Joseph Glanvill

Encyclopedia

Joseph Glanvill was an English

writer, philosopher, and clergyman. Not himself a scientist, he has been called "the most skillful apologist of the virtuosi", or in other words the leading propagandist for the approach of the English natural philosophers of the later 17th century.

household, and educated at Oxford University

, where he graduated B.A. from Exeter College

in 1655, M.A. from Lincoln College

in 1658.

Glanvill was made vicar of Frome

in 1662, and was a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1664. He was rector of the Abbey Church

at Bath from 1666 to 1680, and prebendary

of Worcester in 1678.

thinker. Latitudinarians generally respected the Cambridge Platonists

, and Glanvill was friendly with and much influenced by Henry More

, a leader in that group where Glanvill was a follower. It was Glanvill's style to seek out a "middle way" on contemporary philosophical issues. His writings display a variety of beliefs that may appear contradictory. There is discussion of Glanvill's thought and method in Basil Willey

's Seventeenth Century Background (1934).

and religious persecution

. It was a plea for religious toleration

, the scientific method

, and freedom of thought

. It also contained a tale that became the material for Matthew Arnold

's Victorian poem The Scholar Gipsy

.

Glanvill was at first a Cartesian

, but shifted his ground a little, engaging with scepticism and proposing a modification in Scepsis Scientifica (1665), a revision and expansion of The Vanity of Dogmatizing. It started with an explicit "Address to the Royal Society"; the Society responded by electing him as Fellow. He continued in a role of spokesman for his type of limited sceptical approach, and the Society's production of useful knowledge. As part of his programme, he argued for a plain use of language, undistorted as to definitions and reliance on metaphor

. He also advocated with Essay Concerning Preaching (1678) simple speech, rather than bluntness, in preaching, as Robert South

did, with hits at nonconformist sermons; he was quite aware that the term "plain" takes a great deal of unpacking.

In Essays on Several Important Subjects in Philosophy and Religion (1676) he wrote a significant essay The Agreement of Reason and Religion, aimed at least in part at nonconformism. Reason, in Glanvill's view, was incompatible with being a dissenter. In Antifanatickal Religion and Free Philosophy, another essay from the volume, he attacked the whole tradition of imaginative illumination in religion, going back to William Perkins, as founded on the denigration of reason. This essay has the subtitle Continuation of the New Atlantis

, and so connects with Francis Bacon

's utopia. In an allegory

, Glanvill placed the "Young Academicians", standing for the Cambridge Platonists, in the midst of intellectual troubles matching the religious upheavals seen in Britain. They coped by combining modern with ancient thought. Glanvill thought, however, that the world cannot be deduced from reason alone. Even the supernatural

cannot be solved from first principles and must be investigated empirically. As a result Glanvill attempted to investigate supposed supernatural incidents through interviews and examination of the scene of the events.

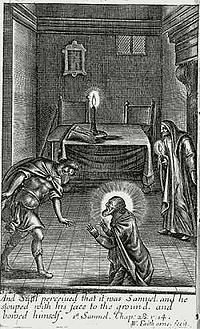

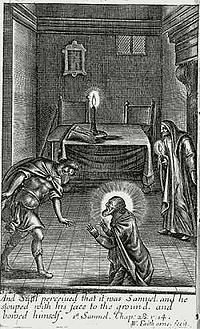

He is known also for Sadducismus Triumphatus

He is known also for Sadducismus Triumphatus

(1681), which decried scepticism about the existence and supernatural power of witchcraft

and contained a collection of seventeenth-century folklore about witches. It developed as a compendium (with multiple authorship) from Philosophical Considerations Touching the Being of Witches and Witchcraft (1666), addressed to Robert Hunt, a Justice of the Peace

active from the 1650s against witches in Somerset (where Glanvill had his living at Frome); the 1668 version A Blow at Modern Sadducism promoted the view that the judicial procedures such as Hunt's court offered should be taken as adequate tests of evidence, because to argue otherwise was to undermine society at its legal roots. His biographer Ferris Greenslet

attributed Glanvill's interest in the topic to a house party in February 1665 at Ragley Hall

, home of Lady Anne Conway, where other guests were More, Francis van Helmont, and Valentine Greatrakes

. In the matter of the Drummer of Tedworth, a report of poltergeist

-type activity from 1662-3, More and Glanvill had in fact already corresponded about it in 1663.

Sadducismus Triumphatus deeply influenced Cotton Mather

's Wonders of the Invisible World

(1693), written to justify the Salem witch trials

in the following year. It was also taken as a target when Francis Hutchinson

set down An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft (1718); both books made much of reports from Sweden, and included by Glanvill as editor, which had experienced a moral panic

about witchcraft after 1668.

Jonathan Israel

writes:

These and others (Richard Baxter

, Meric Casaubon

, George Sinclair) believed that the tide of scepticism on witchcraft, setting in strongly by about 1670, could be turned back by research and sifting of the evidence. Like More, Glanvill believed that the existence of spirits was well documented in the Bible, and that the denial of spirits and demons was the first step towards atheism

. Atheism led to rebellion and social chaos and therefore had to be overcome by science and the activities of the learned. Israel cites a letter from More to Glanvill, from 1678 and included in Sadducismus Triumphatus, in which he says that followers of Thomas Hobbes

and Baruch Spinoza

use scepticism about "spirits and angels" to undermine belief in the Scripture mentioning them.

, over the continuing value of the work of Aristotle

, the classical exponent of the middle way. In defending himself and the Royal Society, in Plus ultra, he attacked current teaching of medicine (physick), and in return was attacked by Henry Stubbe, in The Plus Ultra reduced to a Non Plus (1670). His views on Aristotle also led to an attack by Thomas White

, the Catholic priest known as Blacklo. In A Praefatory Answer to Mr. Henry Stubbe (1671) he defined the "philosophy of the virtuosi" cleanly: the "plain objects of sense" to be respected, as the locus of as much certainty as was available; the "suspension of assent" absent adequate proof; and the claim for the approach as "equally an adversary to scepticism and credulity". To White he denied being a sceptic. A contemporary view is that his approach was a species of rational fideism

.

His Philosophia Pia (1671) was explicitly about the connection between the "experimental philosophy" of the Royal Society and religion. It was a reply to a letter of Meric Casaubon, one of the Society's critics, to Peter du Moulin

. He used it to cast doubt on the roots of enthusiasm

, one of his main targets amongst the nonconformists. It also dealt with criticisms of Richard Baxter, who was another accusing the Society of an atheist tendency.

's short stories Ligeia

and A Descent into the Maelström

contain epigraphs ascribed to Glanvill.

Aleister Crowley

's book "Diary of a Drug Fiend

" opens with a direct quotation from Glanvill.

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

writer, philosopher, and clergyman. Not himself a scientist, he has been called "the most skillful apologist of the virtuosi", or in other words the leading propagandist for the approach of the English natural philosophers of the later 17th century.

Life

He was raised in a strict PuritanPuritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

household, and educated at Oxford University

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

, where he graduated B.A. from Exeter College

Exeter College, Oxford

Exeter College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England and the fourth oldest college of the University. The main entrance is on the east side of Turl Street...

in 1655, M.A. from Lincoln College

Lincoln College, Oxford

Lincoln College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is situated on Turl Street in central Oxford, backing onto Brasenose College and adjacent to Exeter College...

in 1658.

Glanvill was made vicar of Frome

Frome

Frome is a town and civil parish in northeast Somerset, England. Located at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, the town is built on uneven high ground, and centres around the River Frome. The town is approximately south of Bath, east of the county town, Taunton and west of London. In the 2001...

in 1662, and was a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1664. He was rector of the Abbey Church

Bath Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Bath, commonly known as Bath Abbey, is an Anglican parish church and a former Benedictine monastery in Bath, Somerset, England...

at Bath from 1666 to 1680, and prebendary

Prebendary

A prebendary is a post connected to an Anglican or Catholic cathedral or collegiate church and is a type of canon. Prebendaries have a role in the administration of the cathedral...

of Worcester in 1678.

Works and views

He was a LatitudinarianLatitudinarian

Latitudinarian was initially a pejorative term applied to a group of 17th-century English theologians who believed in conforming to official Church of England practices but who felt that matters of doctrine, liturgical practice, and ecclesiastical organization were of relatively little importance...

thinker. Latitudinarians generally respected the Cambridge Platonists

Cambridge Platonists

The Cambridge Platonists were a group of philosophers at Cambridge University in the middle of the 17th century .- Programme :...

, and Glanvill was friendly with and much influenced by Henry More

Henry More

Henry More FRS was an English philosopher of the Cambridge Platonist school.-Biography:Henry was born at Grantham and was schooled at The King's School, Grantham and at Eton College...

, a leader in that group where Glanvill was a follower. It was Glanvill's style to seek out a "middle way" on contemporary philosophical issues. His writings display a variety of beliefs that may appear contradictory. There is discussion of Glanvill's thought and method in Basil Willey

Basil Willey

Basil Willey was a professor of English literature at Cambridge University and a prolific author of well-written and scholarly works on English literature and intellectual history....

's Seventeenth Century Background (1934).

Rationality and plain talking

He was the author of The Vanity of Dogmatizing (editions from 1661), which attacked scholasticismScholasticism

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context...

and religious persecution

Religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

. It was a plea for religious toleration

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion or not to follow any...

, the scientific method

Scientific method

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

, and freedom of thought

Freedom of thought

Freedom of thought is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints....

. It also contained a tale that became the material for Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold was a British poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the famed headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, literary professor, and William Delafield Arnold, novelist and colonial administrator...

's Victorian poem The Scholar Gipsy

The Scholar Gipsy

"The Scholar Gipsy" is a poem by Matthew Arnold, based on a 17th century Oxford story found in Joseph Glanvill's The Vanity of Dogmatizing...

.

Glanvill was at first a Cartesian

Cartesianism

Cartesian means of or relating to the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes—from his name—Rene Des-Cartes. It may refer to:*Cartesian anxiety*Cartesian circle*Cartesian dualism...

, but shifted his ground a little, engaging with scepticism and proposing a modification in Scepsis Scientifica (1665), a revision and expansion of The Vanity of Dogmatizing. It started with an explicit "Address to the Royal Society"; the Society responded by electing him as Fellow. He continued in a role of spokesman for his type of limited sceptical approach, and the Society's production of useful knowledge. As part of his programme, he argued for a plain use of language, undistorted as to definitions and reliance on metaphor

Metaphor

A metaphor is a literary figure of speech that uses an image, story or tangible thing to represent a less tangible thing or some intangible quality or idea; e.g., "Her eyes were glistening jewels." Metaphor may also be used for any rhetorical figures of speech that achieve their effects via...

. He also advocated with Essay Concerning Preaching (1678) simple speech, rather than bluntness, in preaching, as Robert South

Robert South

Robert South was an English churchman, known for his combative preaching.-Early life:He was the son of Robert South, a London merchant, and Elizabeth Berry...

did, with hits at nonconformist sermons; he was quite aware that the term "plain" takes a great deal of unpacking.

In Essays on Several Important Subjects in Philosophy and Religion (1676) he wrote a significant essay The Agreement of Reason and Religion, aimed at least in part at nonconformism. Reason, in Glanvill's view, was incompatible with being a dissenter. In Antifanatickal Religion and Free Philosophy, another essay from the volume, he attacked the whole tradition of imaginative illumination in religion, going back to William Perkins, as founded on the denigration of reason. This essay has the subtitle Continuation of the New Atlantis

New Atlantis

New Atlantis and similar can mean:*New Atlantis, a novel by Sir Francis Bacon*The New Atlantis, founded in 2003, a journal about the social and political dimensions of science and technology...

, and so connects with Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

's utopia. In an allegory

Allegory

Allegory is a demonstrative form of representation explaining meaning other than the words that are spoken. Allegory communicates its message by means of symbolic figures, actions or symbolic representation...

, Glanvill placed the "Young Academicians", standing for the Cambridge Platonists, in the midst of intellectual troubles matching the religious upheavals seen in Britain. They coped by combining modern with ancient thought. Glanvill thought, however, that the world cannot be deduced from reason alone. Even the supernatural

Supernatural

The supernatural or is that which is not subject to the laws of nature, or more figuratively, that which is said to exist above and beyond nature...

cannot be solved from first principles and must be investigated empirically. As a result Glanvill attempted to investigate supposed supernatural incidents through interviews and examination of the scene of the events.

The supernatural

Sadducismus Triumphatus

Saducismus triumphatus is a book on witchcraft by Joseph Glanvill, published posthumously in England in 1681.The editor is presumed to have been Henry More, who certainly contributed to the volume; and topical material on witchcraft in Sweden was supplied by Anthony Horneck to later editions. By...

(1681), which decried scepticism about the existence and supernatural power of witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

and contained a collection of seventeenth-century folklore about witches. It developed as a compendium (with multiple authorship) from Philosophical Considerations Touching the Being of Witches and Witchcraft (1666), addressed to Robert Hunt, a Justice of the Peace

Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace is a puisne judicial officer elected or appointed by means of a commission to keep the peace. Depending on the jurisdiction, they might dispense summary justice or merely deal with local administrative applications in common law jurisdictions...

active from the 1650s against witches in Somerset (where Glanvill had his living at Frome); the 1668 version A Blow at Modern Sadducism promoted the view that the judicial procedures such as Hunt's court offered should be taken as adequate tests of evidence, because to argue otherwise was to undermine society at its legal roots. His biographer Ferris Greenslet

Ferris Greenslet

Ferris Lowell Greenslet was an American editor and writer.-Biography:Greenslet graduated from Wesleyan University in 1897, and was awarded the Ph.D. by Columbia University in 1900. He was an associate editor of the Atlantic Monthly, 1902-07. In 1910, he became a literary advisor and director of...

attributed Glanvill's interest in the topic to a house party in February 1665 at Ragley Hall

Ragley Hall

Ragley Hall is located south of Alcester, Warwickshire, eight miles west of Stratford-upon-Avon. It is the ancestral seat of the Marquess of Hertford and is one of the stately homes of England.-The present day:...

, home of Lady Anne Conway, where other guests were More, Francis van Helmont, and Valentine Greatrakes

Valentine Greatrakes

Valentine Greatrakes , also known as 'Greatorex' or 'The Stroker', was an Irish faith healer who toured England in 1666, claiming to cure people by the laying on of hands.-Biography:...

. In the matter of the Drummer of Tedworth, a report of poltergeist

Poltergeist

A poltergeist is a paranormal phenomenon which consists of events alluding to the manifestation of an imperceptible entity. Such manifestation typically includes inanimate objects moving or being thrown about, sentient noises and, on some occasions, physical attacks on those witnessing the...

-type activity from 1662-3, More and Glanvill had in fact already corresponded about it in 1663.

Sadducismus Triumphatus deeply influenced Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather, FRS was a socially and politically influential New England Puritan minister, prolific author and pamphleteer; he is often remembered for his role in the Salem witch trials...

's Wonders of the Invisible World

Wonders of the Invisible World

Wonders of the Invisible World was a book published in 1693 by Cotton Mather, defending Mather's role in the witchhunt conducted in Salem, Massachusetts, and espousing the belief that witchcraft was an evil magical power...

(1693), written to justify the Salem witch trials

Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings before county court trials to prosecute people accused of witchcraft in the counties of Essex, Suffolk, and Middlesex in colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693...

in the following year. It was also taken as a target when Francis Hutchinson

Francis Hutchinson

Francis Hutchinson was Bishop of Down and Connor and an opponent of witch-hunting.Hutchinson was born in Carsington, Wirksworth, Derbyshire, the second son of Mary and Edward Hutchinson or Hitchinson...

set down An Historical Essay Concerning Witchcraft (1718); both books made much of reports from Sweden, and included by Glanvill as editor, which had experienced a moral panic

Moral panic

A moral panic is the intensity of feeling expressed in a population about an issue that appears to threaten the social order. According to Stanley Cohen, author of Folk Devils and Moral Panics and credited creator of the term, a moral panic occurs when "[a] condition, episode, person or group of...

about witchcraft after 1668.

Jonathan Israel

Jonathan Israel

Professor Jonathan Irvine Israel is a British writer on Dutch history, the Age of Enlightenment and European Jewry. Israel was appointed the Modern European History Professor in the School of Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton Township, New Jersey, U.S...

writes:

These and others (Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter was an English Puritan church leader, poet, hymn-writer, theologian, and controversialist. Dean Stanley called him "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". After some false starts, he made his reputation by his ministry at Kidderminster, and at around the same time began a long...

, Meric Casaubon

Méric Casaubon

Méric Casaubon , son of Isaac Casaubon, was a French-English classical scholar...

, George Sinclair) believed that the tide of scepticism on witchcraft, setting in strongly by about 1670, could be turned back by research and sifting of the evidence. Like More, Glanvill believed that the existence of spirits was well documented in the Bible, and that the denial of spirits and demons was the first step towards atheism

Atheism

Atheism is, in a broad sense, the rejection of belief in the existence of deities. In a narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there are no deities...

. Atheism led to rebellion and social chaos and therefore had to be overcome by science and the activities of the learned. Israel cites a letter from More to Glanvill, from 1678 and included in Sadducismus Triumphatus, in which he says that followers of Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

and Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch de Spinoza and later Benedict de Spinoza was a Dutch Jewish philosopher. Revealing considerable scientific aptitude, the breadth and importance of Spinoza's work was not fully realized until years after his death...

use scepticism about "spirits and angels" to undermine belief in the Scripture mentioning them.

Atheism, scepticism and Aristotle

His views did not prevent Glanvill himself being charged with atheism. This happened after he engaged in a controversy with Robert CrosseRobert Crosse

Robert Crosse was an English puritan theologian.-Life:He was son of William Crosse of Dunster, Somerset. He entered Lincoln College, Oxford, in 1621, obtained a fellowship in 1627, graduated in arts, and in 1637 proceeded B.D...

, over the continuing value of the work of Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, the classical exponent of the middle way. In defending himself and the Royal Society, in Plus ultra, he attacked current teaching of medicine (physick), and in return was attacked by Henry Stubbe, in The Plus Ultra reduced to a Non Plus (1670). His views on Aristotle also led to an attack by Thomas White

Thomas White (scholar)

Thomas White was an English Roman Catholic priest and scholar, known as a theologian, censured by the Inquisition, and also as a philosopher contributing to scientific and political debates.-Life:...

, the Catholic priest known as Blacklo. In A Praefatory Answer to Mr. Henry Stubbe (1671) he defined the "philosophy of the virtuosi" cleanly: the "plain objects of sense" to be respected, as the locus of as much certainty as was available; the "suspension of assent" absent adequate proof; and the claim for the approach as "equally an adversary to scepticism and credulity". To White he denied being a sceptic. A contemporary view is that his approach was a species of rational fideism

Rational fideism

Rational fideism is the philosophical view that considers faith to be precursor for any reliable knowledge. Whether one considers rationalism or empiricism, either of them ultimately tends to belief in reason or experience respectively as the absolute basis for their methods. Thus, faith is basic...

.

His Philosophia Pia (1671) was explicitly about the connection between the "experimental philosophy" of the Royal Society and religion. It was a reply to a letter of Meric Casaubon, one of the Society's critics, to Peter du Moulin

Peter du Moulin

Peter du Moulin was a French-English Anglican clergyman, son of the Huguenot pastor Pierre du Moulin and brother of Lewis du Moulin. He was the anonymous author of Regii sanguinis clamor ad coelum adversus paricidas Anglicanos, published at The Hague in 1652, a royalist work defending Salmasius...

. He used it to cast doubt on the roots of enthusiasm

Enthusiasm

Enthusiasm originally meant inspiration or possession by a divine afflatus or by the presence of a god. Johnson's Dictionary, the first comprehensive dictionary of the English language, defines enthusiasm as "a vain belief of private revelation; a vain confidence of divine favour or...

, one of his main targets amongst the nonconformists. It also dealt with criticisms of Richard Baxter, who was another accusing the Society of an atheist tendency.

In literature

Edgar Allan PoeEdgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective...

's short stories Ligeia

Ligeia

"Ligeia" is an early short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1838. The story follows an unnamed narrator and his wife Ligeia, a beautiful and intelligent raven-haired woman. She falls ill, composes "The Conqueror Worm", and quotes lines attributed to Joseph Glanvill ...

and A Descent into the Maelström

A Descent into the Maelstrom

"A Descent into the Maelström" is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe. In the tale, a man recounts how he survived a shipwreck and a whirlpool. It has been grouped with Poe's tales of ratiocination and also labeled an early form of science fiction.-Plot:...

contain epigraphs ascribed to Glanvill.

Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley , born Edward Alexander Crowley, and also known as both Frater Perdurabo and The Great Beast, was an influential English occultist, astrologer, mystic and ceremonial magician, responsible for founding the religious philosophy of Thelema. He was also successful in various other...

's book "Diary of a Drug Fiend

Diary of a Drug Fiend

Diary of a Drug Fiend, published in 1922, was occult writer and mystic Aleister Crowley's first published novel, and is also reportedly the earliest known reference to the Abbey of Thelema in Sicily.-Plot introduction:...

" opens with a direct quotation from Glanvill.

Further reading

- Richard H. Popkin, Joseph Glanvill: A Precursor of David Hume, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Apr., 1953), pp. 292–303

- Jackson I. Cope, Joseph Glanvill, Anglican Apologist: Old Ideas and New Style in the Restoration, PMLA, Vol. 69, No. 1 (Mar., 1954), pp. 223–250

- Richard H. Popkin, The Development of the Philosophical Reputation of Joseph Glanvill, Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Apr., 1954), pp. 305–311

- Dorothea Krook, Two Baconians: Robert Boyle and Joseph Glanvill, Huntington Library Quarterly 18 (1955): 261–78

- Robert M. Burns (1981), The Great Debate on Miracles: From Joseph Glanvill to David Hume

- Sascha Talmor (1981), Glanvill: The Uses and Abuses of Skepticism

- Richard H. Popkin (1992), The Third Force in Seventeenth-century Thought, Ch. 15 The Scepticism of Joseph Glanvill