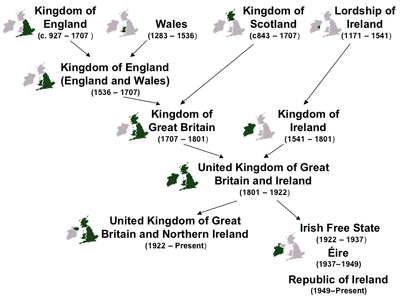

History of the formation of the United Kingdom

Encyclopedia

Personal union

A personal union is the combination by which two or more different states have the same monarch while their boundaries, their laws and their interests remain distinct. It should not be confused with a federation which is internationally considered a single state...

and political union

Political union

A political union is a type of state which is composed of or created out of smaller states. Unlike a personal union, the individual states share a common government and the union is recognized internationally as a single political entity...

across Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

and the wider British Isles

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

. The United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

is the most recent of a number of sovereign states that have been established in Great Britain at different periods in history, in different combinations and under a variety of polities

Polity

Polity is a form of government Aristotle developed in his search for a government that could be most easily incorporated and used by the largest amount of people groups, or states...

. Norman Davies

Norman Davies

Professor Ivor Norman Richard Davies FBA, FRHistS is a leading English historian of Welsh descent, noted for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland, and the United Kingdom.- Academic career :...

has counted sixteen different states over the past 2000 years.

By the start of the 16th century, the number of states in Great Britain had been reduced to two: the Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

(which included Wales and controlled Ireland) and the Kingdom of Scotland

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

. The Union of Crowns in 1603, the accidental consequence of a royal marriage one hundred years earlier, united the kingdoms in a personal union, though full political union in the form of the Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

required a Treaty of Union

Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name given to the agreement that led to the creation of the united kingdom of Great Britain, the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, which took effect on 1 May 1707...

in 1706 and Acts of Union

Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union were two Parliamentary Acts - the Union with Scotland Act passed in 1706 by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act passed in 1707 by the Parliament of Scotland - which put into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union that had been agreed on 22 July 1706,...

in 1707 (to ratify the Treaty). A further Act of Union

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

in 1800 included Ireland in the Union to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

. From the late 19th century, a growth in support for nationalist political parties, firstly in Ireland, and much later in Scotland and Wales, resulted in independence for most of the island of Ireland in 1922 and the establishment of devolved parliaments or assemblies for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

England's conquest of Wales

Through internal struggles and dynastic marriage alliances, the Welsh became more united until Owain GwyneddOwain Gwynedd

Owain Gwynedd ap Gruffydd , in English also known as Owen the Great, was King of Gwynedd from 1137 until his death in 1170. He is occasionally referred to as "Owain I of Gwynedd"; and as "Owain I of Wales" on account of his claim to be King of Wales. He is considered to be the most successful of...

(1100–1170) became the first Welsh ruler to use the title princeps Wallensium (prince of the Welsh). After invading England, land-hungry Normans

Normans

The Normans were the people who gave their name to Normandy, a region in northern France. They were descended from Norse Viking conquerors of the territory and the native population of Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock...

started pushing into the relatively weak Welsh Marches

Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches is a term which, in modern usage, denotes an imprecisely defined area along and around the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods...

, setting up a number of lordships in the Eastern part of the country and the border areas. In response, the usually fractious Welsh, who still retained control of the north and west of Wales, started to unite around leaders such as Owain Gwynedd's grandson Llywelyn the Great

Llywelyn the Great

Llywelyn the Great , full name Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, was a Prince of Gwynedd in north Wales and eventually de facto ruler over most of Wales...

, (1173–1240) who is known to have described himself as "prince of all North Wales". Llywelyn wrestled concessions out of the Magna Carta

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter, originally issued in the year 1215 and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions, which included the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority to date. The charter first passed into law in 1225...

in 1215 and received the fealty

Fealty

An oath of fealty, from the Latin fidelitas , is a pledge of allegiance of one person to another. Typically the oath is made upon a religious object such as a Bible or saint's relic, often contained within an altar, thus binding the oath-taker before God.In medieval Europe, fealty was sworn between...

of other Welsh lords in 1216 at the council at Aberdovey, becoming the first Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales is a title traditionally granted to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the 15 other independent Commonwealth realms...

. His grandson Llywelyn the Last

Llywelyn the Last

Llywelyn ap Gruffydd or Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf , sometimes rendered as Llywelyn II, was the last prince of an independent Wales before its conquest by Edward I of England....

also secured the recognition of the title Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales is a title traditionally granted to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the 15 other independent Commonwealth realms...

from Henry III

Henry III of England

Henry III was the son and successor of John as King of England, reigning for 56 years from 1216 until his death. His contemporaries knew him as Henry of Winchester. He was the first child king in England since the reign of Æthelred the Unready...

with the Treaty of Montgomery

Treaty of Montgomery

By means of the Treaty of Montgomery , Llywelyn ap Gruffydd was acknowledged as Prince of Wales by the English king Henry III, the only time in history that an English ruler would recognise the right of a ruler of Gwynedd over Wales...

in 1267. However, a succession of disputes, including the imprisonment of Llywelyn's wife Eleanor

Eleanor de Montfort

Eleanor de Montfort, Princess of Wales and Lady of Snowdon was a daughter of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester and Eleanor of England. She was also the first woman who can be shown to have used the title Princess of Wales....

, daughter of Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, 1st Earl of Chester , sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from other Simon de Montforts, was an Anglo-Norman nobleman. He led the barons' rebellion against King Henry III of England during the Second Barons' War of 1263-4, and...

, culminated in the first invasion by Edward I

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

. After a military defeat, the Treaty of Aberconwy

Treaty of Aberconwy

The Treaty of Aberconwy was signed in 1277 by King Edward I of England and Llewelyn the Last of modern-day Wales, who had fought each other on and off for years over control of the Welsh countryside...

imposed English fealty over Llywelyn in 1277.

In 1282, Edward I

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

finally conquered the last remaining native Welsh principalities in north and west Wales and across that area established the counties of Anglesey, Caernarfonshire

Caernarfonshire

Caernarfonshire , historically spelled as Caernarvonshire or Carnarvonshire in English during its existence, was one of the thirteen historic counties, a vice-county and a former administrative county of Wales....

, Flintshire

Flintshire (historic)

Flintshire , also known as the County of Flint, is one of thirteen historic counties, a vice-county and a former administrative county, which mostly lies on the north east coast of Wales....

, Merionethshire

Merionethshire

Merionethshire is one of thirteen historic counties of Wales, a vice county and a former administrative county.The administrative county of Merioneth, created under the Local Government Act 1888, was abolished under the Local Government Act 1972 on April 1, 1974...

, Cardiganshire

Ceredigion

Ceredigion is a county and former kingdom in mid-west Wales. As Cardiganshire , it was created in 1282, and was reconstituted as a county under that name in 1996, reverting to Ceredigion a day later...

and Carmarthenshire

Carmarthenshire

Carmarthenshire is a unitary authority in the south west of Wales and one of thirteen historic counties. It is the 3rd largest in Wales. Its three largest towns are Llanelli, Carmarthen and Ammanford...

. The Statute of Rhuddlan

Statute of Rhuddlan

The Statute of Rhuddlan , also known as the Statutes of Wales or as the Statute of Wales provided the constitutional basis for the government of the Principality of North Wales from 1284 until 1536...

formally established Edward's rule over Wales two years later although Welsh law continued to be used. Edward's son (later Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

), who had been born in Wales, was made Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales is a title traditionally granted to the heir apparent to the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the 15 other independent Commonwealth realms...

. The tradition of bestowing the style 'Prince of Wales' on the heir of the British Monarch continues to the present day. To help maintain his dominance, Edward constructed a series of great stone castle

Castle

A castle is a type of fortified structure built in Europe and the Middle East during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars debate the scope of the word castle, but usually consider it to be the private fortified residence of a lord or noble...

s.

Between 1284 and 1536, the Crown had only indirect control over Wales, as the Marcher lords (ruling over independent lordships in the east and south of Wales) were independent from direct Crown control. There was no major uprising except that led by Owain Glyndŵr

Owain Glyndwr

Owain Glyndŵr , or Owain Glyn Dŵr, anglicised by William Shakespeare as Owen Glendower , was a Welsh ruler and the last native Welshman to hold the title Prince of Wales...

a century later, against Henry IV of England

Henry IV of England

Henry IV was King of England and Lord of Ireland . He was the ninth King of England of the House of Plantagenet and also asserted his grandfather's claim to the title King of France. He was born at Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, hence his other name, Henry Bolingbroke...

. In 1404 Glyndŵr was crowned Prince of Wales in the presence of emissaries from France, Spain and Scotland; he went on to hold parliamentary assemblies at several Welsh towns, including Machynlleth

Machynlleth

Machynlleth is a market town in Powys, Wales. It is in the Dyfi Valley at the intersection of the A487 and the A489 roads.Machynlleth was the seat of Owain Glyndŵr's Welsh Parliament in 1404, and as such claims to be the "ancient capital of Wales". However, it has never held any official...

. The rebellion was ultimately to founder, however. Glyndŵr went into hiding in 1412, and peace was more or less restored in Wales by 1415. The power of the Marcher lords was ended in 1535, when the political and administrative union of England and Wales was completed. The Laws in Wales Act 1535 annexed Wales to the legal system of England, and partitioned the Marches into the counties of Brecon

Brecknockshire

Brecknockshire , also known as the County of Brecknock, Breconshire, or the County of Brecon is one of thirteen historic counties of Wales, and a former administrative county.-Geography:...

, Denbigh

Denbighshire (historic)

Historic Denbighshire is one of thirteen traditional counties in Wales, a vice-county and a former administrative county, which covers an area in north east Wales...

, Monmouth

Monmouthshire (historic)

Monmouthshire , also known as the County of Monmouth , is one of thirteen ancient counties of Wales and a former administrative county....

, Montgomery

Montgomeryshire

Montgomeryshire, also known as Maldwyn is one of thirteen historic counties and a former administrative county of Wales. Montgomeryshire is still used as a vice-county for wildlife recording...

and Radnor

Radnorshire

Radnorshire is one of thirteen historic and former administrative counties of Wales. It is represented by the Radnorshire area of Powys, which according to the 2001 census, had a population of 24,805...

while adding parts to Gloucester

Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn, and the entire Forest of Dean....

, Hereford

Herefordshire

Herefordshire is a historic and ceremonial county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes it is a NUTS 3 region and is one of three counties that comprise the "Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Gloucestershire" NUTS 2 region. It also forms a unitary district known as the...

and Salop

Shropshire

Shropshire is a county in the West Midlands region of England. For Eurostat purposes, the county is a NUTS 3 region and is one of four counties or unitary districts that comprise the "Shropshire and Staffordshire" NUTS 2 region. It borders Wales to the west...

. (The subsequent Laws in Wales Act of 1542 made no mention of Monmouthshire, which led to ambiguity about its status as part of England or Wales.) The Act also extended the Law of England to both England and Wales, and made English the only permissible language for official purposes. This excluded most native Welsh people from formal office. Wales was also now represented in Parliament at Westminster.

English lordship over Ireland

By the 12th century, IrelandIreland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

was divided. Power was exercised by the heads of a few regional dynasties vying with each other for supremacy over the whole island. In 1155 Pope Adrian IV issued the papal bull Laudabiliter

Laudabiliter

Laudabiliter was a papal bull issued in 1155 by Adrian IV, the only Englishman to serve as Pope, giving the Angevin King Henry II of England the right to assume control over Ireland and apply the Gregorian Reforms in the Irish church...

giving the Norman King Henry II of England

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

lordship over Ireland. The bull granted Henry the right to invade Ireland in order to reform Church practices. When the King of Leinster

Leinster

Leinster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the east of Ireland. It comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Mide, Osraige and Leinster. Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the historic fifths of Leinster and Mide gradually merged, mainly due to the impact of the Pale, which straddled...

Diarmuid MacMorroug was forcibly exiled from his kingdom by the new High King, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair, he obtained permission from Henry II of England

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

to use Norman

Normans

The Normans were the people who gave their name to Normandy, a region in northern France. They were descended from Norse Viking conquerors of the territory and the native population of Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock...

forces to regain his kingdom. The Normans

Normans

The Normans were the people who gave their name to Normandy, a region in northern France. They were descended from Norse Viking conquerors of the territory and the native population of Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock...

landed in Ireland in 1169 and within a short time Leinster was reclaimed by Diarmait, who named his son-in-law, Richard de Clare

Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke

Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke , Lord of Leinster, Justiciar of Ireland . Like his father, he was also commonly known as Strongbow...

, heir to his kingdom. This caused consternation to Henry

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland.

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland") in 1185. When John unexpectedly became King of England, the Lordship of Ireland fell directly under the English Crown. The title of Lord of Ireland and King of England fell into personal union. Throughout the 13th century the policy of the English Kings was to weaken the power of the Norman Lords

Norman Ireland

The History of Ireland 1169–1536 covers the period from the arrival of the Cambro-Normans to the reign of Henry VIII of England, who made himself King of Ireland. After the Norman invasion of 1171, Ireland was under an alternating level of control from Norman lords and the King of England...

in Ireland.

There was a resurgence of Gaelic

Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland is the name given to the period when a Gaelic political order existed in Ireland. The order continued to exist after the arrival of the Anglo-Normans until about 1607 AD...

power as rebellious attacks stretched Norman resources. Politics and events in Gaelic Ireland also served to draw the settlers deeper into the orbit of the Irish. When the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

arrived in Ireland in 1348 it hit the English and Norman inhabitants who lived in towns and villages far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the countryside again. The English-controlled area shrunk back to the Pale

The Pale

The Pale or the English Pale , was the part of Ireland that was directly under the control of the English government in the late Middle Ages. It had reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast stretching from Dalkey, south of Dublin, to the garrison town of Dundalk...

, a fortified area around Dublin.

Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman lords adopted the Irish language and customs. Over the following centuries they sided with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts with England and generally stayed Catholic after the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

. The authorities in the Pale grew so worried about the "Gaelicisation" of Ireland that they passed special legislation banning those of English descent from speaking the Irish language, wearing Irish clothes or inter-marrying with the Irish. Since the government in Dublin had little real authority, however, the Statutes did not have much effect. By the end of the 15th century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared.

In 1532, Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

broke with Papal

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

authority. While the English, the Welsh and Scots accepted Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

, the Irish remained Catholic. This affected Ireland's relationship with England for the next four hundred years, as the English tried to re-conquer and colonise Ireland to prevent Ireland being a base for Catholic forces that were trying to overthrow the Protestant settlement in England.

In 1536, Henry VIII decided to re-conquer Ireland and bring it under Crown control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England. In 1541, he upgraded Ireland from a lordship to a full kingdom. Henry was proclaimed King of Ireland

King of Ireland

A monarchical polity has existed in Ireland during three periods of its history, finally ending in 1801. The designation King of Ireland and Queen of Ireland was used during these periods...

at a meeting of the Irish Parliament. With the institutions of government in place, the next step was to extend the control of the English Kingdom of Ireland over all of its claimed territory. The re-conquest was completed during the reigns of Elizabeth

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

and James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

, after several bloody conflicts. However, the English were not successful in converting the Catholic Irish to the Protestant religion and the brutal methods used by Crown authority to pacify the country heightened resentment of English rule.

From the mid-16th and into the early 17th century, Crown governments carried out a policy of colonisation

Colonisation

Colonization occurs whenever any one or more species populate an area. The term, which is derived from the Latin colere, "to inhabit, cultivate, frequent, practice, tend, guard, respect", originally related to humans. However, 19th century biogeographers dominated the term to describe the...

known as Plantations

Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th and 17th century Ireland were the confiscation of land by the English crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from England and the Scottish Lowlands....

. Scottish and English Protestants were sent as colonists to the provinces of Munster

Munster

Munster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the south of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes...

, Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

and the counties of Laois and Offaly. These settlers, who had a British and Protestant identity, would form the ruling class of future British administrations in Ireland. A series of Penal Laws discriminated against all faiths other than the established (Anglican) Church of Ireland

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland is an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. The church operates in all parts of Ireland and is the second largest religious body on the island after the Roman Catholic Church...

.

Personal Union: Union of the Crowns

In August 1503 James IVJames IV of Scotland

James IV was King of Scots from 11 June 1488 to his death. He is generally regarded as the most successful of the Stewart monarchs of Scotland, but his reign ended with the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Flodden Field, where he became the last monarch from not only Scotland, but also from all...

, King of Scots, married Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor was the elder of the two surviving daughters of Henry VII of England and Elizabeth of York, and the elder sister of Henry VIII. In 1503, she married James IV, King of Scots. James died in 1513, and their son became King James V. She married secondly Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of...

, the eldest daughter of Henry VII of England

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

. Almost 100 years later, when Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

was in the last decade of her reign, it was clear to all that James of Scots, the great-grandson of James IV and Margaret Tudor, was the only generally acceptable heir to the English throne. From 1601, Elizabeth I's chief minister Sir Robert Cecil

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, KG, PC was an English administrator and politician.-Life:He was the son of William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley and Mildred Cooke...

, maintained a secret correspondence with James in order to prepare in advance for a smooth succession. Elizabeth died on March, 24 1603 and James was proclaimed king in London later the same day. Despite sharing a monarchy, Scotland and England continued as separate countries with separate parliaments for over one hundred more years.

James had the idealistic ambition of building on the personal union of the crowns of Scotland and England so as to establish a permanent Union of the Crowns

Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns was the accession of James VI, King of Scots, to the throne of England, and the consequential unification of Scotland and England under one monarch. The Union of Crowns followed the death of James' unmarried and childless first cousin twice removed, Queen Elizabeth I of...

under one monarch, one parliament and one law. He insisted that English and Scots should "join and coalesce together in a sincere and perfect union, as two twins bred in one belly, to love one another as no more two but one estate". James's ambitions were greeted with very little enthusiasm, as one by one members of parliament rushed to defend the ancient name and realm of England. All sorts of legal objections were raised: all laws would have to be renewed and all treaties renegotiated. For James, whose experience of parliaments was limited to the stage-managed and semi-feudal Scottish variety, the self-assurance — and obduracy — of the English version, which had long experience of upsetting monarchs, was an obvious shock. The Scots were no more enthusiastic than the English, as they feared being reduced to the status of Wales or Ireland. In October 1604, James assumed the title "King of Great Britain" by proclamation rather than statute, although Sir Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England...

told him he could not use the style in "any legal proceeding, instrument or assurance". The two realms continued to maintain separate parliaments. The Union of the Crowns

Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns was the accession of James VI, King of Scots, to the throne of England, and the consequential unification of Scotland and England under one monarch. The Union of Crowns followed the death of James' unmarried and childless first cousin twice removed, Queen Elizabeth I of...

had begun a process that would lead to the eventual unification of the two kingdoms. However, in the ensuing hundred years, strong religious and political differences continued to divide the kingdoms, and common royalty could not prevent occasions of internecine warfare.

James did not create a British Crown, but he did, in one sense at least, create the British as a distinct group of people. In 1607 large tracts of land in Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

fell to the crown. A new Plantation was started, made up of Protestant settlers from Scotland and England. Over the years the settlers, surrounded by the hostile Catholic Irish, gradually cast off their separate English and Scottish roots, becoming British in the process, as a means of emphasising their 'otherness' from their Gaelic

Gaels

The Gaels or Goidels are speakers of one of the Goidelic Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Goidelic speech originated in Ireland and subsequently spread to western and northern Scotland and the Isle of Man....

neighbors. It was the one corner of the British Isles where Britishness became truly meaningful as a political and cultural identity in its own right, as opposed to a gloss on older and deeper national associations.

Ruling over the diverse kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland proved difficult for James and his successor Charles

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, particularly when they tried to impose religious uniformity on the Three Kingdoms. There were different religious conditions in each country. King Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

had made himself head of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

which was reformed under Edward VI

Edward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

and became Anglican under Elizabeth I. Protestantism became intimately associated with national identity in England. Roman Catholicism was seen as the national enemy, especially as embodied in France and Spain. However, Catholicism remained the religion of most people in Ireland and became a symbol of native resistance to the Tudor re-conquest of Ireland in the 16th century. Scotland had a national church, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland, known informally by its Scots language name, the Kirk, is a Presbyterian church, decisively shaped by the Scottish Reformation....

, although much of the highlands

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

remained Catholic. With the support of the Episcopalians

Episcopal polity

Episcopal polity is a form of church governance that is hierarchical in structure with the chief authority over a local Christian church resting in a bishop...

, James reintroduced bishops into the Church of Scotland against the wishes of the presbyterian party.

In 1625, James was succeeded by his son Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

, who in 1633, some years after his coronation

Coronation

A coronation is a ceremony marking the formal investiture of a monarch and/or their consort with regal power, usually involving the placement of a crown upon their head and the presentation of other items of regalia...

at Westminster

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

, was crowned in St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, with full Anglican rites. Opposition to his attempts to enforce Anglican practices reached a flashpoint when he tried to introduce a Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

. Charles's confrontation with the Scots came to a head in 1639, when he tried and failed to coerce Scotland by military means. In some respects, this revolt also represented Scottish resentment at being sidelined within the Stuart monarchy after James I's accession to the throne of England. It led to the Bishop's Wars.

Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

's accession also marked the beginning of an intense schism between King and Parliament. Charles's adherence to the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings

Divine Right of Kings

The divine right of kings or divine-right theory of kingship is a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy. It asserts that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority, deriving his right to rule directly from the will of God...

, a doctrine foreign to the English mentality which he had inherited from his father, fuelled a vicious battle for supremacy between king and Parliament. So when Charles approached the Parliament to pay for a campaign against the Scots, they refused, declared themselves to be permanently in session and put forward a long list of civil and religious grievances that Charles would have to remedy before they approved any new legislation. Meanwhile, in the Kingdom of Ireland, Charles I's Lord Deputy there, Thomas Wentworth

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford

Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford was an English statesman and a major figure in the period leading up to the English Civil War. He served in Parliament and was a supporter of King Charles I. From 1632 to 1639 he instituted a harsh rule as Lord Deputy of Ireland...

, had antagonised the native Irish Catholics by repeated initiatives to confiscate their lands and grant them to English colonists. He had also angered them by enforcing new taxes but denying Roman Catholics full rights as subjects. What made this situation explosive was his idea, in 1639, to offer Irish Catholics the reforms they had been looking for in return for them raising and paying for an Irish army to put down the Scottish rebellion. Although the army was to be officered by Protestants, the idea of an Irish Catholic army being used to enforce what was seen by many as tyrannical government horrified both the Scottish and the English Parliament, who in response threatened to invade Ireland.

Alienated by British Protestant domination and frightened by the rhetoric of the English and Scottish Parliaments, a small group of Irish conspirators launched the Irish Rebellion of 1641

Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

, ostensibly in support of the "King's Rights". The rising was marked by widespread assaults on the British Protestant communities in Ireland, sometimes culminating in massacres. Rumours spread in England and Scotland that the killings had the King's sanction and that this was a foretaste of what was in store for them if the King's Irish troops landed in Britain. As a result, the English Parliament refused to pay for a royal army to put down the rebellion in Ireland and instead raised its own armed forces. The King did likewise, rallying those Royalists

Cavalier

Cavalier was the name used by Parliamentarians for a Royalist supporter of King Charles I and son Charles II during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration...

(some of them members of Parliament) who believed that loyalty to the legitimate King was the most important political principle.

The English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

broke out in 1642. The Scottish Covenanter

Covenanter

The Covenanters were a Scottish Presbyterian movement that played an important part in the history of Scotland, and to a lesser extent in that of England and Ireland, during the 17th century...

s, as the Presbyterians called themselves, sided with the English Parliament, joined the war in 1643, and played a major role in the English Parliamentary victory. The King's forces were ground down by the efficiency of Parliament's New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

- backed by the financial muscle of the City of London

City of London

The City of London is a small area within Greater London, England. It is the historic core of London around which the modern conurbation grew and has held city status since time immemorial. The City’s boundaries have remained almost unchanged since the Middle Ages, and it is now only a tiny part of...

. In 1646, Charles I surrendered. After failing to come to compromise with Parliament, he was arrested and executed in 1649. In Ireland, the rebel Irish Catholics formed their own government - Confederate Ireland with the intention of helping the Royalists in return for religious toleration and political autonomy. Troops from England and Scotland fought in Ireland, and Irish Confederate troops mounted an expedition to Scotland in 1644, sparking the Scottish Civil War

Scottish Civil War

Between 1644 and 1651 Scotland was involved the Wars of the Three Kingdoms during a period when a series of civil wars that were fought in Scotland, England and in Ireland...

. In Scotland, the Royalists had a series of victories in 1644-45, but were crushed with the end of the first English Civil War and the return of the main Covenanter armies to Scotland.

After the end of the second English Civil War, the victorious Parliamentary forces, now commanded by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

, invaded Ireland and crushed the Royalist-Confederate alliance there in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in 1649. Their alliance with the Scottish Covenanters had also broken down, and the Scots crowned Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

as king. Cromwell therefore embarked on a conquest of Scotland in 1650-51. By the end of the wars, the Three Kingdoms were a unitary state called the English Commonwealth

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the republic which ruled first England, and then Ireland and Scotland from 1649 to 1660. Between 1653–1659 it was known as the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland...

, ostensibly a republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

, but having many characteristics of a military dictatorship

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

.

While the Wars of the Three Kingdoms pre-figured many of the changes that would shape modern Britain, in the short term it resolved little. The English Commonwealth

Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth of England was the republic which ruled first England, and then Ireland and Scotland from 1649 to 1660. Between 1653–1659 it was known as the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland...

did achieve a compromise (though a relatively unstable one) between a monarchy and a republic. In practise power was exercised by Oliver Cromwell because of his control over the Parliament's military forces, but his legal position was never clarified, even when he became Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

. While several constitutions were proposed, none were ever accepted. Thus the Commonwealth and the Protectorate

The Protectorate

In British history, the Protectorate was the period 1653–1659 during which the Commonwealth of England was governed by a Lord Protector.-Background:...

established by the victorious Parliamentarians left little behind it in the way of new forms of government. There were two important legacies from this period, the first was that in executing King Charles I for high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

, no future British monarch could be under any illusion that perceived despotism would be tolerated; and the excesses of Army rule, particularly that of the Major-Generals, has left an abiding mistrust of military rule in the English speaking world.

Ireland and Scotland were occupied by the New Model Army during the Interregnum. In Ireland, almost all lands belonging to Irish Catholics were confiscated as punishment for the rebellion of 1641; harsh Penal Laws were also passed against this community. Thousands of Parliamentarian soldiers were settled in Ireland on confiscated lands. The Parliaments of Ireland and Scotland were abolished. In theory, they were represented in the English Parliament, but since this body was never given real powers, this was insignificant. When Cromwell died in 1658, the Commonwealth fell apart, without major violence and Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

was restored as King of England, Scotland and Ireland.

Under the English Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

, the political system returned to the constitutional position of before the wars: Scotland and Ireland were returned their Parliaments.

When Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

died his Catholic brother James

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

inherited the throne as James II of England and VII of Scotland. When he had a son, the Parliament of England decided to depose him in the Glorious Revolution

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

of 1688. He was replaced not by his Roman Catholic son, James Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward, Prince of Wales was the son of the deposed James II of England...

, but by his Protestant daughter and son-in-law, Mary II

Mary II of England

Mary II was joint Sovereign of England, Scotland, and Ireland with her husband and first cousin, William III and II, from 1689 until her death. William and Mary, both Protestants, became king and queen regnant, respectively, following the Glorious Revolution, which resulted in the deposition of...

and William III

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

, who became joint rulers in 1689. James made one serious attempt to recover his crowns, which ended with defeat at the Battle of the Boyne

Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690 between two rival claimants of the English, Scottish and Irish thronesthe Catholic King James and the Protestant King William across the River Boyne near Drogheda on the east coast of Ireland...

in 1690.

Acts of Union 1707

Deeper political integration was a key policy of Queen AnneAnne of Great Britain

Anne ascended the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland on 8 March 1702. On 1 May 1707, under the Act of Union, two of her realms, England and Scotland, were united as a single sovereign state, the Kingdom of Great Britain.Anne's Catholic father, James II and VII, was deposed during the...

, (1702–14), who succeeded to the throne in 1702 as the last Stuart monarch of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

(she became the only Stuart monarch of Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

). The Queen appointed Commissioners for the union on the part of Scotland and England respectively, and in 1706 they began negotiations in earnest, with agreement reached on the terms of a Treaty of Union

Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name given to the agreement that led to the creation of the united kingdom of Great Britain, the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, which took effect on 1 May 1707...

on July 22, 1706, The circumstances of Scotland's acceptance of the Bill are to some degree disputed. Scottish proponents believed that failure to accede to the Bill would result in the imposition of Union under less favourable terms and the Lord Justice Clerk

Lord Justice Clerk

The Lord Justice Clerk is the second most senior judge in Scotland, after the Lord President of the Court of Session.The holder has the title in both the Court of Session and the High Court of Justiciary and is in charge of the Second Division of Judges in the Court of Session...

, James Johnstone later observed that "As for giving up the legislative power, we had none to give up... For the true state of the matter was whether Scotland should be subject to an English ministry without the privilege of trade or be subject to an English Parliament with trade." Months of fierce debate on both sides of the border were to follow, particularly in Scotland where debate could often dissolve into civil disorder, most notably by the notorious 'Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

Mob'. The prospect of a Union of the kingdoms was deeply unpopular among the Scottish population at large, however following the financially disastrous Darien Scheme

Darién scheme

The Darién scheme was an unsuccessful attempt by the Kingdom of Scotland to become a world trading nation by establishing a colony called "New Caledonia" on the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s...

, the near-bankrupt Parliament of Scotland

Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland, officially the Estates of Parliament, was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland. The unicameral parliament of Scotland is first found on record during the early 13th century, with the first meeting for which a primary source survives at...

did accept the proposals.

In 1707, the Acts of Union received their Royal assent

Royal Assent

The granting of royal assent refers to the method by which any constitutional monarch formally approves and promulgates an act of his or her nation's parliament, thus making it a law...

, thereby abolishing the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland and their respective parliaments to create a unified Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

with a single Parliament of Great Britain. Anne became formally the first occupant of the unified British throne and Scotland sent 45 MPs to the new parliament at Westminster. Perhaps the greatest single benefit to Scotland of the Union was that Scotland could enjoy free trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

with England and her colonies overseas. For England's part, a possible ally for European states hostile to England had been neutralised while simultaneously securing a Protestant succession to the British throne.

However, certain aspect of the former independent kingdoms remained separate. Examples of Scottish and English institutions which were not merged into the British system include: Scottish

Scots law

Scots law is the legal system of Scotland. It is considered a hybrid or mixed legal system as it traces its roots to a number of different historical sources. With English law and Northern Irish law it forms the legal system of the United Kingdom; it shares with the two other systems some...

and English law

English law

English law is the legal system of England and Wales, and is the basis of common law legal systems used in most Commonwealth countries and the United States except Louisiana...

which remain separate, as do Scottish

Bank of Scotland

The Bank of Scotland plc is a commercial and clearing bank based in Edinburgh, Scotland. With a history dating to the 17th century, it is the second oldest surviving bank in what is now the United Kingdom, and is the only commercial institution created by the Parliament of Scotland to...

and English

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694, it is the second oldest central bank in the world...

banking systems, the Presbyterian Church of Scotland

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland, known informally by its Scots language name, the Kirk, is a Presbyterian church, decisively shaped by the Scottish Reformation....

and Anglican Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

also remained separate as did the systems of education and higher learning.

Having failed to establish their own empire, but being better educated than the average Englishman, the Scots made a distinguished and disproportionate contribution to both the government of the United Kingdom and the administration of the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

.

Acts of Union 1800

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

, Irish Catholics were barred from voting or attending the Irish Parliament

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

. The new English Protestant ruling class was known as the Protestant Ascendancy

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

. Towards the end of the 18th century the entirely Protestant Irish Parliament attained a greater degree of independence from the British Parliament than it had previously held. Under the Penal Laws

Penal Laws (Ireland)

The term Penal Laws in Ireland were a series of laws imposed under English and later British rule that sought to discriminate against Roman Catholics and Protestant dissenters in favour of members of the established Church of Ireland....

no Irish Catholic could sit in the Parliament of Ireland

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

, even though some 90% of Ireland's population was native Irish Catholic when the first of these bans was introduced in 1691. This ban was followed by others in 1703 and 1709 as part of a comprehensive system disadvantaging the Catholic community, and to a lesser extent Protestant dissenters. In 1798, many members of this dissenter tradition made common cause with Catholics in a rebellion inspired and led by the Society of United Irishmen. It was staged with the aim of creating a fully independent Ireland as a state with a republican constitution. Despite assistance from France the Irish Rebellion of 1798

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 , also known as the United Irishmen Rebellion , was an uprising in 1798, lasting several months, against British rule in Ireland...

was put down by British forces.

The legislative union of Great Britain and Ireland was completed by the Acts of Union 1800 passed by each parliament, united the two kingdoms into one, called "The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

". The twin Acts were passed in the Parliament of Great Britain

Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and Parliament of Scotland...

and the Parliament of Ireland

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

with substantial majorities achieved in Ireland in part (according to contemporary documents) through bribery

Bribery

Bribery, a form of corruption, is an act implying money or gift giving that alters the behavior of the recipient. Bribery constitutes a crime and is defined by Black's Law Dictionary as the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value to influence the actions of an official or...

, namely the awarding of peerage

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

s and honour

Honour

Honour or honor is an abstract concept entailing a perceived quality of worthiness and respectability that affects both the social standing and the self-evaluation of an individual or corporate body such as a family, school, regiment or nation...

s to critics to get their votes.

Under the terms of the union, there was to be but one Parliament of the United Kingdom

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

. Ireland sent four lords spiritual (bishops) and twenty-eight lords temporal to the House of Lords and on hundred members to the House of Commons at Westminster. The lords spiritual were chosen by rotation and the lords temporal were elected from among the peers of Ireland.

Part of the arrangement as a trade-off for Irish Catholics was to be the granting of Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

, which had been fiercely resisted by the all-Anglican Irish Parliament. However, this was blocked by King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

who argued that emancipating Roman Catholics would breach his Coronation Oath. The Roman Catholic hierarchy had endorsed the Union. However the decision to block Catholic Emancipation fatally undermined the appeal of the Union.

Irish alienation and independence

The 19th century saw the Great Famine of the 1840s, during which one million Irish peopleIrish people

The Irish people are an ethnic group who originate in Ireland, an island in northwestern Europe. Ireland has been populated for around 9,000 years , with the Irish people's earliest ancestors recorded having legends of being descended from groups such as the Nemedians, Fomorians, Fir Bolg, Tuatha...

died and over a million emigrated. Aspects of the United Kingdom met with popularity in Ireland during the 122 year union. Hundreds of thousands flocked to Dublin for the visits of Queen Victoria in 1900, King Edward VII

Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

and Queen Alexandra in 1903 and 1907 and King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

and Queen Mary

Mary of Teck

Mary of Teck was the queen consort of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, as the wife of King-Emperor George V....

in 1911. About 210,000 Irishmen fought for the United Kingdom in World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, at a time when Ireland was the only home nation where conscription was not in force.

The 19th century and early 20th century saw the rise of Irish Nationalism

Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism manifests itself in political and social movements and in sentiment inspired by a love for Irish culture, language and history, and as a sense of pride in Ireland and in the Irish people...

especially among the Catholic population. From the General Election of 1874 until the creation of the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

in 1922, the majority of MPs elected from Irish constituencies supported Home Rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

, sometimes finding themselves holding the balance of power in the House of Commons. Frustrated by lack of political progress, an armed rebellion took place with the Easter Rising

Easter Rising

The Easter Rising was an insurrection staged in Ireland during Easter Week, 1916. The Rising was mounted by Irish republicans with the aims of ending British rule in Ireland and establishing the Irish Republic at a time when the British Empire was heavily engaged in the First World War...

of 1916. Two years later, the more radical, republican party, Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin is a left wing, Irish republican political party in Ireland. The name is Irish for "ourselves" or "we ourselves", although it is frequently mistranslated as "ourselves alone". Originating in the Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, it took its current form in 1970...

, won 73 of the 103 Irish constituencies. Sinn Féin had promised not to sit in the UK Parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

but rather to set up an Irish Parliament', known as the First Dáil

First Dáil

The First Dáil was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 1919–1921. In 1919 candidates who had been elected in the Westminster elections of 1918 refused to recognise the Parliament of the United Kingdom and instead assembled as a unicameral, revolutionary parliament called "Dáil Éireann"...

which declared Irish independence by reaffirming the 1916 declaration, leading to the subsequent Irish War of Independence

Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence , Anglo-Irish War, Black and Tan War, or Tan War was a guerrilla war mounted by the Irish Republican Army against the British government and its forces in Ireland. It began in January 1919, following the Irish Republic's declaration of independence. Both sides agreed...

. In 1921, a treaty was concluded between the British Government and the leaders of the Irish Republic

Irish Republic

The Irish Republic was a revolutionary state that declared its independence from Great Britain in January 1919. It established a legislature , a government , a court system and a police force...

. The Treaty recognised the two-state solution created in the Government of Ireland Act 1920

Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was the Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which partitioned Ireland. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill or as the Fourth Home Rule Act.The Act was intended...

. Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom. Situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, it shares a border with the Republic of Ireland to the south and west...

would form a home rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

state within the new Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

unless it opted out. Northern Ireland had a majority Protestant population and opted out as expected. A Boundary Commission

Boundary Commission (Ireland)

The Irish Boundary Commission was a commission which met in 1924–25 to decide on the precise delineation of the border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland...

was set up to decide on the border between the two Irish states, though it was subsequently abandoned after it recommended only minor adjustments to the border.

The Irish Free State was initially a British Empire Dominion like Canada and South Africa with King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

being titled King of Ireland

King of Ireland

A monarchical polity has existed in Ireland during three periods of its history, finally ending in 1801. The designation King of Ireland and Queen of Ireland was used during these periods...

. Along with the other dominions it received legal independence in 1931 under the Statute of Westminster 1931

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

. It became a republic in 1949

Republic of Ireland Act

The Republic of Ireland Act 1948 is an Act of the Oireachtas which declared the Irish state to be a republic, and vested in the President of Ireland the power to exercise the executive authority of the state in its external relations, on the advice of the Government of Ireland...

and left the British Commonwealth, without constitutional ties with the United Kingdom.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland continued in name until 1927 when it was renamed the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland by the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927

Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927

The Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act 1927 [17 & 18 Geo. 5 c. 4] was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that authorised the alteration of the British monarch's royal style and titles, and altered the formal name of the British Parliament, in recognition of much of Ireland separating from...

(albeit that strictly speaking the Act only referred to the King's title and the name of Parliament).

Despite increasing political independence from each other from 1922, and complete political independence since 1949, the union left the two countries intertwined with each other in many respects. Ireland used the Irish Pound

Irish pound

The Irish pound was the currency of Ireland until 2002. Its ISO 4217 code was IEP, and the usual notation was the prefix £...

from 1928 until 2001 when it was replaced by the Euro

Euro

The euro is the official currency of the eurozone: 17 of the 27 member states of the European Union. It is also the currency used by the Institutions of the European Union. The eurozone consists of Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg,...

. Until it joined the ERM in 1979, the Irish pound was directly linked to the Pound Sterling

Pound sterling

The pound sterling , commonly called the pound, is the official currency of the United Kingdom, its Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and Tristan da Cunha. It is subdivided into 100 pence...

. Decimalisation

Decimalisation

Decimal currency is the term used to describe any currency that is based on one basic unit of currency and a sub-unit which is a power of 10, most commonly 100....

of both currencies occurred simultaneously on Decimal Day

Decimal Day

Decimal Day was the day the United Kingdom and Ireland decimalised their currencies.-Old system:Under the old currency of pounds, shillings and pence, the pound was made up of 240 pence , with 12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings in a...