John Ericsson

Encyclopedia

John Ericsson was a Swedish-American inventor and mechanical

engineer

, as was his brother Nils Ericson

. He was born at Långbanshyttan in Värmland

, Sweden

, but primarily came to be active in England and the United States

. He is remembered best for designing the steam locomotive

Novelty

(in partnership with engineer John Braithwaite) and the ironclad USS Monitor

.

in Värmland had lost money in speculations and had to move his family from Värmland to Forsvik in 1810. There he worked as a 'director of blastings' during the excavation of the Swedish Göta Canal

. The extraordinary skills of the two brothers were discovered by Baltzar von Platen

, the architect of the Göta Canal. The two brothers were dubbed cadets of mechanics of the Swedish Royal Navy and engaged as trainees at the canal enterprise. At the age of fourteen, John was already working independently as a surveyor. His assistant had to carry a footstool for him to reach the instruments during surveying

work.

At the age of seventeen he joined the Swedish army

in Jämtland

, serving in the Jämtland Field Ranger Regiment, as a Second Lieutenant, but was soon promoted to Lieutenant

. He was sent to northern Sweden to do surveying, and in his spare time he constructed a heat engine

which used the fumes from the fire instead of steam as a propellant. His skill and interest in mechanics made him resign from the army and move to England

in 1826. However his heat engine was not a success, as his prototype was designed to burn birch

wood and would not work well with coal

(the main fuel used in England).

Notwithstanding the disappointment, he invented several other mechanisms instead based on steam

Notwithstanding the disappointment, he invented several other mechanisms instead based on steam

, improving the heating process by adding fans to increase oxygen

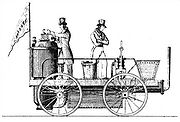

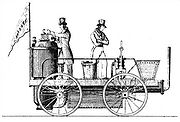

supply to the fire bed. In 1829 he and John Braithwaite built "Novelty"

for the Rainhill Trials

arranged by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

. It proved considerably faster than the other entrants but suffered recurring boiler problems, and the competition was won by English engineers George

and Robert Stephenson

with Rocket

.

Two further engines were built by Braithwaite and Ericsson, named William IV

and Queen Adelaide after the new king and queen. These were generally larger and more robust than Novelty and differed in several details (for example it is thought that a different design of blower was used which was an ‘Induced Draught’ type, sucking the gases from the fire). The pair ran trials on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

but the railway declined to purchase the new designs.

Their innovative steam fire engine proved an outstanding technical success by helping to quell the memorable Argyll Rooms fire on 5 February 1830 (where it worked for five hours when the other engines were frozen up), but was met with resistance from London's established 'Fire Laddies' and municipal authorities. An engine Ericsson constructed for Sir John Franklin

's use failed under the Antarctic conditions for which, out of Franklin's desire to conceal his destination, it had not been designed. At this stage of Ercisson's career the most successful and enduring of his inventions was the steam condenser, which allowed a steamer to produce fresh water for its boilers while at sea. His 'deep sea lead,' a pressure-activated fathometer was another minor, but enduring success.

The commercial failure and development costs of some of the machines devised and built by Ericsson during this period put him into debtors' prison for an interval. At this time he also married 19-year-old Amelia Byam, a marriage that was nothing but a huge disaster and ended in the couple's separation until Amelia's death.

He then improved the ship design with two screw-propeller

He then improved the ship design with two screw-propeller

s moving in different directions (as opposed to earlier tests with this technology, which used a single screw). However, the Admiralty

disapproved of the invention, which led to the fortunate contact with the encouraging American captain Robert Stockton who had Ericsson design a propeller steamer for him and told him to bring his invention to the United States of America, as it would supposedly be more welcomed in that place. As a result, Ericsson moved to New York

in 1839. Stockton's plan was for Ericsson to oversee the development of a new class of frigate

with Stockton using his considerable political connections to grease the wheels. Finally, after the succession to the Presidency by John Tyler

, funds were allocated for a new design. Unfortunately they only received funding for a 700-ton sloop

instead of a frigate. The sloop eventually became the USS Princeton

, named after Stockton's hometown.

The ship took about three years to complete and was perhaps the most advanced warship of its time. In addition to twin screw propellers, it was originally designed to mount a 12-inch muzzle loading gun on a revolving pedestal. The gun had also been designed by Ericsson and used the hoop

construction method to pre-tension the breech

, adding to its strength and safely allowing the use of a larger charge. Other innovations on the ship design included a collapsible funnel and an improved recoil system.

The relations between Ericsson and Stockton had grown tense over time and, nearing the completion of the ship, Stockton began working to force Ericsson out of the project. Stockton carefully avoided letting outsiders know that Ericsson was the primary inventor. Stockton attempted to claim as much credit for himself as possible, even designing a second 12-inch gun to be mounted on the Princeton. Unfortunately, not understanding the design of the first gun (originally name "The Orator", renamed by Stockton to "The Oregon"), the second gun was fatally flawed.

When the ship was initially launched it was a tremendous success. On October 20, 1843 Princeton

won a speed competition against the paddle-steamer SS Great Western

, which had until then been regarded as the fastest steamer afloat. Unfortunately, during a firing demonstration of Stockton's gun the breech broke

, killing the US Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur

and the Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer, as well as six others. Stockton attempted to deflect blame onto Ericsson with moderate success despite the fact that Ericsson's gun was sound and it was Stockton's gun that had failed. Stockton also refused to pay Ericsson and, using his political connections, Stockton managed to block the Navy from paying him. These actions led to Ericsson's deep resentment toward the US Navy.

and soon a mutual attachment developed between the two, and rarely thereafter did Ericsson or DeLamater enter upon a business venture without first consulting the other." Personally, their friendship never faltered, though strained by the pressures of business and Ericsson's quick temper, DeLamater called Ericsson "John" and Ericsson called DeLamater by his middle nickname "Harry", intimacies almost unknown in Ericsson's other relationships. In time, the DeLamater Iron Works became known as the Asylum where Capt Ericsson had free rein to experiment and attempt new feats. The Iron Witch was next constructed, the first iron steamboat. The first hot-air invention of Capt Ericsson was first introduced in the ship Ericsson, built entirely by DeLamater. The DeLamater Iron Works also launched the first submarine boat, first self propelled torpedo, and first torpedo boat. When DeLamater died on February 2, 1889, Ericsson could not be consoled. Ericsson's death one month later was not surprising to his close friends and acquaintances."

in the 1820s which used hot air, caloric in the scientific parlance of the day, instead of steam as a propellant. A similar device had been patented in 1816 by the Reverend Robert Stirling

, whose technical priority of invention provides the usual term 'Stirling Engine' for the device. Ericsson's engine was not initially successful due to the differences in combustion temperatures between Swedish wood and British coal. In spite of his setbacks, Ericsson was awarded the Rumford Prize

of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1862 for his invention. In his later years, the caloric engine would render Ericsson comfortably wealthy, as its boilerless design made it a much safer and more practical means of power for small industry than steam engines. Ericsson's incorporation of a 'regenerator' heat sink for his engine made it tremendously fuel-efficient.

with drawings of iron-clad armored battle ships with a dome

-shaped gun tower, and even though the French emperor praised this invention, he did nothing to bring it to practical application.

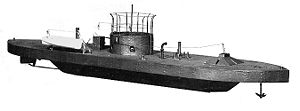

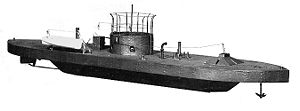

Shortly after the American Civil War

Shortly after the American Civil War

broke out in 1861, the Confederacy

began constructing an ironclad ram upon the hull of the USS Merrimack

which had been partially burned by Federal troops before it was captured by forces loyal to the Commonwealth of Virginia. Nearly concurrently, the United States Congress

had recommended in August 1861 that armored ships be built for the American Navy. Ericsson still had a dislike for the U.S. Navy, but he was nevertheless convinced by Cornelius Scranton Bushnell

to submit an ironclad ship design to them. Ericsson later presented drawings of the USS Monitor

, a novel design of armored ship which included a rotating turret housing a pair of large cannons. Despite controversy over the unique design, the keel was eventually laid down and the ironclad was launched on March 6, 1862. The ship went from plans to launch in approximately 100 days, an amazing achievement.

On March 8, the former USS Merrimack, rechristened the CSS Virginia

, was wreaking havoc on the wooden Union Blockading Squadron in Virginia, sinking several major warships, including the USS Cumberland

. The Monitor appeared the next day, initiating the first battle between ironclad warships on March 9, 1862 at Hampton Roads

, Virginia

. The battle ended in a tactical stalemate between the two ironclad warships, neither of which appeared capable of sinking the other, but strategically saved the remaining Union fleet from defeat. After this, numerous monitors were built for the Union, including twin turret versions, and contributed greatly to the naval victory of the Union over the rebellious states. Despite their low draft and subsequent problems in navigating in high seas, many basic design elements of the Monitor class were copied in future warships by other designers and navies. The rotating turret in particular is considered one of the greatest technological advances in naval history, still found on warships today.

Later Ericsson designed other naval vessels and weapons, including a type of torpedo

and a Destroyer, a torpedo boat

that could fire a cannon from an underwater port. He also provided some technical support for John Philip Holland

in his early submarine experiments. In the book Contributions to the Centennial Exhibition (1877, reprinted 1976) he presented his "sun engines", which collected solar heat for a hot air engine

. One of these designs earned Ericsson additional income after being converted to work as a methane gas engine.

Although none of his inventions created any large industries, he is regarded as one of the most influential mechanical engineers ever. After his death in 1889 his remains were brought from the United States to Stockholm

by USS Baltimore

; his final resting place is at Filipstad

, in Värmland

.

Monuments in honor of John Ericsson have been erected at:

Monuments in honor of John Ericsson have been erected at:

For ships named in his honor, see:

Organizations:

Mechanics

Mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the behavior of physical bodies when subjected to forces or displacements, and the subsequent effects of the bodies on their environment....

engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

, as was his brother Nils Ericson

Nils Ericson

Friherre Nils Ericson was a Swedish mechanical engineer...

. He was born at Långbanshyttan in Värmland

Värmland

' is a historical province or landskap in the west of middle Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Dalsland, Dalarna, Västmanland and Närke. It is also bounded by Norway in the west. Latin name versions are Vermelandia and Wermelandia. Although the province's land originally was Götaland, the...

, Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, but primarily came to be active in England and the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. He is remembered best for designing the steam locomotive

Steam locomotive

A steam locomotive is a railway locomotive that produces its power through a steam engine. These locomotives are fueled by burning some combustible material, usually coal, wood or oil, to produce steam in a boiler, which drives the steam engine...

Novelty

Novelty

Novelty is the quality of being new, or following from that, of being striking, original or unusual. Although it may be said to have an objective dimension Novelty (derived from Latin word novus for "new") is the quality of being new, or following from that, of being striking, original or unusual....

(in partnership with engineer John Braithwaite) and the ironclad USS Monitor

USS Monitor

USS Monitor was the first ironclad warship commissioned by the United States Navy during the American Civil War. She is most famous for her participation in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, the first-ever battle fought between two ironclads...

.

Early career

John's and Nils's father Olaf Ericsson who worked as the supervisor for a mineMining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the earth, from an ore body, vein or seam. The term also includes the removal of soil. Materials recovered by mining include base metals, precious metals, iron, uranium, coal, diamonds, limestone, oil shale, rock...

in Värmland had lost money in speculations and had to move his family from Värmland to Forsvik in 1810. There he worked as a 'director of blastings' during the excavation of the Swedish Göta Canal

Göta Canal

The Göta Canal is a Swedish canal constructed in the early 19th century. It formed the backbone of a waterway stretching some 382 miles , linking a number of lakes and rivers to provide a route from Gothenburg on the west coast to Söderköping on the Baltic Sea via the river Göta älv and the...

. The extraordinary skills of the two brothers were discovered by Baltzar von Platen

Baltzar von Platen (1766-1829)

Count Baltzar Bogislaus von Platen was a Swedish naval officer and statesman. He was born on the island of Rügen to Filip Julius Bernhard von Platen, Field Marshal and the Swedish Governor General of Pomerania, and Regina Juliana von Usedom.-Swedish Navy:At age 13 Baltzar entered the Royal...

, the architect of the Göta Canal. The two brothers were dubbed cadets of mechanics of the Swedish Royal Navy and engaged as trainees at the canal enterprise. At the age of fourteen, John was already working independently as a surveyor. His assistant had to carry a footstool for him to reach the instruments during surveying

Surveying

See Also: Public Land Survey SystemSurveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, and science of accurately determining the terrestrial or three-dimensional position of points and the distances and angles between them...

work.

At the age of seventeen he joined the Swedish army

Swedish Army

The Swedish Army is one of the oldest standing armies in the world and a branch of the Swedish Armed Forces; it is in charge of land operations. General Sverker Göranson is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Army.- Organization :...

in Jämtland

Jämtland

Jämtland or Jamtland is a historical province or landskap in the center of Sweden in northern Europe. It borders to Härjedalen and Medelpad in the south, Ångermanland in the east, Lapland in the north and Trøndelag and Norway in the west...

, serving in the Jämtland Field Ranger Regiment, as a Second Lieutenant, but was soon promoted to Lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

. He was sent to northern Sweden to do surveying, and in his spare time he constructed a heat engine

Heat engine

In thermodynamics, a heat engine is a system that performs the conversion of heat or thermal energy to mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a high temperature state to a lower temperature state. A heat "source" generates thermal energy that brings the working substance...

which used the fumes from the fire instead of steam as a propellant. His skill and interest in mechanics made him resign from the army and move to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

in 1826. However his heat engine was not a success, as his prototype was designed to burn birch

Birch

Birch is a tree or shrub of the genus Betula , in the family Betulaceae, closely related to the beech/oak family, Fagaceae. The Betula genus contains 30–60 known taxa...

wood and would not work well with coal

Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

(the main fuel used in England).

Steam

Steam is the technical term for water vapor, the gaseous phase of water, which is formed when water boils. In common language it is often used to refer to the visible mist of water droplets formed as this water vapor condenses in the presence of cooler air...

, improving the heating process by adding fans to increase oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

supply to the fire bed. In 1829 he and John Braithwaite built "Novelty"

Novelty (locomotive)

Novelty was an early steam locomotive built by John Ericsson and John Braithwaite to take part in the Rainhill Trials in 1829.It was an 0-2-2WT locomotive and is now regarded as the very first tank engine. It had a unique design of boiler and a number of other novel design features...

for the Rainhill Trials

Rainhill Trials

The Rainhill Trials were an important competition in the early days of steam locomotive railways, run in October 1829 in Rainhill, Lancashire for the nearly completed Liverpool and Manchester Railway....

arranged by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world's first inter-city passenger railway in which all the trains were timetabled and were hauled for most of the distance solely by steam locomotives. The line opened on 15 September 1830 and ran between the cities of Liverpool and Manchester in North...

. It proved considerably faster than the other entrants but suffered recurring boiler problems, and the competition was won by English engineers George

George Stephenson

George Stephenson was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer who built the first public railway line in the world to use steam locomotives...

and Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS was an English civil engineer. He was the only son of George Stephenson, the famed locomotive builder and railway engineer; many of the achievements popularly credited to his father were actually the joint efforts of father and son.-Early life :He was born on the 16th of...

with Rocket

Stephenson's Rocket

Stephenson's Rocket was an early steam locomotive of 0-2-2 wheel arrangement, built in Newcastle Upon Tyne at the Forth Street Works of Robert Stephenson and Company in 1829.- Design innovations :...

.

Two further engines were built by Braithwaite and Ericsson, named William IV

William IV of the United Kingdom

William IV was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death...

and Queen Adelaide after the new king and queen. These were generally larger and more robust than Novelty and differed in several details (for example it is thought that a different design of blower was used which was an ‘Induced Draught’ type, sucking the gases from the fire). The pair ran trials on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the world's first inter-city passenger railway in which all the trains were timetabled and were hauled for most of the distance solely by steam locomotives. The line opened on 15 September 1830 and ran between the cities of Liverpool and Manchester in North...

but the railway declined to purchase the new designs.

Their innovative steam fire engine proved an outstanding technical success by helping to quell the memorable Argyll Rooms fire on 5 February 1830 (where it worked for five hours when the other engines were frozen up), but was met with resistance from London's established 'Fire Laddies' and municipal authorities. An engine Ericsson constructed for Sir John Franklin

John Franklin

Rear-Admiral Sir John Franklin KCH FRGS RN was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. Franklin also served as governor of Tasmania for several years. In his last expedition, he disappeared while attempting to chart and navigate a section of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic...

's use failed under the Antarctic conditions for which, out of Franklin's desire to conceal his destination, it had not been designed. At this stage of Ercisson's career the most successful and enduring of his inventions was the steam condenser, which allowed a steamer to produce fresh water for its boilers while at sea. His 'deep sea lead,' a pressure-activated fathometer was another minor, but enduring success.

The commercial failure and development costs of some of the machines devised and built by Ericsson during this period put him into debtors' prison for an interval. At this time he also married 19-year-old Amelia Byam, a marriage that was nothing but a huge disaster and ended in the couple's separation until Amelia's death.

Propeller design

Propeller

A propeller is a type of fan that transmits power by converting rotational motion into thrust. A pressure difference is produced between the forward and rear surfaces of the airfoil-shaped blade, and a fluid is accelerated behind the blade. Propeller dynamics can be modeled by both Bernoulli's...

s moving in different directions (as opposed to earlier tests with this technology, which used a single screw). However, the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

disapproved of the invention, which led to the fortunate contact with the encouraging American captain Robert Stockton who had Ericsson design a propeller steamer for him and told him to bring his invention to the United States of America, as it would supposedly be more welcomed in that place. As a result, Ericsson moved to New York

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

in 1839. Stockton's plan was for Ericsson to oversee the development of a new class of frigate

Frigate

A frigate is any of several types of warship, the term having been used for ships of various sizes and roles over the last few centuries.In the 17th century, the term was used for any warship built for speed and maneuverability, the description often used being "frigate-built"...

with Stockton using his considerable political connections to grease the wheels. Finally, after the succession to the Presidency by John Tyler

John Tyler

John Tyler was the tenth President of the United States . A native of Virginia, Tyler served as a state legislator, governor, U.S. representative, and U.S. senator before being elected Vice President . He was the first to succeed to the office of President following the death of a predecessor...

, funds were allocated for a new design. Unfortunately they only received funding for a 700-ton sloop

Sloop

A sloop is a sail boat with a fore-and-aft rig and a single mast farther forward than the mast of a cutter....

instead of a frigate. The sloop eventually became the USS Princeton

USS Princeton (1843)

The first Princeton was the first screw steam warship in the United States Navy. She was launched in 1843, decommissioned in 1847, and broken up in 1849....

, named after Stockton's hometown.

The ship took about three years to complete and was perhaps the most advanced warship of its time. In addition to twin screw propellers, it was originally designed to mount a 12-inch muzzle loading gun on a revolving pedestal. The gun had also been designed by Ericsson and used the hoop

Hoop gun

A hoop gun is a gun production technique that uses multiple layers of tubes to form a built-up gun. The innermost tube has one or more extra tubes wrapped around the main tube. These outer tubes are preheated before they are slid into position. As the outer tubes cool they naturally contract. This...

construction method to pre-tension the breech

Breech-loading weapon

A breech-loading weapon is a firearm in which the cartridge or shell is inserted or loaded into a chamber integral to the rear portion of a barrel....

, adding to its strength and safely allowing the use of a larger charge. Other innovations on the ship design included a collapsible funnel and an improved recoil system.

The relations between Ericsson and Stockton had grown tense over time and, nearing the completion of the ship, Stockton began working to force Ericsson out of the project. Stockton carefully avoided letting outsiders know that Ericsson was the primary inventor. Stockton attempted to claim as much credit for himself as possible, even designing a second 12-inch gun to be mounted on the Princeton. Unfortunately, not understanding the design of the first gun (originally name "The Orator", renamed by Stockton to "The Oregon"), the second gun was fatally flawed.

When the ship was initially launched it was a tremendous success. On October 20, 1843 Princeton

USS Princeton (1843)

The first Princeton was the first screw steam warship in the United States Navy. She was launched in 1843, decommissioned in 1847, and broken up in 1849....

won a speed competition against the paddle-steamer SS Great Western

SS Great Western

SS Great Western of 1838, was an oak-hulled paddle-wheel steamship; the first purpose-built for crossing the Atlantic and the initial unit of the Great Western Steamship Company. Designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Great Western proved satisfactory in service and was the model for all successful...

, which had until then been regarded as the fastest steamer afloat. Unfortunately, during a firing demonstration of Stockton's gun the breech broke

USS Princeton Disaster of 1844

The USS Princeton Disaster of 1844 occurred on February 28 aboard the newly built USS Princeton when one of the ship's long guns, the "Peacemaker", then the world's longest naval gun, exploded during a display of the ship...

, killing the US Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur

Abel P. Upshur

Abel Parker Upshur was an American lawyer, judge and politician from Virginia. Upshur was active in Virginia state politics and later served as Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of State during the Whig administration of President John Tyler...

and the Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer, as well as six others. Stockton attempted to deflect blame onto Ericsson with moderate success despite the fact that Ericsson's gun was sound and it was Stockton's gun that had failed. Stockton also refused to pay Ericsson and, using his political connections, Stockton managed to block the Navy from paying him. These actions led to Ericsson's deep resentment toward the US Navy.

Friendship with Cornelius H. DeLamater

When Ericsson arrived from England and settled in New York, he was persuaded by Samuel Risley of Greenwich Village to give his work to the Phoenix Foundry. There he met Cornelius H. DeLamaterCornelius H. DeLamater

Cornelius Henry DeLamater was an industrialist who owned DeLamater Iron Works in New York City. The steam boilers and machinery for the ironclad was built in DeLamater's foundry during the Civil War. Swedish marine engineer and inventor John Ericsson considered DeLamater his closest, most...

and soon a mutual attachment developed between the two, and rarely thereafter did Ericsson or DeLamater enter upon a business venture without first consulting the other." Personally, their friendship never faltered, though strained by the pressures of business and Ericsson's quick temper, DeLamater called Ericsson "John" and Ericsson called DeLamater by his middle nickname "Harry", intimacies almost unknown in Ericsson's other relationships. In time, the DeLamater Iron Works became known as the Asylum where Capt Ericsson had free rein to experiment and attempt new feats. The Iron Witch was next constructed, the first iron steamboat. The first hot-air invention of Capt Ericsson was first introduced in the ship Ericsson, built entirely by DeLamater. The DeLamater Iron Works also launched the first submarine boat, first self propelled torpedo, and first torpedo boat. When DeLamater died on February 2, 1889, Ericsson could not be consoled. Ericsson's death one month later was not surprising to his close friends and acquaintances."

Hot air engine

Ericsson then proceeded to invent independently the caloric, or hot air engineHot air engine

A hot air engine is any heat engine which uses the expansion and contraction of air under the influence of a temperature change to convert thermal energy into mechanical work...

in the 1820s which used hot air, caloric in the scientific parlance of the day, instead of steam as a propellant. A similar device had been patented in 1816 by the Reverend Robert Stirling

Robert Stirling

The Reverend Dr Robert Stirling was a Scottish clergyman, and inventor of the stirling engine.- Biography :Stirling was born at Cloag Farm near Methven, Perthshire, the third of eight children...

, whose technical priority of invention provides the usual term 'Stirling Engine' for the device. Ericsson's engine was not initially successful due to the differences in combustion temperatures between Swedish wood and British coal. In spite of his setbacks, Ericsson was awarded the Rumford Prize

Rumford Prize

Founded in 1796, the Rumford Prize, awarded by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, is one of the oldest scientific prizes in the United States. The prize recognizes contributions by scientists to the fields of heat and light...

of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1862 for his invention. In his later years, the caloric engine would render Ericsson comfortably wealthy, as its boilerless design made it a much safer and more practical means of power for small industry than steam engines. Ericsson's incorporation of a 'regenerator' heat sink for his engine made it tremendously fuel-efficient.

Ship design

On September 26, 1854 Ericsson presented Napoleon III of FranceNapoleon III of France

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was the President of the French Second Republic and as Napoleon III, the ruler of the Second French Empire. He was the nephew and heir of Napoleon I, christened as Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte...

with drawings of iron-clad armored battle ships with a dome

Dome

A dome is a structural element of architecture that resembles the hollow upper half of a sphere. Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage extending into prehistory....

-shaped gun tower, and even though the French emperor praised this invention, he did nothing to bring it to practical application.

USS Monitor

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

broke out in 1861, the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

began constructing an ironclad ram upon the hull of the USS Merrimack

USS Merrimack (1855)

USS Merrimack was a frigate and sailing vessel of the United States Navy, best known as the hull upon which the ironclad warship, CSS Virginia was constructed during the American Civil War...

which had been partially burned by Federal troops before it was captured by forces loyal to the Commonwealth of Virginia. Nearly concurrently, the United States Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

had recommended in August 1861 that armored ships be built for the American Navy. Ericsson still had a dislike for the U.S. Navy, but he was nevertheless convinced by Cornelius Scranton Bushnell

Cornelius Scranton Bushnell

Cornelius Scranton Bushnell was an American railroad executive and shipbuilder who was instrumental in developing ironclad ships for the Union Navy during the American Civil War.-Background:...

to submit an ironclad ship design to them. Ericsson later presented drawings of the USS Monitor

USS Monitor

USS Monitor was the first ironclad warship commissioned by the United States Navy during the American Civil War. She is most famous for her participation in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, the first-ever battle fought between two ironclads...

, a novel design of armored ship which included a rotating turret housing a pair of large cannons. Despite controversy over the unique design, the keel was eventually laid down and the ironclad was launched on March 6, 1862. The ship went from plans to launch in approximately 100 days, an amazing achievement.

On March 8, the former USS Merrimack, rechristened the CSS Virginia

CSS Virginia

CSS Virginia was the first steam-powered ironclad warship of the Confederate States Navy, built during the first year of the American Civil War; she was constructed as a casemate ironclad using the raised and cut down original lower hull and steam engines of the scuttled . Virginia was one of the...

, was wreaking havoc on the wooden Union Blockading Squadron in Virginia, sinking several major warships, including the USS Cumberland

USS Cumberland

Three ships of the United States Navy have been named Cumberland, after the Cumberland River.*The , a 50-gun sailing frigate launched in 1842.*The , a steel-hulled sailing bark, was launched 17 August 1904....

. The Monitor appeared the next day, initiating the first battle between ironclad warships on March 9, 1862 at Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name for both a body of water and the Norfolk–Virginia Beach metropolitan area which surrounds it in southeastern Virginia, United States...

, Virginia

Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

. The battle ended in a tactical stalemate between the two ironclad warships, neither of which appeared capable of sinking the other, but strategically saved the remaining Union fleet from defeat. After this, numerous monitors were built for the Union, including twin turret versions, and contributed greatly to the naval victory of the Union over the rebellious states. Despite their low draft and subsequent problems in navigating in high seas, many basic design elements of the Monitor class were copied in future warships by other designers and navies. The rotating turret in particular is considered one of the greatest technological advances in naval history, still found on warships today.

Later Ericsson designed other naval vessels and weapons, including a type of torpedo

Torpedo

The modern torpedo is a self-propelled missile weapon with an explosive warhead, launched above or below the water surface, propelled underwater towards a target, and designed to detonate either on contact with it or in proximity to it.The term torpedo was originally employed for...

and a Destroyer, a torpedo boat

Torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval vessel designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs rammed enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes, and later designs launched self-propelled Whitehead torpedoes. They were created to counter battleships and other large, slow and...

that could fire a cannon from an underwater port. He also provided some technical support for John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland was an Irish engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the U.S...

in his early submarine experiments. In the book Contributions to the Centennial Exhibition (1877, reprinted 1976) he presented his "sun engines", which collected solar heat for a hot air engine

Hot air engine

A hot air engine is any heat engine which uses the expansion and contraction of air under the influence of a temperature change to convert thermal energy into mechanical work...

. One of these designs earned Ericsson additional income after being converted to work as a methane gas engine.

Although none of his inventions created any large industries, he is regarded as one of the most influential mechanical engineers ever. After his death in 1889 his remains were brought from the United States to Stockholm

Stockholm

Stockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area...

by USS Baltimore

USS Baltimore (C-3)

The fourth USS Baltimore was a United States Navy cruiser, the second protected cruiser to be built by an American yard. Like the previous one, , the design was commissioned from the British company of W...

; his final resting place is at Filipstad

Filipstad

Filipstad is a locality and the seat of Filipstad Municipality, Värmland County, Sweden with 6,177 inhabitants in 2005.Filipstad was granted city privileges in 1611 by Charles IX of Sweden, who named it after his son Duke Carl Philip .After a major fire destroyed forest and town in 1694, Filipstad...

, in Värmland

Värmland

' is a historical province or landskap in the west of middle Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Dalsland, Dalarna, Västmanland and Närke. It is also bounded by Norway in the west. Latin name versions are Vermelandia and Wermelandia. Although the province's land originally was Götaland, the...

.

Inventions

- The surface condenser

- The hot air engineHot air engineA hot air engine is any heat engine which uses the expansion and contraction of air under the influence of a temperature change to convert thermal energy into mechanical work...

- The worlds first monitor, USS MonitorUSS MonitorUSS Monitor was the first ironclad warship commissioned by the United States Navy during the American Civil War. She is most famous for her participation in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862, the first-ever battle fought between two ironclads...

, was both designed and built by Ericsson for the Union NavyUnion NavyThe Union Navy is the label applied to the United States Navy during the American Civil War, to contrast it from its direct opponent, the Confederate States Navy...

in the American Civil WarAmerican Civil WarThe American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25... - TorpedoTorpedoThe modern torpedo is a self-propelled missile weapon with an explosive warhead, launched above or below the water surface, propelled underwater towards a target, and designed to detonate either on contact with it or in proximity to it.The term torpedo was originally employed for...

technology, especially Destroyer, an advanced torpedo boatTorpedo boatA torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval vessel designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs rammed enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes, and later designs launched self-propelled Whitehead torpedoes. They were created to counter battleships and other large, slow and... - The solar machineSolar thermal collectorA solar thermal collector is a solar collector designed to collect heat by absorbing sunlight. The term is applied to solar hot water panels, but may also be used to denote more complex installations such as solar parabolic, solar trough and solar towers or simpler installations such as solar air...

, using concave mirrors to gather sun radiation strong enough to run an engine. - Hoop gunHoop gunA hoop gun is a gun production technique that uses multiple layers of tubes to form a built-up gun. The innermost tube has one or more extra tubes wrapped around the main tube. These outer tubes are preheated before they are slid into position. As the outer tubes cool they naturally contract. This...

construction - the PropellerPropellerA propeller is a type of fan that transmits power by converting rotational motion into thrust. A pressure difference is produced between the forward and rear surfaces of the airfoil-shaped blade, and a fluid is accelerated behind the blade. Propeller dynamics can be modeled by both Bernoulli's...

Fellowships

- Foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of SciencesRoyal Swedish Academy of SciencesThe Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

in 1850, Swedish member from 1863 - Royal Swedish Academy of War SciencesRoyal Swedish Academy of War SciencesThe Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences or Kungl. Krigsvetenskapsakademin, founded in 1739 by King Frederick I, is one of the Royal Academies in Sweden. The Academy is an independent organization and a forum for military and defense issues. Membership is limited to 160 chairs under the age of...

in 1852 - Honorary Doctorate at Lund UniversityLund UniversityLund University , located in the city of Lund in the province of Scania, Sweden, is one of northern Europe's most prestigious universities and one of Scandinavia's largest institutions for education and research, frequently ranked among the world's top 100 universities...

in 1868

Monuments and memorials

- John Ericsson National MemorialJohn Ericsson National MemorialJohn Ericsson National Memorial, located near the National Mall at Ohio Drive and Independence Avenue, SW,in Washington, D.C., is dedicated to the man who revolutionized naval history with his invention of the screw propeller...

on The Mall in Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution.... - The John Ericsson Room at the American Swedish Historical MuseumAmerican Swedish Historical MuseumThe American Swedish Historical Museum is the oldest Swedish-American museum in the United States. It is located in Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park in the South Philadelphia neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on part of a historic 17th-century land grant originally provided by Queen...

in ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles... - Battery ParkBattery ParkBattery Park is a 25-acre public park located at the Battery, the southern tip of Manhattan Island in New York City, facing New York Harbor. The Battery is named for artillery batteries that were positioned there in the city's early years in order to protect the settlement behind them...

, in New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and... - NybroplanNybroplanNybroplan is a public space in central Stockholm, Sweden. Located on the border between the city districts Norrmalm and Östermalm, Nybroplan connects a number of major streets, including Birger Jarlsgatan, Strandvägen, Hamngatan, and Nybrogatan...

in StockholmStockholmStockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area... - KungsportsavenynKungsportsavenynKungsportsavenyn, commonly known as just Avenyn , is the main street of Gothenburg, Sweden, and a smaller counterpart of the Champs-Élysées. It was created in the 1860s and 1870s as a result of an international town planning competition...

in GothenburgGothenburgGothenburg is the second-largest city in Sweden and the fifth-largest in the Nordic countries. Situated on the west coast of Sweden, the city proper has a population of 519,399, with 549,839 in the urban area and total of 937,015 inhabitants in the metropolitan area...

. - John Ericsson Street, in LundLund-Main sights:During the 12th and 13th centuries, when the town was the seat of the archbishop, many churches and monasteries were built. At its peak, Lund had 27 churches, but most of them were demolished as result of the Reformation in 1536. Several medieval buildings remain, including Lund...

, Sweden - John Ericsson fountain, Fairmount ParkFairmount ParkFairmount Park is the municipal park system of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It consists of 63 parks, with , all overseen by the Philadelphia Department of Parks and Recreation, successor to the Fairmount Park Commission in 2010.-Fairmount Park proper:...

, Philadelphia - Neighborhood of Ericsson, Minneapolis

For ships named in his honor, see:

- USS EricssonUSS EricssonUSS Ericsson has been the name of three warships in the United States Navy. They are all named for John Ericsson, the inventor of the USS Monitor and a torpedo that was cable-powered by an external source...

Organizations:

- The John Ericsson Republican League of Illinois is a Swedish-American partisan organization.

See also

- American Swedish Historical MuseumAmerican Swedish Historical MuseumThe American Swedish Historical Museum is the oldest Swedish-American museum in the United States. It is located in Franklin Delano Roosevelt Park in the South Philadelphia neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on part of a historic 17th-century land grant originally provided by Queen...

, John Ericsson Room - HMS Sölve - a Swedish monitor built 1875 and designed by Ericsson. It is currently in a Maritime Museum in GothenburgGothenburgGothenburg is the second-largest city in Sweden and the fifth-largest in the Nordic countries. Situated on the west coast of Sweden, the city proper has a population of 519,399, with 549,839 in the urban area and total of 937,015 inhabitants in the metropolitan area...

SwedenSwedenSweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

External links

- The Life of John Ericsson By William Conant Church, published 1911, 660 pages.

- John Ericsson National Memorial in Washington

- John Ericsson Society, New York – Centennial Anniversary year 2007

- John Ericsson at National Inventors Hall of Fame

- Monitor National Marine Sanctuary

- John Ericsson Statue in Gothenburg

- Some Pioneers in Air Engine Design – John Ericsson

- John Ericsson's solar engine

- 1870-02-19: CAPTAIN ERICSSON'S GUN CARRIAGE

- The Original United States Warship "Monitor" Correspondence between Cornelius Scranton BushnellCornelius Scranton BushnellCornelius Scranton Bushnell was an American railroad executive and shipbuilder who was instrumental in developing ironclad ships for the Union Navy during the American Civil War.-Background:...

, John Ericsson, Gideon Wells, published 1899, 52 pages, compiled by William S. Wells.