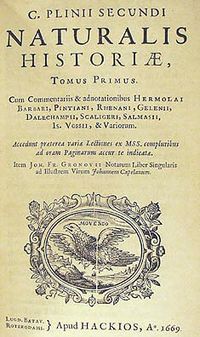

Naturalis Historia

Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia

An encyclopedia is a type of reference work, a compendium holding a summary of information from either all branches of knowledge or a particular branch of knowledge....

published circa

Circa

Circa , usually abbreviated c. or ca. , means "approximately" in the English language, usually referring to a date...

AD 77–79 by Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus , better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian...

. It is one of the largest single works to have survived from the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

to the modern day and purports to cover the entire field of ancient knowledge, based on the best authorities available to Pliny. He claims to be the only Roman ever to have undertaken such a work and prays for the blessing of the universal mother:

Hail to thee, Nature, thou parent of all things! and do thou deign to show thy favour unto me, who, alone of all the citizens of Rome, have, in thy every department, thus made known thy praise.The work became a model for all later encyclopedias in terms of the breadth of subject matter examined, the need to reference original authors, and a comprehensive index

Index (publishing)

An index is a list of words or phrases and associated pointers to where useful material relating to that heading can be found in a document...

list of the contents. The work is dedicated to the emperor Titus

Titus

Titus , was Roman Emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, thus becoming the first Roman Emperor to come to the throne after his own father....

, son of Pliny's close friend, the emperor Vespasian

Vespasian

Vespasian , was Roman Emperor from 69 AD to 79 AD. Vespasian was the founder of the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for a quarter century. Vespasian was descended from a family of equestrians, who rose into the senatorial rank under the Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty...

, in the first year of Titus's reign. It is the only work by Pliny to have survived and the last that he published, lacking a final revision at his sudden and unexpected death in the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius.

Table of contents

The Natural History consists of 37 books. Pliny devised his own table of contents. The table below is a summary based on modern names for topics.| I | Preface and tables of contents, lists of authorities |

| II | Mathematical and physical description of the world |

| III–VI | Geography Geography Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes... and ethnography Ethnography Ethnography is a qualitative method aimed to learn and understand cultural phenomena which reflect the knowledge and system of meanings guiding the life of a cultural group... |

| VII | Anthropology Anthropology Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German... and human physiology Physiology Physiology is the science of the function of living systems. This includes how organisms, organ systems, organs, cells, and bio-molecules carry out the chemical or physical functions that exist in a living system. The highest honor awarded in physiology is the Nobel Prize in Physiology or... |

| VIII–XI | Zoology Zoology Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct... |

| XII–XXVII | Botany Botany Botany, plant science, or plant biology is a branch of biology that involves the scientific study of plant life. Traditionally, botany also included the study of fungi, algae and viruses... , including agriculture Agriculture Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the... , horticulture Horticulture Horticulture is the industry and science of plant cultivation including the process of preparing soil for the planting of seeds, tubers, or cuttings. Horticulturists work and conduct research in the disciplines of plant propagation and cultivation, crop production, plant breeding and genetic... and pharmacology Pharmacology Pharmacology is the branch of medicine and biology concerned with the study of drug action. More specifically, it is the study of the interactions that occur between a living organism and chemicals that affect normal or abnormal biochemical function... |

| XXVIII–XXXII | Pharmacology Pharmacology Pharmacology is the branch of medicine and biology concerned with the study of drug action. More specifically, it is the study of the interactions that occur between a living organism and chemicals that affect normal or abnormal biochemical function... |

| XXXIII–XXXVII | Mining and mineralogy Mineralogy Mineralogy is the study of chemistry, crystal structure, and physical properties of minerals. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization.-History:Early writing... , especially in its application to life and art, including: gold Gold Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a... casting in silver Silver Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal... statuary Sculpture Sculpture is three-dimensional artwork created by shaping or combining hard materials—typically stone such as marble—or metal, glass, or wood. Softer materials can also be used, such as clay, textiles, plastics, polymers and softer metals... in bronze Bronze sculpture Bronze is the most popular metal for cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply a "bronze".Common bronze alloys have the unusual and desirable property of expanding slightly just before they set, thus filling the finest details of a mold. Then, as the bronze cools, it... painting Painting Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a surface . The application of the medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush but other objects can be used. In art, the term painting describes both the act and the result of the action. However, painting is... modelling sculpture in marble Marble sculpture Marble sculpture is the art of creating three-dimensional forms from marble. Sculpture is among the oldest of the arts. Even before painting cave walls, early humans fashioned shapes from stone. From these beginnings, artifacts have evolved to their current complexity... precious stones and gems |

Purpose

The scheme of his great work was vast and comprehensive, being nothing short of an encyclopediaEncyclopedia

An encyclopedia is a type of reference work, a compendium holding a summary of information from either all branches of knowledge or a particular branch of knowledge....

of learning and of art so far as they are connected with nature or draw their materials from nature. He admits that

- My subject is a barren one – the world of nature, or in other words life; and that subject in its least elevated department, and employing either rustic terms or foreign, nay barbarian words that actually have to be introduced with an apology. Moreover, the path is not a beaten highway of authorship, nor one in which the mind is eager to range: there is not one of us who has made the same venture, nor yet one Roman who has tackled single-handed all departments of the subject.

He admits the problems of writing such a work:

- It is a difficult task to give novelty to what is old, authority to what is new, brilliance to the common-place, light to the obscure, attraction to the stale, credibility to the doubtful, but nature to all things and all her properties to nature.

Sources

For this work, he studied the original authorities on each subject and was most assiduous in making excerpts from their pages. His indices auctorum are, in some cases, the authorities he had actually consulted (though they are not exhaustive); in other cases, they represent the principal writers on the subject, whose names are borrowed second-hand for his immediate authorities. He frankly acknowledges his obligations to all his predecessors in a phrase that deserves to be proverbial,plenum ingenni pudoris fateri per quos profeceris.

to own up to those who were the means of one's own achievementsAny criticism of his faults of omission is disarmed by the candour of the confession in his preface:

nec dubitamus multa esse quae et nos praeterierint; homines enim sumus et occupati officiis.

Nor do we doubt that many things have escaped us also; for we are but human, and beset with dutiesIn the preface, the author claims to have stated 20,000 facts gathered from some 2,000 books and from 100 select authors. The extant lists of his authorities amount to many more than 400, including 146 of Roman and 327 of Greek and other sources of information. The lists, as a general rule, follow the order of the subject matter of each book. This has been clearly shown in Heinrich Brunn

Heinrich Brunn

Heinrich Brunn was a German archaeologist.Brunn studied archaeology and philology in Bonn. In 1843 he received his doctorate degree with the work Artificum liberae Graeciae tempora and moved to Italy. He worked at the German Archaeological Institute in Rome until 1853...

's Disputatio (Bonn

Bonn

Bonn is the 19th largest city in Germany. Located in the Cologne/Bonn Region, about 25 kilometres south of Cologne on the river Rhine in the State of North Rhine-Westphalia, it was the capital of West Germany from 1949 to 1990 and the official seat of government of united Germany from 1990 to 1999....

, 1856).

Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro was an ancient Roman scholar and writer. He is sometimes called Varro Reatinus to distinguish him from his younger contemporary Varro Atacinus.-Biography:...

. In the geographical books, Varro is supplemented by the topographical commentaries of Agrippa, which were completed by the emperor Augustus

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

; for his zoology

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

, he relies largely on Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

and on Juba

Juba II

Juba II or Juba II of Numidia was a king of Numidia and then later moved to Mauretania. His first wife was Cleopatra Selene II, daughter to Greek Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and Roman triumvir Mark Antony.-Early life:Juba II was a prince of Berber descent from North Africa...

, the scholarly Mauretania

Mauretania

Mauretania is a part of the historical Ancient Libyan land in North Africa. It corresponds to present day Morocco and a part of western Algeria...

n king, studiorum claritate memorabilior quam regno (v. 16). Juba is one of his principal guides in botany; Theophrastus

Theophrastus

Theophrastus , a Greek native of Eresos in Lesbos, was the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He came to Athens at a young age, and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death he attached himself to Aristotle. Aristotle bequeathed to Theophrastus his writings, and...

is also named in his Indices, and since Theophrastus's botanical work survives, it is possible to see the extent to which Pliny uses him, translating (and occasionally mistranslating) Theophrastus's difficult Greek into Latin. Another work by Theophrastus, On Stones was a useful source of information on ores

Orés

Orés is a municipality in the Cinco Villas, in the province of Zaragoza, in the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It belongs to the comarca of Cinco Villas. It is placed 104 km to the northwest of the provincial capital city, Zaragoza. Its coordinates are: 42° 17' N, 1° 00' W, and is...

and minerals. He made use of all of the Greek histories available at the time, such as those of Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

and Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

, as well as the famous Bibliotheca historica

Bibliotheca historica

Bibliotheca historica , is a work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, and describe the history and culture of Egypt , of Mesopotamia, India, Scythia, and Arabia , of North...

of Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus was a Greek historian who flourished between 60 and 30 BC. According to Diodorus' own work, he was born at Agyrium in Sicily . With one exception, antiquity affords no further information about Diodorus' life and doings beyond what is to be found in his own work, Bibliotheca...

.

Working method

The following is a description of his methods of work on the natural historyNatural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

by his nephew, Pliny the Younger

Pliny the Younger

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo , better known as Pliny the Younger, was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and educate him...

:

Does it surprise you that a busy man found time to finish so many

volumes, many of which deal with such minute details? You will wonder

the more when I tell you that he for many years pleaded in the law

courts, that he died in his fifty-seventh year, and that in the interval

his time was taken up and his studies were hindered by the important

offices he held and the duties arising out of his friendship with the

Emperors. But he possessed a keen intellect; he had a marvellous

capacity for work, and his powers of application were enormous. He used

to begin to study at night on the Festival of Vulcan, not for luck but

from his love of study, long before dawn; in winter he would commence at

the seventh hour or at the eighth at the very latest, and often at the

sixth. He could sleep at call, and it would come upon him and leave him

in the middle of his work. Before daybreak he would go to Vespasian--

for he too was a night-worker—and then set about his official duties.

On his return home he would again give to study any time that he had

free. Often in summer after taking a meal, which with him, as in the

old days, was always a simple and light one, he would lie in the sun if

he had any time to spare, and a book would be read aloud, from which he

would take notes and extracts. For he never read without taking

extracts, and used to say that there never was a book so bad that it was

not good in some passage or another. After his sun bath he usually

bathed in cold water, then he took a snack and a brief nap, and

subsequently, as though another day had begun, he would study till

dinner-time. After dinner a book would be read aloud, and he would take

notes in a cursory way. I remember that one of his friends, when the

reader pronounced a word wrongly, checked him and made him read it

again, and my uncle said to him, "Did you not catch the meaning?" When

his friend said "yes," he remarked, "Why then did you make him turn

back? We have lost more than ten lines through your interruption." So

jealous was he of every moment lost.

Style

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca was a Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and in one work humorist, of the Silver Age of Latin literature. He was tutor and later advisor to emperor Nero...

. It aims less at clearness and vividness than at epigrammatic point. It abounds not only in antitheses, but also in questions and exclamations, tropes and metaphor

Metaphor

A metaphor is a literary figure of speech that uses an image, story or tangible thing to represent a less tangible thing or some intangible quality or idea; e.g., "Her eyes were glistening jewels." Metaphor may also be used for any rhetorical figures of speech that achieve their effects via...

s, and other mannerism

Mannerism

Mannerism is a period of European art that emerged from the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520. It lasted until about 1580 in Italy, when a more Baroque style began to replace it, but Northern Mannerism continued into the early 17th century throughout much of Europe...

s of the Silver Age. The rhythmical and artistic form of the sentence is sacrificed to a passion for emphasis that delights in deferring the point to the close of the period. The structure of the sentence is also apt to be loose and straggling. There is an excessive use of the ablative absolute, and ablative phrases are often appended in a kind of vague "apposition" to express the author's own opinion of an immediately previous statement, e.g.,

dixit (Apelles) … uno se praestare, quod manum de tabula sciret tollere, memorabili praecepto nocere saepe nimiam diligentiam.First publication

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus , better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian...

apparently published the first ten books himself in 77 and was engaged on revising and enlarging the rest during the two remaining years of his life. The work was probably published with little, if any, revision by the author's nephew Pliny the Younger

Pliny the Younger

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo , better known as Pliny the Younger, was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and educate him...

, who, when telling the story of a tame dolphin

Dolphin

Dolphins are marine mammals that are closely related to whales and porpoises. There are almost forty species of dolphin in 17 genera. They vary in size from and , up to and . They are found worldwide, mostly in the shallower seas of the continental shelves, and are carnivores, mostly eating...

and describing the floating islands of the Vadimonian Lake, thirty years later, has apparently forgotten that both are to be found in his uncle's work. He describes the Naturalis historia as a Naturae historia and characterizes it as a "work that is learned and full of matter, and as varied as nature herself."

The probable absence of the author's final revision may partly account for many repetitions, for some contradictions, for mistakes in passages borrowed from Greek

Greeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

authors, and for the insertion of marginal additions at wrong places in the text. Alternatively (or in addition), the work has been transcribed many times, and the chances of poor copying can only have increased as copies multiplied.

Manuscripts

Medicina Plinii

The Medicina Plinii or Medical Pliny is an anonymous Latin compilation of medical remedies dating to the early 4th century AD. The excerptor, saying that he speaks from experience, offers the work as a compact resource for travelers in dealing with hucksters who sell worthless drugs at exorbitant...

. Early in the 8th century, we find Bede

Bede

Bede , also referred to as Saint Bede or the Venerable Bede , was a monk at the Northumbrian monastery of Saint Peter at Monkwearmouth, today part of Sunderland, England, and of its companion monastery, Saint Paul's, in modern Jarrow , both in the Kingdom of Northumbria...

in possession of an excellent manuscript of parts of the work. Bede used the work in his own book "De Rerum Natura", especially the sections on meteorology

Meteorology

Meteorology is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the atmosphere. Studies in the field stretch back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not occur until the 18th century. The 19th century saw breakthroughs occur after observing networks developed across several countries...

and gems

Gemstone

A gemstone or gem is a piece of mineral, which, in cut and polished form, is used to make jewelry or other adornments...

. However, he updated and corrected Pliny on the tides.

In the 9th century, Alcuin

Alcuin

Alcuin of York or Ealhwine, nicknamed Albinus or Flaccus was an English scholar, ecclesiastic, poet and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student of Archbishop Ecgbert at York...

sends to Charlemagne

Charlemagne

Charlemagne was King of the Franks from 768 and Emperor of the Romans from 800 to his death in 814. He expanded the Frankish kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of Western and Central Europe. During his reign, he conquered Italy and was crowned by Pope Leo III on 25 December 800...

for a copy of the earlier books; and Dicuil

Dicuil

Dicuil, Irish monk and geographer, born in the second half of the 8th century.-Background:The exact dates of Dicuil's birth and death unknown...

gathers extracts from the pages of Pliny for his own Mensura orbis terrae (ca. 825).

Pliny's work was held in high esteem in the Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

. The number of extant manuscripts is about 200; but the best of the more ancient manuscripts, that at Bamberg

Bamberg

Bamberg is a city in Bavaria, Germany. It is located in Upper Franconia on the river Regnitz, close to its confluence with the river Main. Bamberg is one of the few cities in Germany that was not destroyed by World War II bombings because of a nearby Artillery Factory that prevented planes from...

, contains only books xxxii–xxxvii. Robert of Cricklade, prior

Prior

Prior is an ecclesiastical title, derived from the Latin adjective for 'earlier, first', with several notable uses.-Monastic superiors:A Prior is a monastic superior, usually lower in rank than an Abbot. In the Rule of St...

of St. Frideswide's Priory at Oxford

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

, dedicated to Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

a Defloratio consisting of nine books of selections taken from one of the manuscripts of this class, which has been recently recognized as sometimes supplying us with the only evidence for the true text. Among the later manuscripts, the codex Vesontinus, formerly at Besançon

Besançon

Besançon , is the capital and principal city of the Franche-Comté region in eastern France. It had a population of about 237,000 inhabitants in the metropolitan area in 2008...

(11th century), has been divided into three portions, now in Rome, Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, and Leiden respectively, while there is also a transcript of the whole of this manuscript at Leiden.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the multiplicity of texts in circulation, many were in a poor state. Thus, when Petrarch

Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca , known in English as Petrarch, was an Italian scholar, poet and one of the earliest humanists. Petrarch is often called the "Father of Humanism"...

bought a copy in Mantua

Mantua

Mantua is a city and comune in Lombardy, Italy and capital of the province of the same name. Mantua's historic power and influence under the Gonzaga family, made it one of the main artistic, cultural and notably musical hubs of Northern Italy and the country as a whole...

in 1350, he wrote:

- What would Cicero, or Livy, or the other great men of the past, Pliny above all, think if they could return to life and read their own works?

He answered his own rhetorical question that they would scarcely recognise them, owing to corruptions and errors that had over the years built up in the texts, an inevitable result of multiple hand copying. Petrarch went on to correct some of the most barbarous texts, but translation was difficult owing to the way Pliny, for example, introduced non-Latin words or described techniques long since lost or forgotten.

Printed copies

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

in 1469 by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer

Johann and Wendelin of Speyer

The brothers Johann and Wendelin of Speyer were German printers in Venice from 1468 to 1477....

, but the text was, in the words of J. F. Healy, "distinctly imperfect". The next important edition is Philemon Holland

Philemon Holland

Philemon Holland was an English translator.His father, John Holland, was a clergyman who fled the Kingdom of England during the persecutions of Mary I of England...

's much improved translation of 1601, and further versions multiplied as Pliny's reputation grew during the Renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

. It inspired many scholars to look again at the achievements of the classical world and the ways nature could be studied. It helped revive interest in minerals and mining

Mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

, for example, and Pliny is much quoted by Georg Agricola

Georg Agricola

Georgius Agricola was a German scholar and scientist. Known as "the father of mineralogy", he was born at Glauchau in Saxony. His real name was Georg Pawer; Agricola is the Latinised version of his name, Pawer meaning "farmer"...

in his magnum opus De Re Metallica

De re metallica

De re metallica is a book cataloguing the state of the art of mining, refining, and smelting metals, published in 1556. The author was Georg Bauer, whose pen name was the Latinized Georgius Agricola...

.

Sir Thomas Browne

Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne was an English author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including medicine, religion, science and the esoteric....

expressed a wholesome skepticism about Pliny's dependability in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica

Pseudodoxia Epidemica

Pseudodoxia Epidemica or Enquries into very many received tenets and commonly presumed truths, also known simply as Pseudodoxia Epidemica or Vulgar Errors, is a work by Thomas Browne refuting the common errors and superstitions of his age. It first appeared in 1646 and went through five subsequent...

(1646):

- "Now what is very strange, there is scarce a popular error passant in our days, which is not either directly expressed, or diductively contained in this Work; which being in the hands of most men, hath proved a powerful occasion of their propagation. Wherein notwithstanding the credulity of the Reader is more condemnable then the curiosity of the Author: for commonly he nameth the Authors from whom he received those accounts, and writes but as he reads, as in his Preface to Vespasian he acknowledgeth."

Highlights

The work divides neatly into the organic world of plants and animals and the realm of inorganic matter, although there are frequent digressions in each section. He is especially interested in not just describing the occurrence of plants and animals, but also their exploitation (or abuse) by man, especially Romans. The description of metalMetal

A metal , is an element, compound, or alloy that is a good conductor of both electricity and heat. Metals are usually malleable and shiny, that is they reflect most of incident light...

s and mineral

Mineral

A mineral is a naturally occurring solid chemical substance formed through biogeochemical processes, having characteristic chemical composition, highly ordered atomic structure, and specific physical properties. By comparison, a rock is an aggregate of minerals and/or mineraloids and does not...

s is particularly detailed and valuable for the history of science

History of science

The history of science is the study of the historical development of human understandings of the natural world and the domains of the social sciences....

as being the most extensive compilation still available from the ancient world.

Anthropology

He wrote that a menstruating woman who uncovers her body can scare away hailstorms, whirlwinds and lightning. Anything she touches turns sour including wine and meat. Seeds turn sterile, and plants wither. If she strips naked and walks around the field, caterpillars, worms and beetles fall off the ears of corn. Even when not menstruating, she can lull a storm out at sea by stripping.Botany

Papyrus

Papyrus is a thick paper-like material produced from the pith of the papyrus plant, Cyperus papyrus, a wetland sedge that was once abundant in the Nile Delta of Egypt....

and the various grades of papyrus available to Romans. Different types of trees and the properties of the wood from them receives a vigorous treatment. He describes the olive

Olive

The olive , Olea europaea), is a species of a small tree in the family Oleaceae, native to the coastal areas of the eastern Mediterranean Basin as well as northern Iran at the south end of the Caspian Sea.Its fruit, also called the olive, is of major agricultural importance in the...

tree in some detail, praising its virtues as one might expect. Botany

Botany

Botany, plant science, or plant biology is a branch of biology that involves the scientific study of plant life. Traditionally, botany also included the study of fungi, algae and viruses...

is well discussed by Pliny, using Theophrastus

Theophrastus

Theophrastus , a Greek native of Eresos in Lesbos, was the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He came to Athens at a young age, and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death he attached himself to Aristotle. Aristotle bequeathed to Theophrastus his writings, and...

as one of his sources.

Black pepper

Black pepper is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit, which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit, known as a peppercorn when dried, is approximately in diameter, dark red when fully mature, and, like all drupes, contains a single seed...

, ginger

Ginger

Ginger is the rhizome of the plant Zingiber officinale, consumed as a delicacy, medicine, or spice. It lends its name to its genus and family . Other notable members of this plant family are turmeric, cardamom, and galangal....

and cane sugar. The latter, rather surprisingly, is used only as a medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

. He mentions several different varieties of pepper, complaining of their cost, comparable with that of gold and silver.

Pliny is critical of luxury, but yet spends much time describing rare and expensive products popular with the rich and famous of Rome and is particularly scathing about perfume

Perfume

Perfume is a mixture of fragrant essential oils and/or aroma compounds, fixatives, and solvents used to give the human body, animals, objects, and living spaces "a pleasant scent"...

s:

- Perfumes are the most pointless of luxuries, for pearls and jewels are at least passed on the one's heirs, and clothes last for a time, but perfumes lose their fragrance and perish as soon as they are used.

He does give a summary of their ingredients, such as attar of roses, which he says is the most widely used base. Other substances added are myrrh

Myrrh

Myrrh is the aromatic oleoresin of a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus Commiphora, which grow in dry, stony soil. An oleoresin is a natural blend of an essential oil and a resin. Myrrh resin is a natural gum....

, cinnamon

Cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several trees from the genus Cinnamomum that is used in both sweet and savoury foods...

, and balsam

Amyris

Amyris is a genus of flowering plants in the citrus family, Rutaceae. The generic name is derived from the Greek word αμυρων , which means "intensely scented" and refers to the strong odor of the resin...

gum, to mention but a few.

Zoology

In zoologyZoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

, he mentions the different kinds of purple

Purple

Purple is a range of hues of color occurring between red and blue, and is classified as a secondary color as the colors are required to create the shade....

dye, especially the murex

Murex

Murex is a genus of medium to large sized predatory tropical sea snails. These are carnivorous marine gastropod molluscs in the family Muricidae, commonly calle "murexes" or "rock snails"...

snail, which was the highly prized source of Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple , also known as royal purple, imperial purple or imperial dye, is a purple-red natural dye, which is extracted from sea snails, and which was possibly first produced by the ancient Phoenicians...

. He describes the elephant

Elephant

Elephants are large land mammals in two extant genera of the family Elephantidae: Elephas and Loxodonta, with the third genus Mammuthus extinct...

and hippopotamus

Hippopotamus

The hippopotamus , or hippo, from the ancient Greek for "river horse" , is a large, mostly herbivorous mammal in sub-Saharan Africa, and one of only two extant species in the family Hippopotamidae After the elephant and rhinoceros, the hippopotamus is the third largest land mammal and the heaviest...

in detail, as well as the value and origin of the pearl

Pearl

A pearl is a hard object produced within the soft tissue of a living shelled mollusk. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is made up of calcium carbonate in minute crystalline form, which has been deposited in concentric layers. The ideal pearl is perfectly round and smooth, but many other...

and the invention of fish farming

Fish farming

Fish farming is the principal form of aquaculture, while other methods may fall under mariculture. Fish farming involves raising fish commercially in tanks or enclosures, usually for food. A facility that releases young fish into the wild for recreational fishing or to supplement a species'...

and oyster farming

Oyster farming

Oyster farming is an aquaculture practice in which oysters are raised for human consumption. Oyster farming most likely developed in tandem with pearl farming, a similar practice in which oysters are farmed for the purpose of developing pearls...

. Aquaria

Aquarium

An aquarium is a vivarium consisting of at least one transparent side in which water-dwelling plants or animals are kept. Fishkeepers use aquaria to keep fish, invertebrates, amphibians, marine mammals, turtles, and aquatic plants...

were popular pastimes of the rich, and Pliny provides several amusing anecdotes of the problems of owners becoming too closely attached to their fishes.

_(yvan_leduc_author_for_wikipedia).jpg)

Amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin , which has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Amber is used as an ingredient in perfumes, as a healing agent in folk medicine, and as jewelry. There are five classes of amber, defined on the basis of their chemical constituents...

is especially incisive, and he correctly identifies the source as being the fossilised resin

Resin

Resin in the most specific use of the term is a hydrocarbon secretion of many plants, particularly coniferous trees. Resins are valued for their chemical properties and associated uses, such as the production of varnishes, adhesives, and food glazing agents; as an important source of raw materials...

of pine trees. One piece of evidence is that some samples exhibit encapsulated insects, a feature that is readily explained if the original material is a viscous resin. He refers to the way in which it will exert a charge when rubbed, a property well known to Theophrastus

Theophrastus

Theophrastus , a Greek native of Eresos in Lesbos, was the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He came to Athens at a young age, and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death he attached himself to Aristotle. Aristotle bequeathed to Theophrastus his writings, and...

. Pliny devotes considerable space to bees, which he admires for their industry and organisation, and of course their honey

Honey

Honey is a sweet food made by bees using nectar from flowers. The variety produced by honey bees is the one most commonly referred to and is the type of honey collected by beekeepers and consumed by humans...

. Pliny relies on many previous authors and describes the use of smoke by beekeepers at the hive to collect the honeycomb

Honeycomb

A honeycomb is a mass of hexagonal waxcells built by honey bees in their nests to contain their larvae and stores of honey and pollen.Beekeepers may remove the entire honeycomb to harvest honey...

s. He also discusses the queen bee

Queen bee

The term queen bee is typically used to refer to an adult, mated female that lives in a honey bee colony or hive; she is usually the mother of most, if not all, the bees in the hive. The queens are developed from larvae selected by worker bees and specially fed in order to become sexually mature...

and her crucial role in the swarm.

His description of the song of the nightingale

Nightingale

The Nightingale , also known as Rufous and Common Nightingale, is a small passerine bird that was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family Turdidae, but is now more generally considered to be an Old World flycatcher, Muscicapidae...

is an elaborate example of his occasional felicity of phrase.

Metallurgy

Metal

A metal , is an element, compound, or alloy that is a good conductor of both electricity and heat. Metals are usually malleable and shiny, that is they reflect most of incident light...

s including gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

, silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

, copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

, mercury

Mercury (element)

Mercury is a chemical element with the symbol Hg and atomic number 80. It is also known as quicksilver or hydrargyrum...

, lead

Lead

Lead is a main-group element in the carbon group with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. Lead is a soft, malleable poor metal. It is also counted as one of the heavy metals. Metallic lead has a bluish-white color after being freshly cut, but it soon tarnishes to a dull grayish color when exposed...

, tin

Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a main group metal in group 14 of the periodic table. Tin shows chemical similarity to both neighboring group 14 elements, germanium and lead and has two possible oxidation states, +2 and the slightly more stable +4...

and iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

, as well as their many alloys such as electrum

Electrum

Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, with trace amounts of copper and other metals. It has also been produced artificially. The ancient Greeks called it 'gold' or 'white gold', as opposed to 'refined gold'. Its color ranges from pale to bright yellow, depending on the...

, bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

, pewter

Pewter

Pewter is a malleable metal alloy, traditionally 85–99% tin, with the remainder consisting of copper, antimony, bismuth and lead. Copper and antimony act as hardeners while lead is common in the lower grades of pewter, which have a bluish tint. It has a low melting point, around 170–230 °C ,...

, and steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

. He devotes much space to a long discussion about the greed for gold, such as the absurdity of using the metal for coins in the early Republic. He gives several examples of the way rulers proclaimed their prowess by exhibiting gold loot from their campaigns, such as that by Claudius

Claudius

Claudius , was Roman Emperor from 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was the son of Drusus and Antonia Minor. He was born at Lugdunum in Gaul and was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside Italy...

after conquering Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

, as well as relating the stories of Midas

Midas

For the legend of Gordias, a person who was taken by the people and made King, in obedience to the command of the oracle, see Gordias.Midas or King Midas is popularly remembered in Greek mythology for his ability to turn everything he touched into gold. This was called the Golden touch, or the...

and Croesus

Croesus

Croesus was the king of Lydia from 560 to 547 BC until his defeat by the Persians. The fall of Croesus made a profound impact on the Hellenes, providing a fixed point in their calendar. "By the fifth century at least," J.A.S...

. He then proceeds to discuss why the metal is unique in its malleability and ductility

Ductility

In materials science, ductility is a solid material's ability to deform under tensile stress; this is often characterized by the material's ability to be stretched into a wire. Malleability, a similar property, is a material's ability to deform under compressive stress; this is often characterized...

being far greater than any other metal. The examples given are its capability of being beaten into fine foil

Foil

Foil may refer to:Materials* Foil , a quite thin sheet of metal, usually manufactured with a rolling mill machine* Metal leaf, a very thin sheet of decorative metal* Aluminium foil, a type of wrapping for food...

with just one ounce, producing 750 leaves four inches square. Fine gold wire

Wire

A wire is a single, usually cylindrical, flexible strand or rod of metal. Wires are used to bear mechanical loads and to carry electricity and telecommunications signals. Wire is commonly formed by drawing the metal through a hole in a die or draw plate. Standard sizes are determined by various...

can be woven into cloth, although imperial clothes usually combined it with natural fibres like wool. He once saw Agrippina the Younger

Agrippina the Younger

Julia Agrippina, most commonly referred to as Agrippina Minor or Agrippina the Younger, and after 50 known as Julia Augusta Agrippina was a Roman Empress and one of the more prominent women in the Julio-Claudian dynasty...

, wife of Claudius

Claudius

Claudius , was Roman Emperor from 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was the son of Drusus and Antonia Minor. He was born at Lugdunum in Gaul and was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside Italy...

, at a public show on the Fucine Lake

Fucine Lake

The Fucine Lake was a large lake in central Italy, stretching from Avezzano in the northwest to Ortuccio in the southeast, and touching Trasacco in the southwest. It was drained in 1875.-Roman drainage:...

involving a naval battle, wearing a military cloak made of gold.

Given gold's value and importance to the Romans, its occurrence and extraction receives a long section of text and starts with a rejection of the ideas initiated by Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

of Indian gold obtained by ants or dug up by griffin

Griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon is a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle...

s in Scythia

Scythia

In antiquity, Scythian or Scyths were terms used by the Greeks to refer to certain Iranian groups of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who dwelt on the Pontic-Caspian steppe...

. The section is discussed in more detail below.

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

comes next in Pliny's pantheon of greed. It does not occur in native form and has to be mined, usually occurring with lead

Lead

Lead is a main-group element in the carbon group with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. Lead is a soft, malleable poor metal. It is also counted as one of the heavy metals. Metallic lead has a bluish-white color after being freshly cut, but it soon tarnishes to a dull grayish color when exposed...

ores. Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

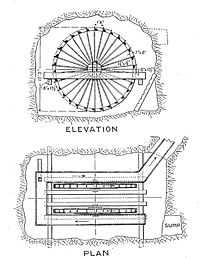

produced the most silver in his time, many of the mines having been started by Hannibal. One of the largest had galleries running for between one and two miles into the mountain, "water-men" (which he calls "aquatini") draining the mine, and they

- stood night and day in shifts measured by lamps, bailing out water and making a stream.

Pliny is probably referring to the reverse overshot water-wheel

Reverse overshot water-wheel

Frequently used in mines and probably elsewhere , the reverse overshot water wheel was a Roman innovation to help remove water from the lowest levels of underground workings. It is described by Vitruvius in his work De Architectura published circa 25 BC...

s operated by treadmill and found in Roman mines in the 1920s as discussed below. Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

, he says, is very rich in lead, which is found on the surface at many places, and thus very easy to extract; production was so high that a law was passed attempting to restrict mining.

Fraud

In criminal law, a fraud is an intentional deception made for personal gain or to damage another individual; the related adjective is fraudulent. The specific legal definition varies by legal jurisdiction. Fraud is a crime, and also a civil law violation...

and forgery

Forgery

Forgery is the process of making, adapting, or imitating objects, statistics, or documents with the intent to deceive. Copies, studio replicas, and reproductions are not considered forgeries, though they may later become forgeries through knowing and willful misrepresentations. Forging money or...

, and in particular coin counterfeiting

Coin counterfeiting

Coin counterfeiting of valuable antique coins is common; modern high-value coins are also counterfeited and circulated.Counterfeit antique coins are generally made to a very high standard so that they can deceive experts; this is not easy and many coins still stand out.-Circulating...

by mixing copper with silver, or even admixture with iron. Tests had been developed for counterfeit coins and proved very popular with the victims, mostly ordinary people.

In the same section, he deals with the liquid metal mercury

Mercury (element)

Mercury is a chemical element with the symbol Hg and atomic number 80. It is also known as quicksilver or hydrargyrum...

, which is also found in silver mines. He correctly says it is toxic, and amalgamates

Amalgam (chemistry)

An amalgam is a substance formed by the reaction of mercury with another metal. Almost all metals can form amalgams with mercury, notable exceptions being iron and platinum. Silver-mercury amalgams are important in dentistry, and gold-mercury amalgam is used in the extraction of gold from ore.The...

with gold, so is used for refining and extraction of that metal. He says mercury is used for gilding

Gilding

The term gilding covers a number of decorative techniques for applying fine gold leaf or powder to solid surfaces such as wood, stone, or metal to give a thin coating of gold. A gilded object is described as "gilt"...

copper. Antimony

Antimony

Antimony is a toxic chemical element with the symbol Sb and an atomic number of 51. A lustrous grey metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite...

is found in silver mines and is used as an eyebrow

Eyebrow

The eyebrow is an area of thick, delicate hairs above the eye that follows the shape of the lower margin of the brow ridges of some mammals. Their main function is to prevent sweat, water, and other debris from falling down into the eye socket, but they are also important to human communication and...

cosmetic

Cosmetics

Cosmetics are substances used to enhance the appearance or odor of the human body. Cosmetics include skin-care creams, lotions, powders, perfumes, lipsticks, fingernail and toe nail polish, eye and facial makeup, towelettes, permanent waves, colored contact lenses, hair colors, hair sprays and...

.

Cinnabar

Cinnabar or cinnabarite , is the common ore of mercury.-Word origin:The name comes from κινναβαρι , a Greek word most likely applied by Theophrastus to several distinct substances...

, long used as a pigment by painters. He says that the colour is similar to that of the cochineal

Cochineal

The cochineal is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the crimson-colour dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessile parasite native to tropical and subtropical South America and Mexico, this insect lives on cacti from the genus Opuntia, feeding on plant moisture and...

insect. The dust is very toxic, so workers handling the material wear face masks of bladder skin. Copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

and bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

are, says Pliny, most famous for their use in statues, of which there were many in Rome. Their most extravagant use was in colossi

Statue

A statue is a sculpture in the round representing a person or persons, an animal, an idea or an event, normally full-length, as opposed to a bust, and at least close to life-size, or larger...

, gigantic statues as tall as towers, the most famous being the Colossus of Rhodes

Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes was a statue of the Greek Titan Helios, erected in the city of Rhodes on the Greek island of Rhodes by Chares of Lindos between 292 and 280 BC. It is considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was constructed to celebrate Rhodes' victory over the ruler of...

. He personally saw the massive statue of Nero

Nero

Nero , was Roman Emperor from 54 to 68, and the last in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Nero was adopted by his great-uncle Claudius to become his heir and successor, and succeeded to the throne in 54 following Claudius' death....

in Rome, which was later removed after the emperor committed suicide. The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero's, death during Vespasian

Vespasian

Vespasian , was Roman Emperor from 69 AD to 79 AD. Vespasian was the founder of the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for a quarter century. Vespasian was descended from a family of equestrians, who rose into the senatorial rank under the Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty...

's reign, to make it truly a statue of Sol. Hadrian

Hadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheater. This building took the name Colosseum

Colosseum

The Colosseum, or the Coliseum, originally the Flavian Amphitheatre , is an elliptical amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, the largest ever built in the Roman Empire...

in the Middle Ages, after the statue nearby.

He gives a special place to iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

, distinguishing the hardness of steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

from what we now call wrought iron

Wrought iron

thumb|The [[Eiffel tower]] is constructed from [[puddle iron]], a form of wrought ironWrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon...

, a softer grade with (we know now) a smaller carbon

Carbon

Carbon is the chemical element with symbol C and atomic number 6. As a member of group 14 on the periodic table, it is nonmetallic and tetravalent—making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds...

content. He is scathing about the use of iron:

- and yet in other places we dig with sheer recklessness when iron is needed – a metal even more welcome than gold amid the bloodshed of war.

Mineralogy

Mineral

A mineral is a naturally occurring solid chemical substance formed through biogeochemical processes, having characteristic chemical composition, highly ordered atomic structure, and specific physical properties. By comparison, a rock is an aggregate of minerals and/or mineraloids and does not...

s and gemstone

Gemstone

A gemstone or gem is a piece of mineral, which, in cut and polished form, is used to make jewelry or other adornments...

s, building on works by Theophrastus

Theophrastus

Theophrastus , a Greek native of Eresos in Lesbos, was the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He came to Athens at a young age, and initially studied in Plato's school. After Plato's death he attached himself to Aristotle. Aristotle bequeathed to Theophrastus his writings, and...

and other authors. The topic concentrates on the most valuable gemstone

Gemstone

A gemstone or gem is a piece of mineral, which, in cut and polished form, is used to make jewelry or other adornments...

s, because it gives him yet another opportunity to criticize the obsession with luxury products such as engraved gems and hardstone carving

Hardstone carving

Hardstone carving is a general term in art history and archaeology for the carving for artistic purposes of semi-precious stones, also known as gemstones, such as jade, rock crystal , agate, onyx, jasper, serpentine or carnelian, and for an object made in this way. Normally the objects are small,...

s.

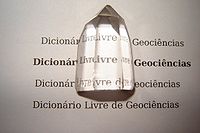

He accurately describes the octahedral shape of the diamond

Diamond

In mineralogy, diamond is an allotrope of carbon, where the carbon atoms are arranged in a variation of the face-centered cubic crystal structure called a diamond lattice. Diamond is less stable than graphite, but the conversion rate from diamond to graphite is negligible at ambient conditions...

and proceeds to mention that diamond dust is used by gem engravers to cut and polish other gems owing to its great hardness. His recognition of the importance of crystal

Crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are arranged in an orderly repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions. The scientific study of crystals and crystal formation is known as crystallography...

shape is a precursor to modern crystallography

Crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of the arrangement of atoms in solids. The word "crystallography" derives from the Greek words crystallon = cold drop / frozen drop, with its meaning extending to all solids with some degree of transparency, and grapho = write.Before the development of...

, while mention of numerous other minerals presages mineralogy

Mineralogy

Mineralogy is the study of chemistry, crystal structure, and physical properties of minerals. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization.-History:Early writing...

. He also recognises that other minerals have characteristic crystal shapes, but in one example, confuses the crystal habit

Crystal habit

Crystal habit is an overall description of the visible external shape of a mineral. This description can apply to an individual crystal or an assembly of crystals or aggregates....

with the work of lapidaries.

Nero

Nero

Nero , was Roman Emperor from 54 to 68, and the last in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Nero was adopted by his great-uncle Claudius to become his heir and successor, and succeeded to the throne in 54 following Claudius' death....

deliberately broke two crystal cups when he realised that he was about to be deposed, so denying anyone else of their use.

Pliny returns to the problem of fraud and the detection of false gems using several tests, including the scratch test, where counterfeit gems can be marked by a steel file, and genuine ones not. Perhaps it refers to glass imitations of jewellery

Jewellery

Jewellery or jewelry is a form of personal adornment, such as brooches, rings, necklaces, earrings, and bracelets.With some exceptions, such as medical alert bracelets or military dog tags, jewellery normally differs from other items of personal adornment in that it has no other purpose than to...

gemstones

Gemstones

Gemstones is the third solo album by Adam Green, released in 2005. The album is characterised by the heavy presence of Wurlitzer piano, whereas its predecessor relied on a string section in its instrumentation.-Track listing:#Gemstones – 2:24...

. He refers to using one hard mineral to scratch another, the first allusion to what is now the Mohs hardness scale. Diamond

Diamond

In mineralogy, diamond is an allotrope of carbon, where the carbon atoms are arranged in a variation of the face-centered cubic crystal structure called a diamond lattice. Diamond is less stable than graphite, but the conversion rate from diamond to graphite is negligible at ambient conditions...

sits at the top of the series because, Pliny says, it will scratch all other minerals.

Agriculture

Cato the Elder

Marcus Porcius Cato was a Roman statesman, commonly referred to as Censorius , Sapiens , Priscus , or Major, Cato the Elder, or Cato the Censor, to distinguish him from his great-grandson, Cato the Younger.He came of an ancient Plebeian family who all were noted for some...

and his work De Agri Cultura

De Agri Cultura

De Agri Cultura , written by Cato the Elder, is the oldest surviving work of Latin prose. Alexander Hugh McDonald, in his article for the Oxford Classical Dictionary, dated this essay's composition to about 160 BC and noted that "for all of its lack of form, its details of old custom and...

, which he uses as a primary source. Pliny's work includes discussion of all known cultivated crops and vegetables, as well as herbs and remedies derived from them. It is also a source for some interesting devices and machines used in cultivation and processing the crops. For example, he describes a simple mechanical reaper

Reaper

A reaper is a person or machine that reaps crops at harvest, when they are ripe.-Hand reaping:Hand reaping is done by various means, including plucking the ears of grains directly by hand, cutting the grain stalks with a sickle, cutting them with a scythe, or with a later type of scythe called a...

that cut the ears of wheat

Wheat

Wheat is a cereal grain, originally from the Levant region of the Near East, but now cultivated worldwide. In 2007 world production of wheat was 607 million tons, making it the third most-produced cereal after maize and rice...

and barley

Barley

Barley is a major cereal grain, a member of the grass family. It serves as a major animal fodder, as a base malt for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods...

without the straw and was pushed by oxen (Book XVIII, chapter 72). This device was forgotten in the Dark Ages, during which period reapers reverted to using scythe

Scythe

A scythe is an agricultural hand tool for mowing grass, or reaping crops. It was largely replaced by horse-drawn and then tractor machinery, but is still used in some areas of Europe and Asia. The Grim Reaper is often depicted carrying or wielding a scythe...

s and sickles to gather crops. It is depicted on a bas-relief from the later Roman period found at Trier

Trier

Trier, historically called in English Treves is a city in Germany on the banks of the Moselle. It is the oldest city in Germany, founded in or before 16 BC....

.

Watermills

The same book describes how the grain is ground using pestles powered by water wheelWater wheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of free-flowing or falling water into useful forms of power. A water wheel consists of a large wooden or metal wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving surface...

s, an important reference to a practice supported by the remains of many Roman water mills found across the Empire. The most impressive extant mills are found at Barbegal in southern France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, using water supplied by the aqueduct supplying Arles

Arles

Arles is a city and commune in the south of France, in the Bouches-du-Rhône department, of which it is a subprefecture, in the former province of Provence....

. The water powered no less than sixteen overshot water wheels arranged in two parallel sets of eight down the hillside.

It is thought that the wheels were overshot water wheels with the outflow from the top driving the next one down in the set, and so on to the base of the hill. Vertical water mills were well known to the Romans, being described by Vitruvius

Vitruvius

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio was a Roman writer, architect and engineer, active in the 1st century BC. He is best known as the author of the multi-volume work De Architectura ....

in his De Architectura

De architectura

' is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect Vitruvius and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide for building projects...

of 25 BC.

A sawmill

Sawmill

A sawmill is a facility where logs are cut into boards.-Sawmill process:A sawmill's basic operation is much like those of hundreds of years ago; a log enters on one end and dimensional lumber exits on the other end....

powered by a water wheel is known from another bas-relief from Hierapolis

Hierapolis

Hierapolis was the ancient Greco-Roman city which sat on top of hot springs located in south western Turkey near Denizli....

. Rather than using the direct drive from the rotating shaft, the Hierapolis sawmill

Hierapolis sawmill

The Hierapolis sawmill was a Roman water-powered stone sawmill at Hierapolis, Asia Minor . Dating to the second half of the 3rd century AD, the sawmill is the earliest known machine to combine a crank with a connecting rod....

powered a crankshaft

Crankshaft

The crankshaft, sometimes casually abbreviated to crank, is the part of an engine which translates reciprocating linear piston motion into rotation...

to activate the long saw blades in cutting stone. Part of the apparatus on the sarcophagus

Sarcophagus

A sarcophagus is a funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved or cut from stone. The word "sarcophagus" comes from the Greek σαρξ sarx meaning "flesh", and φαγειν phagein meaning "to eat", hence sarkophagus means "flesh-eating"; from the phrase lithos sarkophagos...

shows a gear train

Gear train

A gear train is formed by mounting gears on a frame so that the teeth of the gears engage. Gear teeth are designed to ensure the pitch circles of engaging gears roll on each other without slipping, this provides a smooth transmission of rotation from one gear to the next.The transmission of...

, so the speed of cutting could be increased or even controlled by appropriate choice of the gearing. Some partly cut stones have also been found at the site, confirming the method. The same technique could also have been used to cut timber.

There are later references to floating water mills from Byzantium

Byzantium

Byzantium was an ancient Greek city, founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 667 BC and named after their king Byzas . The name Byzantium is a Latinization of the original name Byzantion...

. The Aqua Traiana

Aqua Traiana

thumb|240px|Route of Aqua Traiana shown in red.thumb|240px|Route of Aqua Traiana within ancient Rome.The Aqua Traiana was a 1st-century Roman acqueduct built by Emperor Trajan and inaugurated on 24 June 109 AD...

fed water mills arranged in a parallel sequence at the Janiculum

Janiculum

The Janiculum is a hill in western Rome, Italy. Although the second-tallest hill in the contemporary city of Rome, the Janiculum does not figure among the proverbial Seven Hills of Rome, being west of the Tiber and outside the boundaries of the ancient city.-Sights:The Janiculum is one of the...

, under the present American Academy in Rome

American Academy in Rome

The American Academy in Rome is a research and arts institution located on the Gianicolo in Rome.- History :In 1893, a group of American architects, painters and sculptors met regularly while planning the fine arts section of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition...

. The milling complex had a long history and were famously put out of action by the Ostrogoths when they cut the aqueduct in 537 AD during the first siege of Rome. Belisarius

Belisarius

Flavius Belisarius was a general of the Byzantine Empire. He was instrumental to Emperor Justinian's ambitious project of reconquering much of the Mediterranean territory of the former Western Roman Empire, which had been lost less than a century previously....

restored the supply of grain by using mills floating in the Tiber. The complex of mills bear parallels with a similar complex at Barbegal in southern Gaul and to sawmill

Sawmill

A sawmill is a facility where logs are cut into boards.-Sawmill process:A sawmill's basic operation is much like those of hundreds of years ago; a log enters on one end and dimensional lumber exits on the other end....

s on the river Moselle

Moselle

Moselle is a department in the east of France named after the river Moselle.- History :Moselle is one of the original 83 departments created during the French Revolution on March 4, 1790...

by the poet Ausonius

Ausonius

Decimius Magnus Ausonius was a Latin poet and rhetorician, born at Burdigala .-Biography:Decimius Magnus Ausonius was born in Bordeaux in ca. 310. His father was a noted physician of Greek ancestry and his mother was descended on both sides from long-established aristocratic Gallo-Roman families...

. The use of multiple stacked sequences of reverse overshot water-wheel

Reverse overshot water-wheel

Frequently used in mines and probably elsewhere , the reverse overshot water wheel was a Roman innovation to help remove water from the lowest levels of underground workings. It is described by Vitruvius in his work De Architectura published circa 25 BC...

s was widespread in Roman mines.

Art history

In the history of art, the original Greek authorities are Duris of Samos

Duris of Samos

Duris of Samos ; probably born around 350 BC; died after 281 BC) was a Greek historian and was at some period tyrant of Samos.- Personal and political life :Duris claimed to be a descendant of Alcibiades, and was the brother of Lynceus of Samos...

, Xenocrates of Sicyon, and Antigonus of Carystus

Antigonus of Carystus

Antigonus of Carystus , Greek writer on various subjects, flourished in the 3rd century BC. After some time spent at Athens and in travelling, he was summoned to the court of Attalus I of Pergamum...

. The anecdotic element has been ascribed to Duris (xxxiv. 61, Lysippum Sicyonium Duris begat nullius fuisse discipulum etc.); the notices of the successive developments of art and the list of workers in bronze and painters to Xenocrates; and a large amount of miscellaneous information to Antigonus. The last two authorities are named in connection with Parrhasius

Zeuxis and Parrhasius

.Zeuxis was a painter who flourished during the 5th century BC.-Life and work:Zeuxis was born in Heraclea, probably Heraclea Lucania in southern Italy, around 464 BC and was presumably the pupil of Apollodorus. Zeuxis often thought himself misunderstood by his public and Aristotle did not like...

(xxxv. 68, hanc ei gloriam concessere Antigonus et Xenocrates, qui de pictura scripsere), while Antigonus is named in the indices of xxxiii – xxxiv as a writer on the "toreutic art", or the art of embossing metal, or working it in ornamental relief or intaglio

Intaglio

Intaglio are techniques in art in which an image is created by cutting, carving or engraving into a flat surface and may also refer to objects made using these techniques:* Intaglio , a group of printmaking techniques with an incised image...

.

Greek epigram

Epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, usually memorable and sometimes surprising statement. Derived from the epigramma "inscription" from ἐπιγράφειν epigraphein "to write on inscribe", this literary device has been employed for over two millennia....

s contribute their share in Pliny's descriptions of pictures and statues. One of the minor authorities for books xxxiv – xxxv is Heliodorus of Athens

Heliodorus of Athens

Heliodorus of Athens was an ancient author who wrote fifteen books on the Acropolis of Athens, possibly about 150 BC...

, the author of a work on the monuments of Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

. In the indices to xxxiii – xxxvi, an important place is assigned to Pasiteles

Pasiteles

Pasiteles was a Neo-Attic school sculptor from Ancient Rome at the time of Julius Caesar. Pasiteles is said by Pliny to have been a native of Magna Graecia, and to have been granted Roman citizenship...