Josephinism

Encyclopedia

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II was Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Francis I...

(1765-1790). During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg Monarchy

Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg Monarchy covered the territories ruled by the junior Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg , and then by the successor House of Habsburg-Lorraine , between 1526 and 1867/1918. The Imperial capital was Vienna, except from 1583 to 1611, when it was moved to Prague...

(1780-1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms to remodel Austria in the form of the ideal Enlightened state. This provoked severe resistance from powerful forces within and outside of his empire, but ensured that he would be remembered as an “enlightened ruler

Enlightened absolutism

Enlightened absolutism is a form of absolute monarchy or despotism in which rulers were influenced by the Enlightenment. Enlightened monarchs embraced the principles of the Enlightenment, especially its emphasis upon rationality, and applied them to their territories...

.”

Joseph II

Born in 1741, Joseph was the son of Maria Theresa of AustriaMaria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina was the only female ruler of the Habsburg dominions and the last of the House of Habsburg. She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Mantua, Milan, Lodomeria and Galicia, the Austrian Netherlands and Parma...

and Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis I was Holy Roman Emperor and Grand Duke of Tuscany, though his wife effectively executed the real power of those positions. With his wife, Maria Theresa, he was the founder of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty...

. Given a rigorous education in the Enlightenment—with its emphasis on rationality, order, and careful organization in statecraft—it is little wonder that, viewing the often confused and complex morass of Habsburg administration in the crownlands of Austria, Bohemia, and Hungary, Joseph was deeply dissatisfied. He inherited the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in 1765, on the death of his father, but ruled the Habsburg lands only as “joint ruler” with his mother, the matriarch Maria Theresa, until 1780 .

1780-1787

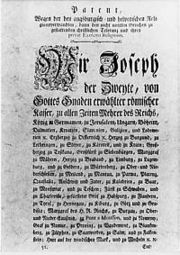

It was on the death of his mother in 1780 that Joseph II had the opportunity—free of any dominating hand—to pursue his own agenda. He intended a complete remodeling of Habsburg society in several different arenas. Issuing decrees and Patents, Joseph’s reforms were a conscious attempt to reorder the rule of his lands using Enlightened principles. At the heart of this “Josephinism” lay the idea of the unitary state, with a centralized, efficient government, rational and mostly secular society, with greater degrees of equality and freedom, and fewer arbitrary feudal institutions.Serfs, Lords, and the Robota

For many centuries, the majority of the population of Central Europe had lived as serfs, laboring under feudal obligations to Lords. On November 1, 1781, Joseph issued two Patents pertaining to Bohemia, which changed the serf-Lord relationship there by abolishing the use of fines and corporal punishment on serfs, and abolishing Lords’ control over serfs’ marriage, freedom of movement, and choice of occupation. The patents also allowed peasants to purchase hereditary ownership of the land that they worked. The nobility were hesitant to support Joseph’s edicts, however, and they were inconsistently applied .Throughout his reign, Joseph’s ultimate goal was one shared originally with his mother regarding policy toward the serfs. Robin Okey, in The Habsburg Monarchy, describes it as “[t]he replacement of the Robota [forced serf labor] system by the division of landed estates (including the demesne) among rent-paying tenants" . In 1783, Joseph’s advisor Franz Anton von Raab was instructed to extend this system to all lands owned directly by the Habsburg crown in Bohemia and Moravia .

Censorship and the Press

In February of 1781, Joseph issued an edict drastically reducing the power of state censorship over the press. Censorship was limited only to expression that (a) blasphemed against the church, (b) subverted the government, or (c) promoted immorality. Censorship was also taken out of the hands of local authorities and centralized under the Habsburg imperial government.Joseph was remarkably tolerant of dissenting speech—his censors banned only about 900 tracts published each year (down from 4,000 a year banned before his reign). One tract that even criticized him specifically, titled “The 42 Year-Old Ape,” was not banned .

Edicts of Tolerance

In May and October of 1781, Joseph issued Edicts which removed restrictions against the practice of Protestant and Orthodox Christian religion. In communities with large Protestant or Orthodox minorities, churches were allowed to be built, and social restrictions on vocations, economic activity, and education were removed .

In 1782, Joseph dismantled many of the legal barriers against Jews performing certain professions, and struck down the humiliating Jewish dress laws, Jewish-only taxes, and some restrictions on the movement of Jews. Personally, he remained somewhat anti-Semitic (deriding what he called “‘repellent Jewish characteristics’”). His decrees were also not comprehensive—Galicia, the Habsburg province with the largest Jewish minority, was not included in his reforms .

Catholic Church in Habsburg Lands

Regarding the Catholic church, Joseph was virulently opposed to what he called “contemplative” religious institutions — reclusive institutions that were seen as doing nothing positive for the community.By Joseph’s decree, Austrian bishops could not communicate directly with the Curia

Curia

A curia in early Roman times was a subdivision of the people, i.e. more or less a tribe, and with a metonymy it came to mean also the meeting place where the tribe discussed its affairs...

anymore. More than 500 of 1,188 monasteries in Austro-Slav lands (and a hundred more in Hungary) were dissolved, and 60 million florins

Austro-Hungarian gulden

The Gulden or forint was the currency of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire between 1754 and 1892 when it was replaced by the Krone/korona as part of the introduction of the gold standard. In Austria, the Gulden was initially divided into 60 Kreuzer, and in Hungary, the...

taken by the state. This wealth was used to create 1700 new parishes and welfare institutions .

The education of Priests was taken from the Church as well. Joseph established six state-run “General Seminaries.” In 1783, a Marriage Patent treated marriage as a civil contract rather than a religious institution .

When the Pope visited Austria in 1782, Joseph refused to rescind the majority of his decisions .

In 1783, the cathedral chapter of Passau opposed the nomination of a josephinist bishop and sent, first, an appeal to the emperor himself, which naturally was rejected; then an appeal to the Imperial Diet

Imperial Diet

Imperial Diet means the highest representative assembly in an empire, notably:* the historic institution of the Imperial Diet , either the estates in the Holy Roman Empire...

at Ratisbon, from which body, however, help could scarcely be expected. Assistance offered by Prussia was refused by Cardinal Firmian's successor, Bishop Joseph Franz Auersperg

Joseph Franz Auersperg

Josef Franz Anton Graf von Auersperg was an Austrian bishop, prince bishop of Passau and cardinal....

, an adherent of Josephinism. The Bishop of Passau and the majority of his cathedral chapter finally yielded in order to save the secular property of the diocese.

By an agreement of 4 July 1784, the confiscation of all the properties and rights belonging to the Diocese of Passau in Austria was annulled, and the tithes and revenues were restored to it. In return Passau gave up its diocesan rights and authority in Austria, including the provostship of Ardagger, and bound itself to pay 400,000 gulden ($900,000) -- afterwards reduced by the emperor to one-half -- toward the equipment of the new diocese.

There was nothing left for Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI , born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, was Pope from 1775 to 1799.-Early years:Braschi was born in Cesena...

to do but to give his consent, even though unwillingly, to the emperor's authoritarian act. The papal sanction of the agreement between Vienna and Passau was issued on 8 November 1784, and on 28 January 1785, appeared the Bull of Erection, "Romanus Pontifex

Romanus Pontifex

Romanus Pontifex is a papal bull written January 8, 1455 by Pope Nicholas V to King Afonso V of Portugal. As a follow-up to the Dum Diversas, it confirmed to the Crown of Portugal dominion over all lands discovered or conquered during the Age of Discovery. Along with encouraging the seizure of the...

".

As early as 1785 the Viennese ecclesiastical order of services was made obligatory, "in accordance with which all musical litanies, novenas, octaves, the ancient touching devotions, also processions, vespers, and similar ceremonies, were done away with." Numerous churches and chapels were closed and put to secular uses; the greater part of the old religious foundations and monasteries were suppressed as early as 1784.

Nevertheless there could be no durable peace with the bureaucratic civil authorities, and bishop Herberstein was repeatedly obliged to complain to the emperor of the tutelage in which the Church was kept, but the complaints bore little fruit.

Catholic Historians claimed that there was an alliance between Joseph and anti-clerical Freemasons.

Unity of Power, the Hungarian Crownlands, and the Austrian Netherlands

The pace of reform in Joseph’s empire was uneven, especially in the crownlands of Hungary. Joseph was reluctant to include Hungary in most of his reforms early in his reign.In 1784, Joseph brought the Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen from Pressburg, capital of Royal Hungary, to Vienna. This was a symbolic act, meant to emphasize a new unity between Hungary and the other crownlands. German replaced Latin as the official language of administration in Hungary . In 1785, Joseph extended his abolition of serfdom to Hungary, and a census of the crownland was ordered, in order to prepare it for an Austrian-style military draft .

In 1787, the “administrative streamlining” that had been applied to the rest of the Empire was nominally applied to Austrian possessions in the Netherlands, but this was fiercely opposed by Belgian nobles .

Domestic Resistance

Josephinism made many enemies inside the empire—from disaffected ecclesiastical authorities to noblemen. By the later years of his reign, disaffection with his sometimes radical policies was at a high, especially in the Austrian Netherlands and Hungary. Popular revolts and protests—led by nobles, seminary students, writers, and agents of Prussian King Frederick WilliamFrederick William II of Prussia

Frederick William II was the King of Prussia, reigning from 1786 until his death. He was in personal union the Prince-Elector of Brandenburg and the sovereign prince of the Principality of Neuchâtel.-Early life:...

—stirred throughout the Empire, prompting Joseph to tighten censorship of the press .

Before his death in 1790, Joseph was forced to rescind many of his administrative reforms. He returned the crown of St. Stephen to Buda in Hungary and promised to abide by the Hungarian constitution. Before he could actually be officially crowned “King of Hungary,” he died at the age of 49 .

Joseph’s brother and successor, Leopold II, reversed the course of the Empire by rescinding some Josephine reforms, but managed to preserve the unity of the Habsburg lands by showing a respect and sensitivity for local demands that Joseph lacked .

See also

- Josef Vratislav MonseJosef Vratislav MonseJosef Vratislav Monse was a Moravian lawyer and historian.He was a leading enlightenment figure in the Habsburg Monarchy and an early exponent of the Czech National Revival in Moravia. Monse played a key role in the development of modern Moravian Historiography...

- Suppression of the JesuitsSuppression of the JesuitsThe Suppression of the Jesuits in the Portuguese Empire, France, the Two Sicilies, Parma and the Spanish Empire by 1767 was a result of a series of political moves rather than a theological controversy. By the brief Dominus ac Redemptor Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society of Jesus...

- Enlightened absolutismEnlightened absolutismEnlightened absolutism is a form of absolute monarchy or despotism in which rulers were influenced by the Enlightenment. Enlightened monarchs embraced the principles of the Enlightenment, especially its emphasis upon rationality, and applied them to their territories...

- Wenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-RietbergWenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-RietbergWenzel Anton, Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg was a diplomat and statesman of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1764 he was made a prince of the Holy Roman Empire as Reichfürst von Kaunitz-Rietberg and in 1776 prince of the Kingdom of Bohemia.-Early life:Kaunitz was born in Vienna, one of 19 children of...

- Catholic EnlightenmentCatholic EnlightenmentThe term Catholic Enlightenment refers to a heterogeneous phenomenon in Ancien Régime Europe and Latin America. It stands for the Church policy pursued by a Catholic enlightened monarch and/or his ministers as well as for a "reform movement" within the Roman Catholic clergy to...

Sources

- Berenger, Jean. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1700-1918. Edinburgh: Addison Wesley, 1990.

- Ingrao, Charles W. The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618-1815. New York: Cambridge UP, 2000.

- Kann, Robert. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918. University of California P: Los Angeles, 1974.

- Okey, Robin. The Habsburg Monarchy c. 1765-1918. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2002.