the handwriting of its author, as opposed to a typeset document or one written by an amanuensis or a copyist; the meaning overlaps with that of the word holograph.Autograph also refers to a person's artistic signature...

s of other suffragette

Suffragette

"Suffragette" is a term coined by the Daily Mail newspaper as a derogatory label for members of the late 19th and early 20th century movement for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, in particular members of the Women's Social and Political Union...

s and a photograph of herself and Lilian Lenton

Lilian Lenton

Lilian Ida Lenton was an English dancer, suffragist, arsonist, and winner of a French Red Cross medal for her service as an Orderly in World War I.-Early years:...

in the dock during their trial for the arson attack on Kew Gardens of 1913.

The pages in her scrapbook, held by the British Library

British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom, and is the world's largest library in terms of total number of items. The library is a major research library, holding over 150 million items from every country in the world, in virtually all known languages and in many formats,...

in London, also record her weight loss on release from prison, and contains newspaper cuttings of a policeman carrying her bags on her release from prison and a burnt down tea pavilion at Kew Gardens. Wharry was released into the care of Dr. Flora Murray

Flora Murray

Dr. Flora Murray, M.D. was a medical pioneer and a member of the Women's Social and Political Union suffragettes.Murray trained at the London School of Medicine for Women and finished her course at Durham. She then worked in Scotland before returning to London in 1905...

on 10 August 1913 under the Government's amnesty of suffrage prisoners.

Death and legacy

Wharry made fellow SuffragetteSuffragette

"Suffragette" is a term coined by the Daily Mail newspaper as a derogatory label for members of the late 19th and early 20th century movement for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, in particular members of the Women's Social and Political Union...

Constance Bryer (1870–1952) an executor

Executor

An executor, in the broadest sense, is one who carries something out .-Overview:...

of her 1946 will, in which she requested that her body be cremated and her ashes scattered on "the high open spaces of the Moor between Exeter

Exeter

Exeter is a historic city in Devon, England. It lies within the ceremonial county of Devon, of which it is the county town as well as the home of Devon County Council. Currently the administrative area has the status of a non-metropolitan district, and is therefore under the administration of the...

and Whitstone

Whitstone

Whitstone is a village and civil parish in east Cornwall, United Kingdom. It is roughly halfway between the towns of Bude and Launceston.-History:...

". In her will she left Bryer an annuity

Annuity (European financial arrangements)

An annuity can be defined as a financial contract which provides an income stream in return for an initial payment with specific parameters. It is the opposite of a settlement funding...

of £200, her hunger strike

Hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance or pressure in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke feelings of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most hunger strikers will take liquids but not...

medal and some of her etchings and books. Both Wharry and Byer's hunger strike medals remain together in a private collection.

Olive Wharry died at the age of 61.

External links

- http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/takingliberties/staritems/115olivewharryscrapbook.htmlWharry on 'Taking Liberties' - British LibraryBritish LibraryThe British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom, and is the world's largest library in terms of total number of items. The library is a major research library, holding over 150 million items from every country in the world, in virtually all known languages and in many formats,...

website] - The Outrage at Kew Gardens: Sentence on Olive Wharry The Morning Post 8 March 1913

- http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/visual_arts/article5024130.eceWharry in the British Library's Taking Liberties exhibition The TimesThe TimesThe Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

28 October 2008]