Lyndon LaRouche

Encyclopedia

Lyndon Hermyle LaRouche, Jr. (born September 8, 1922) is an American political activist and founder of a network of political committees, parties, and publications known collectively as the LaRouche movement

. Often described as a political extremist, he has written prolifically in his publications on economic, scientific, and political topics, as well as on history, philosophy, and psychoanalysis, largely promoting a conspiracist view of history and current affairs.

LaRouche was a perennial presidential candidate from 1976 to 2004, running once for his own U.S. Labor Party

and campaigning seven times for the Democratic Party

nomination, though he failed to attract appreciable electoral support. He was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment in 1988 for conspiracy to commit mail fraud and tax code violations, but continued his political activities from behind bars until his release in 1994 on parole. Ramsey Clark

, his chief appellate attorney and a former U.S. Attorney General, argued that LaRouche was denied a fair trial but the Court of Appeals unanimously rejected the appeal.

Members of the LaRouche movement see LaRouche as a political leader in the tradition of Franklin D. Roosevelt

. Other commentators, including The Washington Post and The New York Times, have described him over the years as a conspiracy theorist, fascist, and anti-Semite, and have characterized his movement as a cult. Norman Bailey

, formerly with the National Security Council

, described LaRouche's staff in 1984 as one of the best private intelligence services in the world, while the Heritage Foundation

, a conservative think tank, wrote that he leads "what may well be one of the strangest political groups in American history."

His parents became Quakers

after his father had converted from Roman Catholicism, and his mother from Protestantism. They forbade him from fighting with other children, even in self-defense, which he said led to "years of hell" from bullies at school. As a result, he spent much of his time alone, taking long walks through the woods and identifying in his mind with great philosophers. He wrote that, between the ages of twelve and fourteen, he read philosophy extensively, embracing the ideas of Leibniz

, and rejecting those of Hume

, Bacon

, Hobbes

, Locke

, Berkeley

, Rousseau

, and Kant

. He graduated from Lynn's English High School

in 1940. In the same year, the Lynn Quakers expelled his father from the group, for reportedly accusing other Quakers of misusing funds, while writing under the pen name Hezekiah Micajah Jones. LaRouche and his mother resigned in sympathy for his father.

(CO) during World War II, and joined a Civilian Public Service

camp, where, in the words of Dennis King, he "promptly joined a small faction at odds with the administrators." In 1944 he joined the United States Army as a non-combatant and served in India and Burma with medical units and ending the war as an ordnance clerk. He described his decision to serve as one of the most important of his life. While in India he developed sympathy for the Indian Independence movement

. LaRouche wrote that many GIs feared they would be asked to support British forces in actions against Indian independence forces, and that prospect was "revolting to most of us."

He discussed Marxism

in the CO camp, and while traveling home on the SS General Bradley in 1946, he met Don Merrill, a fellow soldier, also from Lynn, who converted him to Trotskyism

. Back in the U.S., he resumed his education at Northeastern University, but left because of his perception of academic "philistinism." He returned to Lynn in 1948, and the next year joined the Socialist Workers Party

(SWP), adopting the pseudonym Lyn Marcus for his political work. He arrived in New York City in 1953, where he took a job as a management consultant. In 1954 he married Janice Neuberger, a psychiatrist and member of the SWP. Their son, Daniel, was born in 1956.

, a faction which was later expelled from the SWP, and came under the influence of British Trotskyist leader Gerry Healy

. For six months, LaRouche worked with American Healyite leader Tim Wohlforth

, who later wrote that LaRouche had a "gargantuan ego," and "a marvelous ability to place any world happening in a larger context, which seemed to give the event additional meaning, but his thinking was schematic, lacking factual detail and depth."

In 1967 LaRouche began teaching classes on Marx's dialectical materialism

at New York City's Free School, and attracted a group of students from Columbia University and the City College of New York, recommending that they read Das Kapital

, as well as Hegel, Kant, and Leibniz. During the 1968 Columbia University protests

, he organized his supporters under the name the National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC). The aim of the NCLC was to win control of the Students for a Democratic Society

branch—the university's main activist group—and build a political alliance between students, local residents, organized labor, and the Columbia faculty. By 1973 the NCLC had over 600 members in 25 cities—including West Berlin and Stockholm—and produced what King called the most literate of the far-left papers, New Solidarity. The NCLC's internal activities became highly regimented over the next few years. Members gave up their jobs and devoted themselves to the group and its leader, believing it would soon take control of America's trade unions and overthrow the government.

, founded in 1974 and known for its conspiracy theories, including that Queen Elizabeth II is the head of an international drug-smuggling cartel, and that the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing

was part of a British attempt to take over the United States. Others included New Solidarity, Fusion Magazine, 21st Century Science and Technology, and Campaigner Magazine. His news services and publishers included American System Publications, Campaigner Publications, New Solidarity International Press Service, and The New Benjamin Franklin House Publishing Company. LaRouche acknowledged in 1980 that his followers impersonated reporters and others, saying it had to be done for his security. In 1982, U.S. News and World Report sued New Solidarity International Press Service and Campaigner Publications for damages, alleging that members were impersonating its reporters in phone calls.

U.S. sources told the Washington Post in 1985 that the LaRouche organization had assembled a worldwide network of government and military contacts, and that his researchers sometimes supplied information to government officials. Bobby Ray Inman

, the CIA's deputy director in 1981 and 1982, said LaRouche and his wife had visited him offering information about the West German Green Party, and a CIA spokesman said LaRouche met Deputy Director John McMahon in 1983 to discuss one of LaRouche's trips overseas. An aide to William Clark said when LaRouche's associates discussed technology or economics, they made good sense and seemed to be qualified. Norman Bailey, formerly with the National Security Council, said in 1984 that LaRouche's staff comprised "one of the best private intelligence services in the world"; he said, "They do know a lot of people around the world. They do get to talk to prime ministers and presidents." Several government officials feared a security leak from the government's ties with the movement.

According to critics, the supposed behind-the-scenes processes, were more often flights of fancy than inside information. Douglas Foster wrote in Mother Jones in 1982 that the briefings consisted of disinformation, "hate-filled" material about enemies, phony letters, intimidation, fake newspaper articles, and dirty tricks campaigns. Opponents were accused of being gay or Nazis, or were linked to murders, which the movement called "psywar techniques."

From the 1970s through to the 2000s, LaRouche founded several groups and companies. In addition to the National Caucus of Labor Committees, there was the Citizens Electoral Council

(Australia), the National Democratic Policy Committee, the Fusion Energy Foundation

, and the U.S. Labor Party. In 1984 he founded the Schiller Institute

in Germany with his second wife, and three political parties there—the Europäische Arbeiterpartei, Patrioten für Deutschland, and Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität

—and in 2000 the Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement

. His printing services included Computron Technologies, Computype, World Composition Services, and PMR Printing Company, Inc, or PMR Associates.

LaRouche wrote in his 1987 autobiography that violent altercations had begun in 1969 between his NCLC members and several New Left

LaRouche wrote in his 1987 autobiography that violent altercations had begun in 1969 between his NCLC members and several New Left

groups when Mark Rudd

's faction began assaulting LaRouche's faction at Columbia University. Press accounts alleged that between April and September 1973, during what LaRouche called "Operation Mop-Up," NCLC members began physically attacking members of leftist groups that LaRouche classified as "left-protofascists"; an editorial in LaRouche's New Solidarity said of the Communist Party that the movement "must dispose of this stinking corpse." Armed with chains, bats, and martial-art nunchuk sticks, they assaulted Communist Party, SWP, and Progressive Labor Party members and Black Power

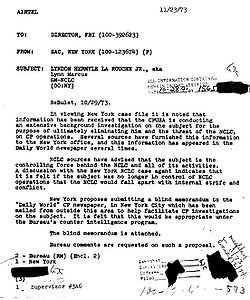

activists, on the streets and during meetings. At least 60 assaults were reported. The operation ended when police arrested several of LaRouche's followers; there were no convictions, and LaRouche maintained they had acted in self-defense. King writes that the FBI may have tried to aggravate the strife, using measures such as anonymous mailings, to keep the groups at each others' throats. LaRouche said he met representatives of the Soviet Union at the United Nations in 1974 and 1975 to discuss attacks by the Communist Party USA on the NCLC and to propose a merger, but said he received no assistance from them. One FBI memo, recovered under the Freedom of Information Act, proposes assisting the CPUSA in an investigation "for the purpose of ultimately eliminating him [LaRouche] and the threat of the NCLC." (see image to left)

LaRouche's critics such as Dennis King and Antony Lerman

allege that in 1973 and with little warning, LaRouche adopted more extreme ideas, a process accompanied by a campaign of violence against his opponents on the left, and the development of conspiracy theories and paranoia about his personal safety. According to these accounts, he began to believe he was under threat of assassination from the Soviet Union, the CIA, Libya, drug dealers, and bankers. Paul L. Montgomery

suggested in The New York Times that the change of political direction might have been linked to his partner, Carol Schnitzer/Larrabee, having left him in 1972 for a British activist, Chris White (see below). LaRouche apparently spent months in Germany, and returned with what Montgomery described as a "messianic vision." He spent most of his time in his bathrobe in his New York apartment, and began to suggest there was a conspiracy against him led by the Rockefeller family and the British. He also established a "Biological Holocaust Task Force," predicting that an epidemic of apocalyptic proportions would strike humanity in the 1980s.

LaRouche founded the U.S. Labor Party in 1973 as the political arm of the NCLC. The USLP is described in LaRouche's résumé as "an independent political association committed to the tradition of Benjamin Franklin

LaRouche founded the U.S. Labor Party in 1973 as the political arm of the NCLC. The USLP is described in LaRouche's résumé as "an independent political association committed to the tradition of Benjamin Franklin

, Alexander Hamilton

, Henry C. Carey

, and President Abraham Lincoln

." LaRouche describes it in another location as "a new Whig

association," adding that an important objective of the party was to fight against "the attempted revival of the 'preventive nuclear war' organization, the revived Committee on the Present Danger

."

A two-part article in The New York Times in 1979 by Howard Blum and Paul L. Montgomery alleged that LaRouche had turned it—at that point with 1,000 members in 37 offices in North America, and 26 in Europe and Latin America—into an extreme-right, anti-Semitic organization, despite the presence of Jewish members. LaRouche denied the newspaper's charges, and said he had filed a $100 million libel suit; his press secretary said the articles were intended to "set up a credible climate for an assassination hit." The Times alleged that members had taken courses in how to use knives and rifles; that a farm in upstate New York had been used for guerrilla training; and that several members had undergone a six-day anti-terrorist training course run by Mitchell WerBell III

, an arms dealer and former member of the Office of Strategic Services

, who said he had ties to the CIA

. Journalists and publications the party regarded as unfriendly were harassed, and it published a list of potential assassins it saw as a threat. LaRouche expected members to devote themselves entirely to the party, and place their savings and possessions at its disposal, as well as take out loans on its behalf. Party officials would decide who each member should live with, and if someone left the movement, his remaining partner was expected to live separately from him. LaRouche would question spouses about their partner's sexual habits, the Times said, and in one case reportedly ordered a member to stop having sex with his wife because it was making him "politically impotent."

He recorded sessions with a 26-year-old British member, Chris White, who had moved to England with LaRouche's former partner, Carol Schnitzer. In December 1973 LaRouche asked the couple to return to the U.S.; his followers sent tapes of the subsequent sessions with White to The New York Times as evidence of an assassination plot. According to the Times, "[t]here are sounds of weeping, and vomiting on the tapes, and Mr. White complains of being deprived of sleep, food and cigarettes. At one point someone says 'raise the voltage,' but (LaRouche) says this was associated with the bright lights used in the questioning rather than an electric shock." The Times wrote, "Mr. White complains of a terrible pain in his arm," then LaRouche can be heard saying, 'That's not real. That's in the program'." LaRouche told the newspaper White had been "reduced to an eight-cycle infinite loop with look-up table, with homosexual bestiality"; he said White had not been harmed and that a physician—a LaRouche movement member—had been present throughout. White ended up telling LaRouche he had been programmed by the CIA and British intelligence to set up LaRouche for assassination by Cuban frogmen.

According to The Washington Post, "brainwashing hysteria" took hold of the movement; one activist said he attended meetings where members were writhing on the floor saying they needed de-programming. In two weeks in January 1974, the group issued 41 separate press releases about brainwashing. One activist, Alice Weitzman, expressed skepticism about the claims. According to The New York Times, LaRouche sent six NCLC members to her apartment, where she was held captive for two days until she alerted a passer-by throwing a piece of paper out of her window asking for help. The members, who were charged with unlawful imprisonment, told police she had been brainwashed to help the KGB and needed deprogramming. Weitzman was reluctant to testify and the charges were dismissed.

and the Liberty Lobby

in 1974. Frank Donner

and Randall Rothenberg

wrote that he made successful overtures to the Liberty Lobby and George Wallace

's American Independent Party

, adding that the "racist" policies of LaRouche's U.S. Labor Party endeared it to members of the Ku Klux Klan. Gregory Rose, a former chief of counter-intelligence for LaRouche who became an FBI informant in 1973, said the contacts with the Liberty Lobby were extensive. George and Wilcox say that while the contact is often used to imply "'links' and 'ties' between LaRouche and the extreme right", it was in fact transient and marked by mutual suspicion. The Liberty Lobby pronounced itself disillusioned with LaRouche's views in 1981, because of what they described as his softness on "the major Zionist groups". According to George and Wilcox, American neo-Nazi leaders expressed suspicion over the number of Jews and members of other minority groups in his organization, and did not consider LaRouche an ally.

Howard Blum wrote in The New York Times that, from 1976 onwards, party members sent reports to the FBI and local police on members of left-wing organizations. In 1977, he wrote, commercial reports on U.S. anti-apartheid groups were prepared by LaRouche members for the South African government; student dissidents were reported to the Shah of Iran's Savak

secret police; and the anti-nuclear movement was investigated on behalf of power companies. By the late 1970s, members were exchanging almost daily information with Roy Frankhouser

, a government informant and infiltrator of both far right and far left groups who was involved with the Ku Klux Klan

and the American Nazi Party

.

The LaRouche organization believed Frankhouser to be a federal agent who had been assigned to infiltrate right-wing and left-wing groups, and that he had evidence that these groups were actually being manipulated or controlled by the FBI and other agencies.

LaRouche and his associates considered Frankhouser to be a valuable intelligence contact, and took his links to extremist groups to be a cover for his intelligence work. Frankhouser played into these expectations, misrepresenting himself as a conduit for communications to LaRouche from "Mr. Ed", an alleged CIA contact, who did not exist.

Blum wrote that, at around this time, LaRouche's Computron Technologies Corporation included Mobil Oil and Citibank among its clients; that his World Composition Services had one of the most advanced typesetting complexes in the city and had the Ford Foundation among its clients; and that his PMR Associates produced the party's publications and some high school newspapers.

Around the same time, according to Blum, LaRouche was telling his membership several times a year that he was being targeted for assassination, including by the Queen of England, Zionist mobsters, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Justice Department, and the Mossad. LaRouche sued the City of New York in 1974, saying that CIA and British spies had brainwashed his associates into killing him. He has repeatedly asserted that he is a target for assassination

. According to the Patriot-News of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, LaRouche said he had been "threatened by Communists, Zionists, narcotics gangsters, the Rockefellers and international terrorists." LaRouche later said that,

In 1975, under the name Lyn Marcus, LaRouche published Dialectical Economics: An Introduction to Marxist Political Economy, called his "magnum opus" by one observer and described by its only reviewer as "the most peculiar and idiosyncratic" introduction to economics he had ever seen. Mixing economics, history, anthropology, sociology and a surprisingly large helping of business administration, the work argued that most prominent Marxists had misunderstood Marx, and that bourgeois economics arose when philosophy took a wrong, reductionist

turn under British empiricists like Locke

and Hume

.

In 1976, LaRouche campaigned for the first time in a presidential election as a U.S. Labor Party candidate, polling 40,043 votes (0.05 percent). It was the first of eight presidential elections he took part in between 1976 and 2004, which enabled him to attract $5.9 million in federal matching funds

; candidates seeking their party's presidential nomination qualify for matching funds if they raise $5,000 in each of at least 20 states. His platform predicted financial disaster by 1980 accompanied by famine and the virtual extinction of the human race within 15 years, and proposed a debt moratorium; nationalization of banks; government investment in industry especially in the aerospace sector, and an "International Development Bank" to facilitate higher food production. When Legionnaires' disease appeared in the U.S. that year, he said it was a continuation of the swine flu outbreak

, and that senators who opposed vaccination were suppressing the link as part of a "genocidal policy."

His campaign included a paid half-hour television address, which allowed him to air his views before a national audience, something that became a regular feature of his later campaigns. There were protests about this, and about the involvement of the NCLC in public life generally. Writing in The Washington Post, Stephen Rosenfeld

said LaRouche's ideas belonged to the radical right, neo-Nazi fringe, and that his main interests lay in disruption and disinformation; Rosenfeld called the NCLC one of the "chief polluters" of political democracy, citing an article in Crawdaddy

that said LaRouche members had attacked the SWP in Detroit, reportedly beating a paraplegic member with clubs. Rosenfeld argued that the press should be "chary" of offering them print or air time: "A duplicitous violence-prone group with fascistic proclivities should not be presented to the public, unless there is reason to present it in those terms." LaRouche wrote in 1999 that this comment had "openly declared... a policy of malicious lying" against him.

, was a leading activist in the German branch of the movement. She went on to work closely with LaRouche for the rest of his career, standing for election in Germany in 1980 for his Europäische Arbeiterpartei (European Workers Party), and founding the Schiller Institute

in Germany in 1984. Paul Kacprzak, who worked for LaRouche in the 1970s, told The Washington Post that Zepp had a profound effect on the movement, and that it basically became a German organization. "We'd have classes in German. They'd be teaching German language. We'd be reading German poetry." He said LaRouche sent round a memo that, when he was elected president, his wedding anniversary would be a holiday and all workers would be given a week off.

. Democratic Party leaders refused to recognize LaRouche as a party member, or to seat the few delegates he received in his seven primary campaigns as a Democrat. His campaign platforms included a return to the Bretton Woods system

, including a gold-based national and world monetary system; fixed exchange rates; and ending the International Monetary Fund

. He supported the replacement of the central bank

system, including the U.S. Federal Reserve System

, with a national bank

; a war on drug trafficking and prosecution of banks involved in money laundering; building a tunnel under the Bering Strait; the building of nuclear power plants; and a crash program to build particle beam weapon

s and lasers, including support for elements of the Strategic Defense Initiative

(SDI). He opposed the Soviet Union and supported a military build-up to prepare for imminent war; supported the screening and quarantine of AIDS

patients; and opposed environmentalism, deregulation, outcome-based education, and abortion.

In December 1980, LaRouche and his followers started what came to be known as the "October Surprise" allegation, namely that in October 1980 Ronald Reagan's campaign staff conspired with the Iranian government during the Iran hostage crisis

to delay the release of 52 American hostages held in Iran, with the aim of helping Reagan win the 1980 presidential election

against Jimmy Carter

. The Iranians had agreed to this, according to the theory, in exchange for future weapons sales from the Reagan administration. The first publication of the story was in LaRouche's Executive Intelligence Review on December 2, 1980, followed by his New Solidarity on September 2, 1983, alleging that Henry Kissinger

, one of LaRouche's regular targets, had met Iran's Ayatollah Beheshti in Paris, according to Iranian sources in Paris. Although ultimately discredited, the story was widely discussed in conspiracy circles during the 1980s and 1990s.

, maintaining frequent contact until her assassination in October 1984. His movement engaged in intensive outreach work in Latin America, producing research papers and gaining access to top government officials, including Peruvian President Alan García. LaRouche met with Mexican president José López Portillo

. George Johnson writes that LaRouche warned Portillo about attempts by international bankers to wreck the Mexican economy, meeting him under the auspices of LaRouche's National Democratic Policy Committee. Both the American Embassy and the Democratic Party issued disclaimers; a Mexican official told The New York Times that LaRouche had arranged the meeting by representing himself as a Democratic Party official. He also met Argentine's president Raúl Alfonsin

. In 1982 he authored Operation Juárez, described by Dennis King as "a brilliant call to arms against the International Monetary Fund austerity programs." The International Monetary Fund

(IMF) was the focus of widespread popular resentment throughout Latin America, and LaRouche acquired a reputation as a serious economist in Latin America, according to King. King wrote that Fidel Castro

developed "his own version of Operation Juárez."

Mexican journalist Sergio Sarmiento wrote in the Wall Street Journal in 1989 that LaRouche's Labor Party in Mexico was used to attack the country's opposition; LaRouche members alleged that the National Action Party (PAN) were agents of the KGB, and later produced a pamphlet that "a vote for PAN is a vote for Nazism." When leaders of the Mexico Oil Workers' Union were jailed—corrupt leaders, according to Sarmiento—LaRouche said the union had been attacked by the Anglo-American Liberal Establishment, controlled by Scottish Rite Freemasonry. According to Jose I. Blandon, an adviser to Manuel Noriega

—the military dictator of Panama from 1983 to 1989—LaRouche had ties to Noriega, and according to Sarmiento, LaRouche members harassed the opposition in Lima, Peru, in support of President Alan García.

LaRouche also met Turkish Prime Minister Turgut Özal

in 1987; according to the San Francisco Chronicle, Özal reprimanded his aides who had mistaken LaRouche for the Democratic Presidential candidate.

, near Leesburg, Loudoun County, Virginia. The property was owned at the time by a company registered in Switzerland. Companies associated with LaRouche continued to buy property in the area, including part of Leesburg's industrial park, purchased by LaRouche's Lafayette/Leesburg Ltd. Partnership to develop a printing plant and office complex.

Neighbors said they saw LaRouche guards in camouflage clothes carrying semi-automatic weapons, and the Post wrote that the house had sandbag-buttressed guard posts nearby, along with metal spikes in the driveway and cement barriers on the road. One of his aides said LaRouche was safer in Loudoun County: "The terrorist organizations which have targeted Mr. LaRouche do not have bases of operations in Virginia." LaRouche said his new home meant a shorter commute to Washington. A former associate said the move also meant his members would be more isolated from friends and family than they had been in New York. According to the Post in 2004, local people who opposed him for any reason were accused in LaRouche publications of being commies, homosexual, drug pushers, and terrorists. He reportedly accused the Leesburg Garden Club of being a nest of Soviet sympathizers, and a local lawyer who opposed LaRouche on a zoning matter went into hiding after threatening phone calls and a death threat. In leaflets supporting his application of concealed weapons permits for his bodyguards in Leesburg, Virginia

, he wrote:

Regarding LaRouche's paramilitary

security force, armed with semi-automatic weapons, a spokesperson said that they were necessary because LaRouche was the subject of "assassination conspiracies".

—the Democratic Party's Presidential candidate—a Soviet agent of influence, triggering over 1,000 telephone complaints. On April 19, 1986, NBC's Saturday Night Live aired a sketch satirizing the ads, portraying the Queen of England and Henry Kissinger as drug dealers. LaRouche received 78,773 votes in the 1984 presidential election.

In 1984, media reports stated that LaRouche and his aides had met Reagan administration officials, including Norman Bailey, senior director of international economic affairs for the National Security Council (NSC), and Richard Morris, special assistant to William P. Clark, Jr.

There were also reported contacts with the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the CIA. The LaRouche campaign said the reporting was full of errors. In 1984 two Pentagon officials spoke at a LaRouche rally in Virginia; a Defense Department spokesman said the Pentagon viewed LaRouche's group as a "conservative group ... very supportive of the administration." White House spokesman Larry Speakes

said the Administration was "glad to talk to" any American citizen who might have information. According to Bailey, the contacts were broken off when they became public. Three years later, LaRouche blamed his criminal indictment on the NSC, saying he had been in conflict with Oliver North

over LaRouche's opposition to the Nicaraguan Contras

. According to a LaRouche publication, a court-ordered search of North's files produced a May 1986 telex from Iran–Contra defendant General Richard Secord

, discussing the gathering of information to be used against LaRouche. King states that LaRouche's Executive Intelligence Review was the first to report on important details of the Iran–Contra affair, predicting that a major scandal was about to break months before mainstream media picked up on the story.

The LaRouche campaign supported Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative

The LaRouche campaign supported Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative

(SDI). Dennis King wrote that LaRouche had been speculating about space-based weaponry as early as 1975. He set up the Fusion Energy Foundation, which held conferences and tried to cultivate scientists, with some success. According to King, LaRouche's associates had for some years been in contact with members of the Reagan administration about LaRouche's space-based weapons ideas. Physicist Edward Teller

, a proponent of SDI and X-ray lasers, told reporters in 1984 that he had been courted by LaRouche, but had kept his distance. LaRouche began calling his plan the "LaRouche-Teller proposal," though they had never met. Teller said LaRouche was "a poorly informed man with fantastic conceptions." LaRouche later attributed the collapse of the Soviet Union

to its refusal to follow his advice to accept Reagan's offer to share the technology.

. The reports said an investigation by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) would lead to an indictment, and quoted Irwin Suall

, the Anti-Defamation League's (ADL) fact-finding director, who called LaRouche a "small-time Hitler." After the broadcast, LaRouche members picketed NBC's office carrying signs saying "Lynch Pat Lynch," and the NBC switchboard said it received a death threat against her. Another NBC researcher said someone placed fliers around her parents' neighborhood saying she was running a call-girl ring from her parents' home. Lynch said LaRouche members began to impersonate her and her researchers in telephone calls, and called her "Fat Lynch" in their publications.

LaRouche filed a defamation suit against NBC and the ADL, arguing that the programs were the result of a deliberate campaign of defamation against him. The judge ruled that NBC need not reveal its sources, and LaRouche lost the case. NBC won a countersuit, the jury awarding the network $3 million in damages, later reduced to $258,459, for misuse of libel law, in what was called one of the more celebrated countersuits by a libel defendant. LaRouche failed to pay the damages, pleading poverty, which the judge described as "completely lacking in credibility." LaRouche said he had been unaware since 1973 who paid the rent on the estate, or for his food, lodging, clothing, transportation, bodyguards, and lawyers. The judge fined him for failing to answer. After the judge signed an order to allow discovery of LaRouche's personal finances, a cashier's check was delivered to the court to end the case. When LaRouche appealed, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals

, rejecting his arguments, set forth a three-pronged test, later called the "LaRouche test," to decide when anonymous sources must be named in libel cases.

seemed to fulfill LaRouche's 1973 prediction that an epidemic would strike humanity in the 1980s. LaRouche said it had been created by the "Soviet war machine," or by the International Monetary Fund to kill "excess eaters" in Africa. According to Christopher Toumey, his subsequent campaign followed a familiar LaRouche pattern: challenging the scientific competence of government experts, and arguing that LaRouche had special scientific insights, and his own scientific associates were more competent than government scientists. LaRouche's view of AIDS agreed with orthodox medicine in that HIV caused AIDS, but differed from it in arguing that HIV spread like the cold virus or malaria, by way of casual contact and insect bites—an idea that would make HIV-positive people extremely dangerous. He said "a person with AIDS running around is like a person with a machine gun running around", and that people who lynched gays might be remembered as the "only political force which acted to save the human species from extinction." He advocated testing anyone working in schools, restaurants, or healthcare, and quarantining those who tested positive. Some of LaRouche's views on AIDS were developed by John Seale, a British venereological physician who proposed that AIDS was created in a laboratory. Seale's highly speculative writings were published in three prestigious medical journals, lending these ideas some appearance of being hard science.

LaRouche and his associates devised a "Biological Strategic Defense Initiative" that would cost $100 billion per annum, which they said would have to be directed by LaRouche. Toumey writes that those opposing the program, such as the World Health Organization

and Centers for Disease Control, were accused of "viciously lying to the world," and of following an agenda of genocide and euthanasia. In 1986 LaRouche proposed that AIDS be added to California's List of Communicable Diseases. Sponsored by his "Prevent AIDS Now Initiative Committee" (PANIC), Proposition 64—or the "LaRouche initiative"—qualified for the California ballot in 1986, with the required signature gatherers mostly paid for by LaRouche's Campaigner Publications. Seale, presented as an AIDS expert by PANIC, supported the LaRouche initiative but disagreed with several of LaRouche's views, including that HIV could be spread by insects, and described the group's political beliefs and conspiracy theories as "rather odd". According to David Kirp, professor of public policy at the University of California at Berkeley, the proposal would have required that 300,000 people in the area with HIV or AIDS be reported to public health authorities; might have removed over 100,000 of them from their jobs in schools, restaurants and agriculture; and would have forced 47,000 children to stay away from school.

The proposal was opposed by leading scientists and local health officials—including the deans and faculties of four California schools of public health, scientists at Stanford University, the Red Cross, the surgeon general, labor unions and the Democratic Party of California—as based on inaccurate scientific information and, as the public health schools put it, running "counter to all public health principles." It was defeated, reintroduced two years later, and defeated again, with two million votes in favor the first time, and 1.7 million the second. AIDS became a leading plank in LaRouche's platform during his 1988 presidential campaign. He vowed to quarantine its "aberrant" victims who were "guilty of bringing this pandemic upon us."

, withdrew his nomination rather than run on the same slate as LaRouche members, and told reporters the party was "exploring every legal remedy to purge these bizarre and dangerous extremists from the Democratic ticket." A spokesman for the Democratic National Committee said it would have to do a better job of communicating to the electorate that LaRouche's National Democratic Policy Committee was unrelated to the Democratic Party. The New York Times wrote that Democratic Party officials were trying to identify LaRouche candidates in order to alert voters, and asked the LaRouche organization to release a full list of its candidates.

A month later, LaRouche held a press conference to accuse the Soviet government, British government, drug dealers, international bankers, and journalists of being involved in a variety of conspiracies. Flanked by bodyguards, he said, "If Abe Lincoln were alive, he'd probably be standing up here with me today," and that there was no criticism of him that did not originate "with the drug lobby or the Soviet operation ..." He said he had been in danger from Soviet assassins for over 13 years, and had to live in safe houses. He refused to answer a question from an NBC reporter, saying "How can I talk with a drug pusher like you?" He called the leadership of the United States "idiotic" and "berserk," and its foreign policy "criminal or insane." He warned of the imminent collapse of the banking system and accused banks of laundering drug money. Asked about the movement's finances, he said "I don't know. ... I'm not responsible, I'm not involved in that."

In October 1986, hundreds of state and federal officers raided LaRouche offices in Virginia and Massachusetts. A federal grand jury indicted LaRouche and 12 associates on credit card fraud and obstruction of justice; the charges included that they had attempted to defraud people of millions of dollars, including several elderly people, by borrowing money they did not intend to repay. LaRouche's "heavily fortified" estate was surrounded and he at first warned law-enforcement officials not to arrest him, saying any attempt to do so would be an attempt to kill him; a spokesman would not rule out the use of violence against officials in response. While surrounded, LaRouche sent a telegraph to President Ronald Reagan saying that an attempt to arrest him "would be an attempt to kill me. I will not submit passively to such an arrest, but ... I will defend myself." LaRouche disputed the charges, alleging that the trials were politically motivated. A number of LaRouche entities, including the Fusion Energy Foundation, were taken over through an involuntary bankruptcy proceeding in 1987; the government's use of the sealed order was regarded as a rare legal maneuver.

In October 1986, hundreds of state and federal officers raided LaRouche offices in Virginia and Massachusetts. A federal grand jury indicted LaRouche and 12 associates on credit card fraud and obstruction of justice; the charges included that they had attempted to defraud people of millions of dollars, including several elderly people, by borrowing money they did not intend to repay. LaRouche's "heavily fortified" estate was surrounded and he at first warned law-enforcement officials not to arrest him, saying any attempt to do so would be an attempt to kill him; a spokesman would not rule out the use of violence against officials in response. While surrounded, LaRouche sent a telegraph to President Ronald Reagan saying that an attempt to arrest him "would be an attempt to kill me. I will not submit passively to such an arrest, but ... I will defend myself." LaRouche disputed the charges, alleging that the trials were politically motivated. A number of LaRouche entities, including the Fusion Energy Foundation, were taken over through an involuntary bankruptcy proceeding in 1987; the government's use of the sealed order was regarded as a rare legal maneuver.

He received 25,562 votes in the 1988 presidential election, standing under the banner of the "National Economic Recovery" party. On December 16 that year, he was convicted of conspiracy to commit mail fraud involving more than $30 million in defaulted loans; 11 counts of actual mail fraud involving $294,000 in defaulted loans; and one count of conspiring to defraud the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. He was sentenced to fifteen years, but was released on January 26, 1994. The judge called his claim of a political vendetta "arrant nonsense," and said "the idea that this organization is a sufficient threat to anything that would warrant the government bringing a prosecution to silence them just defies human experience." Thirteen associates received terms ranging from one month to 77 years for mail fraud and conspiracy. Defense lawyers filed unsuccessful appeals that challenged the conduct of the grand jury, the contempt fines, the execution of the search warrants, and various trial procedures. At least ten appeals were heard by the United States Court of Appeals, and three by the U.S. Supreme Court. Former Attorney General

Ramsey Clark

joined the defense team for two appeals, writing that the case involved "a broader range of deliberate and systematic misconduct and abuse of power over a longer period of time in an effort to destroy a political movement and leader, than any other federal prosecution in my time or to my knowledge."

In his 1988 autobiography, LaRouche says the raid on his operation was the work of Raisa Gorbachev. In an interview the same year, he said that the Soviet Union opposed him because he invented the Strategic Defense Initiative

. "The Soviet government hated me for it. Gorbachev also hated my guts and called for my assassination and imprisonment and so forth." LaRouche asserted that he has survived these threats because of protection by unnamed U.S. government officials. "Even when they don't like me, they consider me a national asset, and they don't like to have their national assets killed."

In 1989 LaRouche advocated that classical orchestras should return to the "Verdi pitch," a pitch that Verdi

had enshrined in Italian legislation in 1884. The initiative attracted support from more than 300 opera stars, including Joan Sutherland

, Placido Domingo

and Luciano Pavarotti

, who according to Opera Fanatic may or may not have been aware of LaRouche's politics. A spokesman for Domingo said Domingo had simply signed a questionnaire, had not been aware of its origins, and would not agree with LaRouche's politics. Renata Tebaldi

and Piero Cappuccilli

, who were running for the European Parliament on LaRouche's "Patriots for Italy" platform, attended Schiller Institute conferences as featured speakers, and the discussions led to debates in the Italian parliament about reinstating Verdi's legislation. LaRouche gave an interview to National Public Radio on the initiative from prison. The initiative was opposed by the editor of Opera Fanatic, Stefan Zucker

, who objected to the establishment of a "pitch police," and argued that LaRouche was using the issue to gain credibility.

in Rochester, Minnesota. From there he ran for Congress in 1990, seeking to represent the 10th District of Virginia

, but received less than one percent of the vote. He ran for President again in 1992 with James Bevel

as his running mate, a civil rights activist who had represented the LaRouche movement in its pursuit of the Franklin child prostitution ring allegations

. It was only the second-ever campaign for president from prison. He received 26,334 votes, standing again as the "Economic Recovery" party. For a time he shared a cell with televangelist Jim Bakker

. Bakker later wrote of his astonishment at LaRouche's detailed knowledge of the Bible. According to Bakker, LaRouche received a daily intelligence report by mail, and at times had information about news events days before they happened. Bakker also wrote that LaRouche believed their cell was bugged. In Bakker's view, "to say LaRouche was a little paranoid would be like saying that the Titanic had a little leak."

LaRouche was released on parole in January 1994, and returned to Loudoun County. The Washington Post wrote that he would be supervised by parole and probation officers until January 2004. Also in 1994, his followers joined members of the Nation of Islam

to condemn the Anti-Defamation League for its alleged crimes against African Americans, reportedly one of several such meetings since 1992. In 1996, LaRouche was invited to speak at a convention organized by the Nation of Islam's Louis Farrakhan

and Ben Chavis, then of the National African American Leadership Summit. As soon as he began speaking, he was booed off the stage; one delegate said it was because of his actions against African Americans in the past.

In the 1996 Democratic presidential primaries

, he received enough votes in Louisiana and Virginia to get one delegate from each state, but before the primaries began, the Democratic National Committee chair, Donald Fowler

, ruled that LaRouche was not a "bona fide Democrat" because of his "expressed political beliefs ... which are explicitly racist and anti-Semitic," and because of his "past activities including exploitation of and defrauding contributors and voters." Fowler instructed state parties to disregard votes for LaRouche.

LaRouche opposed attempts to impeach President Bill Clinton

, charging it was a plot by the British Intelligence to destabilize the U.S. Government. In 1996 he called for the impeachment of Pennsylvania governor Tom Ridge

.

In 1999 China's press agency, the Xinhua News Agency

, reported that LaRouche had criticized the Cox Report

, a congressional investigation that accused the Chinese of stealing U.S. nuclear weapons secrets, calling it a "scientifically illiterate hoax." On October 13, 1999, during a press conference to announce his plans to run for president, he predicted the collapse of the world's financial system, stating, "There's nothing like it in this century.... it is systematic, and therefore, inevitable." He said the U.S. and other nations had built the "biggest financial bubble in all history," which was close to bankruptcy.

LaRouche founded the Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement (WLYM) in 2000, saying in 2004 that it had hundreds of members in the U.S. and a lesser number overseas. During the Democratic primaries in June 2000, he received 53,280 votes, or 22 percent of the total, in Arkansas.

LaRouche founded the Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement (WLYM) in 2000, saying in 2004 that it had hundreds of members in the U.S. and a lesser number overseas. During the Democratic primaries in June 2000, he received 53,280 votes, or 22 percent of the total, in Arkansas.

In 2002 LaRouche's Executive Intelligence Review argued that the September 11, 2001 attacks had been an "inside job"

and "attempted coup d'etat," and that Iran was the first country to question it. The article received wide coverage in Iran, and was cited by senior Iranian government officials, including Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

and Hassan Rowhani

. Mahmoud Alinejad writes that, in a subsequent telephone interview with the Voice of the Islamic Republic of Iran, LaRouche said American and Israeli elements had organized the attacks to start a war, and that Israel was a dictatorial regime prepared to commit Nazi-style crimes against the Palestinians.

LaRouche again entered the primary elections for the Democratic Party's nomination in 2004, setting a record for the number of consecutive presidential campaigns; Democratic Party officials distanced themselves from him and did not allow him to participate in candidate forum debates. He did not run in 2008.

As during the preceding decade, LaRouche and his followers denied that human civilization had harmed the environment through DDT, chluorofluorocarbons, or carbon dioxide. According to Chip Berlet, "Pro-LaRouche publications have been at the forefront of denying the reality of global warming".

in 1988 and German unification. He said LaRouche had urged the West to pursue a policy of economic cooperation similar to the Marshall Plan

for the advancement of the economy of the socialist countries. According to Qazwini, recent years have seen a proliferation of LaRouche's ideas in China and South Asia. Qazwini referred to him as the spiritual father of the revival of the new Silk Road or Eurasian Landbridge, which aims to link the continents through a network of ground transportation. In November 2005, an eight-part interview with LaRouche was published in the People's Daily

of China, covering his economic forecasts, his battles with the American media, and his assessment of the neoconservatives. The interviewer wrote that LaRouche was "quite famous in mainland China today," and seemed to be better known overseas than in America.

Tatiana Shishova interviewed him for Russia Today

in 2008, describing him as "the greatest American economist, a prominent politician, one of the first to struggle with the financial oligarchy and its major institutions—the World Bank and IMF. He has no equal in the field of economic and financial forecasts." LaRouche gave an interview in 2009 to China Youth Daily

, which wrote that he had warned in July 2007 that unless the United States stopped monopolizing world finances, and united with China, Russia, and India to reorganize the world financial system, a new global credit crisis would be unavoidable.

as having forecast the financial crisis of 2007–2009. In December 2008, Ivo Caizzi of Corriere della Sera

referred to him as "the guru politician who, since the nineties, has announced the crash of speculative finances and the need for a New Bretton Woods

." The article said Italian Economics Minister Giulio Tremonti

was "an attentive reader" of LaRouche's anti-Free Market and anti-Marxist writings. Italian Senator Oskar Peterlini

, in a July 2009 speech before the Senate, called LaRouche an expert in the field who had predicted the crisis.

During the discussion of U.S. health care reform in 2009, LaRouche took exception to what he described as Barack Obama

's proposal that "independent boards of doctors and health care experts [should] make the life-and-death decisions of what care to provide, and what not, based on cost-effectiveness criteria." LaRouche said the proposed boards, later compared to "death panels" by Sarah Palin

, would amount to the same thing as the Nazis' Action T4

euthanasia program, and urged Americans to "quickly and suddenly change the behavior of this president ... for no lesser reason than that your sister might not end up in somebody's gas oven." His movement printed pamphlets showing Obama and Hitler

laughing together, and posters of Obama with a Hitler-style mustache. In Seattle, police were called twice in response to people threatening to tear the posters apart, or to assault the LaRouche supporters holding them. During one widely reported public meeting, Congressman Barney Frank

referred to the posters as "vile, contemptible nonsense."

, LaRouche believes that a super elite (the "oligarchy") is in control of world events, a group that includes the Rockefellers, the London financial center, the British royal family, the Anti-Defamation League, the KGB, and the Heritage Foundation itself. Others include Nazis, Jesuits, Freemasons, Communists, Trilateralists, international bankers, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Socialist International—all supposedly controlled by the British—as well as Hitler, H.G. Wells, Voltaire, and the Beatles as representatives of the 1960s counterculture

. George Johnson

in Architects of Fear (1983) compares the view to the Illuminati conspiracy theory; after he wrote about LaRouche in The New York Times, LaRouche's followers denounced Johnson as part of a conspiracy of elitists that began in ancient Egypt.

LaRouche sees history as a battle between Platonists

, who believe in absolute truth, and Aristotelians

, who rely on empirical

data. Platonists in LaRouche's view include figures such as Beethoven, Mozart, Shakespeare, Leonardo da Vinci

, and Leibniz. He believes that many of the world's ills result from the dominance of Aristotelianism as embraced by the empirical philosophers (such as Hobbes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume), leading to a culture that favors the empirical over the metaphysical

, embraces moral relativism

, and seeks to keep the general population uninformed. Industry, technology, and classical music should be used to enlighten the world, LaRouche argues, whereas the Aristotelians use psychotherapy, drugs, rock music, jazz, environmentalism, and quantum theory to bring about a new dark age in which the world will be ruled by the oligarchs. Left and right are false distinctions for LaRouche; what matters is the Platonic versus Aristotelian outlook, a position that has led him to form relationships with groups as disparate as farmers, nuclear engineers, Black Muslims, Teamsters and pro-life advocates. The conspirators may not be in touch with one another: "From their standpoint, [the conspirators] are proceeding by instinct," LaRouche has said. "If you're asking how their policy is developed—if there is an inside group sitting down and making plans—no, it doesn't work that way ... History doesn't function quite that consciously."

LaRouche maintained that he was anti-Zionist, not anti-Semitic. When the ADL accused him of anti-Semitism in 1979, he filed a $26-million libel suit; Justice Michael Dontzin of the New York Supreme Court ruled that it was fair comment, and that the facts "reasonably give rise" to that description. LaRouche said in 1986 that descriptions of him as a neo-fascist or anti-Semite stemmed from "the drug lobby or the Soviet operation—which is sometimes the same thing," and in 2006 wrote that "religious and racial hatred, such as anti-Semitism, or hatred against Islam, or, hatred of Christians, is, on record of known history, the most evil expression of criminality to be seen on the planet today." Antony Lerman wrote in 1988 that LaRouche used "the British" as a code word for "Jews," a theory also propounded by Dennis King, author of Lyndon LaRouche and the New American Fascism (1989). George Johnson argued that King's presentation failed to take into account that several members of LaRouche's inner circle were themselves Jewish. Daniel Pipes

wrote in 1997 that LaRouche's references to the British really were to the British, though he agreed that an alleged British-Jewish alliance lay at the heart of LaRouche's conspiracism.

Manning Marable

of Columbia University wrote in 1998 that LaRouche tried in the mid-1980s to build bridges to the black community. Marable argued that most of the community was not fooled, and quoted the A. Philip Randolph Institute

, an organization for African-American trade unionists, declaring that "LaRouche appeals to fear, hatred and ignorance. He seeks to exploit and exacerbate the anxieties and frustrations of Americans by offering an array of scapegoats and enemies: Jews, Zionists, international bankers, blacks, labor unions-much the way Hitler did in Germany." During LaRouche's slander suit against NBC in 1984, Roy Innis

, leader of the Congress of Racial Equality

, took the stand for LaRouche as a character witness, stating under oath that LaRouche's views on racism were "consistent with his own." Asked whether he had seen any indication of racism in LaRouche's associates, he replied that he had not. Innis received criticism from many blacks for having testified on LaRouche's behalf.

A 1987 article by John Mintz in The Washington Post reported that members lived hand-to-mouth in crowded apartments, their basic needs—such as a mattress and pillowcase—paid for by the movement. Their days were focused on raising money or selling newspapers for LaRouche, doing research for him, or singing in a group choir, spending almost every waking hour together.

According to Christopher Toumey, LaRouche's charismatic authority

within the movement is grounded on members' belief that he possesses a unique level of insight and expertise. He identifies an emotionally charged issue, conducts in-depth research into it, then proposes a simplistic solution, usually involving restructuring of the economy or national security apparatus. He and the membership portray anyone opposing him as immoral and part of the conspiracy. The group is known for its caustic attacks on people it opposes and former members. In the past it has justified what it refers to as "psywar techniques" as necessary to shake people up; Johnson in 1983 quoted a LaRouche associate: "We're not very nice, so we're hated. Why be nice? It's a cruel world. We're in a war and the human race is up for grabs." Charles Tate, a former long-term LaRouche associate, told The Washington Post in 1987 that members see themselves as not subject to the ordinary laws of society: "They feel that the continued existence of the human race is totally dependent on what they do in the organization, that nobody would be here without LaRouche. They feel justified in a peculiar way doing anything whatsoever."

Newspaper archives of material on LaRouche

LaRouche movement

The LaRouche movement is an international political and cultural network that promotes Lyndon LaRouche and his ideas. It has included scores of organizations and companies around the world. Their activities include campaigning, private intelligence gathering, and publishing numerous periodicals,...

. Often described as a political extremist, he has written prolifically in his publications on economic, scientific, and political topics, as well as on history, philosophy, and psychoanalysis, largely promoting a conspiracist view of history and current affairs.

LaRouche was a perennial presidential candidate from 1976 to 2004, running once for his own U.S. Labor Party

U.S. Labor Party

The U.S. Labor Party was a political party formed in 1973 by the National Caucus of Labor Committees . It served as a vehicle for Lyndon LaRouche to run for President of the United States in 1976, but it also sponsored many candidates for local offices and Congressional and Senate seats between...

and campaigning seven times for the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

nomination, though he failed to attract appreciable electoral support. He was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment in 1988 for conspiracy to commit mail fraud and tax code violations, but continued his political activities from behind bars until his release in 1994 on parole. Ramsey Clark

Ramsey Clark

William Ramsey Clark is an American lawyer, activist and former public official. He worked for the U.S. Department of Justice, which included service as United States Attorney General from 1967 to 1969, under President Lyndon B. Johnson...

, his chief appellate attorney and a former U.S. Attorney General, argued that LaRouche was denied a fair trial but the Court of Appeals unanimously rejected the appeal.

Members of the LaRouche movement see LaRouche as a political leader in the tradition of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

. Other commentators, including The Washington Post and The New York Times, have described him over the years as a conspiracy theorist, fascist, and anti-Semite, and have characterized his movement as a cult. Norman Bailey

Norman Bailey (government official)

Norman A. Bailey is President of the Institute for Global Economic Growth, an international economic consultant, a professor of economic statecraft, and a former US government official.-Employment at the National Security Council:...

, formerly with the National Security Council

United States National Security Council

The White House National Security Council in the United States is the principal forum used by the President of the United States for considering national security and foreign policy matters with his senior national security advisors and Cabinet officials and is part of the Executive Office of the...

, described LaRouche's staff in 1984 as one of the best private intelligence services in the world, while the Heritage Foundation

Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation is a conservative American think tank based in Washington, D.C. Heritage's stated mission is to "formulate and promote conservative public policies based on the principles of free enterprise, limited government, individual freedom, traditional American values, and a strong...

, a conservative think tank, wrote that he leads "what may well be one of the strangest political groups in American history."

Early life

LaRouche was born in Rochester, New Hampshire, the eldest of three children of Lyndon H. LaRouche, Sr. and Jessie Lenore. His father worked for the United Shoe Machinery Corporation in Rochester before the family moved to Lynn, Massachusetts. LaRouche described his childhood as that of "an egregious child, I wouldn't say an ugly duckling but a nasty duckling." According to his autobiography, The Power of Reason: A Kind of an Autobiography (1979), LaRouche began to read around the age of five, and was called "Big Head" by other children at his school. He recalls that in the third grade his eyesight was poor and he was made to sit at the back of the class, where his vision remained blurred.His parents became Quakers

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

after his father had converted from Roman Catholicism, and his mother from Protestantism. They forbade him from fighting with other children, even in self-defense, which he said led to "years of hell" from bullies at school. As a result, he spent much of his time alone, taking long walks through the woods and identifying in his mind with great philosophers. He wrote that, between the ages of twelve and fourteen, he read philosophy extensively, embracing the ideas of Leibniz

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a German philosopher and mathematician. He wrote in different languages, primarily in Latin , French and German ....

, and rejecting those of Hume

David Hume

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He was one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment...

, Bacon

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

, Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

, Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

, Berkeley

George Berkeley

George Berkeley , also known as Bishop Berkeley , was an Irish philosopher whose primary achievement was the advancement of a theory he called "immaterialism"...

, Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer of 18th-century Romanticism. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution as well as the overall development of modern political, sociological and educational thought.His novel Émile: or, On Education is a treatise...

, and Kant

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant was a German philosopher from Königsberg , researching, lecturing and writing on philosophy and anthropology at the end of the 18th Century Enlightenment....

. He graduated from Lynn's English High School

English High School (Lynn, Massachusetts)

Lynn English High School is a historic high school located at 50 Goodridge Street in Lynn, Massachusetts. A diverse, public high school, Lynn English is the rival of Lynn Classical High School. Enrollment is approximately 1635 students .-History:...

in 1940. In the same year, the Lynn Quakers expelled his father from the group, for reportedly accusing other Quakers of misusing funds, while writing under the pen name Hezekiah Micajah Jones. LaRouche and his mother resigned in sympathy for his father.

University studies, the army, marriage

LaRouche attended Northeastern University in Boston and left in 1942. He later wrote that his teachers "lacked the competence to teach me on conditions I was willing to tolerate." As a Quaker, he was a conscientious objectorConscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, and/or religion....

(CO) during World War II, and joined a Civilian Public Service

Civilian Public Service

The Civilian Public Service provided conscientious objectors in the United States an alternative to military service during World War II...

camp, where, in the words of Dennis King, he "promptly joined a small faction at odds with the administrators." In 1944 he joined the United States Army as a non-combatant and served in India and Burma with medical units and ending the war as an ordnance clerk. He described his decision to serve as one of the most important of his life. While in India he developed sympathy for the Indian Independence movement

Indian independence movement

The term Indian independence movement encompasses a wide area of political organisations, philosophies, and movements which had the common aim of ending first British East India Company rule, and then British imperial authority, in parts of South Asia...

. LaRouche wrote that many GIs feared they would be asked to support British forces in actions against Indian independence forces, and that prospect was "revolting to most of us."

He discussed Marxism

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

in the CO camp, and while traveling home on the SS General Bradley in 1946, he met Don Merrill, a fellow soldier, also from Lynn, who converted him to Trotskyism

Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the theory of Marxism as advocated by Leon Trotsky. Trotsky considered himself an orthodox Marxist and Bolshevik-Leninist, arguing for the establishment of a vanguard party of the working-class...

. Back in the U.S., he resumed his education at Northeastern University, but left because of his perception of academic "philistinism." He returned to Lynn in 1948, and the next year joined the Socialist Workers Party

Socialist Workers Party (United States)

The Socialist Workers Party is a far-left political organization in the United States. The group places a priority on "solidarity work" to aid strikes and is strongly supportive of Cuba...

(SWP), adopting the pseudonym Lyn Marcus for his political work. He arrived in New York City in 1953, where he took a job as a management consultant. In 1954 he married Janice Neuberger, a psychiatrist and member of the SWP. Their son, Daniel, was born in 1956.

Teaching and the National Caucus of Labor Committees

By 1961 the LaRouches were living in Central Park West, Manhattan, and LaRouche's activity were mostly focused on his career and not on the SWP. He and his wife separated in 1963, and he moved into a Greenwich Village apartment with another SWP member, Carol Schnitzer, also known as Larrabee. In 1964 he began an association with an SWP faction called the Revolutionary TendencyRevolutionary Tendency (SWP)

The Revolutionary Tendency within the US Socialist Workers Party was an internal faction that disagreed with the direction the leadership was taking the party on several important issues...

, a faction which was later expelled from the SWP, and came under the influence of British Trotskyist leader Gerry Healy

Gerry Healy

Thomas Gerard Healy, known as Gerry Healy , was a political activist, a co-founder of the International Committee of the Fourth International, and, according to former prominent U.S. supporter David North, the leader of the Trotskyist movement in Great Britain between 1950 – 1985...

. For six months, LaRouche worked with American Healyite leader Tim Wohlforth

Tim Wohlforth

Timothy Andrew Wohlforth , is a United States former Trotskyist leader. Since leaving the Trotskyist movement he has become a writer of crime fiction and of politically oriented non-fiction....

, who later wrote that LaRouche had a "gargantuan ego," and "a marvelous ability to place any world happening in a larger context, which seemed to give the event additional meaning, but his thinking was schematic, lacking factual detail and depth."

In 1967 LaRouche began teaching classes on Marx's dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a strand of Marxism synthesizing Hegel's dialectics. The idea was originally invented by Moses Hess and it was later developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels...

at New York City's Free School, and attracted a group of students from Columbia University and the City College of New York, recommending that they read Das Kapital

Das Kapital

Das Kapital, Kritik der politischen Ökonomie , by Karl Marx, is a critical analysis of capitalism as political economy, meant to reveal the economic laws of the capitalist mode of production, and how it was the precursor of the socialist mode of production.- Themes :In Capital: Critique of...

, as well as Hegel, Kant, and Leibniz. During the 1968 Columbia University protests

Columbia University protests of 1968

The Columbia University protests of 1968 were among the many student demonstrations that occurred around the world in that year. The Columbia protests erupted over the spring of that year after students discovered links between the university and the institutional apparatus supporting the United...

, he organized his supporters under the name the National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC). The aim of the NCLC was to win control of the Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society was a student activist movement in the United States that was one of the main iconic representations of the country's New Left. The organization developed and expanded rapidly in the mid-1960s before dissolving at its last convention in 1969...

branch—the university's main activist group—and build a political alliance between students, local residents, organized labor, and the Columbia faculty. By 1973 the NCLC had over 600 members in 25 cities—including West Berlin and Stockholm—and produced what King called the most literate of the far-left papers, New Solidarity. The NCLC's internal activities became highly regimented over the next few years. Members gave up their jobs and devoted themselves to the group and its leader, believing it would soon take control of America's trade unions and overthrow the government.

1971: "Intelligence network"

Robert J. Alexander writes that LaRouche first established an NCLC "intelligence network" in 1971. Members all over the world would send information to NCLC headquarters, which would distribute it via briefings and other publications.LaRouche organized the network as a series of news services and magazines, which commentators say was done to gain access to government officials under press cover. They included Executive Intelligence ReviewExecutive Intelligence Review

Executive Intelligence Review is a weekly newsmagazine founded in 1974 by the American political activist Lyndon LaRouche. Based in Leesburg, Virginia, it maintains offices in a number of countries, according to its masthead, including Wiesbaden, Berlin, Copenhagen, Paris, Melbourne, and Mexico City...

, founded in 1974 and known for its conspiracy theories, including that Queen Elizabeth II is the head of an international drug-smuggling cartel, and that the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing

Oklahoma City bombing

The Oklahoma City bombing was a terrorist bomb attack on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995. It was the most destructive act of terrorism on American soil until the September 11, 2001 attacks. The Oklahoma blast claimed 168 lives, including 19...

was part of a British attempt to take over the United States. Others included New Solidarity, Fusion Magazine, 21st Century Science and Technology, and Campaigner Magazine. His news services and publishers included American System Publications, Campaigner Publications, New Solidarity International Press Service, and The New Benjamin Franklin House Publishing Company. LaRouche acknowledged in 1980 that his followers impersonated reporters and others, saying it had to be done for his security. In 1982, U.S. News and World Report sued New Solidarity International Press Service and Campaigner Publications for damages, alleging that members were impersonating its reporters in phone calls.

U.S. sources told the Washington Post in 1985 that the LaRouche organization had assembled a worldwide network of government and military contacts, and that his researchers sometimes supplied information to government officials. Bobby Ray Inman

Bobby Ray Inman

Bobby Ray Inman is a retired United States admiral who held several influential positions in the U.S. Intelligence community.-Career:...

, the CIA's deputy director in 1981 and 1982, said LaRouche and his wife had visited him offering information about the West German Green Party, and a CIA spokesman said LaRouche met Deputy Director John McMahon in 1983 to discuss one of LaRouche's trips overseas. An aide to William Clark said when LaRouche's associates discussed technology or economics, they made good sense and seemed to be qualified. Norman Bailey, formerly with the National Security Council, said in 1984 that LaRouche's staff comprised "one of the best private intelligence services in the world"; he said, "They do know a lot of people around the world. They do get to talk to prime ministers and presidents." Several government officials feared a security leak from the government's ties with the movement.

According to critics, the supposed behind-the-scenes processes, were more often flights of fancy than inside information. Douglas Foster wrote in Mother Jones in 1982 that the briefings consisted of disinformation, "hate-filled" material about enemies, phony letters, intimidation, fake newspaper articles, and dirty tricks campaigns. Opponents were accused of being gay or Nazis, or were linked to murders, which the movement called "psywar techniques."

From the 1970s through to the 2000s, LaRouche founded several groups and companies. In addition to the National Caucus of Labor Committees, there was the Citizens Electoral Council

Citizens Electoral Council

The Citizens Electoral Council of Australia is a minor nationalist political party in Australia affiliated with the international LaRouche Movement, led by American political activist and conspiracy theorist Lyndon LaRouche. It reported having 549 members in 2007...

(Australia), the National Democratic Policy Committee, the Fusion Energy Foundation

Fusion Energy Foundation

Fusion Energy Foundation was a non-profit think tank cofounded by Lyndon LaRouche in 1974 in New York. It promoted the construction of nuclear power plants, research into fusion power and beam weapons and other causes. The FEF was called fusion's greatest private supporter...

, and the U.S. Labor Party. In 1984 he founded the Schiller Institute

Schiller Institute

The Schiller Institute is an international political and economic thinktank, one of the primary organizations of the LaRouche movement, with headquarters in Germany and the United States, and supporters in Australia, Canada, Russia, and South America, among others, according to its website.The...

in Germany with his second wife, and three political parties there—the Europäische Arbeiterpartei, Patrioten für Deutschland, and Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität

Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität

Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität , or the Civil Rights Movement Solidarity, is a German political party founded by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, wife of U.S. political activist Lyndon LaRouche....

—and in 2000 the Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement

Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement