Krill

Encyclopedia

Krill is the common name given to the order

Euphausiacea of shrimp

-like marine crustacean

s. Also known as euphausiids, these small invertebrate

s are found in all oceans of the world. The common name krill comes from the Norwegian

word , meaning "young fry of fish", which is also often attributed to other species of fish.

Krill are considered an important trophic level

connection – near the bottom of the food chain

– because they feed on phytoplankton

and to a lesser extent zooplankton

, converting these into a form suitable for many larger animals for whom krill makes up the largest part of their diet. In the Southern Ocean

, one species, the Antarctic krill

, Euphausia superba, makes up an estimated biomass

of over 500000000 tonnes (492,101,766.6 LT), roughly twice that of humans. Of this, over half is eaten by whales, seals, penguins, squid and fish each year, and is replaced by growth and reproduction. Most krill species display large daily vertical migrations

, thus providing food for predators near the surface at night and in deeper waters during the day.

Commercial fishing of krill is done in the Southern Ocean

and in the waters around Japan. The total global harvest amounts to 150000 – annually, most of this from the Scotia Sea

. Most of the krill catch is used for aquaculture

and aquarium

feeds, as bait

in sport fishing, or in the pharmaceutical industry. In Japan and Russia, krill is also used for human consumption and is known as in Japan.

subphylum

, the Crustacea

. The most familiar and largest group of crustaceans, the class

Malacostraca

, includes the superorder

Eucarida

comprising the three orders, Euphausiacea or krill, Decapoda

(shrimp, lobsters, crabs), and the minuscule Amphionides

.

The order Euphasiacea comprises two families

. The more abundant Euphausiidae contains ten different genera

with a total of 85 species. Of these, the genus Euphausia

is the largest, with 31 species. The lesser known family, the Bentheuphausiidae, has only one species, Bentheuphausia amblyops

, a bathypelagic krill living in deep waters below 1000 metres (3,280.8 ft). It is considered the most primitive living species of all krill.

Well-known species of the Euphausiidae of commercial krill fisheries

include Antarctic krill

(Euphausia superba), Pacific krill

(Euphausia pacifica) and Northern krill

(Meganyctiphanes norvegica).

due to several unique conserved morphological characteristics (autapomorphy

) such as the naked filamentous gills or the thin thoracopods. and by molecular studies.

There have been many theories of the location of the order Euphausiacea, in fact since the first description of Thysanopode tricuspide by Henri Milne-Edwards

in 1830, the similarity of their biramous thoracopods had led zoologists to group euphausiids and Mysidacea in the order of Schizopoda

, which was split by Johan Erik Vesti Boas

in 1883 into two separate orders. Later, William Thomas Calman

(1904) ranked the Mysidacea

in the Peracarida super-order and euphausiids in Eucarida super-order, although even up to the 1930s the order Schizopoda was advocated. It was later also proposed that order Euphausiacea should be grouped with the Penaeidae

(family of prawns) in the Decapoda based on developmental similarities, as noted by Robert Gurney

and Isabella Gordon

. The reason for this debate is that krill share some morphological features of decapods and others of mysids.

Molecular studies have also no been able to unambiguously group them, possibly due to the lack of many key rare species such as Bentheuphausia amblyops in krill and Amphionides reynaudii in Eucarida. One study supports Eucarida monophyly (with basal Mysida), another groups Euphausiacea with Mysida (the Schizopoda), while yet another groups Euphausiacea with Hoplocarida.

n taxa have been thought to be euphausiaceans such as Anthracophausia, Crangopsis

– now assigned to the Aeschronectida

(Hoplocarida) – and Palaeomysis. Consequently the dating of the speciation

events have been estimated by means of molecular clock

methods, which place the last common ancestor of the krill family Euphausiidae (order Euphausiacea minus Bentheuphausia amblyops) to have lived in the Lower Cretaceous

about .

Krill occur worldwide in all oceans, although many individual species have endemic or neritic (i.e., coastal) restricted distributions. Bentheuphausia amblyops

Krill occur worldwide in all oceans, although many individual species have endemic or neritic (i.e., coastal) restricted distributions. Bentheuphausia amblyops

, a bathypelagic

species, has a cosmopolitan distribution

within its deep-sea habitat.

Species of the genus Thysanoessa

occur in both the Atlantic

and Pacific

oceans. The Pacific is home to Euphausia pacifica. Northern krill

occur across the Atlantic from the Mediterranean Sea

northward.

Species with neritic distributions include the four species of the genus Nyctiphanes

. They are highly abundant along the upwelling

regions of the California

, Humboldt

, Benguela

, and Canarias

current system

s. Another species having only neritic distribution is E. crystallorophias, which occurs only along the Antarctic coastline (and thus also is endemic to that region).

Species with endemic distributions include Nyctiphanes capensis, which occurs only in the Benguela current, E. mucronata in the Humboldt current, and the six Euphausia species native to the Southern Ocean.

In the Antarctic, seven species are known, one species of the genus Thysanoessa (T. macrura) and six of the genus Euphausia. The Antarctic krill

(Euphausia superba) commonly lives at depths of as much as 100 m (328.1 ft), whereas ice krill (Euphausia crystallorophias

) have been recorded at a depth of 4000 m (13,123.4 ft), though they commonly live at depths of at most 300–600 m (984.3–1,968.5 ft). Both are found at latitude

s south of 55° S

, with E. crystallorophias dominating south of 74° S

and in regions of pack ice. Other species known in the Southern Ocean

are E. frigida, E. longirostris, E. triacantha and E. vallentini.

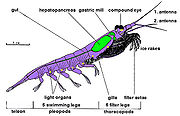

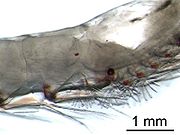

Krill are crustacean

Krill are crustacean

s and have a chitin

ous exoskeleton

made up of three segments: the cephalon (head), the thorax, and the abdomen

. The first two segments are fused into one segment, the cephalothorax

. This outer shell of krill is transparent in most species. Krill feature intricate compound eyes; some species can adapt to different lighting conditions through the use of screening pigment

s. They have two antennae

and several pairs of thoracic legs called pereiopods or thoracopods, so named because they are attached to the thorax; their number varies among genera and species. These thoracic legs include the feeding legs and the grooming legs. Additionally all species have five swimming legs called pleopods or "swimmerets", very similar to those of a lobster or freshwater crayfish. Most krill are about 1–2 cm (0.393700787401575–0.78740157480315 in) long as adults; a few species grow to sizes on the order of 6–15 cm (2.4–5.9 in). The largest krill species is the bathypelagic Thysanopoda spinicauda. Krill can be easily distinguished from other crustaceans such as true shrimp

by their externally visible gill

s.

Many krill are filter feeders: their frontmost appendage

Many krill are filter feeders: their frontmost appendage

s, the thoracopods, form very fine combs with which they can filter out their food from the water. These filters can be very fine indeed in those species (such as Euphausia spp.) that feed primarily on phytoplankton

, in particular on diatom

s, which are unicellular algae

. However, it is believed that krill are mostly omnivorous. A few species are carnivorous, preying on small zooplankton and fish larvae.

Except for Bentheuphausia amblyops, krill are bioluminescent

animals having organs called photophore

s that can emit light. The light is generated by an enzyme-catalysed chemiluminescence reaction, wherein a luciferin

(a kind of pigment

) is activated by a luciferase

enzyme

. Studies indicate that the luciferin of many krill species is a fluorescent

tetrapyrrole

similar but not identical to dinoflagellate

luciferin and that the krill probably do not produce this substance themselves but acquire it as part of their diet, which contains dinoflagellates. Krill photophores are complex organs with lenses and focusing abilities, and they can be rotated by muscles. The precise function of these organs is as yet unknown; they might have a purpose in mating, social interaction or orientation. Some researchers (e.g., Lindsay & Latz and Johnsen) have proposed that krill use the light as a form of counter-illumination camouflage to compensate their shadow against the ambient light from above to make themselves less visible to predators from below.

ing animals; the sizes and densities of such swarms vary greatly depending on the species and the region. For Euphausia superba, there have been reports of swarms of up to 10,000 to 60,000 individuals per cubic metre. Swarming is a defensive mechanism, confusing smaller predators that would like to pick out single individuals. Krill typically follow a diurnal vertical migration

. Until recently it has been assumed that they spend the day at greater depths and rise during the night toward the surface. It has been found that the deeper they go, the more they reduce their activity, apparently to reduce encounters with predators and to conserve energy. Later work suggested that swimming activity in krill varied with stomach fullness. Satiated animals that had been feeding at the surface swim less actively and therefor sink below the mixed layer. As they sink they produce faeces which may mean that they have an important role to play in the Antarctic carbon cycle. Krill with empty stomachs were found to swim more actively and thus head towards the surface. This implies that vertical migration may be a bi or tri daily occurrence. Some species (e.g., Euphausia superba, E. pacifica, E. hanseni, Pseudeuphausia latifrons, and Thysanoessa spinifera) also form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

Dense swarms may elicit a feeding frenzy

Dense swarms may elicit a feeding frenzy

among fish, birds and mammal predators, especially near the surface. When disturbed, a swarm scatters, and some individuals have even been observed to moult

instantaneously, leaving the exuvia

behind as a decoy.

Krill normally swim at pace of 5–10 cm/s (2–3 body lengths per second), using their swimmerets for propulsion. Their larger migrations are subject to the currents in the ocean. When in danger, they show an escape reaction called lobstering

– flicking their caudal structures, the telson

and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second, which for large krill such as E. superba means around 0.8 m/s (3 ft/s). Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as micro-nektonic

life-forms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents. Larval forms of krill are generally considered zooplankton

.

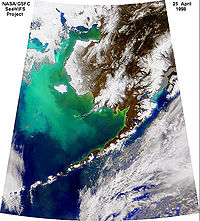

Krill are an important element of the food chain

Krill are an important element of the food chain

. Antarctic krill

feed directly on phytoplankton

, converting the primary production

energy into a form suitable for consumption by larger animals that cannot feed directly on the minuscule algae. Some species like the Northern krill have a relatively small filtering basket and actively hunt for copepod

s and larger zooplankton

. Many animals feed on krill, ranging from smaller animals like fish

or penguin

s to larger ones like seals

and even baleen whale

s.

Disturbances of an ecosystem

resulting in a decline in the krill population can have far-reaching effects. During a coccolithophore

bloom in the Bering Sea

in 1998, for instance, the diatom

concentration dropped in the affected area. Krill cannot feed on the smaller coccolithophores, and consequently the krill population (mainly E. pacifica) in that region declined sharply. This in turn affected other species: the shearwater

population dropped, and the incident was even thought to have been a reason for salmon

not returning to the rivers of western Alaska

that season.

Other factors besides predation and food availability can influence the mortality rate in krill populations. As temperatures have risen over the past couple decades, Antarctic sea ice

has melted. In this way, climate change poses a threat to krill populations as they feed on algae beneath the ice. There are several single-celled endoparasitoidic ciliate

s of the genus Collinia that can infect different species of krill and cause massive decline in affected populations. Such diseases have been reported for Thysanoessa inermis in the Bering Sea and also for E. pacifica, Thysanoessa spinifera, and T. gregaria off the North American Pacific coast. There are also some ectoparasites of the family Dajidae

(epicaridean isopods) that afflict krill (and also shrimp

and mysids); one such parasite is Oculophryxus bicaulis, which has been found on the krill Stylocheiron affine and S. longicorne. It attaches itself to the eyestalk of the animal and sucks blood from its head; it is believed that it inhibits the reproduction of its host, as none of the afflicted animals found reached maturity.

The general life cycle of krill has been the subject of several studies (e.g., Gurney, 1942 and Mauchline & Fisher, 1969) performed on a variety of species and is thus relatively well understood, although there are minor variations in detail from species to species. After krill hatch from the egg, they go through several larval stages called the nauplius, pseudometanauplius, metanauplius

The general life cycle of krill has been the subject of several studies (e.g., Gurney, 1942 and Mauchline & Fisher, 1969) performed on a variety of species and is thus relatively well understood, although there are minor variations in detail from species to species. After krill hatch from the egg, they go through several larval stages called the nauplius, pseudometanauplius, metanauplius

, calyptopsis, and furcilia stages, each of which is sub-divided into several sub-stages. The pseudometanauplius stage is exclusive to species that lay their eggs within an ovigerous sac: so-called "sac-spawners". The larvae grow and moult

multiple times as they develop, shedding their rigid exoskeleton whenever it becomes too small and growing a new one. Smaller animals moult more frequently than larger ones. Up through the metanauplius stage, the larvae are nourished by yolk reserves within their body. Only by the calyptopsis stages has differentiation

progressed far enough for them to develop a mouth and a digestive tract, and they begin to feed upon phytoplankton

. By that time, the larvae must have reached the photic zone

, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish, for their yolk reserves are exhausted by then and they would starve otherwise. During the furcilia stages, segments with pairs of swimmerets are added, beginning at the frontmost segments. Each new pair becomes functional only at the next moult. The number of segments added during any one of the furcilia stages may vary even within one species depending on environmental conditions. After the final furcilia stage, the krill emerges in a shape similar to an adult, but it is still an immature juvenile, that only subsequently develops gonad

s and matures.

During the mating season, which varies depending on the species and the climate, the male deposits a sperm sack

at the genital opening (named thelycum) of the female. The females can carry several thousand eggs in their ovary

, which may then account for as much as one third of the animal's body mass. Krill can have multiple broods in one season, with interbrood periods in the order of days.

There are two types of spawning mechanism. The 57 species of the genera Bentheuphausia, Euphausia, Meganyctiphanes, Thysanoessa, and Thysanopoda are "broadcast spawners": the female releases the fertilised eggs into the water, where they usually sink into deeper waters, disperse, and are on their own. These species generally hatch in the nauplius 1 stage, but have recently been discovered to hatch sometimes as metanauplius or even as calyptopis stages. The remaining 29 species of the other genera are "sac spawners", where the female carries the eggs with her, attached to the rearmost pairs of thoracopods until they hatch as metanauplii, although some species like Nematoscelis difficilis may hatch as nauplius or pseudometanauplius.

There are two types of spawning mechanism. The 57 species of the genera Bentheuphausia, Euphausia, Meganyctiphanes, Thysanoessa, and Thysanopoda are "broadcast spawners": the female releases the fertilised eggs into the water, where they usually sink into deeper waters, disperse, and are on their own. These species generally hatch in the nauplius 1 stage, but have recently been discovered to hatch sometimes as metanauplius or even as calyptopis stages. The remaining 29 species of the other genera are "sac spawners", where the female carries the eggs with her, attached to the rearmost pairs of thoracopods until they hatch as metanauplii, although some species like Nematoscelis difficilis may hatch as nauplius or pseudometanauplius.

Some high-latitude species of krill can live for more than six years (e.g., Euphausia superba); others, such as the mid-latitude species Euphausia pacifica, live for only two years. Subtropical or tropical

species' longevity is still shorter, e.g., Nyctiphanes simplex, which usually lives for only six to eight months.

Moulting occurs whenever the animal outgrows its rigid exoskeleton. Young animals, growing faster, moult more often than older and larger ones. The frequency of moulting varies widely from species to species and is, even within one species, subject to many external factors such as the latitude, the water temperature, and the availability of food. The subtropical species Nyctiphanes simplex, for instance, has an overall inter-moult period in the range of two to seven days: larvae moult on the average every four days, while juveniles and adults do so on average every six days. For E. superba in the Antarctic sea, inter-moult periods ranging between 9 and 28 days depending on the temperature between −1 C have been observed, and for Meganyctiphanes norvegica in the North Sea

the inter-moult periods range also from 9 and 28 days but at temperatures between 2.5 and 15 °C (36.5 and 59 F). E. superba is able to reduce its body size when there is not enough food available, moulting also when its exoskeleton becomes too large. Similar shrinkage has also been observed for E. pacifica, a species occurring in the Pacific Ocean from polar to temperate zones, as an adaptation to abnormally high water temperatures. Shrinkage has been postulated for other temperate-zone species of krill as well.

Krill has been harvested as a food source for humans (okiami) and domesticated animals since the 19th century, in Japan maybe even earlier. Large-scale fishing developed only in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and now occurs only in Antarctic waters and in the seas around Japan. Historically, the largest krill fishery

Krill has been harvested as a food source for humans (okiami) and domesticated animals since the 19th century, in Japan maybe even earlier. Large-scale fishing developed only in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and now occurs only in Antarctic waters and in the seas around Japan. Historically, the largest krill fishery

nations were Japan and the Soviet Union, or, after the latter's dissolution, Russia and Ukraine

. A peak in krill harvest had been reached in 1983 with more than 528,000 tonnes in the Southern Ocean

alone (of which the Soviet Union produced 93%). In 1993, two events led to a drastic decline in krill production: first, Russia abandoned its operations, and second, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) defined maximum catch quotas for a sustainable exploitation

of Antarctic krill. The annual catch in Antarctic waters seems to have stabilised around 100,000 tonnes of krill, which is roughly one fiftieth of the CCAMLR catch quota. The main limiting factor is probably the high cost associated with Antarctic operations, although there are some political and legal issues as well. The fishery around Japan appears to have saturated at some 70,000 tonnes.

Experimental small-scale harvesting is being carried out in other areas, for example, fishing for Euphausia pacifica off British Columbia

and harvesting Meganyctiphanes norvegica, Thysanoessa raschii and Thysanoessa inermis in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. These experimental operations produce only a few hundred tonnes of krill per year. Nicol & Foster consider it unlikely that any large-scale harvesting operations in these areas will be started due to opposition from local fishing industries and conservation groups.

Krill tastes salty and somewhat stronger than shrimp

. For mass-consumption and commercially prepared products they must be peeled, because their exoskeleton

contains fluoride

s, which are toxic in high concentrations. There is a small but growing market for krill oil

as a dietary supplement

ingredient. Two clinical trial

s have been published; tests included lipid lowering, arthritis pain and function, and C-reactive protein.

Order (biology)

In scientific classification used in biology, the order is# a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, family, genus, and species, with order fitting in between class and family...

Euphausiacea of shrimp

Shrimp

Shrimp are swimming, decapod crustaceans classified in the infraorder Caridea, found widely around the world in both fresh and salt water. Adult shrimp are filter feeding benthic animals living close to the bottom. They can live in schools and can swim rapidly backwards. Shrimp are an important...

-like marine crustacean

Crustacean

Crustaceans form a very large group of arthropods, usually treated as a subphylum, which includes such familiar animals as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill and barnacles. The 50,000 described species range in size from Stygotantulus stocki at , to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span...

s. Also known as euphausiids, these small invertebrate

Invertebrate

An invertebrate is an animal without a backbone. The group includes 97% of all animal species – all animals except those in the chordate subphylum Vertebrata .Invertebrates form a paraphyletic group...

s are found in all oceans of the world. The common name krill comes from the Norwegian

Norwegian language

Norwegian is a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Norway, where it is the official language. Together with Swedish and Danish, Norwegian forms a continuum of more or less mutually intelligible local and regional variants .These Scandinavian languages together with the Faroese language...

word , meaning "young fry of fish", which is also often attributed to other species of fish.

Krill are considered an important trophic level

Trophic level

The trophic level of an organism is the position it occupies in a food chain. The word trophic derives from the Greek τροφή referring to food or feeding. A food chain represents a succession of organisms that eat another organism and are, in turn, eaten themselves. The number of steps an organism...

connection – near the bottom of the food chain

Food chain

A food web depicts feeding connections in an ecological community. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one of two categories called trophic levels: 1) the autotrophs, and 2) the heterotrophs...

– because they feed on phytoplankton

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton are the autotrophic component of the plankton community. The name comes from the Greek words φυτόν , meaning "plant", and πλαγκτός , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter". Most phytoplankton are too small to be individually seen with the unaided eye...

and to a lesser extent zooplankton

Zooplankton

Zooplankton are heterotrophic plankton. Plankton are organisms drifting in oceans, seas, and bodies of fresh water. The word "zooplankton" is derived from the Greek zoon , meaning "animal", and , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter"...

, converting these into a form suitable for many larger animals for whom krill makes up the largest part of their diet. In the Southern Ocean

Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60°S latitude and encircling Antarctica. It is usually regarded as the fourth-largest of the five principal oceanic divisions...

, one species, the Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, is a species of krill found in the Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a shrimp-like crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000–30,000 individual animals per cubic metre...

, Euphausia superba, makes up an estimated biomass

Biomass (ecology)

Biomass, in ecology, is the mass of living biological organisms in a given area or ecosystem at a given time. Biomass can refer to species biomass, which is the mass of one or more species, or to community biomass, which is the mass of all species in the community. It can include microorganisms,...

of over 500000000 tonnes (492,101,766.6 LT), roughly twice that of humans. Of this, over half is eaten by whales, seals, penguins, squid and fish each year, and is replaced by growth and reproduction. Most krill species display large daily vertical migrations

Diel vertical migration

Diel vertical migration, also known as diurnal vertical migration, is a pattern of movement that some organisms living in the ocean and in lakes undertake each day. Usually organisms move up to the epipelagic zone at night and return to the mesopelagic zone of the oceans or to the hypolimnion zone...

, thus providing food for predators near the surface at night and in deeper waters during the day.

Commercial fishing of krill is done in the Southern Ocean

Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60°S latitude and encircling Antarctica. It is usually regarded as the fourth-largest of the five principal oceanic divisions...

and in the waters around Japan. The total global harvest amounts to 150000 – annually, most of this from the Scotia Sea

Scotia Sea

The Scotia Sea is partly in the Southern Ocean and mostly in the South Atlantic Ocean.-Location and description:Habitually stormy and cold, the Scotia Sea is the area of water between Tierra del Fuego, South Georgia, South Sandwich Islands, South Orkney Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula, and...

. Most of the krill catch is used for aquaculture

Aquaculture

Aquaculture, also known as aquafarming, is the farming of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, molluscs and aquatic plants. Aquaculture involves cultivating freshwater and saltwater populations under controlled conditions, and can be contrasted with commercial fishing, which is the...

and aquarium

Aquarium

An aquarium is a vivarium consisting of at least one transparent side in which water-dwelling plants or animals are kept. Fishkeepers use aquaria to keep fish, invertebrates, amphibians, marine mammals, turtles, and aquatic plants...

feeds, as bait

Bait (luring substance)

Bait is any substance used to attract prey, e.g. in a mousetrap.-In Australia:Baiting in Australia refers to specific campaigns to control foxes, wild dogs and dingos by poisoning in areas where they are a problem...

in sport fishing, or in the pharmaceutical industry. In Japan and Russia, krill is also used for human consumption and is known as in Japan.

Taxonomy

Krill belong to the large arthropodArthropod

An arthropod is an invertebrate animal having an exoskeleton , a segmented body, and jointed appendages. Arthropods are members of the phylum Arthropoda , and include the insects, arachnids, crustaceans, and others...

subphylum

Subphylum

In life, a subphylum is a taxonomic rank intermediate between phylum and superclass. The rank of subdivision in plants and fungi is equivalent to subphylum.Not all phyla are divided into subphyla...

, the Crustacea

Crustacean

Crustaceans form a very large group of arthropods, usually treated as a subphylum, which includes such familiar animals as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill and barnacles. The 50,000 described species range in size from Stygotantulus stocki at , to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span...

. The most familiar and largest group of crustaceans, the class

Class (biology)

In biological classification, class is* a taxonomic rank. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, order, family, genus, and species, with class fitting between phylum and order...

Malacostraca

Malacostraca

Malacostraca is the largest of the six classes of crustaceans, containing over 25,000 extant species, divided among 16 orders. Its members display a greater diversity of body forms than any other class of animals, and include crabs, lobsters, shrimp, krill, woodlice, scuds , mantis shrimp and many...

, includes the superorder

Order (biology)

In scientific classification used in biology, the order is# a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, family, genus, and species, with order fitting in between class and family...

Eucarida

Eucarida

Eucarida is a superorder of the Malacostraca, a class of the crustacean subphylum, comprising the decapods, krill and Amphionides. They are characterised by having the carapace fused to all thoracic segments, and by the possession of stalked eyes....

comprising the three orders, Euphausiacea or krill, Decapoda

Decapoda

The decapods or Decapoda are an order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, including many familiar groups, such as crayfish, crabs, lobsters, prawns and shrimp. Most decapods are scavengers. It is estimated that the order contains nearly 15,000 species in around 2,700 genera, with...

(shrimp, lobsters, crabs), and the minuscule Amphionides

Amphionides

Amphionides reynaudii is the sole representative of the order Amphionidacea, and is a small planktonic crustacean found throughout the world's tropical oceans, mostly in shallow waters.-Description:...

.

The order Euphasiacea comprises two families

Family (biology)

In biological classification, family is* a taxonomic rank. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, genus, and species, with family fitting between order and genus. As for the other well-known ranks, there is the option of an immediately lower rank, indicated by the...

. The more abundant Euphausiidae contains ten different genera

Genus

In biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

with a total of 85 species. Of these, the genus Euphausia

Euphausia

Euphausia is the largest genus of krill, and is placed in the family Euphausiidae. There are 31 species known in this genus, including Antarctic krill and ice krill from the Southern Ocean, and North Pacific krill in the Pacific Ocean.*Euphausia americana Hansen, 1911*Euphausia brevis Hansen,...

is the largest, with 31 species. The lesser known family, the Bentheuphausiidae, has only one species, Bentheuphausia amblyops

Bentheuphausia amblyops

Bentheuphausia amblyops, the deep sea krill is a species of krill, small shrimp-like crustaceans living in the ocean. B. amblyops is the only species within its genus, which in turn is the only genus within the family Bentheuphausiidae. All the 85 other species of krill known are classified in the...

, a bathypelagic krill living in deep waters below 1000 metres (3,280.8 ft). It is considered the most primitive living species of all krill.

Well-known species of the Euphausiidae of commercial krill fisheries

Krill fishery

The krill fishery is the commercial fishery of krill, small shrimp-like marine animals that live in the oceans world-wide. Estimates for how much krill there is vary wildly, depending on the methodology used. They range from 125–725 million tonnes of biomass globally...

include Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, is a species of krill found in the Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a shrimp-like crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000–30,000 individual animals per cubic metre...

(Euphausia superba), Pacific krill

Pacific krill

Euphausia pacifica, the North Pacific krill, is a euphausid that lives in the northern Pacific Ocean.In Japan, E. pacifica is called isada krill or . It is found from Suruga Bay northwards, including all of the Sea of Japan and the south-western part of the Sea of Okhotsk. E. pacifica is fished...

(Euphausia pacifica) and Northern krill

Northern krill

Northern krill, Meganyctiphanes norvegica, is a species of krill that lives in the North Atlantic Ocean. It is an important component of the zooplankton, providing food for whales, fish and birds. M...

(Meganyctiphanes norvegica).

Phylogeny

The order Euphausiacea is believed to be monophyleticMonophyly

In common cladistic usage, a monophyletic group is a taxon which forms a clade, meaning that it contains all the descendants of the possibly hypothetical closest common ancestor of the members of the group. The term is synonymous with the uncommon term holophyly...

due to several unique conserved morphological characteristics (autapomorphy

Autapomorphy

In cladistics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given terminal group. That is, it is found only in one member of a clade, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to the group...

) such as the naked filamentous gills or the thin thoracopods. and by molecular studies.

There have been many theories of the location of the order Euphausiacea, in fact since the first description of Thysanopode tricuspide by Henri Milne-Edwards

Henri Milne-Edwards

Henri Milne-Edwards was an eminent French zoologist.Henri Milne-Edwards was the 27th child of William Edwards, an English planter and militia colonel in Jamaica and Elisabeth Vaux, a French. He was born in Bruges, Belgium, where his parents had retired. At that time, Bruges was a part of the...

in 1830, the similarity of their biramous thoracopods had led zoologists to group euphausiids and Mysidacea in the order of Schizopoda

Schizopoda

Schizopoda is a former taxonomical classification of a division of the class Malacostraca. Although it was split in 1883 by Johan Erik Vesti Boas into the two distinct orders Mysidacea and Euphausiacea, the order Schizopoda continued to be in use until the 1930s....

, which was split by Johan Erik Vesti Boas

Johan Erik Vesti Boas

Johan Erik Vesti Boas , also J.E.V. Boas, was a Danish zoologist and a disciple of Carl Gegenbaur and Steenstrup. During the beginning and end of his career, Johan Erik Vesti Boas worked at the Zoological Museum of Copenhagen...

in 1883 into two separate orders. Later, William Thomas Calman

William Thomas Calman

William Thomas Calman was a Scottish zoologist, specialising in the Crustacea.He was born in Dundee, studying at the High School. In the scientific societies in the city, he met D'Arcy Thompson. He later became Thompson's lab boy, which allowed him to attend lectures at University College, Dundee...

(1904) ranked the Mysidacea

Mysidacea

Mysida is a group of small, shrimp-like crustaceans, an order in the malacostracan superorder Peracarida. Their common name opossum shrimps stems from the presence of a brood pouch, or marsupium, in females. Mysids are mostly found in marine waters throughout the world, but are also important in...

in the Peracarida super-order and euphausiids in Eucarida super-order, although even up to the 1930s the order Schizopoda was advocated. It was later also proposed that order Euphausiacea should be grouped with the Penaeidae

Penaeidae

Penaeidae is a family of prawns, although they are often referred to as penaeid shrimp. It contains many species of economic importance, such as the tiger prawn , whiteleg shrimp, Atlantic white shrimp and Indian prawn. Many prawns are the subject of commercial fishery, and farming, both in marine...

(family of prawns) in the Decapoda based on developmental similarities, as noted by Robert Gurney

Robert Gurney

Robert Gurney was a British zoologist most famous for his monographs on British Freshwater Copepoda and the Larvae of Decapod Crustacea . He was not affiliated with any institution, but worked at home, initially in Norfolk, and later near Oxford...

and Isabella Gordon

Isabella Gordon

Isabella Gordon, D.Sc., O.B.E. was an English biological scientist. Gordon specialised in carcinology, the study of crustaceans, and published many papers and monographs on the Crustacea. She worked at the British Museum as Assistant Keeper of Crustacea until her retirement in 1966. Gordon...

. The reason for this debate is that krill share some morphological features of decapods and others of mysids.

Molecular studies have also no been able to unambiguously group them, possibly due to the lack of many key rare species such as Bentheuphausia amblyops in krill and Amphionides reynaudii in Eucarida. One study supports Eucarida monophyly (with basal Mysida), another groups Euphausiacea with Mysida (the Schizopoda), while yet another groups Euphausiacea with Hoplocarida.

Timeline

Unusual for crustaceans, no fossil has been found that can be unequivocally assigned to the order Euphausiacea. Some extinct eumalacostracaEumalacostraca

The Eumalacostraca are a subclass of crustaceans, containing almost all living malacostracans, about 40,000 described species. The remaining subclasses are the Phyllocarida and possibly the Hoplocarida or mantis shrimps....

n taxa have been thought to be euphausiaceans such as Anthracophausia, Crangopsis

Crangopsis

Crangopsis is an extinct genus of crustacean....

– now assigned to the Aeschronectida

Aeschronectida

Aeschronectida is an extinct order of mantis shrimp-like crustaceans ....

(Hoplocarida) – and Palaeomysis. Consequently the dating of the speciation

Speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which new biological species arise. The biologist Orator F. Cook seems to have been the first to coin the term 'speciation' for the splitting of lineages or 'cladogenesis,' as opposed to 'anagenesis' or 'phyletic evolution' occurring within lineages...

events have been estimated by means of molecular clock

Molecular clock

The molecular clock is a technique in molecular evolution that uses fossil constraints and rates of molecular change to deduce the time in geologic history when two species or other taxa diverged. It is used to estimate the time of occurrence of events called speciation or radiation...

methods, which place the last common ancestor of the krill family Euphausiidae (order Euphausiacea minus Bentheuphausia amblyops) to have lived in the Lower Cretaceous

Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous or the Lower Cretaceous , is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous...

about .

Distribution

Bentheuphausia amblyops

Bentheuphausia amblyops, the deep sea krill is a species of krill, small shrimp-like crustaceans living in the ocean. B. amblyops is the only species within its genus, which in turn is the only genus within the family Bentheuphausiidae. All the 85 other species of krill known are classified in the...

, a bathypelagic

Bathyal zone

The bathyal zone or bathypelagic – from Greek βαθύς , deep – is that part of the pelagic zone that extends from a depth of 1000 to 4000 metres below the ocean surface. It lies between the mesopelagic above, and the abyssopelagic below. The average temperature hovers at about 39°F...

species, has a cosmopolitan distribution

Cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, a taxon is said to have a cosmopolitan distribution if its range extends across all or most of the world in appropriate habitats. For instance, the killer whale has a cosmopolitan distribution, extending over most of the world's oceans. Other examples include humans, the lichen...

within its deep-sea habitat.

Species of the genus Thysanoessa

Thysanoessa

Thysanoessa is a genus of krill , containing the following species:*Thysanoessa gregaria G. O. Sars, 1885*Thysanoessa inermis *Thysanoessa inspinata Nemoto, 1963...

occur in both the Atlantic

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

and Pacific

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

oceans. The Pacific is home to Euphausia pacifica. Northern krill

Northern krill

Northern krill, Meganyctiphanes norvegica, is a species of krill that lives in the North Atlantic Ocean. It is an important component of the zooplankton, providing food for whales, fish and birds. M...

occur across the Atlantic from the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

northward.

Species with neritic distributions include the four species of the genus Nyctiphanes

Nyctiphanes

Nyctiphanes is a genus of krill, containing the following species:*Nyctiphanes australis G. O. Sars, 1883*Nyctiphanes capensis Hansen, 1911*Nyctiphanes couchii *Nyctiphanes simplex Hansen, 1911...

. They are highly abundant along the upwelling

Upwelling

Upwelling is an oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water towards the ocean surface, replacing the warmer, usually nutrient-depleted surface water. The increased availability in upwelling regions results in high levels of primary...

regions of the California

California Current

The California Current is a Pacific Ocean current that moves south along the western coast of North America, beginning off southern British Columbia, and ending off southern Baja California. There are five major coastal currents affiliated with upwelling zones...

, Humboldt

Humboldt Current

The Humboldt Current , also known as the Peru Current, is a cold, low-salinity ocean current that flows north-westward along the west coast of South America from the southern tip of Chile to northern Peru. It is an eastern boundary current flowing in the direction of the equator, and can extend...

, Benguela

Benguela Current

The Benguela Current is the broad, northward flowing ocean current that forms the eastern portion of the South Atlantic Ocean gyre. The current extends from roughly Cape Point in the south, to the position of the Angola-Benguela Front in the north, at around 16°S. The current is driven by the...

, and Canarias

Canary Current

The Canary Current is a wind-driven surface current that is part of the North Atlantic Gyre. This eastern boundary current branches south from the North Atlantic Current and flows southwest about as far as Senegal where it turns west and later joins the Atlantic North Equatorial Current. The...

current system

Ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of ocean water generated by the forces acting upon this mean flow, such as breaking waves, wind, Coriolis effect, cabbeling, temperature and salinity differences and tides caused by the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun...

s. Another species having only neritic distribution is E. crystallorophias, which occurs only along the Antarctic coastline (and thus also is endemic to that region).

Species with endemic distributions include Nyctiphanes capensis, which occurs only in the Benguela current, E. mucronata in the Humboldt current, and the six Euphausia species native to the Southern Ocean.

In the Antarctic, seven species are known, one species of the genus Thysanoessa (T. macrura) and six of the genus Euphausia. The Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, is a species of krill found in the Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a shrimp-like crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000–30,000 individual animals per cubic metre...

(Euphausia superba) commonly lives at depths of as much as 100 m (328.1 ft), whereas ice krill (Euphausia crystallorophias

Euphausia crystallorophias

Euphausia crystallorophias is a species of krill, sometimes called ice krill, crystal krill, or Antarctic coastal krill. It lives in the coastal waters around Antarctica, further south than any other species of krill...

) have been recorded at a depth of 4000 m (13,123.4 ft), though they commonly live at depths of at most 300–600 m (984.3–1,968.5 ft). Both are found at latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

s south of 55° S

55th parallel south

The 55th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 55 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean and South America....

, with E. crystallorophias dominating south of 74° S

74th parallel south

The 74th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 74 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane in the Antarctic. The parallel passes through the Southern Ocean and Antarctica....

and in regions of pack ice. Other species known in the Southern Ocean

Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60°S latitude and encircling Antarctica. It is usually regarded as the fourth-largest of the five principal oceanic divisions...

are E. frigida, E. longirostris, E. triacantha and E. vallentini.

Anatomy and morphology

Crustacean

Crustaceans form a very large group of arthropods, usually treated as a subphylum, which includes such familiar animals as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, krill and barnacles. The 50,000 described species range in size from Stygotantulus stocki at , to the Japanese spider crab with a leg span...

s and have a chitin

Chitin

Chitin n is a long-chain polymer of a N-acetylglucosamine, a derivative of glucose, and is found in many places throughout the natural world...

ous exoskeleton

Exoskeleton

An exoskeleton is the external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to the internal skeleton of, for example, a human. In popular usage, some of the larger kinds of exoskeletons are known as "shells". Examples of exoskeleton animals include insects such as grasshoppers...

made up of three segments: the cephalon (head), the thorax, and the abdomen

Abdomen

In vertebrates such as mammals the abdomen constitutes the part of the body between the thorax and pelvis. The region enclosed by the abdomen is termed the abdominal cavity...

. The first two segments are fused into one segment, the cephalothorax

Cephalothorax

The cephalothorax is a tagma of various arthropods, comprising the head and the thorax fused together, as distinct from the abdomen behind. The word cephalothorax is derived from the Greek words for head and thorax...

. This outer shell of krill is transparent in most species. Krill feature intricate compound eyes; some species can adapt to different lighting conditions through the use of screening pigment

Pigment

A pigment is a material that changes the color of reflected or transmitted light as the result of wavelength-selective absorption. This physical process differs from fluorescence, phosphorescence, and other forms of luminescence, in which a material emits light.Many materials selectively absorb...

s. They have two antennae

Antenna (biology)

Antennae in biology have historically been paired appendages used for sensing in arthropods. More recently, the term has also been applied to cilium structures present in most cell types of eukaryotes....

and several pairs of thoracic legs called pereiopods or thoracopods, so named because they are attached to the thorax; their number varies among genera and species. These thoracic legs include the feeding legs and the grooming legs. Additionally all species have five swimming legs called pleopods or "swimmerets", very similar to those of a lobster or freshwater crayfish. Most krill are about 1–2 cm (0.393700787401575–0.78740157480315 in) long as adults; a few species grow to sizes on the order of 6–15 cm (2.4–5.9 in). The largest krill species is the bathypelagic Thysanopoda spinicauda. Krill can be easily distinguished from other crustaceans such as true shrimp

Shrimp

Shrimp are swimming, decapod crustaceans classified in the infraorder Caridea, found widely around the world in both fresh and salt water. Adult shrimp are filter feeding benthic animals living close to the bottom. They can live in schools and can swim rapidly backwards. Shrimp are an important...

by their externally visible gill

Gill

A gill is a respiratory organ found in many aquatic organisms that extracts dissolved oxygen from water, afterward excreting carbon dioxide. The gills of some species such as hermit crabs have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are kept moist...

s.

Appendage

In invertebrate biology, an appendage is an external body part, or natural prolongation, that protrudes from an organism's body . It is a general term that covers any of the homologous body parts that may extend from a body segment...

s, the thoracopods, form very fine combs with which they can filter out their food from the water. These filters can be very fine indeed in those species (such as Euphausia spp.) that feed primarily on phytoplankton

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton are the autotrophic component of the plankton community. The name comes from the Greek words φυτόν , meaning "plant", and πλαγκτός , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter". Most phytoplankton are too small to be individually seen with the unaided eye...

, in particular on diatom

Diatom

Diatoms are a major group of algae, and are one of the most common types of phytoplankton. Most diatoms are unicellular, although they can exist as colonies in the shape of filaments or ribbons , fans , zigzags , or stellate colonies . Diatoms are producers within the food chain...

s, which are unicellular algae

Algae

Algae are a large and diverse group of simple, typically autotrophic organisms, ranging from unicellular to multicellular forms, such as the giant kelps that grow to 65 meters in length. They are photosynthetic like plants, and "simple" because their tissues are not organized into the many...

. However, it is believed that krill are mostly omnivorous. A few species are carnivorous, preying on small zooplankton and fish larvae.

Except for Bentheuphausia amblyops, krill are bioluminescent

Bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by a living organism. Its name is a hybrid word, originating from the Greek bios for "living" and the Latin lumen "light". Bioluminescence is a naturally occurring form of chemiluminescence where energy is released by a chemical reaction in...

animals having organs called photophore

Photophore

A photophore is a light-emitting organ which appears as luminous spots on various marine animals, including fish and cephalopods. The organ can be simple, or as complex as the human eye; equipped with lenses, shutters, color filters and reflectors...

s that can emit light. The light is generated by an enzyme-catalysed chemiluminescence reaction, wherein a luciferin

Luciferin

Luciferins are a class of light-emitting biological pigments found in organisms that cause bioluminescence...

(a kind of pigment

Pigment

A pigment is a material that changes the color of reflected or transmitted light as the result of wavelength-selective absorption. This physical process differs from fluorescence, phosphorescence, and other forms of luminescence, in which a material emits light.Many materials selectively absorb...

) is activated by a luciferase

Luciferase

Luciferase is a generic term for the class of oxidative enzymes used in bioluminescence and is distinct from a photoprotein. One famous example is the firefly luciferase from the firefly Photinus pyralis. "Firefly luciferase" as a laboratory reagent usually refers to P...

enzyme

Enzyme

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates...

. Studies indicate that the luciferin of many krill species is a fluorescent

Fluorescence

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation of a different wavelength. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore lower energy, than the absorbed radiation...

tetrapyrrole

Polypyrrole

Polypyrrole is a chemical compound formed from a number of connected pyrrole ring structures. For example a tetrapyrrole is a compound with four pyrrole rings connected. Methine-bridged cyclic tetrapyrroles are called porphyrins. Polypyrroles are conducting polymers of the rigid-rod polymer host...

similar but not identical to dinoflagellate

Dinoflagellate

The dinoflagellates are a large group of flagellate protists. Most are marine plankton, but they are common in fresh water habitats as well. Their populations are distributed depending on temperature, salinity, or depth...

luciferin and that the krill probably do not produce this substance themselves but acquire it as part of their diet, which contains dinoflagellates. Krill photophores are complex organs with lenses and focusing abilities, and they can be rotated by muscles. The precise function of these organs is as yet unknown; they might have a purpose in mating, social interaction or orientation. Some researchers (e.g., Lindsay & Latz and Johnsen) have proposed that krill use the light as a form of counter-illumination camouflage to compensate their shadow against the ambient light from above to make themselves less visible to predators from below.

Behaviour

Most krill are swarmSwarm

Swarm behaviour, or swarming, is a collective behaviour exhibited by animals of similar size which aggregate together, perhaps milling about the same spot or perhaps moving en masse or migrating in some direction. As a term, swarming is applied particularly to insects, but can also be applied to...

ing animals; the sizes and densities of such swarms vary greatly depending on the species and the region. For Euphausia superba, there have been reports of swarms of up to 10,000 to 60,000 individuals per cubic metre. Swarming is a defensive mechanism, confusing smaller predators that would like to pick out single individuals. Krill typically follow a diurnal vertical migration

Diel vertical migration

Diel vertical migration, also known as diurnal vertical migration, is a pattern of movement that some organisms living in the ocean and in lakes undertake each day. Usually organisms move up to the epipelagic zone at night and return to the mesopelagic zone of the oceans or to the hypolimnion zone...

. Until recently it has been assumed that they spend the day at greater depths and rise during the night toward the surface. It has been found that the deeper they go, the more they reduce their activity, apparently to reduce encounters with predators and to conserve energy. Later work suggested that swimming activity in krill varied with stomach fullness. Satiated animals that had been feeding at the surface swim less actively and therefor sink below the mixed layer. As they sink they produce faeces which may mean that they have an important role to play in the Antarctic carbon cycle. Krill with empty stomachs were found to swim more actively and thus head towards the surface. This implies that vertical migration may be a bi or tri daily occurrence. Some species (e.g., Euphausia superba, E. pacifica, E. hanseni, Pseudeuphausia latifrons, and Thysanoessa spinifera) also form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

Feeding frenzy

In ecology, a feeding frenzy is a situation where oversaturation of a supply of food leads to rapid feeding by predatory animals. For example, a large school of fish can cause nearby sharks to enter a feeding frenzy. This can cause the sharks to go wild, biting anything that moves, including each...

among fish, birds and mammal predators, especially near the surface. When disturbed, a swarm scatters, and some individuals have even been observed to moult

Ecdysis

Ecdysis is the moulting of the cuticula in many invertebrates. This process of moulting is the defining feature of the clade Ecdysozoa, comprising the arthropods, nematodes, velvet worms, horsehair worms, rotifers, tardigrades and Cephalorhyncha...

instantaneously, leaving the exuvia

Exuvia

Exuviae is a term used in biology to describe the remains of an exoskeleton and related structures that are left after ecdysozoans have moulted...

behind as a decoy.

Krill normally swim at pace of 5–10 cm/s (2–3 body lengths per second), using their swimmerets for propulsion. Their larger migrations are subject to the currents in the ocean. When in danger, they show an escape reaction called lobstering

Caridoid escape reaction

The Caridoid Escape Reaction, also known as lobstering or tail-flipping, refers to an innate escape mechanism in marine and freshwater crustaceans such as lobsters, krill, shrimp and crayfish....

– flicking their caudal structures, the telson

Telson

The telson is the last division of the body of a crustacean. It is not considered a true segment because it does not arise in the embryo from teloblast areas as do real segments. It never carries any appendages, but a forked "tail" called the caudal furca is often present. Together with the...

and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second, which for large krill such as E. superba means around 0.8 m/s (3 ft/s). Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as micro-nektonic

Nekton

Nekton refers to the aggregate of actively swimming aquatic organisms in a body of water able to move independently of water currents....

life-forms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents. Larval forms of krill are generally considered zooplankton

Zooplankton

Zooplankton are heterotrophic plankton. Plankton are organisms drifting in oceans, seas, and bodies of fresh water. The word "zooplankton" is derived from the Greek zoon , meaning "animal", and , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter"...

.

Ecology and life history

Food chain

A food web depicts feeding connections in an ecological community. Ecologists can broadly lump all life forms into one of two categories called trophic levels: 1) the autotrophs, and 2) the heterotrophs...

. Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill

Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, is a species of krill found in the Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is a shrimp-like crustacean that lives in large schools, called swarms, sometimes reaching densities of 10,000–30,000 individual animals per cubic metre...

feed directly on phytoplankton

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton are the autotrophic component of the plankton community. The name comes from the Greek words φυτόν , meaning "plant", and πλαγκτός , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter". Most phytoplankton are too small to be individually seen with the unaided eye...

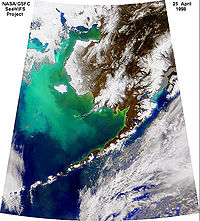

, converting the primary production

Primary production

400px|thumb|Global oceanic and terrestrial photoautotroph abundance, from September [[1997]] to August 2000. As an estimate of autotroph biomass, it is only a rough indicator of primary production potential, and not an actual estimate of it...

energy into a form suitable for consumption by larger animals that cannot feed directly on the minuscule algae. Some species like the Northern krill have a relatively small filtering basket and actively hunt for copepod

Copepod

Copepods are a group of small crustaceans found in the sea and nearly every freshwater habitat. Some species are planktonic , some are benthic , and some continental species may live in limno-terrestrial habitats and other wet terrestrial places, such as swamps, under leaf fall in wet forests,...

s and larger zooplankton

Zooplankton

Zooplankton are heterotrophic plankton. Plankton are organisms drifting in oceans, seas, and bodies of fresh water. The word "zooplankton" is derived from the Greek zoon , meaning "animal", and , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter"...

. Many animals feed on krill, ranging from smaller animals like fish

Fish

Fish are a paraphyletic group of organisms that consist of all gill-bearing aquatic vertebrate animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish, as well as various extinct related groups...

or penguin

Penguin

Penguins are a group of aquatic, flightless birds living almost exclusively in the southern hemisphere, especially in Antarctica. Highly adapted for life in the water, penguins have countershaded dark and white plumage, and their wings have become flippers...

s to larger ones like seals

Pinniped

Pinnipeds or fin-footed mammals are a widely distributed and diverse group of semiaquatic marine mammals comprising the families Odobenidae , Otariidae , and Phocidae .-Overview: Pinnipeds are typically sleek-bodied and barrel-shaped...

and even baleen whale

Baleen whale

The Baleen whales, also called whalebone whales or great whales, form the Mysticeti, one of two suborders of the Cetacea . Baleen whales are characterized by having baleen plates for filtering food from water, rather than having teeth. This distinguishes them from the other suborder of cetaceans,...

s.

Disturbances of an ecosystem

Ecosystem

An ecosystem is a biological environment consisting of all the organisms living in a particular area, as well as all the nonliving , physical components of the environment with which the organisms interact, such as air, soil, water and sunlight....

resulting in a decline in the krill population can have far-reaching effects. During a coccolithophore

Coccolithophore

Coccolithophores are single-celled algae, protists, and phytoplankton belonging to the division of haptophytes. They are distinguished by special calcium carbonate plates of uncertain function called coccoliths , which are important microfossils...

bloom in the Bering Sea

Bering Sea

The Bering Sea is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean. It comprises a deep water basin, which then rises through a narrow slope into the shallower water above the continental shelves....

in 1998, for instance, the diatom

Diatom

Diatoms are a major group of algae, and are one of the most common types of phytoplankton. Most diatoms are unicellular, although they can exist as colonies in the shape of filaments or ribbons , fans , zigzags , or stellate colonies . Diatoms are producers within the food chain...

concentration dropped in the affected area. Krill cannot feed on the smaller coccolithophores, and consequently the krill population (mainly E. pacifica) in that region declined sharply. This in turn affected other species: the shearwater

Shearwater

Shearwaters are medium-sized long-winged seabirds. There are more than 30 species of shearwaters, a few larger ones in the genus Calonectris and many smaller species in the genus Puffinus...

population dropped, and the incident was even thought to have been a reason for salmon

Salmon

Salmon is the common name for several species of fish in the family Salmonidae. Several other fish in the same family are called trout; the difference is often said to be that salmon migrate and trout are resident, but this distinction does not strictly hold true...

not returning to the rivers of western Alaska

Alaska

Alaska is the largest state in the United States by area. It is situated in the northwest extremity of the North American continent, with Canada to the east, the Arctic Ocean to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the west and south, with Russia further west across the Bering Strait...

that season.

Other factors besides predation and food availability can influence the mortality rate in krill populations. As temperatures have risen over the past couple decades, Antarctic sea ice

Sea ice

Sea ice is largely formed from seawater that freezes. Because the oceans consist of saltwater, this occurs below the freezing point of pure water, at about -1.8 °C ....

has melted. In this way, climate change poses a threat to krill populations as they feed on algae beneath the ice. There are several single-celled endoparasitoidic ciliate

Ciliate

The ciliates are a group of protozoans characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to flagella but typically shorter and present in much larger numbers with a different undulating pattern than flagella...

s of the genus Collinia that can infect different species of krill and cause massive decline in affected populations. Such diseases have been reported for Thysanoessa inermis in the Bering Sea and also for E. pacifica, Thysanoessa spinifera, and T. gregaria off the North American Pacific coast. There are also some ectoparasites of the family Dajidae

Dajidae

Dajidae is a family of marine isopod crustaceans in the suborder Cymothoida. The original description was made by Giard and Bonnier in 1887.Members of this family are ectoparasites of krill...

(epicaridean isopods) that afflict krill (and also shrimp

Shrimp

Shrimp are swimming, decapod crustaceans classified in the infraorder Caridea, found widely around the world in both fresh and salt water. Adult shrimp are filter feeding benthic animals living close to the bottom. They can live in schools and can swim rapidly backwards. Shrimp are an important...

and mysids); one such parasite is Oculophryxus bicaulis, which has been found on the krill Stylocheiron affine and S. longicorne. It attaches itself to the eyestalk of the animal and sucks blood from its head; it is believed that it inhibits the reproduction of its host, as none of the afflicted animals found reached maturity.

Life history

Metanauplius

Metanauplius is an early larval stage of some crustaceans such as krill. It follows the nauplius stage.In sac-spawning krill, there is an intermediary phase called pseudometanauplius, a newly hatched form distinguished from older metanauplii by its extremely short abdomen...

, calyptopsis, and furcilia stages, each of which is sub-divided into several sub-stages. The pseudometanauplius stage is exclusive to species that lay their eggs within an ovigerous sac: so-called "sac-spawners". The larvae grow and moult

Ecdysis

Ecdysis is the moulting of the cuticula in many invertebrates. This process of moulting is the defining feature of the clade Ecdysozoa, comprising the arthropods, nematodes, velvet worms, horsehair worms, rotifers, tardigrades and Cephalorhyncha...

multiple times as they develop, shedding their rigid exoskeleton whenever it becomes too small and growing a new one. Smaller animals moult more frequently than larger ones. Up through the metanauplius stage, the larvae are nourished by yolk reserves within their body. Only by the calyptopsis stages has differentiation

Cellular differentiation

In developmental biology, cellular differentiation is the process by which a less specialized cell becomes a more specialized cell type. Differentiation occurs numerous times during the development of a multicellular organism as the organism changes from a simple zygote to a complex system of...

progressed far enough for them to develop a mouth and a digestive tract, and they begin to feed upon phytoplankton

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton are the autotrophic component of the plankton community. The name comes from the Greek words φυτόν , meaning "plant", and πλαγκτός , meaning "wanderer" or "drifter". Most phytoplankton are too small to be individually seen with the unaided eye...

. By that time, the larvae must have reached the photic zone

Photic zone

The photic zone or euphotic zone is the depth of the water in a lake or ocean that is exposed to sufficient sunlight for photosynthesis to occur...

, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish, for their yolk reserves are exhausted by then and they would starve otherwise. During the furcilia stages, segments with pairs of swimmerets are added, beginning at the frontmost segments. Each new pair becomes functional only at the next moult. The number of segments added during any one of the furcilia stages may vary even within one species depending on environmental conditions. After the final furcilia stage, the krill emerges in a shape similar to an adult, but it is still an immature juvenile, that only subsequently develops gonad

Gonad

The gonad is the organ that makes gametes. The gonads in males are the testes and the gonads in females are the ovaries. The product, gametes, are haploid germ cells. For example, spermatozoon and egg cells are gametes...

s and matures.

During the mating season, which varies depending on the species and the climate, the male deposits a sperm sack

Spermatophore

A spermatophore or sperm ampulla is a capsule or mass created by males of various animal species, containing spermatozoa and transferred in entirety to the female's ovipore during copulation...

at the genital opening (named thelycum) of the female. The females can carry several thousand eggs in their ovary

Ovary

The ovary is an ovum-producing reproductive organ, often found in pairs as part of the vertebrate female reproductive system. Ovaries in anatomically female individuals are analogous to testes in anatomically male individuals, in that they are both gonads and endocrine glands.-Human anatomy:Ovaries...

, which may then account for as much as one third of the animal's body mass. Krill can have multiple broods in one season, with interbrood periods in the order of days.

Some high-latitude species of krill can live for more than six years (e.g., Euphausia superba); others, such as the mid-latitude species Euphausia pacifica, live for only two years. Subtropical or tropical

Tropics

The tropics is a region of the Earth surrounding the Equator. It is limited in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the northern hemisphere at approximately N and the Tropic of Capricorn in the southern hemisphere at S; these latitudes correspond to the axial tilt of the Earth...

species' longevity is still shorter, e.g., Nyctiphanes simplex, which usually lives for only six to eight months.

Moulting occurs whenever the animal outgrows its rigid exoskeleton. Young animals, growing faster, moult more often than older and larger ones. The frequency of moulting varies widely from species to species and is, even within one species, subject to many external factors such as the latitude, the water temperature, and the availability of food. The subtropical species Nyctiphanes simplex, for instance, has an overall inter-moult period in the range of two to seven days: larvae moult on the average every four days, while juveniles and adults do so on average every six days. For E. superba in the Antarctic sea, inter-moult periods ranging between 9 and 28 days depending on the temperature between −1 C have been observed, and for Meganyctiphanes norvegica in the North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

the inter-moult periods range also from 9 and 28 days but at temperatures between 2.5 and 15 °C (36.5 and 59 F). E. superba is able to reduce its body size when there is not enough food available, moulting also when its exoskeleton becomes too large. Similar shrinkage has also been observed for E. pacifica, a species occurring in the Pacific Ocean from polar to temperate zones, as an adaptation to abnormally high water temperatures. Shrinkage has been postulated for other temperate-zone species of krill as well.

Economy

Krill fishery

The krill fishery is the commercial fishery of krill, small shrimp-like marine animals that live in the oceans world-wide. Estimates for how much krill there is vary wildly, depending on the methodology used. They range from 125–725 million tonnes of biomass globally...

nations were Japan and the Soviet Union, or, after the latter's dissolution, Russia and Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

. A peak in krill harvest had been reached in 1983 with more than 528,000 tonnes in the Southern Ocean

Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60°S latitude and encircling Antarctica. It is usually regarded as the fourth-largest of the five principal oceanic divisions...

alone (of which the Soviet Union produced 93%). In 1993, two events led to a drastic decline in krill production: first, Russia abandoned its operations, and second, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) defined maximum catch quotas for a sustainable exploitation

Sustainable fisheries

Sustainability in fisheries combines theoretical disciplines, such as the population dynamics of fisheries, with practical strategies, such as avoiding overfishing through techniques such as individual fishing quotas, curtailing destructive and illegal fishing practices by lobbying for appropriate...

of Antarctic krill. The annual catch in Antarctic waters seems to have stabilised around 100,000 tonnes of krill, which is roughly one fiftieth of the CCAMLR catch quota. The main limiting factor is probably the high cost associated with Antarctic operations, although there are some political and legal issues as well. The fishery around Japan appears to have saturated at some 70,000 tonnes.

Experimental small-scale harvesting is being carried out in other areas, for example, fishing for Euphausia pacifica off British Columbia

British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost of Canada's provinces and is known for its natural beauty, as reflected in its Latin motto, Splendor sine occasu . Its name was chosen by Queen Victoria in 1858...

and harvesting Meganyctiphanes norvegica, Thysanoessa raschii and Thysanoessa inermis in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. These experimental operations produce only a few hundred tonnes of krill per year. Nicol & Foster consider it unlikely that any large-scale harvesting operations in these areas will be started due to opposition from local fishing industries and conservation groups.

Krill tastes salty and somewhat stronger than shrimp

Shrimp