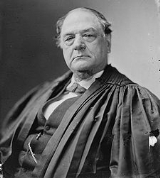

Noah Haynes Swayne

Encyclopedia

Noah Haynes Swayne was an American jurist

and politician. He was the first Republican

appointed as a justice to the United States Supreme Court.

in the uppermost reaches of the Shenandoah Valley

, approximately 100 miles (160.9 km) northwest of Washington D.C. He was the youngest of nine children of Joshua Swayne and Rebecca (Smith) Swayne. He was a descendant of Francis Swayne, who emigrated from England in 1710 and settled near Philadelphia. After his father died in 1809, Noah was educated locally until enrolling in Jacob Mendendhall's Academy in Waterford, Virginia

, a respected Quaker school 1817-18. He began to study medicine in Alexandria, Virginia

, but abandoned this pursuit after his teacher Dr. George Thornton died in 1819. Despite his family having no money to support his continued education, he read law under John Scott and Francis Brooks in Warrenton, Virginia

, and was admitted to the Virginia Bar in 1823. A devout Quaker (and to date the only Quaker to serve on the Supreme Court), Swayne was deeply opposed to slavery, and in 1824 he left Virginia

for the free state of Ohio

. His abolitionist sentiments caused him to move to Ohio.

He began a private practice in Coshocton

and, in 1825, was elected Coshocton County

Attorney. Four years later he was elected to the Ohio state legislature. In 1830 he was appointed U.S. Attorney

for Ohio by Andrew Jackson

, and moved to Columbus

to take up the new position.

While serving as U.S. Attorney, Swayne was elected in 1834 to the Columbus city council, and in 1836 to the state legislature. As U.S. Attorney, Swayne became close friends with Supreme Court justice John McLean

. McLean, by the end of his career, was a strong Republican

, and when the party was formed in 1855 Swayne had become an early member and political organizer.

In 1835, as escalating tensions in the boundary dispute between Ohio and Michigan Territory

(the Toledo War

) threatened to erupt into violent conflict, Ohio Governor Robert Lucas

dispatched Swayne, along with former Congressman William Allen

and David T. Disney

, to Washington D.C. to confer with President Andrew Jackson

. The delegation presented Ohio's case and urged the President to act swiftly to address the situation.

case. He sought the Republican nomination for President

in 1860, losing to Abraham Lincoln

. However, he recommended to Lincoln on a number of occasions that Swayne be nominated to replace him on the court. This proved timely; McLean died shortly after Lincoln's inauguration, in April 1861. As the American Civil War

began, Swayne campaigned for the vacant seat, lobbying several Ohio members of Congress for their support. As the Supreme Court media itself notes: "Swayne satisfied Lincoln's criteria for appointment: commitment to the Union, slavery opponent, geographically correct."

It is also believed that Swayne had also represented fugitive slaves in court. So eight months after McLean's death, Swayne was nominated in January 1862.

In the Slaughterhouse Cases

, 83 U.S. 36 (1873) -- a pivotal decision on the meaning of Section 1 of the relatively new Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution

-- Swayne dissented with Justices Stephen Field

and Joseph Bradley. Field's dissent was important, and presaged later decisions broadening the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, four years later Swayne joined the majority in Munn v. Illinois

, with Field and Bradley still dissenting.

Swayne's potential judicial greatness failed to materialize. He was first of President Lincoln's five appointments to the Supreme Court: Noah Hayes Swayne – 1862; Samuel Freeman Miller

– 1862; David Davis

– 1862; Stephen Johnson Field

– 1863; and Salmon P. Chase

– Chief Justice

– 1864. He is also said to have been "the weakest". His main distinction was his staunch judicial support of the president's war measures: the Union blockade (Prize Cases

, 67 U.S. 635 (1862)); issuance of paper money

(i.e., greenbacks); and support for the presidential prerogative to declare martial law

(Ex Parte Milligan

, 71 U.S. 2 (1866)).

He is most famous for his majority opinion in Springer v. United States

, 102 U.S. 586

(1881), which upheld the Federal income tax

imposed under the Revenue Act of 1864

.

In Gelpcke v. Dubuque 68 U.S. 175

(1864) Swayne wrote the majority opinion, repudiating a claim that the Iowa constitution could impair legal obligations to bondholders. When contracts are made on the basis of trust in past judicial decisions those contracts could not be impaired by any subsequent construction of the law. "We shall never immolate truth, justice, and the law, because a state tribunal has erected the altar and decreed the sacrifice." He strongly supported "the contractual rights of railroad bond holders, "even in the face of repudiation sanctioned both by the Iowa

state legislature and state supreme court

. Obligations sacred to law are not to be destroyed simply because 'a state tribunal has erected the altar and decreed the sacrifice.'” For a later decision on impairment of contracts, compare Lochner v. New York

, 198 U.S. 45 (1905).

Swayne remained on the court until 1881, twice lobbying unsuccessfully to be elevated to the position of Chief Justice (after the death of Roger Taney in 1864 and Salmon Chase in 1873).

After his retirement, Swayne returned to Ohio.

, he finally agreed to retire on the condition that his friend and fellow Ohio attorney Stanley Matthews

replace him.

His son, Wager Swayne

, served in the American Civil War

, rose to the rank of Major General

, served as the military governor of Alabama after the Civil War, and subsequently founded law firms in Toledo, Ohio and New York City. Wager's son, named Noah Hayes Swayne after his grandfather, was president of Burns Brothers, the largest coal distributor in the U.S. when he retired in September 1932. Another of Wager's sons, Alfred Harris Swayne, was vice president of General Motors Corporation.

Another of Justice Swayne's sons, Noah Swayne, was a lawyer in Toledo and donated the land for Swayne Field

, the former field for the Toledo Mud Hens

baseball team.

Justice Swayne's remains were buried at the Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

The Georgetown graveyard overlooks Rock Creek, and is shared with: Chief Justice Edward Douglass White

; and "almost-Justice" Edwin M. Stanton

(President Ulysses S. Grant

's nomination of him was confirmed by the Senate, but Stanton died before he could be sworn in). Also, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase

was buried there, but his body was transferred after 14 years to Cincinnati, Ohio

's Spring Grove Cemetery

.

The bulk of his legal papers are located at the Ohio Historical Society

, Columbus, Ohio

. Other papers are at: Detroit Public Library

, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit, Michigan

; Chicago Historical Society, Chicago, Illinois; Library of Congress

, Manuscript and Prints & Photographs Divisions, Washington, D.C.

; State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin

; University of Louisville

Louis D. Brandeis School of Law

, Louisville, Kentucky

; and University of Toledo

, Canaday Center, Manuscripts: Politics & Government, Toledo, Ohio

.

Jurist

A jurist or jurisconsult is a professional who studies, develops, applies, or otherwise deals with the law. The term is widely used in American English, but in the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth countries it has only historical and specialist usage...

and politician. He was the first Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

appointed as a justice to the United States Supreme Court.

Birth and early life

Swayne was born in Frederick County, VirginiaFrederick County, Virginia

Frederick County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is included in the Winchester, Virginia-West Virginia Metropolitan Statistical Area. It was formed in 1743 by the splitting of Orange County. For ten years it was the home of George Washington. As of 2010, the population was...

in the uppermost reaches of the Shenandoah Valley

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley is both a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and West Virginia in the United States. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians , to the north by the Potomac River...

, approximately 100 miles (160.9 km) northwest of Washington D.C. He was the youngest of nine children of Joshua Swayne and Rebecca (Smith) Swayne. He was a descendant of Francis Swayne, who emigrated from England in 1710 and settled near Philadelphia. After his father died in 1809, Noah was educated locally until enrolling in Jacob Mendendhall's Academy in Waterford, Virginia

Waterford, Virginia

Waterford is an unincorporated village in the Catoctin Valley of Loudoun County, Virginia, located along Catoctin Creek. Waterford is northwest of Washington, D.C., and northwest of Leesburg...

, a respected Quaker school 1817-18. He began to study medicine in Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of 2009, the city had a total population of 139,966. Located along the Western bank of the Potomac River, Alexandria is approximately six miles south of downtown Washington, D.C.Like the rest of northern Virginia, as well as...

, but abandoned this pursuit after his teacher Dr. George Thornton died in 1819. Despite his family having no money to support his continued education, he read law under John Scott and Francis Brooks in Warrenton, Virginia

Warrenton, Virginia

Warrenton is a town in Fauquier County, Virginia, United States. The population was 6,670 at the 2000 census, and 14,634 at the 2010 estimate. It is the county seat of Fauquier County. Public schools in the town include Fauquier High School, Warrenton Middle School, Taylor Middle School and two...

, and was admitted to the Virginia Bar in 1823. A devout Quaker (and to date the only Quaker to serve on the Supreme Court), Swayne was deeply opposed to slavery, and in 1824 he left Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

for the free state of Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

. His abolitionist sentiments caused him to move to Ohio.

He began a private practice in Coshocton

Coshocton, Ohio

Coshocton is a city in and the county seat of Coshocton County, Ohio, United States. The population of the city was 11,682 at the 2000 census. The Walhonding River and the Tuscarawas River meet in Coshocton to form the Muskingum River....

and, in 1825, was elected Coshocton County

Coshocton County, Ohio

Coshocton County is a county located in the state of Ohio, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 36,901. Its county seat is Coshocton. Its name comes from the Delaware Indian language and has been translated as "union of waters" or "black bear crossing".The Coshocton...

Attorney. Four years later he was elected to the Ohio state legislature. In 1830 he was appointed U.S. Attorney

United States Attorney

United States Attorneys represent the United States federal government in United States district court and United States court of appeals. There are 93 U.S. Attorneys stationed throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands...

for Ohio by Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

, and moved to Columbus

Columbus, Ohio

Columbus is the capital of and the largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio. The broader metropolitan area encompasses several counties and is the third largest in Ohio behind those of Cleveland and Cincinnati. Columbus is the third largest city in the American Midwest, and the fifteenth largest city...

to take up the new position.

While serving as U.S. Attorney, Swayne was elected in 1834 to the Columbus city council, and in 1836 to the state legislature. As U.S. Attorney, Swayne became close friends with Supreme Court justice John McLean

John McLean

John McLean was an American jurist and politician who served in the United States Congress, as U.S. Postmaster General, and as a justice on the Ohio and U.S...

. McLean, by the end of his career, was a strong Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

, and when the party was formed in 1855 Swayne had become an early member and political organizer.

In 1835, as escalating tensions in the boundary dispute between Ohio and Michigan Territory

Michigan Territory

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan...

(the Toledo War

Toledo War

The Toledo War , also known as the Michigan-Ohio War, was the almost entirely bloodless boundary dispute between the U.S. state of Ohio and the adjoining territory of Michigan....

) threatened to erupt into violent conflict, Ohio Governor Robert Lucas

Robert Lucas (governor)

Robert Lucas was the 12th Governor of the U.S. state of Ohio, serving from 1832 to 1836. He served as the first Governor of Iowa Territory from 1838 to 1841.-Early life:...

dispatched Swayne, along with former Congressman William Allen

William Allen (governor)

William Allen was an Democratic Representative, Senator and 31st Governor of Ohio. He moved to the U.S. state of Ohio after his parents died, residing in Chillicothe, Ohio....

and David T. Disney

David T. Disney

David Tiernan Disney was a U.S. Representative from Ohio.Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Disney moved with his parents to Ohio in 1807.He attended the common schools.He studied law....

, to Washington D.C. to confer with President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

. The delegation presented Ohio's case and urged the President to act swiftly to address the situation.

Supreme Court service

McLean was one of two dissenters in the Dred ScottDred Scott

Dred Scott , was an African-American slave in the United States who unsuccessfully sued for his freedom and that of his wife and their two daughters in the Dred Scott v...

case. He sought the Republican nomination for President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

in 1860, losing to Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

. However, he recommended to Lincoln on a number of occasions that Swayne be nominated to replace him on the court. This proved timely; McLean died shortly after Lincoln's inauguration, in April 1861. As the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

began, Swayne campaigned for the vacant seat, lobbying several Ohio members of Congress for their support. As the Supreme Court media itself notes: "Swayne satisfied Lincoln's criteria for appointment: commitment to the Union, slavery opponent, geographically correct."

It is also believed that Swayne had also represented fugitive slaves in court. So eight months after McLean's death, Swayne was nominated in January 1862.

In the Slaughterhouse Cases

Slaughterhouse Cases

The Slaughter-House Cases, were the first United States Supreme Court interpretation of the relatively new Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution...

, 83 U.S. 36 (1873) -- a pivotal decision on the meaning of Section 1 of the relatively new Fourteenth Amendment

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

to the Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

-- Swayne dissented with Justices Stephen Field

Stephen Field

Professor Stephen P Field, FRCGP is a British doctor and general practitioner, former Chairman of the Royal College of General Practitioners and Chairman of the Department of Health's Inclusion Board. In 2011, the United Kingdom government appointed him to chair the NHS Future Forum formed to...

and Joseph Bradley. Field's dissent was important, and presaged later decisions broadening the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, four years later Swayne joined the majority in Munn v. Illinois

Munn v. Illinois

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113 , was a United States Supreme Court case dealing with corporate rates and agriculture. The Munn case allowed states to regulate certain businesses within their borders, including railroads, and is commonly regarded as a milestone in the growth of federal government...

, with Field and Bradley still dissenting.

Swayne's potential judicial greatness failed to materialize. He was first of President Lincoln's five appointments to the Supreme Court: Noah Hayes Swayne – 1862; Samuel Freeman Miller

Samuel Freeman Miller

Samuel Freeman Miller was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1862–1890. He was a physician and lawyer.-Early life and education:...

– 1862; David Davis

David Davis

David Davis may refer to:*David Davis , Liberal member of the Victorian Legislative Council*David Davis , British Conservative Member of Parliament, Conservative leadership candidate in 2001 and 2005*David Davis , head of the BBC's Children's Hour*David Davis ,...

– 1862; Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897...

– 1863; and Salmon P. Chase

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase was an American politician and jurist who served as U.S. Senator from Ohio and the 23rd Governor of Ohio; as U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Abraham Lincoln; and as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.Chase was one of the most prominent members...

– Chief Justice

Chief Justice of the United States

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

– 1864. He is also said to have been "the weakest". His main distinction was his staunch judicial support of the president's war measures: the Union blockade (Prize Cases

Prize Cases

Prize Cases – 67 U.S. 635 – was a case argued before the Supreme Court of the United States in 1862 during the American Civil War. The Supreme Court's decision declared constitutional the blockade of the Southern ports ordered by President Abraham Lincoln...

, 67 U.S. 635 (1862)); issuance of paper money

Paper Money

Paper Money is the second album by the band Montrose. It was released in 1974 and was the band's last album to feature Sammy Hagar as lead vocalist.-History:...

(i.e., greenbacks); and support for the presidential prerogative to declare martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

(Ex Parte Milligan

Ex parte Milligan

Ex parte Milligan, , was a United States Supreme Court case that ruled that the application of military tribunals to citizens when civilian courts are still operating is unconstitutional. It was also controversial because it was one of the first cases after the end of the American Civil...

, 71 U.S. 2 (1866)).

He is most famous for his majority opinion in Springer v. United States

Springer v. United States

Springer v. United States, 102 U.S. 586 , was a case in which the United States Supreme Court upheld the Federal income tax imposed under the Revenue Act of 1864.- Background :...

, 102 U.S. 586

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1881), which upheld the Federal income tax

Income tax

An income tax is a tax levied on the income of individuals or businesses . Various income tax systems exist, with varying degrees of tax incidence. Income taxation can be progressive, proportional, or regressive. When the tax is levied on the income of companies, it is often called a corporate...

imposed under the Revenue Act of 1864

Revenue Act of 1864

The Internal Revenue Act of 1864, 13 Stat. 223 , increased the income tax rates established by the Internal Revenue Act of 1862. The measure was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln.-Provisions:...

.

In Gelpcke v. Dubuque 68 U.S. 175

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

(1864) Swayne wrote the majority opinion, repudiating a claim that the Iowa constitution could impair legal obligations to bondholders. When contracts are made on the basis of trust in past judicial decisions those contracts could not be impaired by any subsequent construction of the law. "We shall never immolate truth, justice, and the law, because a state tribunal has erected the altar and decreed the sacrifice." He strongly supported "the contractual rights of railroad bond holders, "even in the face of repudiation sanctioned both by the Iowa

Iowa

Iowa is a state located in the Midwestern United States, an area often referred to as the "American Heartland". It derives its name from the Ioway people, one of the many American Indian tribes that occupied the state at the time of European exploration. Iowa was a part of the French colony of New...

state legislature and state supreme court

Supreme court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of many legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, instance court, judgment court, high court, or apex court...

. Obligations sacred to law are not to be destroyed simply because 'a state tribunal has erected the altar and decreed the sacrifice.'” For a later decision on impairment of contracts, compare Lochner v. New York

Lochner v. New York

Lochner vs. New York, , was a landmark United States Supreme Court case that held a "liberty of contract" was implicit in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The case involved a New York law that limited the number of hours that a baker could work each day to ten, and limited the...

, 198 U.S. 45 (1905).

Swayne remained on the court until 1881, twice lobbying unsuccessfully to be elevated to the position of Chief Justice (after the death of Roger Taney in 1864 and Salmon Chase in 1873).

After his retirement, Swayne returned to Ohio.

Retirement, death and legacy

Swayne is not regarded as a particularly distinguished justice. He wrote few opinions, usually signing on to opinions written by others, and remained on the court well past his physical prime, being quite infirm at his retirement. Under pressure from President Rutherford B. HayesRutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

, he finally agreed to retire on the condition that his friend and fellow Ohio attorney Stanley Matthews

Thomas Stanley Matthews

Thomas Stanley Matthews , known as Stanley Matthews, was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from May 1881 to his death in 1889. Matthews was the Court's 46th justice...

replace him.

His son, Wager Swayne

Wager Swayne

Wager Swayne was a Union Army general during the American Civil War who received America's highest military decoration the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Second Battle of Corinth...

, served in the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, rose to the rank of Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

, served as the military governor of Alabama after the Civil War, and subsequently founded law firms in Toledo, Ohio and New York City. Wager's son, named Noah Hayes Swayne after his grandfather, was president of Burns Brothers, the largest coal distributor in the U.S. when he retired in September 1932. Another of Wager's sons, Alfred Harris Swayne, was vice president of General Motors Corporation.

Another of Justice Swayne's sons, Noah Swayne, was a lawyer in Toledo and donated the land for Swayne Field

Swayne Field

Swayne Field was a minor league baseball park in Toledo, Ohio. It was the home of the Toledo Mud Hens from July 3, 1909, until the club disbanded after the 1955 season. It was also home to a short-lived entry in the South-Michigan League in 1914....

, the former field for the Toledo Mud Hens

Toledo Mud Hens

The Toledo Mud Hens are a minor league baseball team located in Toledo, Ohio. The Mud Hens play in the International League, and are affiliated with the major league baseball team the Detroit Tigers, based approximately 50 miles to the north of Toledo. The current team is one of several...

baseball team.

Justice Swayne's remains were buried at the Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

The Georgetown graveyard overlooks Rock Creek, and is shared with: Chief Justice Edward Douglass White

Edward Douglass White

Edward Douglass White, Jr. , American politician and jurist, was a United States senator, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court and the ninth Chief Justice of the United States. He was best known for formulating the Rule of Reason standard of antitrust law. He also sided with the...

; and "almost-Justice" Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton was an American lawyer and politician who served as Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during the American Civil War from 1862–1865...

(President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

's nomination of him was confirmed by the Senate, but Stanton died before he could be sworn in). Also, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase

Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase was an American politician and jurist who served as U.S. Senator from Ohio and the 23rd Governor of Ohio; as U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Abraham Lincoln; and as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.Chase was one of the most prominent members...

was buried there, but his body was transferred after 14 years to Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio. Cincinnati is the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located to north of the Ohio River at the Ohio-Kentucky border, near Indiana. The population within city limits is 296,943 according to the 2010 census, making it Ohio's...

's Spring Grove Cemetery

Spring Grove Cemetery

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum is a nonprofit garden cemetery and arboretum located at 4521 Spring Grove Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio. It is the second largest cemetery in the United States and is recognized as a U.S. National Historic Landmark....

.

The bulk of his legal papers are located at the Ohio Historical Society

Ohio Historical Society

The Ohio Historical Society is a non-profit organization incorporated in 1885 as The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society "to promote a knowledge of archaeology and history, especially in Ohio"...

, Columbus, Ohio

Columbus, Ohio

Columbus is the capital of and the largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio. The broader metropolitan area encompasses several counties and is the third largest in Ohio behind those of Cleveland and Cincinnati. Columbus is the third largest city in the American Midwest, and the fifteenth largest city...

. Other papers are at: Detroit Public Library

Detroit Public Library

The Detroit Public Library is the second largest library system in Michigan by volumes held , and is the 20th largest library system in the United States. It is composed of a Main Library on Woodward Avenue, which houses DPL administration offices, and twenty-three branch locations across the city...

, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit, Michigan

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit is the major city among the primary cultural, financial, and transportation centers in the Metro Detroit area, a region of 5.2 million people. As the seat of Wayne County, the city of Detroit is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan and serves as a major port on the Detroit River...

; Chicago Historical Society, Chicago, Illinois; Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress is the research library of the United States Congress, de facto national library of the United States, and the oldest federal cultural institution in the United States. Located in three buildings in Washington, D.C., it is the largest library in the world by shelf space and...

, Manuscript and Prints & Photographs Divisions, Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

; State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin

Madison, Wisconsin

Madison is the capital of the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Dane County. It is also home to the University of Wisconsin–Madison....

; University of Louisville

University of Louisville

The University of Louisville is a public university in Louisville, Kentucky. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one of the first universities chartered west of the Allegheny Mountains. The university is mandated by the Kentucky General...

Louis D. Brandeis School of Law

Louis D. Brandeis School of Law

The Louis D. Brandeis School of Law is the law school of the University of Louisville. Established in 1846, it is the oldest law school in Kentucky and the fifth oldest in the country in continuous operation. The law school is named after Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis, who served on the Supreme...

, Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

; and University of Toledo

University of Toledo

The University of Toledo is a public university in Toledo, Ohio, United States. The Carnegie Foundation classified the university as "Doctoral/Research Extensive."-National recognition:...

, Canaday Center, Manuscripts: Politics & Government, Toledo, Ohio

Toledo, Ohio

Toledo is the fourth most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Lucas County. Toledo is in northwest Ohio, on the western end of Lake Erie, and borders the State of Michigan...

.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United StatesDemographics of the Supreme Court of the United StatesThe demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States encompass the gender, ethnic, religious, geographic, and economic backgrounds of the 112 justices appointed to the Supreme Court. Certain of these characteristics have been raised as an issue since the Court was established in 1789. For its...

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Chase Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Taney Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Waite Court

- Wager SwayneWager SwayneWager Swayne was a Union Army general during the American Civil War who received America's highest military decoration the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Second Battle of Corinth...

Further reading

- Barnes, William Horatio. (1875) "Noah H. Swayne, Associate Justice. -- In The Supreme Court of the United States", by W. Barnes. Part II of Barnes's Illustrated Cyclopedia of the American Government.

- Bibliography, biography and location of papers, Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.