Lundy

Encyclopedia

Lundy is the largest island in the Bristol Channel

, lying 12 miles (19 km) off the coast of Devon

, England, approximately one third of the distance across the channel between England and Wales. It measures about 3 by at its widest. Lundy gives its name to a British sea area and is one of the islands of England.

As of 2007, there was a resident population of 28 people, including volunteers. These include a warden, ranger, island manager, and farmer, as well as bar and house-keeping staff. Most live in and around the village at the south of the island. Most visitors are day-tripper

s, although there are 23 holiday properties and a camp site for staying visitors, mostly also around the south of the island.

In a 2005 opinion poll of Radio Times

readers, Lundy was named as Britain's tenth greatest natural wonder. The entire island has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest

and it was England's first statutory Marine Nature Reserve

, and the first Marine Conservation Zone, because of its unique flora and fauna. It is managed by the Landmark Trust

on behalf of the National Trust

.

The name Lundy is believed to come from the old Norse word for "puffin island" (Lundey), lundi being the Norse

The name Lundy is believed to come from the old Norse word for "puffin island" (Lundey), lundi being the Norse

word for a puffin

and ey, an island, although an alternative explanation has been suggested with Lund referring to a copse, or wooded area. According to genealogist Edward MacLysaght

the surname Lundy is from Norman de la Lounde, a name recorded in medieval documents in counties Tipperary

and Kilkenny

in Ireland

.

Lundy has evidence of visitation or occupation from the Neolithic

period onward, with Mesolithic

flintwork, Bronze Age

burial mounds

, four inscribed gravestones from the early medieval period, and an early medieval monastery (possibly dedicated to St Elen or St Helen).

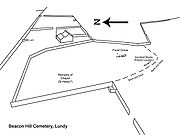

Beacon Hill cemetery was excavated by Charles Thomas

Beacon Hill cemetery was excavated by Charles Thomas

in 1969. The cemetery contains four inscribed stones, dated to the 5th or 6th century AD. The site was originally enclosed by a curvilinear bank and ditch, which is still visible in the south west corner. However, the other walls were moved when the Old Light was constructed in 1819. Early Christian enclosures of this type are known as lann

s in Cornish

. There are surviving examples in Luxulyan

, in Cornwall; Mathry

, Mydrim, and Clydey in Wales; and Stowford, Jacobstowe

, Lydford

, and Instow

, in Devon.

Thomas proposed a five-stage sequence of site usage:

(1) An area of round huts

and fields. These huts may have fallen into disuse before the construction of the cemetery.

(2) The construction of the focal grave, an 11 ft by 8 ft rectangular stone enclosure containing a single cist

grave. The interior of the enclosure was filled with small granite pieces. Two more cist graves located to the west of the enclosure may also date from this time.

(3) Perhaps 100 years later, the focal grave was opened and the infill removed. The body may have been moved to a church at this time.

(4) & (5) Two further stages of cist grave construction around the focal grave.

23 cist graves were found during this excavation. Considering that the excavation only uncovered a small area of the cemetery, there may be as many as 100 graves.

Four Celtic inscribed stone

Four Celtic inscribed stone

s have been found in Beacon Hill cemetery:

by Henry II

in 1160. The Templars were a major international maritime force at this time, with interests in North Devon, and almost certainly an important port at Bideford

or on the River Taw

in Barnstaple

. This was probably because of the increasing threat posed by the Norse

sea raiders; however, it is unclear whether they ever took possession of the island. Ownership was disputed by the Marisco family who may have already been on the island during King Stephen

's reign. The Mariscos were fined, and the island was cut off from necessary supplies. Evidence of the Templars' weak hold on the island came when King John

, on his accession in 1199, confirmed the earlier grant.

In 1235 William de Marisco was implicated in the murder of Henry Clement, a messenger of Henry III

In 1235 William de Marisco was implicated in the murder of Henry Clement, a messenger of Henry III

. Three years later, an attempt was made to kill Henry III by a man who later confessed to being an agent of the Marisco family. William de Marisco fled to Lundy where he lived as a virtual king. He built a stronghold in the area now known as Bulls' Paradise with 9 feet (3 m) thick walls. In 1242, Henry III sent troops to the island. They scaled the island's cliff and captured William de Marisco and 16 of his "subjects". Henry III built the castle (sometimes erroneously referred to as the Marisco Castle) in an attempt to establish the rule of law on the island and its surrounding waters.

s – including other members of the Marisco family – took control of the island for short periods. Ships were forced to navigate close to Lundy because of the dangerous shingle banks in the fast flowing River Severn

and Bristol Channel

, with its 32 feet (10 m) tide, the second highest in the world. This made the island a profitable location from which to prey on passing Bristol-bound

merchant ships bringing back valuable goods from overseas.

In 1627 Barbary Pirates from the Republic of Salé

occupied Lundy for five years. The North African invaders, under the command of Dutch renegade Jan Janszoon

, flew an Ottoman

flag over the island. Some captured Europeans were held on Lundy before being sent to Algiers as slaves. From 1628 to 1634 the island was plagued by pirate ships of French, Basque, English, and Spanish origin. These incursions were eventually ended by Sir John Pennington, but in the 1660s and as late as the 1700s the island still fell prey to French privateers.

, Thomas Bushell

held Lundy for King Charles I

, rebuilding Marisco Castle and garrisoning the island at his own expense. He was a friend of Francis Bacon

, a strong supporter of the Royalist

cause and an expert on mining and coining. It was the last Royalist territory held between the first

and second

civil wars. After receiving permission from Charles I, Bushell surrendered the island on 24 February 1647 to Richard Fiennes, representing General Fairfax. In 1656, the island was acquired by Lord Saye and Sele

.

for Barnstaple in 1747 and Sheriff of Devon

, who notoriously used the island for housing convicts whom he was supposed to be deporting. Benson leased Lundy from its owner, Lord Gower, at a rent of £60 per annum and contracted with the Government to transport a shipload of convicts to Virginia

, but diverted the ship to Lundy to use the convicts as his personal slaves. Later Benson was involved in an insurance swindle. He purchased and insured the ship Nightingale and loaded it with a valuable cargo of pewter and linen. Having cleared the port on the mainland, the ship put into Lundy, where the cargo was removed and stored in a cave built by the convicts, before setting sail again. Some days afterwards, when a homeward-bound vessel was sighted, the Nightingale was set on fire and scuttled. The crew were taken off the stricken ship by the other ship, which landed them safely at Clovelly.

Sir Aubrey Vere Hunt of Curragh Chase purchased the island from John Cleveland in 1802 for £5,270. Sir Vere Hunt planted in the island a small, self-contained Irish colony with its

own constitution and divorce laws, coinage and stamps. He failed in his attempt to sell the Island to the British Government as a base for troops, and his son Sir Aubrey Thomas De Vere

also had great difficult in securing any profit from the property. The tenants came from Sir Vere Hunt's Irish estate and they experienced agricultural difficulties while on the island. This led Sir Vere Hunt to seek someone who would take the island off his hands. In the 1820s John Benison agreed to purchase the Island for £4,500 but then refused to complete sale as he felt that that Aubrey could not make out a good title in respect of the sale terms, namely that the Island was free from tithes and taxes.

Foundations for the first lighthouse were laid in 1787 but the lighthouse was not built until Trinity House

obtained a 999-year lease in 1819. The 97 feet (30 m) tower, on the summit of Chapel Hill, was designed by Daniel Asher Alexander

and built by Joseph Nelson at a cost of £36,000. Because the site is 407 feet (124 m) above sea level, the highest base for a lighthouse in Britain, the fog problem was not solved and the Fog Signal Battery was built about 1861. The lighthouse had two lights, however they revolved so quickly that they gave the impression it was a fixed light with no flashes detectable. These may have contributed to the grounding, at Cefn Sidan

, of the La Jeune Emma, bound from Martinique

to Cherbourg in 1828. 13 of the 19 on board drowned, including Adeline Coquelin, the 12 year-old niece of Napoleon Bonaparte's divorced wife Josephine de Beauharnais. Eventually the lighthouse was abandoned in 1897 when the North and South Lundy lighthouses were built. The Old Light and the associated keeper's houses are kept open by the Landmark Trust

.

William Hudson Heaven purchased Lundy in 1834, as a summer retreat and for the shooting

, at a cost of 9,400 guineas

(£9,870). He claimed it to be a "free island", and successfully resisted the jurisdiction of the mainland magistrates. Lundy was in consequence sometimes referred to as "the kingdom of Heaven". It belongs in fact to the county of Devon, and has always been part of the hundred of Braunton

. Many of the buildings on the island today, including St. Helena's Church and Millcombe House (originally known simply as The Villa), date from the Heaven period. The Georgian-style

Villa was built in 1836. However, the expense of building the road from the beach (no financial assistance being provided by Trinity House

, despite their regular use of the road following the construction of the lighthouses), the Villa and the general cost of running the island had a ruinous effect on the family's finances, which had been damaged by reduced profits from their sugar plantations in Jamaica

.

In 1957 a message in a bottle from one of the seamen of the HMS Caledonia

was washed ashore between Babbacombe

and Peppercombe in Devon

. The letter, dated August 15, 1843 read: "Dear Brother, Please e God i be with y against Michaelmas. Prepare y search Lundy for y Jenny ivories. Adiue William, Odessa". The bottle and letter are on display at the Portledge Hotel at Fairy Cross, in Devon, England. The Jenny was a three-masted schooner

reputed to be carrying ivory and gold dust that was wrecked on Lundy (at a place thereafter called Jenny's Cove) on February 20, 1797. The ivory was apparently recovered some years later but the leather bags supposed to contain gold dust were never found.

The north lighthouse is 17 metres tall—slightly taller than the south one; they are painted white and were automated in 1991 and 1994. The south lighthouse has a focal length

of 53 metres (173.9 ft) and a quick white flash every 15 seconds. It can be seen as a small white dot from Hartland Point

, 11 miles to the south east. It was automated and converted to solar power

in 1994. Both lighthouses are run and maintained by Trinity House

. The northern light, which has a focal plane of 48 metres (157.5 ft) and produces a quick white flash every 5 seconds, was originally lit by a 75mm petroleum vapour burner and oil was lifted up from a small quay using a sled and winch, and then transported using a small railway (again winch-powered). The remains of this can be still seen, but it was abandoned in 1971 and the lighthouses use a discharge bulb fed from the island's main supply. In 1985 the northern light was modernised six years later and was converted to solar power.

a Grade II listed building. He is said to have been able to afford either a church or a new harbour. His choice of the church was not however in the best financial interests of the island. The unavailability of the money for re-establishing the family's financial soundness, coupled with disastrous investment and speculation in the early 20th century, caused severe financial hardship.

Hudson Heaven died in 1916, and was succeeded by his nephew, Walter Charles Hudson Heaven. With the outbreak of World War I

Hudson Heaven died in 1916, and was succeeded by his nephew, Walter Charles Hudson Heaven. With the outbreak of World War I

, matters deteriorated seriously, and in 1918 the family sold Lundy to Augustus Langham Christie. In 1924, the Christie family sold the island along with the mail contract and the MV

Lerina to Martin Coles Harman, who proclaimed himself a king. Harman issued two coins of Half Puffin and One Puffin denominations in 1929, nominally equivalent to the British halfpenny and penny, resulting in his prosecution under the United Kingdom

's Coinage Act of 1870

. The House of Lords

found him guilty in 1931, and he was fined £5 with fifteen guineas expenses. The coins were withdrawn and became collectors' items. In 1965 a "fantasy" restrike four-coin set, a few in gold, was issued to commemorate 40 years since Harman purchased the island. Harman's son, John Pennington Harman

was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross

in Kohima

, India

in 1944. There is a memorial to him at the VC Quarry on Lundy. Martin Coles Harman died in 1954.

Residents did not pay taxes to the United Kingdom and had to pass through customs when they travelled to and from Lundy Island. Although the island was ruled as a virtual fiefdom

, its owner never claimed to be independent of the United Kingdom, in contrast to later territorial "micronation

s".

Following the death of Harman's son Albion in 1968, Lundy was put up for sale in 1969. Jack Hayward

, a British millionaire, purchased the island for £150,000 and gave it to the National Trust

, who leased it to the Landmark Trust

. The Landmark Trust has managed the island since then, deriving its income from arranging day trips, letting out holiday cottages and from donations.

The island is visited by over 20,000 day-trippers a year, but during September 2007 had to be closed for several weeks owing to an outbreak of Norovirus.

_aground_lundy_island_1906.jpg) A naval footnote in the history of Lundy was the wreck of the Royal Navy battleship HMS Montagu

A naval footnote in the history of Lundy was the wreck of the Royal Navy battleship HMS Montagu

. Steaming in heavy fog, she ran hard aground near Shutter Rock on the island's southwest corner at about 2:00 a.m. on May 30, 1906. Thinking they were aground at Hartland Point

on the English mainland, a landing party went ashore for help, only finding out where they were after encountering the lighthouse

keeper at the island's north light.

_heavy_fittings_removed_1906.jpg) Strenuous efforts by the Royal Navy

Strenuous efforts by the Royal Navy

to salvage the badly damaged battleship during the summer of 1906 failed, and in 1907 it was decided to give up and sell her for scrap. Montagu was scrapped at the scene over the next fifteen years. Diving clubs still visit the site, where armour plate and live 12-inch (305-millimetre) shells remain on the seabed.

two German Heinkel He 111

bombers crash landed on the island in 1941. The first was on 3 March, when all the crew survived and were taken prisoner. The second was on 1 April when the pilot was killed and the other crew members were taken prisoner. The plane had bombed a British ship and one engine damaged by anti aircraft

fire, forcing it to crash land. A few remains can be found on the crash site. Reportedly to avoid reprisals the crew concocted a story that they were on a reconnaissance mission.

Lundy is located at 51°10′37.8876"N 4°39′57.96"W (51.177191, 4.6661). It is 3 miles (5 km) long from north to south by about 0.75 miles (1.2 km) wide, with an area of 445 hectares (1.72 sq mi). The highest point on Lundy is at 142 metres (465.9 ft). A few metres off the northeastern coast is Seal's Rock which is so called after the seals

Lundy is located at 51°10′37.8876"N 4°39′57.96"W (51.177191, 4.6661). It is 3 miles (5 km) long from north to south by about 0.75 miles (1.2 km) wide, with an area of 445 hectares (1.72 sq mi). The highest point on Lundy is at 142 metres (465.9 ft). A few metres off the northeastern coast is Seal's Rock which is so called after the seals

which rest on and inhabit the islet

. It is less than 50 metre wide.

of 50±3 to 54±2 million years (from the Eocene

period), with slate

at the southern end; the plateau soil is mainly loam

, with some peat

. Among the igneous dykes

cutting the granite are a small number composed of a unique orthophyre

. This was given the name Lundyite in 1914, although the term – never precisely defined – has since fallen into disuse.

There is one endemic plant species, the Lundy Cabbage

There is one endemic plant species, the Lundy Cabbage

(Coincya wrightii), a species of primitive brassica

.

By the 1980s the eastern side of the island had become overgrown by rhododendron

s (Rhododendron ponticum) which had spread from a few specimens planted in the garden of Millcombe House in Victorian times, but eradication of this non-native plant has been undertaken by volunteers over the past fifteen years in an operation known on the island as "rhody-bashing", which it is hoped will be completed by 2012. The vegetation on the plateau is mainly dry heath, with an area of waved Calluna

heath towards the northern end of the island, which is also rich in lichens, such as Teloschistes flavicans and several species of Cladonia

and Parmelia

. Other areas are either a dry heath/acidic grassland mosaic, characterised by heaths and Western Gorse (Ulex gallii), or semi-improved acidic grassland in which Yorkshire Fog

(Holcus lanatus) is abundant. Tussocky (Thrift) (Holcus/Armeria) communities occur mainly on the western side, and some patches of Bracken

(Pteridium aquilinum) on the eastern side.

. The beetles are now known not to be unique to Lundy, but an endemic weevil

, the Lundy cabbage flea beetle, (Psylliodes luridipennis) has been discovered. The island is also home to the purseweb spider (Atypus affinis), the only British member of the bird-eating spider family.

(Fratercula arctica), which may have given the island its name, declined in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, with the 2005 breeding population estimated to be only two or three pairs, as a consequence of depredations by brown and black rats

(Rattus rattus) (which have now been eliminated) and possibly also as a result of commercial fishing for sand eel

s, the puffins' principal prey. Since 2005, the breeding numbers have been slowly increasing. Adults were seen taking fish into four burrows in 2007, and six burrows in 2008.

As an isolated island on major migration routes, Lundy has a rich bird life and is a popular site for birding. Large numbers of Black-legged Kittiwake

As an isolated island on major migration routes, Lundy has a rich bird life and is a popular site for birding. Large numbers of Black-legged Kittiwake

(Rissa tridactyla) nest on the cliffs, as do Razorbill

(Alca torda), Guillemot

(Uria aalge), Herring Gull (Larus argentatus), Lesser Black-backed Gull

(Larus fuscus), Fulmar

(Fulmarus glacialis), Shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis), Oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus), Skylark

(Alauda arvensis), Meadow pipit

(Anthus pratensis), Common Blackbird (Turdus merula), Robin

(Erithacus rubecula) and Linnet

(Carduelis cannabina). There are also smaller populations of Peregrine Falcon

(Falco peregrinus) and Raven

(Corvus corax).

Lundy has attracted many vagrant birds, in particular species from North America. The island's bird list totals 317 species. This has included the following species, each of which represents the sole British record: Ancient Murrelet

, Eastern Phoebe

and Eastern Towhee

. Records of Bimaculated Lark

, American Robin

and Common Yellowthroat

were also firsts for Britain (American Robin has also occurred two further times on Lundy). Veery

s in 1987 and 1997 were Britain's second and fourth records, a Rüppell's Warbler

in 1979 was Britain's second, an Eastern Bonelli's Warbler

in 2004 was Britain's fourth, and a Black-faced Bunting

in 2001 Britain's third.

Other British Birds rarities

that have been sighted (single records unless otherwise indicated) are: Little Bittern

, Glossy Ibis

, Gyrfalcon

(3 records), Little

and Baillon's

crakes, Collared Pratincole

, Semipalmated

(5 records), Least

(2 records), White-rumped

and Baird's

(2 records) sandpipers, Wilson's Phalarope

, Laughing Gull

, Bridled Tern

, Pallas's Sandgrouse

, Great Spotted

, Black-billed

and Yellow-billed

(3 records) cuckoos, European Roller

, Olive-backed Pipit

, Citrine Wagtail

, Alpine Accentor

, Thrush Nightingale

, Red-flanked Bluetail

, Black-eared

(2 records) and Desert

wheatears, White's

, Swainson's

(3 records), and Grey-cheeked (2 records) thrushes, Sardinian

(2 records), Arctic

(3 records), Radde's

and Western Bonelli's

warblers, Isabelline

and Lesser Grey

shrikes, Red-eyed Vireo

(7 records), Two-barred Crossbill

, Yellow-rumped

and Blackpoll

warblers, Yellow-breasted

(2 records) and Black-headed

(3 records) buntings, Rose-breasted Grosbeak

(2 records), Bobolink

and Baltimore Oriole

(2 records).

Lundy is home to an unusual range of mammals, almost all introduced, including a distinct breed of wild pony, the Lundy Pony

Lundy is home to an unusual range of mammals, almost all introduced, including a distinct breed of wild pony, the Lundy Pony

. Until recently, Lundy and the Shiant Isles

in the Hebrides were the only two places in the UK where the Black Rat

(Rattus rattus) could be found. It has since been eradicated on the island, in order to protect the nesting seabirds. Other species which have made the island their home include the Grey Seal

(Halichoerus grypus), Sika Deer

(Cervus nippon), Pygmy Shrew

(Sorex minutus) and feral goat

s (Capra aegagrus hircus). Unusually, 20% of the rabbits (Leporidae) on the island are melanistic

compared with 4% which is typical in the UK. In mid-2006 the rabbit population was devastated by myxomatosis

, leaving only 60 pairs from the previous 15–20,000 individuals. Soay Sheep

(Ovis aries) on the island have been shown to vary their behaviours according to nutritional requirements, the distribution of food and the risk of predation.

, and on 21 November 1986 the Secretary of State for the Environment

announced the designation of a statutory reserve at Lundy.

There is an outstanding variety of marine habitats and wildlife, and a large number of rare and unusual species in the waters around Lundy, including some species of seaweed

, branching sponges, sea fan

s and cup corals

.

In 2003 the first statutory No Take Zone (NTZ) for marine nature conservation in the UK was set up in the waters to the east of Lundy island. In 2008 this was declared as having been successful in several ways including the increasing size and number of lobsters within the reserve, and potential benefits for other marine wildlife. However, the no take zone has received a mixed reaction from local fishermen.

On 12 January 2010 the island became Britain's first Marine Conservation Zone

designated under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009

, designed to help to preserve important habitats and species.

Two ways exist for getting to Lundy, depending upon the season of travel. During the summer months (April to October) visitors are carried on the Landmark Trust

Two ways exist for getting to Lundy, depending upon the season of travel. During the summer months (April to October) visitors are carried on the Landmark Trust

's own vessel, MS Oldenburg

, which sails from both Bideford and Ilfracombe. Sailings are usually three days a week, on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, with additional sailings on Wednesdays during July and August. The voyage takes on average two hours, depending on ports, tides and weather. The Oldenburg was first registered in Bremen

, Germany in 1958 and has been sailing to Lundy since the replacement of her engine in 1985.

During the winter months (November to March), the Oldenburg comes out of service, and the island is served by a scheduled helicopter

service from Hartland Point

. The helicopter operates on Mondays and Fridays, with flights between 12 noon and 2 pm. The heliport

is a field at the top of Hartland Point, not far from the Beacon.

A grass runway of 400 metres (1,312 ft) by 28 metres (92 ft) is available, allowing access to small STOL aircraft skilfully piloted.

Entrance to Lundy is free for anyone arriving by scheduled transport. Visitors arriving by non-scheduled transport are charged a small entrance fee, currently (July 2007) £5.00, with an additional charge payable by those using light aircraft. Anyone arriving on Lundy by non-scheduled transport is also subject to an additional fee for transporting luggage to the top of the island.

In 2007, Derek Green, Lundy's general manager, launched an appeal to raise £250,000 to save the mile-long Beach Road, which had been damaged by heavy rain and high seas. The road was built in the first half of the 19th century to provide people and goods with safe access to the top of the island, 120 metres (394 ft) above the only jetty. The fund-raising was completed on the 10th March 2009.

B and C series diesel engines, offering an approx 150 kVa 3 phase supply to most of the island buildings. Waste heat from the engine jackets is used for a district heating pipe. (cf. cogeneration

.) There are also plans to collect the waste heat from the engine exhaust heat gases to feed into the district heat network to improve the efficiency further.

The island also has a campsite, at the south of the island in the field next to the shop. It has hot and cold running water, with showers and toilets in an adjacent building.

of Torridge

district of the English

county

of Devon

. It belongs to the ward

of Clovelly Bay

. It is part of the constituency electing the Member of Parliament

for Torridge and West Devon and the South West England constituency for the European Parliament

.

as a "local carriage label". Issues of increasing value were made over the years, including air mail, featuring a variety of people. Many are now highly sought-after by collectors.

Lundy Island continues to issue stamps with the latest issues being in 2008 (50th birthday of MS Oldenburg) and 2010 (Island wildlife). The value of the early issues has risen substantially over the years. The stamps of Lundy Island serve to cover the postage of letters and cards from the island to the nearest GPO post box on the mainland for the many thousands of annual visitors, and have become part of the collection of the many British Local Posts collectors. These stamps appeared in 1970s in the Rosen Catalogue of British Local Stamps, and in the Phillips Modern British Locals CD Catalogue, published since 2003. There is a comprehensive collection of these stamps in the Chinchen Collection, donated by Barry Chinchen to the British Library Philatelic Collections

in 1977 and located at the British Library

. This also the home of the Landmark Trust Lundy Island Philatelic Archive which includes artwork, texts and essays as well as postmarking devices and issued stamps.

Labbe's Specialized Guide to Lundy Island Stamps serves as a definitive guide to the issues of Lundy Island including varieties, rarities and special philatelic items.

Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales from Devon and Somerset in South West England. It extends from the lower estuary of the River Severn to the North Atlantic Ocean...

, lying 12 miles (19 km) off the coast of Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

, England, approximately one third of the distance across the channel between England and Wales. It measures about 3 by at its widest. Lundy gives its name to a British sea area and is one of the islands of England.

As of 2007, there was a resident population of 28 people, including volunteers. These include a warden, ranger, island manager, and farmer, as well as bar and house-keeping staff. Most live in and around the village at the south of the island. Most visitors are day-tripper

Day-tripper

A day-tripper is a person who visits a tourist destination or visitor attraction from his/her home and returns home on the same day.- Definition :In other words, this excursion does not involve a night away from home such as experienced on a holiday...

s, although there are 23 holiday properties and a camp site for staying visitors, mostly also around the south of the island.

In a 2005 opinion poll of Radio Times

Radio Times

Radio Times is a UK weekly television and radio programme listings magazine, owned by the BBC. It has been published since 1923 by BBC Magazines, which also provides an on-line listings service under the same title...

readers, Lundy was named as Britain's tenth greatest natural wonder. The entire island has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest

Site of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom. SSSIs are the basic building block of site-based nature conservation legislation and most other legal nature/geological conservation designations in Great Britain are based upon...

and it was England's first statutory Marine Nature Reserve

Nature reserve

A nature reserve is a protected area of importance for wildlife, flora, fauna or features of geological or other special interest, which is reserved and managed for conservation and to provide special opportunities for study or research...

, and the first Marine Conservation Zone, because of its unique flora and fauna. It is managed by the Landmark Trust

Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British building conservation charity, founded in 1965 by Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or architectural merit and then gives them a new life by making them available for holiday rental...

on behalf of the National Trust

National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, usually known as the National Trust, is a conservation organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland...

.

History

Old Norse

Old Norse is a North Germanic language that was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and inhabitants of their overseas settlements during the Viking Age, until about 1300....

word for a puffin

Puffin

Puffins are any of three small species of auk in the bird genus Fratercula with a brightly coloured beak during the breeding season. These are pelagic seabirds that feed primarily by diving in the water. They breed in large colonies on coastal cliffs or offshore islands, nesting in crevices among...

and ey, an island, although an alternative explanation has been suggested with Lund referring to a copse, or wooded area. According to genealogist Edward MacLysaght

Edward MacLysaght

Edward MacLysaght was one of the foremost genealogists of twentieth century Ireland. His numerous books on Irish surnames built upon the work of Patrick Woulfe's Irish Names and Surnames and made him well known to all those researching their family past.-Early life:Edward was born in Flax Bourton...

the surname Lundy is from Norman de la Lounde, a name recorded in medieval documents in counties Tipperary

Tipperary

Tipperary is a town and a civil parish in South Tipperary in Ireland. Its population was 4,415 at the 2006 census. It is also an ecclesiastical parish in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly, and is in the historical barony of Clanwilliam....

and Kilkenny

Kilkenny

Kilkenny is a city and is the county town of the eponymous County Kilkenny in Ireland. It is situated on both banks of the River Nore in the province of Leinster, in the south-east of Ireland...

in Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

.

Lundy has evidence of visitation or occupation from the Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

period onward, with Mesolithic

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

flintwork, Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

burial mounds

Tumulus

A tumulus is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, Hügelgrab or kurgans, and can be found throughout much of the world. A tumulus composed largely or entirely of stones is usually referred to as a cairn...

, four inscribed gravestones from the early medieval period, and an early medieval monastery (possibly dedicated to St Elen or St Helen).

Beacon Hill Cemetery

Charles Thomas (historian)

Antony Charles Thomas, CBE, FSA is a British historian and archaeologist who was Professor of Cornish Studies at Exeter University, and the first Director of the Institute of Cornish Studies, from 1971 until his retirement in 1991...

in 1969. The cemetery contains four inscribed stones, dated to the 5th or 6th century AD. The site was originally enclosed by a curvilinear bank and ditch, which is still visible in the south west corner. However, the other walls were moved when the Old Light was constructed in 1819. Early Christian enclosures of this type are known as lann

Llan place name element

Llan or Lan is a common place name element in Brythonic languages such as Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Cumbric, and possibly Pictish. In Wales there are over 630 place names beginning with 'Llan', pronounced...

s in Cornish

Cornish language

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language and a recognised minority language of the United Kingdom. Along with Welsh and Breton, it is directly descended from the ancient British language spoken throughout much of Britain before the English language came to dominate...

. There are surviving examples in Luxulyan

Luxulyan

Luxulyan , also spelled Luxullian or Luxulian, is a village and civil parish in central Cornwall, United Kingdom. The village lies four miles northeast of St Austell and six miles south of Bodmin...

, in Cornwall; Mathry

Mathry

Mathry is a village in Pembrokeshire, Wales. Situated some 6 miles west of Fishguard, the village is perched atop a hill.In 2006 in records office in Haverfordwest records were found, which show a Jemima Nicholas being baptised in the parish of Mathry on 2 March 1755.Nearby villages include...

, Mydrim, and Clydey in Wales; and Stowford, Jacobstowe

Jacobstowe

Jacobstowe is a village and civil parish in the West Devon district of Devon in England. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 118. The village is on the River Okement, about 5 miles north of Okehampton.-Trivia:...

, Lydford

Lydford

Lydford, sometimes spelled Lidford, is a village, once an important town, in Devon situated north of Tavistock on the western fringe of Dartmoor in the West Devon district.-Description:The village has a population of 458....

, and Instow

Instow

Instow is a village in north Devon, England. It is on the estuary where the rivers Taw and Torridge meet, between the villages of Westleigh and Yelland and on the opposite bank of Appledore....

, in Devon.

Thomas proposed a five-stage sequence of site usage:

(1) An area of round huts

Roundhouse (dwelling)

The roundhouse is a type of house with a circular plan, originally built in western Europe before the Roman occupation using walls made either of stone or of wooden posts joined by wattle-and-daub panels and a conical thatched roof. Roundhouses ranged in size from less than 5m in diameter to over 15m...

and fields. These huts may have fallen into disuse before the construction of the cemetery.

(2) The construction of the focal grave, an 11 ft by 8 ft rectangular stone enclosure containing a single cist

Cist

A cist from ) is a small stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. Examples can be found across Europe and in the Middle East....

grave. The interior of the enclosure was filled with small granite pieces. Two more cist graves located to the west of the enclosure may also date from this time.

(3) Perhaps 100 years later, the focal grave was opened and the infill removed. The body may have been moved to a church at this time.

(4) & (5) Two further stages of cist grave construction around the focal grave.

23 cist graves were found during this excavation. Considering that the excavation only uncovered a small area of the cemetery, there may be as many as 100 graves.

Inscribed stones

Celtic inscribed stone

Celtic inscribed stones are stone monuments dating from 400 to 1000 AD. They are inscribed with Celtic or Latin text, which can be written in Ogham or Roman characters. Some stones have both Ogham and Roman inscriptions. The stones are found in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, the Isle of Man,...

s have been found in Beacon Hill cemetery:

- 1400 OPTIMI, or TIMI; the name Optimus is Latin and male. Discovered in 1962 by D. B. Hague.

- 1401 RESTEVTAE, or RESGEVT[A], Latin, female i.e. Resteuta or Resgeuta. Discovered in 1962 by D. B. Hague.

- 1402 POTIT[I], or [PO]TIT, Latin, male. Discovered in 1961 by K. S. Gardener and A. Langham.

- 1403 --]IGERNI [FIL]I TIGERNI, or—I]GERNI [FILI] [T]I[G]ERNI, Brittonic, male i.e. Tigernus son of Tigernus. Discovered in 1905.

Knights Templar

Lundy was granted to the Knights TemplarKnights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon , commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders...

by Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

in 1160. The Templars were a major international maritime force at this time, with interests in North Devon, and almost certainly an important port at Bideford

Bideford

Bideford is a small port town on the estuary of the River Torridge in north Devon, south-west England. It is also the main town of the Torridge local government district.-History:...

or on the River Taw

River Taw

The River Taw rises at Taw Head, a spring on the central northern flanks of Dartmoor. It reaches the Bristol Channel away on the north coast of Devon at a joint estuary mouth which it shares with the River Torridge.-Watercourse:...

in Barnstaple

Barnstaple

Barnstaple is a town and civil parish in the local government district of North Devon in the county of Devon, England, UK. It lies west southwest of Bristol, north of Plymouth and northwest of the county town of Exeter. The old spelling Barnstable is now obsolete.It is the main town of the...

. This was probably because of the increasing threat posed by the Norse

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

sea raiders; however, it is unclear whether they ever took possession of the island. Ownership was disputed by the Marisco family who may have already been on the island during King Stephen

Stephen of England

Stephen , often referred to as Stephen of Blois , was a grandson of William the Conqueror. He was King of England from 1135 to his death, and also the Count of Boulogne by right of his wife. Stephen's reign was marked by the Anarchy, a civil war with his cousin and rival, the Empress Matilda...

's reign. The Mariscos were fined, and the island was cut off from necessary supplies. Evidence of the Templars' weak hold on the island came when King John

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

, on his accession in 1199, confirmed the earlier grant.

Marisco family

Henry III of England

Henry III was the son and successor of John as King of England, reigning for 56 years from 1216 until his death. His contemporaries knew him as Henry of Winchester. He was the first child king in England since the reign of Æthelred the Unready...

. Three years later, an attempt was made to kill Henry III by a man who later confessed to being an agent of the Marisco family. William de Marisco fled to Lundy where he lived as a virtual king. He built a stronghold in the area now known as Bulls' Paradise with 9 feet (3 m) thick walls. In 1242, Henry III sent troops to the island. They scaled the island's cliff and captured William de Marisco and 16 of his "subjects". Henry III built the castle (sometimes erroneously referred to as the Marisco Castle) in an attempt to establish the rule of law on the island and its surrounding waters.

Piracy

But the island was hard to govern. Over the next few centuries, trouble followed as both English and foreign pirates and privateerPrivateer

A privateer is a private person or ship authorized by a government by letters of marque to attack foreign shipping during wartime. Privateering was a way of mobilizing armed ships and sailors without having to spend public money or commit naval officers...

s – including other members of the Marisco family – took control of the island for short periods. Ships were forced to navigate close to Lundy because of the dangerous shingle banks in the fast flowing River Severn

River Severn

The River Severn is the longest river in Great Britain, at about , but the second longest on the British Isles, behind the River Shannon. It rises at an altitude of on Plynlimon, Ceredigion near Llanidloes, Powys, in the Cambrian Mountains of mid Wales...

and Bristol Channel

Bristol Channel

The Bristol Channel is a major inlet in the island of Great Britain, separating South Wales from Devon and Somerset in South West England. It extends from the lower estuary of the River Severn to the North Atlantic Ocean...

, with its 32 feet (10 m) tide, the second highest in the world. This made the island a profitable location from which to prey on passing Bristol-bound

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

merchant ships bringing back valuable goods from overseas.

In 1627 Barbary Pirates from the Republic of Salé

Republic of Salé

The Republic of Salé was an independent corsair city-state on the Moroccan coast. It was a major piratical port during its brief existence in the 17th century.-History:-History:...

occupied Lundy for five years. The North African invaders, under the command of Dutch renegade Jan Janszoon

Jan Janszoon

Jan Janszoon van Haarlem, commonly known as Murat Reis the younger was the first President and Grand Admiral of the Corsair Republic of Salé, Governor of Oualidia, and a Dutch pirate, one of the most notorious of the Barbary pirates from the 17th century; the most famous of the "Salé...

, flew an Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

flag over the island. Some captured Europeans were held on Lundy before being sent to Algiers as slaves. From 1628 to 1634 the island was plagued by pirate ships of French, Basque, English, and Spanish origin. These incursions were eventually ended by Sir John Pennington, but in the 1660s and as late as the 1700s the island still fell prey to French privateers.

Civil war

In the English Civil WarEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, Thomas Bushell

Thomas Bushell (mining engineer)

Thomas Bushell was a servant of Francis Bacon who went on to become a mining engineer and defender of Lundy Island for the Royalist cause during the Civil War....

held Lundy for King Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, rebuilding Marisco Castle and garrisoning the island at his own expense. He was a friend of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

, a strong supporter of the Royalist

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

cause and an expert on mining and coining. It was the last Royalist territory held between the first

First English Civil War

The First English Civil War began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War . "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War and...

and second

Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War was the second of three wars known as the English Civil War which refers to the series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1652 and also include the First English Civil War and the...

civil wars. After receiving permission from Charles I, Bushell surrendered the island on 24 February 1647 to Richard Fiennes, representing General Fairfax. In 1656, the island was acquired by Lord Saye and Sele

William Fiennes, 1st Viscount Saye and Sele

William Fiennes, 1st Viscount Saye and Sele was born at the family home of Broughton Castle near Banbury, in Oxfordshire. He was the only son of Richard Fiennes, seventh Baron Saye and Sele...

.

18th and 19th centuries

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were years of lawlessness on Lundy, particularly during the ownership of Thomas Benson, a Member of ParliamentMember of Parliament

A Member of Parliament is a representative of the voters to a :parliament. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, the term applies specifically to members of the lower house, as upper houses often have a different title, such as senate, and thus also have different titles for its members,...

for Barnstaple in 1747 and Sheriff of Devon

High Sheriff of Devon

The High Sheriff of Devon is the Queen's representative for the County of Devon, a territory known as his bailiwick. Selected from three nominated people, he holds his office over the duration of a year. He has judicial, ceremonial and administrative functions and executes High Court...

, who notoriously used the island for housing convicts whom he was supposed to be deporting. Benson leased Lundy from its owner, Lord Gower, at a rent of £60 per annum and contracted with the Government to transport a shipload of convicts to Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

, but diverted the ship to Lundy to use the convicts as his personal slaves. Later Benson was involved in an insurance swindle. He purchased and insured the ship Nightingale and loaded it with a valuable cargo of pewter and linen. Having cleared the port on the mainland, the ship put into Lundy, where the cargo was removed and stored in a cave built by the convicts, before setting sail again. Some days afterwards, when a homeward-bound vessel was sighted, the Nightingale was set on fire and scuttled. The crew were taken off the stricken ship by the other ship, which landed them safely at Clovelly.

Sir Aubrey Vere Hunt of Curragh Chase purchased the island from John Cleveland in 1802 for £5,270. Sir Vere Hunt planted in the island a small, self-contained Irish colony with its

own constitution and divorce laws, coinage and stamps. He failed in his attempt to sell the Island to the British Government as a base for troops, and his son Sir Aubrey Thomas De Vere

Aubrey Thomas de Vere

Aubrey Thomas de Vere was an Irish poet and critic.-Life:He was born at Curraghchase_Forest_Park, Kilcornan, County Limerick, the third son of Sir Aubrey de Vere Hunt and younger brother to Stephen De Vere. In 1832 his father dropped the final name by royal licence. Sir Aubrey was himself a poet...

also had great difficult in securing any profit from the property. The tenants came from Sir Vere Hunt's Irish estate and they experienced agricultural difficulties while on the island. This led Sir Vere Hunt to seek someone who would take the island off his hands. In the 1820s John Benison agreed to purchase the Island for £4,500 but then refused to complete sale as he felt that that Aubrey could not make out a good title in respect of the sale terms, namely that the Island was free from tithes and taxes.

Foundations for the first lighthouse were laid in 1787 but the lighthouse was not built until Trinity House

Trinity House

The Corporation of Trinity House of Deptford Strond is the official General Lighthouse Authority for England, Wales and other British territorial waters...

obtained a 999-year lease in 1819. The 97 feet (30 m) tower, on the summit of Chapel Hill, was designed by Daniel Asher Alexander

Daniel Asher Alexander

Daniel Asher Alexander was a British architect and engineer, born in London.-Life:Daniel Asher Alexander was educated at St Paul's School, London, and admitted to the Royal Academy Schools in 1782....

and built by Joseph Nelson at a cost of £36,000. Because the site is 407 feet (124 m) above sea level, the highest base for a lighthouse in Britain, the fog problem was not solved and the Fog Signal Battery was built about 1861. The lighthouse had two lights, however they revolved so quickly that they gave the impression it was a fixed light with no flashes detectable. These may have contributed to the grounding, at Cefn Sidan

Cefn Sidan

Cefn Sidan, roughly translated from Welsh, means "Silky Back". This long sandy beach and its dunes form the outer edge of the Pembrey Burrows between Burry Port and Kidwelly, looking southwards over Carmarthen Bay in South Wales....

, of the La Jeune Emma, bound from Martinique

Martinique

Martinique is an island in the eastern Caribbean Sea, with a land area of . Like Guadeloupe, it is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. To the northwest lies Dominica, to the south St Lucia, and to the southeast Barbados...

to Cherbourg in 1828. 13 of the 19 on board drowned, including Adeline Coquelin, the 12 year-old niece of Napoleon Bonaparte's divorced wife Josephine de Beauharnais. Eventually the lighthouse was abandoned in 1897 when the North and South Lundy lighthouses were built. The Old Light and the associated keeper's houses are kept open by the Landmark Trust

Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British building conservation charity, founded in 1965 by Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or architectural merit and then gives them a new life by making them available for holiday rental...

.

William Hudson Heaven purchased Lundy in 1834, as a summer retreat and for the shooting

Game (food)

Game is any animal hunted for food or not normally domesticated. Game animals are also hunted for sport.The type and range of animals hunted for food varies in different parts of the world. This will be influenced by climate, animal diversity, local taste and locally accepted view about what can or...

, at a cost of 9,400 guineas

Guinea (British coin)

The guinea is a coin that was minted in the Kingdom of England and later in the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United Kingdom between 1663 and 1813...

(£9,870). He claimed it to be a "free island", and successfully resisted the jurisdiction of the mainland magistrates. Lundy was in consequence sometimes referred to as "the kingdom of Heaven". It belongs in fact to the county of Devon, and has always been part of the hundred of Braunton

Braunton

Braunton is situated west of Barnstaple, Devon, England and is claimed to be the largest village in England, with a population in 2001 of 7,510. It is home to the nearby Braunton Great Field and Braunton Burrows, a National Nature and UNESCO Biosphere Reserve....

. Many of the buildings on the island today, including St. Helena's Church and Millcombe House (originally known simply as The Villa), date from the Heaven period. The Georgian-style

Georgian architecture

Georgian architecture is the name given in most English-speaking countries to the set of architectural styles current between 1720 and 1840. It is eponymous for the first four British monarchs of the House of Hanover—George I of Great Britain, George II of Great Britain, George III of the United...

Villa was built in 1836. However, the expense of building the road from the beach (no financial assistance being provided by Trinity House

Trinity House

The Corporation of Trinity House of Deptford Strond is the official General Lighthouse Authority for England, Wales and other British territorial waters...

, despite their regular use of the road following the construction of the lighthouses), the Villa and the general cost of running the island had a ruinous effect on the family's finances, which had been damaged by reduced profits from their sugar plantations in Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

.

In 1957 a message in a bottle from one of the seamen of the HMS Caledonia

HMS Caledonia

Five ships and three shore establishments of the Royal Navy have borne the name HMS Caledonia after the Latin name for Scotland:Ships was a 3-gun brig launched in 1807. She was captured by the Americans in 1812, and burnt several days later. was a 120-gun first rate ship of the line launched in 1808...

was washed ashore between Babbacombe

Babbacombe

"Babbacombe" may also refer to John 'Babbacombe' LeeBabbacombe is a district of Torquay, Devon, England. It is notable for Babbacombe Model Village, and its clifftop green, Babbacombe Downs, from which Oddicombe Beach is accessed via Babbacombe Cliff Railway.There is a miniature village in the area....

and Peppercombe in Devon

Devon

Devon is a large county in southwestern England. The county is sometimes referred to as Devonshire, although the term is rarely used inside the county itself as the county has never been officially "shired", it often indicates a traditional or historical context.The county shares borders with...

. The letter, dated August 15, 1843 read: "Dear Brother, Please e God i be with y against Michaelmas. Prepare y search Lundy for y Jenny ivories. Adiue William, Odessa". The bottle and letter are on display at the Portledge Hotel at Fairy Cross, in Devon, England. The Jenny was a three-masted schooner

Schooner

A schooner is a type of sailing vessel characterized by the use of fore-and-aft sails on two or more masts with the forward mast being no taller than the rear masts....

reputed to be carrying ivory and gold dust that was wrecked on Lundy (at a place thereafter called Jenny's Cove) on February 20, 1797. The ivory was apparently recovered some years later but the leather bags supposed to contain gold dust were never found.

Lighthouses

The north and south lighthouses were built in 1897, to take over from the old lighthouse.The north lighthouse is 17 metres tall—slightly taller than the south one; they are painted white and were automated in 1991 and 1994. The south lighthouse has a focal length

Focal length

The focal length of an optical system is a measure of how strongly the system converges or diverges light. For an optical system in air, it is the distance over which initially collimated rays are brought to a focus...

of 53 metres (173.9 ft) and a quick white flash every 15 seconds. It can be seen as a small white dot from Hartland Point

Hartland Point

Hartland Point is a high rocky outcrop of land on the northwestern tip of the Devon coast in England. It is three miles north-west of the village of Hartland. The point marks the western limit of the Bristol Channel with the Atlantic Ocean continuing to the west...

, 11 miles to the south east. It was automated and converted to solar power

Solar power

Solar energy, radiant light and heat from the sun, has been harnessed by humans since ancient times using a range of ever-evolving technologies. Solar radiation, along with secondary solar-powered resources such as wind and wave power, hydroelectricity and biomass, account for most of the available...

in 1994. Both lighthouses are run and maintained by Trinity House

Trinity House

The Corporation of Trinity House of Deptford Strond is the official General Lighthouse Authority for England, Wales and other British territorial waters...

. The northern light, which has a focal plane of 48 metres (157.5 ft) and produces a quick white flash every 5 seconds, was originally lit by a 75mm petroleum vapour burner and oil was lifted up from a small quay using a sled and winch, and then transported using a small railway (again winch-powered). The remains of this can be still seen, but it was abandoned in 1971 and the lighthouses use a discharge bulb fed from the island's main supply. In 1985 the northern light was modernised six years later and was converted to solar power.

20th and 21st centuries

William Heaven was succeeded by his son the Reverend Hudson Grosset Heaven who, thanks to a legacy from Sarah Langworthy (née Heaven), was able to fulfill his life's ambition of building a stone church on the island. St Helena's was completed in 1896, and stands today as a lasting memorial to the Heaven period. It has been designated by English HeritageEnglish Heritage

English Heritage . is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport...

a Grade II listed building. He is said to have been able to afford either a church or a new harbour. His choice of the church was not however in the best financial interests of the island. The unavailability of the money for re-establishing the family's financial soundness, coupled with disastrous investment and speculation in the early 20th century, caused severe financial hardship.

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, matters deteriorated seriously, and in 1918 the family sold Lundy to Augustus Langham Christie. In 1924, the Christie family sold the island along with the mail contract and the MV

Merchant vessel

A merchant vessel is a ship that transports cargo or passengers. The closely related term commercial vessel is defined by the United States Coast Guard as any vessel engaged in commercial trade or that carries passengers for hire...

Lerina to Martin Coles Harman, who proclaimed himself a king. Harman issued two coins of Half Puffin and One Puffin denominations in 1929, nominally equivalent to the British halfpenny and penny, resulting in his prosecution under the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

's Coinage Act of 1870

Coinage Act 1870

The Coinage Act 1870 stated the metric weights of British coins. For example, it defined the weight of the sovereign as 7.98805 grams...

. The House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

found him guilty in 1931, and he was fined £5 with fifteen guineas expenses. The coins were withdrawn and became collectors' items. In 1965 a "fantasy" restrike four-coin set, a few in gold, was issued to commemorate 40 years since Harman purchased the island. Harman's son, John Pennington Harman

John Pennington Harman

John Pennington Harman VC was an English recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.-Details:...

was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross

Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross is the highest military decoration awarded for valour "in the face of the enemy" to members of the armed forces of various Commonwealth countries, and previous British Empire territories....

in Kohima

Kohima

Kohima is the hilly capital of India's north eastern border state of Nagaland which shares its borders with Burma. It lies in Kohima District and is also one of the three Nagaland towns with Municipal council status along with Dimapur and Mokokchung....

, India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

in 1944. There is a memorial to him at the VC Quarry on Lundy. Martin Coles Harman died in 1954.

Residents did not pay taxes to the United Kingdom and had to pass through customs when they travelled to and from Lundy Island. Although the island was ruled as a virtual fiefdom

Fiefdom

A fee was the central element of feudalism and consisted of heritable lands granted under one of several varieties of feudal tenure by an overlord to a vassal who held it in fealty in return for a form of feudal allegiance and service, usually given by the...

, its owner never claimed to be independent of the United Kingdom, in contrast to later territorial "micronation

Micronation

Micronations, sometimes also referred to as model countries and new country projects, are entities that claim to be independent nations or states but which are not recognized by world governments or major international organizations...

s".

Following the death of Harman's son Albion in 1968, Lundy was put up for sale in 1969. Jack Hayward

Jack Hayward

Sir Jack Arnold Hayward, OBE is an English businessman, property developer, philanthropist and president of Premier League football club Wolverhampton Wanderers.-Biography:...

, a British millionaire, purchased the island for £150,000 and gave it to the National Trust

National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, usually known as the National Trust, is a conservation organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland...

, who leased it to the Landmark Trust

Landmark Trust

The Landmark Trust is a British building conservation charity, founded in 1965 by Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or architectural merit and then gives them a new life by making them available for holiday rental...

. The Landmark Trust has managed the island since then, deriving its income from arranging day trips, letting out holiday cottages and from donations.

The island is visited by over 20,000 day-trippers a year, but during September 2007 had to be closed for several weeks owing to an outbreak of Norovirus.

Wreck of Battleship Montagu

_aground_lundy_island_1906.jpg)

HMS Montagu (1901)

HMS Montagu was a Pre-dreadnought battleship of the British Royal Navy.In May 1906 in thick fog, she was wrecked on Lundy Island, fortunately without loss of life....

. Steaming in heavy fog, she ran hard aground near Shutter Rock on the island's southwest corner at about 2:00 a.m. on May 30, 1906. Thinking they were aground at Hartland Point

Hartland Point

Hartland Point is a high rocky outcrop of land on the northwestern tip of the Devon coast in England. It is three miles north-west of the village of Hartland. The point marks the western limit of the Bristol Channel with the Atlantic Ocean continuing to the west...

on the English mainland, a landing party went ashore for help, only finding out where they were after encountering the lighthouse

Lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses or, in older times, from a fire, and used as an aid to navigation for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways....

keeper at the island's north light.

_heavy_fittings_removed_1906.jpg)

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

to salvage the badly damaged battleship during the summer of 1906 failed, and in 1907 it was decided to give up and sell her for scrap. Montagu was scrapped at the scene over the next fifteen years. Diving clubs still visit the site, where armour plate and live 12-inch (305-millimetre) shells remain on the seabed.

Remains of a German Heinkel 111H bomber

During World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

two German Heinkel He 111

Heinkel He 111

The Heinkel He 111 was a German aircraft designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter in the early 1930s in violation of the Treaty of Versailles. Often described as a "Wolf in sheep's clothing", it masqueraded as a transport aircraft, but its purpose was to provide the Luftwaffe with a fast medium...

bombers crash landed on the island in 1941. The first was on 3 March, when all the crew survived and were taken prisoner. The second was on 1 April when the pilot was killed and the other crew members were taken prisoner. The plane had bombed a British ship and one engine damaged by anti aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare

NATO defines air defence as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action." They include ground and air based weapon systems, associated sensor systems, command and control arrangements and passive measures. It may be to protect naval, ground and air forces...

fire, forcing it to crash land. A few remains can be found on the crash site. Reportedly to avoid reprisals the crew concocted a story that they were on a reconnaissance mission.

Geography

Pinniped

Pinnipeds or fin-footed mammals are a widely distributed and diverse group of semiaquatic marine mammals comprising the families Odobenidae , Otariidae , and Phocidae .-Overview: Pinnipeds are typically sleek-bodied and barrel-shaped...

which rest on and inhabit the islet

Islet

An islet is a very small island.- Types :As suggested by its origin as islette, an Old French diminutive of "isle", use of the term implies small size, but little attention is given to drawing an upper limit on its applicability....

. It is less than 50 metre wide.

Geology

The island is primarily composed of graniteGranite

Granite is a common and widely occurring type of intrusive, felsic, igneous rock. Granite usually has a medium- to coarse-grained texture. Occasionally some individual crystals are larger than the groundmass, in which case the texture is known as porphyritic. A granitic rock with a porphyritic...

of 50±3 to 54±2 million years (from the Eocene

Eocene

The Eocene Epoch, lasting from about 56 to 34 million years ago , is a major division of the geologic timescale and the second epoch of the Paleogene Period in the Cenozoic Era. The Eocene spans the time from the end of the Palaeocene Epoch to the beginning of the Oligocene Epoch. The start of the...

period), with slate

Slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. The result is a foliated rock in which the foliation may not correspond to the original sedimentary layering...

at the southern end; the plateau soil is mainly loam

Loam

Loam is soil composed of sand, silt, and clay in relatively even concentration . Loam soils generally contain more nutrients and humus than sandy soils, have better infiltration and drainage than silty soils, and are easier to till than clay soils...

, with some peat

Peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation matter or histosol. Peat forms in wetland bogs, moors, muskegs, pocosins, mires, and peat swamp forests. Peat is harvested as an important source of fuel in certain parts of the world...

. Among the igneous dykes

Dike (geology)

A dike or dyke in geology is a type of sheet intrusion referring to any geologic body that cuts discordantly across* planar wall rock structures, such as bedding or foliation...

cutting the granite are a small number composed of a unique orthophyre

Trachyte

Trachyte is an igneous volcanic rock with an aphanitic to porphyritic texture. The mineral assemblage consists of essential alkali feldspar; relatively minor plagioclase and quartz or a feldspathoid such as nepheline may also be present....

. This was given the name Lundyite in 1914, although the term – never precisely defined – has since fallen into disuse.

Climate

Lundy Island lies on the borderline where the North Atlantic Ocean and the Bristol Channel meet, so it has quite a mild climate. Lundy has cool, wet winters and mild, wet summers. It is often windy on the coast.Flora

Lundy cabbage

Lundy cabbage is a species of primitive brassicoid, endemic to the island of Lundy off the southwestern coast of Great Britain, where it is sufficiently isolated to have formed its own species, with its endemic insect pollinators. The Lundy cabbage Coincya wrightii grows only on the eastern cliffs...

(Coincya wrightii), a species of primitive brassica

Brassica

Brassica is a genus of plants in the mustard family . The members of the genus may be collectively known either as cabbages, or as mustards...

.

By the 1980s the eastern side of the island had become overgrown by rhododendron

Rhododendron

Rhododendron is a genus of over 1 000 species of woody plants in the heath family, most with showy flowers...

s (Rhododendron ponticum) which had spread from a few specimens planted in the garden of Millcombe House in Victorian times, but eradication of this non-native plant has been undertaken by volunteers over the past fifteen years in an operation known on the island as "rhody-bashing", which it is hoped will be completed by 2012. The vegetation on the plateau is mainly dry heath, with an area of waved Calluna

Calluna

Calluna vulgaris is the sole species in the genus Calluna in the family Ericaceae. It is a low-growing perennial shrub growing to tall, or rarely to and taller, and is found widely in Europe and Asia Minor on acidic soils in open sunny situations and in moderate shade...

heath towards the northern end of the island, which is also rich in lichens, such as Teloschistes flavicans and several species of Cladonia

Cladonia

Cladonia is a genus of moss-like lichens in the family Cladoniaceae. They are the primary food source for reindeer and caribou. Cladonia species are of economic importance to reindeer-herders, such as the Sami in Scandinavia or the Nenets in Russia. Antibiotic compounds are extracted from some...

and Parmelia

Parmelia (lichen)

Parmelia is a large genus of lichenized fungus with a global distribution, extending from the Arctic to the Antarctic continent but concentrated in temperate regions. 125 species have been recorded on the Indian sub-continent...

. Other areas are either a dry heath/acidic grassland mosaic, characterised by heaths and Western Gorse (Ulex gallii), or semi-improved acidic grassland in which Yorkshire Fog

Yorkshire Fog

Yorkshire Fog or Velvet Grass, Holcus lanatus, is a perennial grass in the Poaceae Family. 'Lanatus' is latin for 'wooly' which describes the plant's hairy texture....

(Holcus lanatus) is abundant. Tussocky (Thrift) (Holcus/Armeria) communities occur mainly on the western side, and some patches of Bracken

Bracken

Bracken are several species of large, coarse ferns of the genus Pteridium. Ferns are vascular plants that have alternating generations, large plants that produce spores and small plants that produce sex cells . Brackens are in the family Dennstaedtiaceae, which are noted for their large, highly...

(Pteridium aquilinum) on the eastern side.

Fauna

Until 2006 the Lundy Cabbage was thought to support two endemic species of beetleBeetle

Coleoptera is an order of insects commonly called beetles. The word "coleoptera" is from the Greek , koleos, "sheath"; and , pteron, "wing", thus "sheathed wing". Coleoptera contains more species than any other order, constituting almost 25% of all known life-forms...

. The beetles are now known not to be unique to Lundy, but an endemic weevil

Weevil

A weevil is any beetle from the Curculionoidea superfamily. They are usually small, less than , and herbivorous. There are over 60,000 species in several families, mostly in the family Curculionidae...

, the Lundy cabbage flea beetle, (Psylliodes luridipennis) has been discovered. The island is also home to the purseweb spider (Atypus affinis), the only British member of the bird-eating spider family.

Birds

The number of puffinsAtlantic Puffin

The Atlantic Puffin is a seabird species in the auk family. It is a pelagic bird that feeds primarily by diving for fish, but also eats other sea creatures, such as squid and crustaceans. Its most obvious characteristic during the breeding season is its brightly coloured bill...

(Fratercula arctica), which may have given the island its name, declined in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, with the 2005 breeding population estimated to be only two or three pairs, as a consequence of depredations by brown and black rats

Black Rat