Millbank Prison

Encyclopedia

Millbank

Millbank is an area of central London in the City of Westminster. Millbank is located by the River Thames, east of Pimlico and south of Westminster...

, Pimlico

Pimlico

Pimlico is a small area of central London in the City of Westminster. Like Belgravia, to which it was built as a southern extension, Pimlico is known for its grand garden squares and impressive Regency architecture....

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, originally constructed as the National Penitentiary, and which for part of its history served as a holding facility for convicted prisoners before they were transported to Australia

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

. It was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890.

Design and construction

The site at Millbank was originally purchased in 1799 on behalf of the Crown by the philosopher Jeremy BenthamJeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism...

, for the erection of his Panopticon

Panopticon

The Panopticon is a type of building designed by English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late eighteenth century. The concept of the design is to allow an observer to observe all inmates of an institution without them being able to tell whether or not they are being watched...

prison as Britain's new National Penitentiary. After various vicissitudes, the Panopticon plan was abandoned in 1812. An architectural competition was then held for a new Penitentiary design. It attracted 43 entrants, the winner being William Williams, drawing master at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

Royal Military Academy Sandhurst

The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst , commonly known simply as Sandhurst, is a British Army officer initial training centre located in Sandhurst, Berkshire, England...

. Williams' basic design was adapted by a practising architect, Thomas Hardwick

Thomas Hardwick

Thomas Hardwick was a British architect and a founding member of the Architect's Club in 1791.-Early life and career :Hardwick was born in Brentford, the son of a master mason turned architect also named Thomas Hardwick Thomas Hardwick (1752–1829) was a British architect and a founding...

, who began construction in the same year. Hardwick resigned in 1813, and John Harvey took over the role. Harvey was dismissed in turn in 1815, and replaced by Robert Smirke

Robert Smirke (architect)

Sir Robert Smirke was an English architect, one of the leaders of Greek Revival architecture his best known building in that style is the British Museum, though he also designed using other architectural styles...

, who brought the project to completion in 1821.

The marshy site on which the prison stood meant that the builders experienced problems of subsidence from the outset (and explains the succession of architects). Smirke finally resolved the difficulty by introducing a highly innovative concrete

Concrete

Concrete is a composite construction material, composed of cement and other cementitious materials such as fly ash and slag cement, aggregate , water and chemical admixtures.The word concrete comes from the Latin word...

raft to provide a secure foundation. However, this added considerably to the construction costs, which eventually totalled £500,000, more than twice the original estimate.

History

The first prisoners, all women, were admitted on 26 June 1816, the first men arriving in January 1817. The prison held 103 men and 109 women by the end of 1817, and 452 men and 326 women by late 1822. Sentences of five to ten years in the National Penitentiary were offered as an alternative to transportationPenal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

to those thought most likely to reform.

In addition to the problems of construction, the marshy site fostered disease, to which the prisoners had little immunity owing to their extremely poor diet. In 1822-3 an epidemic swept through the prison, which seems to have comprised a mixture of dysentery, scurvy, depression and other disorders. The decision was eventually taken to evacuate the buildings for several months: the female prisoners were released, and the male prisoners temporarily transferred to the prison hulks at Woolwich

Woolwich

Woolwich is a district in south London, England, located in the London Borough of Greenwich. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.Woolwich formed part of Kent until 1889 when the County of London was created...

(where their health improved).

The design also turned out to be unsatisfactory. The network of corridors was so labyrinthine that even the warders got lost; and the ventilation system allowed sound to carry, so that prisoners could communicate between cells. The annual running costs turned out to be an unsupportable £16,000.

In view of these problems, the decision was eventually taken to build a new 'model prison' at Pentonville

Pentonville (HM Prison)

HM Prison Pentonville is a Category B/C men's prison, operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not actually within Pentonville itself, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury area of the London Borough of Islington, in inner-North London,...

, which opened in 1842 and took over Millbank's role as the National Penitentiary. By an Act of Parliament of 1843, Millbank's status was downgraded, and it became a holding depot for convicts prior to transportation. Every person sentenced to transportation

Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

was sent to Millbank first, where they were held for three months before their final destination was decided. By 1850, around 4,000 people convicted of crimes were being transported annually from the UK. Prisoners awaiting transportation were kept in solitary confinement and restricted to silence for the first half of their sentence.

Large-scale transportation ended in 1853 (although the practice continued on a reduced scale until 1867); and Millbank then became an ordinary local prison, and from 1870 a military prison. It closed in 1890. Demolition began in 1892.

Description

In the Handbook of London in 1850 the prison was described as:

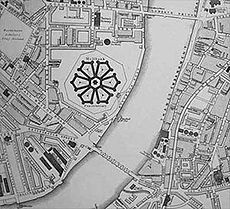

- MILLBANK PRISON. A mass of brickwork equal to a fortress, on the left bank of the Thames, close to Vauxhall BridgeVauxhall BridgeVauxhall Bridge is a Grade II* listed steel and granite deck arch bridge in central London. It crosses the River Thames in a south–east north–west direction between Vauxhall on the south bank and Pimlico on the north bank...

; erected on ground bought in 1799 of the Marquis of Salisbury, and established pursuant to 52 Geo. III., c.44, passed Aug 20th, 1812. It was designed by Jeremy Bentham [factually incorrect], to whom the fee-simple of the ground was conveyed, and is said to have cost the enormous sum of half a million sterling. The external walls form an irregular octagon, and enclose upwards of sixteen acres of land. Its ground-plan resembles a wheel, the governor's house occupying a circle in the centre, from which radiate six piles of building, terminating externally in towers. The ground on which it stands is raised but little above the river, and was at one time considered unhealthy. It was first named "The Penitentiary," or "Penitentiary House for London and Middlesex," and was called "The Millbank Prison" pursuant to 6 & 7 of Victoria, c.26. It is the largest prison in London. Every male and female convict sentenced to transportationPenal transportationTransportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

in Great Britain is sent to Millbank previous to the sentence being executed. Here they remain about three months under the close inspection of the three inspectors of the prison, at the end of which time the inspectors report to the Home Secretary, and recommend the place of transportation. The number of persons in Great Britain and Ireland condemned to transportation every year amounts to about 4000. So far the accommodation of the prison permits, the separate systemSeparate systemThe Separate system is a form of prison management based on the principle of keeping prisoners in solitary confinement. When first introduced in the early 19th century, the objective of such a prison or "penitentiary" was that of penance by the prisoners through silent reflection, as much as that...

is adopted. Admission to inspect - order from the Secretary for the Home Department, or the Inspector of Prisons.

Later development of the site

On the site of the prison was subsequently built the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate BritainTate Britain

Tate Britain is an art gallery situated on Millbank in London, and part of the Tate gallery network in Britain, with Tate Modern, Tate Liverpool and Tate St Ives. It is the oldest gallery in the network, opening in 1897. It houses a substantial collection of the works of J. M. W. Turner.-History:It...

), which opened in 1897; The Royal Army Medical School, the buildings of which were adapted in 2005 to become the Chelsea College of Art & Design; and - using the original bricks of the former prison - a housing estate constructed by the London County Council (LCC) between 1897 and 1902. Millbank Estate is now a TMO (tenant management organisation) and the 17 buildings, each named after one of Britain's best known painters, are Grade II listed.

Remains

A large circular bollardBollard

A bollard is a short vertical post. Originally it meant a post used on a ship or a quay, principally for mooring. The word now also describes a variety of structures to control or direct road traffic, such as posts arranged in a line to obstruct the passage of motor vehicles...

stands by the river with the inscription: "Near this site stood Millbank Prison which was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890. This buttress stood at the head of the river steps from which, until 1867, prisoners sentenced to transportation embarked on their journey to Australia."

Part of the perimeter ditch of the prison survives running between Cureton Street and John Islip Street: it is now used as a clothes-drying area for residents of Wilkie House.

The granite gate piers at the entrance of Purbeck House, High Street, Swanage

Swanage

Swanage is a coastal town and civil parish in the south east of Dorset, England. It is situated at the eastern end of the Isle of Purbeck, approximately 10 km south of Poole and 40 km east of Dorchester. The parish has a population of 10,124 . Nearby are Ballard Down and Old Harry Rocks,...

in Dorset, and a granite bollard next to the gate, are believed by English Heritage

English Heritage

English Heritage . is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport...

to be from Millbank prison.

Cultural references

In Henry JamesHenry James

Henry James, OM was an American-born writer, regarded as one of the key figures of 19th-century literary realism. He was the son of Henry James, Sr., a clergyman, and the brother of philosopher and psychologist William James and diarist Alice James....

's realist

Literary realism

Literary realism most often refers to the trend, beginning with certain works of nineteenth-century French literature and extending to late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century authors in various countries, towards depictions of contemporary life and society "as they were." In the spirit of...

novel The Princess Casamassima

The Princess Casamassima

The Princess Casamassima is a novel by Henry James, first published as a serial in The Atlantic Monthly in 1885-1886 and then as a book in 1886. It is the story of an intelligent but confused young London bookbinder, Hyacinth Robinson, who becomes involved in radical politics and a terrorist...

(1886) the prison is the 'primal scene' of Hyacinth Robinson's life: the visit to his mother, dying in the infirmary, is described in chapter 3. James visited Millbank on 12 December 1884

to gain material.

The prison is also evocatively described in Sarah Waters

Sarah Waters

Sarah Waters is a British novelist. She is best known for her novels set in Victorian society, such as Tipping the Velvet and Fingersmith.-Childhood:Sarah Waters was born in Neyland, Pembrokeshire, Wales in 1966....

' 1999 novel Affinity

Affinity (novel)

Affinity is a 1999 historical fiction novel by Sarah Waters. It is the author's second novel, following Tipping the Velvet, and followed by Fingersmith.-Plot summary:...

.

See also

- Convicts in AustraliaConvicts in AustraliaDuring the late 18th and 19th centuries, large numbers of convicts were transported to the various Australian penal colonies by the British government. One of the primary reasons for the British settlement of Australia was the establishment of a penal colony to alleviate pressure on their...

- Penal transportationPenal transportationTransportation or penal transportation is the deporting of convicted criminals to a penal colony. Examples include transportation by France to Devil's Island and by the UK to its colonies in the Americas, from the 1610s through the American Revolution in the 1770s, and then to Australia between...

- PanopticonPanopticonThe Panopticon is a type of building designed by English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late eighteenth century. The concept of the design is to allow an observer to observe all inmates of an institution without them being able to tell whether or not they are being watched...

- separate systemSeparate systemThe Separate system is a form of prison management based on the principle of keeping prisoners in solitary confinement. When first introduced in the early 19th century, the objective of such a prison or "penitentiary" was that of penance by the prisoners through silent reflection, as much as that...

External links

- Collection of Victorian references

- 1859 map - the penitentiary is the distinctive six-pointed building near the bottom

- Millbank Estate today