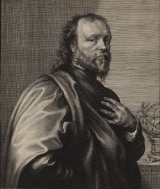

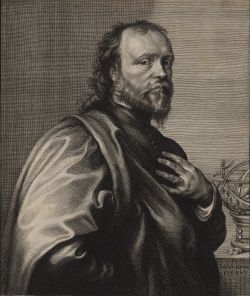

Kenelm Digby

Encyclopedia

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

courtier

Courtier

A courtier is a person who is often in attendance at the court of a king or other royal personage. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the residence of the monarch, and social and political life were often completely mixed together...

and diplomat

Diplomat

A diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

. He was also a highly reputed natural philosopher, and known as a leading Roman Catholic intellectual and Blackloist. For his versatility, Anthony à Wood

Anthony Wood

Anthony Wood or Anthony à Wood was an English antiquary.-Early life:Anthony Wood was the fourth son of Thomas Wood , BCL of Oxford, where Anthony was born...

called him the "magazine of all arts".

Early life and career

He was born at GayhurstGayhurst

Gayhurst is a village and civil parish in the Borough of Milton Keynes, ceremonial Buckinghamshire in England. It is about two and a half miles NNW of Newport Pagnell....

, Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan home county in South East England. The county town is Aylesbury, the largest town in the ceremonial county is Milton Keynes and largest town in the non-metropolitan county is High Wycombe....

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. He was of gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

stock, but his family's adherence to Roman Catholicism coloured his career. His father, Sir Everard

Everard Digby

Sir Everard Digby was a member of the group of provincial English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Although he was raised in a Protestant household, and married a Protestant, Digby and his wife were converted to Catholicism by the Jesuit priest John Gerard...

, was executed in 1606 for his part in the Gunpowder Plot

Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I of England and VI of Scotland by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby.The plan was to blow up the House of...

. Kenelm was sufficiently in favour with James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

to be proposed as a member of Edmund Bolton

Edmund Bolton

Edmund Mary Bolton , English historian and poet, was born in 1575.-Life:Nothing is known of his family or origins, although he referred to himself as a distant relative of George Villiers. Brought up a Roman Catholic, he was educated at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. Bolton then lived in London at the...

's projected Royal Academy (with George Chapman

George Chapman

George Chapman was an English dramatist, translator, and poet. He was a classical scholar, and his work shows the influence of Stoicism. Chapman has been identified as the Rival Poet of Shakespeare's Sonnets by William Minto, and as an anticipator of the Metaphysical Poets...

, Michael Drayton

Michael Drayton

Michael Drayton was an English poet who came to prominence in the Elizabethan era.-Early life:He was born at Hartshill, near Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. Almost nothing is known about his early life, beyond the fact that in 1580 he was in the service of Thomas Goodere of Collingham,...

, Ben Jonson

Ben Jonson

Benjamin Jonson was an English Renaissance dramatist, poet and actor. A contemporary of William Shakespeare, he is best known for his satirical plays, particularly Volpone, The Alchemist, and Bartholomew Fair, which are considered his best, and his lyric poems...

, John Selden

John Selden

John Selden was an English jurist and a scholar of England's ancient laws and constitution and scholar of Jewish law...

, and Sir Henry Wotton).

He went to Gloucester Hall, Oxford in 1618, where he was taught by Thomas Allen

Thomas Allen (mathematician)

Thomas Allen was an English mathematician and astrologer.-Life:He was admitted scholar of Trinity College, Oxford, in 1561; and graduated as M.A. in 1567...

, but left without taking a degree. In time Allen bequeathed to Digby his library, and the latter donated it to the Bodleian.

He spent three years in Europe between 1620 and 1623, where Marie de Medici fell madly in love with him (as he later recounted). He was granted a Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

M.A. on the King's visit to the university in 1624. Around 1625, he married Venetia Stanley

Venetia Stanley

Venetia Anastasia Stanley Digby was a celebrated beauty of the Stuart period , renowned for her racy good looks and mysterious death...

, whose wooing he cryptically described in his memoirs. He had also become a member of the Privy Council

Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, usually known simply as the Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the Sovereign in the United Kingdom...

of Charles I of England

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

. Due to his Roman Catholicism being a hindrance in the way of government office, he switched to Anglicanism

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

.

In 1628, Digby became a privateer. On his flagship the Eagle later re-christened the Arabella

Arbella

The Arbella or Arabella was the flagship of the Winthrop Fleet on which, between April 8 and June 12, 1630, Governor John Winthrop, other members of the Company and Puritan emigrants transported themselves and the Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company from England to Salem, thereby giving legal...

: he arrived off Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

January 18 and captured several Spanish and Flemish vessels. From February 5 to March 27 he remained at anchor off Algiers

Algiers

' is the capital and largest city of Algeria. According to the 1998 census, the population of the city proper was 1,519,570 and that of the urban agglomeration was 2,135,630. In 2009, the population was about 3,500,000...

on account of the sickness of his men, and extracted a promise from the authorities of better treatment of the English ships. He seized a rich Dutch vessel near Majorca, and after other adventures gained a complete victory over the French and Venetian ships in the harbour of Iskanderun on the June 11. His successes, however, brought upon the English merchants the risk of reprisals, and he was urged to depart.

He returned to become a naval administrator and later Governor of Trinity House

Trinity House

The Corporation of Trinity House of Deptford Strond is the official General Lighthouse Authority for England, Wales and other British territorial waters...

. His wife died suddenly in 1633, prompting a famous deathbed portrait by Van Dyck and a eulogy by Ben Jonson

Ben Jonson

Benjamin Jonson was an English Renaissance dramatist, poet and actor. A contemporary of William Shakespeare, he is best known for his satirical plays, particularly Volpone, The Alchemist, and Bartholomew Fair, which are considered his best, and his lyric poems...

. (Digby was later Jonson's literary executor

Literary executor

A literary executor is a person with decision-making power in respect of a literary estate. According to Wills, Administration and Taxation: a practical guide "A will may appoint different executors to deal with different parts of the estate...

. Jonson's poem about Venetia is now mostly lost, because of the loss of the center sheet of a leaf of papers which held the only copy.) Digby, stricken with grief and the object of enough suspicion for the Crown to order an autopsy (rare at the time) on Venetia's body, secluded himself in Gresham College

Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in central London, England. It was founded in 1597 under the will of Sir Thomas Gresham and today it hosts over 140 free public lectures every year within the City of London.-History:Sir Thomas Gresham,...

and attempted to forget his personal woes through scientific experimentation and a return to Catholicism. At that period, public servants were often rewarded with patents of monopoly; Digby received the regional monopoly of sealing wax

Sealing wax

Sealing wax is a wax material of a seal which, after melting, quickly hardens forming a bond that is difficult to separate without noticeable tampering. Wax is used to verify something such as a document is unopened, to verify the sender's identity, for example with a signet ring, and as decoration...

in Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

and the Welsh Borders. This was a guaranteed income; more speculative were the monopolies of trade with the Gulf of Guinea

Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean between Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian is in the gulf....

and with Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

. These were doubtless more difficult to police.

Catholicism and Civil War

Digby became a Catholic once more in 1635. He went into voluntary exile in Paris, where he spent most of his time until 1660. There he met both Marin MersenneMarin Mersenne

Marin Mersenne, Marin Mersennus or le Père Mersenne was a French theologian, philosopher, mathematician and music theorist, often referred to as the "father of acoustics"...

and Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

.

Returning to support Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

in his struggle to establish episcopacy in Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

(the Bishops' Wars

Bishops' Wars

The Bishops' Wars , were conflicts, both political and military, which occurred in 1639 and 1640 centred around the nature of the governance of the Church of Scotland, and the rights and powers of the Crown...

), he found himself increasingly unpopular with the growing Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

party. He left England for France again in 1641. Following an incident in which he killed a French nobleman, Mont le Ros, in a duel, he returned to England via Flanders

Flanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

in 1642, and was jailed by the House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

. He was eventually released at the intervention of Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria was Queen consort of France and Navarre, regent for her son, Louis XIV of France, and a Spanish Infanta by birth...

, and went back again to France. He remained there during the remainder of the period of the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

. Parliament

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

declared his property in England forfeit.

Queen Henrietta Maria had fled England in 1644, and he became her Chancellor. He was then engaged in unsuccessful attempts to solicit support for the English monarchy from Pope Innocent X

Pope Innocent X

Pope Innocent X , born Giovanni Battista Pamphilj , was Pope from 1644 to 1655. Born in Rome of a family from Gubbio in Umbria who had come to Rome during the pontificate of Pope Innocent IX, he graduated from the Collegio Romano and followed a conventional cursus honorum, following his uncle...

. Following the establishment of The Protectorate

The Protectorate

In British history, the Protectorate was the period 1653–1659 during which the Commonwealth of England was governed by a Lord Protector.-Background:...

under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

, who believed in freedom of conscience, Digby was received by the government as a sort of unofficial representative of English Roman Catholics, and was sent in 1655 on a mission to the Papacy to try to reach an understanding. This again proved unsuccessful.

At the Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

, Digby found himself in favor with the new regime due to his ties with Henrietta Maria, the Queen Mother. However, he was often in trouble with Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

, and was once even banished from Court. Nonetheless, he was generally highly regarded until his death at the age of 62 from "the stone", likely caused by kidney stones.

Character and works

Digby published a work of apologeticsApologetics

Apologetics is the discipline of defending a position through the systematic use of reason. Early Christian writers Apologetics (from Greek ἀπολογία, "speaking in defense") is the discipline of defending a position (often religious) through the systematic use of reason. Early Christian writers...

in 1638, A Conference with a Lady about choice of a Religion. In it he argued that the Catholic Church, possessing alone the qualifications of universality, unity of doctrine and uninterrupted apostolic succession

Apostolic Succession

Apostolic succession is a doctrine, held by some Christian denominations, which asserts that the chosen successors of the Twelve Apostles, from the first century to the present day, have inherited the spiritual, ecclesiastical and sacramental authority, power, and responsibility that were...

, is the only true church, and that the intrusion of error into it is impossible.

Digby was regarded as an eccentric by contemporaries, partly because of his effusive personality, and partly because of his interests in scientific matters. Henry Stubbe called him "the very Pliny of our age for lying". He lived in a time when scientific enquiry had not settled down in any disciplined way. He spent enormous time and effort in the pursuits of astrology

Astrology

Astrology consists of a number of belief systems which hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world...

, and alchemy

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

which he studied in the 1630s with Van Dyck.

Notable among his pursuits was the concept of the Powder of Sympathy

Powder of Sympathy

Powder of sympathy was a form of sympathetic magic, current in 17th century in Europe, whereby a remedy was applied to the weapon that had caused a wound in the hope of healing the injury it had made. The method was first proposed by Rudolf Goclenius, Jr. and was later expanded upon by Sir Kenelm...

. This was a kind of sympathetic magic

Sympathetic magic

Sympathetic magic, also known as imitative magic, is a type of magic based on imitation or correspondence.-Similarity and contagion:The theory of sympathetic magic was first developed by Sir James George Frazer in The Golden Bough...

; one manufactured a powder using appropriate astrological

Astrology

Astrology consists of a number of belief systems which hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world...

techniques, and daubed it, not on the injured part, but on whatever had caused the injury. His book on this salve went through 29 editions. Synchronising the effects of the powder, which apparently caused a noticeable effect on the patient when applied, was actually suggested in 1687 as a means of solving the longitude

Longitude

Longitude is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east-west position of a point on the Earth's surface. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees, minutes and seconds, and denoted by the Greek letter lambda ....

problem.

In 1644 he published together two major philosophical treatises, The Nature of Bodies and On the Immortality of Reasonable Souls. The latter was translated into Latin in 1661 by John Leyburn

John Leyburn

John Leyburn was an English Roman Catholic priest, who became Vicar Apostolic of the London District, and thus the senior Roman Catholic prelate in England, from 1685 to 1702. He was not only a theologian, but also a mathematician, and an intimate friend of Descartes and Hobbes.-Life:He was the...

. These Two Treatises were his major natural-philosophical works, and showed a combination of Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism is a tradition of philosophy that takes its defining inspiration from the work of Aristotle. The works of Aristotle were initially defended by the members of the Peripatetic school, and, later on, by the Neoplatonists, who produced many commentaries on Aristotle's writings...

and atomism

Atomism

Atomism is a natural philosophy that developed in several ancient traditions. The atomists theorized that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void.According to Aristotle, atoms are indestructible and immutable and there are an infinite variety of shapes...

.

He was in touch with the leading intellectuals of the time, and was highly regarded by them; he was a founding member of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

and a member of its governing council from 1662 to 1663. His correspondence with Fermat

Pierre de Fermat

Pierre de Fermat was a French lawyer at the Parlement of Toulouse, France, and an amateur mathematician who is given credit for early developments that led to infinitesimal calculus, including his adequality...

contains the only extant mathematical proof by Fermat, a demonstration, using his method of descent, that the area of a Pythagorean triangle cannot be a square. His Discourse Concerning the Vegetation of Plants (1661) proved controversial among the Royal Society's members. He is credited with being the first person to note the importance of "vital air," or oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

, to the sustenance of plants.

Digby is known for the publication of a cookbook

Cookbook

A cookbook is a kitchen reference that typically contains a collection of recipes. Modern versions may also include colorful illustrations and advice on purchasing quality ingredients or making substitutions...

, The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Knight Opened

The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Knight Opened

The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie Kt. Opened, first printed in 1669, is a 17th century English cookbook and an excellent resource of the types of food that were eaten by persons of means in the early 17th century...

, but it was actually published by a close servant, from his notes, in 1669, several years after his death. It is currently considered an excellent source of period recipes, particularly for beverages such as mead

Mead

Mead , also called honey wine, is an alcoholic beverage that is produced by fermenting a solution of honey and water. It may also be produced by fermenting a solution of water and honey with grain mash, which is strained immediately after fermentation...

.

Digby is also considered the father of the modern wine bottle

Wine bottle

A wine bottle is a bottle used for holding wine, generally made of glass. Some wines are fermented in the bottle, others are bottled only after fermentation. They come in a large variety of sizes, several named for Biblical kings and other figures. The standard bottle contains 750 ml,...

. During the 1630s, Digby owned a glassworks and manufactured wine bottles which were globular in shape with a high, tapered neck, a collar, and a punt. His manufacturing technique involved a coal furnace, made hotter than usual by the inclusion of a wind tunnel, and a higher ratio of sand to potash

Potash

Potash is the common name for various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water-soluble form. In some rare cases, potash can be formed with traces of organic materials such as plant remains, and this was the major historical source for it before the industrial era...

and lime

Lime (mineral)

Lime is a general term for calcium-containing inorganic materials, in which carbonates, oxides and hydroxides predominate. Strictly speaking, lime is calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide. It is also the name for a single mineral of the CaO composition, occurring very rarely...

than was customary. Digby's technique produced wine bottles which were stronger and more stable than most of their day, and which due to their translucent green or brown color protected the contents from light. During his exile and prison term, others claimed his technique as their own, but in 1662 Parliament recognized his claim to the invention as valid. Digby's bottles were also usually square which made them easier to stack.

External links

- A short extract from one of Digby's books on alchemy

Further reading

- Bligh, E W: Sir Kenelm Digby and his Venetia

- Fulton, John Farquhar: Sir Kenelm Digby; writer bibliophile & protagonist of William Harvey

- Peterson, R T: Sir Kenelm Digby

- Digby, Roy: Digby: The Gunpowder Plotter's Legacy ISBN 1-85756-520-7

- Gately, Ian: "Drink A Cultural History of Acohol" ISBN 978-1-592-40303-5 page #137