History of the Republic of China

Encyclopedia

- For the history of ChinaChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

/ Mainland ChinaMainland ChinaMainland China, the Chinese mainland or simply the mainland, is a geopolitical term that refers to the area under the jurisdiction of the People's Republic of China . According to the Taipei-based Mainland Affairs Council, the term excludes the PRC Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and...

, see History of ChinaHistory of ChinaChinese civilization originated in various regional centers along both the Yellow River and the Yangtze River valleys in the Neolithic era, but the Yellow River is said to be the Cradle of Chinese Civilization. With thousands of years of continuous history, China is one of the world's oldest...

and History of People's Republic of China.

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

in 1912, when the formation of the Republic of China

Republic of China (1912–1949)

In 1911, after over two thousand years of imperial rule, a republic was established in China and the monarchy overthrown by a group of revolutionaries. The Qing Dynasty, having just experienced a century of instability, suffered from both internal rebellion and foreign imperialism...

put an end to over two thousand years of Imperial rule. The Qing Dynasty, also known as the Manchu Dynasty, ruled from 1644 to 1912. Since the republic's founding, it has experienced many tribulations as it was dominated by numerous warlords

Warlord era

The Chinese Warlord Era was the period in the history of the Republic of China, from 1916 to 1928, when the country was divided among military cliques, a division that continued until the fall of the Nationalist government in the mainland China regions of Sichuan, Shanxi, Qinghai, Ningxia,...

and fragmented by foreign powers.

In 1928, the republic was nominally unified under the Kuomintang

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang of China , sometimes romanized as Guomindang via the Pinyin transcription system or GMD for short, and translated as the Chinese Nationalist Party is a founding and ruling political party of the Republic of China . Its guiding ideology is the Three Principles of the People, espoused...

(KMT, the Chinese Nationalist Party) after the Northern Expedition, and was in the early stages of industrialization and modernization when it was caught in the conflicts between the Kuomintang government, the Communist Party of China

Communist Party of China

The Communist Party of China , also known as the Chinese Communist Party , is the founding and ruling political party of the People's Republic of China...

which was converted into a nationalist party, remnant warlords, and Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

. Most nation-building efforts were stopped during the full-scale War of Resistance

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

against Japan from 1937 to 1945, and later the widening gap between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party made a coalition government impossible, causing the resumption of the Chinese Civil War

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was a civil war fought between the Kuomintang , the governing party of the Republic of China, and the Communist Party of China , for the control of China which eventually led to China's division into two Chinas, Republic of China and People's Republic of...

.

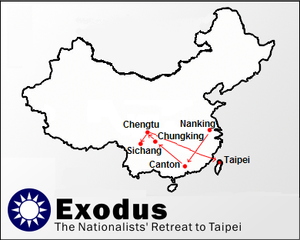

A series of political, economic, and military missteps led the Kuomintang to defeat and retreat to Taiwan

Taiwan

Taiwan , also known, especially in the past, as Formosa , is the largest island of the same-named island group of East Asia in the western Pacific Ocean and located off the southeastern coast of mainland China. The island forms over 99% of the current territory of the Republic of China following...

in 1949, establishing an authoritarian one-party state

Single-party state

A single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a type of party system government in which a single political party forms the government and no other parties are permitted to run candidates for election...

that considered itself to be the sole legitimate ruler of all of China. However, since political liberalization began in the late 1970s, the Republic of China has transformed itself into a multiparty, representative democracy on Taiwan.

Founding of the republic

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

were marked by civil unrest and foreign invasions. Various internal rebellions caused millions of deaths, and conflicts with foreign powers almost always resulted in humiliating unequal treaties

Unequal Treaties

“Unequal treaty” is a term used in specific reference to a number of treaties imposed by Western powers, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, on Qing Dynasty China and late Tokugawa Japan...

that exacted costly reparation

War reparations

War reparations are payments intended to cover damage or injury during a war. Generally, the term war reparations refers to money or goods changing hands, rather than such property transfers as the annexation of land.- History :...

and compromised the country's territorial integrity. In addition, there were feelings that political power should return to the majority Han Chinese

Han Chinese

Han Chinese are an ethnic group native to China and are the largest single ethnic group in the world.Han Chinese constitute about 92% of the population of the People's Republic of China , 98% of the population of the Republic of China , 78% of the population of Singapore, and about 20% of the...

from the minority Manchus.

Responding to these civil failures and discontent, the Qing Imperial Court did attempt to reform the government in various ways, such as the decision to draft a constitution in 1906, the establishment of provincial legislatures in 1909, and the preparation for a national parliament in 1910. However, many of these measures were opposed by the conservatives of the Qing Court, and many reformers were either imprisoned or executed outright. The failures of the Imperial Court to enact such reforming measures of political liberalization and modernization caused the reformists to steer toward the road of revolution.

There were many revolutionary groups, but the most organized one was founded by Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen was a Chinese doctor, revolutionary and political leader. As the foremost pioneer of Nationalist China, Sun is frequently referred to as the "Father of the Nation" , a view agreed upon by both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China...

, a republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

an and anti-Qing activist who became increasingly popular among the overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese are people of Chinese birth or descent who live outside the Greater China Area . People of partial Chinese ancestry living outside the Greater China Area may also consider themselves Overseas Chinese....

and Chinese students abroad, especially in Japan. In 1905 Sun founded the Tongmenghui

Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui, also known as the Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance and United Allegiance Society, was a secret society and underground resistance movement formed when merging many Chinese revolutionary groups together by Sun Yat-sen, Song...

in Tokyo with Huang Xing

Huang Xing

Huang Xing or Huang Hsing , was a Chinese revolutionary leader, militarist, and statesman, was the first army commander-in-chief of the Republic of China. As one of the founders of the Kuomintang and the Republic of China, his position was next to Sun Yat-sen. Together they were known as...

, a popular leader of the Chinese revolutionary movement in Japan, as his deputy.

This movement, generously supported by overseas Chinese funds, also gained political support with regional military officers and some of the reformers who had fled China after the Hundred Days' Reform

Hundred Days' Reform

The Hundred Days' Reform was a failed 104-day national cultural, political and educational reform movement from 11 June to 21 September 1898 in late Qing Dynasty China. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emperor and his reform-minded supporters...

. Sun's political philosophy was conceptualized in 1897, first enunciated in Tokyo in 1905, and modified through the early 1920s. It centered on the Three Principles of the People

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People, also translated as Three People's Principles, or collectively San-min Doctrine, is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to make China a free, prosperous, and powerful nation...

: "nationalism, democracy, and people's livelihood".

The principle of nationalism called for overthrowing the Manchus and ending foreign hegemony over China. The second principle, democracy, was used to describe Sun's goal of a popularly elected republican form of government. People's livelihood, often referred to as socialism, was aimed at helping the common people through regulation of the ownership of the means of production and land.

Hubei

' Hupeh) is a province in Central China. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Lake Dongting...

Province, among discontented modernized army units whose anti-Qing plot had been uncovered. This would be known as the Wuchang Uprising

Wuchang Uprising

The Wuchang Uprising began with the dissatisfaction of the handling of a railway crisis. The crisis then escalated to an uprising where the revolutionaries went up against Qing government officials. The uprising was then assisted by the New Army in a coup against their own authorities in the city...

which is celebrated as Double Tenth Day in Taiwan. It had been preceded by numerous abortive uprisings and organized protests inside China. The revolt quickly spread to neighboring cities, and Tongmenghui members throughout the country rose in immediate support of the Wuchang revolutionary forces. On October 12, the Revolutionaries succeeded in capturing Hankou

Hankou

Hankou was one of the three cities whose merging formed modern-day Wuhan, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers where the Han falls into the Yangtze...

and Hanyang

Hanyang

Hanyang was one of the three cities that merged into modern-day Wuhan, the capital of the Hubei province, People's Republic of China. Currently, it is a district and stands between the Han River and the Yangtze River, where the former falls into the latter...

.

However this euphoria over the revolution was short-lived. On October 27, Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai was an important Chinese general and politician famous for his influence during the late Qing Dynasty, his role in the events leading up to the abdication of the last Qing Emperor of China, his autocratic rule as the second President of the Republic of China , and his short-lived...

was appointed by the Qing Court to lead his New Armies, including the First Army led by Feng Guozhang

Feng Guozhang

Féng Guózhāng, was a key Beiyang Army general and politician in early republican China. He held the office of Vice-President and then President of the Republic of China...

and the Second Army led by Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui was a Chinese warlord and politician, commander in the Beiyang Army, and the Provisional Chief Executive of Republic of China from November 24, 1924 to April 20, 1926. He was arguably the most powerful man in China from 1916 to 1920.- Early life :Born in Hefei as Duan Qirui , his...

, to retake the city of Wuhan

Wuhan

Wuhan is the capital of Hubei province, People's Republic of China, and is the most populous city in Central China. It lies at the east of the Jianghan Plain, and the intersection of the middle reaches of the Yangtze and Han rivers...

, which was taken by the Revolutionary Army on October 11. The Revolutionary Army had some six thousand troops to fend off nearly fifteen thousand of Yuan's New Army. On November 11, the Revolutionaries retreated from Wuhan to Hanyang.

By November 27, Hanyang was also lost and the Revolutionaries had to return to their starting point, Wuchang. However, during some fifty days of warfare against Yuan's army, fifteen of the twenty-four provinces had declared their independence of the Qing empire. A month later, Sun Yat-sen returned to China from the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, where he had been raising funds among overseas Chinese and American sympathizers. On January 1, 1912, delegates from the independent provinces elected Sun Yat-sen as the first Provisional President of the Republic of China.

Because of the short period and fervor in which the provinces declared independence from the Qing Court, Yuan Shikai felt that it was in his best interest to negotiate with the Revolutionaries. Yuan agreed to accept the Republic of China, and as such most of the rest of the New Armies were now turned against the Qing Dynasty. The chain of events forced the last emperor of China, Puyi

Puyi

Puyi , of the Manchu Aisin Gioro clan, was the last Emperor of China, and the twelfth and final ruler of the Qing Dynasty. He ruled as the Xuantong Emperor from 1908 until his abdication on 12 February 1912. From 1 to 12 July 1917 he was briefly restored to the throne as a nominal emperor by the...

, to abdicate, on February 12 upon Yuan Shikai's suggestion to Empress Dowager Longyu

Empress Dowager Longyu

Empress Xiao Ding Jing ; is better known as the Empress Dowager Longyu , . Also , she had the nickname was Xizi (喜子). Empress Xiao Ding Jing was the Qing Dynasty Empress Consort of the Guangxu Emperor who ruled China from 1875 till 1908...

, who signed the abdication papers. Puyi was allowed to continue living in the Forbidden City, however. The Republic of China officially succeeded the Qing Dynasty.

Early Republic

On January 1, 1912, Sun officially declared the establishment of the Republic of China and was inaugurated in NanjingNanjing

' is the capital of Jiangsu province in China and has a prominent place in Chinese history and culture, having been the capital of China on several occasions...

as the first Provisional President

President of the Republic of China

The President of the Republic of China is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the Republic of China . The Republic of China was founded on January 1, 1912, to govern all of China...

. But power in Beijing

Beijing

Beijing , also known as Peking , is the capital of the People's Republic of China and one of the most populous cities in the world, with a population of 19,612,368 as of 2010. The city is the country's political, cultural, and educational center, and home to the headquarters for most of China's...

already had passed to Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai was an important Chinese general and politician famous for his influence during the late Qing Dynasty, his role in the events leading up to the abdication of the last Qing Emperor of China, his autocratic rule as the second President of the Republic of China , and his short-lived...

, who had effective control of the Beiyang Army

Beiyang Army

The Beiyang Army was a powerful, Western-style Chinese military force created by the Qing Dynasty government in the late 19th century. It was the centerpiece of a general reconstruction of China's military system. The Beiyang Army played a major role in Chinese politics for at least three decades...

, the most powerful military force in China at the time. To prevent civil war

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

and possible foreign intervention from undermining the infant republic, Sun agreed to Yuan's demand that China be united under a Beijing government headed by Yuan. On March 10, in Beijing, Yuan Shikai was sworn in as the second Provisional President of the Republic of China.

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang of China , sometimes romanized as Guomindang via the Pinyin transcription system or GMD for short, and translated as the Chinese Nationalist Party is a founding and ruling political party of the Republic of China . Its guiding ideology is the Three Principles of the People, espoused...

(Nationalist Party) was founded by Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren was a Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuomintang . He was assassinated in 1913 after leading his Kuomintang party to victory in China's first democratic elections...

, one of Sun's associates. It was an amalgamation of small political groups, including Sun's Tongmenghui. In the national elections held in February 1913 for the new bicameral parliament, Song campaigned against the Yuan administration, whose representation at the time was largely by the Republican Party, led by Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao |Styled]] Zhuoru, ; Pseudonym: Rengong) was a Chinese scholar, journalist, philosopher and reformist during the Qing Dynasty , who inspired Chinese scholars with his writings and reform movements...

. Song was an able campaigner and the Kuomintang won a majority of seats.

Second Revolution

Some people believe that Yuan Shikai had Song assassinated in March; it has never been proven, although he had already arranged the assassination of several pro-revolutionist generals. Animosity towards Yuan grew. In April, Yuan secured the Reorganization Loan of twenty-five million pounds sterling from Great Britain, France, Russia, Germany and Japan, without consulting the parliament first. The loan was used to finance Yuan's Beiyang Army.On May 20, Yuan concluded a deal with Russia that recognized special Russian privilege in Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was a territory of the Qing Dynasty = the Manchu Empire. Its area was roughly equivalent to that of the modern state of Mongolia, which is sometimes informally called "Outer Mongolia" today...

and restricted Chinese right to station troops there. Kuomintang members of the Parliament accused Yuan of abusing his rights and called for his removal. On the other hand, the Progressive Party

Progressive Party (China)

- Origins :Chinese constitutionalism was a movement that originated after the First Sino-Japanese War . A young group of intellectuals in China led by Kang Youwei argued that China's defeat was due to its lack of modern institutions and legal framework which the Self-Strengthening Movement had...

, which was composed of constitutional monarchists and supported Yuan, accused the Kuomintang of fomenting an insurrection. Yuan then decided to use military action against the Kuomintang.

In July 1913, seven southern provinces rebelled against Yuan, thus beginning the Second Revolution . There were several underlying reasons for the Second Revolution besides Yuan's abuse of power. First was that many Revolutionary Armies from different provinces were disbanded after the establishment of the Republic of China, and many officers and soldiers felt that they were not compensated for toppling the Qing Dynasty. Thus, there was much discontent against the new government among the military. Secondly, many revolutionaries felt that Yuan Shikai and Li Yuanhong were undeserving of the posts of presidency and vice presidency, because they acquired the posts through political maneuvers, rather than participation in the revolutionary movement. And lastly, Yuan's use of violence (such as Song's assassination), dashed Kuomintang's hope of achieving reforms and political goals through electoral means.

However, the Second Revolution did not fare well for the Kuomintang. The leading Kuomintang military force of Jiangxi

Jiangxi

' is a southern province in the People's Republic of China. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze River in the north into hillier areas in the south, it shares a border with Anhui to the north, Zhejiang to the northeast, Fujian to the east, Guangdong to the south, Hunan to the west, and Hubei to...

was defeated by Yuan's forces on August 1 and Nanchang

Nanchang

Nanchang is the capital of Jiangxi Province in southeastern China. It is located in the north-central portion of the province. As it is bounded on the west by the Jiuling Mountains, and on the east by Poyang Lake, it is famous for its scenery, rich history and cultural sites...

was taken. On September 1, Nanjing was taken. When the rebellion was suppressed, Sun and other instigators fled to Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

. In October 1913 an intimidated parliament formally elected Yuan Shikai President of the Republic of China

President of the Republic of China

The President of the Republic of China is the head of state and commander-in-chief of the Republic of China . The Republic of China was founded on January 1, 1912, to govern all of China...

, and the major powers extended recognition to his government. Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui was a Chinese warlord and politician, commander in the Beiyang Army, and the Provisional Chief Executive of Republic of China from November 24, 1924 to April 20, 1926. He was arguably the most powerful man in China from 1916 to 1920.- Early life :Born in Hefei as Duan Qirui , his...

and other trusted Beiyang generals were given prominent positions in cabinet. To achieve international recognition, Yuan Shikai had to agree to autonomy for Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was a territory of the Qing Dynasty = the Manchu Empire. Its area was roughly equivalent to that of the modern state of Mongolia, which is sometimes informally called "Outer Mongolia" today...

and Tibet

Tibet

Tibet is a plateau region in Asia, north-east of the Himalayas. It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people as well as some other ethnic groups such as Monpas, Qiang, and Lhobas, and is now also inhabited by considerable numbers of Han and Hui people...

. China was still to be suzerain, but it would have to allow Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

a free hand in Outer Mongolia and Tanna Tuva

Tuva

The Tyva Republic , or Tuva , is a federal subject of Russia . It lies in the geographical center of Asia, in southern Siberia. The republic borders with the Altai Republic, the Republic of Khakassia, Krasnoyarsk Krai, Irkutsk Oblast, and the Republic of Buryatia in Russia and with Mongolia to the...

and Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

continuation of its influence in Tibet.

Mass Banditry, Yuan Shikai, and the National Protection War

Mass bandit leaders with popular movements like the Bai Lang Rebellion

Bai Lang Rebellion

The Bai Lang Rebellion, was a Chinese "bandit" rebellion that lasted from mid-1913 to late-1914. Launched against the Republican government of Yuan Shikai, the rebellion was led by Bai Lang...

broke out, with the support of Sun Yatsen's revolutionaries from Canton, the Bandit leader Bai Lang ransacked and destroyed much of central China before he was crushed by the Beiyang Army

Beiyang Army

The Beiyang Army was a powerful, Western-style Chinese military force created by the Qing Dynasty government in the late 19th century. It was the centerpiece of a general reconstruction of China's military system. The Beiyang Army played a major role in Chinese politics for at least three decades...

of Yuan Shikai, the Muslim Ma Clique

Ma clique

The Ma clique or Ma family warlords is a collective name for a group of Muslim warlords in Northwestern China who ruled the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Ningxia from the 1910s until 1949. There were 3 families in the Ma clique , each of them respectively controlled 3 areas, Gansu,...

and Tibetan militia. These bandits were associated with the Gelaohui

Gelaohui

The Gelaohui , also called Futaubang, or Hatchet Gang , as every member allegedly carried a small hatchet inside the sleeve, was a secret society and underground resistance movement associated with the revolutionary Tongmenghui led by Sun Yat-sen and Song Jiaoren.Originating in western china,...

.

In November Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai was an important Chinese general and politician famous for his influence during the late Qing Dynasty, his role in the events leading up to the abdication of the last Qing Emperor of China, his autocratic rule as the second President of the Republic of China , and his short-lived...

, legally president, ordered the Kuomintang dissolved and forcefully removed its members from parliament. Because the majority of the parliament members belonged to the Kuomintang, the parliament did not meet quorum

Quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly necessary to conduct the business of that group...

and was subsequently unable to convene. In January 1914 Yuan formally suspended the parliament. In February, Yuan called into session a meeting to revise the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China, which was announced in May of that year. The revision greatly expanded Yuan's powers, allowing him to declare war, sign treaties, and appoint officials without seeking approvals from the legislature first. In December 1914, he further revised the law and lengthened the term of the President to ten years, with no term limit. Essentially Yuan was preparing for his ascendancy as the emperor.

On the other hand, since the failure of the Second Revolution, Sun Yat-sen and his allies were trying to rebuild the revolutionary movement. In July 1914, Sun established the Chinese Revolutionary Party

Chinese Revolutionary Party

The Chinese Revolutionary Party was the short lived renaming of the Kuomintang between 1914 and 1919....

. Sun felt that his failures at building a consistent revolutionary movement stemmed from the lack of cohesiveness among its members. Thus, for his new party, Sun required its members to be totally loyal to Sun and follow a series of rather harsh rules. Some of Sun's earlier associates, including Huang Xing, balked at the idea of such authoritarian organization and refused to join Sun. However, they agreed that the republic must not revert back to imperial rule.

Besides the revolutionary groups associated with Sun, there were also several other groups aimed at toppling Yuan Shikai. One was the Progressive Party, the originally constitutional-monarchist party which opposed the Kuomintang during the Second Revolution. The Progressive Party switched their position largely because of Yuan's sabotage of the national parliament. Secondly, many provincial governors, who had declared their independence from the Qing Imperial Court in 1912, found the idea of supporting another Imperial Court utterly ridiculous. Yuan also alienated his Beiyang generals by centralizing tax collection from local authorities. In addition, public opinion was overwhelmingly anti-Yuan.

When World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

broke out in 1914, Japan fought on the Allied side and seized German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

holdings in Shandong

Shandong

' is a Province located on the eastern coast of the People's Republic of China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history from the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River and served as a pivotal cultural and religious site for Taoism, Chinese...

Province. In 1915 the Japanese set before the government in Beijing the so-called Twenty-One Demands

Twenty-One Demands

The ' were a set of demands made by the Empire of Japan under Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu sent to the nominal government of the Republic of China on January 18, 1915, resulting in two treaties with Japan on May 25, 1915.- Background :...

. The Demands aimed to install Japanese economic controls in railway and mining operations in Shandong, Manchuria, Fujian, and pressed to have Yuan Shikai appoint Japanese advisors in key positions in the Chinese government. The Twenty-One Demands would have made China a Japanese protectorate. The Beijing government rejected some of these demands but yielded to the Japanese insistence on keeping the Shandong territory already in its possession. Beijing also recognized Tokyo's authority over southern Manchuria

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

and eastern Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in the northern region of the country. Inner Mongolia shares an international border with the countries of Mongolia and the Russian Federation...

. Yuan's acceptance of the demands was extremely unpopular, but he continued his monarchist agenda nevertheless.

On 12 December 1915, Yuan, supported by his son Yuan Keding

Yuan Keding

Yuán Kèdìng , courtesy name Yuntai was the eldest son of Yuan Shikai. His mother was Yuan's original wife, Yu , and Yuan Kewen was his younger brother....

, declared himself emperor

Self-proclaimed monarchy

A self-proclaimed monarchy is a monarchy that is proclaimed into existence, often by an individual, rather than occurring as part of a longstanding tradition...

of a new Empire of China

Empire of China (1915-1916)

The Empire of China was a short-lived attempt by statesman and general Yuan Shikai from late 1915 to early 1916 to reinstate monarchy in China. The attempt was ultimately a failure, but it set back the Chinese republican cause by many years and fractured China into a hodgepodge of squabbling...

. This sent shockwaves throughout China, causing widespread rebellion in numerous provinces. On 25 December, former Yunnan governor Cai E

Cai E

Cai E or Tsai Ao was a Chinese revolutionary leader and warlord. He was born Cai Genyin in Shaoyang, Hunan, and his courtesy name was Songpo...

, former Jiangxi governor Li Liejun

Li Liejun

Li Liejun, 李烈钧, was a Chinese revolutionary leader and general.Li was born in Wuning, Jiangxi, China. He went on to get a higher education and was sent to the Imperial Japanese Army Academy where he joined the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance...

, and Yunnan general Tang Jiyao

Tang Jiyao

Tang Jiyao was a Chinese general and warlord of Yunnan during the Warlord Era of Republican China. Tang Jiyao was military governor of Yunnan from 1913-1927.-Life:...

formed the National Protection Army and declared Yunnan independent. Thus began the National Protection War

National Protection War

The National Protection War , also known as the anti-Monarchy War, was a civil war that took place in China between 1915 and 1916. The cause of this war was Yuan Shikai's proclamation of himself as Emperor. Only three years earlier, the last Chinese dynasty, the Qing Dynasty, had been overthrown...

.

Yunnan's declaration of independence also encouraged other southern provinces to declare independence. Yuan's Beiyang generals, who were already wary of Yuan's imperial coronation, did not put up an aggressive campaign against the National Protection Army. On 22 March 1916, Yuan formally repudiated monarchy and stepped down as the first and last emperor of his dynasty. Yuan died on 6 June of that year. Vice President Li Yuanhong

Li Yuanhong

Li Yuanhong was a Chinese general and political figure during the Qing dynasty and the republican era. He was twice president of the Republic of China.- Early history :...

assumed presidency and appointed Beiyang general Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui was a Chinese warlord and politician, commander in the Beiyang Army, and the Provisional Chief Executive of Republic of China from November 24, 1924 to April 20, 1926. He was arguably the most powerful man in China from 1916 to 1920.- Early life :Born in Hefei as Duan Qirui , his...

as his Premier. Yuan Shikai's imperial ambitions finally ended with the return of republican government.

Warlord Era (1916-1928)

After Yuan Shikai's death, shifting alliances of regional warlords fought for control of the Beijing government. Despite the fact that various warlords gained control of the government in Beijing during the warlord era, this did not constitute a new era of control or governance, because other warlords did not acknowledge the transitory governments in this period and were a law unto themselves. These military-dominated governments were collectively known as the Beiyang governmentBeiyang Government

The Beiyang government or warlord government collectively refers to a series of military regimes that ruled from Beijing from 1912 to 1928 at Zhongnanhai. It was internationally recognized as the legitimate Government of the Republic of China. The name comes from the Beiyang Army which dominated...

. The warlord era is considered by some historians to have ended in 1927.

World War I and brief Manchu restoration

After Yuan Shikai's death, Li YuanhongLi Yuanhong

Li Yuanhong was a Chinese general and political figure during the Qing dynasty and the republican era. He was twice president of the Republic of China.- Early history :...

became the President and Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui

Duan Qirui was a Chinese warlord and politician, commander in the Beiyang Army, and the Provisional Chief Executive of Republic of China from November 24, 1924 to April 20, 1926. He was arguably the most powerful man in China from 1916 to 1920.- Early life :Born in Hefei as Duan Qirui , his...

became the Premier. The Provisional Constitution was reinstated and the parliament convened. However, Li Yuanhong and Duan Qirui had many conflicts, the most glaring of which was China's entry into World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. Since the outbreak of the war, China had remained neutral until the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

urged all neutral countries to join the Allies

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

, as a condemnation of Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

's use of unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchantmen without warning, as opposed to attacks per prize rules...

. Premier Duan Qirui was particularly interested in joining the Allies, because he would then use the opportunity to secure loans from Japan to build up his Anhui Clique

Anhui clique

The Anhui clique was one of several mutually hostile cliques or factions that split from the Beiyang Clique in the Republic of China's Warlord era. It was named after Anhui province because several of its generals including its founder, Duan Qirui, was born in Anhui...

army. The two factions in the parliament engaged in ugly debates regarding the entry of China and, in May 1917, Li Yuanhong dismissed Duan Qirui from his government.

Duan's dismissal caused provincial military governors loyal to Duan to declare independence and to call for Li Yuanhong to step down as the President. Li Yuanhong summoned Zhang Xun

Zhang Xun (Republic of China)

Zhang Xun was a Qing-loyalist general who attempted to restore the abdicated emperor Puyi in 1917. He supported Yuan Shikai during his time as president....

to mediate the situation. Zhang Xun had been a general serving the Qing Court and was by this time the military governor of Anhui province. He had his mind on restoring Puyi

Puyi

Puyi , of the Manchu Aisin Gioro clan, was the last Emperor of China, and the twelfth and final ruler of the Qing Dynasty. He ruled as the Xuantong Emperor from 1908 until his abdication on 12 February 1912. From 1 to 12 July 1917 he was briefly restored to the throne as a nominal emperor by the...

(or Xuantong Emperor) to the imperial throne. Zhang was supplied with funds and weapons through the German legation who were eager to keep China neutral.

On July 1, 1917, Zhang officially proclaimed that the Qing Dynasty

Qing Dynasty

The Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

has been restored and requested that Li Yuanhong give up his seat as the President, which Li promptly rejected. During the restoration affair, Duan Qirui led his army and defeated Zhang Xun's restoration forces in Beijing. One of Duan's airplanes bombed the Forbidden City, in what was possibly the first aerial bombardment in East Asia. On July 12 Zhang's forces disintegrated and Duan returned to Beijing.

The Manchu restoration ended almost as soon as it began. During this period of confusion, Vice President Feng Guozhang

Feng Guozhang

Féng Guózhāng, was a key Beiyang Army general and politician in early republican China. He held the office of Vice-President and then President of the Republic of China...

, also a Beiyang general, assumed the post of Acting President of the republic and was sworn-in in Nanjing. Duan Qirui resumed his post as the Premier. The Zhili Clique of Feng Guozhang and the Anhui Clique

Anhui clique

The Anhui clique was one of several mutually hostile cliques or factions that split from the Beiyang Clique in the Republic of China's Warlord era. It was named after Anhui province because several of its generals including its founder, Duan Qirui, was born in Anhui...

of Duan Qirui emerged as the most powerful cliques following the restoration affair.

Duan Qirui's triumphant return to Beijing essentially made him the most powerful leader in China. Duan dissolved the parliament upon his return and declared war on Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

on August 13, 1917. German and Austro-Hungarian nationals were detained and their assets seized. Around 175,000 Chinese workers volunteered for labour battalions

Chinese Labour Corps

The Chinese Labour Corps was a force of workers recruited by the British government in World War I to support the troops by performing support work and manual labor.-History:...

after being enticed with money, some even years before war was declared. They were sent to the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

, German East Africa

German East Africa

German East Africa was a German colony in East Africa, which included what are now :Burundi, :Rwanda and Tanganyika . Its area was , nearly three times the size of Germany today....

, and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

and served on supply ships. Some 10,000 died including over 500 due to U-boats. No soldiers were sent overseas though they did participate with the Allies in the Siberian Intervention

Siberian Intervention

The ', or the Siberian Expedition, of 1918–1922 was the dispatch of troops of the Entente powers to the Russian Maritime Provinces as part of a larger effort by the western powers and Japan to support White Russian forces against the Bolshevik Red Army during the Russian Civil War...

under Japanese General Kikuzo Otani.

Constitutional Protection War

In September, Duan's complete disregard for the constitution caused Sun Yat-sen and the deposed parliament members to establish a new government in GuangzhouGuangzhou

Guangzhou , known historically as Canton or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of the Guangdong province in the People's Republic of China. Located in southern China on the Pearl River, about north-northwest of Hong Kong, Guangzhou is a key national transportation hub and trading port...

and the Constitutional Protection Army to counter Duan's abuse of power. Ironically, Sun Yat-sen's new government was not based on the Provisional Constitution. Rather, the new government was a military government and Sun was its "Grand Commander of the Armed Forces" ' onMouseout='HidePop("58827")' href="/topics/Generalissimo">Generalissimo

Generalissimo

Generalissimo and Generalissimus are military ranks of the highest degree, superior to Field Marshal and other five-star ranks.-Usage:...

"). Six southern provinces became part of Sun's Guangzhou military government and repelled Duan's attempt to destroy the Constitutional Protection Army.

The Constitutional Protection War continued through 1918. Many in Sun Yat-sen's Guangzhou government felt Sun's position as the Generalissimo was too exclusionary and promoted a cabinet system to challenge Sun's ultimate authority. As a result, the Guangzhou government was reorganized to elect a seven-member cabinet system, known as the Governing Committee. Sun was once again sidelined by his political opponents and military strongmen. He left for Shanghai following the reorganization.

Duan Qirui's Beijing government did not fare much better than Sun's. Some generals in Duan's Anhui Clique and others in the Zhili Clique did not want to use force to unify the southern provinces. They felt negotiation was the solution to unify China and forced Duan to resign in October. In addition, many were distressed by Duan's borrowing of huge sums of Japanese money to fund his army to fight internal enemies.

President Feng Guozhang, with his term expiring, was then succeeded by Xu Shichang, who wanted to negotiate with the southern provinces. In February 1919, delegates from the northern and southern provinces convened in Shanghai to discuss postwar situations. However, the meeting broke down over Duan's borrowing of Japanese loans to fund the Anhui Clique army and further attempts at negotiation were hampered by the May Fourth Movement

May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement growing out of student demonstrations in Beijing on May 4, 1919, protesting the Chinese government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, especially the Shandong Problem...

. The Constitutional Protection War essentially left China divided along the north-south border.

May Fourth Movement

May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement growing out of student demonstrations in Beijing on May 4, 1919, protesting the Chinese government's weak response to the Treaty of Versailles, especially the Shandong Problem...

.

The intellectual milieu in which the May Fourth Movement developed was known as the New Culture Movement

New Culture Movement

The New Culture Movement of the mid 1910s and 1920s sprang from the disillusionment with traditional Chinese culture following the failure of the Chinese Republic, founded in 1912 to address China’s problems. Scholars like Chen Duxiu, Cai Yuanpei, Li Dazhao, Lu Xun, Zhou Zuoren, and Hu Shi, had...

and occupied the period from 1917 to 1923. The student demonstrations of May 4, 1919 were the high point of the New Culture Movement, and the terms are often used synonymously. Chinese representatives refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

, due to intense pressure from the student protesters and public opinion alike.

Fight against warlordism and the First United Front

The May Fourth Movement helped to rekindle the then-fading cause of republican revolution. In 1917 Sun Yat-sen had become commander-in-chief of a rival military government in CantonGuangzhou

Guangzhou , known historically as Canton or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of the Guangdong province in the People's Republic of China. Located in southern China on the Pearl River, about north-northwest of Hong Kong, Guangzhou is a key national transportation hub and trading port...

in collaboration with southern warlords. In October 1919, Sun reestablished the Kuomintang

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang of China , sometimes romanized as Guomindang via the Pinyin transcription system or GMD for short, and translated as the Chinese Nationalist Party is a founding and ruling political party of the Republic of China . Its guiding ideology is the Three Principles of the People, espoused...

(KMT) to counter the government in Beijing. The latter, under a succession of warlords, still maintained its facade of legitimacy and its relations with the West.

By 1921, Sun had become president of the southern government. He spent his remaining years trying to consolidate his regime and achieve unity with the north. His efforts to obtain aid from the Western democracies were ignored, however, and in 1920 he turned to the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, which had recently achieved its own revolution. The Soviets sought to befriend the Chinese revolutionists by offering scathing attacks on Western imperialism. But for political expediency, the Soviet leadership initiated a dual policy of support for both Sun and the newly established Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

In 1922 the Kuomintang-warlord alliance in Guangzhou was ruptured, and Sun fled to Shanghai

Shanghai

Shanghai is the largest city by population in China and the largest city proper in the world. It is one of the four province-level municipalities in the People's Republic of China, with a total population of over 23 million as of 2010...

. By then, Sun saw the need to seek Soviet support for his cause. In 1923, a joint statement by Sun and a Soviet representative in Shanghai pledged Soviet assistance for China's national unification. Soviet advisers — the most prominent of whom was an agent of the Comintern

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern, also known as the Third International, was an international communist organization initiated in Moscow during March 1919...

, Mikhail Borodin

Mikhail Borodin

Mikhail Markovich Borodin was the alias of Mikhail Gruzenberg, a Comintern agent and Soviet arms dealer....

— began to arrive in China in 1923 to aid in the reorganization and consolidation of the Kuomintang along the lines of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

and establish the First United Front. The CCP was under Comintern instructions to cooperate with the Kuomintang, and its members were encouraged to join while maintaining their party identities to form a "bloc within."

The policy of working with the Kuomintang and Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek was a political and military leader of 20th century China. He is known as Jiǎng Jièshí or Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng in Mandarin....

had been recommended by the Dutch Communist Henk Sneevliet

Henk Sneevliet

Hendricus Josephus Franciscus Marie Sneevliet, known as Henk Sneevliet or the pseudonym Maring , was a Dutch Communist, who was active in both the Netherlands and the Dutch East-Indies...

, chosen in 1923 to be the Comintern representative in China due to his revolutionary experience in the Dutch Indies, where he had a major role in founding the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI) - and who felt that the Chinese party was too small and weak to undertake a major effort on its own.

The CCP was still small at the time, having a membership of 300 in 1921 and only 1,500 by 1925. The Kuomintang in 1922 already had 150,000 members. Soviet advisers also helped the Kuomintang set up a political institute to train propagandists in mass mobilization techniques and in 1923 sent Chiang Kai-shek, one of Sun's lieutenants from Tongmenghui days, for several months' military and political study in Moscow. After Chiang's return in late 1923, he participated in the establishment of the Whampoa Military Academy

Whampoa Military Academy

The Nationalist Party of China Army Officer Academy , commonly known as the Whampoa Military Academy , was a military academy in the Republic of China that produced many prestigious commanders who fought in many of China's conflicts in the 20th century, notably the Northern Expedition, the Second...

outside Guangzhou, which was the seat of government under the Kuomintang-CCP alliance. In 1924 Chiang became head of the academy and began the rise to prominence that would make him Sun's successor as head of the Kuomintang and the unifier of all China under the right-wing nationalist government.

Chiang consolidates power

Beijing

Beijing , also known as Peking , is the capital of the People's Republic of China and one of the most populous cities in the world, with a population of 19,612,368 as of 2010. The city is the country's political, cultural, and educational center, and home to the headquarters for most of China's...

in March 1925, as the Nationalist movement he had helped to initiate was gaining momentum. During the summer of 1925, Chiang, as commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army

National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army , pre-1928 sometimes shortened to 革命軍 or Revolutionary Army and between 1928-1947 as 國軍 or National Army was the Military Arm of the Kuomintang from 1925 until 1947, as well as the national army of the Republic of China during the KMT's period of party rule...

, set out on the long-delayed Northern Expedition against the northern warlords. Within nine months, half of China had been conquered. By 1926, however, the Kuomintang had divided into left- and right-wing factions, and the Communist bloc within it was also growing.

In March 1926, after thwarting a kidnapping attempt against him (Zhongshan Warship Incident

Zhongshan Warship Incident

The Zhongshan Warship Incident , or "March 20th Incident", on March 20, 1926, involved a suspected plot by Captain Li Zhilong of the warship Chung Shan to kidnap Chiang Kai-shek. It triggered a political struggle between the Communist Party of China and Kuomintang...

), Chiang abruptly dismissed his Soviet advisers, imposed restrictions on CCP members' participation in the top leadership, and emerged as the preeminent Kuomintang leader. The Soviet Union, still hoping to prevent a split between Chiang and the CCP, ordered Communist underground activities to facilitate the Northern Expedition, which was finally launched by Chiang from Guangzhou in July 1926.

In early 1927, the Kuomintang-CCP rivalry led to a split in the revolutionary ranks. The CCP and the left wing of the Kuomintang had decided to move the seat of the Nationalist government from Guangzhou to Wuhan

Wuhan

Wuhan is the capital of Hubei province, People's Republic of China, and is the most populous city in Central China. It lies at the east of the Jianghan Plain, and the intersection of the middle reaches of the Yangtze and Han rivers...

. But Chiang, whose Northern Expedition was proving successful, set his forces to destroying the Shanghai CCP apparatus and established an anti-Communist government at Nanjing in April 1927 - bloody events

April 12 Incident

The April 12 Incident of 1927 refers to the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party organizations in Shanghai by the military forces of Chiang Kai-shek and conservative factions in the Kuomintang...

. There now were three capitals in China: the internationally recognized warlord regime in Beijing; the Communist and left-wing Kuomintang regime at Wuhan; and the right-wing civilian-military regime at Nanjing, which would remain the Kuomintang capital for the next decade.

The Comintern cause appeared bankrupt. A new policy was instituted calling on the CCP to foment armed insurrections in both urban and rural areas in preparation for an expected rising tide of revolution. Unsuccessful attempts were made by Communists to take cities such as Nanchang

Nanchang

Nanchang is the capital of Jiangxi Province in southeastern China. It is located in the north-central portion of the province. As it is bounded on the west by the Jiuling Mountains, and on the east by Poyang Lake, it is famous for its scenery, rich history and cultural sites...

, Changsha, Shantou

Shantou

Shantou , historically known as Swatow or Suátao, is a prefecture-level city on the eastern coast of Guangdong province, People's Republic of China, with a total population of 5,391,028 as of 2010 and an administrative area of...

, and Guangzhou, and an armed rural insurrection, known as the Autumn Harvest Uprising

Autumn Harvest Uprising

The Autumn Harvest Uprising was an insurrection that took place in Hunan province and Jiangxi province, China on September 7, 1927, led by Mao Zedong, who established a short-lived Hunan Soviet....

, was staged by peasants in Hunan

Hunan

' is a province of South-Central China, located to the south of the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and south of Lake Dongting...

Province. The insurrection was led by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

, who would later become chairman of the CCP and head of state of the People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China

China , officially the People's Republic of China , is the most populous country in the world, with over 1.3 billion citizens. Located in East Asia, the country covers approximately 9.6 million square kilometres...

.

But in mid-1927, the CCP was at a low ebb. The Communists had been expelled from Wuhan by their left-wing Kuomintang allies, who in turn were toppled by a military regime. By 1928, all of China was at least nominally under Chiang's control, and the Nanjing government received prompt international recognition as the sole legitimate government of China. The Kuomintang government announced that in conformity with Sun Yat-sen's formula for the three stages of revolution — military unification, political tutelage, and constitutional democracy — China had reached the end of the first phase and would embark on the second, which would be under Kuomintang direction.

Nanjing Decade (1928-1937)

Democracy in China

Democracy was a major concept introduced to China in the late nineteenth century. The debate over its form and definition as well as application was one of the major ideological battlegrounds in Chinese politics for well over a century. It is still a contentious subject...

, and cultural creativity. Some of the harsh aspects of foreign concessions and privileges in China were moderated through diplomacy. In May 1930 the government regained the right to set its tariff

Tariff

A tariff may be either tax on imports or exports , or a list or schedule of prices for such things as rail service, bus routes, and electrical usage ....

, which before then had been set by the foreign powers.

The Nationalist government acted also energetically to modernize the legal and penal systems, stabilize prices, amortize debts, reform the banking and currency systems, build railroads and highways, improve public health facilities, legislate against traffic in narcotics, and augment industrial and agricultural production. On November 3, 1935 the government instituted the fiat currency (fapi) reform, immediately stabilizing prices and also raising revenues for the government. Great strides also were made in education and, in an effort to help unify Chinese society, in a program to popularize Modern Standard Chinese and overcome other varieties of Chinese

Varieties of Chinese

Chinese comprises many regional language varieties sometimes grouped together as the Chinese dialects, the primary ones being Mandarin, Wu, Cantonese, and Min. These are not mutually intelligible, and even many of the regional varieties are themselves composed of a number of...

. Newspapers, magazines, and book publishing flourished, and the widespread establishment of communications facilities further encouraged a sense of unity and pride among the people.

Laws were passed and campaigns mounted to promote the rights of women, The ease and speed of communication also allowed a focus on social problems, including those of the villages. The Rural Reconstruction Movement

Rural Reconstruction Movement

The Rural Reconstruction Movement was started in China in the 1920s by Y.C. James Yen, Liang Shuming and others to revive the Chinese village. They strove for a middle way, independent of the Nationalist government but in competition with the radical revolutionary approach to the village espoused...

was one of many which took advantage of the new freedom to raise social consciousness. On the other hand, political freedom was considerably curtailed because of the Kuomintang's one-party domination through "political tutelage" and often violent means in shutting down anti-government protests.

During this time a series of massive wars took place in western China, the Kumul Rebellion

Kumul Rebellion

The Kumul Rebellion was a rebellion of Kumulik Uyghurs who conspired with the Chinese Muslim General Ma Zhongying to overthrow Jin Shuren, governor of Xinjiang. The Kuomintang wanted Jin removed because of his ties to the Soviet Union, so it approved of the operation while pretending to acknowledge...

, Sino-Tibetan War

Sino-Tibetan War

The Sino–Tibetan War occurred in 1930–1932 when the Tibetan army under the 13th Dalai Lama invaded Xikang and Yushu in Qinghai in a dispute over monasteries. The Ma clique warlord Ma Bufang secretly sent a telegram to the Sichuan warlord Liu Wenhui, and the leader of the Republic of China, Chiang...

, Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang

Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang

The Soviet invasion of Xinjiang was a military campaign in the Chinese northwestern region of Xinjiang in 1934. White Russian forces assisted the Soviet Red Army.- Background :...

, and Xinjiang War (1897).

Although the central government was nominally in control of the entire country during this period, large areas of China remained under the semi-autonomous rule of local warlords, provincial military leaders, or warlord coalitions. Nationalist rule was strongest in the eastern regions of China around the capital Nanjing, but regional militarists such as Feng Yuxiang

Feng Yuxiang

Feng Yuxiang was a warlord and leader in Republican China. He was also known as the Christian General for his zeal to convert his troops and the Betrayal General for his penchant to break with the establishment. In 1911, he was an officer in the ranks of Yuan Shikai's Beiyang Army but joined...

and Yan Xishan

Yan Xishan

Yan Xishan, was a Chinese warlord who served in the government of the Republic of China. Yan effectively controlled the province of Shanxi from the 1911 Xinhai Revolution to the 1949 Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War...

retained considerable local authority. The Central Plains War

Central Plains War

Central Plains War was a civil war within the factionalised Kuomintang that broke out in 1930. It was fought between the forces of Chiang Kai-shek and the coalition of three military commanders who had previously allied with Chiang: Yan Xishan, Feng Yuxiang, and Li Zongren...

in 1930, the Japanese aggression in 1931, and the Red Army's Long March

Long March

The Long March was a massive military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Communist Party of China, the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the Kuomintang army. There was not one Long March, but a series of marches, as various Communist armies in the south...

led to more power for the central government, but there continued to be foot dragging and even outright defiance, as in the Fujian Rebellion

Fujian People's Government

The People's Revolutionary Government of the Republic of China , also known as the Fujian People's Government , was a short-lived anti-Kuomintang government in the Republic of China's Fujian Province...

of 1933-34.

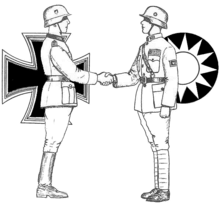

Second Sino-Japanese War (1936-1945)

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese designs on China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

. Hungry for raw materials and pressed by a growing population, Japan initiated the seizure of Manchuria

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

in September 1931 and established ex-Qing emperor Puyi

Puyi

Puyi , of the Manchu Aisin Gioro clan, was the last Emperor of China, and the twelfth and final ruler of the Qing Dynasty. He ruled as the Xuantong Emperor from 1908 until his abdication on 12 February 1912. From 1 to 12 July 1917 he was briefly restored to the throne as a nominal emperor by the...

as head of the puppet state

Puppet state

A puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

of Manchukuo

Manchukuo

Manchukuo or Manshū-koku was a puppet state in Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia, governed under a form of constitutional monarchy. The region was the historical homeland of the Manchus, who founded the Qing Empire in China...

in 1932. The loss of Manchuria, and its vast potential for industrial development and war industries, was a blow to the Kuomintang economy. The League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, established at the end of World War I, was unable to act in the face of the Japanese defiance.

The Japanese began to push from south of the Great Wall

Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China is a series of stone and earthen fortifications in northern China, built originally to protect the northern borders of the Chinese Empire against intrusions by various nomadic groups...

into northern China and into the coastal provinces. Chinese fury against Japan was predictable, but anger was also directed against Chiang and the Nanking government, which at the time was more preoccupied with anti-Communist extermination campaigns than with resisting the Japanese invaders. The importance of "internal unity before external danger" was forcefully brought home in December 1936, when Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek was a political and military leader of 20th century China. He is known as Jiǎng Jièshí or Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng in Mandarin....

, in an event now known as the Xi'an Incident

Xi'an Incident

The Xi'an Incident of December 1936 is an important episode of Chinese modern history, taking place in the city of Xi'an during the Chinese Civil War between the ruling Kuomintang and the rebel Chinese Communist Party and just before the Second Sino-Japanese War...

was kidnapped by Zhang Xueliang

Zhang Xueliang

Zhang Xueliang or Chang Hsüeh-liang , occasionally called Peter Hsueh Liang Chang in English, nicknamed the Young Marshal , was the effective ruler of Manchuria and much of North China after the assassination of his father, Zhang Zuolin, by the Japanese on 4 June 1928...

and forced to ally with the Communists against the Japanese in the Second Kuomintang-CCP United Front

Second United Front (China)

The Second United Front was the alliance between the Kuomintang and Communist Party of China during the Second Sino-Japanese War or World War II, which suspended the Chinese Civil War from 1937 to 1946....

against Japan.

Shanghai

Shanghai is the largest city by population in China and the largest city proper in the world. It is one of the four province-level municipalities in the People's Republic of China, with a total population of over 23 million as of 2010...

fell after a three month battle

Battle of Shanghai

The Battle of Shanghai, known in Chinese as Battle of Songhu, was the first of the twenty-two major engagements fought between the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China and the Imperial Japanese Army of the Empire of Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War...

which ended after severe Japanese naval and army casualties. The capital of Nanjing

Nanjing

' is the capital of Jiangsu province in China and has a prominent place in Chinese history and culture, having been the capital of China on several occasions...

fell in December 1937. It was followed by a series of mass killings and rape of civilians in the Nanjing Massacre. The national capital was briefly at Wuhan

Wuhan

Wuhan is the capital of Hubei province, People's Republic of China, and is the most populous city in Central China. It lies at the east of the Jianghan Plain, and the intersection of the middle reaches of the Yangtze and Han rivers...

, then removed in an epic retreat to Chongqing

Chongqing

Chongqing is a major city in Southwest China and one of the five national central cities of China. Administratively, it is one of the PRC's four direct-controlled municipalities , and the only such municipality in inland China.The municipality was created on 14 March 1997, succeeding the...

, the seat of government until 1945. In 1940 the collaborationist

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

Wang Jingwei regime was set up with its capital in Nanjing, proclaiming itself the legitimate "Republic of China" in opposition to Chiang Kai-shek's government, though its claims were significantly hampered due to its nature as a Japanese puppet state

Puppet state

A puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

controlling limited amounts of territory, along with its subsequent defeat at the end of the war.

The United Front between the Kuomintang and CCP took place with salutary effects for the beleaguered CCP, despite Japan's steady territorial gains in northern China, the coastal regions, and the rich Yangtze River

Yangtze River

The Yangtze, Yangzi or Cháng Jiāng is the longest river in Asia, and the third-longest in the world. It flows for from the glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau in Qinghai eastward across southwest, central and eastern China before emptying into the East China Sea at Shanghai. It is also one of the...

Valley in central China. After 1940, conflicts between the Kuomintang and Communists became more frequent in the areas not under Japanese control

Free China (Second Sino-Japanese War)

The term Free China, in the context of the Second Sino-Japanese War, refers to those areas of China not under the control of the Imperial Japanese Army or any of its puppet governments, such as Manchukuo, the Mengjiang government in Suiyuan and Chahar, or the Provisional Government of the Republic...

. The entrance of the United States into the Pacific War

Pacific War

The Pacific War, also sometimes called the Asia-Pacific War refers broadly to the parts of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, then called the Far East...

after 1941 changed the nature of their relationship. The Communists expanded their influence wherever opportunities presented themselves through mass organizations, administrative reforms, and the land- and tax-reform measures favoring the peasants and the spread of their organizational network, while the Kuomintang attempted to neutralize the spread of Communist influence. Meanwhile northern China was infiltrated politically further more by the Japanese politicians in Manchukuo

Politics of Manchukuo

Manchukuo was a puppet state set up by the Empire of Japan in Manchuria which existed from 1931 to 1945. The Manchukuo regime was established four months after the Japanese withdrawal from Shanghai with Puyi as the nominal but powerless head of state to add some semblance of legitimacy, as he was a...

. Facilities such as Wei Huang Gong is an example.

In 1945, the Republic of China emerged from the war nominally a great military power but actually a nation economically prostrate and on the verge of all-out civil war. The economy deteriorated, sapped by the military demands of foreign war and internal strife, by spiraling inflation, and by Nationalist profiteering, speculation, and hoarding. Starvation came in the wake of the war, and millions were rendered homeless by floods and the unsettled conditions in many parts of the country.

The situation was further complicated by an Allied agreement at the Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

in February 1945 that brought Soviet troops into Manchuria to hasten the termination of war against Japan. Although the Chinese had not been present at Yalta, they had been consulted and had agreed to have the Soviets enter the war in the belief that the Soviet Union would deal only with the Kuomintang government.

After the end of the war in August 1945, the Nationalist government moved back to Nanjing. With American help, Nationalist troops moved to take Japanese surrender in North China. The Soviet Union, as part of the Yalta agreement allowing a Soviet sphere of influence in Manchuria, dismantled and removed more than half the industrial equipment left there by the Japanese. The Soviet presence in northeast China enabled the Communists to move in long enough to arm themselves with the equipment surrendered by the withdrawing Japanese army. The problems of rehabilitating the formerly Japanese-occupied areas and of reconstructing the nation from the ravages of a protracted war were staggering.

See also: Manchukuo

Manchukuo

Manchukuo or Manshū-koku was a puppet state in Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia, governed under a form of constitutional monarchy. The region was the historical homeland of the Manchus, who founded the Qing Empire in China...

, Mengjiang

Mengjiang

Mengjiang , also known in English as Mongol Border Land, was an autonomous area in Inner Mongolia, operating under nominal Chinese sovereignty and Japanese control. It consisted of the then-Chinese provinces of Chahar and Suiyuan, corresponding to the central part of modern Inner Mongolia...

Civil War and transfer of sovereignty over Taiwan (1945-1949)

During World War II, the United States emerged as a major actor in Chinese affairs. As an ally it embarked in late 1941 on a program of massive military and financial aid to the hard-pressed Nationalist government. In January 1943 the United States and Britain led the way in revising their treaties with China, bringing to an end a century of unequal treaty relations. Within a few months, a new agreement was signed between the United States and Republic of China for the stationing of American troops in China for the common war effort against Japan. In December 1943 the Chinese Exclusion Acts of the 1880s and subsequent laws enacted by the United States Congress to restrict Chinese immigration into the United States were repealed.The wartime policy of the United States was initially to help China become a strong ally and a stabilizing force in postwar East Asia

East Asia

East Asia or Eastern Asia is a subregion of Asia that can be defined in either geographical or cultural terms...