John Coolidge Adams

Encyclopedia

Pulitzer Prize for Music

The Pulitzer Prize for Music was first awarded in 1943. Joseph Pulitzer did not call for such a prize in his will, but had arranged for a music scholarship to be awarded each year...

-winning American composer with strong roots in minimalism

Minimalist music

Minimal music is a style of music associated with the work of American composers La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. It originated in the New York Downtown scene of the 1960s and was initially viewed as a form of experimental music called the New York Hypnotic School....

. His best-known works include Short Ride in a Fast Machine

Short Ride in a Fast Machine

Short Ride in a Fast Machine is a musical piece composed by John Adams. The piece has now become one of the most frequently requested and performed encores in American concert-halls...

(1986), On the Transmigration of Souls

On the Transmigration of Souls

On the Transmigration of Souls, for orchestra, chorus, children’s choir and pre-recorded tape is a composition by composer John Adams commissioned by The New York Philharmonic and Lincoln Center’s Great Performers shortly after the September 11 terrorist attacks.Adams began writing the piece in...

(2002), a choral piece commemorating the victims of the September 11, 2001 attacks

September 11, 2001 attacks

The September 11 attacks The September 11 attacks The September 11 attacks (also referred to as September 11, September 11th or 9/119/11 is pronounced "nine eleven". The slash is not part of the pronunciation...

(for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for Music

Pulitzer Prize for Music

The Pulitzer Prize for Music was first awarded in 1943. Joseph Pulitzer did not call for such a prize in his will, but had arranged for a music scholarship to be awarded each year...

in 2003), and Shaker Loops

Shaker Loops

Written in 1978 by the American composer John Adams, Shaker Loops was originally written for string septet. A version for string orchestra followed in 1983 and first performed in April of that year at Alice Tully Hall New York, by the American Composers Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson...

(1978), a minimalist four-movement work for strings. His well-known operas include Nixon in China

Nixon in China (opera)

Nixon in China is an opera in three acts by John Adams, with a libretto by Alice Goodman. Adams' first opera, it was inspired by the 1972 visit to China by US President Richard Nixon. The work premiered at the Houston Grand Opera on October 22, 1987, in a production by Peter Sellars with...

(1987), which recounts Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

's 1972 visit to China, and Doctor Atomic

Doctor Atomic

Doctor Atomic is an opera by the contemporary American composer John Adams, with libretto by Peter Sellars. It premiered at the San Francisco Opera on 1 October 2005. The work focuses on the great stress and anxiety experienced by those at Los Alamos while the test of the first atomic bomb was...

(2005), which covers Robert Oppenheimer

Robert Oppenheimer

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan Project, the World War II project that developed the first...

, the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

, and the building of the first atomic bomb.

Before 1977

John Coolidge Adams was born in Worcester, MassachusettsWorcester, Massachusetts

Worcester is a city and the county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, as of the 2010 Census the city's population is 181,045, making it the second largest city in New England after Boston....

in 1947. He was raised in various New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

states where he was greatly influenced by New England's musical culture. He graduated from Concord High School

Concord High School (New Hampshire)

Concord High School is a high school in Concord, New Hampshire in the United States.- History :Concord's first public high school was established in 1846. The original building was the building on the corner of State and School Streets. A new school house was built in 1862, which stood until April...

in Concord, New Hampshire

Concord, New Hampshire

The city of Concord is the capital of the state of New Hampshire in the United States. It is also the county seat of Merrimack County. As of the 2010 census, its population was 42,695....

. His father taught him how to play the clarinet, and he was a clarinetist in community ensembles. He later studied the instrument further with Felix Viscuglia, clarinetist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra is an orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is one of the five American orchestras commonly referred to as the "Big Five". Founded in 1881, the BSO plays most of its concerts at Boston's Symphony Hall and in the summer performs at the Tanglewood Music Center...

.

Adams began composing at the age of ten and first heard his music performed around the age of 13 or 14. After he matriculated at Harvard University

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

in 1965 he studied composition under Leon Kirchner

Leon Kirchner

Leon Kirchner was an American composer of contemporary classical music. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his String Quartet No. 3.Kirchner was born in Brooklyn, New York...

, Roger Sessions

Roger Sessions

Roger Huntington Sessions was an American composer, critic, and teacher of music.-Life:Sessions was born in Brooklyn, New York, to a family that could trace its roots back to the American revolution. His mother, Ruth Huntington Sessions, was a direct descendent of Samuel Huntington, a signer of...

, Earl Kim

Earl Kim

Earl Kim was a Korean-American composer.Kim was born in Dinuba, California, to immigrant Korean parents. He began piano studies at age ten and soon developed an interest in composition, studying in Los Angeles and Berkeley with, among others, Arnold Schoenberg, Ernest Bloch, and Roger Sessions...

, and David Del Tredici

David Del Tredici

David Del Tredici, born March 16, 1937 in Cloverdale, California, is an American composer. According to Del Tredici's website, Aaron Copland said David Del Tredici "is that rare find among composers — a creator with a truly original gift...

. While at Harvard, he conducted the Bach Society Orchestra and was a reserve clarinetist for both the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra is an orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is one of the five American orchestras commonly referred to as the "Big Five". Founded in 1881, the BSO plays most of its concerts at Boston's Symphony Hall and in the summer performs at the Tanglewood Music Center...

and the Opera Company of Boston

Opera Company of Boston

The Opera Company of Boston was an American opera company located in Boston, Massachusetts that was active during the late 1950s through the early 1990s. The company was founded by American conductor Sarah Caldwell in 1958 under the name Boston Opera Group. At one time, the touring arm of the...

. He earned two degrees from Harvard University (BA 1971, MA 1972) and was among the first students to be allowed to submit a musical composition for a Harvard undergraduate thesis. His piece "American Standard

American Standard (John Adams)

American Standard is an early ensemble work by noted American composer John Adams. It consists of three movements: a march, a hymn, and a jazz standard...

" was recorded and released on Obscure Records

Obscure Records

Obscure Records was a U.K. record label which existed from 1975 to 1978. It was created and run by Brian Eno, who also produced the albums . Ten albums were issued in the series...

in 1975. He taught at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music

San Francisco Conservatory of Music

San Francisco Conservatory of Music, formerly the California Conservatory of Music, founded in 1917, is a music school, with an enrollment of about 400 students. It was launched by Ada Clement and Lillian Hodgehead in the remodeled home of Lillian's parents on Sacramento Street. It was called the...

from 1972 until 1984.

1977 to Nixon in China

Adams worked in the electronic music studio at the San Francisco Conservatory of MusicSan Francisco Conservatory of Music

San Francisco Conservatory of Music, formerly the California Conservatory of Music, founded in 1917, is a music school, with an enrollment of about 400 students. It was launched by Ada Clement and Lillian Hodgehead in the remodeled home of Lillian's parents on Sacramento Street. It was called the...

, having built his own analogue synthesizer, and as conductor of the New Music Ensemble, he had a small but dedicated pool of young and talented musicians occasionally at his disposal.

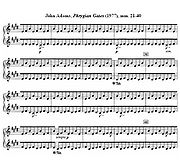

Some major works composed during this period include Wavemaker (1977), Phrygian Gates for solo piano (1977), Shaker Loops (1978), Common Tones in Simple Time (1979), Harmonium (1980–81), Grand Pianola Music (1982), Light Over Water (1983), Harmonielehre (1984–85), The Chairman Dances (1985), Short Ride in a Fast Machine (1986), and Nixon in China (1985–87).

Shaker Loops

Shaker Loops

Written in 1978 by the American composer John Adams, Shaker Loops was originally written for string septet. A version for string orchestra followed in 1983 and first performed in April of that year at Alice Tully Hall New York, by the American Composers Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson...

(for string septet) (1978): A "modular" composition for three violins, one viola, two cellos, and one bass, with a conductor. It is divided into four distinct movements, each of which grows almost indiscernibly into the next. Adams worked with a group of Conservatory string players, at times composing as they rehearsed. The "period" – that is, the number of beats per repeated pattern – of each instrument is different, and this results in a constantly shifting texture of melody and rhythmic emphasis. This piece is a turning point in Adams's oeuvre, as it marks a return to pure instrumental writing and a re-engagement with tonality. Adams later arranged this piece for string orchestra.

Harmonium

Harmonium (John Adams)

Harmonium is a composition for chorus and orchestra that could be considered a choral symphony in all but name, by the American composer John Adams, written in 1980-1981 for the first season of Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco, California. The work is based on poetry by John Donne and Emily...

for Large Orchestra and Chorus (1980–81): The piece starts with quietly insistent repetitions of one note – D – and one syllable – "no". The successful Harmonium premiere was the first performance of his music by a major mainstream organization, and established Adams as a figure in America's musical landscape.

Grand Pianola Music

Grand Pianola Music

Grand Pianola Music is a minimalist composition by American composer John Adams. It was written in 1982 and premiered at New York's Avery Fisher Hall.The work is in three movements:*Part 1A *Part 1B *'On The Dominant Divide'...

(1982): Adams commented, "Dueling pianos, cooing sirens, Valhalla brass, thwacking bass drums, gospel triads, and a Niagara of cascading flat keys all learned to cohabit as I wrote the piece." It is one of his first major works to incorporate American vernacular music within a classical symphonic tradition. Adams's use of the repetitive patterns of minimalism

Minimalism

Minimalism describes movements in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, where the work is set out to expose the essence, essentials or identity of a subject through eliminating all non-essential forms, features or concepts...

within sweeping orchestral gestures is heard throughout the piece.

Light Over Water: The Genesis of Music (1983): This work was commissioned by the Museum of Contemporary Art

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles is a contemporary art museum with three locations in greater Los Angeles, California. The main branch is located on Grand Avenue in Downtown Los Angeles, near Walt Disney Concert Hall...

in Los Angeles as the score for the collaborative work Available Light, which was choreographed by Lucinda Childs

Lucinda Childs

Lucinda Childs is an American postmodern dancer/choreographer. Her compositions are known for their minimalistic movements yet complex transitions. Childs is most famous for being able to turn the slightest movements into an intricate choreographic masterpiece...

and had a set design by architect Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry

Frank Owen Gehry, is a Canadian American Pritzker Prize-winning architect based in Los Angeles, California.His buildings, including his private residence, have become tourist attractions...

. The work is a long, unbroken composition with contrasting sections whose boundaries are so subtle as to be almost imperceptible. It is a kind of symphony played by an orchestra of both electric and natural instruments and frozen into its idealized form by means of a multichannel tape recorder. Essentially electronic, the piece still exhibits orchestral techniques. Changes in the piece evolve gradually, and sudden entrances are rare. It is personal and emotive, though not necessarily romantic, and it has a dance-like feel.

Harmonielehre

Harmonielehre (John Adams)

Harmonielehre is a 1985 composition by American composer John Adams. The composition's title, German for "study of harmony," also the title of a book by Arnold Schoenberg, hints at the work's combination of Schoenberg's harmonic principles with those of minimalism.Adams has stated that the piece...

(1984–85): Inspired by a dream of an oil tanker taking flight out of San Francisco Bay and also by Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg was an Austrian composer, associated with the expressionist movement in German poetry and art, and leader of the Second Viennese School...

's book, Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony). This piece is also about harmony of the mind and was Adams's way of escaping writer's block.

The Chairman Dances (Foxtrot for Orchestra)

The Chairman Dances

The Chairman Dances is a 1985 composition by John Adams. Subtitled Foxtrot for Orchestra, the piece lasts about 13 minutes. The piece was composed on commission from the Milwaukee Symphony, and is described by Adams as an "out take" from Act III of the opera he was working on at the time, Nixon in...

(1985): This is a by-product of Nixon in China, set in the three days of President Nixon's visit to Beijing in February 1972.

Short Ride in a Fast Machine (Fanfare for Great Woods)

Short Ride in a Fast Machine

Short Ride in a Fast Machine is a musical piece composed by John Adams. The piece has now become one of the most frequently requested and performed encores in American concert-halls...

(1986): This piece is joyfully exuberant, brilliantly scored for a large orchestra. It begins with a marking of half-notes (woodblock, soon joined by the four trumpets) and eighths (clarinets and synthesizers); the (amplified) woodblock is fortissimo and the other instruments play forte. The work uses many elements of minimalist music.

Nixon in China

Nixon in China (opera)

Nixon in China is an opera in three acts by John Adams, with a libretto by Alice Goodman. Adams' first opera, it was inspired by the 1972 visit to China by US President Richard Nixon. The work premiered at the Houston Grand Opera on October 22, 1987, in a production by Peter Sellars with...

(1987): The opera, in three acts, is based on Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

's visit to China on February 21–25, 1972. Main characters in the opera are: the Nixons, Mao Tse-tung, Chou En-lai, Chiang Ch'ing (Madame Mao) and Henry Kissinger

Henry Kissinger

Heinz Alfred "Henry" Kissinger is a German-born American academic, political scientist, diplomat, and businessman. He is a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He served as National Security Advisor and later concurrently as Secretary of State in the administrations of Presidents Richard Nixon and...

. Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

's visit to Beijing was made in the hope, but by no means the certainty, that he would see chairman Mao. It was directed by Peter Sellars

Peter Sellars

Peter Sellars is an American theatre director, noted for his unique contemporary stagings of classical and contemporary operas and plays...

. This piece is John Adams's second major composition on a text, after Harmonium (1981) for chorus and orchestra.

After Nixon in China

Adams wrote, "in almost all cultures other than the European classical one, the real meaning of the music is in between the notes. The slide, the portamentoPortamento

Portamento is a musical term originated from the Italian expression "portamento della voce" , denoting from the beginning of the 17th century a vocal slide between two pitches and its emulation by members of the violin family and certain wind instruments, and is sometimes used...

, the "blue note

Blue note

In jazz and blues, a blue note is a note sung or played at a slightly lower pitch than that of the major scale for expressive purposes. Typically the alteration is a semitone or less, but this varies among performers and genres. Country blues, in particular, features wide variations from the...

"—all are essential to the emotional expression, whether it's a great Indian master improvising on a raga or whether it's Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix was an American guitarist and singer-songwriter...

or Johnny Hodges

Johnny Hodges

John Cornelius "Johnny" Hodges was an American alto saxophonist, best known for his solo work with Duke Ellington's big band. He played lead alto in the saxophone section for many years, except the period between 1932–1946 when Otto Hardwick generally played first chair...

bending a blue note right down to the floor." Adams uses this concept in many of his influential pieces post-Nixon in China.

In October 2008, Adams told BBC Radio 3 that he had been blacklisted by the U.S. Homeland Security department and immigration services.

The Wound-Dresser

The Wound-Dresser

The Wound-Dresser is a nineteen minute-long piece by U.S. composer John Adams for orchestra and baritone singer. The piece is an elegiac setting of excerpts from American poet Walt Whitman's The Wound-Dresser about his experience as a nurse during the American Civil War. It was written in 1989...

(1988): John Adams's setting of Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman

Walter "Walt" Whitman was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among the most influential poets in the American canon, often called the father of free verse...

's poem, "The Wound-Dresser", which Whitman wrote after visiting wounded soldiers during the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. The piece is scored for baritone voice, 2 flutes (or 2 piccolos), 2 oboes, clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet (or piccolo tpt), timpani, synthesizer, and strings.

The Death of Klinghoffer

The Death of Klinghoffer

The Death of Klinghoffer is an American opera, with music by John Adams to an English-language libretto by Alice Goodman. First produced in Brussels and New York in 1991, the opera is based on the hijacking of the passenger liner Achille Lauro by the Palestine Liberation Front in 1985, and the...

(1991): The opera's story begins with the 1985 hijacking of the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro

MS Achille Lauro

MS Achille Lauro was a cruise ship based in Naples, Italy. Built between 1939 and 1947 as MS Willem Ruys, a passenger liner for the Rotterdamsche Lloyd. It is most remembered for its 1985 hijacking...

by Palestinian

Palestinian people

The Palestinian people, also referred to as Palestinians or Palestinian Arabs , are an Arabic-speaking people with origins in Palestine. Despite various wars and exoduses, roughly one third of the world's Palestinian population continues to reside in the area encompassing the West Bank, the Gaza...

terrorists and details the murder of a passenger named Leon Klinghoffer

Leon Klinghoffer

Leon Klinghoffer was a disabled American appliance manufacturer who was murdered and thrown overboard by Palestinian terrorists in the hijacking of the cruise ship Achille Lauro in 1985.-Hijacking and murder:...

, a retired, physically disabled American Jew. The musical basis for The Death of Klinghoffer was the Passions of Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach was a German composer, organist, harpsichordist, violist, and violinist whose sacred and secular works for choir, orchestra, and solo instruments drew together the strands of the Baroque period and brought it to its ultimate maturity...

: grave, symbolic, narratives supported by a full chorus. A film version was made in 2003, which emphasised the work's somber, chilling mood.

Chamber Symphony (1992): This piece was commissioned by the Gerbode Foundation of San Francisco for the San Francisco Contemporary Chamber Players. While Chamber Symphony bears a strong resemblance to Arnold Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony Op. 9 in its tonality and its instrumental arrangement, Adams's additional instrumentation includes synthesizer, drum kit, trumpet, and trombone. The piece consists of three movements: "Mongrel Airs," "Aria with Walking Bass" and "Roadrunner." The piece is excited and aggressive, alluding to children's cartoon music (as evidenced by the titles of the movements). The piece is linear, chromatic, and virtuosic.

I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky

I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky

I Was Looking at the Ceiling and Then I Saw the Sky is a 1995 musical/opera with music composed by John Adams, with a libretto by June Jordan. The work was first performed May 1995 in Berkeley, California with staging by Peter Sellars...

(1995): A stage piece with libretto

Libretto

A libretto is the text used in an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata, or musical. The term "libretto" is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major liturgical works, such as mass, requiem, and sacred cantata, or even the story line of a...

by June Jordan

June Jordan

June Millicent Jordan was a Caribbean American poet, novelist, journalist, biographer, dramatist, teacher and committed activist...

and staging by Peter Sellars

Peter Sellars

Peter Sellars is an American theatre director, noted for his unique contemporary stagings of classical and contemporary operas and plays...

. Adams called the piece "essentially a polyphonic love story in the style of a Shakespeare comedy." The main characters are seven young Americans from different social and ethnic backgrounds, all living in Los Angeles. The story takes place in the aftermath of the earthquake in Los Angeles in 1994.

Hallelujah Junction

Hallelujah Junction

Hallelujah Junction is a piece written in 1996 for two pianos by the American composer John Adams.-Composition:The name comes from a small truck stop on US 395 which meets Alternate US 40, near the California–Nevada border. Adams said of the piece, "Here we have a case of a great title looking for...

(1996): This piece for two pianos employs variations of a repeated two note rhythm. The interval

Interval (music)

In music theory, an interval is a combination of two notes, or the ratio between their frequencies. Two-note combinations are also called dyads...

s between the notes remain the same through much of the piece.

On the Transmigration of Souls

On the Transmigration of Souls

On the Transmigration of Souls, for orchestra, chorus, children’s choir and pre-recorded tape is a composition by composer John Adams commissioned by The New York Philharmonic and Lincoln Center’s Great Performers shortly after the September 11 terrorist attacks.Adams began writing the piece in...

(2002): This piece commemorates those who lost their lives in the September 11, 2001 attacks

September 11, 2001 attacks

The September 11 attacks The September 11 attacks The September 11 attacks (also referred to as September 11, September 11th or 9/119/11 is pronounced "nine eleven". The slash is not part of the pronunciation...

on the World Trade Center in New York. It won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Music

Pulitzer Prize for Music

The Pulitzer Prize for Music was first awarded in 1943. Joseph Pulitzer did not call for such a prize in his will, but had arranged for a music scholarship to be awarded each year...

as well as the 2005 Grammy Award

Grammy Award

A Grammy Award — or Grammy — is an accolade by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences of the United States to recognize outstanding achievement in the music industry...

for Best Contemporary Composition. Adams was the first composer to have earned the latter award three times, having previously won the award for El Dorado (1998) and Nixon in China

Nixon in China

Nixon in China may refer to:*1972 Nixon visit to China, U.S. President Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to the People's Republic of China**"Nixon in China" , a reference to the above used as a metaphor for an unexpected or uncharacteristic action by a politician*Nixon in China, an opera by composer John...

(1989).

My Father Knew Charles Ives (2003): Adams writes, "My Father Knew Charles Ives is musical autobiography, an homage and encomium to a composer whose influence on me has been huge." In true Ives style, in all three movements the piece begins subtly with few instruments and swells to a cacophonous mass of sound. The piece ranges from utilizing mysterious harmonies in long tones to full scale march feels.

The Dharma at Big Sur

The Dharma at Big Sur

The Dharma at Big Sur is a composition for solo electric violin and orchestra by John Adams. The piece calls for some instruments to use just intonation, a tuning system in which intervals sound pure, rather than equal temperament, the common Western tuning system in which all intervals except the...

(2003): A piece for solo electric six-string violin and orchestra. The piece calls for some instruments (harp, piano, samplers) to use just intonation

Just intonation

In music, just intonation is any musical tuning in which the frequencies of notes are related by ratios of small whole numbers. Any interval tuned in this way is called a just interval. The two notes in any just interval are members of the same harmonic series...

, a tuning system in which intervals sound pure, rather than equal temperament

Equal temperament

An equal temperament is a musical temperament, or a system of tuning, in which every pair of adjacent notes has an identical frequency ratio. As pitch is perceived roughly as the logarithm of frequency, this means that the perceived "distance" from every note to its nearest neighbor is the same for...

, the common Western tuning system in which all intervals except the octave are impure. The piece was composed for the opening of Disney Hall in Los Angeles.

Doctor Atomic

Doctor Atomic

Doctor Atomic is an opera by the contemporary American composer John Adams, with libretto by Peter Sellars. It premiered at the San Francisco Opera on 1 October 2005. The work focuses on the great stress and anxiety experienced by those at Los Alamos while the test of the first atomic bomb was...

(2005): An opera in two acts, about Robert Oppenheimer

Robert Oppenheimer

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan Project, the World War II project that developed the first...

, the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

, and the creation and testing of the first atomic bomb. The libretto of Doctor Atomic by Peter Sellars

Peter Sellars

Peter Sellars is an American theatre director, noted for his unique contemporary stagings of classical and contemporary operas and plays...

draws on original source material, including personal memoirs, recorded interviews, technical manuals of nuclear physics, declassified government documents, and the poetry of the Bhagavad Gita

Bhagavad Gita

The ' , also more simply known as Gita, is a 700-verse Hindu scripture that is part of the ancient Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata, but is frequently treated as a freestanding text, and in particular, as an Upanishad in its own right, one of the several books that constitute general Vedic tradition...

, John Donne

John Donne

John Donne 31 March 1631), English poet, satirist, lawyer, and priest, is now considered the preeminent representative of the metaphysical poets. His works are notable for their strong and sensual style and include sonnets, love poetry, religious poems, Latin translations, epigrams, elegies, songs,...

, Charles Baudelaire

Charles Baudelaire

Charles Baudelaire was a French poet who produced notable work as an essayist, art critic, and pioneering translator of Edgar Allan Poe. His most famous work, Les Fleurs du mal expresses the changing nature of beauty in modern, industrializing Paris during the nineteenth century...

, and Muriel Rukeyser

Muriel Rukeyser

Muriel Rukeyser was an American poet and political activist, best known for her poems about equality, feminism, social justice, and Judaism...

. The opera takes place in June and July 1945, mainly over the last few hours before the first atomic bomb explodes at the test site in New Mexico. Characters include Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer

Robert Oppenheimer

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan Project, the World War II project that developed the first...

and his wife Kitty, Edward Teller

Edward Teller

Edward Teller was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist, known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb," even though he did not care for the title. Teller made numerous contributions to nuclear and molecular physics, spectroscopy , and surface physics...

, General Leslie Groves

Leslie Groves

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves, Jr. was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb during World War II. As the son of a United States Army chaplain, Groves lived at a...

, and Robert Wilson

Robert R. Wilson

Robert Rathbun Wilson was an American physicist who was a group leader of the Manhattan Project, a sculptor, and an architect of Fermi National Laboratory , where he was also the director from 1967–1978....

.

A Flowering Tree (2006): An opera in two acts, based on a folktale from the Kannada language of southern India as translated by A.K. Ramanujan. it was commissioned as part of the Vienna New Crowned Hope Festival to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birth. It takes as its model Mozart’s The Magic Flute, and its themes are magic, transformation and the dawning of moral awareness.

Doctor Atomic Symphony (2007): Based on music from the opera.

Fellow Traveler (2007): This piece was commissioned for the Kronos Quartet

Kronos Quartet

Kronos Quartet is a string quartet founded by violinist David Harrington in 1973 in Seattle, Washington. Since 1978, the quartet has been based in San Francisco, California. The longest-running combination of performers had Harrington and John Sherba on violin, Hank Dutt on viola, and Joan...

by Greg G. Minshall, and was dedicated to opera and theater director Peter Sellars for his 50th birthday.

Musical style

The music of John Adams is usually categorized as minimalist or post-minimalist although in interview he has categorised himself in typically witty fashion as a 'post-style' composer. While Adams employs minimalist techniques, such as repeating patterns, he is not a strict follower of the movement. Adams was born a generation after Steve ReichSteve Reich

Stephen Michael "Steve" Reich is an American composer who together with La Monte Young, Terry Riley, and Philip Glass is a pioneering composer of minimal music...

and Philip Glass

Philip Glass

Philip Glass is an American composer. He is considered to be one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century and is widely acknowledged as a composer who has brought art music to the public .His music is often described as minimalist, along with...

, and his writing is more developmental and directionalized, containing climaxes and other elements of Romanticism

Romanticism

Romanticism was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution...

. Comparing Shaker Loops to minimalist composer Terry Riley

Terry Riley

Terrence Mitchell Riley, is an American composer intrinsically associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music and was a pioneer of the movement...

's piece In C

In C

In C is a semi-aleatoric musical piece composed by Terry Riley in 1964 for any number of people, although he suggests "a group of about 35 is desired if possible but smaller or larger groups will work"...

, Adams says,

rather than set up small engines of motivic materials and let them run free in a kind of random play of counterpoint, I used the fabric of continually repeating cells to forge large architectonic shapes, creating a web of activity that, even within the course of a single movement, was more detailed, more varied, and knew both light and dark, serenity and turbulence.

Many of Adams's ideas in composition are a reaction to the philosophy of serialism

Serialism

In music, serialism is a method or technique of composition that uses a series of values to manipulate different musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, though his contemporaries were also working to establish serialism as one example of...

and its depictions of "the composer as scientist." The Darmstadt school

Darmstadt School

Darmstadt School refers to a loose group of compositional styles created by composers who attended the Darmstadt International Summer Courses for New Music from the early 1950s to the early 1960s.-History:...

of twelve tone composition was dominant during the time that Adams was receiving his college education, and he compared class to a "mausoleum where we would sit and count tone-rows in Webern

Anton Webern

Anton Webern was an Austrian composer and conductor. He was a member of the Second Viennese School. As a student and significant follower of Arnold Schoenberg, he became one of the best-known exponents of the twelve-tone technique; in addition, his innovations regarding schematic organization of...

." By the time he graduated, he was disillusioned with the restrained feeling and inaccessibility of serialism.

Adams experienced a musical awakening after reading John Cage

John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. was an American composer, music theorist, writer, philosopher and artist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde...

's book Silence (1973), which he claimed "dropped into [his] psyche like a time bomb." Cage's school posed fundamental questions about what music was, and regarded all types of sounds as viable sources of music. This perspective offered to Adams a liberating alternative to the rule-based techniques of serialism. At this point Adams began to experiment with electronic music

Electronic music

Electronic music is music that employs electronic musical instruments and electronic music technology in its production. In general a distinction can be made between sound produced using electromechanical means and that produced using electronic technology. Examples of electromechanical sound...

, and his experiences are reflected in the writing of Phrygian Gates (1977–78), in which the constant shifting between modules in Lydian mode

Lydian mode

The Lydian musical scale is a rising pattern of pitches comprising three whole tones, a semitone, two more whole tones, and a final semitone. This sequence of pitches roughly describes the fifth of the eight Gregorian modes, known as Mode V or the authentic mode on F, theoretically using B but in...

and Phrygian mode

Phrygian mode

The Phrygian mode can refer to three different musical modes: the ancient Greek tonos or harmonia sometimes called Phrygian, formed on a particular set octave species or scales; the Medieval Phrygian mode, and the modern conception of the Phrygian mode as a diatonic scale, based on the latter...

refers to activating electronic gates rather than architectural ones. Adams explained that working with synthesizers caused a "diatonic conversion," a reversion to the belief that tonality

Tonality

Tonality is a system of music in which specific hierarchical pitch relationships are based on a key "center", or tonic. The term tonalité originated with Alexandre-Étienne Choron and was borrowed by François-Joseph Fétis in 1840...

was a force of nature.

Minimalism offered the final solution to Adams's creative dilemma. Adams was attracted to its pulsating and diatonic sound, which provided an underlying rhetoric on top of which Adams could express what he wanted in his compositions. Although some of his pieces sound similar to those written by minimalist composers, Adams actually rejects the idea of mechanistic procedure-based or process music

Process music

Process music is music that arises from a process. It may make that process audible to the listener, or the process may be concealed. Primarily begun in the 1960s, diverse composers have employed divergent methods and styles of process...

; what Adams took away from minimalism was tonality and/or modality, and the rhythmic energy from repetition.

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler was a late-Romantic Austrian composer and one of the leading conductors of his generation. He was born in the village of Kalischt, Bohemia, in what was then Austria-Hungary, now Kaliště in the Czech Republic...

, J. S. Bach, and Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was a German composer and pianist, and one of the leading musicians of the Romantic period. Born in Hamburg, Brahms spent much of his professional life in Vienna, Austria, where he was a leader of the musical scene...

, who "were standing at the end of an era and were embracing all of the evolutions that occurred over the previous thirty to fifty years."

Style and analysis

Philip Glass

Philip Glass is an American composer. He is considered to be one of the most influential composers of the late 20th century and is widely acknowledged as a composer who has brought art music to the public .His music is often described as minimalist, along with...

), used a steady pulse that defines and controls the music. The pulse was best known from Terry Riley

Terry Riley

Terrence Mitchell Riley, is an American composer intrinsically associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music and was a pioneer of the movement...

's early composition In C

In C

In C is a semi-aleatoric musical piece composed by Terry Riley in 1964 for any number of people, although he suggests "a group of about 35 is desired if possible but smaller or larger groups will work"...

, and slowly more and more composers used it as a common practice. Jonathan Bernard highlighted this adoption by comparing Phrygian Gates

Phrygian Gates

Phrygian Gates is a piano piece written by minimalist composer John Coolidge Adams in 1977-1978.The piece, together with its smaller companion China Gates is what is considered Adams' "opus one". They are, according to his own claims, his first compositions consisting of a coherent personal style...

, written in 1977, and Fearful Symmetries written eleven years later in 1988.

Violin Concerto, Mvt. III "Toccare"

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Adams started to add a new character to his music, something he called "the Trickster." The Trickster allowed Adams to use the repetitive style and rhythmic drive of minimalism, yet poke fun at it at the same time. When Adams commented on his own characterization of particular minimalist music, he stated that he went joyriding on "those Great Prairies of non-event."

Ostinato

In music, an ostinato is a motif or phrase, which is persistently repeated in the same musical voice. An ostinato is always a succession of equal sounds, wherein each note always has the same weight or stress. The repeating idea may be a rhythmic pattern, part of a tune, or a complete melody in...

." The third movement of the Violin Concerto, titled "Toccare" portrays this transition.

Adams begins the movement with a repeated, scale-like eight-note melody in the violin and going into the second measure, it appears as if he will continue this, but instead of starting at the bottom again, the violin continues upward. From here, there are fewer instances of repletion and more moving up and down in a pulse like fashion. The orchestra on the other hand is more repetitive and pulse like: the left hand continually plays the high A and it is not until the 5th measure where another note is added, but the A continues to be played throughout always on the off beat. It is this pulsing A, played as an eighth note as opposed to a sixteenth note, that pokes fun at the minimalist, yet Adams still uses the pulse (i.e. alternating eighth notes between the right and left hand, creating a sixteenth note feeling) as an engine for the movement.

Critical reception

John Adams was awarded the Pulitzer PrizePulitzer Prize for Music

The Pulitzer Prize for Music was first awarded in 1943. Joseph Pulitzer did not call for such a prize in his will, but had arranged for a music scholarship to be awarded each year...

in 2003 for his 9/11 memorial piece, On the Transmigration of Souls

On the Transmigration of Souls

On the Transmigration of Souls, for orchestra, chorus, children’s choir and pre-recorded tape is a composition by composer John Adams commissioned by The New York Philharmonic and Lincoln Center’s Great Performers shortly after the September 11 terrorist attacks.Adams began writing the piece in...

. Response to his output as a whole has been more divided, and Adams's works have been described as both brilliant and boring in reviews that stretch across both ends of the rating spectrum. Shaker Loops

Shaker Loops

Written in 1978 by the American composer John Adams, Shaker Loops was originally written for string septet. A version for string orchestra followed in 1983 and first performed in April of that year at Alice Tully Hall New York, by the American Composers Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson...

has been described as "hauntingly ethereal," while 1999's "Naïve and Sentimental Music" has been called "an exploration of a marvelously extended spinning melody." The New York Times called 1996's Hallelujah Junction

Hallelujah Junction

Hallelujah Junction is a piece written in 1996 for two pianos by the American composer John Adams.-Composition:The name comes from a small truck stop on US 395 which meets Alternate US 40, near the California–Nevada border. Adams said of the piece, "Here we have a case of a great title looking for...

"a two-piano work played with appealingly sharp edges," and 2001's "American Berserk" "a short, volatile solo piano work."

The most critically divisive pieces in Adams's collection are his historical operas. While it is now easy to say that Nixon in China

Nixon in China

Nixon in China may refer to:*1972 Nixon visit to China, U.S. President Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to the People's Republic of China**"Nixon in China" , a reference to the above used as a metaphor for an unexpected or uncharacteristic action by a politician*Nixon in China, an opera by composer John...

s influential score spawned a new interest in opera, it was not always met with such laudatory and generous review. At first release, Nixon in China received mostly mixed if not negative press feedback. Donal Henahan, special to the New York Times, called the Houston Grand Opera

Houston Grand Opera

Houston Grand Opera Houston Grand Opera was founded in 1955 through the joint efforts of Maestro Walter Herbert and cultural leaders Mrs. Louis G. Lobit, Edward Bing and Charles Cockrell...

world premiere of the work "worth a few giggles but hardly a strong candidate for the standard repertory" and "visually striking but coy and insubstantial." James Wierzbicki for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch is the major city-wide newspaper in St. Louis, Missouri. Although written to serve Greater St. Louis, the Post-Dispatch is one of the largest newspapers in the Midwestern United States, and is available and read as far west as Kansas City, Missouri, as far south as...

described Adams's score as the weak point in an otherwise well-staged performance, noting the music as "inappropriately placid," "cliché-ridden in the abstract" and "[trafficked] heavily in Adams's worn-out Minimalist clichés." With time, however, the opera has come to be revered as a great and influential production. Robert Hugill for Music and Vision called the production "astonishing … nearly twenty years after its premier," while City Beats Tom McElfresh called Nixon's score "a character in the drama" and "too intricate, too detailed to qualify as minimalist."

The attention surrounding The Death of Klinghoffer

The Death of Klinghoffer

The Death of Klinghoffer is an American opera, with music by John Adams to an English-language libretto by Alice Goodman. First produced in Brussels and New York in 1991, the opera is based on the hijacking of the passenger liner Achille Lauro by the Palestine Liberation Front in 1985, and the...

has been full of controversy, specifically in the New York Times reviews. After the 1991 premiere, reporter Edward Rothstein wrote that "Mr. Adams's music has a seriously limited range." Only a few days later, Allan Kozinn wrote an investigative report citing that Leon Klinghoffer

Leon Klinghoffer

Leon Klinghoffer was a disabled American appliance manufacturer who was murdered and thrown overboard by Palestinian terrorists in the hijacking of the cruise ship Achille Lauro in 1985.-Hijacking and murder:...

's daughters, Lisa and Ilsa, had "expressed their disapproval" of the opera in a statement saying "We are outraged at the exploitation of our parents and the coldblooded murder of our father as the centerpiece of a production that appears to us to be anti-Semitic." In response to these accusations of anti-Semitism, composer and Oberlin College

Oberlin College

Oberlin College is a private liberal arts college in Oberlin, Ohio, noteworthy for having been the first American institution of higher learning to regularly admit female and black students. Connected to the college is the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, the oldest continuously operating...

professor Conrad Cummings wrote a letter to the editor defending "Klinghoffer" as "the closest analogue to the experience of Bach's audience attending his most demanding works," and noted that, as someone of half-Jewish heritage, he "found nothing anti-Semitic about the work." After the 2001 cancellation of performances of excerpts from "Klinghoffer" by the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra is an orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is one of the five American orchestras commonly referred to as the "Big Five". Founded in 1881, the BSO plays most of its concerts at Boston's Symphony Hall and in the summer performs at the Tanglewood Music Center...

, debate has continued about the opera's content and social worth. Prominent critic and noted musicologist Richard Taruskin

Richard Taruskin

Richard Taruskin is an American-Russian musicologist, music historian, and critic who has written about the theory of performance, Russian music, fifteenth-century music, twentieth-century music, nationalism, the theory of modernism, and analysis. As a choral conductor he directed the Columbia...

called the work "anti-American, anti-Semitic and anti-bourgeois." Criticism continued when the production was released to DVD. In 2003, Edward Rothstein updated his stage review to a movie critique, writing "the film affirms two ideas now commonplace among radical critics of Israel: that Jews acted like Nazis, and that refugees from the Holocaust were instrumental in the founding of the state, visiting upon Palestinians the sins of others."

2003's The Dharma at Big Sur/ My Father Knew Charles Ives was well-received, particularly at Adams's alma mater's publication, the Harvard Crimson

Harvard Crimson

The Harvard Crimson are the athletic teams of Harvard University. The school's teams compete in NCAA Division I. As of 2006, there were 41 Division I intercollegiate varsity sports teams for women and men at Harvard, more than at any other NCAA Division I college in the country...

. In a four-star review, Harvard's newspaper called the electric violin and orchestral concerto "Adams's best composition of the past ten years." Most recently, New York Times writer Anthony Tommasini

Anthony Tommasini

-Early years:Tommasini was born in Brooklyn around 1948 and raised on Long Island. He was admitted to Oberlin College's Conservatory of Music, but chose to matriculate at Yale University in order to obtain a broader liberal arts education...

commended Adams for his work conducting the American Composers Orchestra. The concert, which took place in April 2007 at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, United States, located at 881 Seventh Avenue, occupying the east stretch of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street and West 57th Street, two blocks south of Central Park....

, was a celebratory performance of Adams's work on his sixtieth birthday. Tommasini called Adams a "skilled and dynamic conductor," and noted that the music "was gravely beautiful yet restless."

Arrangements

- (1989–93) Six Songs by Charles Ives (Ives'Charles IvesCharles Edward Ives was an American modernist composer. He is one of the first American composers of international renown, though Ives' music was largely ignored during his life, and many of his works went unperformed for many years. Over time, Ives came to be regarded as an "American Original"...

songs)

Awards and recognition

- Grammy AwardGrammy AwardA Grammy Award — or Grammy — is an accolade by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences of the United States to recognize outstanding achievement in the music industry...

for Best Contemporary Composition for Nixon in China (1989) - Royal Philharmonic SocietyRoyal Philharmonic SocietyThe Royal Philharmonic Society is a British music society, formed in 1813. It was originally formed in London to promote performances of instrumental music there. Many distinguished composers and performers have taken part in its concerts...

Music Award for Best Chamber Composition for Chamber Symphony (1994) - Grawemeyer AwardGrawemeyer AwardThe Grawemeyer Awards are five awards given annually by the University of Louisville in the state of Kentucky, United States. The prizes are presented to individuals in the fields of education, ideas improving world order, music composition, religion, and psychology...

in Musical Composition for Violin Concerto (1995) - Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and SciencesAmerican Academy of Arts and SciencesThe American Academy of Arts and Sciences is an independent policy research center that conducts multidisciplinary studies of complex and emerging problems. The Academy’s elected members are leaders in the academic disciplines, the arts, business, and public affairs.James Bowdoin, John Adams, and...

(1997) - Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1997)

- Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Composition for El Dorado (1998)

- Pulitzer Prize for MusicPulitzer Prize for MusicThe Pulitzer Prize for Music was first awarded in 1943. Joseph Pulitzer did not call for such a prize in his will, but had arranged for a music scholarship to be awarded each year...

for On the Transmigration of Souls (2003) - Grammy Award for Best Classical Album for On the Transmigration of Souls (2005)

- Grammy Award for Best Orchestral Performance for On the Transmigration of Souls (2005)

- Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition for On the Transmigration of Souls (2005)

- Harvard Arts Medal (2007)

- Honorary Doctorate of Arts from Northwestern UniversityNorthwestern UniversityNorthwestern University is a private research university in Evanston and Chicago, Illinois, USA. Northwestern has eleven undergraduate, graduate, and professional schools offering 124 undergraduate degrees and 145 graduate and professional degrees....

(2008) - California Governor's Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Arts

- Cyril Magnin Award for Outstanding Achievement in the Arts

- Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters)

Further reading

- John Adams. Halleluiah Junction: Composing an American Life (US: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, UK: Faber and FaberFaber and FaberFaber and Faber Limited, often abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in the UK, notable in particular for publishing a great deal of poetry and for its former editor T. S. Eliot. Faber has a rich tradition of publishing a wide range of fiction, non fiction, drama, film and music...

, 2008). Autobiography